Abstract

Compared with conventional manipulating methods, such as vacuum suction, electromagnetic adsorption, and mechanical clamping, gecko-inspired adhesives possess the ability of attaching on various surfaces with extensive applications in space operation, industrial manufacturing, etc. However, adhesive structures with high adhesion on one certain surface may lose their adhesive performance when gripping another surface. Achieving a good adhesion on objects with unknown surface morphology in a simple way is still a great challenge for gecko-inspired adhesives. Inspired by the interaction of the gecko’s actuating muscle and adhesive structures, we propose a smart adhesive film to adaptively manipulate objects with unknown surface morphology, consisting of magnetic artificial muscle and mushroom-shaped structures at the microscale. Controlled by the magnetic field, the adhesive film can conformally contact the target surfaces with flat/curved morphology or smooth/rough topography, and easily separated from the contacting interfaces, which process is performed without complex image recognition or detection sensors on pre-determining the detailed morphology of the opposing surfaces. This specific characteristic enables the smart adhesive film to successfully grip, transfer and release the unknown objects, extending the operating specification of gecko-inspired adhesives. Especially, in the manipulating process, the objects would not be dropped down from the smart adhesive film even if the magnetic field is suddenly removed, which is seldom achieved by other soft grippers. The proposed adhesion strategy extends gecko-inspired adhesives from specific types of surfaces to unknown surface morphology, opening an avenue for the development of gecko-inspired adhesive-based devices and systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to the interaction of van der Waals forces between the toes’ seta and the opposite surfaces1,2, geckos could quickly climb on vertical walls and horizontal ceilings3,4,5,6. Although each seta at micro/nano-scale on the toe surfaces provides the adhesive force of only several nano-forces, millions of setae could support the gecko to achieve stable attach on the contacting surfaces1,7,8. Compared with other adhesive methods, such as vacuum suction9,10, electromagnetic adsorption11,12,13, and mechanical clamping14, gecko-inspired adhesives incurred by the micro/nano-structures on the toe surfaces, possess the ability to attach on surfaces with various morphology and different materials, which have extensive applications in space operation, industrial manufacturing, etc.15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Consequently, inspired by the gecko’s adhesive behavior, achieving good adhesion performance on a series of target surfaces, composed of smooth or rough ones, flat or curved surfaces, is an important research direction, determining the development of gecko-inspired adhesives to some extent28,29,30,31.

As a typical short-range force, van der Waals force can act only with a situation of conformal contact between the adhesive structures and the opposing surfaces, giving rise to a possible thought on a design of enhancing effective contact area. For instance, adhesive structures at micro/nano-scale have been fabricated on curved substrates to increase the contact status as the manipulating surface is curved, demonstrating good performance on smooth and curved surfaces. Hierarchical structures32,33,34,35,36 or core-shell structures37,38,39,40 have been proposed to decrease the structural modulus for promoting the contact area as the manipulating surface is rough, exhibiting excellent adhesion performance on rough surfaces41. Structural stiffness variation has been proposed to enhance the contact status between adhesive structures and target surfaces controlled by the soft state with low modulus as well as maintaining contact status via the rigid state with high modulus, especially demonstrating high adhesion on non-flat surfaces42. However, the existing methods can only demonstrate effective adhesion on the surface with a specific morphology, i.e., an adhesive structure with high adhesion on one certain surface may lose its adhesive performance as contacting another surface. Subsequently, it is necessary to pre-determine the morphology of the target surfaces for adopting suitable adhesive structures, which unavoidably introduces a complex discriminant system based on image recognition or detection sensors43. Achieving good adhesion performance on objects with unknown surface morphology in a simple way is still a great challenge in engineering applications for gecko-inspired adhesives.

Different from artificial adhesive structures, natural geckos could climb on various walls without consideration of the morphology of the contacting surfaces, exhibiting amazing attachment behavior on opposing surfaces (Fig. 1a). This phenomenon can be attributed to the interaction of actuating muscle and adhesive structures, wherein the adhesive structures at micro/nano-scale provide the protentional high adhesion on target surfaces and the actuating muscle provides a sufficient deformation to guarantee a conformal contact between the micro/nano-structures and the target surface. Unfortunately, most researches were performed on designing and fabricating adhesive structures from the viewpoint of the micro/nano-structures on the gecko’s toe surface8,44,45,46,47,48,49,neglecting the action of the gecko’s muscle system, which may be a crucial aspect that the performance of artificial adhesives cannot be comparable to the gecko’s behavior. Thus, if the interaction of actuating muscle and adhesive structures can be reasonably integrated, the stable adhesion on unknown morphology could be promoted from the conceptual design to the engineering application.

