Abstract

As a popular process in molecular-based diagnostics, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be employed for amplifying small amounts of DNA/RNA from different sources such as tissue, cells, peripheral blood and so on. Thanks to the unique physicochemical characteristics of nanomaterials and their progress, researchers have been encouraged to employ them as suitable candidates to address the PCR optimization challenges for enhancing efficiency, yield, specificity, and sensitivity. In nanoparticle-assisted PCR (nanoPCR), different nanoparticles (NPs) such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, quantum dots (QDs), and gold (Au) might be used. Among different nanoPCR assays, photothermal PCR has emerged as a technique leveraging the excellent light absorption and heat conversion capabilities of nanomaterials. In addition to presenting recent advances in nanoPCR, this review also delves into the specific use of nanomaterials for photothermal PCR, including their applications in microfluidics as one of the best platforms for miniaturization of diagnostic techniques. Different types of NPs used in PCR are comprehensively examined, and detailed charts and tables are provided that outline features such as optimal concentration and size. The appropriate choice of nanomaterials for enhancing light conversion to heat in PCR applications is discussed. Finally, the related challenges and future trends are explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is utilized as a prevalent strategy to rapidly amplify target nucleic acid structures outside of living organisms. Numerous industries have revealed an extensive range of applications for this technique, such as food safety1, clinical testing2, archaeological examinations3, and biological studies4. There are different inhibitors and facilitators to manipulate PCR performance5. The principal inhibitor in PCR is interference between chemicals and DNA polymerase, nucleic acids (template DNA/primer sequences), or nucleotides (dNTPs)6. The components of human blood such as heme, hemoglobin, lactoferrin, and immunoglobin G7,8,9; hair and skin melanin and eumelanin10,11; organic molecules in soil such as humic and tannic acids12,13; monomeric proteins found in muscle tissue such as myoglobin14; collagen and calcium ions in milk15,16; substances originated from foods such as complex polysaccharides which are presented in feces17,18; and urea found in urine19 are instances of widely used PCR inhibitors. In contrast, the main classifications of PCR facilitators are non-ionic detergents, proteins, organic solvents, extra polymerase enzymes in the presence of enzyme-targeting inhibitors, biological matrices and polymers, PCR cocktails containing more than one additive (e.g., 1,2-propanediol-trehalose (PT) combination), and nanoparticles (NPs) (e.g., carbon nanotubes (CNTs), metal/metal oxides, and quantum dots (QDs)6). NPs are very efficient in facilitating PCR owing to their exceptional characteristics, including their small size, excellent thermal conductivity, high surface-to-volume ratios, and dense surface electric charge20,21. The nanoPCR technique involves the integration of NPs with PCR reagents, which primarily consist of enzymes, templates, and primers. The kinds of nanomaterials utilized in PCR up to now consist of metals (like gold (Au)22 and silver (Ag)23), carbons (like CNTs24, carbon nanopowders (CNPs)25, diamond26, and graphene NPs27), oxides (like zinc oxide (ZnO)28, titanium dioxide (TiO2)29, and graphene oxide (GO)30), and other materials like QDs31.

Photothermal conversion—the action of absorbing photon energy and converting it into thermal energy—is one of the applications of NPs in PCR32. The photoexcited material’s capacity to capture light and its efficiency in converting to heat are two crucial criteria that account for the photothermal conversion efficiency33. As viable candidates for photothermal catalysis, a wide variety of substances have been investigated to date, including metallic nanostructures34,35, semiconductors36,37, carbon-based nanomaterials38,39,40,41, organic polymers42,43, and more recent materials like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)44,45,46,47,48, 2D carbides or nitrates of transition metals (MXenes)49,50,51, and covalent organic frameworks (COFs)52,53,54,55. Considering the diversity in the physicochemical characteristics of nanomaterials, photothermal conversion is improved through three mechanisms: plasmonic localized heating, nonradiative relaxation of excited carriers, and molecular vibrations. Metals exhibit plasmonic localized heating, which increases the radiative scattering and absorption of resonant light when the collective oscillation of the free electrons is driven coherently by the oscillating electric field of light. Semiconductors primarily observe the nonradiative relaxation of excited carriers, which absorbs photon energy surpassing their bandgaps. This process converts energy into heat by facilitating the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conductive band. Next, in the valence band and conduction band, respectively, excitation-state electrons and holes are generated. The electrons and holes in the excitation state then relax to the matching edges of the conductive band and valence band. Thus, the energy is effectively transformed into heat56. The photothermal mechanism through vibrational modes is another technique that occurs in polymer-based and carbon-based nanomaterials57,58,59,60. This mechanism involves light absorption, which excites electrons of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to jump to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO)61, leading some of the excess energy of these excited electrons to be subsequently transferred to the surrounding lattice molecules. This transferred energy induces molecular vibrations, which generate heat. It is important to note that photothermal performance can be significantly improved with well-designed nanomaterials. Nanomaterials can be employed with either a single- or multi-component structure providing photothermal mechanisms.

NanoPCR assays integrated with microfluidics play an essential role in improving the specificity, amplification efficiency, sensitivity, and detection accuracy of diagnostic tests. These techniques, with main advantages such as shortened reaction duration, low reagent utilization, and the capability to manage multiple assays simultaneously on a single disk, are superior to conventional methods. The ability of low-abundance biomarker detection is another benefit of the incorporation of NPs into microfluidics, which enables rapid and early disease detection62,63,64. In this review, we extensively discuss the state-of-the-art nanoPCR processes alongside the implementation of light-to-heat converter NPs in microfluidic devices. Figure 1 shows the frequency of published publications regarding PCR: the red columns represent the number of PCR papers with NPs, the orange columns represent the microfluidic PCR papers’ numbers, and the black columns represent the number of PCR papers with a photothermal effect. The rapid rise of publications on each of the three topics underlines the necessity of this review. In the following sections, we examine nanoPCR assays, and their roles in improving specificity, sensitivity, yield, and efficiency are discussed. The principles of light-to-heat conversion through localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), nonradiative relaxation, and molecular vibrations are presented. In order to understand the basic concepts for the design of photothermal NPs, mathematical principles underlying light-to-heat conversion are presented. We evaluate the photothermal efficiency of different nanostructured materials in biological contexts and highlight recent advancements in photothermal conversion for PCR applications, including the latest developments in on-chip PCR using photothermal nanomaterials.

The annual number of papers published on various topics, including “nanoparticle-based PCR,” “PCR in microfluidics,” and “photothermal PCR,” as determined using Scopus database keywords. The keywords “nanoparticle PCR” and “nanoPCR” are represented in red, “microfluidics-based PCR” and “on-chip PCR” in orange, and “photo PCR,” “photothermal PCR,” “light-to-heat PCR,” and “plasmonic PCR” in black

NanoPCR

Denaturation, annealing, and extension are the three primary stages in each thermal cycle of a PCR reaction (Fig. 2). During the denaturation phase, increasing the temperature up to a high range of 94–98 °C allows the DNA strands to split. During the annealing step, when the temperature is decreased to 50–65 °C, short primers can be attached to the target DNA sequence. Finally, primers offer DNA polymerase a starting point to connect dNTPs and create new complementary DNA strands during the extension process around the temperature of 72 °C. By repeating this process for a certain number of PCR cycles (n times) with a controlled heat cycling speed, the number of DNA strands can be amplified efficiently and precisely. In theory, the exponential function of 2n is commonly expressed to count the number of DNA rises during the PCR process5,65.

Main stages in the PCR process: (1) preparation of double-stranded DNA; (2) denaturation of double-stranded DNA into single-stranded DNA; (3) annealing of short primers to the start and end of the target DNA sequence; and (4) extension of the newly synthesized DNA by attaching dNTPs to the ends of the primers

The detection limit and amplification efficiency of PCR can be affected by the intervention of chemicals in polymerase enzymes or their impact on primers, DNA templates, and dNTPs66. The presence of PCR facilitators during sample preparation can potentially manipulate the PCR performance5. NPs act as one of the best PCR facilitators due to several important mechanisms: they possess excellent thermal conductivity, demonstrate catalytic features, are similar to single-stranded DNA-binding proteins (SSBs), and participate in electrostatic/surface interactions with PCR components67,68. NP-assisted PCR assays with excellent thermal conductivity exhibit improved reaction duration and efficient heat transfer69. The catalytic activity of NPs facilitates the PCR process even under conditions below the optimal environmental standards67. Modifying the negatively charged surface of NPs with carboxyl groups improves the amplification specificity in the PCR process. It minimizes the risk of mispairing between templates and primers by selectively binding to single-stranded DNA in a similar optimization technique to SSBs31. Electrostatic interactions between the positive and negative charges of NPs and PCR components, respectively, play a crucial role in increasing the stability of PCR components and enhancing the efficiency and specificity of PCR70,71,72. In terms of surface interactions, NPs have an impact on PCR in three ways: interaction with polymerase, influencing primers, and template DNA73. Using Au NPs as an illustration (Fig. 3), the adsorption of polymerase by Au NPs regulates the amount of active polymerase in PCR. Au NPs improve PCR specificity by adsorbing primers and increasing the difference in melting temperatures between complementary and mismatched primers. PCR products are adsorbent, and Au NPs assist them to be separated during the denaturing stage68. Understanding the characteristics and properties of the surface of NPs facilitates their selection and optimization for PCR amplification. So far, many NPs have been reported to enhance PCR efficiency and speed up the PCR process, like Au22,74,75, CNT76, Ag77, QD78, GO79, metal oxides (e.g., TiO2, ZnO, and magnesium oxide (MgO))80, and composites. By applying the proper concentration of NPs, they can improve PCR specificity and provide products with enhanced bands. Since low concentrations of NPs inhibit the amplification of long fragments, while high concentrations inhibit the amplification of small fragments and disturb the PCR reaction, it is important to carry out the nanoPCR process with the optimal concentration of NPs73,81. Table 1 lists the effects of NPs of optimal size and concentration that improve the PCR process, and Table 2 illustrates nanoPCR applications in different fields.

