Abstract

High overtone bulk acoustic resonators (HBAR) are advantageous for on-chip quantum acoustodynamics (QAD) system as it gives access to stream of phonon modes with high lifetime in the microwave frequency range while retaining low power consumption and microscale footprint. In this paper we present a HBAR based on barium strontium titanate (BST) thin-film mounted on sapphire with modes exhibiting frequency quality factor product (fQ) of 1.72 × 1015 Hz which is the highest reported for a bulk acoustic wave resonator utilizing polycrystalline ferroelectric material as a means for acoustic wave excitation. Unlike other piezoelectric based HBARs, the DC field-induced piezoelectricity utilized in this work offers multiple on-chip tuneability of resonator’s dynamic parameters such as phonon lifetime, frequency modulation and coupling. The higher overtone feature can enable qubit(s) in a hybrid quantum circuit to interact with one or more acoustic modes to form a quantum transducer. Here, the multi-mode resonator exhibits a unique DC bias dependency, and this feature of the ferroelectric thin film adds control variables that efficiently tune static and dynamic material, mechanical and electrical properties of the device. The resonator records a loaded quality factor of 180,000 in X band and 140,000 in the L band when measured at 10 K. A controllable robust resonator with simple fabrication technique offering high fQ can be a strong platform to be used in QAD circuits for applications in metrology, quantum memory and quantum information processing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The field of quantum acoustodynamics (QAD) has taken significant strides by taking advantage of both the technological advancement and the knowledge acquired through the field of quantum electrodynamic (QED) systems1,2. Micro and nanoelectromechanical systems (M/NEMS) have a plethora of mechanical resonators to offer which include engineered waveguides, phononic crystals, surface acoustic wave (SAW) and bulk acoustic wave (BAW) resonators which can couple with microwave and optical waveguides or superconducting qubits making it an attractive choice for circuit QAD applications3,4,5,6,7,8. In such hybrid quantum systems, the acoustic resonators act as the harmonic oscillator while the superconducting qubit becomes the anharmonic counterpart permitting access to quantum phenomenon on a macroscopic scale3. Mechanical resonators operating in GHz frequency can be cooled to their quantum ground state by using dilution refrigeration, and the use of acoustic wave offers more isolation from the environment when compared to electromagnetic wave which can be critical parameter for preserving quantum information3,9. The Q factor reflects the extent of how well the acoustic modes are decoupled or isolated from the environment10. Coupling between mechanical waves and the superconducting qubits is achieved by utilizing piezoelectric materials excited by electric fields from either microwave resonators or the qubit3,4,5,7,11.

Radiofrequency (RF) MEMS resonators utilizing BAW and SAW are backbone for the compact handheld communication systems. The slower phase velocity of acoustic waves when compared to electromagnetic waves has enabled confinement of acoustic modes into a much smaller form factor enabling on-chip integration with other subsystems. Piezoelectric materials used for SAW and BAW resonators, depending on the dimensional, elastic properties, and electrode configurations can excite both lateral and longitudinal acoustic modes over a wide range of frequency under the influence of an alternating electric field12,13. The piezoelectric transducer in most BAW devices are excellent means for generating acoustic modes from MHz to as high as 110 GHz14,15,16. Ability to harness hundreds of modes over a wide spectrum of frequency and the choice to choose the high Q tank (or substrate) from diverse piezoelectric and non-piezoelectric materials has enabled BAW resonators to be used in multiphysics domains like spintronics, optomechanics, and hybrid quantum systems7,17,18. Film bulk acoustic resonators (FBAR) and solidly mounted resonators (SMR) have matured applications in RF filtering and duplexer designs where the figure of merit (FoM) is the product of effective coupling coefficient and the quality factor (\({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\,\times Q\))13,19,20. Scaling up of operating frequency in BAW resonators are either made possible through thinning down of the piezoelectric transducer or by exploiting harmonics in the piezoelectric. For the latter case, it can be disadvantageous since \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) has inverse dependence with the harmonic number21. This is the reason why overtones from standing waves in a piezo on substrate (TPoS) configurations are preferred for excitation of higher frequency modes with high Q overtones like HBAR or LOBAR22,23,24.

