Abstract

Thermal scanning probe lithography (t-SPL) is a high-resolution nanopatterning technique that employs a heated probe for precise, maskless patterning. Polypropylene carbonate (PPC) has emerged as a promising resist material for t-SPL due to its favorable thermal decomposition behavior. In this study, we investigate the use of PPC as a thermal resist in t-SPL, leveraging its chain unzipping and random scission mechanisms to achieve controlled material removal. The effects of various parameters on the patterning of PPC films, such as temperature, tip height, and force pulse, are systematically examined. Upon exposure to the heated tip, PPC undergoes localized sublimation at the contact area, enabling nanopatterning with the lateral resolution down to 50 nm and the vertical resolution down to sub-nanometer. This approach achieves stepped cyclic and sinusoidal grayscale patterns with controllable depth and size. Furthermore, we demonstrate grayscale pattern transfer by etching the PPC patterns into dielectric layers using optimized dry etching processes. This approach offers precise depth control and shows strong potential for applications in photonic and nano-electronic device fabrication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a fundamental technology in the semiconductor and integrated circuit industries, lithography has continuously evolved with advancing technology nodes. Beyond extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography, various high-resolution micro-/nanofabrication techniques have emerged, including electron beam lithography (EBL)1 and scanning probe lithography (SPL)2. Among them, thermal scanning probe lithography (t-SPL), with its mask-free patterning, high resolution, and low environmental dependence, has emerged as a key technique for overcoming the optical diffraction limit in the fabrication of nano-electronic devices and photonic chips3. As a specialized form of SPL, this technique leverages the localized heating effect of an ultrafine probe tip4, which transfers thermal energy to the thermosensitive resist, causing rapid decomposition and evaporation within a short timescale. By precisely controlling the probe’s movement, high-resolution custom patterns can be directly inscribed onto the resist surface5, enabling scalable manufacturing as well6. Currently, this method has been successfully applied to various nanofabrication fields, including grayscale lithography7,8, high-precision nanostructure fabrication9,10,11, low dimensional material patterning12,13, and device manufacturing14,15,16.

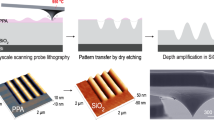

The integration of grayscale lithography with t-SPL advances nanofabrication capabilities by enabling precise depth control in complex nanostructures, significantly broadening the technique’s versatility for gradient-topography applications. As one of the advanced techniques derived from t-SPL technology, grayscale lithography allows for producing 2.5D structures with precise depth control and emerges as a key technique for advancing micro- and nanodevices like microelectromechanical systems17 and diffractive optical elements18. For instance, in nanofluidic devices, it facilitates the separation of nanoparticles with diameter variations as small as 1 nm17. In optics, grayscale gratings offer enhanced control over diffraction wavefronts, enabling the creation of both periodic and aperiodic surface patterns with continuous depth modulation and subwavelength spatial resolution19. Additionally, grayscale pattern transfer is applied in nano-device fabrication20, enabling precise control of high aspect ratio patterns. Grayscale pattern transfer technology combines grayscale patterning with subsequent etching transfer processes, utilizing optimized etching parameters and cooling cycles to achieve significant transfer of patterns. This approach relies on precise control of thermal effects and etching processes, enhancing both the depth and resolution of the patterns21. Using this method, sub-nanometer grayscale patterning has been successfully achieved, with depth amplification reaching < 100 nm and 5 times into SiO2 without shape distortion8. The grayscale nano-patterning lithography technology drives advancements in nanotechnology and microsystems.

The effectiveness of t-SPL technology relies on thermosensitive materials with high thermal responsiveness and low decomposition activation energy. The most commonly used material is polyphthalaldehyde (PPA)22, alongside alternatives such as poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), and silk fibroin (SF)23. In particular, PPC is a polymer synthesized via the copolymerization of propylene oxide and carbon dioxide24,25. It exhibits excellent transparency, flexibility, and mechanical strength, along with desirable properties such as thermal degradability, biodegradability, and chemical stability24,26,27,28. Especially, the pyrolysis characteristics of PPC have been widely studied, and many experiments have demonstrated from multiple directions that PPC has the property of decomposition and sublimation at high temperatures28,29,30,31,32. These characteristics make PPC an attractive intermediate material in micro-/nanofabrication processes.

