Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) materials are intensively studied as promising materials for gas sensors owing to their large surface area and low working temperature. In this work, we report the synthesis of a layered SnS2 single crystal by a chemical vapor deposition (CVD) approach for NO2 sensing. By tuning the growth temperature, high-quality crystals with a lateral size over 3 mm are obtained in 30 min. The 2D SnS2 sensor with optimized thickness (~15 nm) shows a low detection limit (2 ppb), a fast recovery time (66 s/1 ppm), and a high response (~4702% @ 1 ppm NO2) at room temperature (RT) under UV illumination. An in-situ Kelvin probe force microscope is employed to reveal the high selectivity of SnS2 through qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis of charge transfer behavior, including the directions and amount of charge transfer, upon exposure to different gases. In-situ Raman and first-principles density functional theory calculations further confirm the sensing mechanism toward NO2. Both experimental and theoretical results suggest that 2D SnS2 holds promising potential as an RT NO₂ sensing material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metal oxide semiconductors (MOSs) have been widely employed as sensing materials, due to their simplicity, low cost, and mature manufacturing process1. However, most MOSs require a high working temperature (typically over 200 °C), which increases power consumption and adversely impacts the long-term stability2. Recently, two-dimensional (2D) materials with a high surface-to-volume ratio have emerged as promising candidates for sensing hazardous analytes at relatively low working temperature3. As for 2D materials, Graphene (Gr) is widely utilized for gas sensing, owing to its zero band gap property, atomic layered structure, and high surface area4. While without surface modification, Gr-based sensors suffer from poor selectivity to target gases and a long recovery time (trec) at room temperature (RT)5,6. Therefore, other 2D semiconductor materials, especially transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), are gaining increasing attraction7,8.

SnS2 is a non-toxic and n-type semiconductor (with a bandgap of 2.18–2.44 eV) with a large interlayer distance of 0.59 nm that allows gas molecules to adsorb/desorb on the surface and interlayer active sites9. Moreover, it has a larger electronegativity (5.49 eV) compared with other TMDs, and has been explored for sensing of various polar molecules such as NO2 and NH37,10,11. Especially, NO2 is one toxic pollutant gas that significantly impacts the ecological system and human health12. Theoretical calculations revealed that due to smaller adsorption energy (−0.43 eV) and stronger orbital hybridization between NO₂ molecules and SnS2, SnS2 was able to selectively detect NO2 among other interfering gases, including CO2, SO2, NH3, acetone, ethanol, methanol, and formaldehyde9. Up to now, different morphologies such as SnS2 nanoflowers, nanoparticles, and vertically aligned SnS2 nanosheets, which are synthesized through hydrothermal and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) methods, are employed in NO2 sensors13,14. However, since SnS2 shows a strong temperature dependency, many reported SnS2 sensors operate over 100 °C11,14,15. Although some works have shown the ability to detect NO2 at RT via defect engineering and light activation strategies, they still encounter challenges associated with a low response, a slow recovery process, and are unable to achieve a limit of detection (LOD) below the criterion of 10 ppb set by Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)16,17,18,19,20.

In this regard, to further enhance the overall sensing properties of RT sensors, modulating the thickness of 2D materials can be an effective strategy. It has been reported that a higher response can be obtained with reduced thickness17,21. For example, by annealing in air, Li et al.17 observed that raising the temperature from 100 °C to 200 °C led to a decrease in the thickness of SnS2 nanoflower from 25 nm to 15 nm, and a corresponding increase in the response value from about 13 to 24.2. Whereas, they failed to further decrease the thickness since SnS2 oxidation is observed when the annealing temperature is over 200 °C17. Moreover, in addition to modulated thickness, a high density of grain boundaries exists in agglomerated SnS2 nanosheets or nanoflowers; these cases also influence the sensor performance22. Thereby, it is difficult to precisely elucidate the role of thickness contributions to the improved sensing performance.

Therefore, investigation of the effect of SnS2 thicknesses on NO2 sensing, as well as in situ revealing the microscopic sensing mechanism, is crucial to enhance NO₂ detection. Utilizing sensors based on a single flake with different thicknesses, exfoliated from SnS₂ single crystals, allows for the study of the intrinsic sensing mechanism by eliminating grain boundary effects. In an effort to obtain high-quality single crystals, chemical vapor transport (CVT) is a mature method. However, it is often time-consuming, typically requiring several hours or even days to complete23,24. In this work, we proposed a facile CVD method for the growth of high-quality SnS2 crystals to obtain single SnS2 flakes. Compared with conventional CVT methods, the growth period of SnS2 crystals with large lateral size (>3 mm) was successfully shortened to 30 min. The thickness-dependent sensing performance of sensors based on a single flake was studied under UV illumination at RT. Among them, the sensor based on 15 nm-SnS2 flake demonstrated the highest sensing response (~4702% @ 1 ppm NO2), high selectivity, and an ultralow LOD (2 ppb). To further reveal the sensing mechanism, in-situ Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) and Raman were utilized to study the charge transfer mechanism and adsorption characteristic between SnS2 and NO2 molecules. The theoretical results based on the first principles (DFT) also confirmed the adsorption capacity of SnS2 for NO2 gas molecules.

