Abstract

Porous microneedles have attracted considerable attention as minimally invasive tools for interstitial fluid sampling and biomarker analyses. However, existing porous microneedle fabrication methods often suffer from low extraction efficiency, primarily because of the inherent trade-off between increasing porosity and maintaining sufficient mechanical strength. Herein, we present a novel approach for fabricating porous microneedles with controllable pore sizes and enhanced extraction performance. Monodisperse polylactic acid microspheres, produced via microfluidic techniques, are thermally bonded to form porous microneedles with interconnected pore networks originating from the connected voids between the microspheres. By precisely adjusting the microsphere diameter, we optimize the pore size to achieve high extraction efficiency while preserving structural integrity. Following surface treatment and bonding parameter optimization, the resulting porous microneedles exhibit sufficient mechanical strength to penetrate human skin and achieve an in vitro extraction rate of 0.95 μL/min per needle—the highest reported to date. Furthermore, porous microneedles are integrated with a colorimetric paper-based sensor for glucose detection, demonstrating a linear correlation between glucose concentration and the colorimetric response of the sensor. This work provides a promising tool for high-speed interstitial fluid extraction and expands the fabrication strategy for porous structures in biosensing applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microneedles (MNs) have attracted notable attention from researchers in many fields, such as biosensing and transdermal drug delivery1. MNs refer to an array of needles with microscale sizes, typically 500 μm to 1.5 mm in height. When applied to the human body, the MNs can penetrate the human skin in a minimally invasive manner and access the interstitial fluid (ISF) located in the skin dermis2. The painless access to the dermis layer makes MN use free of skin injuries, bleeding, or tissue damage, compared to conventional syringes. In addition, the application process does not require a trained medical expert, making MNs a promising alternative for biomedical applications compared with other ISF access methods. The ISF surrounding cells and tissue exchanges molecules with blood at the capillaries, which brings it similar biomarker composition and related biomarker concentration to that in blood2. For example, the ISF glucose concentration is highly correlated to that in blood with close concentration value and a 15-min lag time in case of rapid concentration change, which has been widely used for glucose level monitoring in human health management3. To meet the demands of various applications, different types of MNs have been developed with functionalized structures, including solid, coated, hollow, dissoluble, swellable, and porous types. Among MNs with diverse characteristics, hollow4, swellable5, and porous6 MNs have been widely applied for sampling ISF for biomarker analysis. Hollow MNs with a hollow channel inside the needle extract ISF by capillary force along the channel or through external negative pressure. However, the creation of channels inside microscale structures adds cost and complexity to the fabrication process. At the same time, the clogging issue inside the channel during its usage still exists7. Swellable MNs, usually made with hydrogel materials, can penetrate human skin and swell upon ISF extraction. However, biomarker analysis using swellable MNs involves a post-processing step to recover the sample fluid stored in the MNs after ISF collection, which limits the widespread use of swellable MNs for onsite ISF sampling and further biosensing applications8.

Porous MNs refer to needles with porous structures created on the surface or throughout the needle body. Using these micro or nanoscale pores, porous MNs can extract ISF via capillary force after skin penetration, and biomarker analysis can be performed on-site through surface functionalization9 or an integrated sensor10. Many researchers have focused on porous MN fabrication for ISF sampling and subsequent biomarker detection in various ways. The porogen leaching method is one of the most popular choices because removing the porogen from the bulk directly and effectively creates a porous structure. Lee et al. fabricated a porous poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) MN array with a paper substrate for glucose detection10. Salt particles served as the porogen and were mixed with the PLGA powder at a high temperature. The mixture was transferred to a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) female mold and fused with a paper base before porogen removal. The porogen ratio was regulated to change the MN porosity and increase the extraction ability of the porous MNs. Li et al. developed a mesoporous MN-based wearable system for diabetes sensing and treatment11. The porogen polyethylene glycol (PEG) was mixed with poly (glycidyl methacrylate) (PGMA) material, followed by UV crosslinking and porogen leaching in methanol solution. The porosity of the MNs was also tuned by regulating the porogen ratio and was fixed after optimization based on the mechanical strength for porcine skin penetration and molecule diffusion rate evaluation. The porous MNs were then coupled with reverse iontophoresis for electrochemical glucose detection and iontophoretic insulin delivery for diabetes management. Bao et al. fabricated porous polylactic acid (PLA) MNs using single emulsion method with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) as surfactant12. The MNs made of PLA and PVA were bonded after heat treatment with yellow change, which was attributed to polyene fractions in PVA chains. The porous MNs were integrated with a lateral flow immunoassay for the detection of corona virus antibodies, but the PVA material maintaining MN shape could be dissolved in water upon ISF extraction during practical use. Other methods, such as the phase separation method13 and freeze-drying method14, have also been used to create porous MNs for ISF sampling and biomarker detection.

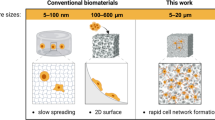

However, the current porous MN fabrication faces the problem of low extraction ability compared to other types of MNs for ISF sampling, which is attributed to two factors. First, the biodegradable materials used to create porous structures with microscale size are quite limited, such as PLGA10 and PGMA11, of which the material hydrophilicity is poor and can hardly provide sufficient capillary force for porous MN to extract fluid. Moreover, the pores created in the porous MNs were poorly connected and randomly distributed throughout the matrix. Although porous structures have been realized in various ways, the connection of the pore network has not been considered sufficiently, which dominantly affects the fluid extraction ability. Previous studies have attempted to control the porosity of porous MNs to create connected channels; however, the trade-off between mechanical strength and extraction ability remains challenging when regulating MN porosity15.

In this study, we fabricated porous MNs through the thermal bonding of monodisperse microspheres prepared using microfluidic technology. Biodegradable PLA microspheres were packed and bonded to create porous structures, and the void network between spheres formed interconnected channels in porous MNs after bonding under optimized conditions. Pore size is defined by the width of void channels between the packed microspheres, which is deviated from traditional definition (typically pore diameter). By adjusting the size of the microspheres using microfluidic technology, the MN pore size, in another word the channel width between microspheres, was controlled instead of porosity to increase the extraction ability of porous MNs. In addition, surface treatment using hydrophilic PEG was implemented to increase the capillary force provided by the porous structure. As a result, this study solved two challenging problems faced by porous MN fabrication and achieved the highest in vitro extraction ability compared to previous porous MNs for ISF sampling. Finally, the porous MNs were bonded to a diffusion layer and integrated into a colorimetric paper sensor for glucose detection. A linear relationship between the glucose concentration and color change of the paper sensor was confirmed using an artificial skin model.