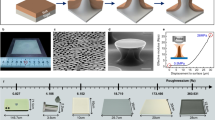

Schematic of stable manipulating objects with unknown surface morphology via integration of magnetic artificial muscle and adhesive structures. a Gecko’s behavior on the target surface under the interaction of actuating muscle and micro/nano-adhesive structures. b A smart adhesive film to adaptively manipulate objects with unknown surface morphology controlled by an electromagnet. c Function-integrated adhesive film based on magnetic artificial muscle and mushroom shaped micro-structures. d, e Demonstration of gripping and releasing flat or non-flat samples via the reversible deformation of magnetic artificial muscle and attachment performance of mushroom-shaped structures, respectively

Here, we propose an adhesive strategy to adaptively manipulate objects with unknown surface morphology (Fig. 1b), composed of magnetic artificial muscle to mimic the action of gecko’s muscle and mushroom-shaped structures at micro-scale to mimic the adhesive structures at the gecko’s toe surface50,51. In detail, the magnetic artificial muscle, in the form of film, is soft and could be bent with multiple degrees of freedom as exposed to an external magnetic field, leading to the feasibility of conforming the contour of the target that is beneficial for enhancing the contact area between adhesive structures and the target surface. Additionally, by applying an opposite magnetic field, the soft artificial muscle would be gradually separated from the target surface, thus corresponding to a simple approach to modulate the switch ability on attachment/detachment. That is, the interaction between the magnetic artificial muscle and mushroom-shaped structures can be utilized to obtain stable attachment and convenient detachment via adjusting the magnetic field direction exerted by an electromagnet.

Results and Discussion

Fig. 1c-i demonstrates the schematic of function integrated smart adhesive film based on magnetic artificial muscle and mushroom-shaped structures at the microscale. For the magnetic artificial muscle, the magnetic particles were inserted into the soft film for the balance of the deformability and the driving force, i.e., the soft film can be flexibly attached to the target surface under a free deformation, and also be easily detached from the opposing surface under the sufficient driving force. In detail, the magnetic particles are concentrated on a certain region at the micro-scale, in which the particles were selected in NdFeB (neodymium iron boron) for its excellent magnetic responsiveness and the micro-concentration of particles would not obviously affect the deformation of magnetic film. For the adhesive structures, the mushroom-shaped structures are designed owing to their high adhesion under the precondition of conformal contact to the target surface, wherein mushroom-shaped morphology at micro/nano-scale exhibits superior adhesive strength compared to other ones (such as flat, spherical, concave, and spatula morphology), because the mushroom-like cap can eliminate the stress singularity at the contacting interface and stabilize defects at the plate–substrate interface. The corresponding function integrated smart adhesive film is shown in Fig. 1c-ii, in which, obviously, the magnetic artificial muscle would not affect the adhesive performance of mushroom-shaped structures because of its good flexibility. The smart adhesive film is designed in the form of four-pieces to embrace the object under a positive magnetic field and to disengage the object under an inverse magnetic field, corresponding to the behavior of gripping and releasing.

Owing to the flexible deformation of magnetic artificial muscle and the adhesive performance of mushroom-shaped structures, the magnetic adhesive film could grip and release a surface without pre-determining the detailed surface morphology. For a flat surface (Fig. 1d), with an applied magnetic field (controlled by an external voltage), the magnetic adhesive film would adaptively contact the flat surface, resulting in a conformal contact between the mushroom-like structures and the target surface for the status of attachment. As gripping the target from one position to another, the magnetic would not be removed to guarantee the interfacial contact. For releasing the target, a reversed magnetic field is applied, the adhesive film would separate from the contact interface at the edge firstly, and then expand to the whole film, leading to the status of detachment. If the target surface is changed to a non-flat sample (Fig. 1e), the manipulation of the adhesive system is similar to that of the flat sample, in which, the magnetic adhesive film also could spontaneously conform with the non-flat surface in griping stage and separate from the edge to the center in releasing stage. Notably, in the transferring process, even if the magnetic field is suddenly removed by a specific uncontrollable factor, the target would not fall from the adhesive film due to the attachment performance of mushroom-shaped structures, which can be considered as an outstanding feature to guarantee operational safety. Consequently, based on the integration of magnetic artificial muscle and adhesive structures, stable manipulating objects with unknown surface morphology could be realized, which is seldom achieved by other gripping methods according to our best knowledge.

Fabrication of magnetic artificial muscle with particles concentrated in restricted regions

The magnetic artificial muscle is a crucial component in the proposed adhesive strategy, which should be soft for the flexible deformation with conformal contact to the target surface (attachment stage) and possess sufficient driving force to separate from the contacting interface (detachment stage). In general, the soft performance needs a small amount number of magnetic particles, whereas the feature of driving force needs a larger amount number of particles. On the basis of the conflicting requirements on the magnetic particles, the magnetic particles are designed to be restricted in micro-regions, i.e., micro-holes array. The fabrication method of the magnetic artificial in the form of film is demonstrated in Fig. 2a. Initially, a silicon template with a micro-holes array was obtained using the conventional MEMS techniques (Fig. 2a-i). A coating of C4F8 with low surface energy was deposited on the surface of the silicon template for demolding in the next process, and the fluororesin was spun coated on the silicon template (Fig. 2a-ii). After the fluororesin was cured, it was torn from the silicon template to generate a series of micro-structures of pillars, acting as the moulding template for obtaining micro-holes on silicon rubber (that is the base substrate of the magnetic film), as shown in Fig. 2a-iii. Subsequently, the prepolymer of silicon rubber was coated on the fluororesin template and then teared from the template after curing, forming micro-holes on the silicon substrate (Fig. 2a-iv, v). Magnetic particles (NdFeB) with size of roughly 1 μm were then scraped into the micro-holes (Fig. 2a-vi). After the solvent was totally volatilized, the magnetic particles were left in the holes and tightly adhered with the silicon rubber substrate, resulting in the designed soft magnetic artificial muscle. To demonstrate the durability of artificial muscle in practical applications, we conducted a systematic tension and compression cycle test on it (Fig. S1). The reciprocating tension and compression were carried out at a speed of 20 mm/min using a stretching machine to simulate the stress-strain cycle under actual working conditions. The microstructure of the artificial muscle before and after 100 cycles was characterized by ultra-depth-of-field microscopy. The results showed that before and after the 100-cycle test, the distribution of magnetic particles was basically consistent, the spatial distribution of magnetic particles in the polymer matrix did not show significant deviation, and no obvious debonding or fracture occurred at the interface between magnetic particles and the matrix. These fully confirm the structural stability of the embedded magnetic particles in complex mechanical environments, providing key support for the long-term reliable operation of the magnetically controlled adhesion system.

