Abstract

Parity-time (PT) symmetric resonators have an exact phase with real frequency eigenvalues and a broken phase with complex-conjugate frequency eigenvalues. In the presence of nonlinear gain, the PT-symmetric resonator exhibits nonreciprocal transmission when it is biased at the broken phase, which promises applications for isolators and circulators in modern communication systems. The nonlinear distortion performance is one of the most important metrics in most electronic applications where linearity is critical. This article provides the first experimental results of nonlinear distortion of nonreciprocal transmission in a pair of electrically coupled silicon micromechanical resonators at the broken phase. The results show the 1 dB gain compression point (P1dB) with 5 dBm and the input-referred third-order intercept point (IIP3) with 11.5 dBm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parity-time (PT) symmetric systems featuring balanced gain and loss possess real eigenvalues though they are non-Hermitian1,2. This extends the PT-symmetric systems to a diverse range of physics domains, such as optics and photonics3,4,5, electronics6,7,8, mechanics9, and acoustics10,11. PT symmetry systems exhibit spontaneous phase transitions depending upon the coupling parameters. The system exhibits a pair of complex-conjugate frequency eigenvalues when it is biased at a broken phase where the coupling is weak. One of frequency eigenvalues exhibits the exponential growing mode, while the other displays the exponential decaying mode. The exponential growth mode is unequally suppressed in gain and loss sides owing to the nonlinearity of the gain, resulting in non-reciprocal transmission. This phenomenon has been developed on optical12,13, acoustic14, and electronic15,16,17,18 platforms.

Non-reciprocal components, such as circulators and isolators, facilitate the unidirectional transmission of signals, which are of pivotal importance in modern communication systems. By Lorentz reciprocity theorem, any linear and time-invariant medium with symmetric permittivity and permeability tensors are reciprocal19. Traditional circulators and isolators break time-reversal symmetry, and consequently non-reciprocity, by applying a strong magnetic bias to ferrite cavities. However, they are bulky and incompatible with conventional semiconductor technologies. The aforementioned schemes for non-magnetic non-reciprocal components based on nonlinear PT-symmetric resonators have been explored. The nonlinear distortion induced by a nonlinear gain is critical for most electronic applications. The presence of nonlinearity can distort signals, which can have detrimental effects on signal quality, decrease demodulation accuracy, and negatively impact system stability. However, the nonlinear distortion of the PT-symmetric non-reciprocal system has not been characterized except for LC (inductor-capacitor) resonators17. While numerous studies on micromechanical resonators, including those exploring mode localization20, have delved into nonlinearity analyses, the circumstances differ significantly within the realm of non-Hermitian systems. On the basis of a pair of electrically coupled silicon micromechanical resonators having PT-symmetry21,22, this article presents an experimental measurement for the nonlinear distortion of nonreciprocal transmission in the silicon micromechanical resonators.

Principle of nonreciprocal transmission

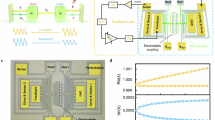

Figure 1a depicts a schematic of PT-symmetric silicon micromechanical resonators. The electrostatic coupling is achieved by applying a DC (direct current) bias across the two resonators. The resonators are placed in a controlled vacuum chamber so that the damping can be adjusted. The feedback loop detects a velocity-dependent signal from the resonator and returns as a force to the resonator, which is equivalent to the gain of the resonator. The signal input and output in both resonator are achieved via capacitance transduction. Figure 1b provides our fabricated silicon micromechanical resonators21,22.

a Schematic of an electrically coupled beam resonators. The electrostatic coupling produces an equivalent coupling spring kc. A feedback loop is used to generate gain gs, and it consists of trans-impedance amplifier (TIA), voltage amplifier (VA), bandpass filter (BPF), automatic gain control (AGC), and phase shifter (PS). Motional current from the gain resonator flows into the feedback loop, and the feedback signal returns to the resonator as a force. Resonator 1 is viewed as a loss resonator, and resonator 2 is viewed as a gain resonator. The forward transmission is defined from the loss resonator to the gain resonator. b Microscope image of fabricated silicon micromechanical resonators. The gold part corresponds to the electrode for feedback, DC supply, and AC path, respectively. The plates in the black dotted frame are electrically coupled

The dynamics of PT symmetry silicon micromechanical resonators is modeled with a coupled spring-mass-damping system. Specifically, the two resonators are identical with mass m and stiffness k with resonance frequency \({\omega }_{0}=\sqrt{k/m}\), however, they exhibit gain cs and loss c, respectively. According to the vibrational mechanics, the frequency eigenvalues are found to be22 (see Methods)

where \(\lambda =\omega /{\omega }_{0}\) is the normalized frequency, \({g}_{s}={c}_{s}/\sqrt{{km}}\) and \(\gamma =c/\sqrt{{km}}\) are the normalized gain and loss. \(\mu ={k}_{c}/k\) is the coupling coefficient, where kc is the coupling spring constant.