Three ways in which Au NPs impact the PCR include: (1) decreasing the PCR’s active polymerase concentration; (2) effectively inhibiting the primer mismatch and formation of nonspecific amplification by decreasing the melting temperatures of the primers; and (3) efficiency improvement and enabling the PCR to run effectively in a faster heat cycler by accelerating the PCR products’ dissociation rate

In Fig. 4, we show the size ranges of different NPs from the literature for PCR applications. Au NPs can be as large as 100 nm, which is over five times the size of other metal NPs utilized in PCR. In terms of size ranges, carbon nanostructures are comparable to metals, with the highest size ranging from 30 nm to 70 nm for CNT/PEI composites and the smallest size of 1 nm for CNTs. To date, the reported optimal sizes for ZnO (35–1000 nm) in the oxide group, PDA (177–328 nm), and ADACP (250–350 nm) in the other composites have been considerably broader than the size ranges for metals and carbons. PEG-nGO and SCM are two other NPs that exhibit optimal sizes of 200 nm and 1000 nm, respectively, which are larger compared to other NPs in the metal and carbon groups.

In Fig. 5, the optimal concentrations of various NPs for PCR applications are shown. It is clear that Au, TiO2, CNT-X (such as MWCNT-Fe3O4, CNT/PEI, and NH2-SWCNTs), and graphene-X (such as GO, GNFs, and GO-Au) with the optimum concentration ranges of 0.19 ⨯ 10−6–0.4 mM, 0.2 ⨯ 10−6–2 mM, 390 ⨯ 10−6-0.63 g/L, and 40 ⨯ 10−6–1 g/L, respectively, are the most commonly used nanomaterials in PCR. The optimal concentrations of other NPs like ZnO nanoflowers (1 mM), CNPs (1 g/L), SWCNTs (1–3 g/L), and MWCNTs (1 g/L) have been observed at high values. CuO, ZnO, Al2O3, Fe3O4, and PDA have been seldom employed for PCR, and the reported optimal concentrations for them are also low.

Light-to-heat conversion mechanisms using NPs

With NPs, one can convert the energy of incoming light into heat energy by releasing the absorbed photon energy into the surrounding environment32. In photothermal conversion, there are three main processes that are very important: the plasmonic effect in metals, the nonradiative energy scattering of excited electron–hole pairs in semiconductors, and molecular vibrations. This section offers a comprehensive analysis of the three principal photothermal processes, as they represent the core principles of photothermal conversion, focusing on the various types of NPs. These NPs are crucial for photothermal conversion, with each category - metallic, semiconducting, and carbon-based exhibiting one or more of these photothermal mechanisms.

Plasmonic localized heating is an optical phenomenon that is mainly associated with the metal NPs, which occurs when the plasmonic resonance on the surface of metallic NPs is subjected to an electromagnetic wave with a wavelength much larger than their size. The incident electric field strongly interacts with the conduction electrons of the metal NPs, leading to their collective oscillation (Fig. 6a (left))82. The absorption of incoming light is further intensified at the resonance frequency, resulting in highly amplified electric fields near the surface of the NPs. This phenomenon is known as LSPR83.

Schematic of the mechanisms involved in photothermal phenomena: (a) schematic illustration of the LSPR effect (left) and localized plasmonic heating by metal nanomaterials (right); (b) localized heating by a non-radiative transition in semiconductors, including Auger recombination (right-top) and Shockley-Read-Hall recombination (right-bottom); (c) localized heating by thermal vibrations

The ability for metal NPs to modify LSPRs across a wide range of the electromagnetic spectrum, from the visible to the infrared, attracted a lot of attention for plasmonic localized heating84,85. The steps involved in achieving localized heating via LSPR are summarized in the schematic of localized plasmonic heating in Fig. 6a (right). (1) Excitation: The stimulation of plasmons has the potential to amplify the electric field intensity at the NP surface, resulting in significant absorption and scattering cross-sections at resonance frequencies. (2) Rapid heating: The nonequilibrium rapid heating of metal NPs occurs when they are activated by resonant photons, leading to the photoexcitation of the electron gas. (3) Relaxation: The electric excitation is followed by relaxation at timescales less than a picosecond, which occurs through electron-electron scattering facilitated by the Landau damping effect. (4) Rapid temperature rise: Electron-electron scattering leads to a fast elevation in the metal’s surface temperature. (5) Heat dissipation in the surrounding media: The surface temperature experiences a fast increase, followed by a cooling process. The cooling process of the lattice occurs through phonon-phonon coupling, leading to the dissipation of heat into the surrounding medium of the NP. The LSPR technique is very fast, as it can produce an extremely concentrated area of surface heat within 100 fs86.

The second way energy is dissipated through processes called non-radiative transitions. These occur when electrons in the excited electronic states in a material decay to lower energy states without the emission of photons. Here, rather than emitting electromagnetic radiation, the energy is radiated out as heat by means of phonon interactions with the nearby atoms or molecules. The materials used in semiconductors are mostly linked to this mechanism87.

Photothermal semiconducting nanomaterials, such as chalcogenides and oxides of metals, governed by this mechanism are also used for heating. These particles are characterized by their bandgap energy, which can be adjusted by manipulating their size, morphology, and surface chemistry88,89,90. By manipulating bandgaps and/or free-carrier-induced LSPRs, the efficiency of light-to-heat transformation conversion in nanomaterials (i.e., semiconductors) can be modulated56,91,92. A rise in local lattice temperature can occur when charge carrier recombination in a semiconductor causes the emission of phonons rather than photons, which produces localized heating as depicted in Fig. 6b schematic. Localized heating in semiconductors is principally achieved through two processes: Shockley-Read-Hall and Auger recombination. Auger recombination is an inherent phenomenon that exhibits an upward trend when the bandgaps decrease. Shockley-Read-Hall recombination, defined as a trap-assisted procedure, arises from the existence of defects or impurities within a semiconductor material. When an electron-hole pair undergoes recombination, the absence of photon emission allows for the transfer of energy to either a higher electron in the conduction band or in the valence band as a deeper hole, as shown in Fig. 6b (right top). In the latter scenario, as illustrated in Fig. 6b (right bottom), electrons of the conduction band first relaxed in the trap level, followed by a transition to the valence band (the place of hole generation). The process of transferring thermal energy is initiated by the simultaneous relaxation of electrons93,94.

The third mechanism involves the generation of heat through thermal vibrations of atomic lattice primarily associated with the carbon-based nanomaterials38,39,40. The delocalization of electrons in the conjugated and/or hyper-conjugated system facilitates the electron’s excitation easily from HOMO (i.e., highest occupied molecular orbital) to LUMO (i.e., lowest unoccupied molecular orbital), thus enabling the absorption of light across a wide spectrum. An electron can elevate from HOMO to LOMO by receiving the matched light energy for its transition (Fig. 6c). A macroscopic increase in the material’s temperature occurs due to the relaxation of excited electrons via electron-phonon coupling, which transfers the absorbed light energy to vibrational modes throughout the atomic lattice.

Quantifying light to heat conversion

The capability of NPs to absorb incident light, produce heat, and transfer heat all play essential roles in the optimization of light conversion into heat. The different underlying physical mechanisms for light-to-heat conversion come with different mathematical formulations. Here, we present the most essential formulas for analyzing photothermal conversion regarding light absorption, heat generation, and heat transfer.

Light harvesting

When the surface of a material is subjected to electromagnetic radiation, a part of the photon energy can be absorbed. The light-absorption coefficient of NPs specifies the absorption ability of the incident photon energy. There are two fundamental factors that determine the energy absorbed by NPs: (1) the incoming wavelength range for absorption; and (2) the absorbance intensity for each wavelength. The total absorptance A (θ) for an incident light with angle (θ) can be defined as Eq. (1) (\({\lambda }_{\min }\): minimum wavelengths and \({\lambda }_{\max }\): maximum wavelengths of the incoming light, R (θ, λ): overall light reflectance, T (θ, λ): transmittance power, P (λ) (W/m2) overall light reflectance at wavelength λ)95,96.