Fabrication of magnetic artificial muscle with particles concentrated in restricted regions. a Fabricating process of magnetic artificial muscle: (i) Preparation of silicon template with micro-hole array. (ii) Spin-coating of fluoropolymer resin. (iii) Curing and template release. (iv) Spin-coating of silicone rubber prepolymer on fluoropolymer mold. (v) Curing and demolding to form microstructured silicon rubber substrate. (vi) Magnetic particle (NdFeB) embedding. b Status of micro-holes on the silicon rubber template: the image of the micro-pore state of the silicone rubber template before magnetic powder filling(i), three-dimensional stereogram(ii), and pore depth(iii). The image of the micro-pore state of the silicone rubber template after magnetic powder filling (iv), three-dimensional stereogram(v) and pore depth(vi). The scale size is 100 μm

Notably, the filling degree, a ratio determined by the filling height of particles over the depth of the micro-hole, reflects the actuating performance under a modulated magnetic field, which can be considered as a valuable parameter to measure the fabricating effectiveness. Figure 2b demonstrates the micro-holes before and after the filling process of particles into the holes. Initially, the depth and width of holes are 100 μm and 60 μm, respectively. As the particles were inserted into the holes, the remaining depth of the holes was only 10 μm, corresponding to the filling degree of 0.9, which verifies the effectiveness of the fabricating approach. The high filling degree exhibits that the designed magnetic artificial muscle with particles concentrated in restricted regions can be achieved via the proposed fabricating process, mainly composed of moulding and blade coating.

Actuating performance of magnetic artificial muscle controlled by an electromagnet

To investigate the actuating performance of magnetic artificial muscle, the deformation amplitude and response time are adopted as the measure parameters. Figure 3a demonstrates the deformation amplitude of magnetic artificial muscle under an external magnetic field, with the vertical distance of H defined as the height of the free-standing end of the magnetic film separating from the original position in the vertical direction and the horizontal distance of L defined as the height of the free-standing end of the magnetic film separating from the fixed position in the horizontal direction (Fig. 3a-i). Clearly, with the increment of an external voltage, the parameter H becomes larger and larger, implying that a higher magnetic field could generate a larger driving force for a larger deformation (Fig. 3a-ii). In addition, the relationship between vertical distance H and applied voltage is in close proximity to the linearity, i.e., the deformation can be precisely modulated by a voltage. Figure 3a-iii demonstrates the variation of L versus the change of an applied voltage, in which, similarly, L becomes smaller and smaller owing to the fact that the free-standing end of the magnetic artificial muscle is closer to the fixed position. The detailed deformation behavior of the magnetic field under different voltages is shown in Fig. 3a-iv. Here, the bending behavior becomes more obvious with the increment of voltage, and especially the magnetic film can bend to touch the opposite surface with a voltage of 9 V, i.e., the electromagnet can provide sufficient deformation for the attachment and detachment of adhesive film.

Actuating performance of magnetic artificial muscle controlled by an electromagnet. a Deformation amplitude of magnetic artificial muscle under an external magnetic field with (i) demonstration of testing method, variation of vertical displacement (ii) and horizontal displacement (iii) versus applied voltage, respectively, and detailed deformation with different voltage (iv). b Response time of magnetic artificial muscle under an external magnetic field with (i) demonstration of testing method and (ii) variation of luminance with the twisting behavior of artificial muscle under different frequencies

The response time is another parameter determining the actuating behavior, defined as the time from the command to apply a magnetic field (input signal) to the completion of the maximum deformation of the magnetic artificial muscle (target state), which is tested by the twisting experiments with luminance extraction. Movies at different frequencies were shot by a camera, and each frame of the movie was subjected to grayscale processing and luminance extraction using data processing software, thereby obtaining the variation of luminance with the twisting behavior of magnetic artificial muscles (as shown in Fig. 3b-ii). When the magnetic artificial muscle is in a flat state (with the magnetic field off), the light shielding is weak, corresponding to a high luminance. When it’s in the distorted state (with the magnetic field open), the light shielding is enhanced, corresponding to a low brightness (Fig. 3b-i). By recording the time required for the luminance signal to decrease from the maximum value to the minimum value, the response times under different frequency inputs were obtained (Fig. S2). The results show that the magnetic artificial muscle has a faster response at different frequencies. Dynamic twisting movies at three different frequencies of 5 Hz, 10 Hz and 20 Hz are provided in Movies S1–S3. Under a 5 Hz magnetic field, magnetic artificial muscles twist at a constant frequency. When the frequency increases to 10 Hz and 20 Hz, it can still synchronously follow the changes in the magnetic field. These tests demonstrate the frequency response ability and the actuation capacity of magnetic artificial muscles under the magnetic field, ensuring the stable operation ability of the smart adhesive. Meanwhile, the phenomenon demonstrate the ability to control the behavior of artificial muscles by modulating the frequency of a magnetic field, offering an important guidance for the optimization of frequency-based adhesion regulation strategies in the future.