In this study, we demonstrated high-resolution patterning on PPC films using t-SPL and employed the patterned PPC layer as a sacrificial film to transfer grayscale nanopatterns into a dielectric layer. We systematically investigated the effects of tip temperature and force (modulated by tip height and force pulse) on patterning precision, achieving a minimum feature size of 50 nm. Additionally, sinusoidal wave patterns with tunable sizes/depths and stepped cyclic grayscale patterns were successfully fabricated on PPC films. Furthermore, combining grayscale nanopatterns with reactive ion etching (RIE) enabled precise pattern transfer into a silicon dioxide dielectric layer. These results highlight the significant potential of PPC as a thermosensitive resist for high-resolution, efficient, and compatible nanomanufacturing.

Results and discussion

Thermal decomposition properties of PPC

PPC is a biodegradable and eco-friendly aliphatic polycarbonate polymer synthesized from carbon dioxide (CO₂) and propylene oxide (PO)25, offering great potential for sustainable material applications. The material’s performance, particularly in high-temperature environments, is closely linked to its thermal stability. Several factors influence the thermal decomposition behavior of PPC, including molecular weight, heating rate, and the presence of catalysts or end-capping agents30. Understanding its thermal decomposition mechanisms is essential for improving the polymer’s thermal durability and broadening its application scope.

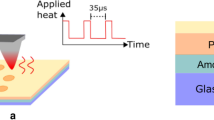

To explore the thermal response of PPC under localized heating, patterning of the PPC films is performed by a thermal scanning probe, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The probe operates over a wide range of temperature from 90 °C−1350 °C, enabling precise thermal modulation of the polymer surface. Figure 1a demonstrates the ability of the heated tip to generate grayscale surface patterns, with the corresponding cross-sectional profile indicating controlled depth variation. The chemical structural formula of PPC is shown in Fig. 1b. Its molecular linkage structure is closely associated with its thermal decomposition behavior. Upon contact with the heated probe, PPC undergoes thermal degradation and primarily via two pathways: chain unzipping and random chain scission29,31, which dictate the decomposition temperature, thermal stability, and byproducts. Figure 1c shows the SEM image of the thermal tip, with the entire tip length measuring approximately 730 nm and the tip diameter ranging from 10 to 20 nm. Tip wear and contamination of the tip during the patterning process may negatively affect its geometry and patterning quality. A detailed analysis is provided in Fig. S1.

a Schematic diagram of PPC patterning using a thermal tip. b Chemical structure of Polypropylene carbonate (PPC). c An SEM image of the thermal tip. d Schematic representation of two thermal decomposition pathways of PPC. The blue wavy line indicates chain unzipping, leading to the formation of cyclic propylene carbonate, while the red wavy line depicts random chain scission via thermal cleavage of C–O bonds, generating CO2 and other gaseous byproducts

The PPC polymer chain consists of alternating carbonate linkages and propylene segments. The carbonate linkages, formed through the incorporation of CO2, impart rigidity, stability, and biodegradability to the material. Despite their relatively high bond energy, these linkages are prone to cleavage at elevated temperatures, serving as the primary decomposition sites. In contrast, the propylene segments, formed by ring-opening polymerization of propylene oxide, provide good flexibility and processability. Figure 1d and Fig. S2 show the thermal decomposition pathways of PPC chains. The blue wavy line presents the chain unzipping via the backbiting mechanism involving alkoxide or carbonate groups, yielding cyclic propylene carbonate and propylene glycol. The red wavy line indicates random chain scission induced by thermal cleavage of C–O bonds, producing CO2 and other gaseous byproducts29,31. In addition, the methyl groups on the side chains may facilitate side-chain scission during thermal degradation.

The onset decomposition temperature of PPC typically ranges from 150 °C to 200 °C influenced by its molecular weight and residual catalyst content. Higher molecular weight PPC exhibits slightly enhanced thermal stability due to increased chain entanglement, while lower molecular weight PPC decomposes more readily. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)29,32 reveals that the maximum decomposition rate occurs between 250 °C and 300 °C, with nearly complete decomposition observed above 300 °C. During the thermal decomposition, cleavage of carbonate linkages results in CO₂ release and the formation of ether-containing oligomers or small molecules. In parallel, degradation of the propylene segments leads to the formation of volatile products such as propylene and propane. Under high-temperature pyrolysis, nearly all decomposition products sublime directly into a gaseous form.

