Abstract

Flexible humidity sensors, as pivotal sensing components in the Internet of Things and intelligent era, have achieved significant progress in material innovation, fabrication engineering, and application diversification in recent years. This review systematically presents the current research status of flexible humidity sensors, focusing on the influence of novel humidity-sensitive materials(including polymers, metal oxides, carbon-based materials, and two-dimensional materials) on key performance metrics such as sensitivity, response time, and stability. The optimization effects of fabrication technologies such as screen printing, spraying, and deposition on device performance are also analyzed. Furthermore, the innovative applications of flexible humidity sensors in fields including healthcare, smart agriculture, smart homes, and human-machine interaction are elaborated in detail. These applications highlight the sensors’ adaptability to diverse environmental requirements and their potential to enable intelligent monitoring and interactive systems. Finally, future technological directions for flexible humidity sensors are proposed from the perspectives of material system innovation, improvement of multi-parameter collaborative sensing performance, and optimization of adaptability to complex environments. The proposed development directions are targeted at achieving higher precision, multifunctionality, and self-powered operation, providing insights and guidance for the research and development of next-generation flexible intelligent sensing devices. By bridging material science, manufacturing engineering, and application engineering, this comprehensive review provides a forward-looking perspective on advancing flexible humidity sensing technologies for emerging intelligent systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humidity, a critical parameter characterizing atmospheric water vapor content, plays a pivotal role in diverse fields including meteorology and environmental science1,2. As essential tools for humidity measurement, humidity sensors have sustainably propelled progress in health monitoring, agricultural production, and environmental quality control, among others3,4,5,6. Early-generation rigid humidity sensors predominantly employed polymers or ceramics as the humidity-sensitive materials, detecting moisture through measurable changes in electrical resistance or capacitance7,8,9,10. While simple to fabricate, these devices suffer from inherent limitations: bulky form factors, low sensitivity, poor anti-interference capabilities, and insufficient intelligence, which impede miniaturized integration, precise environmental sensing, and intelligent human-machine interaction (HMI), thereby constraining their applicability11,12. With rapid progress in semiconductor technology and microelectronics, flexible humidity sensors exhibiting lightweight, bendable, and stretchable characteristics have emerged as a research hotspot13,14. These novel sensors overcome the structural constraints of traditional rigid devices, enabling conformal contact with human skin surfaces or curved geometries of irregular objects. This unique advantage unleashes transformative potential in emerging fields such as healthcare, smart agriculture, smart homes, and HMI15,16,17,18.

This review provides a systematic overview of flexible humidity sensing technologies, structured as follows: First, we outline the evolutionary trajectory of flexible humidity sensor research, highlighting key milestones in material science and device engineering. We then discuss the transformative effects of emerging moisture-sensitive materials—including polymers, metal oxides, carbon-based materials, and two-dimensional (2D) materials—on critical device performance metrics such as sensitivity, response time, and stability. Fabrication technologies pivotal to flexible sensor fabrication, such as screen printing, spraying, and deposition, are systematically analyzed to elucidate their influences on device performance. Through interdisciplinary application cases, we examine the state-of-the-art and latest advancements in healthcare monitoring, smart agriculture, smart homes, and HMI applications (Fig. 1). For each domain, technical solutions enabling practical implementation are dissected, accompanied by discussions on application-specific challenges encountered by current devices. Finally, we highlight future prospects and research priorities, aiming to guide multi-faceted developments toward smart applications by addressing key bottlenecks in material innovation, multi-physical parameter integration, adaptability to complex environments.

Recent advances in flexible humidity sensors

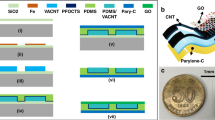

The rise of research on flexible humidity sensors is primarily attributed to two key factors. On the one hand, advances in material science have enabled the development of flexible substrate materials (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polyimide (PI), etc.) and humidity-sensitive materials with high specific surface areas (e.g., carbon nanotubes (CNTs), MXenes)13,18,19. Flexible substrates allow humidity sensors to conform closely to complex interfaces, while humidity-sensitive materials with high specific surface areas enhance the performance of flexible humidity sensors20,21. On the other hand, emerging applications (such as flexible electronic skins, wearable devices, and Internet of Things (IoT)) require sensors that adapt to irregular mechanical surfaces while maintaining high performance. Conventional rigid sensors often fail to meet these requirements, further accelerating the transition from rigid to flexible designs.

In the early 21st century, with the breakthrough development of flexible electronics technology, flexible humidity sensors gradually emerged as a research focus for scientists22,23. Distinguished from traditional rigid sensors, these devices utilize flexible substrates such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET), PI, and cellulose paper, combined with micro-nano processing technologies, to achieve bendable and foldable characteristics24,25. This feature significantly enhances their integration capability with flexible systems like wearable devices and electronic skin, laying the foundation for engineering applications of flexible devices26,27. The cross-integration of materials science and micro-nano manufacturing technologies in the 2010s drove performance innovations in flexible humidity sensors28. Researchers successively developed humidity-sensitive functional layers based on polymers, metal oxides, carbon-based materials, and 2D materials20,29,30,31. These materials, through physicochemical interactions between hydrophilic groups and water molecules, collectively promoted the development of flexible humidity sensors toward higher sensitivity and faster response speed. Since 2020, flexible humidity sensors have incorporated artificial intelligence algorithms such as machine learning to process and analyze collected data, enabling intelligent recognition of environmental humidity32,33,34. Concurrently, their application domains have expanded from initial industrial environment monitoring to emerging fields including healthcare, smart agriculture, intelligent living, and HMI, meeting diverse scenario requirements35,36,37. Additionally, these sensors are evolving toward multifunctional integration—for example, flexible sensor systems integrating humidity, temperature, and pressure sensors enable simultaneous monitoring of multiple environmental parameters to acquire richer sensing information38,39,40,41,42,43.

Notwithstanding significant laboratory advancements, flexible humidity sensors face substantial challenges on the path to mass production and broad application. Currently, high-performance nanoscale humidity-sensitive materials (e.g., graphene, CNTs) face challenges of high production costs and poor performance consistency during mass manufacturing44. Most flexible humidity sensors rely on solution-based processing methods, which hinder batch-to-batch repeatability and stability—critical for large-scale production and commercialization. Furthermore, device reliability and long-term stability remain unaddressed: in complex real-world environments, flexible humidity sensors must maintain long-term stable and reliable operation to ensure measurement accuracy and consistency.

Working mechanisms of flexible humidity sensors

The core working mechanism of flexible humidity sensors lies in the specific interaction between sensitive materials and water molecules, which converts environmental humidity changes into quantifiable physical signals45,46. Currently, the predominant types of flexible humidity sensors include resistive, capacitive, and impedimetric configurations. While sharing a fundamental operating principle, each type exhibits distinct characteristics19,47,48,49. Resistive sensors offer advantages in terms of simple fabrication processes, low cost, and exceptionally high sensitivity45. This makes them particularly suitable for applications requiring rapid response, such as breath analysis50. However, their resistance is susceptible to drift induced by temperature fluctuations, necessitating additional temperature compensation. Furthermore, long-term stability can be significantly compromised by the oxidation and degradation of the sensing material. Capacitive sensors are characterized by an approximately linear relationship between capacitance variation and humidity level, simplifying signal processing circuitry51. They also typically offer a wide humidity monitoring range. An additional benefit is their low static current, often on the order of microamperes, which is advantageous for battery life in portable devices52. A primary drawback of this type is their susceptibility to electromagnetic interference. Impedimetric sensors provide the core advantage of multi-parameter output capability46. They can simultaneously acquire resistance, capacitance, impedance magnitude, and phase angle information, yielding richer humidity response characteristics53. Nevertheless, this type demands sophisticated signal processing circuitry, increasing the complexity of system integration.

Beyond the common sensor types mentioned above, research has also reported other humidity sensors responsive at different frequency regimes, such as quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) and surface acoustic wave (SAW) sensors44,54. QCM sensors are mass-sensing devices based on the piezoelectric effect of quartz crystals. They are known for their high sensitivity and real-time monitoring capabilities, though they also exhibit limitations such as susceptibility to environmental factors and a limited detection range. The SAW-based humidity sensors usually show negligible degradation in humidity-sensing performance when bent on a curved surface with a relatively large bending angle, indicating their potential applicatiosn in sensing on curved and complex surfaces55. Furthermore, such devices were further used for human respiration detection in wearable electronics56.