Adhesive performance modulated by an external magnetic field

It is well known that the adhesive structures can be used to stably grip flat surfaces, which, however, is difficult to manipulate non-flat surfaces due to the partial contact between the adhesive structures and the opposing surface. Here, a magnetic artificial muscle is designed to promote the adhesive structures to conformably contact with the target surface, wherein the adhesive structures on the top layer and the magnetic artificial muscle on the bottom layer with the demonstration and actual picture shown in Fig. 4a. The testing process of the smart adhesive film on the curved surface is shown in Fig. 4b. Initially, the adhesive film was fixed on the electromagnet. A glass ball with a diameter of 40 mm was selected as the test surface, and the adhesive film was kept away from the surface of the target (glass ball) (Fig. 4b-i). Subsequently, the glass ball went down to contact with the adhesive film. A magnetic field was applied to the adhesive film to make it conformally embrace the glass ball, thereby effectively contacting the adhesive structure with the curved surface (Fig. 4b-ii). After applying the magnetic field for 5 s, the glass ball was pulled out of the adhesive film using the testing equipment, and the separation force was recorded, which was defined as the adhesion force (Fig. 4b-iii).

Adhesive performance modulated by an external magnetic field. a Demonstration of magnetic field-controlled adhesive film with adhesive structures on the top layer and the magnetic artificial muscle on the bottom layer. b Testing process of adhesive film with a glass ball probe. c The adhesive force of magnetic adhesive gripper and flat gripper with a glass ball with a variation of voltage (i) and a comparison of adhesive force on the glass ball with or without voltage (ii). d Adhesive force of adhesive film on a raw egg with a variation of voltage (ii) with a demonstration of detailed surface morphology of egg (i)

In order to characterize the relationship between the magnetic field strength and the applied voltage, we measured the magnetic field intensity at different parts of the electromagnet under different voltages, including four points uniformly distributed on the edge and on point in the center (as shown in Fig. S3). The relationship between the magnetic field intensity on the surface of the electromagnet and the applied voltage was shown in Fig. S4. At each point, the magnetic field intensity increased nearly linearly with the increase of the applied voltage.

Fig. 4c-i demonstrates the adhesive force of the magnetic adhesive gripper (consists of the magnetic artificial muscle and the gecko-inspired adhesive) and the flat gripper (consists of the magnetic artificial muscle and a flat film without gecko-inspired adhesive structures to the glass ball under different voltages (i.e., different actuating magnetic fields), respectively. The experimental variables for testing the flat gripper were tightly controlled the same as for the magnetic smart gripper, i.e., as shown in Fig. 4b. Notably, as the magnetic field (via voltage) increases, both grippers exhibit larger deformation. The adhesive force of two grippers rises with voltage until reaching the saturation value. When no voltage is applied, the unactivated artificial muscle cannot wrap the object to achieve a full contact state, thus no adhesive force is observed (Fig. S5). As the magnetic field continues to increase through a voltage-controlled electromagnet, the deformation behavior of the adhesive film becomes larger and larger. Thus, the contact status between the adhesive film and the glass ball was improved for a large voltage, corresponding to a large adhesive force. With a voltage larger than 10 V, the generated magnetic force is sufficient to drive the soft film to conformably contact the glass ball, that is, even with a larger voltage, the contact status would not obviously improve, resulting in the saturation phenomenon. Conversely, the flat gripper generated only minimal adhesive force even when the artificial muscle achieved full actuation (maximal deformation at 18 V). In addition, the flat gripper generated only minimal adhesive force even when the artificial muscle achieved full actuation (maximal deformation at 18 V), which is much lower than that of the magnetic adhesive gripper under the same voltage. It confirms that the flat gripper cannot generate sufficient grip force without the adhesive structures, although the adaptive wrapping of the magnetic artificial muscle increases the contact area. This aligns with our hypothesis that the collaboration between the actuation from artificial magnetic muscle and the adhesion from the gecko-inspired microstructure is essential for high-performance grasping. Notably, if the voltage is suddenly removed for some unforeseen circumstances, the glass ball would not be dropped down from the adhesive film owing to the adhesive performance of the mushroom-shaped structures at the micro-scale, which is convenient for enhancing the operational stability and is difficult to be obtained by other soft gripping approaches, such as dielectric elastomer, ionic polymer metal composites, pure magnetic gripper, etc. Figure 4c-ii shows the adhesion of the adhesive film when the voltage is applied or removed. Applied voltage is the voltage applied externally without interruption throughout the test. The removed voltage specifically means that the power supply is activated during the contact process, and is cut off after the gripper fully contact with the target object. It can be found that the adhesive force is similar to each other with a voltage larger than 10 V, whereas the adhesive force for removing voltage is smaller than that for applying voltage as the voltage is smaller than 10 V. This phenomenon implies that the adhesive force with removing voltage is determined by the initial contact status incurred by the applied voltage. Consequently, with sufficient deformation obtained by a large voltage, the adhesive film can excellently contact the target surface with a stable grasping ability even as removing the voltage, which is necessary to sustain the manipulating safety without extra sensors to detect the contact status.