HBAR has gained lots of attention in hybrid quantum systems because of its capability to offer high Q multimode over a wide microwave frequency range. The robust nature of the resonator has permitted HBAR to couple with superconducting qubits by either on-chip or flip-chip configurations7,25. Recent works from ETH, Zurich, demonstrated entanglement of two acoustic modes through the beam-splitter interactions between two modes of a HBAR25 and the use of two HBAR interacting with two qubits is reported in works from Aalto University26; both groups where able to perform iSWAP operations which is essential for quantum random access memory (QRAM) applications.

The work reported here follows an unconventional route of electroacoustic transduction with a thin ferroelectric film being used for excitation of high Q modes at cryogenic temperature in frequencies spanning from L to X band (and higher). BST and other ferroelectric thin films can add switchable and tuneable capabilities in RF filters through either capacitive tuning (in LC resonator) or induced piezoelectric effect (in acoustic resonator)27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Recent works on HBAR focuses on material and interface engineering to achieve an impedance matched acoustic stack to maximize the energy injection from transducer to the high Q cavity16,34,35,36. Here, in this paper, Ba0.5Sr0.5TiO3 (BST) excites and modulates the high Q modes existing in the sapphire substrate, and the DC dependence nature of the transducer material is used to (i) enhance, (ii) alter, and/or (iii) cease the acoustic energy injection into the substrate. At the current stage of our study, impedance matching between the thin films and the bulk substrate has not been conducted. Despite this, through DC biasing and temperature control, HBAR modes around 9.16 GHz exhibiting Q factor of 180,000 at 10 K are recorded (with fQ = 1.72 × 1015 Hz). The reported phonon lifetime of around 8 µs in the C band and 6 µs in the X band is the highest amongst any reported ferroelectric thin film-based resonators. This work can serve as a strong platform for QAD as the use of HBAR as a quantum resource has been demonstrated for fundamental physics exploration, quantum error correction, metrology, and quantum computing7,11,25,26.

Device configuration

HBAR consists of an acoustic wave generator and a substrate or cavity for retaining the GHz oscillations. The primary considerations for HBAR design involve a) the transducer material b) the substrate and c) the electrode configuration (or excitation/readout scheme). Here, BST thin film is made the transducer for introducing multifunctionality offered by ferroelectrics in the resonator. Thin film BST (Ba0.5Sr0.5TiO3) of thickness 500 nm is deposited with pulsed laser deposition using KrF excimer laser (248 nm) at fluence of 2 J/cm2 at 700 °C. A double side polished (thickness ~ 500 µm; roughness < 5 Å) C-axis sapphire substrate (MTI Corp.) is used as the acoustic cavity. Sapphire is a favourable choice due to its high material Q over wide range of microwave frequencies and temperatures37.

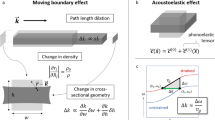

HBAR can be broadly categorised as either 1-port (reflection type) or 2-port (transmission type) depending on which the electrode and device configurations can vary22,31,32,33,34,35,36. For hybrid systems with either on-chip or flip chip technology, the excitation of the piezoelectric and readout are done using the coupling from electric field from the qubit7,11; for this case, the bottom electrode maybe exempted which can enhance the Q. In this work, the driving and sensing of the resonator is accomplished through a parallel plate metal insulator metal (MIM) configuration, where an AC and DC field excites acoustic waves through the induced piezoelectric effect in the ferroelectric film as shown in Fig. 1(a) and the electrical readout is established through a CPW GSG probe as shown in Fig. 1(c). The substrate traps the acoustic energy launched from the transducer by reflecting it within the two parallel faces which has solid-air interfaces. Owing to the choice of device design, the substrate will confine maximum energy in its high Q tank rather than in the lossy dielectric thin film. Due to the electrode assembly in the transducer, the HBAR operates in a thickness expansion-compression mode. The large volume of the resonator (mostly the substrate) makes it possible to support a dense spectrum of high Q acoustic modes. The transducer if considered as a standalone resonator will have its fundamental mode followed by its odd harmonics as shown in Fig. 1(b). The sapphire substrate on the other hand, has its fundamental mode given by \({f}_{{sub}}={v}_{{sub}}/{2t}_{{sub}}\) (v and t are acoustic velocity and thickness, respectively), which will be a few MHz. The harmonics (both even and odd) of the thick substrate is modulated by the transducer layer, with strong excitation of HBAR modes falling in regions where the transducer operate optimally as shown in Fig. 1(b) which are affected by both DC bias applied and the temperature of operation as shown in Fig. 1(d).