Figure 2 depicts the real and imaginary components of the eigenfrequencies according to Eq. (1). There are two distinct phases in silicon micromechanical resonators separated by an exceptional point (EP) at which \(\mu ={\mu }_{{EP}}=({g}_{s}+\gamma )/2\) where the frequency eigenvalues merge. In the exact phase, \(\mu \,>\, {\mu }_{{EP}}\), where the real part of the two eigenfrequencies are different. While in the broken phase, \(\mu \,<\, {\mu }_{{EP}}\), the eigenfrequencies are complex conjugate pairs. When the system is operated at broken phase, the exponential growth eigenstate is suppressed by nonlinear gain, resulting in non-reciprocal transmission while the identical real parts correspond to the single transmission peak.

The non-reciprocal ratio is defined as the amplitude ratio of the forward to backward transmission. It is given by22 (see the Supplementary materials for details)

where gf is the gain of forward transmission and gb is the gain of backward transmission, respectively. It can be seen that the non-reciprocal ratio depends upon the nonlinear gain of the forward and backward transmission, which would result in nonlinear distortion. Here, forward transmission is defined as from the loss resonator to the gain resonator. The behavior of the gain and loss resonator is contingent upon the amplitude of the signal traversing them. Generally, more potent signals experience increased attenuation due to the nonlinear gain. Signals from the gain side encounter the nonlinear gain region at higher amplitudes, leading to greater attenuation. Conversely, signals from the loss side enter the nonlinear region at reduced amplitudes and thus undergo less attenuation.

Experiments and results

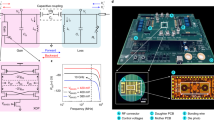

Using the equivalent lumped circuit representation of PT-symmetric micromechanical resonators, we simulated and optimized the non-reciprocal transmission by Simulation Program with Integrated Circuits Emphasis (SPICE) (see the Supplementary materials for details). After optimization, a pair of electrostatically coupled micromechanical resonators were fabricated on an n-type (100) silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafer, as shown in Fig. 1b. Parameters of the resonators are given in the Supplementary materials. Parameters of the resonators are given in the Supplementary materials. The micromechanical resonators were fixed on a printed circuit board (PCB) and bonded to the golden pad on the PCB to establish an electrical connection. The PCB attached to the resonators was placed in a vacuum chamber equipped with a controlled vacuum gauge to stabilize the damping. The resonators were driven and sensed by capacitive transduction. The realization of the nonlinear gain is described in detail in the Supplementary material. Zurich HF2LI lock-in amplifier supports the driving signal and detects the output signal from the resonators. Each point was sampled 20 times and then averaged to improve the accuracy of the measurement.

To characterize the nonlinear distortion of nonreciprocal transmission, the gain factor g was initially set to be less than γ to ensure that the resonators did not undergo self-sustained oscillation in the absence of external driving signals. The system was operated at the broken PT-symmetric phase, i.e. \(\mu \,<\, (g+\gamma )/2\). Accordingly, the PT-symmetric resonators were operated under forced oscillation. As the amplitude of the external driving signals increases, the nonlinear gain gs instead of g will take effect. The optimized parameters are as follows22: \(\mu =4.3\times {10}^{-4}\)(corresponding to the DC bias voltage of 5 V, see Supplementary materials S10), \(\gamma=1.2\times {10}^{-3}\), \(g=0.6\times {10}^{-3}\) and the input signal vpp = 15 mV. The non-reciprocal ratio as a function of frequency from 107.026 kHz to 107.066 kHz is shown in Fig. 3a. It was demonstrated that the optimal operating frequency for non-reciprocal transmission is 107.046 kHz. Figure 3b plots the insertion loss and isolation as a function of frequency. The insertion loss and isolation at 107.046 kHz are about 10 dB and 18 dB, respectively. The FWHM (full-width at half-maximum bandwidth) is about 7 Hz, indicating a high-quality factor (Q = 15300).