Results and discussion

Porous MN fabrication using monodisperse microspheres prepared by microfluidic technology

Figure1 illustrates the overall process for porous MN fabrication using PLA microspheres prepared by microfluidic technology. First, we generated uniform microdroplets using the flow-focusing method with a microfluidic chip. The dispersed phase was PLA dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM), and the continuous phase was an aqueous solution of PVA. PLA was chosen as a low-cost, biodegradable, and biocompatible material compared to other kinds of materials. The degradation products of PLA material like carbon dioxide and lactic acid can be excreted in the urine and breath, which makes the PLA material widely applied in biomedical applications like drug delivery and tissue engineering with great biocompatibility and biodegradability16. And the low price of PLA material can limit the mass production cost of porous MNs in this work, which makes them advantageous as use-and-dispose management tools for cost-effective pre-diagnostic diabetes. PVA served as a surfactant to avoid microdroplet coalescence during generation17. Next, the generated microdroplets were solidified into PLA microspheres by evaporating DCM in the microdroplets, followed by removal of PVA on the sphere surface (Fig. S1). The obtained PLA microspheres were filled into a PDMS mold and thermally bonded in a convection oven to fabricate porous MNs. The pores in the MNs originated from the voids among the spherical microspheres, which could form a continuous network of interconnected channels in the porous structure for fluid extraction. The pore size between the microspheres was controlled by changing the size (diameter) of the microspheres to regulate the extraction ability of the porous MNs.

The generation of PLA microdroplets using microfluidic technology is shown in Fig. 2a. The dispersed and continuous phases encountered at the cross-section of the microfluidic chip formed uniform microdroplets at the interface between the two immiscible phases. By manipulating the continuous phase flow rate (Qc) and dispersed phase flow rate (Qd), the fluid viscous force was varied to change the diameter of generated microdroplets and thereby obtain microspheres of different sizes. The continuous phase flow rate was regulated from 60 μL/h to 3000 μL/h and the dispersed flow rate was regulated from 30 μL/h to 300 μL/h. The dispersed phase was a 1 wt% PLA/DCM solution, and the continuous phase was a 5 wt% PVA solution. As a result, the microdroplet diameter (Dd) decreased with the flow rate ratio (Qc/Qd) and the relationship followed the equation: Dd = A (Qc/Qd)B, where A = 161.56±6.86, B = −0.32 ± 0.01 (R2 = 0.975). The value of A could be varied by changing the microfluidic chip dimensions, such as the channel height at the cross area, and the exponent B was close to that in a previous study on microdroplet generation using a flow-focusing device18.

a Microdroplet generation with controllable size by regulating the flow rate ratio of the continuous phase to dispersed phase. Scale bar, 100 μm. b Microsphere diameter after solvent removal of microdroplets and SEM images of microspheres with diameters ranging from 10 μm to 40 μm. Scale bars, 20 μm. c Size distribution and optical image of monodisperse microspheres with a diameter of 10 μm. Scale bar, 100 μm. d Optical image of porous MNs. Scale bar, 500 μm. e SEM image of single MN made with 10 μm microspheres (scale bar, 200 μm) and MN surface composed of bonded microspheres (scale bar, 10 μm). f Dimensions of porous MNs fabricated using microspheres with different diameters

The microdroplets were solidified after DCM removal and PLA microspheres were obtained (Fig. 2b). The sphere diameter after solidification depended on the initial droplet size. The shrinkage ratio from the microdroplet diameter to the microsphere diameter was 27.95% (R2 = 0.998) for droplet generation using the 1% PLA/DCM solution. The same shrinkage ratio, regardless of microdroplet size, originated from the fixed mass fraction of PLA in the dispersed phase solution under the same evaporation conditions, which made the microsphere size controllable. The microsphere size was controlled and varied by changing the conditions, but in each case, the microspheres exhibited uniform sizes with low coefficient of variation (CV). The example in Fig. 2c showed the size distribution and optical image of PLA microspheres with an average diameter of 10 μm. The microsphere diameter had the CV of 3.76%, indicating a high monodispersity of sphere size19. Microspheres with a wider range of diameters were prepared by varying the shrinkage ratio with different dispersed phase concentration. As a result, monodisperse PLA microspheres with controllable sizes were obtained for the fabrication of porous MN.

PLA microspheres were then thermally bonded in a convection oven with pressure applied on top of the PDMS cover to fabricate porous MNs. In terms of bonding conditions, it was found that bonding at temperature over 180 °C led to the melting of PLA microspheres. Simultaneously, a temperature below 120 °C was not sufficient for complete bonding of spheres, which resulted in the breakage of the MN array during peeling off (Fig. S2). The applied pressure was necessary to maintain intimate contact between the microspheres during bonding. However, high pressure resulted in the deformation of the microspheres within a short time, regardless of the bonding temperature, which squeezed the pores between the microspheres, leading to the loss of pore connectivity (Fig. S3). Finally, the bonding conditions were set as 140 °C and 15 kPa for 60 min, under which the porous MNs were successfully fabricated and could be peeled off from the PDMS mold without breakage. It should be noted that the optimal bonding conditions for porous MNs made with spheres of various sizes should be different because the sphere packing situation and deformation under heat transfer may vary depending on the sphere size20. Thus, the bonding conditions were first kept the same to compare the porous properties and extraction performance of porous MNs made using spheres of different diameters. Parameter optimization after fixing the sphere size was also conducted and is presented later in this work. As shown in Fig. 2d, e, 5 × 5 MNs with pyramidal shapes were fabricated on one patch and were composed of PLA microspheres bonded at the sphere interface. The MNs were designed to have pyramidal shape to achieve high mechanical strength and promote human skin penetration. It was reported that MNs with pyramidal shape had higher mechanical strength with better performance in failure force measurement and higher critical bulking load in numerical simulation when compared to MNs with other geometries like conical shape21. Also, it was pointed out that the pyramidal MNs had lower needle stress during skin penetration and larger penetration depth into porcine skin when compared to MNs in other shapes like hexagonal shape22. Thus, pyramidal MNs were fabricated in this work to obtain high mechanical strength with low needle stress for human skin penetration. The length of porous MNs made using 10 μm spheres was 1140 ± 13 μm, and the base width was 601 ± 11 μm with a tip diameter of 26 ± 4 μm. When fabricating porous MNs using spheres with different diameters, the pyramidal shape and base width were maintained, but the MN length decreased with an increase in the tip diameter when larger microspheres were used (Fig. 2f). For example, the MNs made using 40 μm spheres had a length of 982 ± 21 μm with a tip diameter of 52 ± 12 μm. The difference in dimensions was attributed to the fact that smaller microspheres were filled into the tip of the PDMS mold more easily than large ones. Large microspheres left a vacant part at the female mold tip during packing, resulting in shorter needles with blunt tips after bonding. The MN length from 982 μm to 1140 μm was sufficient to pierce skin for ISF extraction considering penetration ratio due to skin elasticity and epidermis thickness23. But the different needle tip diameter especially blunt needle tip with large cross-sectional area would influence insertion into human skin during application24. Thus, microspheres with diameters over 40 μm were not used for MN fabrication and were excluded from further analysis.