Except for the curved object with smooth, the proposed adhesive film can also manipulate a curved object with a rough surface, as shown in Fig. 4d. In Fig. 4d-i, the physical image of the egg and the topographic data of the top region of the egg were inserted, respectively, and the roughness were measured. The maximum height (Ra) and arithmetic mean deviation (Rz) of the contour are 3.483 μm and 18.536 μm. The roughness data of the top region of the raw egg shows. An object with such a rough surface is difficult to be grasped by a mushroom-shaped structure alone. In contrast, our proposed smart bonding membrane can successfully handle rough surfaces. The relationship between driving voltage and raw egg adhesion is shown in Fig. 4d-ii. Similar to the case of the smooth surface, the adhesive force is enhanced by increasing the applied voltage, which also contributes to the fact that the contact status between the adhesive film and the rough surface becomes better with a larger magnetic field. Specially, the adhesive force is continuously enlarged even as the voltage is increased to 20 V, without the saturation value appearing, implying that the rough surface needs a much larger actuating force to drive the soft film to conformally contact the target surface. Owing to the limitation of the electromagnet with the largest value of 20 V, the influence of greater voltage is not explored, which should also exist as a saturation value for the rough curved surface.

Demonstration of smart adhesive film on manipulating various objects

A manipulating system is developed to test the manipulating ability of magnetic field-controlled adhesive film, consisting of the smart adhesive film, the electromagnet for providing magnetic field, the signal source for supplying an external voltage on the electromagnet, the robotic arm and the control system for modulating the movement of robotic arm, as shown in Fig. 5a. Initially, the robotic arm approached the target and no voltage was applied to the electromagnet (as shown in Fig. 5b-i); Subsequently, a forward voltage is applied to the electromagnet, and the smart film gradually wraps around the target to achieve grasping and then transfer the target (as shown in Fig. 5b-ii); Finally, the electromagnet is applied to a reverse voltage, and the smart film gradually separates from the target, achieving the release function (as shown in Fig. 5b-iii).

Demonstration of smart adhesive film on manipulating various objects. a Smart adhesive based manipulating system to carry out operating behaviors with constitute of manipulating system. b The diagram of the voltage-driven smart adhesive film-based grab-and-release principle, which consists of no-voltage approach to the target (i), forward voltage-driven smart film wrapping to grab the target for transfer (ii), and reverse voltage-driven smart film separating from the target for release (iii). c Smart adhesive film-based manipulating processes of gripping, transferring and releasing various objects, consisting of (i) glass rod, (ii) glass plate, (iii) glass ball, and (iv) raw egg

Fig. 5c demonstrates the smart adhesive film-based manipulating system to operate various objects, composed of glass rod, glass plate, glass ball, and raw egg. For the glass rod with a length of roughly 300 mm, it can be successfully gripped under an external magnetic field, transferred to the desired position with maintaining the magnetic field, and released as removing the magnetic field (Fig. 5c-i). In addition, the corresponding dynamic manipulating process is shown in Movie S4 in the supporting information. This process implies that the smart adhesive film based on magnetic artificial muscle and mushroom-shaped adhesive structures at the micro-scale could effectively manipulate the non-flat surface, which is difficult to realize by conventional adhesive methods. Similarly, a glass plate with an area of 100 mm × 100 mm, a glass ball with a diameter of 40 mm, a raw egg with a length of 35 mm and a height of 50 mm, can also be stably gripped, transferred and released at the anticipated position. The relevant dynamic operation processes are provided with supporting information in Movies S4 to S7. To eliminate the influence of the adhesive properties of the material itself on the experimental results, we conducted the experiment using a gripper without neither the artificial muscle nor the mushroom-shaped structure (named passive gripper), which is made of the same material as the smart adhesive (Fig. S6), and also carried out tests on four typical bases: glass plate, glass rod, ocean ball, and egg (Movies S8–S11). Meanwhile, in order to highlight the importance of mushroom-shaped microstructures to this work, we replaced the gecko-inspired adhesive with a flat film and carried out the comparative experiments with it under an activated magnetic field (named flat gripper) (Fig. S7, movies S12–S15). The dimensions of the flat gripper, the value of the applied voltage and the contact time were strictly set to coincide with the experiments carried out with the smart gripper, the specific experimental parameters are depicted in Table S1. The experimental results show that neither the passive gripper nor the flat gripper can achieve effective grasping under all test conditions, confirming that the adhesive force of the material itself is insufficient and stable grasping cannot be achieved solely relying on the intrinsic adhesive characteristics of the material itself. The successful application of smart adhesive films on various objects has once again confirmed the superiority of the magnetic artificial muscle-based adhesion strategy on both flat and non-flat objects with smooth or rough surfaces, which may promote the development of gecko inspired adhesives.