Results and discussion

Morphology and microstructure of SnS2

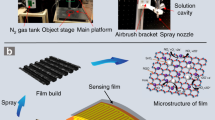

SnS2 crystals were synthesized via CVD using SnO2 and S powder as precursors, as shown in the schematic diagram in Fig. 1a. The Sn source and S source were placed at the center and upstream of the furnace, respectively. The corresponding temperature profile is depicted in Fig. 1b (additional details are provided in the Experimental Section). In contrast to established crystal growth techniques like CVT, which can take hours or days, the growth time in our CVD method was successfully shortened to a mere 30 min23,24. By varying the growth temperature from 820 °C to 920 °C with increments of 20 °C, we regulated the crystallite size (Fig. S1) and obtained large-sized golden crystals (given in Fig. 1c, lateral size >3 mm) with a clean surface at the downstream of the tube. Figure 1d illustrates the crystal structure of SnS2, wherein the blue dashed box represents the initial unit cell of SnS2. 2H–SnS2 exhibits a hexagonal CdI2-type layered structure, characterized by Sn atoms sandwiched between two layers of S, arranged as S–Sn–S25. Within each individual layer, strong covalent bonds hold the S and Sn atoms together, while weaker van der Waals (vdW) forces bind the adjacent layers25.

Figure 2a shows the Raman spectra of 2D SnS2 grown at temperatures ranging from 820 to 920 °C. A prominent peak near 315 cm−1 (A1g, out of plane) was consistently observed across all SnS2 flakes, regardless of the growth temperature. No peaks corresponding to Sn2S3, SnS, or SnOx (where x = 1, 2) were detected26. In addition, the Raman spectra of the SnS2 crystal grown at 880 °C with different thicknesses are shown in Fig. S2. Figure S2a and b demonstrate the optical and atomic force microscope (AFM) images of the corresponding SnS2 flake with different thicknesses. For bulk materials, the Raman spectra in Fig. S2c show two active vibrational modes, which are in-plane vibration (Eg) and out-of-plane vibration mode (A1g) at 206.6 cm−1 and 315.9 cm−1, respectively. Upon reducing the thickness to the nanoscale, the in-plane Eg mode becomes undetectable in thin SnS2 flakes. This phenomenon is presumably ascribed to the reduction of in-plane scattering centers in SnS2 with nanometer thickness14. Moreover, a decrease in peak intensity and a blue shift of the A1g peak position were observed in Fig. S2d as the thickness reduced. Moreover, AFM and Raman spectroscopy were used to evaluate the chemical stability of the SnS2 by storing it under ambient air and inert N2 atmospheres for 9 days, respectively, as shown in Fig. S3 and Fig. S4. Both SnS2 flakes stored at two conditions revealed no significant changes, including surface morphologies, intensities, and positions of Raman peaks. These results indicate good chemical stability of SnS2. X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a powerful technique for characterizing the crystallinity and phase structure of materials, including SnS2 single crystals, as shown in Fig. 2b and Table S1. The grown SnS2 crystals exhibited a hexagonal structure (JCPDS PDF number 23-0677) with lattice parameters of a = b = 0.36 nm and c = 0.59 nm. The strong diffraction peak observed at 15.2° corresponded to (0001) crystal plane of SnS2, while those smaller peaks at 30.4°, 46.3°, and 63.2° were indexed to (0002), (0003), and (0004) planes. The dominance of the (000 N) peaks (N = 0, 1, 2, etc.) in the diffraction pattern clearly indicated that SnS2 preferentially grew along the Z-direction, with the (0001) plane serving as the basal plane. The peak intensity of the (0001) plane for the six sets of samples showed an initial rise from 820 °C to 880 °C, followed by a decrease as the temperature rose to 920 °C (the detailed XRD pattern of SnS2 grown at 920 °C is presented in Fig. S5). Thus, the SnS2 synthesized at 880 °C showed the highest crystallinity within the range from 820 °C to 920 °C. It is suggested that at relatively low growing temperatures, the comparatively high reaction barrier energy may hinder complete sulfurization27,28,29. Conversely, excessively high temperatures could accelerate the crystallization process, potentially impairing the crystal structure and quality30.

