Abstract

Flexible photodetectors with wavelength-selective response are essential for next-generation wearable and bio-integrated optoelectronics. However, conventional devices typically rely on external filters or complex structures, limiting the flexibility, integration, and broadband applications. Here, we present a gate-tunable flexible photodetector based on asymmetric van der Waals heterostructures composed of graphene, Molybdenum disulfide and single-walled carbon nanotubes. The asymmetric design induces a built-in electric field, effectively suppressing dark current and enabling dynamic modulation of spectral responsivity via gate voltage. As a result, the device achieves switchable photoresponse peaks at 450 nm and 635 nm, demonstrating a high responsivity of up to 40.3 A/W and a specific detectivity of 1.3 × 1011 Jones. Furthermore, the device maintains robust performance under mechanical deformation and gate voltages. This work offers a scalable approach to realize intrinsically wavelength-selective, high-performance photodetectors on flexible substrates, providing new opportunities for integrated, broadband, and flexible optoelectronic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photodetectors, as the core components of optical detection systems1,2, are critical to a wide range of emerging flexible applications, including wearable health monitoring3,4, curved multispectral imaging5,6, and flexible optical communications7,8. In these scenarios, photodetectors are expected not only to provide mechanical stability9,10, but also to offer broad spectral response and selective detection of specific wavelength bands11,12,13. However, conventional rigid photodetectors—typically based on Si or InGaAs—struggle to accommodate mechanical deformation due to their brittle substrates and interfacial stress concentration14,15. Meanwhile, most flexible broadband photodetectors rely on external optical filters or diffraction gratings for wavelength selectivity16,17,18, which undermines device compactness, flexibility, and integration due to added bulk, optical loss, and fabrication complexity19,20.

To overcome these limitations, various strategies have been explored. The introduction of flexible optical filters21, such as plasma metasurfaces22, offers some spectral selectivity, but these structures often require complex fabrication processes and can introduce additional optical losses, limiting their practical utility. Quantum dot photodetectors exploit resonant cavity enhancement for wavelength tuning23,24, but the approach demands precise nanostructure control, and the growth of quantum dots on flexible substrates remains challenging25,26. Perovskite-based photodetectors can achieve spectral tunability via voltage-induced strain and bandgap modulation27,28,29, yet the intrinsic toxicity of perovskite materials restricts their application in wearable devices30,31. While much recent work has aimed to broaden the detection range and improve response speed, the potential for band tunability in heterojunction devices remains underexploited, particularly for achieving in-situ spectral differentiation.

In this context, two-dimensional (2D) materials—such as Molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂)32, single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT)33, and graphene (Gr)34—have emerged as promising candidates for next-generation broadband photodetectors, owing to their atomic thickness35,36, strong light-matter interaction37,38,39, and tunable electronic band structures40. Heterojunctions formed by stacking different 2D materials via van der Waals forces exhibit unique band alignments41,42, governed by differences in work function and interfacial charge transfer43. Band engineering enables one to overcome the intrinsic limitations of single materials44, while the Fermi level and carrier injection pathways can be dynamically modulated by applying a gate voltage, offering new routes for wavelength-selective photodetection45,46,47.

Here, we report a gate-tunable flexible photodetector based on an asymmetric van der Waals heterostructure comprising Gr, MoS2, and SWCNT. In our device, MoS2 serves as the channel material, while asymmetric Gr–MoS2 and SWCNT–MoS2 pn junctions at the two ends of MoS2 establish opposing built-in electric fields. By tuning the relative Fermi level position of MoS2 via gate voltage, the injection pathways of photogenerated carriers can be modulated, enabling intrinsic spectral differentiation. The device exhibits switchable photoresponse peaks at 450 nm and 635 nm, with a maximum responsivity of 40.3 A/W and a specific detectivity up to 1.3 × 10¹¹ Jones. Importantly, the asymmetric heterojunction design effectively suppresses dark current at low bias, greatly enhancing weak-light detection capability. Moreover, the photodetector demonstrates outstanding operational stability under repeated mechanical deformation and various gate voltages. This work presents a new design paradigm for fabricating wavelength-selective, high-performance photodetectors on flexible substrates, opening new avenues for future wearable and integrated optoelectronic systems.