Based on the principle of thermal decomposition of PPC, when the temperature in a highly localized region exceeds its pyrolysis threshold, the polymer undergoes rapid thermal decomposition and sublimation upon exposure to the heated tip. This thermally responsive characteristic establishes the fundamental basis for direct-write micro-/nanopatterning through spatially confined pyrolysis. In combination with t-SPL technology, once the cantilever temperature surpasses the decomposition threshold of PPC, the material at the point of contact is expected to sublimate instantly, resulting in localized material removal. This allows for precise patterning on the surface of the PPC film, making it a promising material for high-resolution thermal lithography.

The t-SPL patterning of PPC

Due to the pyrolysis characteristics of PPC and the direct sublimation of its pyrolysis products, micro-/nanopatterning can be readily achieved using a heated scanning probe. During patterning, the cantilever deflects downward to bring the thermal tip into contact with the sample surface. As illustrated in Fig. 2a, various parameters affect the patterning performance of the thermal tip. Here, T (°C) denotes the tip temperature, and the tip height refers to the vertical distance between the tip and the PPC film surface. During t-SPL patterning, the cantilever deflection can occur through two mechanisms: thermally induced bending and electrostatic actuation by applying a voltage between the tip and the substrate.

a Schematic diagram illustrating the principle of tip patterning on a PPC film. Both temperature and applied voltage contribute to the downward bending of the cantilever simultaneously. b The line patterns generated at different tip temperatures ranging from 200 °C to 1300 °C (Tip height is 250 nm, Force pulse is 5 μs). c Depth profile of the patterns in (b) along the arrow. The target depth of 30 nm is achieved when the tip temperature exceeds 950 °C. d Line patterns formed with varying force pulse from 1 μs to 10 μs (Tip height is 250 nm, Temperature is 1050 °C). e Depth profile of the patterns in d along the arrow, showing that the stable patterning occurs when the force pulse exceeds 4 μs. f Line patterns formed with different tip heights ranging from 310 nm to 170 nm (Temperature is 1050 °C, Force pulse is 5 μs). g Corresponding depth profile of (f) along the arrow, indicating that the optimal depth is reached when the tip height is below 250 nm

Among these parameters, the tip writing temperature is the most critical factor that directly determines the patterning resolution and depth. As shown in Fig. 2b, c, when the target engraving depth is set at 30 nm, the morphology of the line-shaped features varies with the tip temperature ranging from 200 °C to 1300 °C. The target depth is achieved when the temperature exceeds 950 °C, significantly higher than the decomposition temperature of bulk PPC. This discrepancy is attributed to the low efficiency of heat transfer into the PPC film due to the short contact time. Although the tip temperature increases monotonically with heater temperature, accurate quantification remains challenging due to the high and poorly defined thermal resistance of the tip13. Previous studies indicate that the actual temperature at the tip-sample interface is approximately 40% of the heater temperature33,34.

The force pulse refers to the duration of the voltage applied to the tip, which causes the tip to bend downward and contact the sample surface for patterning. However, due to the mechanical response time of the tip, the actual contact time with the sample is shorter than the applied voltage duration. When we keep other parameters unchanged, we further investigated how the force pulse influences the patterning performance. The applied force is generated by the voltage applied between the tip and the substrate, and the force pulse refers to the duration of the applied voltage, which induces the cantilever bending. As shown in Figs. 2d, e, and S3, we maintain a constant applied voltage, when the pulse duration is insufficient, the contact time between the tip and the substrate is too short, making it difficult to form patterns. In our case, stable depth patterns on PPC could only be achieved when the pulse duration exceeded 4 μs.

Another factor that affects the patterning effect is tip height. Reducing the tip height increases the tip-sample proximity, thereby enabling deeper pattern formation under cantilever deflection. As shown in Fig. 2f, g, optimal patterning depth is achieved when the tip height is maintained below 250 nm. It is worth noting that during single-parameter investigations, all other parameters remain appropriate and unchanged.