Humidity-sensitive materials

The performance innovation and breakthroughs of flexible humidity sensors are primarily driven by the screening and structural regulation of humidity-sensitive materials57. These materials enable efficient conversion of humidity signals into quantifiable electrical signals (e.g., resistance, capacitance, impedance) through highly sensitive perception and precise response to environmental humidity changes, directly determining the sensor’s performance and value in practical applications58. In recent years, to enhance key performance indicators (e.g., sensitivity, stability, response/recovery time), researchers have developed a series of humidity-sensitive materials, primarily including polymers, metal oxides, carbon-based materials, and 2D materials. Each material category leverages unique moisture adsorption mechanisms and advantages, making them suitable for diverse detection environments and application requirements. Their distinct hydrophilic properties, nanoarchitectures, and surface chemistries collectively contribute to the continuous advancement of flexible humidity sensing technologies, as discussed in the subsequent sections.

Polymeric materials

Polymers, as one of the earliest adopted humidity-sensitive materials, have maintained a pivotal role in humidity sensor technology owing to their exceptional chemical stability and superior processability59. The working principle of polymer-based humidity sensors is rooted in the high responsiveness of polymeric materials to environmental humidity variations. When ambient humidity fluctuates, the physical properties of polymers (e.g., swelling degree, ionic conductivity) undergo measurable changes, which are converted into electrical signals (resistance, capacitance) for real-time humidity monitoring. This inherent moisture-responsive behavior, combined with the ease of molecular structure tailoring, has rendered polymeric materials indispensable for both fundamental research and commercial humidity sensing applications60.

Synthetic polymers

In the field of synthetic polymers, early studies by Shiu et al. reported a novel flexible impedance-type humidity sensor by coating amine-terminated polyamide-amine (PAMAM) dendrimer (G1-NH₂)-gold nanoparticle (G1-NH₂-AuNPs) composites onto a PET substrate61. Under testing conditions of 1 V bias, 1 kHz frequency, and 25 °C, this sensor exhibited a response time of 40 s and recovery time of 50 s within 30–90% RH, along with long-term stability exceeding 39 days (Fig. 2a). Zhang et al. developed a self-supported polymer film via thiol-ene click crosslinking, on which silver paste interdigitated electrodes were screen-printed62. By optimizing the ratio of hydrophilic monomers in the film, the sensor sensitivity was enhanced from 1.58 Ω/%RH to 103.75 Ω/%RH, with a response time of 12.5 s across 11–95% RH. This enabled real-time monitoring of humidity variations in speech airflow for word signal visualization (Fig. 2b). To further reduce response/recovery times, Yan et al. integrated daidzein-derived aromatic rings and α,β-unsaturated ketone structures into PI backbones63. The aromatic rings conferred mechanical properties similar to traditional polyimides, while unsaturated ketones enhanced flexibility and sensing capability. Selective reduction of unsaturated ketones regulated water vapor adsorption/diffusion, enabling ultrafast response/recovery (15 ms/95 ms)—10 to 2000 times faster than conventional designs (Fig. 2c). These cases demonstrate how molecular structure engineering of synthetic polymers enables precise tuning of humidity-sensing performance.

a A humidity sensor based on a PET substrate while using G1-NH2-AuNPs as the sensing material, and its characteristic curve of response/recovery time, measured at 1 V, 1 kHz, and 25 °C61. Copyright © 2012, Elsevier. b The preparation process of a flexible humidity sensor based on a self-supporting film, and the responses to words with different syllables during speaking and mouth-breathing at different breathing frequencies, insert is the enlarged curve related to fast breath62. Copyright © 2022, Elsevier. c Schematic illustration of the preparation process for daidzein-based PIs and the comparison of response and recovery times for the daidzein-based PI humidity sensors with previously reported sensor technologies63. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier

Cellulose and its derivatives

In cellulose and its derivatives, nanocellulose stands out due to the abundant hydroxyl groups in its molecular chains, which form direct hydrogen bonds with water molecules64,65. This strong interaction endows the material with extreme sensitivity to humidity changes, enabling rapid water molecule capture even in low-humidity environments and significantly enhancing sensor sensitivity—positioning it as a promising humidity-sensing material. In recent years, nanocellulose has attracted increasing scientific interest in flexible devices due to its natural abundance, easy manufacturability, environmental friendliness, and non-toxicity66,67.

Li et al. designed a polyvinyl alcohol/nanocellulose crystal/phytic acid (PCP) composite film based on the excellent dispersibility and degradability of nanocellulose crystals68, constructing a flexible multifunctional sensor (PCPW) with humidity-sensing capability. Phytic acid, rich in phosphate groups, enhances proton conduction, enabling the PCPW sensor to exhibit sensitive and repeatable resistance responses to humidity changes within 35–93% RH for human motion and respiration detection (Fig. 3a). Tokito et al. reported a high-performance printed flexible humidity sensor using cellulose nanofiber/carbon black (CNF/CB) composites21. Carbon black can be excellently dispersed with the help of CNF, which simplifies the processes of ink preparation and printing. Meanwhile, its hydrophilic and porous characteristics endow it with high sensitivity, and resistance changes reach 120% across the 30–90% RH range. The developed sensor also demonstrates exceptional flexibility, having been successfully used to monitor human respiration and non-contact fingertip humidity (Fig. 3b). Although these nanocellulose-based humidity sensors exhibit high sensitivity, their detection range requires expansion. To address this, Liu et al. prepared ultrathin lithium chloride (LiCl)/ CNF membranes via electrospinning as humidity-sensitive materials for high-performance sensors69. LiCl, a highly moisture-absorbing inorganic salt, boosts the humidity detection limit of cellulose particularly at low humidity levels, thereby attaining exceptional sensitivity (up to 4191% (ΔI/I₀)) and a broad detection range (5–98% RH). The nanoscale dimension of cellulose, combined with the ultrathin thickness and macroporous structure of the membrane, accelerates water molecule exchange, resulting in low hysteresis (2.9%). The sensor maintains performance after long-term use (>30 days), extreme temperatures (73.6 °C/0.1 °C), and thousands of bending cycles, showing significant potential in non-contact humidity detection, respiration monitoring, and sleep apnea detection (Fig. 3c).

a The preparation process of PCPW and its application in respiratory monitoring68. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier. b The flexible humidity sensor based on CNF/CB, the magnitude of resistance change of the sensor within the humidity range of 30-90% RH, and its use in monitoring non-contact fingertip humidity21. Copyright © 2022, American Chemical Society. c The humidity response characteristic curve of the flexible humidity sensor based on LiCl/CNF, as well as its application in non-contact humidity detection and respiratory monitoring69. Copyright © 2025, Elsevier

Metal oxides

Metal oxides have emerged as a research hotspot in humidity-sensitive materials due to the abundant dangling bonds (e.g., M-O⁻, M-OH groups, where M represents metal ions) on their surfaces, endowing them with strong polarity and hydrophilicity70. Early studies by Dubourg et al. fabricated a flexible humidity sensor on a PET substrate using laser ablation to pattern interdigitated electrodes71, followed by screen-printing titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles as the humidity-sensitive layer. The device exhibited a linear response in the 5–70% RH range, but response/recovery times reached 6.5 min/3 min at RH > 50%, prompting subsequent explorations of fast-response metal oxide materials (Fig. 4a). Lin et al. developed flexible humidity sensors based on tin oxide (SnO2) on borosilicate glass (SnO2–G) and flexible PET (SnO2–PET)72. Although as-prepared SnO2–G and SnO2–PET were insulating, hot-water treatment at 100 °C formed tin hydroxyl derivatives, providing mobile protons that modulated electrical properties with humidity. At 95% RH, SnO2–G-HWT and SnO2–PET-HWT showed 35.2× and 3.5× higher sensitivity than at 5% RH, respectively. At 20 ± 1 °C, both samples exhibited increasing sensitivity with RH, with response/recovery times of 51 s/38 s (SnO2–G-HWT) and 69 s/47 s (SnO2–PET-HWT) in 30–70% RH.

a The structure and images of a flexible humidity sensor using TiO2 as the humidity-sensitive material, as well as its response/recovery time under different RH conditions71. Copyright © 2017, The Author(s). b The structure and working principle of a flexible humidity sensor using MoOx particles as the humidity-sensitive material, along with its humidity response characteristic curve within the 29-75% RH range74. Copyright © 2023, American Chemical Society. c The preparation process and images of a flexible humidity sensor using Ga2O3 as the humidity-sensitive material, as well as its response/recovery time75. Copyright © 2023, The Author(s)

While metal oxide-based humidity sensors enable humidity detection over certain ranges, their response/recovery times remain suboptimal. Recent research has focused on tuning crystal structures and surface morphologies to enhance sensitivity and response speed73. Hu et al. developed flexible humidity sensors using molybdenum oxide nanoparticles (MoOx NPs)74, whose closely packed granular nanostructure and high packing density imparted insensitivity to mechanical deformation, low hysteresis, excellent repeatability, and stability. The sensor achieved ultrafast response/recovery (1.7 s/2.2 s) across 0–95% RH and enabled non-contact sensing by dynamically tracking skin-surrounding humidity changes (Fig. 4b). Further, Cui et al. demonstrated a flexible capacitive humidity sensor based on Ga2O3/liquid metal via laser direct writing75. Laser photothermal effects selectively sintered Ga2O3-encapsulated liquid metal particles from insulating to conductive traces (resistivity 0.19 Ω·cm), with untreated regions serving as humidity-responsive active layers. The sensor exhibited long-term stability, rapid response (∼1.2 s)/recovery (∼1.6 s) times, and was used to monitor respiration rates and hand skin humidity under different physiological states (Fig. 4c).