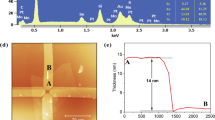

a Raman spectrum of the SnS2 crystals grown at temperatures ranging from 820 to 920 °C. b XRD patterns of SnS2 crystals grown at temperatures between 820 and 920 °C. XPS spectra of c Sn 3d and d S 2p of SnS2 crystals synthesized at 820 °C, 880 °C, and 900 °C, respectively. e TEM image and f HRTEM of SnS2 crystal grown at 880 °C grown SnS2 crystal. The inset exhibits the corresponding SAED pattern. g EDS spectrum for the SnS2 crystal synthesized at 880 °C

In addition, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was employed to investigate the surface states and chemical composition of 2D SnS2. Figure 2c, d depicts the high-resolution spectra and fitting curves for Sn 3d and S 2p peaks of SnS2 samples grown at 820 °C, 880 °C, and 900 °C, respectively. In Fig. 2c, two characteristic peaks observed at around 485.8 and 494.2 eV correspond to Sn3d5/2 and Sn3d3/2 states of Sn4+31. The S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 peaks were located at approximately 160.8 and 162.0 eV, respectively, which are assigned to S2−32. The ratios of Sn:S for three samples were calculated to be ~1:1.9, denoting the presence of S vacancies in the obtained SnS2. Specifically, for the SnS2 grown at 820 °C, in addition to the peaks related to the Sn–S bond (486.00 eV and 494.40 eV), peaks attributed to the Sn–O bond (located at 487.00 eV and 495.40 eV) were also detected33. The Sn–O bond can be attributed to the residual SnO2 in the SnS2 sample, which acts as an n-type dopant, shifting the binding energies of Sn and S to higher values34.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) were employed to characterize the microscopic structure of 2D SnS2 crystals grown at 880 °C. Figure 2e shows a TEM image of the prepared SnS2 crystal, revealing its layered stacking structure. The high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image (Fig. 2f) displays the lattice fringe interval of 0.32 nm, corresponding to the {10\(\bar{1}\)0} lattice planes of hexagonal-structured SnS2. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern in the inset of Fig. 2f exhibits sixfold symmetric diffraction spots, demonstrating high-quality crystallinity of this crystal with a vertical growth along the [0001] direction. The composition of the crystals was further confirmed by EDS (Fig. 2g), and the spectrum only shows signals of S and Sn, indicating a high purity of the synthesized crystals.

2D SnS2 flakes with different thicknesses, exfoliated from crystals grown at 880 °C, were transferred between two adjacent electrodes. Figure S6 displays the electrical behavior of sensors based on SnS2 using different electrode configurations. Due to the high Schottky barrier between the channel material and Au electrodes, the sensor with Au electrodes showed a higher baseline resistance (>2 GΩ), approaching our instrument’s detection limit35. In addition, during the NO2 sensing tests, the resistance will further increase, which may exceed the measurement range of the instrument and thus provide inaccurate results. Therefore, we employed Gr as the electrode in subsequent device fabrication, and the schematic diagram is shown in Fig. 3a. Gas sensors based on different SnS2 thicknesses (7.5, 15, 40, 75, 80, and 100 nm) with Gr electrodes were fabricated and tested at RT under UV illumination (details are provided in the Experiment section). Their corresponding optical and AFM images are shown in Figs. 3b and S7. The thickness dependence of the NO2 sensing performance toward 1 ppm NO2 was investigated in Fig. 3c, where the 15 nm-SnS2-based sensor showed the highest response value of around 4702%. Initially, when the material thickness is relatively small, the response value of the sensors increased with the thickness of the SnS2 flakes from 7.5 nm to 15 nm. This enhancement can be attributed to a lower adsorption energy at the interlayer compared to that at the material surface36, that gas adsorption occurs not only on the surface but also within the interlayer spaces. Therefore, increasing the number of layers facilitates the intercalation of NO2 between the layers and subsequent adsorption within the vdW gaps of SnS237. However, as the thickness further increases, gas diffusion into the underlying layers can be hindered. Whereas the depletion region in SnS2 caused by NO2 adsorption is confined to the near-surface region, the adsorption of NO2 exerts a negligible influence on the conductivity of the underlying layers of thicker SnS2 flakes. Therefore, the diminished accessibility of NO2 to the underlying SnS2 layers with increasing flake thickness reduces the utility of sensing materials and consequently deteriorates the response38.