Improvement of porous MN extraction ability by regulating porous structure properties

After porous MN fabrication, porous structure properties such as porosity and pore size were studied to improve the extraction ability of porous MNs. Fluid extraction was driven by the capillary force generated from the microchannels in the porous MNs. The capillary rise of liquid in microchannels can be calculated based on the equation below using Jurin’s law25. The h represents the height of capillary rise driven by the force, γ is the surface tension of sample fluid (water) to air, which is about 0.072 N/m in this work at room temperature26. The ρ refers to the water density and g is the gravitational acceleration. From Eq. 1, the liquid rise under capillary force is proportional to the cosθ/r, where θ is the water contact angle (WCA) of the channel surface material and r is the channel size in porous MNs.

In this study, we regulated the fundamental factors, including channel size and surface hydrophilicity to increase the capillary force generated by the porous structure and improve the porous MN extraction ability. The porous structure was achieved by packing and bonding monodisperse microspheres together. Unlike previous studies, which created conventional pores in MNs that served as fluid extraction channels, the porous MNs in this study used the continuous voids among microspheres as the interconnected channels for fluid extraction. In our method, the channel size in porous MNs was controlled and could be regulated to achieve high extraction ability by simply changing the microsphere size using microfluidic technology. Moreover, the MN fabrication through sphere bonding instead of pore creation guaranteed the connectivity of microchannels because the spherical shape of the microspheres and voids among them were maintained under optimized bonding conditions. Taking advantage of the connectivity between channels, the channel surfaces of porous MNs were modified with hydrophilic material to decrease the WCA and improve the capillary force for fluid extraction.

No pores surrounded by solid material were observed in this study theoretically and experimentally. Thus, the pore size was defined as the width of the channels between the microspheres that generated capillary forces for fluid extraction. The pore size was measured by analyzing the neighbor distance of the microspheres using the ImageJ software under SEM observation of the porous MN surface27. Consequently, the average pore size decreased from 7.17 μm to 1.12 μm as the sphere size decreased from 40 μm to 5 μm (Fig. 3a). This is because packing and bonding smaller spheres could decrease the channel width between them owing to the overall narrowed void among small spheres.

a–c Pore size distribution (a), extraction ability (b), and porosity (c) of porous MNs fabricated using monodisperse microspheres of different sizes. d Comparison of porous MN extraction ability after surface modification and SEM images of MN surface before (left) and after (right) PEG treatment. Scale bars, 10 μm. e WCA change of solid and porous PLA surface after PEG treatment. f Porous MN extraction ability during long-term storage after surface treatment

The extraction ability of the porous MNs was evaluated based on the rate of porous MN extracting the sample fluid from the artificial skin model. The MN array was saturated with the extracted fluid after application to the skin model. The fluid volume in the saturated MNs was divided by the saturation time to calculate the extraction rate of each MN array. As a result, the porous MN extraction ability increased as the sphere size decreased from 40 μm to 10 μm (Fig. 3b), which was attributed to the higher capillary pressure driven by the narrowed channel width. However, the highest extraction ability reached 4.04 μL/min for porous MNs made with 10 μm spheres and then decreased when using smaller spheres despite the narrowed channel width, which was attributed to the loss of pore connectivity according to the porosity measurement. The MN porosity was evaluated using a measurement kit (Fig. S4) based on the Archimedes principle28. Open porosity refers to the pores that are connected to create continuous channels from the MN surface to the internal porous structure for fluid extraction. The total porosity includes open porosity and closed porosity meaning the pores that were closed and trapped by solid materials. As a result, the open porosity was close to total porosity for MNs made with spheres larger than 5 μm, indicating almost all the pores were connected with each other, making a continuous network of interconnected channels throughout the MNs for fluid extraction (Fig. 3c). The high channel connectivity originated from the MN fabrication through the packing of monodisperse microspheres and was well maintained during thermal bonding. However, obvious difference between open and total porosity was found for MNs made with 5 μm spheres. The high surface-to-volume ratio of 5 μm spheres made them easily influenced by heat transfer. The deformed spheres squeezed the pores between them and led to the loss of pore connectivity with reduced extraction ability (Figs. S5 and S6). Mixing microspheres of different sizes, such as 5 μm and 10 μm (1:1), did not solve the problem because the existence of 5 μm sphere still influenced pore connectivity in porous MNs under the same bonding condition (Fig. S7).Lower bonding temperature and pressure were also tested, but loss of pore connectivity existed even under the conditions that led to failure of MN fabrication, indicating spheres smaller than 10 μm were not suitable for MN fabrication using the thermal bonding method. Therefore, microspheres with 10 μm diameters were finally selected for MN fabrication with interconnected channels as well as high extraction ability for further experiments.

In addition to regulating the channel size, the channel surface of the porous MNs was modified to improve hydrophilicity and increase the capillary force for fluid extraction (Fig. 3d). Plasma and PEG treatments, which are widely applied for surface modification, were tried, and MN extraction ability after treatment was evaluated29,30. The results showed that plasma treatment reduced the extraction ability compared to the untreated sample. It was found that only the surface of the porous MN array exposed to plasma was influenced, resulting in increased surface hydrophilicity. The extracted liquid was stopped from penetrating the entire MN array at the interface between the exposed surface and unexposed inner parts (Fig. S8), which was attributed to the capillary pressure difference between the two parts.

In contrast, the surface treatment using a PEG solution was easily implemented throughout the porous MN array, taking advantage of the connected channels. And the PEG surface coating would not change the biocompatibility of porous MNs applied into human skin since both PLA and PEG materials have been reported with excellent biocompatibility for various biomedical applications31. As shown in Fig. 3d, the porous MN extraction ability increased from 4.04 μL/min to 7.57 μL/min after PEG surface treatment, and there was no obvious difference on MN surface or PEG membrane left between spheres that would influence the pore connectivity. The increase in extraction ability was attributed to the PEG molecules left on the channel surface, which resulted in a higher capillary force under the same channel size. The WCA of solid and porous PLA were measured to compare the surface hydrophilicity before and after treatment. The WCA of solid PLA surface decreased from 79.6° to 34.2° after PEG treatment, and the contact angle of porous surface decreased from 95.3° to 41.5° (Fig. 3e). We concluded that the WCA of the porous surface was higher than that of the solid surface because of the air existing in porous structure. In the Cassie state, the air pocket existed between the liquid and roughened porous surface increased the apparent contact angle regardless of the original wettability of solid surface32. Consecutively, the porous MNs were stored under ambient conditions after surface treatment and tested for extraction ability after different periods of storage. It was found that the surface treatment effect lasted for 90 days, with no obvious change in extraction ability, indicating a stable hydrophilicity improvement for porous MNs after long-term storage (Fig. 3f).