Conclusion

In summary, we propose a smart adhesive film to adaptively manipulate objects with unknown surface morphology, composed of magnetic artificial muscle and mushroom-shaped structures at the microscale. The proposed smart adhesive overcomes the inability of conventional gecko-inspired adhesives to adapt to unknown contour objects. Compared to the strategy of grasping objects with unknown contours through variable stiffness structures, the smart adhesive proposed in this paper makes the adhesive structure contact the target through a magnetic field, thereby eliminating the process of mechanically applying preload force52, effectively avoiding the potential damage caused by high interfacial stress to the target object, and can adaptively adhere to objects with morphologies at any position. The simple mechanism configuration reduces the complexity of the bonding system21. Compared with pressure-controlled (e.g., pneumatic and hydraulic) soft grippers, the proposed smart adhesive has a faster millisecond-level response time16. It can complete the adsorption and release actions in a short time, perform flexible picking and placing, and significantly improve the operational efficiency53. The gecko-inspired adhesive structure enables smart adhesives to be used in adapting to surfaces of various materials and thus has a wide range of applications. However, some factors (e.g., high temperature, dust, humidity, oil, etc.) that can influence the adhesive structure or prevent the adhesive structure from contacting with the target surface can adversely affect the adhesion performance, which can be solved by optimizing the adhesive structure and the materials, which is beyond the scope of this paper. Activated by the magnetic field, the smart adhesive film could conformably contact the target surface and separate from the contacting interface without extra exploration on the surface morphology, i.e., stable manipulating objects with unknown surface morphology. For the magnetic artificial muscle, the magnetic particles of NdFeB are concentrated on a certain region at the micro-scale of the soft film for the balance of the deformability and the driving force, providing sufficient deformation for conformal contact and satisfactory driving force for separation behavior, as well as a fast response time. For the adhesive structures, the mushroom-shaped structures are used owing to its high adhesion as conformal contacting the target surface. The magnetic adhesive film possesses the ability to grip, transfer, and release various objects with different morphology, such as smooth/rough topography and flat/curved morphology. The traditional objects have been successfully manipulated without complex image recognition or detection sensors, consisting of glass rod, glass plate, glass ball, and raw egg. Especially, even if the magnetic field is suddenly removed in the manipulating process, the objects would not drop down from the adhesive film owing to the attachment of the microscale mushroom-shaped structures, guaranteeing operation safety. The manipulating capacity of objects with unknown morphology is seldom achieved by conventional gecko-inspired adhesives and soft grippers. The proposed adhesion strategy can promote the application of gecko-inspired adhesives to a wide range of material surfaces, from specific surfaces to unknown surfaces with various morphology, and has long-term durability (Fig. S8), opening an avenue for the development of gecko-inspired adhesives.

Methods

Materials

Unless stated otherwise, solvents and chemicals were obtained commercially and used without further purification. Silane coupling agent KH560 of Xin Hengyan was obtained from Beijing Kaiguo Technology Co., LTD. (China); Epoxy resin of McLean was obtained from Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co., LTD. (China); Neodymium iron boron (NdFeB) particles was obtained from Shanghai Mingli Trading Co., LTD. (China); Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) of Dow Corning Sylgard 184 was obtained from Dow Corning Inc. (USA).

Fabrication of magnetic artificial muscle in the smart adhesive film

The nano-scale C4F8 was deposited on the surface of the silicon mold for passivation treatment. 50 grams of PDMS monomer and 5 grams of curing agent were mixed, stirred for 5 min, vacuum treatment for 5 min, and then poured onto the passivated silicon mold, and vacuum treatment for 5 min twice, and curing in a 60 °C oven for 1 h to obtain the inverse structure. The inverse structure is coated with PDMS, vacuum treatment for 5 min, and then spin coating (the first stage is 1000 RPM, lasting 9 s; The second stage is 5000 RPM for 50 s). After natural curing, the structured flexible film substrate is removed. Low dimensional treatment of 9 g (90%) magnetic material for 20 h. Stir 10 ml anhydrous ethanol and 0.2 g (2%) silane KH560 coupling agent in a 50 ml beaker for 10 min until dissolved, mix with the treated magnetic material, and stir for another 30 min. Bake the beaker at 60 °C for 2 h. Then add 10 ml of anhydrous ethanol to the beaker, stir for 10 min, and add 0.8 g (8%) epoxy resin, stir for 1 h to get the scraping material. The structured flexible film substrate is attached to the PET film, and the scraping material is moved to one end of the substrate with a pipet, and then scraped to the other end. The base was heated at 85 °C for 90 s and the surface was wiped after heating to complete the preliminary preparation of the actuator. The actuator was then coated with PDMS and vacuumed for 5 min. The bottom PET film is spin coated at 9000 RPM. The heat curing PDMS completes the preparation of the actuator.

Fabrication of mushroom-shaped structures in the smart adhesive film

Mushroom-shaped adhesive structure was made with PDMS through the currently commonly used molding process. In this paper, the mold was prepared by the double-sided exposure process proposed by this team before, which can realize the fabrication of mushroom-shaped structure with controllable structure and good uniformity. The body and the curing agent of the PDMS were mixed and stirred uniformly in a ratio of 10:1, and then poured onto the mold and evacuated for 10 min. Subsequently, spin coating was performed, and the curing was completed in an oven at 80 °C for 1 h. Finally, the structure was obtained by demolding. The thickness of backing layer was controlled by changing the casting parameters. The mushroom-shape micro-structures were about 20 µm height with a 25 µm spacing, and the diameter of contact tip and pillar were 16 and 12 µm, respectively.

Structures and adhesion characterization

The microstructure of the adhesive material was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SU8010, Hitachi, Japan). The adhesion force of material was characterized by computer servo pull–pressure test machine (PT–1176, Baoda, China). The adhesion of smart adhesive film on target surfaces was measured by Load–Pull mode, that is, the probe is first contacted with the sample to generate a certain contact area, and then the reverse movement is performed until complete separation. The maximum tensile force generated before separation was defined as the maximum adhesion force. The smart adhesive film was attached on the base of electromagnet. The testing surface was moved down at a speed of 1 mm/min to contact with the sample and a magnetic field was applied on the adhesive film for conformal embracing the target surface. The target surface was then moved up until the testing surface were completely separated from the adhesive film. The adhesive force can be deduced via the time–force curve.