a Schematic diagram of the NO2 sensor based on a 15 nm-SnS2 with Gr electrodes. b AFM image of this sensor, with an inset profile indicating a thickness of 15 nm. c Responses of SnS2 gas sensors with varied thicknesses to 1 ppm NO2. d Response/recovery time (tres/trec) of 15 nm-SnS2-based sensor toward 1 ppm NO2. e Dynamic response curve of 15 nm-SnS2-based sensor to NO2 in the concentration range of 2–1500 ppb (the inset shows the magnified response curve to 2 ppb and 10 ppb NO2). f Scattered response values of the as-prepared 15 nm-SnS2 based sensor to different concentrations NO2 and the relevant linear fitting curve. g Selectivity of 15 nm-SnS2-based NO2 sensor among 9 interfering gases (Methyl: Methylbenzene, Formal: Formaldehyde). h Comparison of trec and response value with other 2D material-based NO2 sensors (NS nanosheet, NG nanograin). i Comparative analysis of the sensing responses observed in this study across various concentrations of NO2

The tres/trec of 15 nm-SnS2-based sensor for 1 ppm NO2 is 508/66 s as demonstrated in Fig. 3d, and the corresponding resistance curve is shown in Fig. S8. The dynamic response of 15 nm-SnS2 to different NO2 concentrations ranging from 2 to 1500 ppb is shown in Fig. 3e. The sensor was capable of detecting NO2 at a concentration as low as 2 ppb with an obvious response value of 12.6%. Figure 3f shows the sensor response as a function of NO2 concentration. The response of the sensor increased linearly with the concentration of NO2. Besides, the selectivity performance of 15 nm-SnS2 based sensor was measured and depicted in Fig. 3g. n-type SnS2, indicated from the transfer curve in Fig. S6e, showed an increased resistance (p-type doping) for oxidizing gases (electron acceptors), while a decreased resistance (n-type doping) for reducing gases (electron donors). Moreover, the response value to interfering gases (1 ppm H2S and 10 ppm SO2, NH3, CO2, methylbenzene, acetone, ethanol, and formaldehyde) was much lower than that to 1 ppm NO2, indicating a good selectivity owing to the favorable alignment of the SnS2 Fermi level and partially occupied molecular orbitals (POMO) of NO213. The long-term stability is shown in Fig. S9. Despite an initial decrease in sensing performance over the first few days, the response subsequently stabilized, demonstrating an acceptable long-term stability.

Figure 3h, i, as well as Table S2 summarize the performance of various sensors based on 2D materials in terms of the trec, response value, and LOD8,11,18,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Some sensors are reported to achieve a rapid recovery speed but demonstrated low sensitivity, or possessed a wide detection range but were incapable of detecting ppb-level NO2, which does not meet the criterion established by CFR (10 ppb) as listed in Table S2. While our work exhibited a relatively faster trec (66 s) and a lower LOD (2 ppb), as well as a higher response (~4702% @ 1 ppm NO2), compared with other 2D NO2 gas sensors operating at RT. The good sensing performance can be ascribed to two main reasons. Firstly, light illumination generates a substantial number of photogenerated charge carriers, which increases the carrier density favorable for gas adsorption and accelerates the electron transfer speed between SnS2 and NO27,17. Secondly, a certain amount of sulfur vacancies may enhance the catalytic activity of the material by serving as reaction sites during adsorption, probably inducing a stronger adsorption of NO2 on the SnS2 surface17.

To clarify the sensing mechanism, a single SnS2 flake was transferred onto a conductive substrate, and in situ KPFM was performed on SnS2 under exposure to target gases, and variation in the surface potential (SP) was mapped. Two typical oxidizing gases (NO2 and SO2) and one typical reducing gas (H2S) were chosen as model gases. In KPFM, the contact potential difference (VCPD) between the scanned sample and metal tip facilitates the acquisition of the topography and SP, and the work function of SnS2 (\({W}_{\text{S}}\)) can be obtained from VCPD via the following equation47:

