Abstract

Metal oxide semiconductor gas sensors exhibit significant advantages in gas detection due to their high sensitivity and low cost. However, challenges such as poor selectivity and insufficient stability remain critical scientific issues. In this study, tin dioxide nanomaterials with a unique structure were successfully synthesized using ZIF-8 as a template. Further modification with gold-decorated reduced graphene oxide yielded a nanocomposite that demonstrated rapid response, high sensitivity, and excellent selectivity for low-concentration ethylene detection. The crystal structure, morphology, elemental composition, and pore size distribution of the materials were systematically characterized using XRD, FESEM, EDS, UV-Vis spectroscopy, and N2 adsorption-desorption analysis. Gas sensing tests revealed that the sensor exhibited a response value of 5.35 to 20 ppm C2H4 at an optimal operating temperature of 280 °C, with response and recovery times of 14 s and 17 s, respectively. The selectivity ratio for ethylene over the second most sensitive gas was 3.26, highlighting its superior specificity. Additionally, the sensor demonstrated good stability and repeatability, providing a cost-effective solution for real-time ethylene monitoring in humid environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethylene (C2H4) plays a pivotal role in industrial and agricultural sectors, serving as a critical raw material in polymerization processes, plastics production, and fruit ripening regulation1,2. Its precise detection is essential for optimizing industrial efficiency, ensuring agricultural product quality, and mitigating safety risks due to its flammability3.

Tin dioxide (SnO2), a widely studied n-type semiconductor with a bandgap of 3.6 eV, has been extensively explored for gas sensing owing to its chemical stability, high electron mobility, and low fabrication cost4. For example, Pil Gyu Choi et al.5 synthesized SnO2 nanosheets with remarkable selectivity towards olefin gases (C2H4, C3H6, C4H8), and higher response values than those of alkane gases (CH4, C2H6, C3H8, n-C4H10).

Despite the fact that pure SnO2 gas sensors are sensitive to a variety of gases, but generally poor in terms of selectivity as well as response and high relative operating temperature6,7. To address these limitations, strategies such as noble metal doping, heterojunction construction, and morphological engineering have been employed to enhance sensor performance8. Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) has an atomic-level thickness that endows the material with an extremely high specific surface area9. Meanwhile, the abundant surface defects and oxygen-containing functional groups enable it to form strong interactions with metal oxide semiconductor materials, thereby generating a synergistic effect within the composite material system10. This synergistic effect not only contributes to the improvement of the electrical properties of the material but also significantly enhances its adsorption and reaction activity towards target gases, thus effectively enhancing the gas sensing performance of the sensor. For instance, Jiang et al.11 reported that SnO2/NiO/rGO ternary composites exhibited a 21.11 response to 50 ppm acetone at 350 °C, with a response time of 5 s. Compared with SnO2/NiO, SnO2/NiO/rGO significant improvements in response speed and sensitivity are exhibited.

Gold nanoparticles (Au NPs), known for their catalytic activity and π-electron interactions with C2H4, further enhance sensitivity by lowering the activation energy for C2H4 oxidation12. When Au exists in the form of nanoparticles, the coordination unsaturation of surface atoms increases, generating abundant active sites. These active sites can adsorb C2H4 molecules, inducing a certain degree of distortion and polarization of their carbon-carbon double bonds, thereby reducing the activation energy for C2H4 molecules to participate in redox reactions and promoting reaction progression13. Shiva et al.14 investigated the gas-sensing properties of 0.5 wt% Au-doped SnO2 thick-film sensors toward n-butanol. The test results revealed that Au significantly altered the operating temperature and substantially enhanced the response level of the gas sensor. Compared with pure SnO2, the Au/SnO2 sensor exhibited a 70 °C reduction in operating temperature and a 4-fold increase in response. Studies indicate that upon metal doping, a depletion layer forms on the surface of metal oxide particles, altering the surface potential of SnO2. The increased potential barrier ultimately improves the sensing performance.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are formed through the coordination-driven self-assembly of inorganic metal nodes and organic ligands. These architectures exhibit distinctive advantages including structural diversity, high hydrophobicity, exceptional porosity, and tunable pore dimensions15,16. Such characteristics confer exceptional application potential in gas adsorption, separation, and sensing applications, establishing MOFs as prominent research foci in contemporary materials science. In a representative study, Homayoonnia Setareh17 synthesized a ZIF-8/MWCNT-coated sensor demonstrating exceptional acetone responsiveness. This sensor exhibited minimal humidity interference, high selectivity, excellent repeatability, complete reversibility and rapid response kinetics. Notably, it achieved a detection limit (LOD) of 1.7 ppb at 25 °C.