References

Autumn, K. et al. Evidence for van Der Waals Adhesion in Gecko Setae.

Sun, W., Neuzil, P., Kustandi, T. S., Oh, S. & Samper, V. D. The Nature of the Gecko Lizard Adhesive Force. Biophys. J. 89, L14–L17 (2005).

Russell, A. P. A Contribution to the Functional Analysis of the Foot of the Tokay, Gekko Gecko (Reptilia: Gekkonidae). J. Zool. 176, 437–476 (1975).

Autumn, K. et al. Dynamics of Geckos Running Vertically. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 260–272 (2006).

Autumn, K., Dittmore, A., Santos, D., Spenko, M. & Cutkosky, M. Frictional Adhesion: A New Angle on Gecko Attachment. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 3569–3579 (2006).

Autumn, K. Mechanisms of Adhesion in Geckos. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 1081–1090 (2002).

Autumn, K. et al. Adhesive Force of a Single Gecko Foot-Hair. Nature 405, 681–685 (2000).

Geim, A. K. et al. Yu. Microfabricated Adhesive Mimicking Gecko Foot-Hair. Nat. Mater. 2, 461–463 (2003).

Fujita, M. et al. Development of Universal Vacuum Gripper for Wall-Climbing Robot. Adv. Robot. 32, 283–296 (2018).

Tao, D. et al. Controllable Anisotropic Dry Adhesion in Vacuum: Gecko Inspired Wedged Surface Fabricated with Ultraprecision Diamond Cutting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1606576 (2017).

Eich, M. & Vogele, T. Design and Control of a Lightweight Magnetic Climbing Robot for Vessel Inspection. In 2011 19th Mediterranean Conference on Control & Automation (MED); IEEE: Corfu, Greece, 2011; pp 1200–1205.

Tavakoli, M., Viegas, C., Marques, L., Pires, J. N. & De Almeida, A. T. OmniClimbers: Omni-Directional Magnetic Wheeled Climbing Robots for Inspection of Ferromagnetic Structures. Robot. Auton. Syst. 61, 997–1007 (2013).

Eto, H. & Asada, H. H. Development of a Wheeled Wall-Climbing Robot with a Shape-Adaptive Magnetic Adhesion Mechanism. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA); IEEE: Paris, France, 2020; pp 9329–9335.

Wang, Y. et al. Mechanically Interlocked [a n]Daisy Chain Adhesives with Simultaneously Enhanced Interfacial Adhesion and Cohesion. Angew. Chem. 136, e202409705 (2024).

Sitti, M. & Fearing, R. S. Synthetic Gecko Foot-Hair Micro/Nano-Structures as Dry Adhesives. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 17, 1055–1073 (2003).

Glick, P. et al. A Soft Robotic Gripper With Gecko-Inspired Adhesive. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 3, 903–910 (2018).

Song, S., Majidi, C. & Sitti, M. GeckoGripper: A Soft, Inflatable Robotic Gripper Using Gecko-Inspired Elastomer Micro-Fiber Adhesives. In 2014 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems; IEEE: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014; pp 4624–4629.

Hawkes, E. W., Jiang, H., Christensen, D. L., Han, A. K. & Cutkosky, M. R. Grasping Without Squeezing: Design and Modeling of Shear-Activated Grippers. IEEE Trans. Robot. 34, 303–316 (2018).

Alizadehyazdi, V. & Spenko, M. A Microstructured Adhesive Gripper with Piezoelectric Controlled Adhesion, Cleaning, and Sensing. Smart Mater. Struct. 28, 115037 (2019).

Alizadehyazdi, V., Bonthron, M. & Spenko, M. An Electrostatic/Gecko-Inspired Adhesives Soft Robotic Gripper. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5, 4679–4686 (2020).

Jiang, H. et al. A Robotic Device Using Gecko-Inspired Adhesives Can Grasp and Manipulate Large Objects in Microgravity. Sci. Robot. 2, eaan4545 (2017).

Ruotolo, W., Brouwer, D. & Cutkosky, M. R. From Grasping to Manipulation with Gecko-Inspired Adhesives on a Multifinger Gripper. Sci. Robot. 6, eabi9773 (2021).

Bae, W. G. et al. Enhanced Skin Adhesive Patch with Modulus-Tunable Composite Micropillars. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2, 109–113 (2013).

Autumn, K. Gecko Adhesion: Structure, Function, and Applications. MRS Bull. 32, 473–478 (2007).

Alapan, Y. et al. Soft Erythrocyte-Based Bacterial Microswimmers for Cargo Delivery. Sci. Robot. 3, eaar4423 (2018).

Sangbae, K. et al. Smooth Vertical Surface Climbing With Directional Adhesion. IEEE Trans. Robot. 24, 65–74 (2008).

Frost, S. J. et al. Gecko-Inspired Chitosan Adhesive for Tissue Repair. NPG Asia Mater. 8, e280–e280 (2016).

Zhou, M., Pesika, N., Zeng, H., Tian, Y. & Israelachvili, J. Recent Advances in Gecko Adhesion and Friction Mechanisms and Development of Gecko-Inspired Dry Adhesive Surfaces. Friction 1, 114–129 (2013).

Kizilkan, E. & Gorb, S. N. Combined Effect of the Microstructure and Underlying Surface Curvature on the Performance of Biomimetic Adhesives. Adv. Mater. 30, 1704696 (2018).