Carbon materials

Carbon materials have emerged as promising humidity-sensitive materials due to their large specific surface area and distinct chemical/physical adsorption behaviors under varying humidity conditions. The mesoscopic structure of carbon materials not only creates abundant surface active sites to accelerate water molecule adsorption/desorption but also enables sensitive response to environmental humidity fluctuations through significant changes in electrical conductivity, demonstrating exceptional humidity-sensing capabilities76.

Carbon quantum dots (CQDs)

In the field of carbon quantum dot materials, Kondee et al. synthesized nitrogen-doped carbon oxide quantum dots (NCQDs) via a hydrothermal method and prepared a flexible NCQDs humidity sensor using a simple drop-casting technique77. Testing results showed the sensor exhibited remarkable linearity within 20–90% RH, with an average humidity response of ~90.97% over ten cycles in 10–95% RH, demonstrating high responsiveness and repeatability (Fig. 5a). Huang et al. dispersed CQDs with abundant surface functional groups into poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (P(VDF–HFP)) to construct a flexible self-powered humidity sensor78. The introduction of CQDs improved hydrophilicity and β-phase formation, inducing vapor-induced phase separation (VIPS) during film formation to generate crosslinked pores and increase humidity-sensitive sites. Compared to the original device (PC0), modified devices PC1 (CQDs in water) and PC2 (CQDs in N,N-dimethylformamide) showed contact angles dropping from 126.3° to 65.1°/77.3°, reducing hysteresis and enhancing average sensitivity from 15.8 mV/%RH to 29.6 mV/%RH/24.4 mV/%RH (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, Zhao et al. developed wafer-scale CQDs@nanofiber clusters (CQDs@NFCs) as sensitive materials for flexible humidity sensors79. The composite’s superhydrophilicity and abundant nanopores of varying sizes enabled capillary condensation under different RH, significantly improving low-RH sensitivity via chemisorption and physisorption. Compared to devices using only nanofibers, the new sensor achieved 4.3× higher sensitivity in 7–59% RH. Its excellent sensing performance enabled precise monitoring of environmental humidity, finger proximity, plant transpiration, and diaper wetness (Fig. 5c).

a The preparation process and humidity response characteristic curve of the flexible NCQDs humidity sensor77. Copyright © 2022, Elsevier. b The structure and working principle of the flexible self-powered humidity sensor using CQDs as the humidity-sensitive material, the water contact angle test charts of the original device and the post-device modified with CQDs, as well as the sensitivity test charts of the device78. Copyright © 2024, Royal Society of Chemistry. c The working mechanism, application in fingertip humidity monitoring, and sensitivity test of the flexible humidity sensor using CQDs@NFCs as the humidity-sensitive material79. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier

CNTs

CNTs, characterized by their large specific surface area, excellent flexibility, and high electrical conductivity, represent ideal materials for humidity sensors and wearable electronics80. Early investigations by Han et al. reported a flexible humidity sensor constructed with CNTs on cellulose paper81, where humidity sensing was achieved through conductance changes in the CNT network. The sensor exhibited linear behavior below 75% RH, with a recovery time of 120 s within the detection range (Fig. 6a). This work paved the way for low-cost, disposable paper-based electronics, though sensitivity and response speed remained areas for improvement. To address these limitations, Ding et al. developed a composite by mixing CNTs with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)82. Leveraging the hydrophilicity of polymers and the network structure of CNTs, the sensor demonstrated a high response of 171% (ΔR/R₀) and rapid response/recovery times of 23 s/10 s. The adhesive and flexible nature of the composite ensured strong adhesion to PET substrates and excellent bending durability. This enabled applications in human respiration monitoring, finger movement detection, and handshake recognition (Fig. 6b). Further advancements by Li et al. introduced a flexible humidity sensor based on carbon nanocoils (CNCs)-CNT composites83, enabling wide-range detection (10–90% RH) with a maximum response of 492% (ΔR/R₀) at 90% RH, a peak sensitivity of 6.16%/%RH, and humidity resolution below 1% RH. The sensor exhibited robust mechanical durability, withstanding bending (curvature 0.322 cm⁻¹) and folding (500 cycles), and maintained stable performance when shaped into complex origami structures (Fig. 6c). Lu et al. further developed a sensor using multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) as the sensing material84, achieving ultrafast response (0.7 s) and full-range (0–100% RH) detection for monitoring dynamic human physiological signals (Fig. 6d).

a A humidity sensor constructed based on a cellulose paper substrate, its sensing mechanism, and the response and recovery curves when the humidity changes between 10-60% RH81. Copyright © 2012, American Chemical Society. b The schematic diagram of the sensing mechanism of the humidity sensor using CNT/PVP as the humidity-sensitive material, the response and recovery times of the sensor in the range of 10-96% RH, and the resistance changes of the CNT/PVP-based humidity sensor on the palm during handshakes82. Copyright © 2023, American Chemical Society. c The fabrication process of the flexible humidity sensor using CNCs/CNT as the humidity-sensitive material, as well as its application in non-contact humidity detection around the fingertip83. Copyright © 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry. d The working principle and applications of flexible humidity sensors, and the response times of the sensor when the airflow humidity is 90% RH and 0% RH, respectively84. Copyright © 2023, American Chemical Society

2D Materials

In recent years, 2D materials have garnered extensive attention for their diverse structures, unique physicochemical properties, relative cost-effectiveness, and exceptional electronic characteristics85,86,87. 2D materials with excellent properties, such as graphene, disulfides, and others, are widely used in the field of humidity sensors88,89. With single-atomic or few-atomic layer thickness, 2D materials expose nearly all atoms on the surface, yielding an extremely high surface-to-volume ratio90,91,92. This feature significantly enhances water molecule adsorption efficiency, as surface adsorption alone enables direct modulation of the material’s electronic structure (e.g., charge carrier concentration, energy band structure), thereby inducing pronounced changes in resistance, capacitance, or dielectric constant93. Furthermore, the van der Waals gaps between layers allow property tuning by controlling the number of layers. Meanwhile, 2D materials exhibit excellent adhesion to various flexible substrates (e.g., PDMS, PET, fabrics), adapting to deformation requirements and meeting the bending/stretching/folding tolerance of wearable devices94.