a Simulated (black square) and measured (yellow circle) non-reciprocal ratio as a function of frequency. b Measured Insertion loss (yellow square) and isolation (blue circle) as a function of frequency. Experimentally, μ = 4.3 × 10−4, γ = 1.2 × 10−3, and input signal amplitude vpp = 15 mV. The DC bias voltage across the two resonators was set to be 5V

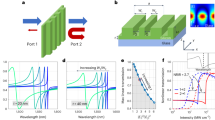

The 1 dB gain compression point (P1dB) was measured with the resonators driven by a sinusoidal signal at the frequency of 107.046 kHz. The input level was from −6.5 dBm to 16 dBm. The input level refers to the input amplitude expressed in dBm, which makes the characterization of nonlinear trends more visualized. As shown in Fig. 4, due to the phenomenon of gain compression, the measured output is offset from the linear output. The P1dB is defined as the input level at which the gain experiences a 1-decibel reduction relative to the linear gain23. When the input level is <0 dBm, the curve is nearly linear, allowing for the linear fitting. The measured P1dB is approximately at the input level of 5 dBm. The simulation results, which is ~6 dBm, are compared with the experimental results. The difference between the simulation and experimental results may be attributed to the electrostatic nonlinearity from capacitance transduction24,25 and the spring softening effect owing to the nonlinearity of the resonator stiffness26,27. Thus, the simulation model including both the electrostatic nonlinearity and geometric nonlinearity is further needed.

The performance of intermodulation distortion is evaluated in terms of the IIP3 parameter. A dual-frequency sinusoidal signal is utilized as a driving signal during simulations and experiments to generate the third-order intermodulation component (IM3). The frequencies of the dual-frequency driving signal are 107.043 kHz and 107.049 kHz, respectively, which deviate by 3 Hz from the central frequency to ensure that the signal is completely within the resonator passband. For a dual-frequency input signal with the same amplitude, the output amplitude at fundamental frequency and IM3 exhibit linear and cubic relations with the input amplitude, respectively. The intersection point of these two lines in logarithmic coordinates is defined as IIP323. Figure 5a, b display the FFT (fast Fourier transform) spectrum. Only fundamental components are observed at \(\varDelta f=\pm 3\) Hz for an input level of −3 dBm. As the input level increases, intermodulation components will appear. For instance, at an input level of 4.5 dBm, an obvious intermodulation component occurs at \(\varDelta f=\pm 9\) Hz, which corresponds to the IM3.

Figure 6 plots the simulation and experimental IIP3 under the driven signal of a dual-frequency input (107.043 kHz and 107.049 kHz) for input levels from −6.5 dBm to 13 dBm. The experimental IIP3 is found at the input level of about 11.5 dBm, which is lower than that of simulation (16.5 dBm). Compared to the simulation results, the IM3 appears at an early stage in the experiments. During the simulation, IM3 is only due to the nonlinearity of the gain, as the RLC model used in the simulation is linear. Whereas in addition to the nonlinear gain, the electrostatic nonlinearity from capacitance transduction25,26 and the spring softening effect owing to the nonlinearity of the resonator stiffness26,27 obviously amplify the IM3 in the experiments. Thus, a simulation model that further incorporates both the electrostatic nonlinearity and geometric nonlinearity is required.

The device is driven with a dual-frequency (107.043 kHz and 107.049 kHz) signal. The yellow square and blue circle correspond to the experimental results at fundamental frequency and IM3. The black lines with triangle and rhombus are the simulated results at fundamental frequency and IM3. The dash line are the fitting results, the intersection of which determines IIP3 in simulation and experiment

Conclusions

In conclusion, the nonlinear distortion of the non-reciprocal transmission in broken PT-symmetric silicon micromechanical resonators has been studied by simulations and measurements. Experiments show that the P1dB is found at input level of 5 dBm, while the IIP3 is measured at input level of 11.5 dBm. The performance of non-reciprocal transmission is theoretically attributed to nonlinear gain. In practice, however, the nonlinear driving and stiffness of silicon micromechanical resonators further exacerbate the nonlinear distortion. Our simulation and experimental findings offer valuable guidance to performance optimization of PT-symmetric silicon micromechanical resonators for non-reciprocal devices such as circulators and isolators.

Methods

Dynamics of PT-symmetric micromechanical resonators

According to the Newtown’s Law, the system dynamics are descried by

where m and k are the mass and spring constant of single resonator, c and cs are the damping coefficient of the loss and gain resonator, kc is the coupling spring constant, xL and xG are the vibration displacement of the loss and gain resonator, respectively.