Improvement of porous MN mechanical strength for skin penetration

To evaluate the mechanical strength of the porous MNs for human skin penetration, the MNs were applied to porcine skin for in vitro testing. After penetration, the porcine skin was found to be pierced with puncture dots left on the skin stained with methylene blue, but the needle body was also broken and left inside the skin (Fig. 4a). When subjected to a compression test, the porous MNs exhibited an average failure force of 180.0 mN (Fig. 4b), which was higher than the force required for human skin penetration33. Thus, the MN breakage in porcine skin was attributed to the shear force received by the needle body during skin penetration. To mimic the real situation of applying MNs onto human skin, the porous MNs were applied to porcine skin by finger press, which could not provide a strictly vertical force like that in the compression test, leading to the generation of a shear component during force application and finally to the breakage of MNs.

a Optical images of porcine skin and MNs after in vitro skin penetration test before and after mechanical strength improvement. Scale bars, 500 μm. b Failure force curve and mean value of porous MNs before and after mechanical strength improvement. c MN porous surface, pore size distribution, and extraction ability before and after mechanical strength improvement. d MN porosity before and after mechanical strength improvement. e Failure force curve and mean value of porous MNs before and after PEG treatment. f Comparison with previous work on porous MN fabrication for ISF sampling

Therefore, the mechanical strength of porous MNs was improved by optimizing the bonding conditions after fixing the sphere size. It was found that the force to bond microspheres came from both the applied pressure and thermal expansion of the female mold during heat treatment34. Higher temperature not only caused more expansion of the PDMS mold with higher force applied to the spheres, but also triggered the polymer chains on the sphere surface to diffuse across the interface between the spheres and bond them together35. The applied pressure was found to mainly affect the sphere deformation on the MN substrate part, with almost no influence on the spheres in the needle body, according to COMSOL simulation (Fig. S9). Therefore, the bonding temperature was increased to 170 °C to apply a higher bonding strength between the spheres while preventing the melting of the PLA material. The applied pressure was decreased to 3 kPa to reduce the pressure on the array substrate and avoid excess sphere deformation at high temperature. As a result, the porous MNs fabricated under optimized conditions could penetrate porcine skin without breakage with almost no length change after penetration as shown in Fig. 4a. The failure force of the porous MNs after mechanical strength improvement increased from 180.8 mN to 404.4 mN (Fig. 4b). The improvement of mechanical strength was attributed to the larger bonding interface between microspheres formed under high bonding temperature of 170 °C compared to that under 140 °C according to SEM observation (Fig. 4c). The average pore size of MNs was 1.75 µm, which was slightly higher than that before parameter optimization since some small pores between microspheres were filled by the sphere deformation under high temperature while most pores were still maintained with reduced bonding pressure. The filled pores led to lower extraction ability with decreased total porosity from 41% to 38%, but the interconnectivity of channels between microspheres was preserved according to the porosity measurement because most pores were still maintained to form connected channels for fluid extraction (Fig. 4d). The average pore size of MNs after optimization was 1.75 µm, which was the width of channels between microspheres for ISF extraction with biomarkers. Considering the width of channels for biomarker extraction, biomarkers with molecule size smaller than the pore size can be extracted theoretically. Most ISF biomarkers for health monitoring such as potassium ions, sodium ions, glucose, lactate, and proteins like insulin and Immunoglobulin G have the molecule sizes of several nanometers, which can be extracted and transported through the connected channels in porous MNs for detection. After PEG treatment, the MNs with improved mechanical strength had increased extraction ability close to those without strength improvement. In addition, PEG treatment did not affect the mechanical strength of the porous MNs (Fig. 4e). As a result of the optimization, the obtained porous MNs with improved mechanical strength and surface treatment could penetrate porcine skin without breakage and with high extraction ability for ISF sampling, as shown the Video S. After extraction and drying, the MNs also showed stability that no obvious change was found on the porous surface under SEM observation and the MN failure force was the same as that before extraction, indicating stable mechanical property and porous structure during extraction, which showed the possibility for long-term continuous usage in the future (Fig. S10).

Finally, the porous MNs were applied to a human skin model containing artificial ISF for extraction evaluation and compared with previous work on porous MN fabrication for ISF sampling. When applied using 1 N force, the porous MN array was saturated within 30 s and the average extraction volume after saturation was 11.82 ± 0.55 μL. As a result, the porous MNs in this work realized the highest in vitro extraction ability of 0.95 ± 0.04 μL/min for each needle with sufficient mechanical strength for human skin penetration (Fig. 4f)10,12,13,36,37,38.

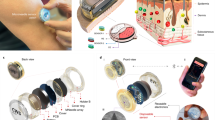

Glucose detection using porous MN integrated paper sensor with diffusion layer

After evaluating the porous MNs, we integrated them with a colorimetric paper sensor to develop a microneedle array patch (MAP) for glucose detection, with a diffusion layer to achieve a uniform color change for analysis. A colorimetric paper sensor was prepared by immobilizing glucose oxidase (GOx) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) on 5 mm diameter filter paper with 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) as the chromogenic reagent39. Glucose in the extracted fluid is oxidized to gluconic acid with hydrogen peroxide generation. In the presence of peroxidase, TMB is oxidized by the hydrogen peroxide with blue color change on colorimetric paper sensor. The degree of color change indicated the amount of TMB oxidized by hydrogen peroxide, which showed the glucose concentration in the extracted fluid (Fig. 5a). To develop the MAP for glucose detection by combining paper sensors and porous MNs, three different methods were evaluated, as shown in Fig. 5b. In Group 1, the paper sensor was directly contacted with the MN array by fixing on top. In Group 2, a fluidic channel was created to transfer the extracted fluid from MN array to paper sensor40. In Group 3, a diffusion layer made of filter paper was bonded to porous MN array and integrated with paper sensor to drive the diffusion of extracted fluid. The MAPs prepared using different methods were evaluated by applying each sample to a skin model containing 5 mM glucose and optical images were captured after 5 min. It was found that the saturation volume for three methods was different because of varied structure and components, but the paper sensor showed color change within 1 min in all cases, indicating high extraction ability of porous MNs. And the application time for three groups was kept the same for color change evaluation. The color intensity was calculated based on the grayscale value of the blue channel image after RGB separation using the ImageJ software. The uneven distribution of the color change on the paper sensor was analyzed using the standard deviation of the color intensity for each sensor sample.