Accordingly, decreasing the R (θ, λ) and T (θ, λ) results in an increase in light absorption. To achieve high conversion of light-to-heat efficiencies, light absorbers must be able to absorb a broad spectrum of light. The process of light absorption is determined by Beer-Lambert’s equation (Eq. (2)), representing an exponential decay having a cumulative behavior (\(I=\,{I}_{0}{e}^{-{kcl}}\) (W/m2): light intensity after the absorption, \({I}_{0}\): light intensity before absorption, k (M−1 cm−1): extinction coefficient, c (M): NPs concentration, l (cm): the optical path length).

By substituting I with \({I}_{0}{e}^{-{kcl}}\) in Eq. (2), the absorbance is therefore obtained from A = kcl, which depends on the intrinsic properties of the absorber, such as shape, material, and size. However, when we consider employing NPs for heat transfer in a very small volume of medium, mere absorbance consideration is the very macroscopic view. Therefore, we delve deeper to get physical insight into plasmonic heating.

The extinction coefficient depends on the extinction cross section (\({C}_{{ext}}\)) of NPs, which is expressed as \({C}_{{ext}}={C}_{{scat}}+{C}_{{abs}}\), Cscat: scattering cross-section, and Cabs: absorption cross-section. These two parameters, in turn, can be described in terms of the particle’s polarizability (α) of the NPs of radius R due to irradiation with an EM wave by Eqs. (3)–(5) (ε(ω): NPs frequency-dependent dielectric constant, \({\varepsilon }_{m}\): surrounding medium dielectric constant). Therefore, the dielectric constants and diameter of the NPs, as well as the surrounding medium dielectric constants, are factors affecting the polarizability97.

As described in Eq. (6), by considering the relationship between the heat power (Q) produced by NPs when exposed to an EM wave at a certain intensity \(({I}_{o})\), the importance of Cabs can be comprehended98:

Hence, at a certain EM wavelength, the heat generated by the NPs is directly proportional to their absorption cross-section.

In addition to the above discussion, we demonstrate the connection between light and NPs and the generation of heat through the Joule effect. The formula for the time-averaged heat power density q is provided below (J: electronic current density, E: electric field inside the NPs)99:

Using the relation between the polarization vector (P) and E; \(J=\partial P/\partial t\) and \(P={\varepsilon }_{o}(\varepsilon -1)\), for a monochromatic light of angular frequency (ω) can be expressed as: \(q=\frac{\omega }{2}\,{\varepsilon }_{o}{Im}\left\{\varepsilon \right\}{\left|E\right|}^{2}\). The heat power density within a NP is directly proportional to the square of the amplitude of the electric field. Poynting’s theorem states that the total heat power (Q) emitted by a NP may be calculated by integrating q over its volume (V).

The heat produced by a NP causes the temperature to rise in both the NP and its surrounding media as a result of heat diffusion. This can be expressed using the widely recognized general heat transfer Eq. (9) (ρ: the material’s density, Cp: specific heat capacity, T(r): absolute temperature, κ: surrounding medium thermal conductivity).

Conversion efficiency of light-to-heat

The photothermal conversion efficiency (η) is an important factor in quantifying the absorbed energy converted to heat for different plasmonic nanostructures. This parameter can be expressed as Eq. (10) (QT: total heat energy produced by the NPs, ET: total energy output of the incoming light, m (kg): mass of the NPs, c (J/kgK): specific heat capacity, ∆T (K): temperature change of the NPs during the radiation time (t (s)), p: power, A (m2): surface area of the incoming light)100,101.

In this procedure, to measure η, the entire incident light is considered for input energy. However, from the absorbed, scattered, reflected, and transmitted photons, only the absorbed photons have the ability to convert the energy (light to heat).

Moreover, as in this strategy, the transfer of heat from the photothermal material to the surroundings is not considered, which doesn’t solve the problem of heating a small volume of medium. So, the photothermal conversion efficiency η can be estimated by writing the heat balance equation102:

\(\sum m{C}_{p}\): summation of mass and heat capacities of all NPs,

\(\frac{{dT}}{{dt}}\): temperature increase rate,

\({Q}_{{ext}}\): external heat flux,

\({Q}_{{NP}}+{Q}_{{solvent}}\): heat produced by converting the absorbed light into heat by either NPs \({(Q}_{{NP}})\) or by the solvent \(({Q}_{{solvent}})\).

Estimating the heat loss to the media causes the temperature decay process once the incident light is removed. The QNP is defined using Eq. (12) in the switched-OFF light mode:

where Aλ is the absorbance at irradiation wavelength λ. In equilibrium conditions, \(\sum m{C}_{p}\frac{{dT}}{{dt}}=0\,\) and η can be calculated as Eqs. (13)–(15) (Qext: computable from experimental cooling kinetics, h: NPs’ heat transfer coefficient, A: for heat transfer surface area to surrounding media, \({T}_{{amb}}\): surroundings temperature, and T: current temperature).

The actual temperature equals the steady-state temperature \({T}=\,{T}_{\max }\,=\,{T}_{{amb}}\,+\,\varDelta T\) at equilibrium. These parameters can be estimated using the product of m and Cp and the cooling time coefficient (τc), of all the NPs. The absolute value of η will be influenced by a number of experimental circumstances. For example, factors that may significantly influence the determination of τc, the method of actual temperature measurement, will impact the sum of the product of mass and heat capacity.

Heat transfer

Another underlying part of the light-to-heat conversion is heat transfer, which is conducted by conduction, convection, and radiation mechanisms95,103. Heat conduction is the process of transferring heat from a warmer area to a cooler one. The heat conduction can be calculated as Eq. (16) (kNP (W/mK): NPs’ thermal conductivity, d (m): light absorber thickness).

Thermal convection involves the movement of a mass of fluid from the heating source into a cooler part of the fluid. In this way, heat transfer is caused by temperature variations within the fluid, and it is given as:

Lastly, thermal radiation refers to the radiation of EM waves by all objects without the need for any media. The Stefan-Boltzmann Law can be expressed for energy exchange between two regions with different temperatures as:

where ϵ represents the radiation coefficient, σ is Stefan’s coefficient (5.6703 × 108 Wm−2K−4); consequently, besides the physical characteristics of the NPs, their surrounding medium also affects the heat transfer. So, the conversion of light to heat can be improved by the appropriate selection of NPs and considering the condition of their surrounding medium.

Developments of Photothermal Nanomaterials

The application of a photothermal process starts with the selection of particular NPs. The principal phenomena governing this process are fundamentally different: metal NPs display the LSPR effect35,104, intrinsic semiconductors and lightly doped semiconductors show non-radiative relaxation91,92, and carbon nanostructures, including polymers, demonstrate thermal vibration-based heating assisted by the delocalization of π electron clouds105,106. However, this bifurcation is not sacrosanct, and even highly doped semiconductors can reveal LSPR56. Similarly, 2D materials can unveil the coupling of both LSPR and non-radiative relaxation107. Extensive research has been done to show the efficacy of an array of nanomaterials and compare them for their suitability as photothermal converters for applications in nucleic acid amplification in PCR108,109,110,111,112, sensors113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120, biomedica86,111,121,122, bioimaging123,124,125, superhydrophobic coating126,127, immunomagnetic bioassays128, optical nanothermometry129, atomic switches130, spectroscopy122,131, nanofabrication132,133, acoustic wave detection134, seawater desalination135,136, plasmonic photocatalysis137,138, strain modulation139, and plasmonic actuation140. Figure 7a–c graphically reviews some of the latest works and compare the photothermal conversion efficiency on metals, semiconductors, and carbon NPs, respectively.

Photothermal conversion by nanomaterials in biological applications: (a) photothermal efficiency of metal nanomaterials, including Au148,149,150,151,261,262,263,264, Pd265,266,267,268, Cu269,270,271,272,273, Mn274,275,276,277, Fe278,279,280,281,282, Ag264,283,284,285,286,287, WO288, Ni289, and core-shell structures153,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297; (b) photothermal efficiency of semiconductor nanomaterials, including MnOx298,299,300,301,302, FexOy303,304,305,306,307,308, Ag2S309,310,311,312, CuS313,314,315,316, WS2317,318,319, CuSe320,321,322, BiSe3323,324,325, FeS326,327,328, SnS2329,330, and nanocomposites331,332,333,334,335,336; (c) photothermal efficiency of carbon nanostructures, molecules, and polymers, including graphene and derivatives163,164,337,338,339,340,341,342, CNT343,344,345, carbon dots346,347,348,349,350,351,352, biomass155,353,354,355, polymers356,357,358,359, molecules360,361,362,363, and hybrid NPs364,365,366,367,368,369,370,371,372,373,374,375

A wide range of photothermal efficiencies is exhibited by the nanomaterials that significantly depend upon their size and/or morphology. These distinctions were clearly observed in several reports. The amplitude of the electron oscillation of Au nanospheres rises with an increase in particle size that shifts the LSPR towards the lower energy side and eventually controls the localized heating141,142. Apart from size, the morphology of Au NPs exhibits a vital role in modifying the LSPR energy; these structural variations include preparing them into nanorods143,144, nanostars145, or nanoshells146,147. The latter is manifested by the photothermal efficiency of Au hollow rods, with an efficiency of about 99%148, whereas Au nanospheres and Au nanorods exhibited efficiencies of 54% and 41%, respectively149,150,151. The phenomenon of reabsorption has been proposed as a possible explanation for such high efficiency in hollow rods148,152. Moreover, there are also reports for core-shell structure; for example, when Au is combined with Ag in Ag core@Au shell, it showed a photothermal efficiency of 87.2%153. Though the efficiency of such a structure is less than the maximum reported, it gives various applications a range of efficiencies. It is apparent that photothermal efficiency changes not only with the change of materials but also with morphology and size. The effect of size and morphology on photothermal efficiency was meticulously tabulated by Zhuoqian et al.154. Photothermal efficiency is similarly tunable in semiconductor and carbon-based photothermal nanomaterials, as shown in Fig. 7b, c. Importantly, from the comparison in Fig. 7, carbon nanostructures, molecules, and polymers are not far behind metals in photothermal efficiency. In some cases, biomass precursor-based carbon nanostructures showed similar efficiency in generating heat for solar water evaporation to their metal counterparts, such as 99% in PPy decorated cattail fiber (CF) foam155. This is a promising development, as cattail fiber is an aquatic plant that can spread swiftly and provide abundant biomass lignocellulose. Based on this summary of various nanomaterials as photothermal converters, selecting the materials for advanced applications becomes easier.