Against the aforementioned research background, this study innovatively proposes and fabricates the Au-rGO/ZIF8-SnO2 composite material, aiming to integrate the high electrical conductivity and surface activity of rGO, the molecular sieve effect of ZIF-8, and the gas-sensing properties of SnO2 to construct a novel high-performance C2H4 gas sensor. Using advanced material characterization techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and nitrogen adsorption-desorption, a comprehensive and in-depth analysis and characterization of the crystal structure, microstructure, and pore size distribution of the Au-rGO/ZIF8-SnO2 composite material was conducted.

Experimental

All reagents used were of analytical grade, purchased from Sinopharm Group, and used without further purification.

Synthesis of ZIF-8

ZIF-8 was synthesized using Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O as the zinc source and 2-methylimidazole as the ligand. Briefly, 0.594 g of Zn(CH3COO)2·2H2O and 1.313 g of 2-methylimidazole were separately dissolved in 50 mL of methanol under continuous stirring. The two solutions were mixed and stirred for 30 min to form a white turbid suspension. Then transferred into a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 120 °C for 24 h. The product was centrifuged at 4000 rpm, washed three times with methanol, and dried at 60 °C under vacuum for 12 h to obtain ZIF-8 nanopowder.

Synthesis of Au-GO

Au nanoparticles (NPs) were synthesized by dissolving 20 mg of HAuCl4·3H2O in 50 mL of deionized water (DI) under reflux at 115 °C for 15 min. A solution of 147 mg trisodium citrate dihydrate (C6H5Na3O7·2H2O) in 10 mL DI was slowly added to the refluxing solution, which turned from gray to purple and finally wine-red. After cooling, 200 mg of graphene oxide (GO) was dispersed in 140 mL DI via 90 W ultrasonication for 1 h. The Au colloid was mixed with the GO dispersion, stirred at 95 °C for 24 h, centrifuged at 15,000 rpm, washed with ethanol and DI, and dried at 75 °C to yield Au-rGO.

Synthesis of Au-GO/ZIF8-SnO2

0.226 g SnCl2·2H₂O and 0.3 g urea were dissolved in 50 mL ethylene glycol. The pre-prepared 0.5 g of ZIF-8 powder was added to the solution, followed by 3 h of ultrasonic dispersion to ensure complete dissolution of the ZIF-8 powder. A certain amount of Au-rGO powder was then added, followed by an additional 1 h of ultrasonication. The mixture was hydrothermally treated at 150 °C for 12 h, washed with DI and ethanol, dried at 60 °C, and calcined at 600 °C (2 °C/min) for 3 h. The final products, labeled ZIF-8/SnO₂, NG1 (1 at% Au-rGO), and NG2 (1.5 at% Au-rGO), were obtained.

The synthesis schematic is shown in Fig. 1.

Gas sensor fabrication

The MEMS sensor is a cuboid with dimensions of 4 × 4 × 1 mm. There are pads on the bottom surface for soldering to the sensor signal acquisition circuit, the temperature-voltage curves presented in the Fig. 2 below. Material was prepared with ethanol and the adhesive aluminum silicate to form a slurry. The prepared slurry is applied to the interdigital electrodes of the micro hot plate to make a gas sensor. Finally, the gas sensor sample was maintained at an external heating voltage of 2.0 V for 72 h.

Synthetic air (21% O2, 79% N2) was used as the carrier gas, and different concentrations of C2H4 were configured by a gas dilution instrument, and the output port of the gas dilution meter was connected to the gas input port of our self-designed gas chamber. The gas flow continued to flow throughout the experiment.

Results and discussion

Material characterization

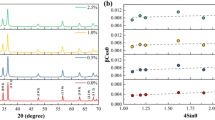

The XRD test was carried out using a Bruker D8 Advance instrument. Wide-angle diffraction tests were performed on the sample materials, and the test lasted for 10 minutes. The spectra are shown in Fig. 3.

The results in Fig. 3 indicate that all diffraction peaks of the prepared ZIF8-SnO2 sample are indexed to ZnO (PDF#36-1451) and SnO2 (PDF#41-1445), demonstrating the hexagonal polycrystalline structure of the as-prepared sample. The diffraction peaks at 2θ = 38.25° and 44.46° match well with the characteristic peaks of the (111) and (200) crystal planes of the Au standard card (PDF#99-0056). The XRD results demonstrate that the prepared nanomaterials contain ZIF-8 and SnO2, with successful doping of Au.