Results and discussion

Design and mechanism of gate-tunable flexible photodetector with wavelength-selective response

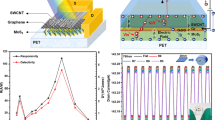

To realize gate-tunable spectral selectivity in the flexible substrate, we designed a photodetector composed of asymmetric Gr/MoS₂/SWCNT heterostructures on a flexible Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate (Fig. 1a), a bottom gate Au/Cr electrode is prepared to regulate the Fermi level (Ef) of MoS248. There is a silicon dioxide (SiO2) dielectric layer between the bottom gate electrode and MoS2 film to prevent current leakage and form a capacitor structure, so that the Vg can effectively regulate the channel carrier concentration. MoS2 film is used as the channel material of the device, and Gr-MoS2 pn junction and SWCNT-MoS2 pn junction are constructed at both ends of it, which form two asymmetric built-in electric fields for dark current suppression and Vg modulation for spectral differentiation. Finally, source and drain Au/Cr electrodes are prepared at both ends of the Gr and SWCNT films to form a complete device.

a Schematic of the 3D structure of the flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT. b Schematic of the working principle of the flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT. c Photograph of the flexible photodetector based on PET substrate. d SEM image of the flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT. e Comparison of Raman spectra of the flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT and the original MoS2 film. f Comparison enlarged diagram of MoS2 peak

Figure 1b shows the built-in electric field distribution of the device under equilibrium state, in which the MoS2 is used as the channel material to form two asymmetric pn junctions of Gr/MoS2 and SWCNT/MoS2. Under the action of the two asymmetric heterojunctions, a potential difference is formed inside the MoS2 channel to hinder the generation of dark current, and the Ef of MoS2 is adjusted by the Vg to achieve spectrum differentiation. Figure 1c shows the flexible photodetector based on the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT asymmetric heterostructure after fabrication, demonstrating the good flexibility of the device. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) shows the surface morphology of the device (Fig. 1d), where SWCNT and Gr are in contact with MoS2 on the left and right sides, respectively. The contact between them can be clearly seen through the enlarged image, which forms the basic structure of the device. In the device, SWCNT and Gr films are used both as functional materials to form heterojunctions with MoS2 and as electrodes to transport carriers. Figure S1 in Supplementary Information shows clear edges of the MoS2 film by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), indicating that the MoS2 film can be prepared by spin coating of their dispersions. Fig. S2 in Supplementary Information shows the element images analyzed using Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS), including the SEM image of the contact between SWCNT and MoS2, the image of the C element distribution, the image of the S element distribution, and the image of the Mo element distribution. The EDS image of the contact between Gr and MoS2 is shown in the Supplementary Information (Fig. S3). The clear boundaries of the elements can be seen from Figs. S2 and S3, indicating the excellent interface preparation of the device.

In order to further demonstrate the combination of the three materials, the Raman spectra of the original MoS2 material and the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT device are shown in Fig. 1e, where it can be seen that for the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT device, the defect mode peak (D) of Gr and SWCNT appears near 1344 cm-1, which represents the ring breathing vibration mode of the sp3 hybridized carbon atom ring. The intensity of the ring-breathing vibration mode corresponds to the degree of defects and disorder in the carbon lattice, and the very small peak represents the small structural defects of Gr and SWCNT. The vibration mode peak (G) appears near 1577 cm-1, which represents the in-plane vibration mode caused by sp2 hybridized carbon atoms. The intensity of this peak is indicative of the degree of completeness of Gr and SWCNT, with a very large peak representing their structural integrity. The frequency-doubling mode peak (2D) appears at 2685 cm-1, which represents the vibration mode of two photonic lattices. The intensity ratio of this peak to the G peak is employed as a metric to determine the number of layers of Gr (I2D/IG), which is larger than the 2D peak due to the superposition of Gr and SWCNT. The changes in the Raman peaks of MoS2 are compared in the enlarged image of Fig. 1f. The in-plane vibration characteristic peak (E12g) is sensitive to the carrier concentration of the material, and its peak shifts from 384 cm-1 to around 377 cm-1, which indicates that the hole carriers of Gr and SWCNT diffuse into MoS2; the electron carriers of MoS2 diffuse into Gr and SWCNT, which makes the carrier concentration of MoS2 changed and the E12g peak shifted. The out-of-plane vibration characteristic peak (A1g) is related to the number of layers of the material, and its peak is basically unchanged, which indicates that the combination of MoS2 with Gr and SWCNT has no effect on the change of its own number of layers.