where \({E}_{F,S}\) is the Fermi level of SnS2 and \({E}_{0}\) is vaccum level, Wtip is the work function of metal tip and q is the elementary charge. The changes of VCPD values indirectly correspond to the shift in \({E}_{F,S}\), and surface band bending induced by the analyte gas. The potential images of SnS2 on the Au substrate before and after introducing NO2 are depicted in Fig. S10a, b. The difference between work functions of SnS2 (5.2 eV) and Au (5.1 eV) causes energy level bending at the junction of the two materials (Fig. 4a)48. When exposed to NO2, electrons will be transferred from the SnS2 to NO2 due to its oxidizing property, resulting in a downward shift of \({E}_{F,S}\), and a decreased \({V}_{\text{CPD}}\) value of SnS2, as demonstrated in Figs. 4a and S10b. Conversely, reducing gases elicits the opposite effect. We also performed in-situ KPFM characterization under 1 ppm of SO2 and H2S, and the resulting potential profile and VCPD values are depicted in Figs. 4b and S10c, respectively. Consistent with the dynamic sensing response, the VCPD variation trends for oxidizing and reducing gases were opposite. Upon exposure to NO2 and SO2, a reduced \({V}_{\text{CPD}}\) value was observed, which aligned with the abovementioned trend, suggesting p-type doping. For H2S, VCPD increased, which implied n-type doping. It means that the SnS2-based sensor was able to identify oxidizing and reducing gases. Moreover, for oxidizing gases, the variation in the decrease in the Fermi level provides a qualitative indication of the extent of electron loss, and a detailed deviation process is presented in the Supporting Information. The most pronounced change of VCPD is observed under NO2 exposure, indicating a larger shift in \({E}_{F,S}\). This suggests a greater degree of charge transfer from SnS2 to NO2 compared to SO2. The results corresponded well to sensing measurements that the sensor exhibited a typical p-type response to NO2, with the highest response value, highlighting the high selectivity of SnS2. We further analyzed the gas adsorption characteristics using in situ Raman spectroscopy. Figure 4c shows the Raman spectra of the SnS2 flake before and after the introduction of NO2. The intensity of A1g vibration mode exhibited a significant decrease upon exposure to NO2, with this trend aligning well with the findings previously reported13. NO2 adsorption acts as hole doping with the introduction of impurity energy levels, inducing the dampening of phonon enlargement and weakening the vibration intensity49. Additionally, a slight red shift was observed for the A1g peak, suggesting that NO2 molecules may be physically adsorbed in the van der Waals gap of layered SnS2 structures50.

First-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to investigate the adsorption of NO2 on SnS2, employing a 2 × 2 × 1 supercell of SnS2. Figure 5a, b illustrates the energetically most stable molecular configuration of NO2 on the SnS2 surface. The adsorption energy of NO2 were evaluated using:

where Etotal presents the total energy of the system after adsorbing a single gas molecule, Egas and Ematerial denote the energies of the gas molecule and the sensing material prior to adsorption. The calculated adsorption energy of NO2 was found to be −0.126 eV, with N–S and N-Sn adsorption distances of 3.68 Å and 4.52 Å, respectively. The negative adsorption energy indicated an exothermic adsorption process, suggesting that NO2 can spontaneously adsorb onto the SnS2 surface. In addition, Fig. 5c shows the charge density difference (CDD) of SnS2 after NO2 adsorption, where the yellow and cyan regions represent electron accumulation and depletion, respectively. Bader charge analysis revealed a transfer of 0.05 electrons from SnS2 to NO2, leading to the formation of a charge density region at the adsorption site. Figure 5e presents the band structure diagram of SnS2 with adsorbed NO2. The SnS2 system exhibited semiconducting behavior with impurity levels existing in the band gap due to NO2 adsorption. The projected density of states (PDOS) of the adsorption system is depicted in Fig. 5f, where new states emerged near the valence band maximum and conduction band minimum, which can be attributed to the adsorption of NO2. The above results exhibited the interfacial charge transfer and electronic structure evolution caused by NO2 adsorption.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we employed the CVD method to realize the growth of high-quality SnS2 single crystals with a lateral size over 3 mm in a short dwelling time (30 min). Subsequently, a single SnS2 flake-based sensor was obtained through facile exfoliation. The sensing properties of SnS2 with different thicknesses were investigated under UV illumination at RT. SnS2 single flake with a thickness of 15 nm exhibited the highest response (~4702%) to 1 ppm NO₂ among thicknesses ranging from 7.5 nm to 100 nm. The sensor also showed complete recovery to the baseline with a trec (66 s) and was capable of detecting NO2 down to 2 ppb. We also conducted an in-depth study of the sensing mechanism of SnS2 by experimental and theoretical approaches. In-situ KPFM was employed to qualitatively and semi-quantitatively analyze the electron transfer properties of SnS2 when exposed to various gases. The observed results were in accordance with the gas sensing results, confirming the selective sensing behavior to NO2. Furthermore, in-situ Raman and DFT calculations explained the adsorption capacity of SnS2 for NO2 and the charge transfer occurring at the solid-gas interface. The realization of the NO2 sensor with high sensitivity opens up new possibilities for a wide range of applications, including human health care, industrial pollution supervision, and environmental monitoring.