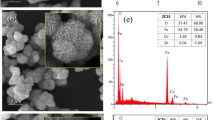

In this study, FESEM characterization was performed using GeminSEM, with images of ZIF-8, ZIF8-SnO2, NG1, and NG2 shown in Fig. 4(a, b, c, d). Figure 4e, present the EDS images and quantitative data of NG1 and NG2 Fig. 4. FESEM images reveal that the prepared ZIF-8 exhibits a rhombic dodecahedral morphology with good symmetry, measuring approximately 0.8 μm in size. Figure 4b shows that ZIF8-SnO2 consists of numerous SnO2 nanoparticles attached to the ZIF-8 surface, forming gas diffusion channels between particles. The SnO2 nanoparticles have a diameter of 10–20 nm. FESEM images of NG1 and NG2 Fig. 4c, d demonstrate that ZIF8-SnO2 nanoparticles are anchored onto the surface of Au-GO nanosheets, with further reduced particle size.

EDS elemental decomposition results confirm the presence of SnO2, ZIF-8, and Au in the nanocomposites, with the atomic percentage of Au varying with doping concentration. These results verify that Au-GO has been successfully modified onto the nanoparticle surface, forming a heterostructural architecture.

We conducted TEM and HRTEM characterization of the Au-GO sample using an FEI Tecnai G2 F30 field-emission transmission electron microscope. Figure 5a is TEM image of Au-GO, reveals that the synthesized GO exhibits a film-like multilayer structure. Gold nanoparticles with diameters of approximately 10–20 nm are attached to its surface, and most of these particles are uniformly distributed on the GO surface with minimal aggregation. Clear lattice fringes belonging to the Au nanoparticles were observed in the HRTEM image Fig. 5b.

Raman spectroscopy characterization of GO and Au-GO nanomaterials was performed using a 514 nm laser as the excitation source, with the results shown in the Fig. 6. As can be observed, both GO and Au-GO exhibit three main characteristic peaks corresponding to the D band, G band, and G’ band of graphene. The ID/IG ratio for GO is 1.04. After doping with Au nanoparticles, the ID/IG ratio of Au-GO increases to 1.11, indicating that the incorporation of Au nanoparticles introduces a higher density of structural defects into the GO framework.

We measured the UV–Vis absorption spectra and energy band gaps of ZIF8-SnO2 and NG2 using UV - 3600 UV–Vis–NIR spectrophotometer. Figure 7a displays the UV-Vis absorption spectra of the two materials. The band gaps were calculated using the Tauc Plot method based on the absorption spectra. Results show that the band gaps of ZIF8-SnO2 and NG2 are 3.19 eV and 2.79 eV, respectively. The narrowing of the band gap after Au-GO doping is attributed to the increased oxygen vacancy concentration. As oxygen vacancies act as donor defects, their presence shifts the Fermi level of the oxide upward, creating defect energy levels within the band gap and thus reducing the band gap. Additionally, the narrower band gap indicates that electrons in NG2 can more easily transition from the valence band to the conduction band, which enhances the sensitivity of the gas-sensing material toward target gases—a finding consistent with the gas-sensing performance test results of the sensor.

Specific surface area of metal oxide semiconductors significantly affects the adsorption and desorption capacities of target gases. So we investigated the pore size distribution and specific surface area of ZIF8- SnO2 and NG2, we conducted nitrogen adsorption - desorption measurements using Micromeritics ASAP 2460. The result is shown in Fig. 8.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of ZIF8-SnO2 and NG2 demonstrate that both samples exhibit Type IV isotherms with H3-type mesoporous hysteresis loops appearing at relative pressures (P/P0) of 0.5–0.9, indicating that the pore structure of the synthesized materials consists of slit pores formed by the accumulation of numerous particles—a finding consistent with SEM characterization results. Using the BET adsorption isotherm equation, the BET specific surface areas of ZIF8-SnO2 and NG2 were calculated to be 12.57 m2/g and 111.17 m2/g, respectively. These results reveal that Au-GO doping significantly enhances the specific surface area and pore size, which provides abundant active centers for oxygen adsorption and chemical reactions with analytes, thereby improving the gas-sensing properties of the sensor.