The protrusions at the sidewalls in Fig. 2c, e, and g likely result from lateral thermal diffusion, tip-induced deformation, and material accumulation during patterning. Local heat spread may cause partial PPC decomposition beyond the intended region, while mechanical interaction and insufficient heating can lead to flow or residue pileup near the edges.

To further investigate the relationship between temperature and engraving depth, we introduced a temperature map, as shown in Fig. 3a. Each grid in the map represents a specific temperature, uniformly ranging from 600 °C to 1200°C. During the patterning process, all other parameters were kept constant, with only the tip temperature varied. As shown in Fig. 3b, increasing the temperature resulted in progressively deeper engraving, as confirmed by AFM measurements. At 600 °C, the probe was unable to pattern the PPC film, whereas at temperatures over 1050 °C, the engraving depth exceeded 100 nm while maintaining low surface roughness. Surface roughness was quantified via the arithmetic mean roughness (Ra), computed from flattened AFM height images. Ra is the arithmetic average of the absolute deviations of surface height points from the mean plane within a defined analysis area. Figure 3c shows the AFM image of the surface roughness in the patterned region from Fig. 3b, with a measured surface roughness Ra of ~0.29 nm. The precise depth control at sub-nanometer scale demonstrated the high vertical resolution capability of t-SPL.

a Temperature map of a patterned area, with each grid uniformly increasing from 600 °C to 1200 °C. b Corresponding AFM image of the patterned area, where each grid exhibits a distinct patterning depth correlated with the local temperature in the map. c 3D morphology AFM image of b and a selected representative area showing the surface topography and roughness (Ra). d High-resolution line array engraved by the scanning thermal probe on the PPC sample. e AFM depth profile of the line array shown in d, with the blue line indicating the scanning path. The minimum line width (also called by half-pitch) is approximately 50 nm. f High-resolution letter pattern engraved with t-SPL, with a line width of <100 nm

By positioning the probe 200 nm above the sample surface and applying increased probe force while maintaining a controlled temperature of 950 °C, we achieved extremely high-resolution patterning, as demonstrated in Fig. 3d. The patterns were generated through simultaneous patterning (writing) and scanning (reading) by using the same probe, achieving a minimum line width of approximately 50 nm. This resolution is influenced not only by the surface properties of the material, but also critically by the tip diameter, typically ranging from 10 to 20 nm. The geometry of the tip determines the relationship between patterning depth and minimum resolution35, as detailed in Fig. S4. Figure 3e displays the depth profile of the pattern in Fig. 3d, obtained using the probe’s reading mode, confirming a minimum feature size of 50 nm based on the half-pitch measurement. Demonstrating the capability for customized, fine-scale patterning, Fig. 3f presents letter patterns engraving on the PPC film at the minimum achievable resolution. The minimum letter line width remains <100 nm, highlighting the precision of the technique. We also examined the minimum patterning resolution of several commonly used thermosensitive resists for t-SPL, as presented in Fig. S5.

Basically, t-SPL enables high-precision patterning on PPC surfaces with a minimum feature size of 50 nm, making it well-suited for nanoscale device fabrication. Precise modulation of both temperature and applied force enables controlled material removal and tailored surface morphology, providing distinct advantages for micro-nano fabrication processes.

Grayscale-structured surfaces with nanoscale architectures are increasingly used in diverse fields, particularly in optical systems19 and microfluidic manipulation17. Grayscale patterns encode height, thickness, or depth information through continuously varying pixel intensities, enabling precise 3D structuring in micro-/nanofabrications7,8,20,36,37. Such patterns are widely used in lithography, etching, and thermal probe processing to control material removal or deposition. Grayscale nanopattern transfer enhances both resolution and fabrication depth, facilitating the creation of high-precision 3D micro/nanostructures.