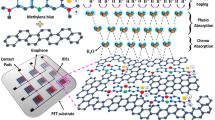

Graphene

Graphene has extensive applications in the field of humidity sensors95. Early studies by Cho et al. developed a GO humidity sensor96, where capacitance increased from 0.15 pF to 4.27 pF within 20–90% RH. At RH < 60%, water molecules adsorb on GO surfaces via double hydrogen bonds, while RH > 60% promotes water molecule penetration into GO films, enhancing hydrolysis of carboxyl, epoxy, and hydroxyl groups—thereby causing abrupt capacitance increases (Fig. 7a). This work established the theoretical foundation for humidity response mechanisms in 2D materials, inspiring subsequent developments of high-performance devices. Huang et al. fabricated a flexible humidity sensor using porous polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) as the substrate and GO as the sensing material97, exhibiting high sensitivity (164.98 pF/%RH at 45–90% RH) and fast response/recovery times (10 s/2 s) (Fig. 7b). Ping et al. further improved sensitivity to 3215.25 pF/%RH through chemical modification of GO surfaces98, with devices maintaining excellent stability (<±1% change after 30 days) for non-contact humidity sensing and human respiration monitoring (Fig. 7c). To optimize response/recovery times, Alazzam et al. employed 2D Ti3C2Tx/MXene nanosheets (TMNSs) as electrodes and GO as the sensing layer99, fabricating sensors on flexible transparent cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) substrates via UV lithography, spin-coating, and spraying. Impedance measurements showed significant humidity sensitivity across 6–97% RH at 1/10 kHz, with response/recovery times of 0.8 s/0.9 s. The 2D material-based sensor demonstrated non-contact proximity sensing and respiration detection, validating its application potential (Fig. 7d).

a The schematic diagram of four pixel points (2×2) of the multimodal electronic skin sensor, as well as the performance of the GO-based humidity sensor96. Copyright © 2016, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. b Structural schematic diagram of the flexible capacitive humidity sensor97. Copyright © 2021, The Author(s). c The preparation process of the GO-based flexible humidity sensor, the long-term stability test results of the sensor when exposed to 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% RH, and its application in respiratory monitoring98. Copyright © 2020, Elsevier. d The working principle and applications of the flexible humidity sensor, and the response times of the sensor when the airflow humidity is 90% RH and 0% RH, respectively99. Copyright © 2024, The Author(s)

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)

TMDs have emerged as promising humidity-sensitive materials for flexible sensors due to their unique layered structures and surface chemistry100,101. Adepu et al. developed a flexible humidity sensor by depositing rhenium disulfide (ReS2) on cellulose paper102, leveraging ReS2’s high surface energy to enable efficient water molecule adsorption and substrate adhesion. The sensor exhibited response/recovery times of ~142.94 s/35.45 s and a sensitivity of ~18.26 (ΔI/I₀) in the 43–95% RH range, successfully applied for skin condition assessment (dry/wet) and infant diaper wetness monitoring (Fig. 8a). Guo et al. fabricated a transparent, stretchable humidity sensor using WS₂ nanosheets as the sensing layer and PDMS as the flexible substrate103. This device demonstrated ultra-fast response/recovery kinetics (5 s/6 s), attributed to the large surface-to-volume ratio of WS₂ enabling rapid water molecule adsorption/desorption. The sensor conformed seamlessly to human skin for real-time respiration monitoring, maintaining stable humidity response under mechanical deformations (relaxation, compression, and stretching) (Fig. 8b). Building on these advancements, Lu et al. introduced a scalable WS₂-modified Ti3C2Tx MXene composite (CMXW2) as the sensing material104, achieving a flexible humidity sensor with outstanding performance. The CMXW2 sensor exhibited ultrafast response/recovery times of 4.65 s/1.33 s, a high sensitivity of 1707% (ΔC/C₀), and robust mechanical durability across a wide RH range (11–97% RH). The synergistic effect between hydrophilic WS₂ and conductive MXene enabled efficient moisture-induced capacitance changes while maintaining structural integrity during bending/stretching. Practical applications were demonstrated in skin moisture tracking, real-time respiration monitoring, and non-contact switching systems, showcasing its potential to enable next-generation smart healthcare and interactive sensing technologies (Fig. 8c).

a A flexible humidity sensor using ReS2 as the humidity-sensitive material, including the schematic diagram of its sensing mechanism, response/recovery time tests, and its application in real-time monitoring of the wetting process of baby diapers102. Copyright © 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. b A WS₂-based humidity sensor for monitoring human breath at different rates, and the time-dependent response curve between different RH levels for evaluating response and recovery times103. Copyright © 2017, Royal Society of Chemistry. c The manufacturing process of the CMXW2-based humidity sensor, its humidity response curve within the range of 11–97% RH, and the schematic of non-contact sensing circuit based on the sensor104. Copyright © 2025, Elsevier

Preparation Technologies of Flexible Humidity Sensors

Fabrication processes, as the core to integrate sensitive materials with flexible substrates, play a decisive role in enhancing the integration density and detection sensitivity of flexible sensors. Key technologies including screen printing, spraying, and deposition have formed the foundational framework for flexible humidity sensor fabrication, enabling effective adaptation between sensitive materials and flexible substrates through distinct mechanisms105,106,107. Specifically, screen printing leverages its unique pattern resolution and material compatibility to achieve patterned arrangement of sensitive materials on flexible substrates, providing a technological basis for arrayed sensor integration108. By controlling atomized particle size and spraying parameters, spraying technology constructs uniform and dense sensitive films on large-area flexible substrates, significantly improving detection consistency across devices106. Deposition technologies, utilizing physical or chemical vapor deposition principles, enable precise control of sensitive material composition, structure, and thickness at the atomic/molecular scale—facilitating the construction of nanoscale sensing interfaces and heterogeneous integration of multi-materials109,110. These technologies complement each other to form a multilayered fabrication process framework spanning from macroscopic patterning to microscopic structural tuning. This establishes a solid technological foundation for performance optimization and functional expansion of flexible sensors in complex application scenarios, bridging material properties with device-level functionalities through process innovation.

Screen printing technology

In the large-scale fabrication of flexible humidity sensors via screen printing, diverse research teams have demonstrated the technological versatility of this process in the field of flexible humidity sensors through material system innovation and functional integration design. Wang et al. integrated the KPMX composite material (alkali-treated MXene adsorbed with poly diallyldimethylammonium chloride) with flexographically printed paper-based interdigitated electrodes using screen printing111, developing a humidity sensor with fast response/recovery times (9.794 s/2.656 s) and excellent stability. Its non-contact respiration detection function and adaptability to environmental monitoring highlight the potential of screen printing for low-cost fabrication of flexible humidity sensors on eco-friendly substrates (Fig. 9a). Fan et al. further expanded the application boundaries of the process by fabricating a humidity/pressure dual-mode sensor based on MWCNTs/GO/ethyl cellulose (EC) through a full screen printing process112. Through the synergistic effect of carbon-based composite inks, the device achieved multi-parameter synchronous monitoring capabilities, including an ultra-low temperature coefficient of resistance (TCR = 0.182%°C⁻¹), a wide humidity detection range (22–92% RH), and a pressure sensitivity of -1.582% kPa⁻¹. This showcases the process compatibility of screen printing in multifunctional integrated sensors, providing a technological paradigm for multi-dimensional environmental perception in smart wearable devices (Fig. 9b). Furthermore, Wu et al. constructed functional inks with hexagonal tungsten oxide (h-WO₃) nanowires as the core and realized the preparation of fully printed flexible humidity sensors on PET substrates via screen printing108. The porous nanowire structure significantly enhances the adsorption/desorption efficiency of water molecules, enabling the device to exhibit an ultrafast response speed of 1.5 s, a high responsivity of 96.7% (ΔR/R₀), and >1000 cycles of stability within the 11–95% RH range. This sensor has been successfully applied to human respiration monitoring and the detection of drug packaging opening status, demonstrating its practical application value in complex scenarios (Fig. 9c).

a The preparation process of the humidity sensor, its response time at 11–97% RH, and the response of the sensor’s capacitance change to different breathing patterns111. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier. b The schematic diagram of the split structure of the dual-mode sensor, the humidity sensing mechanism of GO, and the dynamic response performance of the sensor112. Copyright © 2025, Elsevier. c The schematic diagram of the sensing mechanism of the flexible humidity sensor based on h-WO₃, its dynamic resistance response curve within the range of 11–95% RH, and the sensor’s response to different breathing patterns108. Copyright © 2023, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA

Spray technology

Spray technology demonstrates unique advantages for fabricating flexible humidity sensors, particularly in achieving high precision and complex structures, owing to its innovative principles and cross-scale structural control capabilities. He et al. leveraged the robust Michael addition reaction between polyethyleneimine (PEI) and tannic acid (TA) in aqueous solution113. Utilizing a simple spray-coating process, they fabricated a chemically cross-linked TA-x-PEI-based flexible humidity sensor. This device exhibited rapid response/recovery times (28 s/12 s) and maintained excellent stability over 30 days (<2% impedance variation) within a RH range of 35% to 90% (as shown in Fig. 10a). Further advancing the field, Zhang et al. employed spray-coating to develop unique ion-conductive metal-organic frameworks (IC-MOFs) utilizing metal ions as charge carriers114. They subsequently fabricated an IC-MOFs-based capacitive flexible humidity sensor. This sensor demonstrated short response/recovery times (2.5 s/1.5 s) across a broad detection range of 0-97% RH, revealing significant potential for multifunctional applications including ambient humidity detection, respiration monitoring, non-contact sensing, and syllable recognition (Fig. 10b). Lu et al. fabricated a nylon fabric/GO network via spray-coating106, designing a self-powered humidity sensor characterized by high air permeability and rapid response. Experimental results confirmed fast response/recovery times (0.78 s/0.93 s) at 35 °C, enabling applications such as non-contact monitoring of human respiratory rate pre- and post-exercise, as well as humidity level detection on palms, arms, and fingers. This work provides a valuable concept for developing flexible wearable humidity sensors that integrate breathability, self-powering capability, and potential for mass production akin to conventional wearable textiles (Fig. 10c).