In situ XPS characterization of the material was performed, with the survey spectrum shown in Fig. 9a confirming the presence of five elements: Zn, Sn, C, O, and Au. Fig. 9b displays the Au 4f spectra of the NG2 material under clean air versus C2H4 gas exposure. A positive shift of approximately 0.3–0.4 eV in the Au 4f binding energy is observed upon C2H4 introduction, indicating altered electronic states at the gold surface. This observation indicates electron donation from Au d-orbitals to the π* antibonding orbitals of adsorbed C2H4 molecules, resulting in an increased effective oxidation state of gold that elevates the core-level binding energy. Figure 9c, d present the high-resolution O 1s spectra of ZIF-8/SnO2 and NG2, respectively. Both spectra were deconvoluted into three Gaussian components corresponding to: lattice oxygen (OL), oxygen vacancies (OV) and adsorbed oxygen (OC). The proportion of OC in NG2 significantly increases, proving that after doping, the material's adsorption capacity for oxygen is enhanced. Additionally, the increased proportions of OV and OC demonstrate that NG2 possesses more defects and stronger capability to adsorb ionic oxygen, leading to band gap narrowing. This occurs because oxygen vacancies belong to donor defects, whose presence causes the Fermi level of the oxide to shift upward, introduces defect levels within the band gap, and consequently reduces the band gap.

Gas-sensing properties

We test the gas sensing performance based on the prepared materials toward C2H4. Prior to conducting other gas sensing experiments, the optimal operating temperature of the sensor was prioritized. Therefore, the response curves of gas sensors based on three nanomaterials (ZIF8-SnO2, NG1, and NG2) to 50 ppm C2H4 gas were first measured within the temperature range of 160 °C to 360 °C, with results shown in the Fig. 10.

In terms of response sensitivity, at the same operating temperature and for the same concentration of C2H4, the NG2 sensor exhibits a higher response value, while the undoped ZIF8-SnO2 sensor shows the lowest response and does not reach its optimal operating temperature within this temperature range. From the trend of temperature characteristic curves, the response curves of NG1 and NG2 sensors to C2H4 gas both exhibit a mountain-shaped profile: the response value increases with temperature rise, reaches a peak at the optimal operating temperature, and then decreases with further temperature increase. Notably, the optimal operating temperature of the high-doping NG2 sensor is lower than that of the low-doping NG1 sensor. Considering power consumption, subsequent tests were conducted at 280 °C with NG2 sensor.

Figure 11a shows the dynamic response-recovery transient curves of ZIF8-SnO2, NG1, and NG2 sensors to 1–50 ppm C2H4 gas at an operating temperature of 280 °C. Figure 11b presents the linear relationship between the response value (S) of the NG2 sensor and lgC. The response value was calculated as Ra/Rg, where Ra is the sensor resistance in air and Rg is the resistance in the test gas, with C representing the gas concentration.

As observed, the responses of NG1 and NG2 gas sensors increase with rising C2H4 concentration, while the undoped ZIF8-SnO2 sensor exhibits insignificant response due to not reaching its optimal operating temperature. Notably, Au-GO modification significantly improves sensor performance, with NG2 demonstrating the highest response value. Fitting the dynamic response curve of NG2 to C2H4 concentration yields a linear relationship: S = 4.25359lgC + 0.26533 (R2 = 0.94006). A favorable linear correlation is observed between the sensor response values and C₂H₄ concentrations.

To investigate the response/recovery time characteristics of the NG2 sensor, its response and recovery to 20 ppm C2H4 were measured at an operating temperature of 280 °C, with results shown in Fig. 12. The response time and recovery time are defined as the time required for the sensor response to change from the initial state to 90% of the steady-state value. Results demonstrate that the NG2 sensor exhibits extremely rapid response and recovery times of 14 s and 17 s, respectively.

Figure 13 presents the response of the NG2 sensor to six gases at the same concentration (50 ppm): C2H4, methane (CH4), ethane (C2H6), formaldehyde (HCHO), carbon monoxide (CO), and hydrogen (H2). The sensor exhibits superior selectivity toward C2H4, with a response value 3.26 times higher than that of the second-highest responding gas (H2).

Response of the sensor to 20 ppm C2H4 under different humidity was tested. The sensor resistance value and the response value are shown in the figure. Elevated relative humidity induces a decrease in sensor resistance, attributed to the formation of a conductive layer by adsorbed H2O molecules on the material surface. Furthermore, competitive adsorption occurs at active sites on the sensing material: H2O molecules compete with target gas molecules for adsorption sites, reducing the probability of target gas adsorption. Water molecules preferentially adsorb and form hydroxyl groups, occupying surface active centers. This competitive adsorption mechanism, consistent with the Langmuir adsorption model, results in reduced material responsiveness Fig. 14.