Previous studies have demonstrated grayscale pattern amplification using PPA-based materials8,21. Given its thermal sensitivity similar to that of PPA, we investigated whether PPC can also be used to combine t-SPL grayscale patterning and RIE dry etching for pattern transfer into dielectric layers. We first explored the ability to directly engrave grayscale nanopatterns on the surface of PPC films. As shown in Fig. 4a, t-SPL precisely generated a sinusoidal grayscale pattern with alternating light and dark regions, which was scanned using the probe’s reading mode. The corresponding grayscale images are shown in Fig. S6. The brightest areas correspond to an engraving depth of zero (the sample surface), while the darkest areas indicate the maximum engraving depth. Figure 4b presents a 3D reconstruction of the engraved sinusoidal grayscale pattern in Fig. 4a, with a peak-to-peak distance of 2 μm and a maximum engraving depth reaching over 55 nm. The corresponding depth profile, shown in Fig. 4c and measured along the red line in Fig. 4a, compares the target depth profile (red) with the actual measured depth (blue). The close match between the two curves confirms that t-SPL enables high-precision grayscale patterning on PPC thin films.

a AFM top view of a sinusoidal grayscale pattern engraved by t-SPL on the PPC surface. b 3D structure of the sinusoidal grayscale pattern. c Depth profile measured along the red line in a. The red line in c represents the target depth, while the blue line represents the actual patterned depth of the PPC pattern. d Stepped cyclic grayscale pattern, with each grayscale level corresponding to a different patterning depth. e Depth profile measured along the patterning direction of the stepped grayscale pattern (blue line) in d

To further evaluate the capability, we examined patterns with varying sizes and writing depths, as shown in Figs. S7–S8. The finest patterning resolution achieved was a sinusoidal pattern with a 0.2 μm period. The maximum stable grayscale depth was 120 nm; beyond this depth, deformation was observed. At a depth of 150 nm, the sinusoidal pattern became distorted, indicating the practical limit of grayscale patterning on the PPC films using the thermal probe.

In addition to the sinusoidal-shaped patterns with continuous depth variation, stepped grayscale structures at discrete depths were also achieved, as shown in Fig. 4d and S9. Each grayscale level corresponds to a specific t-SPL patterning depth. The circular staircase pattern demonstrates the technique’s capability for customized depth modulation within the probe’s effective operating range. The corresponding height profle along the stepped grayscale pattern is presented in Fig. 4e.

Grayscale dry etching of PPC

Next, we demonstrate grayscale pattern transfer by combining t-SPL and reactive ion etching (RIE). The fabrication process flow is shown in Fig. 5a. A PPC solution was spin coated onto a Si/SiO2 substrate to form a uniform polymer film. A pre-defined sinusoidal grayscale pattern was directly written onto the PPC surface using a t-SPL probe, leveraging its sub-nanometer depth control. After engraving the grayscale pattern, it was transferred into the underlying dielectric SiO2 layer through RIE. A uniform set of etching parameters was used to simultaneously etch both the PPC layer and the underlying SiO2. As a result, the sinusoidal pattern in the PPC was proportionally reduced in depth during transfer to the SiO2 layer. During the etching process, the valleys of the sinusoidal PPC pattern exposed the SiO2 surface. Due to the etching selectivity between PPC and SiO2 when using a CHF₃/Ar gas mixture, differential etching rates occurred. Once the PPC layer was fully etched away, a sinusoidal grayscale topography was replicated on the SiO2 surface. The detailed procedure is provided in Figs. S10–S11, and the corresponding etch rate is summarized in Fig. 5b.

a Schematic side view of the process flow for transferring the sinusoidal grayscale pattern from PPC to the SiO2 layer. 1) A 6.5 wt% PPC solution is spin-coated onto a Si/SiO₂ substrate to form a uniform film. 2) A sinusoidal grayscale pattern is engraved on the PPC surface using t-SPL. 3) The grayscale pattern is transferred to the underlying dielectric SiO₂ layer via reactive ion etching (RIE). 4) RIE continues until the entire PPC layer is etched away and the pattern is fully transferred into the SiO₂ substrate. b Etching rate of PPC and SiO2 under different RF powers during RIE. Under identical conditions, the etching rate ratio is approximately 7:4. c AFM image and corresponding height profile along the white arrow after grayscale pattern transfer. d Demonstration of pattern transfer beyond sinusoidal structure, using circular ring patterns as an example. e SEM image of the transferred ring pattern shown in d