a Images of PC-IDE-functionalized TA-x-PEI humidity sensors and measurements of their response and recovery times113. Copyright © 2023, Elsevier. b The device structure of the humidity sensor, its application in non-contact humidity sensing tests, and the capacitance-time response curves of the sensor to different voice stimuli114. Copyright © 2022, Elsevier. c Schematic diagram of the Cu/NF@GO/Zn-based humidity sensor and its application in monitoring respiration before and after human exercise106. Copyright © 2023, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA

Deposition technology

Deposition technology, through physical or chemical approaches, enables both the deposition of humidity-sensitive materials onto flexible substrates (e.g., PET, PDMS) to form functional layers with specific micro-morphologies and the in-situ synthesis and crystal structure tuning of sensing materials (e.g., carbon-based nanomaterials, chalcogenides). This achieves integrated regulation in both device fabrication and sensing material synthesis.

In Device Fabrication: Liang et al. combined laser-induced graphene (LIG) with electrochemical deposition (ECD) to directly fabricate copper-graphene composites on PI substrates115. The process first converts PI into porous graphene structures via laser scribing, followed by precise copper deposition by tuning electroplating parameters (current density 0.5–50 mA/cm², time 5–60 min), generating multi-scale structures ranging from Cu2O nanoflowers to dense copper layers. The resulting flexible humidity sensor exhibits a response time of 26 s and recovery time of 54 s in the 25–90% RH range (Fig. 11a). Afsana et al. prepared a flexible humidity sensor by printing silver interdigitated electrodes on PET substrates via inkjet printing and depositing GO as the sensing material using aerosol deposition109. The sensor demonstrates excellent performance across a wide RH range (11–97% RH), with a response time of only 2 s and recovery time of 17 s. Notably, it enables monitoring of human respiration, differentiation between oral/nasal breathing, non-contact finger motion detection, and even recognition of basic spoken words (Fig. 11b).

a The Schematic of the wireless humidity sensor115. Copyright © 2025, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. b Physical image of the flexible humidity sensor based on GO humidity-sensitive material, and monitoring of oral exhaled humidity during four consecutive exhalations/inhalations109. Copyright © 2024, The Electrochemical Society. c Humidity-sensitive materials synthesized via the iCVD process for preparing flexible humidity sensors, and the application of such sensors embedded in oxygen masks for human respiratory monitoring116. Copyright © 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry. d 2D MoS₂ humidity-sensitive materials synthesized via the IPSD process for preparing flexible humidity sensors, as well as the schematic diagram of the sensor and its application in respiratory monitoring110. Copyright © 2025, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA

In Sensing Material Synthesis: Pan et al. synthesized unique ultrathin hydrogel-carbon nanocomposites with hierarchical micro-nano structures via solvent-free chemical vapor deposition (iCVD)116, using PDMS as the substrate to fabricate flexible humidity sensors. The composite’s micrometer-scale periodic wavy structures and nanometer-scale porous surface significantly increase specific surface area, enabling fast response/recovery (13 s/0.48 s) across a broad humidity range (11–96% RH). Its successful application in real-time human respiration and skin humidity monitoring highlights practical potential as a wearable multifunctional sensor (Fig. 11c). Youn et al. employed isolated plasma soft deposition (IPSD) combined with sulfidation for scalable production of 2D MoS₂ with precise layer control110, achieving large-area, high-quality 2D MoS₂ layers. Comprehensive characterization via Raman, UV-Vis, photoluminescence spectroscopy, and transmission electron microscopy confirmed the synthesis of crystalline monolayer-to-quadrilayer 2D MoS₂ on 6-inch SiO₂/Si substrates. Flexible humidity sensors using IPSD-grown 2D MoS₂ exhibit ultrafast response (~1 s) in the 30–60% RH range (Fig. 11d).

Applications of flexible humidity sensors

Flexible humidity sensors, as a new class of sensing elements combining mechanical deformability and humidity responsiveness, have been deeply integrated into diverse application scenarios117,118. In healthcare, sensors constructed with flexible substrates and biocompatible sensing materials can conform to skin surfaces or adopt implantable configurations, enabling precise real-time monitoring of physiological parameters such as respiratory moisture and human sweat119,120,121. This provides dynamic data support for disease diagnosis and personalized health management. In agriculture, the stretchability and large-area integration capabilities of flexible devices allow adaptation to complex terrains and surfaces (e.g., soil particle interfaces, plant leaf surfaces), achieving high-spatial-resolution sensing of soil moisture distribution and plant physiological monitoring—critical for intelligent crop irrigation and healthy growth122. In smart home scenarios, flexible humidity sensors leverage their wearability and high sensitivity to facilitate sleep quality monitoring and infant care123,124. Meanwhile, in human-computer interaction, they enable real-time parsing and translation of interaction commands by accurately capturing dynamic humidity changes induced by skin evaporation or gestural movements125,126. These diverse applications not only demonstrate the operational stability of flexible humidity sensors in various environments but also highlight their technological potential for high-precision, low-power, and integrated development through synergistic innovation in materials, processes, and structures. This provides scientifically sound and engineering-practical solutions for multi-domain humidity monitoring.

Applications in healthcare

In the field of healthcare monitoring, flexible humidity sensors have emerged as critical platforms for real-time noninvasive detection of human physiological signals, leveraging their advantages of light weight, high flexibility, and biocompatibility127,128. These devices map respiratory system functions and metabolic information by capturing humidity changes in body fluids such as breath and sweat, offering novel solutions for disease diagnosis and health management129,130,131.

Guan et al. fabricated a humidity sensor based on glycidyl trimethyl ammonium chloride (EPTAC)-modified cellulose paper via a simple solution method132. EPTAC modification not only enhanced sensor sensitivity but also reduced the response time to 25 s. The paper-based device, featuring excellent flexibility and biocompatibility, enables real-time human respiration monitoring (Fig. 12a). Liu et al. developed a flexible, highly sensitive humidity sensor array by anchoring multilayer graphene (MG) within electrospun polyamide (PA66)133. The synergistic effect of PA66 nanofiber networks’ large specific surface area and abundant hydrophilic functional groups endows the sensor with superior humidity sensitivity. Capable of real-time respiratory frequency monitoring, it is applied in asthma detection and remote alarm systems. Notably, the system provides contactless drug delivery interfaces for bedridden patients through non-contact human-computer interaction, minimizing cross-infection risks (Fig. 12b). Beyond respiration monitoring, flexible humidity sensors enable disease diagnosis via human sweat analysis. Liu et al. created a superhydrophobic sweat sensor using sodium polyacrylate/MXene composites sandwiched between two superhydrophobic textile layers134. This design allows highly sensitive and rapid (response/recovery: 2.2 s/1.05 s) continuous measurement of sweat vapor from insensible perspiration. Integrating the sensor with flexible wireless communication and power modules forms a standalone system for continuous monitoring of body temperature and skin barrier function, applicable for thermal comfort assessment, disease status monitoring, and neurological activity analysis—showcasing potential as next-generation sweat sensors in smart and personalized healthcare (Fig. 12c).

a The preparation process of the paper-based humidity sensor, as well as the response and recovery curves of blank paper and PE-1 to PE-4 sensors at 11-95% RH132. Copyright © 2021, Elsevier. b The practical application of MPHS in asthma detection, the working principle of the asthma detection system, the demonstration of triggering asthma alarms on mobile phones via wireless transmission, and the schematic diagram of the multifunctional applications of MPHS133. Copyright © 2021, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. c The insensible sweat sensor, its application in evaluating skin barrier function, human thermal comfort, and emotional/gustatory stimuli, as well as the response and recovery time of the humidity sensor during switching between 7% and 70% RH134. Copyright © 2023, American Chemical Society

Applications in smart agriculture

In recent years, breakthroughs in humidity sensors for human health monitoring have inspired new approaches to crop physiological state detection135. However, mainstream crop sensors still rely on rigid structures, which can damage plant organs and face challenges in precision and material biocompatibility136. In contrast, flexible humidity sensors, by adopting bendable substrates (e.g., PDMS, PI, etc.), can better conform to plant surfaces (such as leaves and stems) during the monitoring of crop physiological status, thus avoiding mechanical damage to plant tissues52. Notably, flexible humidity sensors are typically designed to be ultrathin and lightweight, which ensures that they do not impose an additional burden on plants when attached to them. Developing novel flexible humidity sensors for real-time crop growth monitoring thus holds significant scientific and practical importance137.