Taking \({x}_{L,G}={a}_{L,G}{e}^{{\rm{i}}\omega t}={a}_{L,G}{e}^{{\rm{i}}\lambda \tau }\) where aL and aG are the respective displacement amplitude of the loss and gain resonator, Eq. (3) is rewritten as

where \(\lambda =\omega /{\omega }_{0}\) is the normalized angular frequency, ω is the operation angular frequency, \(\tau ={\omega }_{0}t\) is the normalized time, \({g}_{s}={c}_{s}/\sqrt{{km}}\) and \(\gamma =c/\sqrt{{km}}\) are the normalized gain and loss, and \(\mu ={k}_{c}/k\) is the coupling coefficient, respectively.

Using an approximation that \(\gamma \lambda \approx \gamma\), \({g}_{s}\lambda \approx {g}_{s}\) and \({\lambda }^{2}\approx 2\lambda -1\), Eq. (4) is simplified as

Solving Eq. (5) leads to Eq. (1).

Measurement of P1dB and IIP3

In nonlinear circuits, the gain of output signal \({v}_{{out}}\left(t\right)\) depends on the input level of input signal \({v}_{{in}}\left(t\right)\). It may be expressed in the form of a power series,

where gn are the real-valued coefficients.

When the input signal is a single-frequency sinusoidal signal

where A is the amplitude of the input signal, and according to Eq. (6), a general third-order nonlinear transmission characteristic is given by

In general, g3 is negative, meaning that the gain is compressive. It is usually characterized by the power output at 1 dB gain compression, P1dB, which is given by23

where Pl is the output power in dB at the low input power levels where the circuit is linearly operated, Pnl is the output power in dB at the high input power levels. Pl at the high input power levels can be extrapolated using those at the low input power levels.

When the input signal is a dual-frequency sinusoidal signal,

a general third-order nonlinear transmission characteristic is given by, according to Eq. (6),

with

Obviously, as the input power increases, the output power of the 3rd-order intermodulation grows as the cube of input power, resulting in intermodulation distortion. The intermodulation distortion is usually characterized by the output-referred third-order intercept point, IIP3, which is given by23

where Pbf is the output power of the fundamental signal, PIM3 is the output power of the intermodulation signal, and G is the amplification factor of the fundamental signal.

During measurements, the amplitude of the driven signal from −6.5 dBm to 16 dBm was pumped sequentially with a 27 V DC bias superimposed on the electrode for P1dB. A dual-frequency driving signal was obtained by synthesizing sinusoidal signals from two independent oscillators of a lock-in amplifier. The dual-frequency signal was then pumped into the device causing nonlinear distortion. The output signal containing both the fundamental frequency component and intermodulation component was acquired through the spectrum analysis module of the lock-in amplifier.

Fabrication of silicon micromechanical resonators

The device was produced on SOI wafer with two-step lithography. The first lithographic process defines the pattern of the metal electrode, while the second lithographic process defines the pattern of the resonator. The lithographic pattern is transferred to the device layer via deep reactive ion etching (DRIE). Once the oxide layer had been etched, the resonant beam and the movable electrode were released. Fig. S3 in Supplementary material outlines the fabrication process. The resonant beam and movable electrode are both 8 μm in width and 25 μm in depth, but with 500 μm and 260 μm in length, respectively.

Measurement set-up

The fabricated device was mounted on an adapter plate. A connection is created between the adapter plate and the device electrode through the process of wire bonding. The adapter plate is positioned within the vacuum chamber, and the vacuum degree is set at 2.7 torr. The DC bias required for devices and active circuits is provided by the RIGOL DP800 voltage source. The experimental signals were collected by Zurich HF2LI lock-in amplifier and were averaged on the basis of 20 individual samples. An HF2TA is installed in front of the signal acquisition terminal with the function of converting the current signal. The experimental setup is specifically defined in Supplementary Fig. S6.

Measurement set-up of non-reciprocal ratio

A voltage signal with an amplitude of 15 mV was directly pumped into the device to drive the resonators. The amplitude and frequency information of the output signal is obtained through the frequency sweep analysis module of lock-in amplifier.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bender, C. M. & Boettcher, S. Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5243–5246 (1998).

Bender, C. M., Brody, D. C. & Jones, H. F. Complex extension of quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 270401 (2002).

Chen, W., Ozdemir, S. K., Zhao, G., Wiersig, J. & Yang, L. Exceptional points enhance sensing in an optical microcavity. Nature 548, 192 (2017).