In this work, we focus on the selection of NPs for nucleic acid amplification in PCR. For this application, we are specifically interested in controlling the heating rate and cooling rate and the time required to complete the total number of thermal cycles before a positive result can be reported. For ultrafast thermocycling using nanomaterials, the NPs’ material type, size, and morphology are key, and they have been well-documented over the last decade156. Efficient photothermal conversion can be achieved by tuning the LSPR to the desired spectral window in the case of metals. Similarly, in order to control the non-radiative relaxation in semiconductor particles, the band gap and charge trapping states can again be tuned by size and shape157,158,159,160. In Table 3, the performance of a set of nanomaterials for use in PCR is compared. Au NP-based thermal cycling remains the most popular choice among researchers and manufacturers. Nevertheless, the volatile thermodynamic characteristics of Au nanorods at elevated temperatures render them inappropriate as constituents for continuous heat-transfer agents, hence posing a significant obstacle to Au NP-based PCR. Noble metal nanostructure-based thermal cycling has been reported so far to be accomplished within 1200 seconds to 54 seconds with Au nanorods161,162.

On the other hand, semiconductors exhibit resistance to elevated temperatures due to their inherent thermal stability and offer a certain degree of advantage in terms of thermal stability. However, semiconductor-based thermal cycling is found to be time-consuming compared to its counterpart metal and carbon nanostructures. In order to achieve photothermal cyclers using cost-effective and easily expandable materials, electron-rich carbon nanostructures are a suitable alternative to noble metals. This occurs because the interaction between incoming photons and the numerous π electrons in the conjugated system considerably leads to thermal energy dissipation. The incoming photons trigger electronic transitions and induce resonance in the oscillation of π electron clouds. This leads to vibrational changes, which help electrons and phonons as well as phonon interactions within the carbon nanomaterial. Hence, this enhances the formation of electron-phonon pairs and ultimately improves photothermal conversion efficiency through thermal vibrations163,164,165,166,167. Moreover, the carbon nanostructure-based PCR has a significantly comparable thermal cycling time with metals and is better than the semiconductor shown in Table 3. Though carbon-based photothermal materials exhibit high photothermal conversion efficiencies comparable to metallic counterparts and better than semiconductor NPs. However, Au NP-based thermal cycling continues to be the preferred option for researchers and manufacturers. Nonetheless, the compatibility of carbon-based thermal cycling remains in its nascent phase for integration with the current PCR. The predominant rationale for the majority of documented work on thermal cycling is the utilization of Au NPs, recognized for their tunable plasmonic and biocompatibility. Therefore, selecting materials for PCR applications not only focuses on the photothermal conversion efficiency but also needs a holistic approach that converges all the parameters to achieve ultrafast diagnostic devices.

Beyond the traditional materials documented thus far for applications in photothermal energy conversion, there exists a novel class of emerging materials that holds significant promise for utilization as thermoplasmonic materials. Within the framework of plasmonic science and engineering, the use of artificially engineered materials and metamaterials has been proposed. The use of artificially engineered materials has been explored since the 1940s and 1950s in order to emulate effective media parameters following Drude-Lorentz models, applicable to radar lenses, refractive index variations, or delay lines, among others168,169,170. Further on, Victor Veselago171 studied the theoretical properties of materials that could have any combination of values of effective ε and µ, either positive or negative, leading to double negative ε and µ materials, not encountered in nature. These materials exhibit unusual properties such as anti-parallel phase and group velocity (for which these materials are also called Left Handed Materials, LHM, in contrast to conventional materials), inversion of Snell’s law, and inversion of Cerenkov radiation, among others. However, these new artificial materials, termed metamaterials, aren’t readily available in nature, so they must be artificially engineered, with the first practical implementations within the microwave spectrum proposed in the early 2000s172. From that point, a relevant amount of results related to metamaterials has been reported, in which multiple frequency bands from acoustics up to UV and different application domains173,174. Among the different metamaterial configurations, 2D metasurfaces and 3D configurations (mainly based on 2D structure stacking) have attracted attention, owing to their flexibility to be employed in order to enhance sensing capabilities, improve stealthing, or provide agile communication systems, to name a few175,176,177. In relation to plasmonics, metamaterials have been employed in order to enhance detection mainly by increasing field values aided by inherent lensing and focusing properties, for example, in chiral media178, controlling light intensity and polarization in molecular plasmonics179, or nanochemistry applications180. Taking advantage of the capability of adapting the 2D/2D stacking configurations of artificially engineered structures, such as layers of discs, rods, or resonant structures, the aforementioned field enhancement properties of metamaterials/metasurfaces have also been explored in relation to thermoplasmonics. A broadband solar light absorber based on Cu metal nanostructure fabricated on the surface of a Palash leaf aided by pulsed layer deposition is described in181. The use of nanoholes within metal structures is analyzed in182, in terms of practical variations in hole diameter as well as metal layer thickness and non-ideal conditions given by material properties and/or fabrication process. Advances in the use of thermoplasmonic and photothermal metamaterials in the field of solar energy are described in183, including photonic crystal–based thermal emitter technology, the use of rare earth ion–doped luminescent materials or rare earth ion–doped glass emitters, and semiconductor emitters with plasmonic nanogratings, among others. Hyperbolic metamaterials within the NIR-II and NIR-III are described in184, providing higher temperature increases as compared to conventional Au nano-disk configurations for application within biomedical diagnostics. Dynamic control of metasurface properties within the optical domain is proposed in185, aided by the use of liquid crystal technology, within the 750–770 nm wavelength region.

Microfluidic-based PCR using light-to-heat conversion

Microfluidic platforms as miniaturized devices have been employed to integrate several laboratory functions on a single chip and manipulate small volumes of fluids in microchannels186,187. Microfluidic-based technologies offer numerous advantages, such as minimal sample requirements, inexpensive fabrication, adaptability, shortened analysis time, portability, and automation188,189. However, at the microscale level, microfluidics has some drawbacks, where capillary forces, surface roughness, and chemical interactions between materials can become more significant190,191. This might lead to experimental complications that are uncommon with traditional lab equipment. Furthermore, due to the small scale of microfluidic devices, the signals generated are typically very small, and the background noise can be relatively high192,193. This can make distinguishing a signal from the noise challenging, resulting in inaccurate measurements. Consequently, to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio and ensure accuracy, optimizing microfluidic devices and detection methods is crucial194. Despite these challenges, microfluidics is becoming more popular worldwide, with the increasing demand for portable, easy-to-use point-of-care (POC), and compact devices that can perform more rapid and affordable diagnostic testing195,196. Scientists have recently shown great interest in integrating microfluidic systems with PCR techniques using light-to-heat conversion for biology applications to recognize viruses and bacterial diseases through the amplification of pathogen molecules110,197,198. They used light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as heat sources in microfluid-based PCR techniques because of their fast heat transfer properties, low power consumption, and affordable price110.