Dark current suppression by asymmetric heterojunction

We investigated the origin of low dark current in the device and found that the asymmetric heterojunctions generate internal electric fields that effectively suppress carrier leakage under low bias. We tested the light and dark current of the device under the Vg of 0 V, as shown in Fig. 2a. It can be seen from the figure that there is a smooth region of low dark current between −1 V and 1 V in the device under dark conditions; when illuminated, a large photocurrent is generated, and there is no smooth region of low current. In order to further illustrate the working principle of the device, the band theory is used to analyze the dark current phenomenon of the photodetector49, and the band diagram of the device is shown in Fig. 2b. The work function of SWCNT (approximately 4.9 eV) is higher than that of MoS2 (approximately 4.3 eV) and slightly higher than that of Gr (approximately 4.6 eV)50,51,52. This creates favorable conditions for charge transfer, When Gr contacts MoS2, due to their different carrier concentrations, according to the diffusion effect, the high-concentration electron carriers in MoS2 flow to Gr, and the high-concentration hole carriers in Gr flow to MoS2, resulting in the formation of a built-in at the interface, and the direction of the electric field is from Gr to MoS2. Under the action of the built-in electric field, the carriers drift in opposite directions. The holes in MoS2 drift toward the Gr, and the electrons in the Gr drift toward MoS2, until the carrier diffusion and drift motion reach equilibrium. When the SWCNT contacts MoS2, the same principle of the built-in electric field generated by the Gr-MoS2 pn junction is used, and the direction of the built-in electric field is from the SWCNT to the MoS2. Because the built-in electric fields are different between the two sides, the built-in electric field of SWCNT/MoS2 is significantly greater than that of Gr/MoS253,54, which makes more electrons in MoS2 are diffused into SWCNT, and the electron carriers in MoS2 will produce a diffusion motion from the Gr end to the SWCNT end, so that the electric field will be formed between the channel of MoS2.

a I–V curves of the flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT under light and dark conditions. b Schematic diagram of the band of the flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT under dark conditions. c Schematic diagram of the band of the flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT under illumination conditions. d Photoresponsivity and specific detectivity of the flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT

Under illumination, the band diagram of the device is shown in Fig. 2c, the photogenerated carriers at both ends of the heterojunction move in opposite directions under the action of the built-in electric field of the pn junction. The photogenerated electrons generated by the SWCNT into the MoS2; the photogenerated holes generated by the MoS2 into the SWCNT. This makes the potential at the SWCNT end to increase and the potential at the MoS2 end to decrease, offsetting the built-in electric field generated by the pn junction. The heterojunction formed by Gr and MoS2 has the same principle, which eliminates the electric field generated by the asymmetric heterojunction, and the photocurrent changes linearly at this time. We also prepared a SWCNT/MoS2/SWCNT symmetric flexible photodetector and conducted the photoelectric test under the same conditions. The test results are shown in Supplementary Information (Fig. S4). The absence of this phenomenon in the light-dark current diagram of the symmetric device verifies the effect of the asymmetric heterojunctions in blocking the dark current. According to the above principle, the device can suppress the generation of dark current and improve the ability to detect weak signals, which is shown by the responsivity (R) and specific detectivity (D*) in Fig. 2d. Here, the responsivity R is defined as:

where Ip is the photocurrent, P is the optical power density of the incident laser, and A is the effective photosensitive area of the device. The calculation formula for the photocurrent Ip is:

where IL is the current of the device under light conditions, and ID is the current of the device under dark conditions. The specific detectivity (D*) is defined as:

where q is the electron charge, and here q is taken as 1.6 × 10−19. At the Vd of 1 V, the photocurrent Ip of the SWCNT/MoS2/SWCNT flexible photodetector is 0.550 μA, the R is 3.4 A/W, the ID is 0.917 μA, and the D* is 2.8 × 1010 Jones. The R and D* of the SWCNT /MoS2/SWCNT flexible photodetector are shown in Supplementary Information (Fig. S5); the Ip of the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT flexible photodetector is 0.988 μA, the R is 6.1 A/W, the ID is 0.057 μA, and the D* is 1.2 × 1011 Jones. Compared with the symmetric device, the D* of the asymmetric device is improved by an order of magnitude, which proves the improvement of the device’s weak signal detection capability.