In terms of repeatability, the sensor was exposed to 50 ppm C2H4 gas for 7 consecutive cyclic tests as Fig. 15. The resistance of the NG2 sensor recovered to its initial state in each cycle, and the response-recovery characteristic curves of the 7 tests remained essentially consistent—demonstrating the excellent reproducibility of the NG2 sensor.

The long-term stability of the sensor is another indispensable factor of practical application, so a study on the long-term stability of the NG2 sensor was conducted, as plotted in Fig. 16. The response of the sensor to 50 ppm C2H4 was measured over 20 days. Keep the sensor powered on for 20 days, testing at the same time every day. As shown by the results, the sensor was stable and exhibited only a very small decrease in response within 20 days.

We summarized the optimal gas sensing performance of the NG2 nanocomposite-based sensor and compared it with the reported MEMS C2H4 gas sensors in recent literature, as shown in the table. The table indicates that the gas sensor fabricated in this study exhibits favorable performance in terms of operating temperature, sensitivity, detection limit, and response/recovery time. The synthesized gas sensor holds potential application value for low-concentration C2H4 detection Table 1.

Sensing mechanism of the nanocomposites of Au-GO/Co-ZnO

The Au-GO/ZIF8-SnO2 composite exhibits n-type semiconductor gas-sensing characteristics. Consistent with the general gas-sensing mechanism of n-type semiconductors, its widely accepted gas-sensing mechanism follows the gas adsorption-desorption models chematically depicted in Fig. 12. At the operating temperature of 280 °C, O2 molecules act as electron acceptors, capturing free electrons from the conduction band of SnO2 with the promotion of Au nanoparticles to form chemisorbed oxygen species (O2⁻ and O⁻). During this process, the reduction of electrons in the material's conduction band leads to an increase in material resistance. Upon exposed to C2H4 gas, as shown in Eq. 1, C2H4 molecules react with the adsorbed oxygen species on the material surface, oxidizing into CO₂ and releasing abundant electrons. These electrons return to the conduction band, manifesting macroscopically as decreased resistance Fig. 17

The introduction of Au-GO significantly enhances the gas-sensing performance of the sensor, play the critical role in sensitizing the sensing material. The surface catalytic activity of Au NPs notably reduces the activation energy barrier for C2H4 oxidation reaction, releasing abundant electrons and lowering the operating temperature required for C2H4 gas reactions on the material surface—thereby improving sensor sensitivity. Furthermore, the d-band center of Au (≈−2.8 eV) matches the energy level of the C2H4 π* orbitals (LUMO≈−3.1 eV), forming strong hybridization that selectively adsorbs C2H4 and enhances sensor selectivity. Furthermore, BET calculations reveal that NG2 exhibits a significantly larger specific surface area compared to ZIF8-SnO2. The excellent electrical conductivity of graphene accelerates gas adsorption/desorption and electron transport rates, further enhancing sensor sensitivity. Finally, the introduction of Au-GO forms a heterojunction, strengthening the electronic sensitization of the nanomaterial. As a p-type semiconductor (Au-GO) and n-type semiconductor (SnO2) reach equilibrium, the electron depletion layer at the heterojunction interface expands, facilitating additional modulation of sensor resistance and improving gas-sensing performance. Moreover, Au-GO doping narrows the band gap of SnO2, enabling easier electron transitions from the valence band to the conduction band and boosting the sensor’s gas-sensing performance.

Conclusion

In this study, Au-GO-doped ZIF8-SnO2 nanomaterials NG1 and NG2 were successfully prepared and applied as sensitive materials for C2H4 sensors. Their physical and electrical properties are compared in Table 2.

The 1.5 at% Au-GO-doped sample (NG2) demonstrated a response value of 8.24 toward 50 ppm C2H4 at 280 °C, showcasing excellent linearity within the 1–50 ppm testing concentration range. Notably, the sensor exhibited remarkable stability, outstanding reproducibility, short response/recovery times, and superior selectivity for C2H4 detection. This study provides a novel approach and new insights for highly sensitive and low-detection-limit detection of C2H4.

References

Nyhus, A. H. et al. Green ethylene production in the UK by 2035: a techno-economic assessment. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 1931–1949 (2024).