As shown in Fig. 5c, the control group showed a color change in the paper sensor after pipetting a 5 mM glucose solution. The color densities of the three methods showed slight differences between each other but were all lower than that of the control group, as the porous MN extraction from the skin model took longer time than pipetting the solution, resulting in a shorter reaction time for the paper sensor color change. Regarding the evaluation of uneven distribution, the color change of Group 1 showed a dot-like distribution, and that of Group 2 showed coffee ring phenomena. The uneven distribution of color change in the two groups was attributed to the fact that the fluid extracted by MNs was not transferred evenly to the paper sensor, which led to the lateral flow of fluid on the paper sensor41. In Group 1, MN penetration was considered to influence the results. Some MNs on the array had a larger exposed area after penetrating the aluminum foil of the skin model. It was considered that these MNs had a higher extraction speed, and the fluid extracted by these needles was transferred directly onto paper sensor, reaching the paper sensor faster than other parts. In Group 2, the fluid in the MNs was transferred to the paper sensor via a fluidic channel, and the fluid in the channel reached the central part of the paper sensor before reaching the surrounding part. Consequently, lateral flow was generated from the wet part to the dry part of the paper sensor, causing the migration and uneven distribution of the enzyme on the sensor, which led to an uneven color change after the reaction42. The uneven distribution of color change in the above methods makes it difficult to analyze or distinguish the color intensity for different glucose concentrations, which hampers the sensing accuracy and repeatability43. In contrast, the MAP in Group 3 showed an even distribution compared to the previous two groups. It was considered that the fluid extracted by MNs was first transferred to the diffusion layer, allowing for lateral flow, and then gradually diffused from the diffusion layer to the paper sensor via the paper-paper interface. As the diffusion layer prevented lateral flow on paper sensor and avoided enzyme migration, uniform color changes were obtained compared to the other two methods. Therefore, the MAP in Group 3 was utilized for glucose detection with even color distribution compared to other two configurations. The whole patch was applied to skin model prepared using artificial ISF with colorant to visualize the wetting of paper sensor during extraction. The weight change of sensor patch after 1 min extraction was measured to calculate the extraction volume and optical image was taken from patch back side. As a result, the sensing patch collected 21.03 ± 1.34 µL sampling fluid in 1 min, which was much higher than the saturation volume to fill porous MNs and diffusion layer (17.87 ± 0.88 µL). And obvious color change was observed on whole paper sensor after 1 min extraction, indicating sufficient extraction volume to wet the paper sensor for glucose detection (Fig. S11).

Finally, the MAP with a diffusion layer was applied to a skin model with different glucose concentrations (1–20 mM) for pre-diagnosis of diabetes, and the color intensity was analyzed (Fig. 5d). As a result, the color intensity increased linearly with the glucose concentration of the skin model with a detection limit of 0.41 mM, indicating the potential of the sensor patch for ISF glucose detection. The developed porous MAP with a paper sensor is expected to simplify the fabrication process of ISF biomarker analysis devices and realize the low-cost, simple, and fast pre-diagnosis for diabetes management. Moreover, multiple biomarker analyses can be realized based on similar detection mechanism through other enzyme immobilizations like cholesterol oxidase. Despite the promising results mentioned above, the flexibility of porous MNs especially the substrate part should be improved in the future to fit the MN sensor patch onto the elastic human skin for continuous and stable ISF sampling. Glucose detection methods with robustness to environmental factors, such as brightness, should also be considered to contribute to human health management and point-of-care devices.

Conclusion

In this study, we fabricated porous MNs with controllable pore sizes and high extraction ability through the thermal bonding of monodisperse microspheres. The porous structure was realized by packing and bonding PLA microspheres, and the pores originated from the voids between the bonded microspheres. By regulating the size of the microspheres using microfluidic technology, the pore size in porous MNs was controlled, and the pore connectivity was guaranteed with a continuous network of interconnected channels in the porous MNs. The channel surfaces of the porous MNs were treated to improve their hydrophilicity and increase the capillary force for fluid extraction. After mechanical strength improvement by optimizing the bonding conditions, the porous MNs could penetrate porcine skin without breakage. The results indicated that our work solved the issues faced by current porous MNs and improved the MN extraction ability using hydrophilic and interconnected microchannels with controllable size, which realized the highest in vitro extraction ability compared to previous studies. The obtained MNs were integrated into a colorimetric paper sensor with a diffusion layer for glucose detection. The MN-integrated paper sensor showed a uniform color change, and the color intensity increased linearly with the glucose concentration when tested using an artificial skin model. It was expected that our work on porous MN fabrication by equal sphere bonding with interconnected channels may expand the choice of MN materials and break the limitation of surface functionalization on microscale porous structures.

Materials and methods

Preparation of microspheres

To prepare monodisperse microspheres, PLA microdroplets were first generated by using microfluidic devices (Fig. S12). The detailed sphere preparation process was studied in our previous work44. In brief, the dispersed phase was prepared by dissolving PLA material (16609, Mutoh Industries LTD., Tokyo, Japan) in DCM (135-02446, Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), and the continuous phase was prepared by dissolving PVA (363073, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 90 °C DI water under stirring at 1000 rpm. The microfluidic chip (3200433, Dolomite Microfluidics, Boston, MA, USA) had the dimension of 105 μm × 105 μm at cross area with a channel height of 100 μm. The pressure applied to the fluidic chamber (3200016, Dolomite Microfluidics, Boston, MA, USA) was regulated to vary the flow rates of the continuous and dispersed phases. Microdroplets were generated at the cross area in the microfluidic chip and collected into a beaker through the outlet. DCM in the microdroplets was removed to solidify the microdroplets into spheres by gently stirring the microdroplet solution at 150 rpm45. The PVA left in microsphere solution was removed by centrifugation and rinsing with DI water. Finally, the PLA microsphere powder was obtained after sphere drying under vacuum and stored at room temperature before use.

Fabrication of porous MNs

To fabricate porous MNs using microspheres, a metal master mold was firstly made by wire electrical discharge machining. The master mold had 5 × 5 pyramidal needles on it and each needle was 1150 μm in length with the pitch of 1000 μm. PDMS (DOWSIL SILPOT 184, Dow Chemical Company, Midland, MI, USA) mixture was prepared by mixing the base material and curing agent at the weight ratio of 10:1. The mixture was poured onto the master mold and vacuumed to remove the bubbles. After curing at 90 °C for 1 h, the PDMS female mold was peeled off from the master mold. To apply pressure to the microspheres during thermal bonding, another piece of PDMS block was prepared using a 3D printed negative mold. The dimensions of the PDMS block were designed to be smaller than the inner size of the PDMS female mold. Considering the expansion of the PDMS block during bonding, a 1 mm distance was left between the PDMS block and inner wall of the PDMS female mold after placing the block on the microspheres34.