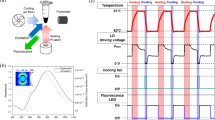

A remarkable achievement using an ultrafast photonic PCR thermal cycler was demonstrated, in which 30 thermal cycles were completed within 5 min with an ultrafast heating rate of 12.79 °C/s and a cooling rate of 6.6 °C/s110. This was made possible by combining a 120 nm-thick Au film, which served as a converter of light to heat, and LEDs with a power intensity of only 3.5 W, as the source of heat (Fig. 8a). The thin Au film used in the experiment was found to have an impressive light absorption rate of 65% and the ability to rapidly heat the surrounding medium to 150 °C within just 3 min. While properties such as low power intensity, high-speed thermal cycling, and the ability for easy incorporation into existing systems made this method a promising candidate for POC diagnostic applications, its relatively low amplification efficiency, which was based on the non-uniform temperature distribution under a single two-dimensional heater, needed to be improved. Lee et al. utilized an LED-driven optical cavity with two thin Au films with different thicknesses (120/10 nm for the top/bottom film) to provide a more uniform temperature distribution during PCR thermal cycling (Fig. 8b)197. According to the results, the temperature distribution of the PCR reagents became effectively uniform, with a difference of 1.9/0.2 °C at temperatures of 94/60 °C. Additionally, 30 thermal cycles were rapidly completed within only 4–10 min for different sample volumes of 1.3–10 µL. Furthermore, this method successfully amplified nucleic acids (c-MET cDNA), even at low concentrations of 10−8 ng/µL, by 40 cycles of cavity PCR. This remarkable efficiency was achieved within a short time frame of 15 min, highlighting the method’s potential as a fast and reliable solution for nucleic acid amplification. Subsequently, they employed a combination of three techniques on a chip, including filtering, lysis, and PCR, for rapidly identifying bacterial pathogens in urine samples (Fig. 8c)198. The nanoporous membranes coated with titanium (Ti) (5 nm) and Au (80 nm) utilized in this platform have a dual function: they not only concentrate bacteria but also function as a photothermal actuator. Two LEDs with λ = 447.5 nm and P = 890 mW were employed for measuring temperature and testing the E. coli bacteria in the sample. With remarkable efficiency, this system achieved bacterial enrichment of up to 40,000-fold within just 2 min, with a capture efficiency rate of over 90%. It also provided on-site photothermal lysing and initial denaturation in just 3 min, followed by nucleic acid amplification within a further 10 min. Finally, bacterial pathogens in urine samples were detected in less than 20 min. They successfully detected bacteria at low concentrations (103 CFU/mL) using this nanophotonic PCR system. However, in comparison with a traditional benchtop thermocycler, their system resulted in a lower intensity of the specific band (the desired DNA fragment size). They proposed that this difference in DNA amplification efficiency may stem from the fact that their system relies on a two-stage fast thermocycling method, which can potentially result in a lower amplification efficiency compared to a more traditional three-step thermocycling method commonly used in benchtop thermocyclers. Similarly, Lee et al. demonstrated strong laser energy absorption by the Au-deposited glass fiber membranes (Fig. 8d)199. Glass fibers were selected for the study due to their superior absorption capacity over other materials, and the study also investigated mixed-matrix membranes, nitrocellulose, polyether sulfone, and vivid plasma membranes with an area of 4 mm2. Using 25 rapid thermal cycles between the solution temperatures of 63 °C and 95 °C, PCR was completed in 6 min. Next, in 12 min, the amplified samples on the membrane were successfully examined using SYBR fluorescent signal assessment. In another study, a thin 120-nm-thick Au film deposited on a PMMA substrate was employed to act as the PCR reaction’s heating source200. Non-homogeneous temperature distribution in the reaction chamber is one of the primary disadvantages of certain plasmonic PCR thermal cyclers, particularly those that utilize a plasmonic film instead of plasmonic NPs. Therefore, they added TiO2 NP suspensions, with a 0.4 nM optimal concentration to solve the problem of the chamber’s non-homogeneous temperature by improving the sample’s thermal conductivity. A 10 W blue LED with a peak wavelength of 447.5 nm and a thermoelectric cooler (Peltier) module make up the thermal cycler’s heating and cooling components, respectively. The rates of cooling and heating are 2.65 °C/s and 4.44 °C/s, respectively. In 2020, plasmonic nanopillar arrays (PNAs) were employed for a rapid diagnostics system (Fig. 8e)201. The PNAs consist of Au nanoislands with nanogaps on glass nanopillar arrays (GNAs). In this study, 500 nm thick hydrogen silsesquioxane (HSQ) resin was spin-coated onto the PNAs to create a passivation layer. Since electrically charged Au nanoislands disrupt the reaction by attracting PCR components like Taq polymerase, the HSQ layer acts as a dielectric passivation layer to stop the PCR reaction from being inhibited. They were able to perform 30 thermal cycles between 98 °C and 60 °C in 3 min and 30 s using a single white LED light as an excitation source. The nanoplasmonic PCR chip has also demonstrated the rapid amplification of λ-DNA with an initial concentration of 0.1 ng/µL in 20 cycles and complementary DNA (cDNA) with an initial concentration of 0.1 ng/µL in 30 thermal cycles. The PNAs demonstrate remarkable light absorption with a 2.3-times increase compared to a thin Au film when exposed to white LED illumination. Similarly, GNAs containing Au nanoislands were coated by HSQ for an ultrafast PCR (Fig. 8f)202. They obtained a 91% amplification efficiency, a heating rate of 11.95 °C/s, and a cooling rate of 7.31 °C/s. In contrast to traditional benchtop qPCR systems, the overall run time of this system is around 12 times quicker for 40 cycles of PCR. In another study, after the creation of nanoisland masks and the formation of nanoplasmonic substrate (NPS) by heat evaporation of an Au layer (40 nm) covering the GNAs’ top and sidewalls, silicon dioxide (SiO2) with a thickness of 500 nm was applied to reduce the surface roughness (Fig. 8g)203. They employed a plastic-on-metal (PoM) thin film cartridge that consists of an aluminum (Al) thin film layer, an adhesive layer, and a polypropylene (PP) layer to improve the heat transition and the real-time quantification without any spectral crosstalk during the plasmonic thermocycling. In this study, the heating and cooling rates of the Al thin film were 2.9 and 3.2 times faster than those of the plastic-on-glass (PoG) cartridge, respectively, with a ramping-up rate of 18.85 °C/s and a ramping-down rate of 8.89 °C/s. This system facilitated rapid molecular diagnosis of COVID-19 within just 10 min, incorporating a 210-second RT process and a 400-second amplification process for 40 PCR cycles. This system exhibited high amplification efficiency (over 95%), high classification accuracy (over 95%), and high total percent agreement of clinical tests (over 90%). In 2024, after coating polycarbonate (PC) with PDA, PEI was bonded to the substrate to trap the citrate-capped Au NPs that are negatively charged (Fig. 8h)204. Afterward, the surface coated with PDA, PEI, and Au NPs was then electrolessly deposited with Au. Next, a closed-chamber PCR chip was used to successfully amplify a target by employing a white LED. Using the PDA-mediated technique for coating in this study, the reaction time was 12 min to replicate 34 PCR cycles.

Photonic thermocycler with (a) a light-to-heat converter comprised of a thin Au film. Reprinted from ref. 110, with permission from Springer Nature; (b) an LED-based system that incorporates two thin Au films into an optical cavity. Reprinted from ref. 197, with permission from John Wiley and Sons; (c) an Au-coated nanoporous membrane. Reprinted from ref. 198, with permission from the American Chemical Society; (d) Au-deposited glass fiber membranes. Reprinted with permission from ref. 199. Copyright 2022 Elsevier; (e) a microfluidic chip made by joining the HSQ-coated PNAs substrate to the polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). Reprinted from ref. 201, with permission from the American Chemical Society; (f) a microfluidic chip made by joining the HSQ-coated PNAs substrate to the bilayered PDMS. Reprinted from202, available under Attribution CC BY-NC-ND 4.0; (g) a plastic-on-metal (PoM) thin film cartridge made by joining the SiO2-coated PNAs substrate to the Al thin film layer. Reprinted from ref. 203, available under Attribution CC BY-NC-ND 4.0; (h) an Au NP coating using PDA204

Table 4 compares papers that employed a plasmonic mechanism for PCR reactions in microfluidics. Au nanoislands applied to glass pillars show outstanding photothermal efficiency and extensive absorption in visible light areas. It has also shown a significant increase in both the heating and cooling rates with the maximum values of 18.85 °C/s and 12.4 °C/s, respectively. Nevertheless, the Au layers in these investigations were created utilizing costly equipment-intensive physical deposition methods (electron beam evaporation or thermal evaporation). The Au NP coating using PDA is more applicable in a wider range of scenarios because it does not require costly equipment, unlike physical deposition approaches.