a Schematic of ferroelectric HBAR depicting one of the phonon modes that is excited inside the sapphire substrate through induced piezoelectric effect of BST transducer by using both DC and AC source and measured using a network analyzer. b the transducer frequency spectra (in red) with the displacement profiles of the fundamental and the third harmonics (inside the red bubble); the HBAR spectra modulated by the transducer (in blue) depict multiple modes due to standing waves inside substrate with displacement profiles of two overtone modes (inside the blue bubble). c CPW GSG probes with CS 5 substrate for standard short open load (SOL) calibration with inset showing the device under test (DUT) being probed by a 150 µm pitched GSG probe. d the BST HBAR frequency response dependency on both the temperature and DC bias applied

Experimental results and discussion

Dielectric characterization

The dielectric property of the Ba0.5Sr0.5TiO3 thin film is first characterized at an off-resonance frequency (10–500 MHz) over 10 K to 350 K temperature (without DC bias) using a network analyzer (Keysight PNA-X) and a Lakeshore probe station (CRX-4K, liquid He). The permittivity and loss tangent of the circular patch capacitor (MIM) are extracted from the scattering parameter (S11)38 and plotted in Fig. 2. In Fig. 2(a), for all the frequency under consideration, the peak of the permittivity occurs at temperature around 220 K which is identified as the phase transition temperature i.e. the ferroelectric phase to paraelectric phase of the BST thin film and the permittivity decreases with increase of frequency because of dielectric relaxation phenomenon. The dielectric loss i.e. the loss tangent increases with increasing temperature and frequency as shown in Fig. 2(b). The effect which is observed for the ferroelectric BST film with temperature can be extended with the inclusion of DC bias where the DC bias has an effect which can be thought of as changing the phase transition temperature of the material because of which the permittivity decreases with an increasing bias applied39,40,41. The resonance characteristics of the acoustic wave devices employing ferroelectrics takes advantage of the DC bias dependence controllability of its dielectric properties for achieving reconfigurability and here in this work we explore this effect in conjunction with the influence it has on the HBAR responses at cryo-temperatures.

Additionally, the use of high permittivity and tunable dielectric material in QAD circuits could be beneficial for realizing varactor as the coupling element between qubit and resonators and in enhancing electric field confinement from the qubit. Recent works have explored the use of bulk single crystal quantum paraelectric material i.e. strontium titanate and potassium tantalate for designing varactor for readout of carbon nanotube quantum dot devices at millikelvin temperatures42. The electric field dependent permittivity allows for both impedance matching and frequency tuning of resonator allowing a highly sensitive readout of solid-state quantum devices.

Resonator characterization

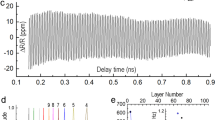

Here in this section, we present the characteristics of the HBAR with changing temperature (10 K to 300 K) and DC bias (−45 V to +45 V) conditions. Figure 3(a–d) shows the frequency spectra of the HBAR at different temperatures with a positive bias and negative bias condition, respectively. The S parameter reflection responses and the impedance characteristics of the HBAR are plotted in Figs. S1, S2 of Supplementary Material. The fundamental mode of the transducer translates as the first envelope in the spectra where the intense multimode response is observed around 2 GHz for both (+) and (–) bias conditions. The distribution of the modes in the first envelope of the HBAR response is different for the two biasing polarities where the positive bias condition excites overtone modes in the frequency range of 1 GHz to 7 GHz (L to C band) while the negative bias in the range 0.5 GHz to 5 GHz. The third harmonics of the transducer translates as the second envelope in the HBAR spectra around 8-12 GHz (X-band) with the positive bias condition while the negative bias condition presents a strong multimode response in the frequency range 6 - 10 GHz (C to X band). Significant modes are excited in the second envelope relating to the third harmonic modulation of the BST transducer in the negative bias condition compared to the positive bias condition. The variations in the envelope shape and region as shown in Fig. 3(c) between a positive and negative bias conditions might be attributed to the difference in resonance response with different bias polarity for the BST transducer and this fundamental behaviour is yet to be explored in detail. Without a DC bias no significant resonant modes are excited thereby proving the switchability and reconfigurability of the resonator response.