Flexible humidity sensors are constructing a full-dimensional monitoring system from soil to plant physiology through cross-technique integration and multi-scenario adaptation. For soil moisture sensing, Khasim et al. designed a PVA/PEDOT-PSS:TiO2 nanocomposite sensor that provides direct data support for intelligent irrigation systems by accurately quantifying soil RH138. Xiao et al. developed a self-powered humidity sensor (SPHS) based on moisture-induced electricity generation139, which relies on ion diffusion and electrochemical reactions to sense soil moisture through spontaneous water molecule adsorption/desorption in humid environments. The device generates current responses autonomously (33–91% RH) without external power, demonstrating excellent reliability and durability (Fig. 13a).

a Schematic diagram of the agricultural intelligent environmental monitoring system based on SPHS, and schematic diagram of the power generation and humidity sensing mechanisms of SPHS139. Copyright © 2024, Elsevier. b The preparation flowchart of the humidity sensor, the principle of the sensor applied to plant physiological monitoring, and the impedance response and recovery characteristic curves of the sensor140. Copyright © 2021, The Author(s). c The device structure schematic diagram of the multifunctional flexible sensor with humidity detection, the schematic diagram of the sensor attached to the lower epidermis of leaves for monitoring plant transpiration process, and the front view photo of the multifunctional flexible sensor141. Copyright © 2020, American Chemical Society

At the plant physiology level, Furqan et al. fabricated a gallium nitride thin-film humidity sensor via pulsed DC magnetron sputtering140, exhibiting nearly linear impedance response across 0–100% RH with response/recovery times of 3.5 s/9 s. By directly attaching to plant leaves without causing damage, the sensor effectively evaluates transpiration cycles, providing insights into plant water status (Fig. 13b). Further advancing this field, Lu et al. developed a multi-modal flexible sensor system based on ZnIn2S4 nanosheets for plant growth management141. The system enables rapid light sensing (response time ~4 ms) and stable humidity monitoring, with its humidity response mechanism validated by first-principles calculations. Innovatively, it achieves real-time stomatal function monitoring and records plant dehydration states over 15 days of continuous measurement. This work establishes a new technical pathway for precision plant health management and resource optimization, while opening up new frontiers in plant-sensor biointerface research (Fig. 13c).

Applications in smart home

In smart home scenarios, flexible humidity sensors are progressively constructing intelligent and personalized home management systems through dual functions of environmental humidity sensing and human activity monitoring142,143. Leveraging their lightweight flexibility, multi-modal perception, and long-term wearing comfort, these devices break through the limitations of traditional environmental monitoring equipment, demonstrating significant application potential in sleep quality optimization, personalized exercise program formulation, and infant care144,145.

Water molecules are the main component of exhaled air, and many studies have focused on using humidity sensors for real-time noninvasive sleep monitoring of respiratory status146. However, traditional contact humidity sensors struggle to meet the comfort requirements for human sleep monitoring, prone to causing skin discomfort or even inflammation and itching. Wang et al. integrated Ti3C2Tx nanosheets with thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) nanofiber membranes via electrospinning147, followed by magnetron sputtering of copper interdigitated electrodes, fabricating a fully nanofibrous wearable humidity sensor. With ultrafast response/recovery (<3.7 s) and a wide humidity range (11–95% RH), the sensor features portability, flexibility, breathability, and biocompatibility, being insensitive to pressure, temperature, and sweat. It monitors nighttime sweating and respiratory status during sleep to guide scientific sleep management (Fig. 14a). For personalized exercise program formulation, Liu et al. coated MXene nanosheets onto chitosan-modified TPU electrospun nanofibers via electrostatic interaction, preparing MXene/TPU composite films for humidity sensors123, preparing MXene/TPU composite films for humidity sensors. Based on the principle that water molecules alter MXene nanosheet spacing to modulate tunneling resistance, the sensor exhibits a response time of 12 s, wide humidity range (11–94% RH), and excellent repeatability. It discriminates different human breathing patterns and accurately monitors respiratory signals during various exercises, guiding the establishment of personalized home exercise regimens (Fig. 14b). For infant care, Yang et al. proposed a hand-drawn interdigitated electrode design124, fabricated by pencil drawing on paper followed by NaCl solution treatment, yielding a highly sensitive flexible humidity sensor operating in 5.6–90% RH. Integrated with infant diapers, the sensor forms a smart diaper system to alert timely diaper changes, reducing the incidence of infant diaper rash (Fig. 14c).

a A flexible humidity sensor based on Ti3C2Tx/TPU for sleep monitoring, the resistance change curves of respiratory monitoring during sleep, and the response/recovery time test of the sensor147. Copyright © 2023, American Chemical Society. b The schematic diagram of the sensing mechanism of the flexible humidity sensor based on MXene/TPU, the respiratory response curves of the sensor for monitoring during continuous changes in motion states, as well as the response and recovery times of the sensor at 33%, 58%, and 84% RH123. Copyright © 2024, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. c The response mechanism of the flexible paper-based humidity sensor and its application scenarios in smart diapers124. Copyright © 2023, American Chemical Society

Applications in HMI

With the rapid development of artificial intelligence, HMI technology has become a research hotspot148,149,150. Flexible humidity sensors, leveraging their precision in perceiving human microenvironmental humidity fields, have emerged as core components for constructing non-contact, low-power interaction interfaces151,152,153. These devices enable real-time interpretation of HCI commands by capturing humidity gradient changes induced by skin evaporation or gestural movements, demonstrating unique advantages in intelligent device control11,154.

Li et al. developed a skin-conformal breathable humidity sensor based on MXene composites and electrospun elastomeric nanofibers with patterned electrodes155. Exhibiting excellent breathability (0.078 g·cm⁻²·d⁻¹), high sensitivity, and ultrafast response/recovery (0.9 s/0.9 s), the sensor ensures outstanding skin adaptability and biocompatibility. A 3 × 3 humidity sensing array was implemented to develop a non-contact HCI interface, enabling motion control of robotic carts via finger sliding—highlighting applications in contactless control (Fig. 15a). Zhang et al. further developed a flexible fast-response humidity field sensing array using ionogel films for precise humidity distribution detection53. Optimizing the hydrophobic ionogel structure achieves ultrafast response/recovery (0.65 s/0.85 s), wide detection range (11–98% RH), and long-term stability (120 days). Integrated with machine learning algorithms, this non-contact HCI system enables remote control of drug delivery vehicles (Fig. 15b).

a The schematic diagram and application scenarios of the SAMP-based humidity sensor, as well as the demonstration of the sensor controlling a robotic vehicle to transport medical boxes via HMI155. Copyright © 2023, The Author(s). b The schematic diagram of characteristics, structure, and multifunctional applications of the IHSA-based flexible humidity sensor, as well as the demonstration of the sensor controlling intelligent vehicles through non-contact HMI53. Copyright © 2025, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. c The schematic diagram and physical image of the humidity sensor, as well as its working mechanism126 Copyright © 2022, The Author(s). d A gesture used to control a robot without contact159. Copyright © 2023, Elsevier

However, most non-contact applications rely on continuous power supplies, limiting long-term IoT deployment, self-powered flexible sensors thus becoming research priorities125,156,157,158. Zhang et al. fabricated a self-powered chemo-electrochemical humidity (CEH) sensor using silk fibroin and GO126, leveraging metal-air redox reactions. The CEH sensor, composed of GO/silk fibroin/LiBr gel electrolyte between graphite paper and aluminum foil electrodes, exhibits fast response/recovery (1.05 s/0.8 s) across 11–84% RH (Fig. 15c). Gong et al. proposed a dual-function system (SCHS) combining a triboelectric nanogenerator-powered supercapacitor and ultrasensitive humidity sensor based on NiCo2O4/g-C3N4 nanocomposites159. Featuring high sensitivity (1471 kΩ/%RH at 11%RH) and specific capacitance (1061F/g at 0.5 A/g), the system detects humidity field changes from hand proximity to enable non-contact robotic gesture control (Fig. 15d).