Rueter, C. E. et al. Observation of parity-time symmetry in optics. Nat. Phys. 6, 192 (2010).

Ozdemir, S. K., Rotter, S., Nori, F. & Yang, L. Parity-time symmetry and exceptional points in photonics. Nat. Mater. 18, 783 (2019).

Schindler, J. et al. PT-symmetric electronics. J. Phys. A 45, 444029 (2012).

Schindler, J., Li, A., Zheng, M. C., Ellis, F. M. & Kottos, T. Experimental study of active LRC circuits with PT symmetries. Phys. Rev. A 84, 040101 (2011).

Bittner, S. et al. PT symmetry and spontaneous symmetry breaking in a microwave billiard. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 024101 (2012).

Bender, C. M., Berntson, B. K., Parker, D. & Samuel, E. Observation of PT phase transition in a simple mechanical system. Am. J. Phys. 81, 173 (2013).

Zhu, X., Ramezani, H., Shi, C., Zhu, J. & Zhang, X. PT-symmetric acoustics. Phys. Rev. X 4, 031042 (2014).

Fleury, R., Sounas, D. & Alu, A. An invisible acoustic sensor based on parity-time symmetry. Nat. Commun. 6, 5905 (2015).

Peng, B. et al. Parity-time-symmetric whispering-gallery microcavities. Nat. Phys. 10, 394 (2014).

Chang, L. et al. Parity-time symmetry and variable optical isolation in active-passive-coupled microresonators. Nat. Photon. 8, 524 (2014).

Shao, L. et al. Non-reciprocal transmission of microwave acoustic waves in nonlinear parity-time symmetric resonators. Nat. Electron. 3, 267 (2020).

Cao, W. et al. Fully integrated parity-time-symmetric electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 262 (2022).

Zhou, Y., Wang, H.-Y., Wang, L.-F., Dong, L. & Huang, Q.-A. Non-reciprocal transmission of coupled LC resonators through parity-time symmetry breaking. J. Phys. Commun. 7, 065003 (2023).

Zhou, Y., Wang, H.-Y., Wang, L.-F., Dong, L. & Huang, Q.-A. Experimental study of the nonlinear distortion of non-reciprocal transmission in nonlinear parity-time symmetric LC< resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 233301 (2023).

Dong, L., Chen, D.-Y., Zhou, Y. & Huang, Q.-A. Noise performance analysis of PT-symmetric non-reciprocal transmission systems. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 063507 (2024).

Nagulu, A., Reiskarimian, N. & Krishnaswamy, H. Non-reciprocal electronics based on temporal modulation. Nat. Electron. 3, 241 (2020).

Thiruvenkatanathan, P., Yan, J., Woodhouse, J. & Seshia, A. A. Enhancing parametric sensitivity in electrically coupled MEMS resonators. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 18, 1077–1086 (2009).

Zhang, M.-N., Dong, L., Wang, L.-F. & Huang, Q.-A. Exceptional points enhance sensing in silicon micromechanical resonators. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 12 (2024).

Wang, R., Han, L., Zhang, M.-N., Wang, L.-F. & Huang, Q.-A. Nonreciprocal transmission in silicon micromechanical resonators via parity-time symmetry breaking. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 034060 (2024).

Darabi, H. J. C. U. P. Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits and Systems 1st ed, Vol. 474 (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Elshurafa, A. M. et al. Nonlinear dynamics of spring softening and hardening in folded-MEMS comb drive resonators. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 20, 943 (2011).

Wang, K. et al. A decouple-decomposition noise analysis model for closed-loop mode-localized tilt sensors. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 157 (2023).

Kaajakari, V., Mattila, T., Oja, A. & Seppä, H. Nonlinear limits for single-crystal silicon microresonators. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 13, 715 (2004).

Zhang, H. M. et al. Mode-localized accelerometer in the nonlinear duffing regime with 75 ng bias instability and 95 ng/√Hz noise floor. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 17 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 61727812, 62074032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.A.H. and L.H. conceived the idea and planned the research. R.W. performed the simulations and experiments. M.N.Z. and L.F.W. fabricated the samples. R.W. and L.H. wrote the paper. Q.A.H. revised the paper with input from all the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, R., Han, L., Zhang, MN. et al. Nonlinear distortion of nonreciprocal transmission in parity-time-symmetric silicon micromechanical resonators. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 99 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-00952-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-00952-0

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced sensitivity in nonlinear parity-time symmetric silicon micromechanical resonators

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2026)