Figure 5c presents the AFM morphology and corresponding height profile of the SiO2 layer after pattern transfer. The profile shows a clear correspondence to the original PPC sinusoidal pattern. For example, a sinusoidal pattern with a depth of 120 nm was patterned on the PPC layer, and after RIE, a sinusoidal structure with a peak depth of ~68 nm was obtained on the SiO₂ surface. The etching rate ratio between PPC and SiO₂ was calculated to be approximately 7:4. Meanwhile, the dry etching process effectively preserves the morphology and fidelity of the original grayscale pattern, as shown in Fig. S12. These results confirm that grayscale patterns engraved on PPC films via t-SPL can be proportionally transferred into dielectric materials with high fidelity, enabling the fabrication of complex nanoscale 3D surface structures.

In addition to amplifying grayscale patterns, PPC also enables arbitrary pattern etching amplification, leveraging t-SPL’s fast and customizable engraving capabilities. For instance, circular patterns can be transferred from the PPC layer to the substrate oxide layer through t-SPL patterning followed by RIE etching. The AFM and SEM images of the resulting structures are shown in Fig. 5d, e, with the corresponding depth profile and additional details provided in Fig. S13. Overall, PPC-based grayscale pattern transfer offers high precision and multi-level depth control, facilitating the fabrication of complex 3D templates and functional micro/nano devices.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study presents a comprehensive investigation of PPC as a resist material for high-resolution nanopatterning using thermal scanning probe lithography. Due to its sensitivity to thermal effects, PPC emerges as a promising candidate for precision nanofabrication. By elucidating its thermal decomposition mechanisms, including chain unzipping and random chain scission, we leverage those properties to achieve effective micro-/nanopatterning. Our results demonstrate that controlled thermal scanning and optimization of patterning parameters enable lateral resolutions down to 50 nm, along with grayscale structures featuring sub-nanometer vertical precision. Furthermore, by integrating PPC-based patterning with an optimized RIE process, grayscale patterns can be effectively transferred into the underlying SiO2 layer. This combined approach underscores the versatility of PPC as a resist material, particularly in applications requiring high aspect ratio structures and precise depth control. By uniting high-resolution patterning with efficient depth transfer, our work paves the way for the development of advanced nanostructures and functional materials for future technological applications. These findings lay a solid foundation for further exploration and expanded application of PPC-based resists in high-precision nanofabrication.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation and nano-patterning

A 6.5 wt% solution of polypropylene carbonate (PPC) in anisole was spin coated at 9000 rpm on SiO2/Si substrate (285-nm-thick thermally grown wet oxide on highly-dopped Si), followed by soft baking at 90 °C for 10 min, the thickness of the PPC is ~240 nm. Line nanopatterns were fabricated using a t-SPL system (Nanofrazor Explore, Heidelberg Instruments Nano AG) equipped with thermal cantilevers (Nanofrazor Monopede), which have an apex diameter of 15 ± 5 nm. During the patterning process, the tip temperature was varied from 300 to 1200 °C, while the indentation tip-sample voltage was set between 4.5 and 9.5 V.

For grayscale nanopatterns, a biaxial sinusoidal wave function \(f\left(x,y\right)=A[\cos \left({gx}\right)+\cos ({gy})]\) was implemented using the t-SPL system. The sinusoidal design was converted into grayscale bitmaps comprising 20 × 20 mm² pixel grids, with normalized depths discretized into 256 grayscale levels. In the imported bitmap, white pixels (minimum depth) corresponded to 0 nm, while black pixels (maximum depth) represented a depth of 45 nm. During t-SPL patterning, the heater temperature was set to 1050 °C, with a lateral step size of 20 nm, a scan speed of 25 μs per pixel, and a force pulse duration of 5 μs. Patterned depths were dynamically corrected using integrated in-situ AFM metrology, while the inset Kalman feedback system continuously adjusted actuation forces to ensure high-resolution depth control.

Reactive ion etching

The nanostructures were transferred from the PPC layer to the underlying SiO2 dielectric film using a RIE system (SENTECH Etchlab 200 plasma system). The dry etching process employed a high-density CHF3/Ar plasma with a flow rate of 40/40 sccm at a chamber pressure of 4 Pa. The RF power was set to 150 W. To prevent carbonization of the PPC layer during prolonged etching, a cyclic etching strategy was adopted. The etching process was paused for 60 seconds after every 60 seconds of operation to allow for cooling. This etch-pause cycle was repeated continuously until the PPC layer was fully removed and the pattern was successfully transferred into the SiO₂ layer.