Conclusion

In summary, we presented a detailed review of nanoPCR, photothermal PCR, and on-chip photothermal PCR applications. The PCR system has incorporated various classes of nanomaterials to date, significantly reducing reaction time, expanding the annealing temperature range, increasing product yield and amplification efficiency, enhancing detection sensitivity, reducing non-specific products, and improving the detection rate. For instance, Au NPs with size ranges of 1-100 nm are the most commonly used metal NPs in PCR. They were found to have a sensitivity up to 1000-fold greater than conventional PCR. The maximum optimal concentration of Au NP used in the PCR process is 0.4 mM. They could enhance the detection rate to approximately 77%. Studies have shown that TiO2-based nanoPCRs, at optimal concentrations of 0.2 g/L and 0.4 nM, can significantly reduce the overall PCR time by up to 50%. Introducing SWCNTs and MWCNTs with an optimal concentration of 1 g/L to PCR reagents was determined to be a suitable option to increase the efficiency and specificity of long PCR (14.3 kb). SWCNTs were also found to increase the PCR yield with an optimal concentration of 3 g/L. Fe3O4 NPs with a very low optimal concentration of 0.72 × 10-2 nM were reported to result in a 190% increase in the PCR yield compared to the PCR reaction without NPs. ZnO nanoflowers and SCM are another type of NP, characterized by a larger size (1 µm), which increase the sensitivity and specificity of the PCR process. The unique photothermal properties of NPs and their physicochemical properties can enable scientists to progress in robust, portable, and ultrafast PCR at the POC level. To date, NPs such as metals, semiconductors, and carbons have demonstrated different ranges of photothermal efficiencies for various applications based on their materials, morphology, and size. Using plasmonic localized heating in metals, non-radiative relaxation in semiconductors, and thermal vibration of carbon molecules, PCR applications have achieved rapid and efficient amplifications. Considering the heating rate, cooling rate, and total PCR time as main factors in PCR, the Au nanorod with dimensions of D = 10 nm and L = 41 nm is better than the rest with a significant margin. Besides, carbon nanostructure-based PCRs perform better than semiconductors in terms of thermal cycling time. Microfluidics-based PCRs have utilized certain metallic NPs to take advantage of plasmonic -controlled heating. Nevertheless, the extensive capacity for effective conversion of light into heat and the utilization of NPs in PCR remain largely untapped. This is an opportunity to enhance the microfluidic PCR by including a wide range of advanced nanomaterials, thereby satisfying the need for the development of ultrafast PCR.

Microfluidics-based PCRs have recently utilized only a limited number of metals with plasmonic localized heating. Despite the advantages of light-to-heat conversion and the photothermal efficiencies of NPs, only a limited number of devices use light-to-heat conversion in microfluidics systems. Integrating photothermal effects and microfluidic fields for PCR will be essential to overcome existing challenges. Most of the applications are adopted with Au NPs for thermal cycling, but we have observed that even carbon NPs have shown a significant photothermal conversion efficiency, and they are biocompatible, easy to fabricate, and inexpensive. These attributes suggest that the application of carbon-based nanomaterials could be of potential advantage for thermal cycling in the future. In order to immobilize and create metal NPs that allow photothermal heating of surfaces, intermediate layers can be substituted for expensive, equipment-intensive physical deposition techniques like thermal evaporation or electron beam evaporation, which are not accessible to all researchers.

References

Elizaquı́vel, P., Aznar, R. & Sánchez, G. Recent developments in the use of viability dyes and quantitative PCR in the food microbiology field. J. Appl. Microbiol. 116, 1–13 (2014).

Kuypers, J. & Jerome, K. R. Applications of digital PCR for clinical microbiology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 55, 1621–1628 (2017).

Matheson, C. D. et al. Removal of metal ion inhibition encountered during DNA extraction and amplification of copper-preserved archaeological bone using size exclusion chromatography. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 140, 384–391 (2009).

Singh, J., Birbian, N., Sinha, S. & Goswami, A. A critical review on PCR, its types and applications. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 1, 65–80 (2014).

Madadelahi, M., Agarwal, R., Martinez-Chapa, S. O. & Madou, M. J. A roadmap to high-speed polymerase chain reaction (PCR): COVID-19 as a technology accelerator. Biosens. Bioelectron. 246, 115830 (2023).

Vajpayee, K., Dash, H. R., Parekh, P. B. & Shukla, R. K. PCR inhibitors and facilitators—their role in forensic DNA analysis. Forensic Sci. Int. 349, 111773 (2023).

Akane, A. et al. Purification of forensic specimens for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. J. Forensic Sci. 38, 691–701 (1993).

Al-Soud, W. A. & Radstrom, P. Purification and characterization of PCR-inhibitory components in blood cells. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 485–493 (2001).

Al-Soud, W. A., Jönsson, L. J. & Rådström, P. Identification and characterization of im- munoglobulin G in blood as a major inhibitor of diagnostic PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 345–350 (2000).

Eckhart, L., Bach, J., Ban, J. & Tschachler, E. Melanin binds reversibly to thermostable DNA polymerase and inhibits its activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 271, 726–730 (2000).

Yoshii, T., Tamura, K., Taniguchi, T., Akiyama, K. & Ishiyama, I. Water-soluble eumelanin as a PCR-inhibitor and a simple method for its removal. Nihon Hoigaku Zasshi= Jpn. J. Leg. Med. 47, 323–329 (1993).

Katcher, H. & Schwartz, I. A distinctive property of Tth DNA polymerase: enzymatic amplification in the presence of phenol. Biotechniques 16, 84–92 (1994).

Tsai, Y.-L. & Olson, B. Rapid method for separation of bacterial DNA from humic substances in sediments for polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 2292–2295 (1992).

Bélec, L. et al. Myoglobin as a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) inhibitor: a limitation for PCR from skeletal muscle tissue avoided by the use of thermus thermophilus polymerase. Muscle Nerve 21, 1064–1067 (1998).

Kim, C.-H. et al. Optimization of the PCR for detection of Staphylococcus aureus nuc gene in bovine milk. J. Dairy Sci. 84, 74–83 (2001).

Bickley, J., Short, J., McDowell, D. & Parkes, H. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of Listeria monocytogenes in diluted milk and reversal of PCR inhibition caused by calcium ions. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 22, 153–158 (1996).

Monteiro, L. et al. Complex polysaccharides as PCR inhibitors in feces: Helicobacter pylori model. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35, 995–998 (1997).

Demeke, T. & Adams, R. P. The effects of plant polysaccharides and buffer additives on PCR. Biotechniques 12, 332–334 (1992).

Khan, G., Kangro, H., Coates, P. & Heath, R. Inhibitory effects of urine on the polymerase chain reaction for cytomegalovirus DNA. J. Clin. Pathol. 44, 360–365 (1991).

Yuce, M., Kurt, H., Mokkapati, V. R. & Budak, H. Employment of nanomaterials in polymerase chain reaction: insight into the impacts and putative operating mechanisms of nano- additives in PCR. RSC Adv. 4, 36800–36814 (2014).

Khan, I., Saeed, K. & Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 908–931 (2019).

Yang, W., Li, X., Sun, J. & Shao, Z. Enhanced PCR amplification of GC-rich DNA templates by gold nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 5, 11520–11524 (2013).

Rehman, A. et al. Metal nanoparticle assisted polymerase chain reaction for strain typing of Salmonella typhi. Analyst 140, 7366–7372 (2015).

Cui, D., Tian, F., Kong, Y., Titushikin, I. & Gao, H. Effects of single-walled carbon nanotubes on the polymerase chain reaction. Nanotechnology 15, 154 (2003).

Zhang, Z., Wang, M. & An, H. An aqueous suspension of carbon nanopowder enhances the efficiency of a polymerase chain reaction. Nanotechnology 18, 355706 (2007).

Madadelahi, M., Ghazimirsaeed, E. & Shamloo, A. Design and fabrication of a two-phase diamond nanoparticle aided fast PCR device. Analytica Chim. Acta 1068, 28–40 (2019).

Jia, J., Sun, L., Hu, N., Huang, G. & Weng, J. Graphene enhances the specificity of the polymerase chain reaction. Small 8, 2011–2015 (2012).

Nie, L., Gao, L., Yan, X. & Wang, T. Functionalized tetrapod-like ZnO nanostructures for plasmid DNA purification, polymerase chain reaction and delivery. Nanotechnology 18, 015101 (2006).

Li, S. et al. Impact and mechanism of TiO2 nanoparticles on DNA synthesis in vitro. Sci. China Ser. B: Chem. 51, 367–372 (2008).

Wang, Y., Wang, F., Wang, H. & Song, M. Graphene oxide enhances the specificity of the polymerase chain reaction by modifying primer-template matching. Sci. Rep. 7, 16510 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. Effects of quantum dots in polymerase chain reaction. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 7637–7641 (2009).

Almond, D. P. & Patel, P. Photothermal Science and Techniques (Springer Science & Business Media, 1996).

Cui, X. et al. Photothermal nanomaterials: a powerful light-to-heat converter. Chem. Rev. 123, 6891–6952 (2023).

Jauffred, L., Samadi, A., Klingberg, H., Bendix, P. M. & Oddershede, L. B. Plasmonic heating of nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 119, 8087–8130 (2019).

Kim, M., Lee, J.-H. & Nam, J.-M. Plasmonic photothermal nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900471 (2019).

Huang, X. et al. Design and functionalization of the NIR-responsive photothermal semiconductor nanomaterials for cancer theranostics. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2529–2538 (2017).

Kriegel, I., Scotognella, F. & Manna, L. Plasmonic doped semiconductor nanocrystals: properties, fabrication, applications and perspectives. Phys. Rep. 674, 1–52 (2017).

Panwar, N. et al. Nanocarbons for biology and medicine: sensing, imaging, and drug delivery. Chem. Rev. 119, 9559–9656 (2019).

Hong, G., Diao, S., Antaris, A. L. & Dai, H. Carbon nanomaterials for biological imaging and nanomedicinal therapy. Chem. Rev. 115, 10816–10906 (2015).

Wang, B. et al. Carbon dots as a new class of nanomedicines: opportunities and challenges. Coord. Chem. Rev. 442, 214010 (2021).