Since the resonator exhibits multitude of modes over a wide range, to understand the overall behaviour, it is useful to study the distributions of the effective coupling coefficient and the free spectral range (FSR) rather than focusing on one mode at a time43. The distribution of effective electromechanical coupling factor (\({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\)) for all the modes occurring in the first envelope of the spectra are plotted in Fig. 4(a, b) and for varying temperatures with +45 V and -45 V DC bias, respectively. The \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) is calculated using:

fs and fp represent series and parallel resonance frequency, respectively, while m is the mth mode under consideration. The spacing of the parallel resonance frequency (SPRF) otherwise referred to as the free spectral range (FSR) is given by:

The FSR is plotted in Fig. 4(c, d) for varying temperatures with +45 V and -45 V DC bias, respectively. Upon closer inspection, the distribution of \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) in Fig. 4(a, b) is not identical. This can be correlated with different frequency spectra for different bias polarity as shown in Fig. 3(a–c). This set of studies establishes the thin-film dominance on defining the transducer envelope and its subsequent tailoring of the high-performance phonon modes encapsulated in the sapphire substrate. The HBAR exhibits a \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) of 5.6*10-4 at 2 GHz (1st lobe of the envelope) and 2.7*10−4 at 7 GHz (2nd lobe of the envelope) at temperature 10 K with a bias of – 45 V (Fig. S3 in supplementary materials).

The resonance spectra, the distribution of \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) and the FSR offer us information about acoustic impedance characteristic of the whole resonator stack43. The acoustic impedance mismatch in the resonator stack (BST/Sapphire) is seen as the sinusoidal like distribution in FSR in contrast to an impedance matched case where the FSR distribution ideally gives a flat (straight) distribution34,35,36. The standard deviation of the FSR for an HBAR with BST/Sapphire configuration is as high as 33.6 kHz while that of an impedance matched HBAR with AlN/ SiC is 13 kHz35. Impedance matching is proven to vastly improve the performance of the resonator due to efficient energy injection from transducer to substrate34. Apart from the acoustic impedance matching for the resonator stack, a parameter which plays major role in the excitation of high Q modes is the thickness of the substrate being used. In our design we utilize a 500 µm thick sapphire, which is a major contribution to the high Q response of the HBAR. Due to the thickness effect of the substrate, the fQ reported in this work are much higher when compared to even acoustically matched HBARs with SiC substrate thicknesses of 244 µm35 and 360 µm36. The coupling coefficient for the ferroelectric HBAR discussed here show considerable improvement while decreasing the temperature and by increasing DC bias (Section S2 in Supplementary Material) which can be considered as way to efficiently inject acoustic energy from transducer to substrate. Furthermore, apart from the fQ product, the ratio of the coupling strength (between photon and phonon) to FSR in QAD systems is an important parameter deciding the multimode interactions for facilitating quantum memory operations and studying superstrong coupling regimes9.

Quality factor

In order not to overestimate the Q of the resonator, care has been taken both in the measurement procedure as well as in the post processing of the collected data from measurement by using multiple Q analysis methods. During the measurement, SOL (1-port) calibration is carried out at each temperature step of interest. And to eliminate erroneous estimation of quality factor, multiple channel calibrations for multiple windows (window span of 500 MHz with 100,000 data points) of the required frequency ranges are performed instead of performing a single calibration for the whole frequency range at once and extrapolating the calibration for narrower band. All measurements were conducted for an AC power of -5 dBm. Bias tee is included in the setup for providing the external DC bias with a power supply. No smoothing of data is done for the Q calculation. Most effort has been put forth in defining the optimal set up during measurements. To confirm the validity of the technique of Q extraction utilized in this work, two different methods of Q extractions i.e., QBode (Eq. 3) and QLakin (Eq. 4) are first employed on the highest Q mode of the resonator, one at around 5 GHz (for +45 V case) and the other at around 9 GHz (for -45 V case) for measurements performed at 10 K.

Figure 5(a, b) shows strong consistency for the utilized methods of extraction. The formulae for extraction of Q for both the methods are given below23,44:

where \(\angle Z\) is the impedance phase angle and f is the resonant (series/parallel) frequency of interest.

The modified Butterworth Van Dyke (mBVD) model and parameters extraction are listed in supplementary materials (Section S3). Figure 6(a, b) show the fQ product distributions (Q calculated using Eq. 3) for the +45 V and −45 V DC biased resonator at varying temperatures, respectively. The distribution of Q with temperature for both cases is plotted in Figure S8 of supplementary materials. The drop in the fQ or the Q at around 70 K to 130 K relates to the relaxation behaviour of the attenuation coefficient of materials45. Interestingly, similar trends are also observed in temperature-dependent loss tangent studies for sapphire27. This validates the fact that major portion of the vibrational energy is confined in the sapphire substrate.