Conclusion and Outlook

Flexible humidity sensors serve as a critical bridge, translating environmental moisture information into actionable data for intelligent systems. Their evolution fundamentally represents an innovative convergence of materials science, micro/nano-fabrication, and cross-disciplinary application. Innovations in humidity-sensitive materials have progressed from early polymer-based systems like polyvinyl alcohol to a current landscape of diverse materials. Metal oxides (e.g., ZnO, TiO2), leveraging nanostructures and ion-electron conduction mechanisms, have enabled significant improvements in sensor response speed. Carbon-based materials (e.g., CNTs, CQDs) address the synergistic challenge of achieving high conductivity alongside abundant moisture adsorption sites through conductive 3D networks and porous architectures, enhancing both sensitivity and compatibility with flexible substrates. 2D materials, particularly GO and MXene, offer exceptional moisture uptake and rapid response kinetics due to their atomic thickness and high density of surface functional groups. Current material development exhibits a distinct trend towards hybridization, employing strategies such as polymer-2D material composites, metal oxide-carbon hybrids, and bioinspired designs. These approaches integrate the advantages of multiple material classes, overcoming the inherent limitations of single-component systems, thereby providing crucial support for the robust application of flexible humidity sensors in complex environments.

Fabrication processes are pivotal for the industrialization of flexible humidity sensors. The three prominent technologies discussed herein possess distinct merits: Screen printing offers low cost, high compatibility, and large-area patterning capabilities, making it suitable for roll-to-roll continuous manufacturing and overcoming scalability bottlenecks. Spray coating facilitates large-area, uniform thin-film deposition, enhancing adsorption efficiency within the sensitive layer, enabling conformal coverage on curved surfaces, and supporting the fabrication of biocompatible devices. Deposition technologies allow for precise control over critical parameters (temperature, pressure, precursor concentration), enabling targeted modulation of the electronic structure (e.g., bandgap), geometric morphology (e.g., porosity), and interfacial properties (e.g., surface energy) of sensitive materials. This precision underpins the advancement of flexible humidity sensors towards higher stability and multifunctional integration.

As a key sensing element capable of accurately converting ambient or biological humidity variations into quantifiable electrical signals, flexible humidity sensors are finding increasingly widespread application in healthcare, precision agriculture, smart homes, and HMI. Their unique attributes—lightweight, bendable, stretchable, and wearable—are central to this adoption. Continuous breakthroughs in materials science (e.g., higher-performance sensing materials, biodegradable/self-healing polymers) and micro/nano-fabrication technologies promise further enhancements in sensitivity, stability, response speed, and environmental tolerance. These advancements will profoundly accelerate the transition towards a more intelligent and interconnected future, ultimately benefiting human life across broader domains.

Despite significant progress, challenges remain in performance optimization, system integration, and industrial scalability. Future research should focus on the following key directions: (1). Long-term stability still requires further improvement. Most of the currently proposed flexible humidity sensors struggle to maintain reliable operation under high humidity conditions (>90% RH), primarily due to inefficient desorption of water molecules within the devices. Furthermore, the organic and polymeric materials employed in the fabrication process tend to degrade over time, and their performance is highly sensitive to environmental variations. These factors collectively limit the long-term stability of flexible humidity sensors. (2). Deep Integration of Self-Powering and Low-Power Systems: The reliance on external power sources for existing systems, especially in non-contact applications, impedes the deployment of large-scale sensor networks. While triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) offer self-powering potential, their energy conversion efficiency and output stability require substantial improvement. (3). Fusion of Multi-modal Sensing and Intelligent Decision-Making: Monitoring solely humidity parameters is increasingly inadequate for complex scenarios. Developing integrated multi-modal sensing systems coupled with embedded intelligence for real-time analysis and decision-making is essential. (4). Standardization of Manufacturing and Industrial Adaptation: Printing technologies (e.g., screen printing) enable large-area fabrication, yet ensuring consistent performance and reliability across different production batches necessitates rigorous standardization of testing protocols and quality control measures. (5). More advanced manufacturing technologies are required to further optimize the dimensions, thereby enabling their application in scenarios with stringent spatial constraints. For instance, in miniaturized medical monitoring devices that are implanted in human bodies, large dimensions will fail to meet spatial requirements. Moreover, current sensing systems are trending toward multi-functionality and high integration, where an overly large size will augment the difficulty and complexity of integration.

The development of flexible humidity sensors is rapidly evolving. The trajectory—from discrete devices to integrated flexible systems, and from single-parameter monitoring to multi-modal intelligent analysis—consistently aligns with the demand for “higher precision, greater flexibility, and enhanced intelligence.” Looking forward, the deep integration of machine learning algorithms with flexible electronics manufacturing holds immense potential. This synergy could enable flexible humidity sensors to transcend the traditional limitations of physical form and application scenarios, positioning them as core sensing units in the construction of an “intelligent sensing” world. Such progress will catalyze further innovative applications in healthcare, precision agriculture, industrial IoT, and beyond. Realizing this vision will require sustained investment in fundamental research and, crucially, collaborative innovation and persistent effort across multidisciplinary teams.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

Dessler, A. E. & Sherwood, S. C. A matter of humidity. Science 323, 1020–1021 (2009).

Dinh, T.-V. et al. Development of a humidity pretreatment method for the measurement of ozone in ambient air. J Hazard Mater 426, 128108 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. Electrochemical humidity sensor enabled self-powered wireless humidity detection system. Nano Energy 115, 108745 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. A plant-friendly wearable sensor for reducing interfacial abiotic stress effects and growth monitoring. J Mater Chem A 12, 30012–30021 (2024).

Han, K. & Li, Y. Flexible parallel-type capacitive humidity sensors based on the composite of polyimide aerogel and graphene oxide with capability of detecting water content both in air and liquid. Sens Actuators B: Chem 401, 135050 (2024).

Han, M., Ding, X., Duan, H., Luo, S. & Chen, G. Ultrasensitive humidity sensors with synergy between superhydrophilic porous carbon electrodes and phosphorus-doped dielectric Electrolyte. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 15, 9740–9750 (2023).

Wang, J., Lin, Q., Zhou, R. & Xu, B. Humidity sensors based on composite material of nano-BaTiO3 and polymer RMX. Sens Actuators B: Chem 81, 248–253 (2002).

Ling, Z., Chen, S., Wang, J. & Li, Y. Fabrication and properties of anodic alumina humidity sensor with through-hole structure. Chin Sci Bull 53, 183–187 (2008).

Kim, D.-U. & Gong, M.-S. Thick films of copper-titanate resistive humidity sensor. Sens Actuators B: Chem 110, 321–326 (2005).

Harrey, P. M., Ramsey, B. J., Evans, P. S. A. & Harrison, D. J. Capacitive-type humidity sensors fabricated using the offset lithographic printing process. Sens Actuators B: Chem 87, 226–232 (2002).

Li, Z. et al. Highly sensitive and stable humidity nanosensors based on LiCl doped TiO2 electrospun nanofibers. J Am Chem Soc 130, 5036–5037 (2008).

Chen, L. & Zhang, J. Capacitive humidity sensors based on the dielectrophoretically manipulated ZnO nanorods. Sens Actuators A: Phys 178, 88–93 (2012).

Zhang, H. et al. Interlayer cross-linked MXene enables ultra-stable printed paper-based flexible sensor for real-time humidity monitoring. Chem Eng J 495, 153343 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Wearable sensors for breath monitoring based on water-based hexagonal boron nitride inks made with supramolecular functionalization. Adv Mater 36, 2312621 (2024).

Guo, Y., Gong, Q., Liu, D. & Nie, G. Flexible humidity sensor with high responsiveness based on interlayer synergistic modification of MXene for physiological detection and soil monitoring. Chem Eng J 507, 160572 (2025).

Wu, P., Li, L., Shao, S., Liu, J. & Wang, J. Bioinspired PEDOT:PSS-PVDF(HFP) flexible sensor for machine-learning-assisted multimodal recognition. Chem Eng J 495, 153558 (2024).

Khan, S. A. et al. Wireless flexi-sensor using narrow band quasi colloidal 3D tin telluride (SnTe) for respiratory, environment, and proximity sensing. Chem Eng J 495, 153376 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. Transparent, flexible nanoporous sensors with humidity and pressure sensing capabilities for sports health status monitoring. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 7, 21209–21220 (2024).

He, A. et al. A high-sensitive capacitive humidity sensor based on chitosan-sodium chloride composite material. Colloids Surf A 699, 134740 (2024).

Afzal, U. et al. Chemical engineering for advanced flexible sensors: novel carbon-metal oxide nanocomposites with superior multi-sensing behavior. Sens Actuators B: Chem 431, 137449 (2025).