For each MN array, 20 mg of PLA microspheres were dispersed into 200 μL DI water and transferred into PDMS female mold. Degassing and ultrasonication were applied for 5 min to remove bubbles and fill the microspheres into the PDMS female mold. After drying at room temperature, the PLA spheres were covered with a PDMS block. To bond the microspheres together, a programmable convection oven (OFP-300V, AS ONE Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was used and preheated to the bonding temperature. The applied pressure was provided by a preheated metal block placed on top of the PDMS block. After bonding for fixed time and cooled down to 30 °C in oven, the metal block and PDMS block were removed, and porous MN array was peeled off from PDMS female mold. The porous MNs were observed using optical microscopy (Stemi 305, Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) to measure the MN dimensions, such as MN length and tip diameter.

MN pore size and porosity measurement

To measure the pore size of the porous MNs, the MN surface was observed under SEM (JSM-5600LV, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed using ImageJ software. The pore size in this study was interpreted as the channel width between microspheres; therefore, the neighbor distance of microspheres on the MN surface was measured using a plugin in the software27. The sphere packing situation of different needle parts was found to be slightly different and the needle base had looser packing than the tip part on the surface. Therefore, the same part of the MN surface was observed, and the mean value of 2000 distances measured from ten different MNs was obtained to calculate the average pore size.

The MN porosity was measured using the water immersion method based on Archimedes principle28. The porosity measurement kit (Secura 125-1S, Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany) was set up as shown in Fig. S4. In addition to the weight measurement function, the kit had a loop connected to a copper wire hung on the arm of the balance to suspend the specimen in water and prevent it from sinking to the bottom. The dry weight of the porous MN array was first measured and recorded as D, which refers to the weight of the solid part in the porous MN array to calculate the solid volume in the porous structure based on the material density, which was 1.24 g/cm3 for the PLA in this study. The sample was then immersed in water for 1 h to ensure that water filled all the open pores connected to the porous MNs. As the porous MNs were saturated with water, the saturation weight was measured as S after using cotton wiper to remove the water left on the sample surface to calculate the volume of open pores in the porous structure. Finally, the porous MN was placed in a loop connected to the wire system of the balance, and the weights of the wire system before and after placing the sample in water were measured as Wwire and Wsus, respectively. The difference between them was the weight of the suspended porous MN array, which was affected by the combined effect of gravity and buoyant force due to water immersion and was used to calculate the volume of closed pores in the porous MNs. The porosity of the porous MNs was calculated using the parameters measured above based on the following equations:

Characterization of porous MN extraction ability

To evaluate the porous MN extraction ability, an artificial skin model was prepared using an agarose hydrogel by dissolving 1 wt% agarose powder (NE-AG01, NIPPON Genetics Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in DI water at 90 °C under gentle stirring and cooling to room temperature46. The prepared agarose hydrogel was stored under 4 °C with parafilm sealing until usage. When optimizing the MN fabrication parameters, no foil was covered on the hydrogel during the extraction test because MNs made with different parameters, such as sphere size and bonding temperature, may have different mechanical strengths, which may lead to different foil penetration ratios and influence the comparison results of the extraction ability. Thus, the MN array was applied to the agarose hydrogel directly under a gentle force of 30 mN to keep the continuous extraction against hydrogel elasticity47. After optimizing and improving the porous MN extraction ability, the MN array was finally evaluated for comparison with previous studies. To mimic the real situation when applied to human skin, the porous MN was applied to agarose hydrogel covered with aluminum foil under 1 N force. The agarose hydrogel was prepared by dissolving 1 wt% agarose powder (NE-AG01, NIPPON Genetics Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and 1 wt% red colorant (4901325001245, KYORITSU, Tokyo, Japan) in artificial ISF. The artificial ISF was prepared by mixing 0.7 mM magnesium sulfate (137-12335, Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), 2.5 mM calcium chloride (030-25305, Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), 3.5 mM potassium chloride (32326-01, Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan), 123 mM sodium chloride (S9888-500G, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 5.5 mM glucose (0400515, Hayashi Pure Chemical Ind., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), 7.4 mM sucrose (192-00012, Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (340-08233, Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), and 1.5 mM sodium dihydrogen phosphate (197-09705, Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) considering the composition of human ISF48,49. The MN extraction ability was obtained based on the measurement of saturation time and saturation volume. Porous MN array was applied to skin model and observed from backside. The saturation time was determined as the time for whole MN array to turn red, which indicated that the whole array was filled by the extracted fluid. And the MN array weight change at saturation time was measured to obtain the saturation volume. The saturation volume was divided by saturation time and needle numbers on one patch to calculate the fluid extraction rate of porous MNs for comparison with previous work. The adding of 1 wt% red colorant in hydrogel for extraction visualization was proved to have no influence on extraction rate measurement by comparing the MN extraction volume in same time to the hydrogel without colorant (Fig. S13). To visualize the extraction process, the porous MNs were fixed to a controllable moving stage (SGAM26-100, SIGMA KOKI CO., LTD., Tokyo, Japan) and penetrated into agarose hydrogel containing red colorant. The MNs were moved downwards after contact with hydrogel to realize penetration depth of 600 μm, which was 60% of needle length to mimic the penetration into human skin19 and the visualized extraction process was recorded (Video S).

Hydrophilic surface treatment and WCA measurement

In terms of plasma treatment, porous MNs were placed upwards and exposed to 45 W plasma (YHS-R, SAKIGAKE Semiconductor Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) for 3 min. For PEG treatment, porous MNs were immersed in a 5% w/v PEG ethanol solution for 30 min, followed by drying under vacuum to remove the residual solvent. The WCA measurements of the solid and porous PLA surfaces were performed using a goniometer with a video capture function (JC2000D1, Powereach, Shanghai, China). To measure the static contact angle using the sessile drop method, water droplet of 1 μL was added onto the PLA surface at room temperature and the contact angle was determined automatically by the software after image capture. Regarding the porous surface WCA measurement, the contact angle image was captured immediately after the water droplet application because the droplet started to diffuse into the porous structure especially for the one with PEG treatment. In each case, the average contact angle was obtained by measuring nine different positions from three different samples.