Different DC bias polarity excites different harmonics in the transducer as discussed earlier which makes the distribution of fQ to be different for +45 V and −45 V DC. To further the argument of the functionality provided by the ferroelectric film, Fig. 7(a, b) shows the dependence of fQ on the bias magnitude applied for all the modes in the wide spectra. In Fig. 7(b), a change in DC bias from −25 V to −45 V, the fQ of 1.52 × 1015 Hz increases to 1.72 × 1015 Hz yielding a considerable 13% increase in the fQ when the mode with highest Q is considered for each biasing case. Figure 7(c, d) shows how the fQ of HBAR and hence its phonon relaxation time (in supplementary materials Section S4) is tuneable by an externally applied DC bias. The increase in the Q can be partially attributed to the enhancement in\(\,{k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) by increasing in DC bias which means that more transduction of acoustic energy to electrical energy and vice-versa is achieved through increasing magnitude of DC bias.

The Q is a measure for the total losses in the resonator. Losses in the resonators are attributed to intrinsic material losses, anchor losses, electrical losses etc. Intrinsic material losses in the device are due to three dissipation mechanisms i.e., thermoelastic dissipation, phonon-electron dissipation, and phonon-phonon dissipation. Out of these three dissipation mechanisms, since the HBAR is operated at the GHz frequency range and the resonator is mainly dominated by the insulating single crystal sapphire substrate, the phonon-phonon dissipation is the dominating loss mechanism. The study on the dependence of the Q on frequency and temperature yields information on what dissipation or damping mechanism is at play for the resonator being studied46,47,48,49,50. In the sapphire-based HBAR discussed here, the fQ distributions of the acoustic modes are affected by both temperature and frequency (shown in Fig. 8), which is explained by dissipation happening due to phonon-phonon interactions. From Figs. 6 and 8, the modes at higher frequencies (f > 4 GHz) have higher dependence on temperature compared to modes at lower frequencies (f ~ 1 GHz). At T ≤ 70 K, modes above 8 GHz show fQ above 1015 Hz meaning the phonon lifetime for the modes are a few microseconds.

Due to multiple modes falling within a wide frequency spectrum, HBAR platform facilitates the observations of gradual evolution of temperature dependence of the fQ trend in a single resonator platform51. To identify this, the phonon attenuation, α (calculated from, Q = ω/2αv where v is the phase velocity) for six different modes at frequencies 2.23 GHz, 3.82 GHz, 5.33 GHz, 6.56 GHz, 8.65 GHz, and 9.05 GHz are extracted and the temperature dependence of each mode is identified. Figure 9 shows the temperature dependence relationship of α changing from T1.48 to T4.75 as the frequency increases. The temperature and the Q-1 relationship along with the temperature dependence of frequency of the selected modes are provided in supplementary materials (Section 4). Based on these observations, the higher frequency modes are close to Landau-Rumer’s regime when operated at low temperature while the lower frequency modes are operating in-between Akhiezer’s regime and Landau-Rumer’s regime37,46,47,48,49,50,51.

From the experimental results discussed so far, it is important to draw upon the implication a ferroelectric or a paraelectric based HBAR will have upon its application into a circuit QAD system. In a hybrid quantum system, the operating frequency are decided by the type of qubit which are to be utilized, and the frequency falls in the microwave frequency range. On chip QAD systems utilizes mostly flux, phase, transmon and spin qubits3,7,52 which have operating frequencies easily achievable with mechanical resonators like SAW 4or BAW3,7. The BST HBAR presented here has a wide span of frequency range which covers frequencies which are suitable for QAD application52. The utilization of such GHz resonator is highly desirable as the quantum ground state cooling can be achieved at relatively higher temperatures while comparing it with mechanical resonators operating below 1 GHz. The reported fQ in this work are in the same order or higher when compared to other HBAR utilized for QAD while being operated at a much higher temperature relatively7,11,26. The fQ is bound to improve further if the BST HBAR is operated at millikelvin temperature where most QAD systems are implemented. The high fQ can be interpreted as having high coherent oscillations, \({N}^{({osc})}={fQh}/\,(2\pi {k}_{B}T)\), where kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is temperature and h is Planck constant. Achieving a large value of \({N}^{({osc})}\) is crucial for applications into study of quantum phenomenon. For the BST HBAR mode at 9.16 GHz (with fQ = 1.72 × 1015 Hz) measured at 10 K, the \({N}^{({osc})}\) ~ 1.3 × 103 which proves that the HBAR can be incorporated into hybrid systems like optomechanics or QAD9.