From the band structure and built-in electric field perspectives, the difference arises from the internal potential distribution within the MoS2 channel. In symmetric devices (SWCNT/MoS2/SWCNT), the two pn junctions formed at both ends of MoS2 have identical built-in electric field directions but equal magnitudes. As a result, the electric fields cancel each other inside the channel, failing to establish a net potential gradient across MoS2. Under dark conditions, this absence of a strong internal barrier allows thermally excited carriers to diffuse freely across the channel, leading to ineffective suppression of dark current. In contrast, the asymmetric Gr/MoS2/SWCNT heterojunctions introduce two pn interfaces with opposite directions but unequal strengths of the built-in electric fields due to different work function differences at the Gr/MoS2 and MoS2/SWCNT interfaces. This imbalance generates a nonuniform potential gradient across the MoS2 channel, as confirmed by our experimental results in Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5, which significantly blocks the transport of thermally excited carriers and thereby reduces the dark current by nearly one order of magnitude compared to symmetric devices.

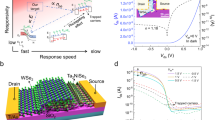

Effects of gate modulation

We tested the effect of different Vg on the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT flexible photodetector. Figure 3a shows the changes in the ID and IL (450 nm laser irradiation) curves of the device under different Vg conditions (−5V, -2V, -1V, 0 V, 1 V, 2 V, 5 V), and the ID and IL of the devices are both shifted with the Vg. This is because there is significant band bending and charge transfer at the heterojunction interface formed by Gr/MoS2 and MoS2/SWCNT. When the Vg is applied, the conduction band (Ec) and valence band (Ev) positions of MoS2 shift accordingly, changing the situation of carrier injection into the heterojunction, which in turn affects the off-state current point position. The corresponding changes can also be seen in Fig. 3b, c, which demonstrate the change in the R of the device for different Vg in Fig. 3b, and the change in the D* of the device for Vg in Fig. 3c. Figure 3d–f shows the schematic diagram of the Vg modulation change. When Vd > Vg, the gate electric field and the source-drain electric field are in the same direction, and the built-in electric field of the SWCNT/MoS2 heterojunction is enhanced, as shown in Fig. 3d. At this time, the gate electric field will enhance the source-drain electric field, so the ID and IL is positive; when Vd = Vg, the gate electric field and the source-drain electric field cancel each other out, and the carrier transport barrier reaches its peak value, as shown in Fig. 3e. At this time, the device is in a cut-off state, and the current is suppressed to the pA level; when Vd < Vg, the gate electric field and the source-drain electric field are in opposite directions, and the built-in electric field of the Gr/MoS2 heterojunction is enhanced, as shown in Fig. 3f. At this time, the gate electric field will weaken the source-drain electric field, so the ID and IL is negative.

a Light-dark I-V characteristic curve of the device under different gate voltage modulation. b Comparison of device responsivity under different gate voltage modulation. c Comparison of device specific detectivity rate under different gate voltage modulation. d Schematic diagram of internal potential change of device under higher drain voltage. (ESD is the source-drain electric field; Ebi is the built-in electric field; and Eg is the gate electric field). e Schematic diagram of the internal potential change of the device when the drain voltage is equal to the gate voltage. f Schematic diagram of internal potential change of device under higher gate voltage