Tachibana, S. et al. A printed flexible humidity sensor with high sensitivity and fast response using a cellulose nanofiber/carbon black composite. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 14, 5721–5728 (2022).

Zampetti, E. et al. Design and optimization of an ultra thin flexible capacitive humidity sensor. Sens Actuators B: Chem. 143, 302–307 (2009).

Oprea, A. et al. Capacitive humidity sensors on flexible RFID labels. Sens Actuators B: Chem 132, 404–410 (2008).

Su, P.-G. & Wang, C.-S. Novel flexible resistive-type humidity sensor. Sens Actuators B: Chem 123, 1071–1076 (2007).

Yang, T. et al. Fabrication of silver interdigitated electrodes on polyimide films via surface modification and ion-exchange technique and its flexible humidity sensor application. Sens Actuators B: Chem 208, 327–333 (2015).

Liu, H. et al. Paper-based wearable sensors for humidity and VOC detection. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 9, 16937–16945 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Flexible and transparent electronic skin sensor with sensing capabilities for pressure, temperature, and humidity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 15, 24923–24932 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Porous ionic membrane based flexible humidity sensor and its multifunctional applications. Adv Sci 4, 1600404 (2017).

Rajendran, S. & Bhunia, S. K. Carbon dots decorated graphitic carbon nitride as a practical and flexible metal-free nanosensor for breath humidity monitoring. Carbon Lett 34, 783–795 (2024).

Zeng, S. et al. Ultrafast response of self-powered humidity sensor of flexible graphene oxide film. Mater Des 226, 111683 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. An ultrafast-response and flexible humidity sensor for human respiration monitoring and noncontact safety warning. Microsyst Nanoeng 7, 99 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Flexible non-contact printed humidity sensor: realization of the ultra-high performance humidity monitoring based on the MXene composite material. Sens Actuators B: Chem 432, 137481 (2025).

Yang, H. et al. An intelligent humidity sensing system for human behavior recognition. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 17 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Flexible smart noncontact control systems with ultrasensitive humidity sensors. Small 15, 1902801 (2019).

Gong, L., Wang, X., Zhang, D., Ma, X. & Yu, S. Flexible wearable humidity sensor based on cerium oxide/graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite self-powered by motion-driven alternator and its application for human physiological detection. J Mater Chem A 9, 5619–5629 (2021).

Yi, Y. et al. A free-standing humidity sensor with high sensing reliability for environmental and wearable detection. Nano Energy 103, 107780 (2022).

Huang, C. et al. Wide-detection-range, highly-sensitive, environmental-friendly and flexible cellulose-based capacitive humidity sensor. Carbohydr Polym 358, 123507 (2025).

Fu, Y. et al. A highly sensitive, conductive, and flexible hydrogel sponge as a discriminable multimodal sensor for deep-learning-assisted gesture language recognition. Adv Funct Mater 35, 2416453 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Flexible, visual, and multifunctional humidity-strain sensors based on ultra-stable perovskite luminescent filaments. Adv Fiber Mater 7, 762–773 (2025).

Wei, C. et al. Transient flexible multimodal sensors based on degradable fibrous nanocomposite mats for monitoring strain, temperature, and humidity. ACS Appl Polym Mater 6, 4014–4024 (2024).

Liang, A., Dong, W., Li, X. & Chen, X. A novel dual-mode paper fiber sensor based on laser-induced graphene and porous salt-ion for monitoring humidity and pressure of human. Chem Eng J 502, 158184 (2024).

Ye, L. et al. A flexible self-powered multimodal sensor with low-coupling temperature, pressure and humidity detecting for physiological monitoring and human-robot collaboration. Chem Eng J 519, 164866 (2025).

Liang, X. et al. Temperature, pressure, and humidity SAW sensor based on coplanar integrated LGS. Microsyst Nanoeng 9, 110 (2023).

Le, X. et al. Surface acoustic wave humidity sensors based on uniform and thickness controllable graphene oxide thin films formed by surface tension. Microsyst Nanoeng 5, 36 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Outstanding humidity chemiresistors based on imine-linked covalent organic framework films for human respiration monitoring. Nano-Micro Lett 15, 149 (2023).

Liang, Y. et al. Humidity sensing of stretchable and transparent hydrogel films for wireless respiration monitoring. Nano-Micro Lett 14, 183 (2022).

Feng, S., Guo, S., Zhang, S. & Zhang, X. Aligned porous cellulose-based humidity sensor for fast-response wearable and non-contact interactive sensing. Chem Eng J 520, 166391 (2025).

Kim, S. J., Park, H. J., Yoon, E. S. & Choi, B. G. Preparation of reduced graphene oxide sheets with large surface area and porous structure for high-sensitivity humidity sensor. Chemosensors 11, 276 (2023).

Zhang, M., Duan, Z., Yuan, Z., Jiang, Y. & Tai, H. Observing mixed chemical reactions at the positive electrode in the high-performance self-powered electrochemical humidity sensor. ACS Nano 18, 34158–34170 (2024).

Hu, X. et al. A flexible polyethyleneimine film sensor for high humidity monitoring.J Mater Chem A 13, 26268–26278 (2025).

Niu, H. et al. Ultrafast-response/recovery capacitive humidity sensor based on arc-shaped hollow structure with nanocone arrays for human physiological signals monitoring. Sens Actuators B: Chem 334, 129637 (2021).

Peng, B., Liu, X., Yao, Y., Ping, J. & Ying, Y. A wearable and capacitive sensor for leaf moisture status monitoring. Biosens Bioelectron 245, 115804 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. Scalable fabrication of uniform fast-response humidity field sensing array for respiration recognition and contactless human-machine interaction. Adv. Funct. Mater 35, 202502583 (2025).

Gao, X. et al. Wireless and passive SAW-based humidity sensor employing SiO2 thin film. IEEE Sens J 23, 9936–9942 (2023).

He, X. L. et al. High sensitivity humidity sensors using flexible surface acoustic wave devices made on nanocrystalline ZnO/polyimide substrates. J Mater Chem C 1, 6210 (2013).

Wu, J. et al. Ultrathin glass-based flexible, transparent, and ultrasensitive surface acoustic wave humidity sensor with ZnO nanowires and graphene quantum dots. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 12, 39817–39825 (2020).

Zhao, Z.-H. et al. Flexible and multifunctional humidity sensor based on Au@ZIF-67 nanoparticles for non-contact healthcare monitoring. Rare Met 44, 2564–2576 (2025).

Buga, C. & Viana, J. Flexible CNF/CB-based humidity sensors with optimized sensitivity and performance. J Mater Chem C 13, 6508–6526 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Polymer-based humidity sensor with fast response and multiple functions. Mater Sci Semicond Process 190, 109329 (2025).

Zheng, Z. et al. Flexible, sensitive and rapid humidity-responsive sensor based on rubber/aldehyde-modified sodium carboxymethyl starch for human respiratory detection. Carbohydr Polym 306, 120625 (2023).

Su, P.-G. & Shiu, C.-C. Electrical and sensing properties of a flexible humidity sensor made of polyamidoamine dendrimer-Au nanoparticles. Sens Actuators B: Chem 165, 151–156 (2012).

Guan, X. et al. A flexible humidity sensor based on self-supported polymer film. Sens Actuators B: Chem 358, 131438 (2022).

Gong, C. et al. Structurally programmed bioderived polyimide for foldable humidity sensors with ultrafast response and recovery times. Chem Eng J 500, 157172 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. Highly conductive and mechanically robust cellulose nanocomposite hydrogels with antifreezing and antidehydration performances for flexible humidity sensors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 14, 10886–10897 (2022).

Jin, G. et al. A CNFs/MWCNTs aerogel film-based humidity sensor with directionally aligned porous structure for substantially enhancing both sensitivity and response speed. Chem Eng J 473, 145304 (2023).

Gong, L. et al. Construction and performance of a nanocellulose–graphene-based humidity sensor with a fast response and excellent stability. ACS Appl Polym Mater 4, 3656–3666 (2022).

Rincón-Iglesias, M. et al. Sustainable fully inkjet-printed humidity sensor based on ionic liquid and hydroxypropyl cellulose. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 17, 32680–32690 (2025).

Li, X. et al. A nanocellulose-based flexible multilayer sensor with high sensitivity to humidity and strain response for detecting human motion and respiration. Int J Biol Macromol 266, 131004 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Highly sensitivity and wide-range flexible humidity sensor based on LiCl/cellulose nanofiber membrane by one-step electrospinning. Chem Eng J 503, 158018 (2025).