BST HBAR has the potential to further improve the performance through modification in the excitation scheme and optimization of the device stack. The ferroelectric based HBAR has an added advantage of providing reconfigurability as it is heavily influenced by both the magnitude and the polarity of the bias being applied externally. The DC bias can tune the permittivity of the BST and the HBAR as a whole show bias dependence in terms of its Q and \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\). If the BST HBAR were to be implemented into a QAD system3,7, we can expect the use of the ferroelectric film would vastly improve the coupling as DC bias can increase the \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) (Shown in Section S2 of Supplementary Material). From a plausible system point of view, this is better understood by representing a qubit coupled to the BST HBAR in an equivalent circuit shown in figure S4. The coupling strength qubit-resonator coupling strength, Ω is given by53

where, Cq,eff = Cq + C0 Cc (C0 + Cc)−1; Cq is the capacitor in parallel to the Josephson junction, C0 is the capacitance associated with the resonator’s static arm and Cc is capacitor which couples the resonator with a qubit. Based on the above equation and several other definitions relating coupling between qubit and mechanical resonator, we can see how the resonator’s parameters can affect the coupling strength. Since the motional arm elements are dependent on \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) of the resonator, having a controllable \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) provide flexibility in tuning the coupling strength dynamically. This is crucial, as there is a trade-off between Q and \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\), and the only way to adjust this for a piezoelectric HBAR is by thinning down the substrate which increases \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) while degrading the Q, or vice versa. For the on-chip application, the voltage dependent capacitor (BST varactor) could provide vital tuning parameter for getting an optimal coupling strength. Such controllability could also provide an option to switch between a strong or weak coupling regimes depending on the application targeted. With the BST HBAR’s ability to provide coherent and long phonon lifetime, it is worthwhile to explore its potential in the field of hybrid quantum systems.

Conclusion

DC-field induced piezoelectricity in BST is explored to realize a phonon source that exhibit high fQ product multimode response at the GHz frequencies covering L to X band at cryogenic temperature where most qubits operate. Additionally, the unique switchability and tuneability feature that BST offers in the frequency and temperature range makes this an excellent platform for QAD applications. The work reported here showed the effect of DC biasing and temperature on the resonator parameters i.e. FSR, \({k}_{{eff}}^{2}\) and fQ. The highest loaded Q of 180,000 at 9.15 GHz at 10 K is recorded for the HBAR with a DC bias of -45 V. Additionally, a very close match between measurement and electromechanical model is achieved for phonon modes in the GHz operating under different biases and temperatures. The ferroelectric based HBAR demonstrated in this work exhibits the highest fQ product achieved using polycrystalline ferroelectric thin films. The use of ferroelectric HBAR in hybrid quantum systems like QAD has not been explored yet, and the result presented here shows that the high permittivity (with tuning capability) of such materials could be advantageous in being an excellent switchable phonon source and to realize a tuneable microwave resonator for coupling (or readout) with qubit (s).

References

Wallraff, A. et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 431, 162–167 (2004).

Clerk, A. A. et al. Hybrid quantum systems with circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nat. Phys. 16, 257–267 (2020).

O’Connell, A. et al. Quantum ground state and single-phonon control of a mechanical resonator. Nature 464, 697–703 (2010).

Andersson, G. et al. Squeezing and multimode entanglement of surface acoustic wave phonons. PRX Quantum 3, 010312 (2022).

Wollack, E. A. et al. Quantum state preparation and tomography of entangled mechanical resonators. Nature 604, 463–467 (2022).

Kitzman, J. M. et al. Phononic bath engineering of a superconducting qubit. Nat. Commun. 14, 3910 (2023).

Yiwen, C. et al. Quantum acoustics with superconducting qubits. Science 358, 199–202 (2017).

MacCabe, G. S. et al. Nano-acoustic resonator with ultralong phonon lifetime. Science 370, 840–843 (2020).

Han, X., Zou, C. L. & Tang, H. X. Multimode strong coupling in superconducting cavity piezo electromechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 123603 (2016).

Safavi-Naeini, A. H., Van Thourhout, D., Baets, R. & Van Laer, R. Controlling phonons and photons at the wavelength scale: integrated photonics meets integrated phononics. Optica 6, 213–232 (2019).