Delikonstantis, E., Fabio, C. & Stefanidis, G. D. Electrified chemical reactors for methane-to-ethylene conversion. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 41, 100927 (2023).

Iqbal, N. et al. Ethylene role in plant growth, development and senescence. Interaction with other phytohormones. Front. Plant Sci. 8, (2017).

Maheswari, S. et al. Enhanced room-temperature ammonia vapor-sensing activity of nebulizer spray pyrolysis fabricated SnO 2 thin films: an effect of Er doping. J. Mater. Res. 36, 657–667 (2021).

Choi, P. G. et al. SnO2 nanosheets for selective alkene gas sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 1820–1827 (2019).

Xue, D. Hydrothermal synthesis of CeO2-SnO2 nanoflowers for improving triethylamine gas sensing property. Nanomaterials 8, 1025 (2018).

Xue, D. Hydrothermally prepared porous 3D SnO2 microstructures for methane sensing at lower operating temperature. Mater. Lett. 237, 336–339 (2019).

Qin, S. et al. Novel ultrathin mesoporous ZnO-SnO2 nn heterojunction nanosheets with high sensitivity to ethanol. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 309, 127801 (2020).

Zhang, T. et al. Facile strategy to synthesize porous GO/ZnO heterostructure for enhanced acetone gas sensing properties. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 359, 131601 (2022).

Balakrishnan, T. et al. Recent progress on functionalized graphene quantum dots and their nanocomposites for enhanced gas sensing applications. Nanomaterials 14, 11 (2023).

Jiang, L. et al. Preparation and gas-sensing performance of GO/SnO2/NiO gas-sensitive composite materials. Ceram. Int. 47, 7528–7538 (2021).

Nakaya, Y. et al. Interstitial carbon dopant in palladium–gold alloy boosting the catalytic performance in vinyl acetate monomer synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2985–2998 (2023).

Pan, A. et al. Core–shell Au@ SnO2 nanostructures supported on Na2Ti4O9 nanobelts as a highly active and deactivation-resistant catalyst toward selective nitroaromatics reduction. Inorg. Chem. 58, 11164–11171 (2019).

Mohammad-Yousefi, S. et al. Describing the effect of Ag/Au modification on operating temperature and gas sensing properties of thick film SnO2 gas sensors by gas diffusion theory. Mater. Chem. Phys. 227, 148–156 (2019).

Ding, M., Xuechao, C. & Hai-Long, J. Improving MOF stability: approaches and applications. Chem. Sci. 10, 10209–10230 (2019).

Cravillon, J. et al. Rapid room-temperature synthesis and characterization of nanocrystals of a prototypical zeolitic imidazolate framework. Chem. Mater. 21, 1410–1412 (2009).

Homayoonnia, S. et al. ZIF-8/MWCNT-nanocomposite based-resistive sensor for highly selective detection of acetone in parts-per-billion: potential noninvasive diagnosis of diabetes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 393, 134197 (2023).

Jin, W. et al. SnO2 quantum dots-functionalized MoO3 nanobelts for high-selectivity ethylene sensing. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 10485–10494 (2022).

Zhao, Q. et al. High performance ethylene sensor based on palladium-loaded tin oxide: Application in fruit quality detection. Chin. Chem. Lett. 31, 2045–2049 (2020).

Akhir, M. A. M. et al. Ethylene gas sensing properties of tin oxide nanowires synthesized via CVD method. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 318. (IOP Publishing, 2018).

Yusefi, H. et al. A novel impedimetric ethylene gas sensor based on copper foam/CuO/SnO2 nanocomposite. J. Electrochem. Soc. 171, 097512 (2024).

Leangtanom, P. et al. Highly sensitive and selective ethylene gas sensors based on CeOx-SnO2 nanocomposites prepared by a Co-precipitation method. Mater. Chem. Phys. 254, 123540 (2020).

Ahn, H. et al. Effect of annealing and argon-to-oxygen ratio on sputtered SnO2 thin film sensor for ethylene gas detection. Mater. Chem. Phys. 124, 563–568 (2010).

Jadsadapattarakul, D. et al. Improved selectivity, response time and recovery time by [0 1 0] highly preferred-orientation silicalite-1 layer coated on SnO2 thin film sensor for selective ethylene gas detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 144, 73–80 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation of China Project (grant number 62174163).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, T., Sun, J., Qi, Z. et al. ZIF-8/SnO2 based high sensitivity ethylene gas sensor with Au-GO doped. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 14 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01081-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01081-4