In order to further prove the effect of Vg modulation on different wavelengths, we the variation of current Vg modulation of the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT flexible photodetector under different wavelength illumination conditions. When the Vg is 0 V, the highest R is generated under 450 nm illumination, followed by the R under 633 nm illumination, and finally the R under 532 nm illumination, as shown in Fig. 4a. When the Vg is 1 V, the R generated under 450 nm illumination is enhanced, which is significantly greater than the R under 633 nm and 532 nm illumination, as shown in Fig. 4b. When the Vg is 1V, the R generated under 633 nm illumination is enhanced, which is significantly greater than the R under 450 nm and 532 nm illumination, as shown in Fig. 4c. It can be seen from these figures that the modulation of the Vg affects the R of the device to illumination of different wavelengths, thereby realizing the function of wavelength band selection. For devices with different Vg and wavelengths conditions the variation of specific detectivity is shown in the Supplementary Information (Figure S6). This change can be seen more clearly in Fig. 4d, which shows the change curves of the R in different bands under the Vd of 5 V. When the Vg is positive, the device achieves an enhancement effect on the illumination in the 450 nm; when the Vg is negative, the device achieves an enhancement effect on the illumination in the 633 nm. By optimizing the effect of the Vg on the device R, the amplification of the signal of a specific wavelength is achieved.

a Variation curves of the responsivity of the device at different wavelengths with the drain voltage under the gate voltage of 0V. b Variation curves of the responsivity of the device at different wavelengths with the drain voltage under the gate voltage of 1V. c Variation curves of the responsivity of the device at different wavelengths with the drain voltage under the gate voltage of -1V. d Modulation of the device's responsivity at different wavelengths by different gate voltages at the drain voltage of 5V. e Schematic diagram of the band of the device under positive gate voltages. f Schematic diagram of the band of the device under negative gate voltages

As cross-validation, the band theory was further employed to analyze the Vg regulated photo response mechanism of the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT flexible photodetector. At zero gate bias, MoS2 behaves as an n-type semiconductor with a relatively high intrinsic Fermi level, forming two heterojunction interfaces with the p-type SWCNT and Gr, respectively. Due to the large difference in work function, the SWCNT/MoS2 interface exhibits stronger pn junction characteristics, accompanied by pronounced band bending; whereas the Gr/MoS2 interface exhibits weaker heterojunction characteristics due to the smaller work function difference. Under illumination, this asymmetry leads to preferential carrier migration: short-wavelength photocarriers tend to migrate toward the Gr side, while long-wavelength photocarriers migrate toward the SWCNT side. When a positive gate voltage is applied, a large number of holes accumulate at the bottom of the MoS₂, increasing the hole concentration in the valence band near the Gr side. This shifts the Fermi level (E’f(Gr-MoS2)) of the Gr/MoS2 junction downward, thereby enhancing the built-in electric field of the Gr/MoS2 pn junction. Under the action of the built-in electric field, more photogenerated electrons transfer from Gr to MoS2, as shown in Fig. 4e. Under short-wavelength illumination, the stronger built-in electric field facilitates efficient photocarrier separation, thereby enhancing photoresponsivity at short wavelengths. Conversely, under a negative gate voltage, a large number of electrons accumulate at the bottom of the MoS2, increasing the hole concentration in the valence band near the SWCNT side. This shifts the Fermi level (E’f(MoS2-SWCNT)) of the MoS2/SWCNT junction downward, thereby enhancing the built-in electric field of the MoS2/SWCNT pn junction. Under the action of the built-in electric field, more photogenerated electrons are transferred from the SWCNT to the MoS2, as shown in Fig. 4f. When exposed to 633 nm light, the enhanced built-in field at the MoS2/SWCNT interface dominates the carrier separation process, selectively improving the device’s responsivity at longer wavelengths. This interfacial charge transfer mechanism explains how the gate voltage dynamically redistributes photogenerated carriers between the two heterojunctions, achieving wavelength-selective photoresponse without the need for external optical filters.