Kervinen, M., Rissanen, I. & Sillanpää, M. Interfacing planar superconducting qubits with high overtone bulk acoustic phonons. Phys. Rev. B 97, 205443 (2018).

Hagelauer, A. et al. From microwave acoustic filters to millimeter-wave operation and new applications. IEEE J. Microw. 3, 484–508 (2023).

Hashimoto, K. Y. RF bulk acoustic wave filters for communications. (Artech House, 2009).

Zhao, X., Zhao, M., Peng, W. & He, Y. Review of bulk acoustic wave resonant optical detectors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 355, 114333 (2023).

Vetury, R. et al. A Manufacturable AlScN Periodically Polarized Piezoelectric Film Bulk Acoustic Wave Resonator (AlScN P3F BAW) Operating in Overtone Mode at X and Ku Band. In 2023 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium (IMS), 891–894 (IEEE, 2023).

Gokhale, V.J. Roussos, J.A. Hardy, M.T. Katzer, D.S. & Downey, B.P. Room Temperature Nanophononics from 1 GHz–110 GHz with Composite Piezoelectric Transducer HBARs. In IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), 1087–1090 (IEEE, 2024).

Tian, H. et al. Hybrid integrated photonics using bulk acoustic resonators. Nat. Commun. 11, 3073 (2020).

Dietz, J. R. et al. Spin-acoustic control of silicon vacancies in 4H silicon carbide. Nat. Electron 6, 739–745 (2023).

Warder, P. & Link, A. Golden age for filter design: innovative and proven approaches for acoustic filter, duplexer, and multiplexer design. IEEE Microw. Mag. 16, 60–72 (2015).

Wu, H., Wu, Y., Lai, Z., Wang, W. & Yang, Q. A hybrid filter with extremely wide bandwidth and high selectivity using FBAR network. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs 69, 3164–3168 (2022).

Sliker, T. R. & Roberts, D. A. A thin-film CdS-quartz composite resonator. J. Appl. Phys. 38, 2350–2358 (1967).

Moore, R. A., Haynes, J. T. & McAvoy, B. R. High overtone bulk resonator stabilized microwave sources. In Ultrasonics Symposium 414–424 (IEEE, 1981).

Lakin, K. M., Kline, G. R. & McCarron, K. T. High-Q microwave acoustic resonators and filters. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 41, 2139–2146 (1993).

Gong, S. & Piazza, G. Design and analysis of lithium–niobate-based high electromechanical coupling RF-MEMS resonators for wideband filtering. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 61, 403–414 (2012).

Von Lüpke, U. et al. Engineering multimode interactions in circuit quantum acoustodynamics. Nat. Phys. 20, 564–570 (2024).

Crump, W., Välimaa, A. & Sillanpää, M. A. Coupling high-overtone bulk acoustic wave resonators via superconducting qubits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123 (2023)

Setter, N.et al. Ferroelectric thin films: Review of materials, properties, and applications. J. Appl. Phys. 100 (2006)

Vorobiev, A., Rundqvist, P., Khamchane, K. & Gevorgian, S. Silicon substrate integrated high Q-factor parallel-plate ferroelectric varactors for microwave/millimeterwave applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 83, 3144–3146 (2003).

Bouça, P. et al. Reconfigurable three functional dimension single and dual-band SDR front-ends using thin film BST-based varactors. IEEE Access 10, 4125–4136 (2022).

Nam, S., Koohi, M. Z., Peng, W. & Mortazawi, A. A switchless quad band filter bank based on ferroelectric BST FBARs. IEEE Microw. Wirel. Compon. Lett. 31, 662–665 (2021).

Kongbrailatpam, S., Akhil, T. S., Chandrashekar, L. N., James Raju, K. C. & Gayathri P. Laterally Coupled BST/Sapphire High Overtone Bulk Acoustic Resonators Exhibiting DC Tunable Comb Filter Response with High Qf Product. In Joint Conference of the European Frequency and Time Forum and IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium (EFTF/IFCS), 1–3 (IEEE, 2023).

Sandeep, K., Pundareekam Goud, J. & James Raju, K. C. Resonant spectrum method for characterizing Ba0. 5Sr0. 5TiO3 based high overtone bulk acoustic wave resonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 012901 (2017).