Du, J., Xu, N., Fan, J., Sun, W. & Peng, X. Carbon dots for in vivo bioimaging and theranostics. Small 15, 1805087 (2019).

Jung, H. S. et al. Organic molecule-based photothermal agents: an expanding photothermal therapy universe. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 2280–2297 (2018).

Zhao, L., Liu, Y., Xing, R. & Yan, X. Supramolecular photothermal effects: a promising mechanism for efficient thermal conversion. Angew. Chem. 132, 3821–3829 (2020).

Cai, G., Yan, P., Zhang, L., Zhou, H.-C. & Jiang, H.-L. Metal–organic framework-based hierarchically porous materials: synthesis and applications. Chem. Rev. 121, 12278–12326 (2021).

Chakraborty, G., Park, I.-H., Medishetty, R. & Vittal, J. J. Two-dimensional metal-organic framework materials: synthesis, structures, properties and applications. Chem. Rev. 121, 3751–3891 (2021).

Wang, Q. & Astruc, D. State of the art and prospects in metal–organic framework (MOF)- based and MOF-derived nanocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 120, 1438–1511 (2019).

Xiao, J.-D. & Jiang, H.-L. Metal–organic frameworks for photocatalysis and photothermal catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 356–366 (2018).

Lan, G., Ni, K. & Lin, W. Nanoscale metal–organic frameworks for phototherapy of cancer. Coord. Chem. Rev. 379, 65–81 (2019).

VahidMohammadi, A., Rosen, J. & Gogotsi, Y. The world of two-dimensional carbides and nitrides (MXenes). Science 372, eabf1581 (2021).

Hantanasirisakul, K. & Gogotsi, Y. Electronic and optical properties of 2D transition metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes). Adv. Mater. 30, 1804779 (2018).

Szuplewska, A. et al. Future applications of MXenes in biotechnology, nanomedicine, and sensors. Trends Biotechnol. 38, 264–279 (2020).

Mi, Z. et al. Stable radical cation-containing covalent organic frameworks exhibiting remarkable structure-enhanced photothermal conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 14433–14442 (2019).

Ma, H.-C., Zhao, C.-C., Chen, G.-J. & Dong, Y.-B. Photothermal conversion triggered thermal asymmetric catalysis within metal nanoparticles loaded homochiral covalent organic framework. Nat. Commun. 10, 3368 (2019).

Xia, R. et al. Nanoscale covalent organic frameworks with donor–acceptor structure for enhanced photothermal ablation of tumors. ACS Nano 15, 7638–7648 (2021).

Tan, J. et al. Manipulation of amorphous-to-crystalline transformation: Towards the construction of covalent organic framework hybrid microspheres with NIR photothermal conversion ability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 13979–13984 (2016).

Agrawal, A. et al. Localized surface plasmon resonance in semiconductor nanocrystals. Chem. Rev. 118, 3121–3207 (2018).

Georgakilas, V., Perman, J. A., Tucek, J. & Zboril, R. Broad family of carbon nanoallotropes: classification, chemistry, and applications of fullerenes, carbon dots, nanotubes, graphene, nanodiamonds, and combined superstructures. Chem. Rev. 115, 4744–4822 (2015).

Li, Z., Lei, H., Kan, A., Xie, H. & Yu, W. Photothermal applications based on graphene and its derivatives: a state-of-the-art review. Energy 216, 119262 (2021).

Zhao, L., Liu, Y., Chang, R., Xing, R. & Yan, X. Supramolecular photothermal nanomaterials as an emerging paradigm toward precision cancer therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806877 (2019).

Kim, H. J., Kim, B., Auh, Y. & Kim, E. Conjugated organic photothermal films for spatiotemporal thermal engineering. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005940 (2021).

He, W. et al. Structure development of carbon-based solar-driven water evaporation systems. Sci. Bull. 66, 1472–1483 (2021).

Yang, S.-M., Lv, S., Zhang, W. & Cui, Y. Microfluidic point-of-care (POC) devices in early diagnosis: a review of opportunities and challenges. Sensors 22, 1620 (2022).

Liu, H., Dao, T. N. T., Koo, B., Jang, Y. O. & Shin, Y. Trends and challenges of nanotechnology in self-test at home. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 144, 116438 (2021).

Bartosik, M. et al. Advanced technologies towards improved HPV diagnostics. J. Med. Virol. 96, e29409 (2024).

Xin, H., Namgung, B. & Lee, L. P. Nanoplasmonic optical antennas for life sciences and medicine. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 228–243 (2018).

Rådström, P., Löfström, C., Lövenklev, M., Knutsson, R. & Wolffs, P. Strategies for overcoming PCR inhibition. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2008, pdb–top20 (2008).

Yang, Z. et al. Application of nanomaterials to enhance polymerase chain reaction. Molecules 27, 8854 (2022).

Lou, X. & Zhang, Y. Mechanism studies on nanoPCR and applications of gold nanoparticles in genetic analysis. ACS Appl. Mater. interfaces 5, 6276–6284 (2013).

Li, M., Lin, Y.-C., Wu, C.-C. & Liu, H.-S. Enhancing the efficiency of a PCR using gold nanoparticles. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e184–e184 (2005).

Yuan, L. & He, Y. Effect of surface charge of PDDA-protected gold nanoparticles on the specificity and efficiency of DNA polymerase chain reaction. Analyst 138, 539–545 (2013).

Li, A. et al. Mechanistic studies of enhanced PCR using PEGylated PEI-entrapped gold nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 25808–25817 (2016).

Jeong, H. Y. et al. A hybrid composite of gold and graphene oxide as a PCR enhancer. RSC Adv. 5, 93117–93121 (2015).

Fu-Ming, S., Xin, L. & Jia, L. Development of nano-polymerase chain reaction and its application. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 45, 1745–1753 (2017).

Ye, J. et al. Development of a triple NanoPCR method for feline calicivirus, feline panleukopenia syndrome virus, and feline herpesvirus type I virus. BMC Vet. Res. 18, 379 (2022).

Vanzha, E. et al. Gold nanoparticle-assisted polymerase chain reaction: effects of surface ligands, nanoparticle shape and material. RSC Adv. 6, 110146–110154 (2016).

Uysal, E. Impacts of Single-walled Carbon Nanotubes on Polymerase Chain Reaction. PhD thesis, Technological University Dublin (2015).

Liu, P., Guan, R., Liu, M. & Huang, G. et al. Effect of PCR amplification with nano-silver on DNA synthesis and its mechanism. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 18, 876–881 (2010).

Hwang, S.-H. et al. Effects of upconversion nanoparticles on polymerase chain reaction. PLoS ONE 8, e73408 (2013).

Hu, C. et al. Graphene oxide-based qRT-PCR assay enables the sensitive and specific detection of miRNAs for the screening of ovarian cancer. Analytica Chim. Acta 1174, 338715 (2021).

Lenka, G. & Weng, W.-H. Nanosized particles of titanium dioxide specifically increase the efficency of conventional polymerase chain reaction. Digest J. Nanomater. Biostruct. (DJNB) 8 (2013).

Shen, C. et al. NanoPCR observation: different levels of DNA replication fidelity in nanoparticle-enhanced polymerase chain reactions. Nanotechnology 20, 455103 (2009).

Willets, K. A. & Van Duyne, R. P. Localized surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy and sensing. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 58, 267–297 (2007).

Mayer, K. M. & Hafner, J. H. Localized surface plasmon resonance sensors. Chem. Rev. 111, 3828–3857 (2011).

Zheng, J. et al. Gold nanorods: the most versatile plasmonic nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 121, 13342–13453 (2021).

Ha, M. et al. Multicomponent plasmonic nanoparticles: from heterostructured nanoparticles to colloidal composite nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 119, 12208–12278 (2019).

Deng, Z. et al. The emergence of solar thermal utilization: solar-driven steam generation. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 7691–7709 (2017).

Stoneham, A. Non-radiative transitions in semiconductors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 44, 1251 (1981).

Liu, X. et al. Noble metal–metal oxide nanohybrids with tailored nanostructures for efficient solar energy conversion, photocatalysis and environmental remediation. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 402–434 (2017).

Coughlan, C. et al. Compound copper chalcogenide nanocrystals. Chem. Rev. 117, 5865–6109 (2017).

Woods-Robinson, R. et al. Wide band gap chalcogenide semiconductors. Chem. Rev. 120, 4007–4055 (2020).

Chen, X., Liu, L., Yu, P. Y. & Mao, S. S. Increasing solar absorption for photocatalysis with black hydrogenated titanium dioxide nanocrystals. Science 331, 746–750 (2011).

Wang, J. et al. High-performance photothermal conversion of narrow-bandgap Ti2O3 nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 29, 1603730 (2017).

Shockley, W. & Read, W. Jr. Statistics of the recombinations of holes and electrons. Phys. Rev. 87, 835 (1952).

Ghoussoub, M., Xia, M., Duchesne, P. N., Segal, D. & Ozin, G. Principles of photothermal gas-phase heterogeneous CO2 catalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1122–1142 (2019).