Su, M. et al. Non-Lithography Hydrodynamic Printing of Micro/Nanostructures on Curved Surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 14234–14240 (2020).

Ruffatto, D., Parness, A. & Spenko, M. Improving Controllable Adhesion on Both Rough and Smooth Surfaces with a Hybrid Electrostatic/Gecko-like Adhesive. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20131089 (2014).

Murphy, M. P., Kim, S. & Sitti, M. Enhanced Adhesion by Gecko-Inspired Hierarchical Fibrillar Adhesives. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 1, 849–855 (2009).

Drotlef, D., Amjadi, M., Yunusa, M. & Sitti, M. Bioinspired Composite Microfibers for Skin Adhesion and Signal Amplification of Wearable Sensors. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701353 (2017).

Hu, H. et al. Bioinspired Hierarchical Structures for Contact-Sensible Adhesives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109076 (2022).

Kasper, J. Y. et al. Actin-templated Structures: Nature’s Way to Hierarchical Surface Patterns (Gecko’s Setae as Case Study). Adv. Sci. 11, 2303816 (2024).

Xue, L. et al. Hybrid Surface Patterns Mimicking the Design of the Adhesive Toe Pad of Tree Frog. ACS Nano 11, 9711–9719 (2017).

Tian, H. et al. Core–Shell Dry Adhesives for Rough Surfaces via Electrically Responsive Self-Growing Strategy. Nat. Commun. 13, 7659 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Self-Adaptive Core-Shell Dry Adhesive with a “Live Core” for High-Strength Adhesion under Non-Parallel Contact. Engineering 2025, S2095809925000256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2024.12.035.

Tan, D. et al. Humidity-Modulated Core–Shell Nanopillars for Enhancement of Gecko-Inspired Adhesion. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 3, 3596–3603 (2020).

Bae, W.-G. et al. Fabrication and Analysis of Enforced Dry Adhesives with Core–Shell Micropillars. Soft Matter 9, 1422–1427 (2013).

Tan, D. et al. Switchable Adhesion of Micropillar Adhesive on Rough Surfaces. Small 15, 1904248 (2019).

Li, S. et al. Switchable Adhesion for Nonflat Surfaces Mimicking Geckos’ Adhesive Structures and Toe Muscles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 39745–39755 (2020).

Zong, W. et al. Behaviours in Attachment-Detachment Cycles of Geckos in Response to Inclines and Locomotion Orientations. Asian Herpetological Research 13, 125–136 (2022).

Liu, Q. et al. Adhesion Enhancement of Micropillar Array by Combining the Adhesive Design from Gecko and Tree Frog. Small 17, 2005493 (2021) .

Shahsavan, H. & Zhao, B. Conformal Adhesion Enhancement on Biomimetic Microstructured Surfaces. Langmuir 27, 7732–7742 (2011).

Liu, K., Du, J., Wu, J. & Jiang, L. Superhydrophobic Gecko Feet with High Adhesive Forces towards Water and Their Bio-Inspired Materials. Nanoscale 4, 768–772 (2012).

Jeong, H. E., Lee, J.-K., Kim, H. N., Moon, S. H. & Suh, K. Y. A Nontransferring Dry Adhesive with Hierarchical Polymer Nanohairs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 106, 5639–5644 (2009).

Qu, L., Dai, L., Stone, M., Xia, Z. & Wang, Z. L. Carbon Nanotube Arrays with Strong Shear Binding-On and Easy Normal Lifting-Off. Science 322, 238–242 (2008).

Kim, S. & Sitti, M. Biologically Inspired Polymer Microfibers with Spatulate Tips as Repeatable Fibrillar Adhesives. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 261911 (2006).

Gorb, S. N. & Varenberg, M. Mushroom-Shaped Geometry of Contact Elements in Biological Adhesive Systems. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 21, 1175–1183 (2007).

Gorb, S., Varenberg, M., Peressadko, A. & Tuma, J. Biomimetic Mushroom-Shaped Fibrillar Adhesive Microstructure. J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 271–275 (2007).

Wang, D. et al. Sensing-Triggered Stiffness-Tunable Smart Adhesives. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf4051 (2023).

Shahsavan, H., Salili, S. M., Jákli, A. & Zhao, B. Thermally Active Liquid Crystal Network Gripper Mimicking the Self-Peeling of Gecko Toe Pads. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604021 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation (52175546, 12102248), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (grant No. xzd012023046), and Funded Project of Shanghai Aerospace Science and Technology (No. SAST2022-078).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.T. and Q.C. conceived the idea. H.T., F.L. and D.Z. developed the materials for the magnetic artificial muscle and adhesive structures. H.T., H.Z. and F.L. performed the structural characterization of the magnetic artificial muscle and adhesive structures. F.L., D.Z., Y.T. and Y.L. designed and performed the adhesive performance testing. F.L., X.Z., Y.T. and Y.L. performed the actuating performance testing of magnetic artificial muscle. A.H., W.D., J.S. and L.S. designed and conducted the object manipulation experiments. H.T. and Q.C. supervised and directed the research. H.T. and F.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

41378_2025_1033_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supporting Information for Stable manipulating objects with unknown surface morphology via integration of magnetic artificial muscle and adhesive structures

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F., Zhang, D., Zhu, H. et al. Stable manipulating objects with unknown surface morphology via integration of magnetic artificial muscle and adhesive structures. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 164 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01033-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01033-y