Mechanical test of porous MN

The mechanical strength of the porous MNs was evaluated using a compression test and an in vitro porcine skin insertion test50. The compression test was performed using a force measurement device equipped with a force gauge sensor (IMADA Co., Ltd., Toyohashi, Japan). The bottom of the MN array was fixed, and the force gauge moved down towards the tip of a single MN at a speed of 1.5 mm/min, with the force and displacement curves recorded simultaneously. As the force gauge moved and pressed the porous MN, the force recorded with displacement suddenly dropped upon needle failure, and the maximum force applied immediately before dropping was interpreted as the MN failure force. For in vitro skin penetration, the porcine skin was selected because of its similarity to human skin in terms of physiology and anatomy51. Porcine ear skin (K1270, Funacoshi Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was stored under −20 °C and kept at room temperature for 30 min before usage. The porous MNs were applied to porcine skin by finger press and removed, followed by staining using 10 mg/mL methylene blue solution (M9140, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) for 10 min. The solution remaining on the skin surface was then wiped away using ethanol and the skin with puncture holes was observed using an optical microscope (VH-5500, Keyence Co., Osaka, Japan).

Fabrication and evaluation of porous MN integrated paper sensor

The colorimetric paper sensor was prepared by cutting the same filter paper into circles with a diameter of 5 mm, considering the MN array size. A mixture of 250 mM trehalose dihydrate (T9449, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 100 U/mL GOx (G7141, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and 100 U/mL HRP (SRE0082, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 1× PBS (Nacalai Tesque, INC., Kyoto, Japan) and 4 μL solution was pipetted onto paper sensor. After drying at room temperature, 4 μL of 15 mM TMB (860336, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) methanol solution was pipetted and dried to obtain the chromogenic reagent. In Group 1, the paper sensor and MN array was combined by fixing the sensor onto the back of the MN array directly using adhesive tape. In Group 2, the paper sensor was adhered to a film on the top, and the MN array was attached to the bottom of the film using double-sided tape. A fluidic channel was created by making a hole with a 2 mm diameter in the center and subsequently filling it with hydrophilic cellulose powder (034-22221, Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan)40. In Group 3, a diffusion layer was created between the porous MNs and the paper sensor using the same thermal bonding method. Microspheres were filled into PDMS mold and a piece of filter paper (Grade 4, Whatman plc, Maidstone, UK) with 210 μm thickness was placed on microspheres, followed by the PDMS block covering on top to provide external pressure for thermal bonding. The bonding temperature and pressure were kept the same, but the bonding time was prolonged to 90 min to bond the microspheres and filter paper at the interface. The colorimetric paper sensor was finally attached to the top of the diffusion layer using adhesive tape.

A 5 mM glucose solution was prepared by dissolving glucose powder (0400515, Hayashi Pure Chemical Ind., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) in 1× PBS. Skin models with different glucose concentrations were prepared by dissolving glucose powder in an agarose solution during stirring. All the glucose detection results were obtained after five-minute application to skin models, and optical images were captured using digital camera (D5500, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The surrounding environmental factors, such as brightness, were controlled to obtain images under the same conditions for analysis.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Rad, Z. F., Prewett, P. D. & Davies, G. J. An overview of microneedle applications, materials, and fabrication methods. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 12, 1034–1046 (2021).

Friedel, M. et al. Opportunities and challenges in the diagnostic utility of dermal interstitial fluid. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 7, 1541–1555 (2023).

Thennadil, S. N., Rennert, J. L., Wenzel, B. J., Hazen, K. H., Ruchti, T. L. & Block, M. B. Comparison of glucose concentration in interstitial fluid, and capillary and venous blood during rapid changes in blood glucose levels. Diab. Technol. Ther. 3, 357–365 (2001).

Jiang, X. & Lillehoj, P. B. Microneedle-based skin patch for blood-free rapid diagnostic testing. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 6, 96 (2020).

Omidian, H. & Dey Chowdhury, S. Swellable microneedles in drug delivery and diagnostics. Pharmaceutics 17, 791 (2024).

Gao, G., Zhang, L., Li, Z., Ma, S. & Ma, F. Porous microneedles for therapy and diagnosis: fabrication and challenges. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 9, 85–105 (2022).

Aldawood, F. K., Andar, A. & Desai, S. A comprehensive review of microneedles: types, materials, processes, characterizations and applications. Polymers 13, 2815 (2021).

Fonseca, D. F. et al. Swellable gelatin methacryloyl microneedles for extraction of interstitial skin fluid toward minimally invasive monitoring of urea. Macromol. Biosci. 20, 2000195 (2020).

Bollella, P., Sharma, S., Cass, A. E., Tasca, F. & Antiochia, R. Minimally invasive glucose monitoring using a highly porous gold microneedles-based biosensor: characterization and application in artificial interstitial fluid. Catalysts 9, 580 (2019).

Lee, H., Bonfante, G., Sasaki, Y., Takama, N., Minami, T. & Kim, B. Porous microneedles on a paper for screening test of prediabetes. Med. Devices Sens. 3, e10109 (2020).

Li, X. et al. A fully integrated closed-loop system based on mesoporous microneedles-iontophoresis for diabetes treatment. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100827 (2021).

Bao, L., Park, J., Qin, B. & Kim, B. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM/IgG antibodies detection using a patch sensor containing porous microneedles and a paper-based immunoassay. Sci. Rep. 12, 10693 (2022).

Jing, H., Park, J. & Kim, B. Fabrication of a polyglycolic acid porous microneedle array patch using the nonsolvent induced phase separation method for body fluid extraction. Nano Sel. 6, e202400145 (2024).

Abe, H., Matsui, Y., Kimura, N. & Nishizawa, M. Biodegradable porous microneedles for an electric skin patch. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 306, 2100171 (2021).

Liu, L., Kai, H., Nagamine, K., Ogawa, Y. & Nishizawa, M. Porous polymer microneedles with interconnecting microchannels for rapid fluid transport. RSC Adv. 6, 48630 (2016).

Da Silva, D. et al. Biocompatibility, biodegradation and excretion of polylactic acid (PLA) in medical implants and theranostic systems. Chem. Eng. J. 340, 9–14 (2018).

Ekanem, E. E., Nabavi, S. A., Vladisavljević, G. T. & Gu, S. Structured biodegradable polymeric microparticles for drug delivery produced using flow focusing glass microfluidic devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 23132 (2015).

Ganán-Calvo, A. M. & Gordillo, J. M. Perfectly monodisperse microbubbling by capillary flow focusing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 274501 (2001).

Vladisavljević, G. T., Duncanson, W. J., Shum, H. C. & Weitz, D. A. Emulsion templating of poly (lactic acid) particles: droplet formation behavior. Langmuir 28, 12948 (2012).