AFM and SEM

Surface topography was characterized using a Bruker Dimension Icon atomic force microscope (AFM) operated in tapping mode under ambient conditions. An RTESPA-300 silicon probe (Bruker, nominal spring constant k = 40 N/m, resonant frequency ~300 kHz) was employed to scan a selected area with 512 Samples/Line and 512 Lines/frame, yielding a lateral pixel resolution of ~37 nm. The scan rate was maintained at 0.806 Hz (aspect ratio of 1) to minimize thermal drift. The amplitude setpoint was stabilized at 300 mV to ensure consistent tip-sample interaction. Raw data were processed using NanoScope Analysis software. All experiments were performed at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) with relative humidity below 40% to ensure measurement reproducibility.

SEM imaging was performed using a ZEISS Crossbeam 350 dual-beam system operating in SEM mode. Secondary electron images were acquired with the SE2 detector with an accelerating voltage of 5 kV, a working distance (WD) of 5.7 mm, and a magnification of 8 KX (corresponding to a scan width of 14.29 μm). The probe current was set to 252 pA (I Probe) with a scan speed of 3 (corresponding to a dwell time of ~200 ns/pixel). Images were captured at a resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels. Tilt correction was disabled (Tilt Corrn = Off) to preserve the original sample geometry.

References

Broers, A. N. Resolution limits for electron-beam lithography. J. Res Dev. 32, 502–513 (1988).

Garcia, R., Knoll, A. W. & Riedo, E. Advanced scanning probe lithography. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 577–587 (2014).

Howell, S. T., Grushina, A., Holzner, F. & Brugger, J. Thermal scanning probe lithography—a review. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 6, 21 (2020).

Paul, P. C., Knoll, A. W., Holzner, F., Despont, M. & Duerig, U. Rapid turnaround scanning probe nanolithography. Nanotechnology 22, 275306 (2011).

Carroll, K. M. et al. Fabricating nanoscale chemical gradients with ThermoChemical NanoLithography. Langmuir 29, 8675–8682 (2013).

Hu, H., Kim, H. & Somnath, S. Tip-based nanofabrication for scalable manufacturing. Micromachines 8, 90 (2017).

Carroll, K. M. et al. Speed dependence of thermochemical nanolithography for gray-scale patterning. Chemphyschem 15, 2530–2535 (2014).

Erbas, B. et al. Combining thermal scanning probe lithography and dry etching for grayscale nanopattern amplification. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 28 (2024).

Lee, W. K. et al. Direct-write polymer nanolithography in ultra-high vacuum. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 3, 52–56 (2012).

Chen, S. et al. Monolayer MoS2 nanoribbon transistors fabricated by scanning probe lithography. Nano Lett. 19, 2092–2098 (2019).

Hu, H., Cho, H., Somnath, S., Vakakis, A. F. & King, W. P. Silicon nano-mechanical resonators fabricated by using tip-based nanofabrication. Nanotechnology 25, 275301 (2014).

Liu, X., Howell, S. T., Conde‐Rubio, A., Boero, G. & Brugger, J. Thermomechanical Nanocutting of 2D Materials. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001232 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Thermomechanical nanostraining of two-dimensional materials. Nano Lett. 20, 8250–8257 (2020).

Zheng, X. et al. Patterning metal contacts on monolayer MoS2 with vanishing Schottky barriers using thermal nanolithography. Nat. Electron 2, 17–25 (2019).

Shani, L. et al. Thermal scanning probe and laser lithography for patterning nanowire based quantum devices. Nanotechnology 35, 255302 (2024).

Liu, X., Huang, Z., Zheng, X., Shahrjerdi, D. & Riedo, E. Nanofabrication of graphene field-effect transistors by thermal scanning probe lithography. APL Mater. 9, 011107 (2021).

Skaug, M. J., Schwemmer, C., Fringes, S., Rawlings, C. D. & Knoll, A. W. Nanofluidic rocking Brownian motors. Science 359, 1505–1508 (2018).