Stability test of the device

In addition, the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT flexible photodetector was further tested in order to verify practical applicability and stability. We used pulsed illumination at 450 nm to test the device at Vd of 2 V and obtained the corresponding pulse current variation curves. The response speed of the photodetector refers to how fast the device responds to light, which is usually measured by the response time, including the rise time (τrise) and the decay time (τdecay). Among them, the τrise is defined as the transition time for the signal intensity to rise from 10% to 90% of the final intensity after the light signal is input to the photodetector, and the τdecay is similar. The shorter the τrise and τdecay, the faster the response speed of the photodetector, thus that the changes in the light signal can be captured quickly. Through the pulse light test, it can be observed that the τrise of the device is 207 ms, and the τdecay is 249 ms, as shown in Fig. 5a. This relatively slow response speed can be attributed to several intrinsic and extrinsic factors. First, the trap states at the MoS2/Gr and MoS2/SWCNT interfaces can capture photogenerated carriers, prolonging the carrier lifetime and delaying recombination dynamics. Second, interface defects arising from solution-based MoS2 deposition and wet transfer processes may induce localized states within the bandgap, further impeding carrier transport. Finally, the inherent carrier mobility limitations of MoS2 compared with materials such as Gr or perovskites may also restrict the transient response. Future optimization strategies include interface passivation, high-quality MoS2 growth, and device architecture engineering to reduce trap states and accelerate carrier transport, thereby improving the response speed.

a Transient rise time and transient decay time of the device. b I–V curves of the device under different gate voltages and wavelengths illumination conditions. c Pulse optical response curves of the device under different gate voltages. d Pulse optical response curves of the device under different bending radii

For the stability test, we conducted pulse response stability tests under different Vg conditions and different bending conditions. The I-V curves of the Gr/MoS2/SWCNT flexible photodetector under different Vg and wavelengths illumination also verify the above theory, and the results are shown in Fig. 5b. Figure 5c shows the pulse current curves of the device under different Vg (−1 V, 0 V, 1 V) modulation, which shows that the Vg has a certain regulatory effect on the light-dark current of the device, but the response speed remains basically unchanged. Figure 5d shows the pulse current curve of the device under artificial bending with different radii (R = 9, 8, 7, 6 mm, R is the bending radius). It can be seen that the light-dark current of the device remains basically unchanged after bending, and the response speed of the device remains basically unchanged. Through the above adaptability and stability tests of the device, the excellent performance of the device is demonstrated, ensuring the practical application of our flexible photodetector in wearable devices.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that asymmetric 2D heterojunctions on a flexible PET substrate enables gate modulation of wavelength-selective photoresponse and effective suppression of dark current under low bias, thereby significantly enhancing the detection capability for weak optical signals. The proposed device exhibits tunable responsivity. When the gate voltage is −1 V, the responsivity is higher at 635 nm, with a value of 40.3 A/W. Under a gate voltage of 1 V, the peak response shifts to 450 nm, with a value of 26.0 A/W. Compared with symmetric SWCNT/MoS₂/SWCNT flexible photodetectors, the asymmetric device demonstrates an order-of-magnitude improvement in specific detectivity, confirming its superior weak-light detection performance. Moreover, the device maintains stable and reliable operation under varying gate voltages and mechanical deformations, as confirmed by pulsed photocurrent measurements at different bending radii. Although this work focuses on gate-tunable wavelength selectivity at 450 nm and 635 nm, the proposed asymmetric heterostructure platform can be extended to broadband and multi-band photodetection by integrating 2D semiconductors with tailored bandgaps and interfacial dipoles. Such spectrally reconfigurable and flexible photodetectors hold great promise for applications in wearable health monitoring, environmental sensing, optical communication, and multispectral imaging.