Materials and methods

Material growth

The CVD process was performed at atmospheric pressure within a tubular furnace. In a typical growth process, 20 mg SnO2 powder (purity 99.5%, Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd.) was added in a ceramic boat positioned at the center of the heating zone, while 700 mg of S (purity 99.999%, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) powder was added in another quartz boat approximately 20 cm upstream. Prior to elevating the temperature, the furnace was purged with high-purity Ar at a flow rate of 300 sccm for 15 min to remove any residual gases (e.g., O2 and H2O) and maintain an inert atmosphere. Subsequently, the furnace was heated to the growth temperature (820–920 °C) with a ramp rate of 35 °C min−1, and then dwelled for 30 min before cooling to room temperature naturally. The evaporation temperature of S powder was set as 150 °C using a heating belt. During the growing process, Ar was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 60 sccm.

Device fabrication

Silicon with a 285 nm layer of SiO2 was employed as a substrate. The substrates were firstly cleaned in acetone, isopropanol, and ethanol for 5 minutes each, followed by drying with N2 gas and plasma treatment for 20 min. The electrode patterns were defined using ultraviolet photolithography. Then, Ti/Au (5/20 nm) were deposited as metal electrodes using magnetron sputtering deposition, followed by a liftoff process in acetone. Then Gr was mechanically exfoliated and transferred to Au electrodes, followed by alignment transfer of SnS2 flake to bridge Gr electrodes to fabricate Gr–SnS2–Gr sensors. The SnS2 flake was mechanically exfoliated from its crystals employing the standard Scotch tape-based cleavage approach. For the Au–SnS2–Au sensor, the SnS2 flake was transferred between two adjacent Au electrodes on the substrate.

Characterization

The vibration modes of SnS2 flakes were confirmed using Raman spectroscopy (inVia Qantor) with a laser wavelength of 532 nm and laser power of 1 mW. The phase structure of SnS2 was characterized by XRD (D-8 Bruker) technique using Cu Kα radiation. The single-crystalline nature of SnS2 was characterized by the SC-XRD (Bruker D8 Venture) technique using Cu Kα radiation. The chemical binding energies of the elements were analyzed via XPS (Thermo Fischer ESCALAB 250Xi). The morphologies of the prepared SnS2 crystals were studied using field emission TEM (Tecnai G2 F20 S-TWIN, 200 kV). AFM and KPFM ((Dimension Icon)) were used to measure the thicknesses of the transferred SnS2 flakes and the potential difference between SnS2 and the Au substrate.

Gas-sensing measurements

The sensor testing setup is shown in Fig. S11. The sensor was placed in a sealed chamber on a hot and cold stage (HCS621G-PM, INSTEC, United States) for gas sensing measurement, and N2 was utilized as the background carrier gas. A gas inlet connected to the test gas source, while a gas outlet was linked to an exhaust gas collector. Real-time resistance–time (R–T) curves were conducted using a Keithley 2636B. The specific concentration of the target gas was achieved by diluting the target gas with N2 before introducing it into the chamber. Once the resistance of the sensor reached a stable state after exposure to the target gas, N2 was switched to flow through the chamber until it returned to its initial baseline. All tests were performed under UV illumination at RT by using a light source (UVEC-4II, Shenzhen Lamplic Science CO., Ltd.) with a light intensity of 27.2 mW cm−2. The sensing response for oxidizing gas was calculated as (Rg − Ri)/Ri * 100%, and for reducing gas was (Ri − Rg)/Rg * 100%, where Ri is the initial resistance and Rg is the resistance after exposure to the target gas. Furthermore, tres and trec were defined as the time required to reach the maximum value of 90% and 10% after loading and unloading of the target gas, respectively.

Density functional theory calculation

The first-principles calculations were implemented in the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP). The semi-local generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the form of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) was adopted for exchange and correlation interactions, and the projector augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials were adopted. A 2 × 2 × 1 supercell SnS2 with one NO2 molecule adsorbed was chosen as the crystal structure, and a vacuum layer of 20 Å was used to separate the cells to mimic the 2D system. For geometric optimization, the Hellman-Feynman forces of single atoms are set to be less than 0.02 eV Å, and the energy cutoff is set to be 520 eV. The K points were sampled by Monkhorst–Pack with a 5 × 5 × 1 mesh. For electronic properties calculation, the single electronic step is converged to 1 × 10−9 eV, and K points are chosen to be 9 × 9 × 1.

References

Wei, Y. et al. Hydrothermal synthesis of Ag modified ZnO nanorods and their enhanced ethanol-sensing properties. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 75, 327–333 (2018).

Galstyan, V., Comini, E., Baratto, C., Faglia, G. & Sberveglieri, G. Nanostructured ZnO chemical gas sensors. Ceram. Int. 41, 14239–14244 (2015).

Yang, J. F. et al. Enhancing selectivity of two-dimensional materials-based gas sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2420393 (2025).

Kim, S. et al. Highly selective ammonia detection in NiO-functionalized graphene micropatterns for beef quality monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2407885 (2024).