Grushina, A. Direct-write grayscale lithography. Adv. Opt. Technol. 8, 163–169 (2019).

Lassaline, N. et al. Optical fourier surfaces. Nature 582, 506–510 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Deterministic grayscale nanotopography to engineer mobilities in strained MoS2 FETs. Nat. Commun. 15, 6934 (2024).

Lisunova, Y., Spieser, M., Juttin, R. D. D., Holzner, F. & Brugger, J. High-aspect ratio nanopatterning via combined thermal scanning probe lithography and dry etching. Microelectron. Eng. 180, 20–24 (2017).

Wang, F. & Diesendruck, C. E. Polyphthalaldehyde: synthesis, derivatives, and applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 39, 1700519 (2018).

Rostami, M. et al. Multi- and gray-scale thermal lithography of silk fibroin as water-developable resist for micro and nanofabrication. Adv. Sci. 11, 2303518 (2024).

Luinstra, G. Poly(propylene carbonate), old copolymers of propylene oxide and carbon dioxide with new interests: catalysis and material properties. Polym. Rev. 48, 192–219 (2008).

Inoue, S., Koinuma, H. & Tsuruta, T. Copolymerization of carbon dioxide and epoxide. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Lett. 7, 287–292 (1969).

Zhu, Q., Meng, Y. Z., Tjong, S. C., Zhao, X. S. & Chen, Y. L. Thermally stable and high molecular weight poly(propylene carbonate)s from carbon dioxide and propylene oxide. Polym. Int 51, 1079–1085 (2002).

Muthuraj, R. & Mekonnen, T. Carbon dioxide–derived poly(propylene carbonate) as a matrix for composites and nanocomposites: performances and applications. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 303, 1800366 (2018).

Liu, B., Chen, L., Zhang, M. & Yu, A. Degradation and stabilization of poly(propylene carbonate). Macromol. Rapid Commun. 23, 881–884 (2002).

Phillips, O., Schwartz, J. M. & Kohl, P. A. Thermal decomposition of poly(propylene carbonate): End-capping, additives, and solvent effects. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 125, 129–139 (2016).

Peng, S. et al. Thermal degradation kinetics of uncapped and end-capped poly(propylene carbonate). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 80, 141–147 (2003).

Lu, X. L., Zhu, Q. & Meng, Y. Z. Kinetic analysis of thermal decomposition of poly(propylene carbonate). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 89, 282–288 (2005).

Cui, S., Wei, P. & Li, L. Thermal decomposition behavior of poly(propylene carbonate) in poly(propylene carbonate)/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 135, 2437–2446 (2018).

Nelson, B. & King, W. Modeling and simulation of the interface temperature between a heated silicon tip and a substrate. Nanosc. Microsc. Therm. 12, 98–115 (2008).

Gotsmann, B., Lantz, M. A., Knoll, A. & Dürig, U. Nanoscale thermal and mechanical interactions studies using heatable probes. Nanotechnology https://doi.org/10.1002/9783527628155.nanotech066 (2010).

Lassaline, N. Generating smooth potential landscapes with thermal scanning-probe lithography. JPhys mater. 7, 015008 (2023).

Knoll, A. W. et al. Probe-based 3-D nanolithography using self-amplified depolymerization polymers. Adv. Mater. 22, 3361–3365 (2010).

Rawlings, C. D. et al. Control of the interaction strength of photonic molecules by nanometer precise 3D fabrication. Sci. Rep. 7, 16502 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge fundings from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFB3405600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62274013 and 92163206), and Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12321004). The authors also thank the members from Wang Lab for the very fruitful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W., X.L., Y.H., and Y.D. co-supervised the project. X.L. conceived the original idea and designed the experiments. H.L. performed t-SPL, RIE etching experiments. J.L. and H.L. performed sample preparation, AFM and SEM experiments. Z.H., Z.J., H.M., S.Z., M.Z., W.F., and J.W. participated in sample preparation and data analysis. X.L. and H.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussions regarding the research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Li, J., Jin, Z. et al. Beyond binary patterning: polypropylene carbonate as a versatile thermal resist for high-fidelity grayscale Nanofabrication. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 19 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01032-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01032-z