Kongbrailatpam, S., Akhil, T. S., Chandrashekar, L. N., James Raju, K. C. & Gayathri P. Temperature and Bias-Dependent Switchability and Tuneability of Very High-Quality Factor GHz Resonators. In IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), 148–151 (IEEE, 2024).

Gokhale, V. J. et al. Epitaxial bulk acoustic wave resonators as highly coherent multi-phonon sources for quantum acoustodynamics. Nat. Commun. 11, 2314 (2020).

Kurosu, M. et al. Impedance-matched high-overtone bulk acoustic resonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122 (2023).

Cheng, J., Peng, Z., Zhang, W. & Shao, L. Metal-free high-overtone bulk acoustic resonators with outstanding acoustic match and thermal stability. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 44, 1877–1880 (2023).

Braginsky, V. B., Ilchenko, V. S. & Bagdassarov, K. S. Experimental observation of fundamental microwave absorption in high-quality dielectric crystals. Phys. Lett. A 120, 300–305 (1987).

Ma, Z. et al. RF measurement technique for characterizing thin dielectric films. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 45, 1811–1816 (1998).

Tagantsev, A. K., Sherman, V. O., Astafiev, K. F., Venkatesh, J. & Setter, N. Ferroelectric materials for microwave tunable applications. J. Electroceram. 11, 5–66 (2003).

Garten, L. M. et al. Relaxor ferroelectric behavior in barium strontium titanate. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 99, 1645–1650 (2016).

Zhang, M., Zhai, J., Xin, L. & Yao, X. Effect of biased electric field on the properties of ferroelectric-dielectric composite ceramics with different phase-distribution patterns. Mater. Chem. Phys. 197, 36–46 (2017).

Apostolidis, P. et al. Quantum paraelectric varactors for radiofrequency measurements at millikelvin temperatures. Nat. Electron 7, 760–767 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Wang, Z. & Cheeke, J. D. N. Resonant spectrum method to characterize piezoelectric films in composite resonators. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 50, 321–333 (2003).

Feld, D. A., Parker, R., Ruby, R., Bradley, P. & Dong, S. After 60 years: a new formula for computing quality factor is warranted. In IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, 431−436 (IEEE, 2008).

Auld, B. A. Acoustic fields and waves in solids. (Рипол Классик, 1973).

Chandorkar, S. A. et al. Limits of quality factor in bulk-mode micromechanical resonators. In IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems, 74−77 (IEEE, 2008).

Tabrizian, R., Rais-Zadeh, M., & Ayazi, F. Effect of phonon interactions on limiting the fQ product of micromechanical resonators. In TRANSDUCERS International Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Conference, 2131−2134 (IEEE, 2009).

Goryachev, M. et al. Recent investigations on BAW resonators at cryogenic temperatures. In Joint Conference of the IEEE International Frequency Control and the European Frequency and Time Forum (FCS), 1−6 (IEEE, 2011).

El Habti, A. & Bastien, F. O. Low temperature limitation on the quality factor of quartz resonators. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Frequency Control 41, 250–255 (1994).

De Klerk, J. Behavior of coherent microwave phonons at low temperatures in Al2O3 using vapor-deposited thin-film piezoelectric transducers. Phys. Rev. 139, 5A (1965).

Gokhale, V. J. et al. Temperature evolution of frequency and anharmonic phonon loss for multi-mode epitaxial HBARs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 124003 (2020).

Schoelkopf, R. & Girvin, S. Wiring up quantum systems. Nature 451, 664–669 (2008).

O’Connell, A. D. A macroscopic mechanical resonator operated in the quantum limit. Ph.D. thesis, University of California (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) through the IoE PDF fellowship and the Department of Science & Technology (DST) under Grant No. DST/TDT/AM/2022/084. The authors would like to thank the National Nanofabrication Centre (NNFC) for the fabrication facilityand the Micro Nano Characterisation Facility (MNCF). Authors from University of Hyderabad acknowledge the fund provided by DST-SERB (GrantNumber: CRG/2019/000427) and MHRD (Grant Number: UoH-IoE F11/9/2019-U3(A)) at the University of Hyderabad. K. C. James Raju acknowledgesthe Abdul Kalam Technology Innovation National Fellowship (INAE/121/AKF/29) awarded to him.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kongbrailatpam, S.S., T S, A.R., K C, J.R. et al. Switchable and tuneable high-performance acoustic modes in the L-X band using ferroelectric thin film on sapphire. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 217 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01080-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01080-5