Ghosh, A., Late, D. J., Panchakarla, L. S., Govindaraj, A. & Rao, C. N. R. NO2 and humidity sensing characteristics of few-layer graphenes. J. Exp. Nanosci. 4, 313–322 (2009).

Recum, P. & Hirsch, T. Graphene-based chemiresistive gas sensors. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 11–31 (2024).

Chen, H. W. et al. Suspended SnS2 layers by light assistance for ultrasensitive ammonia detection at room temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1801035 (2018).

Hau, H. H. et al. Enhanced NO2 gas-sensing performance at room temperature using exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets. Sens. Actuators A 332, 113137 (2021).

Jiang, M., Xu, J., Munroe, P. & Xie, Z. H. SnS2 monolayer as a promising candidate for NO2 sensor or capturer with high selectivity and sensitivity: a first-principles study. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 152, 107073 (2022).

Xu, Y. & Schoonen, M. A. A. The absolute energy positions of conduction and valence bands of selected semiconducting minerals. Am. Mineral. 85, 543–556 (2000).

Liu, D., Tang, Z. L. & Zhang, Z. T. Nanoplates-assembled SnS2 nanoflowers for ultrasensitive ppb-level NO2 detection. Sens. Actuators B. 273, 473–479 (2018).

Greenberg, N. et al. Different effects of long-term exposures to SO2 and NO2 air pollutants on asthma severity in young adults. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A. 79, 342–351 (2016).

Ou, J. Z. et al. Physisorption-based charge transfer in two-dimensional SnS2 for selective and reversible NO2 gas sensing. ACS Nano. 9, 10313–10323 (2015).

Kumar, A. et al. Growth and NO2 gas sensing mechanisms of vertically aligned 2D SnS2 flakes by CVD: experimental and DFT studies. Sens. Actuators B. 353, 131078 (2022).

Wang, C. Y. et al. Pt-modified nanosheet-assembled SnS2 hollow microspheres for low temperature NO2 sensors. Sens. Actuators B. 417, 136118 (2024).

Gu, D. et al. Visible-light activated room temperature NO2 sensing of SnS2 nanosheets based chemiresistive sensors. Sens. Actuators, B. 305, 127455 (2020).

Li, Y. Y. et al. Ppb-level NO2 sensing properties at room temperature of ultra-thin SnS2 nanopetals annealed at different temperatures. Sens. Actuators B. 370, 132398 (2022).

Liu, D., Tang, Z. L. & Zhang, Z. T. Visible light assisted room-temperature NO2 gas sensor based on hollow SnO2@SnS2 nanostructures. Sens. Actuators B. 324, 128754 (2020).

Sun, Q. et al. Synergically engineering defect and interlayer in SnS2 for enhanced room-temperature NO2 sensing. J. Hazard. Mater. 421, 126816 (2022).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. 40 CFR Part 53, Subpart B - Procedures for Testing Performance Characteristics of Automated Methods for SO2, CO, O3, and NO2. eCFR. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/chapter-I/subchapter-C/part-53/subpart-B (accessed 9 Jun 2025).

Tonezzer, M. Comparative gas-sensing performance of 1D and 2D ZnO nanostructures. Sens. Actuators B. 220, 1152–1160 (2015).

Wang, L. L. et al. Grain-boundary-induced drastic sensing performance enhancement of polycrystalline-microwire printed gas sensors. Adv. Mater. 31, 1804583 (2019).

Khimani, A. J., Chaki, S. H., Deshpande, M. P. & Tailor, J. P. Study of indium and antimony incorporation into SnS2 single crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 507, 180–188 (2019).

Tripathi, P., Kumar, A., Bankar, P. K., Singh, K. & Gupta, B. K. Large-scale production and optical properties of a high-quality SnS2 single crystal grown using the chemical vapor transportation method. Crystals 13, 1131 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Broadband photodetectors based on 2D group IVA metal chalcogenides semiconductors. Appl. Mater. Today 15, 115–138 (2019).

Smith, J., Meek, P. E. & Liang, W. Y. Raman scattering studies of SnS, and SnSe. J. Phys. C 10, 1321–1333 (1977).

Wang, Z. G. & Pang, F. In-plane growth of large ultra-thin SnS2 nanosheets by tellurium-assisted chemical vapor deposition. RSC Adv. 7, 29080–29087 (2017).

Zhao, Y., Huang, J. Z., Chen, J. Q., Liu, Y. W. & Zhai, T. Y. Chemical-vapor-deposition-grown 2D transition metal dichalcogenides: A generalist model for engineering electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nano Res. 16, 101–116 (2023).