Zhu, L., Gao, M., Peh, C. K. N. & Ho, G. W. Solar-driven photothermal nanostructured materials designs and prerequisites for evaporation and catalysis applications. Mater. Horiz. 5, 323–343 (2018).

Cheng, P., Wang, D. & Schaaf, P. A review on photothermal conversion of solar energy with nanomaterials and nanostructures: from fundamentals to applications. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 6, 2200115 (2022).

Ye, E. & Li, Z. Photothermal Nanomaterials (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2022).

Cunha, J. et al. Controlling light, heat, and vibrations in plasmonics and phononics. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 2001225 (2020).

Baffou, G. in Thermoplasmonics: Heating Metal Nanoparticles Using Light 36–80 (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Zeng, J., Goldfeld, D. & Xia, Y. A plasmon-assisted optofluidic system for measuring the photothermal conversion efficiencies of gold nanostructures and controlling an electrical switch. Angew. Chem. (Int. ed. Engl.) 52, 4169 (2013).

Xiao, L., Chen, X., Yang, X., Sun, J. & Geng, J. Recent advances in polymer-based photothermal materials for biological applications. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2, 4273–4288 (2020).

Paściak, A., Pilch-Wróbel, A., Marciniak, Ł., Schuck, P. J. & Bednarkiewicz, A. Standardization of methodology of light-to-heat conversion efficiency determination for colloidal nanoheaters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 44556–44567 (2021).

Roper, D. K., Ahn, W. & Hoepfner, M. Microscale heat transfer transduced by surface plasmon resonant gold nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111, 3636–3641 (2007).

Chen, J., Ye, Z., Yang, F. & Yin, Y. Plasmonic nanostructures for photothermal conversion. Small Sci. 1, 2000055 (2021).

Gusain, R., Kumar, N. & Ray, S. S. Recent advances in carbon nanomaterial-based adsorbents for water purification. Coord. Chem. Rev. 405, 213111 (2020).

Wang, Y., Meng, H.-M., Song, G., Li, Z. & Zhang, X.-B. Conjugated-polymer-based nanomaterials for photothermal therapy. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2, 4258–4272 (2020).

Xie, Z. et al. The rise of 2D photothermal materials beyond graphene for clean water production. Adv. Sci. 7, 1902236 (2020).

Ahrberg, C. D. et al. Plasmonic heating-based portable digital PCR system. Lab Chip 20, 3560–3568 (2020).

Nabuti, J., Elbab, A. R. F., Abdel-Mawgood, A., Yoshihisa, M. & Shalaby, H. M. Highly efficient photonic PCR system based on plasmonic heating of gold nanofilms. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 14, 100346 (2023).

Son, J. H. et al. Ultrafast photonic PCR. Light Sci. Appl. 4, e280–e280 (2015).

AbdElFatah, T. et al. Nanoplasmonic amplification in microfluidics enables accelerated colorimetric quantification of nucleic acid biomarkers from pathogens. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 922–932 (2023).

Monshat, H., Wu, Z., Pang, J., Zhang, Q. & Lu, M. Integration of plasmonic heating and on-chip temperature sensor for nucleic acid amplification assays. J. Biophotonics 13, e202000060 (2020).

Lim, S. et al. Transparent and stretchable capacitive pressure sensor using selective plasmonic heating-based patterning of silver nanowires. Appl. Surf. Sci. 561, 149989 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. 3D plasmonic nanostructure-based polarized ECL sensor for exosome detection in tumor microenvironment. ACS Sens. 8, 1782–1791 (2023).

Pyrak, E., Kowalczyk, A., Weyher, J. L., Nowicka, A. M. & Kudelski, A. Influence of sandwich- type DNA construction strategy and plasmonic metal on signal generated by SERS DNA sensors. Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 295, 122606 (2023).

Moreira, P. et al. Plasmonic genosensor for detecting hazelnut Cor a 14-encoding gene for food allergen monitoring. Analytica Chim. Acta 1259, 341168 (2023).

Rizalputri, L. N. et al. Preliminary study for the development of a solution phase localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) biosensor based on gold nanoparticle to detect SARS-CoV- 2. AIP Conf. Proc. 2580 (2023).

Qiu, G. et al. Dual-functional plasmonic photothermal biosensors for highly accurate severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 detection. ACS Nano 14, 5268–5277 (2020).

Spitzberg, J. D., Zrehen, A., van Kooten, X. F. & Meller, A. Plasmonic-nanopore biosensors for superior single-molecule detection. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900422 (2019).

Ishii, S., Sugavaneshwar, R. P. & Nagao, T. Titanium nitride nanoparticles as plasmonic solar heat transducers. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 2343–2348 (2016).

Borghei, Y.-S., Hosseinkhani, S. & Ganjali, M. R. “Plasmonic Nanomaterials”: an emerging avenue in biomedical and biomedical engineering opportunities. J. Adv. Res. 39, 61–71 (2022).

Monshat, H. Application of Plasmonic Devices in Spectroscopy and Biomedical Studies. PhD thesis, Iowa State University (2020).

De la Encarnación, C., de Aberasturi, D. J. & Liz-Marzán, L. M. Multifunctional plasmonic- magnetic nanoparticles for bioimaging and hyperthermia. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 189, 114484 (2022).

Lee, S., Sun, Y., Cao, Y. & Kang, S. H. Plasmonic nanostructure-based bioimaging and detection techniques at the single-cell level. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 117, 58–68 (2019).

Donner, J. S. et al. Imaging of plasmonic heating in a living organism. Acs Nano 7, 8666–8672 (2013).

Psarski, M., Lech, A. & Celichowski, G. Plasmonic heating of protected silver nanowires for anti-frosting superhydrophobic coating. Nanotechnology 33, 465205 (2022).

Zhong, H. et al. Plasmonic and superhydrophobic self-decontaminating N95 respirators. ACS nano 14, 8846–8854 (2020).

Qiu, Y. et al. Ultrasensitive plasmonic photothermal immunomagnetic bioassay using real- time and end-point dual-readout. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 377, 133110 (2023).

Quintanilla, M. et al. Thermal monitoring during photothermia: hybrid probes for simultaneous plasmonic heating and near-infrared optical nanothermometry. Theranostics 9, 7298 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. Atomic switches of metallic point contacts by plasmonic heating. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 34 (2019).

Wang, L. et al. Laser-induced plasmonic heating on silver nanoparticles/poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) mats for optimizing SERS detection. J. Raman Spectrosc. 48, 243–250 (2017).

Enders, M., Mukai, S., Uwada, T. & Hashimoto, S. Plasmonic nanofabrication through optical heating. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 6723–6732 (2016).

Fedoruk, M., Meixner, M., Carretero-Palacios, S., Lohmüller, T. & Feldmann, J. Nanolithography by plasmonic heating and optical manipulation of gold nanoparticles. ACS Nano 7, 7648–7653 (2013).

Chiu, C.-S., Chen, H.-Y., Hsiao, C.-F., Lin, M.-H. & Gwo, S. Ultrasensitive surface acoustic wave detection of collective plasmonic heating by close-packed colloidal gold nanoparticles arrays. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 2442–2448 (2013).

Xu, Z., Rao, N., Tang, C.-Y. & Law, W.-C. Seawater desalination by interfacial solar vapor generation method using plasmonic heating nanocomposites. Micromachines 11, 867 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Plasmonic heating from indium nanoparticles on a floating microporous membrane for enhanced solar seawater desalination. Nanoscale 9, 12843–12849 (2017).

Warkentin, C. L., Yu, Z., Sarkar, A. & Frontiera, R. R. Decoding chemical and physical processes driving plasmonic photocatalysis using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopies. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 2457–2466 (2021).

Sarhan, R. M. et al. The importance of plasmonic heating for the plasmon-driven photodimerization of 4-nitrothiophenol. Sci. Rep. 9, 3060 (2019).

Li, F. et al. Plasmonic local heating induced strain modulation for enhanced efficiency and stability of perovskite solar cells. Advanced Energy. Materials 12, 2200186 (2022).

Auer, S. K. Rapid Plasmonic Actuation of Thermoresponsive Hydrogel Structures. PhD thesis, Vienna University of Technology (2022).

Ringe, E. et al. Plasmon length: a universal parameter to describe size effects in gold nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 1479–1483 (2012).

Ringe, E. et al. Correlating the structure and localized surface plasmon resonance of single silver right bipyramids. Nanotechnology 23, 444005 (2012).

Zhu, J. et al. Additive controlled synthesis of gold nanorods (GNRs) for two-photon luminescence imaging of cancer cells. Nanotechnology 21, 285106 (2010).

Ye, X. et al. Seeded growth of monodisperse gold nanorods using bromide-free surfactant mixtures. Nano Lett. 13, 2163–2171 (2013).

Xi, Z. et al. Improving lyophilization and long-term stability of gold nanostars for photothermal applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 17336–17346 (2023).

Guo, Z. et al. Intrinsic optical properties and emerging applications of gold nanostructures. Adv. Mater. 35, 2206700 (2023).

Zhang, H., Zhu, T. & Li, M. Quantitative analysis of the shape effect of thermoplasmonics in gold nanostructures. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 3853–3860 (2023).