Jimidar, I. S., Sotthewes, K., Gardeniers, H., Desmet, G. & van der Meer, D. Self-organization of agitated microspheres on various substrates. Soft Matter 18, 3660–3677 (2022).

Lee, J. W., Park, J. H. & Prausnitz, M. R. Dissolving microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Biomaterials 29, 2113–2124 (2008).

Loizidou, E. Z., Inoue, N. T., Ashton-Barnett, J., Barrow, D. A. & Allender, C. J. Evaluation of geometrical effects of microneedles on skin penetration by CT scan and finite element analysis. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 107, 1–6 (2016).

Chen, Y., Chen, B. Z., Wang, Q. L., Jin, X. & Guo, X. D. Fabrication of coated polymer microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. J. Control. Release 265, 14–21 (2017).

Römgens, A. M., Bader, D. L., Bouwstra, J. A., Baaijens, F. P. T. & Oomens, C. W. J. Monitoring the penetration process of single microneedles with varying tip diameters. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 40, 397–405 (2014).

Liu, S., Li, S. & Liu, J. Jurin’s law revisited: exact meniscus shape and column height. Eur. Phys. J. E 41, 1–7 (2018).

Meseguer, J. et al. Surface tension and microgravity. Eur. J. Phys. 35, 055010 (2014).

Haeri, M. & Haeri, M. ImageJ plugin for analysis of porous scaffolds used in tissue engineering. J. Open Res. Softw. 3, e1 (2015).

Gholami, S. et al. Fabrication of microporous inorganic microneedles by centrifugal casting method for transdermal extraction and delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 558, 299–310 (2019).

Morent, R., De Geyter, N., Desmet, T., Dubruel, P. & Leys, C. Plasma surface modification of biodegradable polymers: a review. Plasma Process. Polym. 8, 171–190 (2011).

Long, H. P., Lai, C. C. & Chung, C. K. Polyethylene glycol coating for hydrophilicity enhancement of polydimethylsiloxane self-driven microfluidic chip. Surf. Coat. Technol. 320, 315–319 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Biomaterials for inflammatory bowel disease: treatment, diagnosis and organoids. Appl. Mater. Today 36, 102078 (2024).

Ran, C., Ding, G., Liu, W., Deng, Y. & Hou, W. Wetting on nanoporous alumina surface: transition between Wenzel and Cassie states controlled by surface structure. Langmuir 24, 9952–9955 (2008).

Park, J. H., Allen, M. G. & Prausnitz, M. R. Biodegradable polymer microneedles: fabrication, mechanics and transdermal drug delivery. J. Control. Release 104, 51–66 (2005).

Zhang, G., Sun, Y., Qian, B., Gao, H. & Zuo, D. Experimental study on mechanical performance of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) at various temperatures. Polym. Test. 90, 106670 (2020).

Padhye, N., Parks, D. M., Trout, B. L. & Slocum, A. H. A new phenomenon: Sub-Tg, solid-state, plasticity-induced bonding in polymers. Sci. Rep. 7, 46405 (2017).

Takeuchi, K., Takama, N., Kinoshita, R., Okitsu, T. & Kim, B. Flexible and porous microneedles of PDMS for continuous glucose monitoring. Biomed. Microdevices 22, 1–12 (2020).

Cahill, E. M. et al. Metallic microneedles with interconnected porosity: a scalable platform for biosensing and drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 80, 401–411 (2018).

Zeng, Q. et al. Porous colorimetric microneedles for minimally invasive rapid glucose sampling and sensing in skin interstitial fluid. Biosensors 13, 537 (2023).

Zhu, D., Liu, B. & Wei, G. Two-dimensional material-based colorimetric biosensors: a review. Biosensors 11, 259 (2021).

Li, X. & Liu, X. Fabrication of three-dimensional microfluidic channels in a single layer of cellulose paper. Microfluid Nanofluidics 16, 819–827 (2014).

Evans, E., Gabriel, E. F. M., Coltro, W. K. T. & Garcia, C. D. Rational selection of substrates to improve color intensity and uniformity on microfluidic paper-based analytical devices. Analyst 139, 2127–2132 (2014).

Miyazaki, C. M. et al. Self-assembly thin films for sensing. Mater. Chem. Sens. Chapter 7, 141–164 (2017).

Cha, R., Wang, D., He, Z. & Ni, Y. Development of cellulose paper testing strips for quick measurement of glucose using chromogen agent. Carbohydr. Polym. 88, 1414–1419 (2012).

Qin, B., Park, J., Jing, H., Bao, L., & Kim, B. Porosity control of polylactic acid porous microneedles using microfluidic technology. IEEE CPMT Symposium Japan (ICSJ). IEEE 127–130 (2022).

Kong, T. et al. Droplet based microfluidic fabrication of designer microparticles for encapsulation applications. Biomicrofluidics 6, 34104 (2012).

Tan, S. H. et al. Design of hydrogel-based scaffolds for in vitro three-dimensional human skin model reconstruction. Acta Biomater. 153, 13–37 (2022).

Ed-Daoui, A. & Snabre, P. Poroviscoelasticity and compression-softening of agarose hydrogels. Rheol. Acta 60, 327–351 (2021).

Fogh-Andersen, N., Altura, B. M., Altura, B. T. & Siggaard-Andersen, O. Composition of interstitial fluid. Clin. Chem. 41, 1522–1525 (1995).

Bollella, P., Sharma, S., Cass, A. E. G. & Antiochia, R. Microneedle-based biosensor for minimally-invasive lactate detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 123, 152–159 (2019).

Wu, L., Park, J., Kamaki, Y. & Kim, B. Optimization of the fused deposition modeling-based fabrication process for polylactic acid microneedles. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 7, 58 (2021).

Summerfield, A., Meurens, F. & Ricklin, M. E. The immunology of the porcine skin and its value as a model for human skin. Mol. Immunol. 66, 14–21 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded and supported by Japan Science and Technology Agency SPRING (Grant number: JPMJSP2108), Japan, and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Core-to-Core Program A (Grant number: JSPSCCA20190006), also partially supported by 2025 Hyper-Convergence Research Support Program (0681-20250036) at Seoul National University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and validation, B.Q., J.P., and B.K.; software, B.Q.; investigation, B.Q., and J.P.; resources, B.K.; data curation, B.Q., J.P., and B.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Q.; writing—review and editing, B.Q., J.P., S.J. K., and B.K.; visualization, B.Q.; supervision, J.P., and B.K.; project administration, B.K.; funding acquisition, B.K. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, B., Park, J., Kim, S.J. et al. Controllable-pore porous microneedles for high-speed extraction and biomarker detection of interstitial fluid. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 240 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01103-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01103-1