Zhang, X., Lai, J. W. & Gray, T. Recent progress in low-temperature CVD growth of 2D materials. Oxf. Open Mater. Sci. 3, itad010 (2023).

Somphonsane, R., Chiawchan, T., Bootsa-ard, W. & Ramamoorthy, H. CVD synthesis of MoS2 using a direct MoO2 precursor: a study on the effects of growth temperature on precursor diffusion and morphology evolutions. Materials 16, 4817 (2023).

Morgan, W. E. & Wazer, J. R. V. Binding energy shifts in the X-ray photoelectron spectra of a series of rlelated group IV-a compounds. J. Phys. Chem. 77, 964–969 (1973).

Khan, Z. et al. Three-dimensional SnS2 nanopetals for hybrid sodium-air batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 257, 328–334 (2017).

Hao, J. Y. et al. Hierarchical SnS2/SnO2 nanoheterojunctions with increased active-sites and charge transfer for ultrasensitive NO2 detection. Nanoscale 10, 7210–7217 (2018).

Suh, J. et al. Doping against the native propensity of MoS2: degenerate hole doping by cation substitution. Nano Lett. 14, 6976–6982 (2014).

You, J. et al. Effect of graphite as electrodes on electrical and photoelectrical behavior of multilayer MoS2 and WS2 FETs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 69, 5324–5329 (2022).

Babar, V., Vovusha, H. & Schwingenschlög, U. Density functional theory analysis of gas adsorption on monolayer and few layer transition metal dichalcogenides: implications for sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 6076 (2019).

Qin, Z. Y. et al. Effect of layer number on recovery rate of WS2 nanosheets for ammonia detection at room temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 414, 244–250 (2017).

Xie, H. F. et al. Temperature and thickness dependence of the sensitivity of nitrogen dioxide graphene gas sensors modified by atomic layer deposited zinc oxide films. RSC Adv. 5, 28030–28037 (2015).

Kim, C. et al. Self-formed channel devices based on vertically grown 2D materials with large-surface-area and their potential for chemical sensor applications. Small 14, 1704116 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Gas sensors based on mechanically exfoliated MoS2 nanosheets for room-temperature NO2 detection. Sensors 19, 2123 (2019).

Chang, J. N. et al. Visible light enhanced NO2 sensing performance of Au nanoparticles modified SnS2 hierarchical structure at room temperature. Sens. Actuators B. 385, 133633 (2023).

Wu, R. Z. et al. 2D/2D SnS2/SnSe2 van der Waals heterostructure for highly sensitive room-temperature NO2 sensor: Key role of interface contact. Chem. Eng. J. 466, 143369 (2023).

Yang, C. et al. Flexible NO2 sensors based on WSe2 nanosheets with bifunctional selectivity and superior sensitivity under UV activation. Sens. Actuators, B. 333, 129571 (2021).

Xu, Y. S. et al. Edge-enriched WS2 nanosheets on carbon nanofibers boosts NO2 detection at room temperature. J. Hazard. Mater. 411, 125120 (2021).

Han, Y. T. et al. Interface engineered WS2/ZnS heterostructures for sensitive and reversible NO2 room temperature sensing. Sens. Actuators B. 296, 126666 (2019).

Kwon, K. C. et al. SnS2 nanograins on porous SiO2 nanorods template for highly sensitive NO2 sensor at room temperature with excellent recovery. ACS Sens. 4, 678–686 (2019).

Bisht, P. et al. Gas sensing properties of PLD grown 2D SnS film: Effect of film thickness, metal nanoparticle decoration, and in situ KPFM investigation. Small 20, 2307037 (2024).

Nithyapriya, M. S., Sivalingam, M. M., Navaneethan, M. & Archana, J. Flower-like SnS2/rGO composites with efficient iodide-triiodide redox performance for counter electrodes in Pt-free dye-sensitized solar cells. Opt. Mater. 157, 116243 (2024).

Guan, K. J. et al. Atomic Nb-doping of WS2 for high-performance synaptic transistors in neuromorphic computing. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 132 (2024).

Huang, J. L. et al. Chemisorption of NO2 to MoS2 nanostructures and its effects for MoS2 sensors. ChemNanoMat 5, 1123–1130 (2019).

Acknowledgements

C. F. Guo and L. Liu contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first authors. The authors acknowledge the funding support from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20230234, BK20243004, BK20221065), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62125112, 62371448, 62204254, 62301553, 62401563, 52203356), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Science (XDB0520301), and Suzhou Municipal Bureau of Science & Technology (Grant No. ZXL2023339, SJC2023004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, C., Liu, L., Cai, Z. et al. Two-dimensional SnS2 single crystal for sensitive NO2 detection at room temperature. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 246 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01054-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01054-7