Methods

Device fabrication

To ensure high device performance and compatibility with large-area scalable manufacturing processes, all materials and processes are implemented to enable low-temperature flexible electronic integration.First, a clean PET substrate was prepared and cleaned with acetone, ethanol and deionized water. Then, EPG 535 photoresist was spin-coated on the PET substrate and exposed using the UV photolithography machine. After development, a gate electrode pattern was obtained. Then, 20 nm Cr and 80 nm Au were deposited on the surface of the photoresist by the electron beam evaporation. Next, the excess photoresist and metal layer on the PET surface were removed by liquid phase stripping to obtain the gate electrode. Then, a layer of metal Al was deposited on the PET surface using UV lithography and electron beam evaporation technology, and a square window of 80 × 80 μm was defined on the metal Al surface; a layer of SiO2 is sputtered on the Al mask layer as the dielectric layer by magnetron sputtering technology, and then the MoS2 dispersion is evenly spin-coated on it and dried to form a MoS2 film; the Al mask is removed by aluminum etching solution to obtain the SiO2 intercalation layer and the upper MoS2 film; then, a Gr film is prepared by chemical vapor deposition and wet-transferred to a PET substrate, completely covering the surface of the SiO2 intercalation layer and the MoS2 film; a layer of photoresist mask with a size of 300 × 60 μm is obtained on the surface of the Gr film by photolithography technology, and then the Gr film not covered by the photoresist mask is removed by oxygen plasma etching technology to obtain a patterned Gr film; then, a layer of Al is deposited on the upper layer of the Gr film by UV lithography and electron beam evaporation technology, and a 300 × 60 μm rectangular window is defined on the surface of the Al. The SWCNT dispersion was evenly spin-coated on the Al mask layer, dried to form a SWCNT film, and the Al mask was removed to obtain a patterned SWCNT film. Finally, 20 nm Cr and 80 nm Au were deposited as source and drain electrodes at both ends of the obtained Gr film and SWCNT film using UV lithography and electron beam evaporation technology to obtain the gate-tunable flexible photodetector based on Gr/MoS2/SWCNT asymmetric heterostructure. The schematic diagram of the device preparation process is shown in Supplementary Information (Fig. S7). The detailed synthesis/processes of Gr, MoS2 and SWCNT film and the wet transfer process of Gr are given in the Supplementary Information.

Materials characterization

SEM images were obtained using a Carl Zeiss Gemini SEM 500 at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV, and EDS elemental analysis images of the devices were obtained using an Oxford EDS System (UltimMax100). AFM images were obtained using INNOVA at a scan line rate of 256. Raman spectra were measured using a confocal Raman microscope (Horiba JOBIN YVON, hr800) with an excitation wavelength of 532 nm and an output power of 100 mW.

Electrical measurements

The electrical measurements were performed on a probe station equipped with a Keysight B1500A Semiconductor analyzer. For optoelectronic testing, power was supplied by an IT6100B high-speed, high-precision, programmable DC power supply, and a solid-state laser generated plane-wave light at wavelengths of 450/532/633 nm. To ensure consistent optical excitation conditions across different wavelengths, the output powers of the three solid-state lasers were carefully calibrated to the same optical power density of 20 mW/cm2 using a commercial Si photodetector (Thorlabs S120VC).

References

Zou, Y. et al. High-temperature flexible WSe2 photodetectors with ultrahigh photoresponsivity. Nat. Commun. 13, 4372 (2022).

Shafique, S. et al. High-performance photodetector using urchin-like hollow spheres of vanadium pentoxide network device. Sens. Actuators A. 296, 38–44 (2019).

Du, B. et al. A water-resistant, ultrathin, conformable organic photodetector for vital sign monitoring. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp2679 (2024).

Yan, T. et al. An all-organic self-powered photodetector with ultraflexible dual-polarity output for biosignal detection. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201303 (2022).

Hong, Y. J., Jeon, B. J., Ki, Y. G. & Kim, S. J. A metasurface color router facilitating RGB-NIR sensing for an image sensor application. Nanophotonics 13, 1407–1415 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. High-order near-field imaging of low-dimensional materials at infrared wavelengths. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 11, 115 (2025).

Bian, L. et al. Self-powered perovskite/Si bipolar response photodetector for visible and near-infrared dual-band imaging and secure optical communication. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2401331 (2025).

Li, Z., Shi, Y., Zou, M., Yu, Y. & Zhang, X. Ultrahigh-power germanium photodetector enabling amplifier-free wireless communication. Laser Photonics Rev. 19, 2401469 (2025).

Zhou, Y. et al. An ultrawide field-of-view pinhole compound eye using hemispherical nanowire array for robot vision. Sci. Rob. 9, eadi8666 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. High-performance broadband flexible photodetector based on Gd3Fe5O12-assisted double van der Waals heterojunctions. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 84 (2023).

Ji, P. et al. High-performance photodetector based on an interface engineering-assisted graphene/silicon Schottky junction. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 9 (2022).

Lan, Z. et al. Near-infrared and visible light dual-mode organic photodetectors. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw8065 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Dispersion-selective band engineering in an artificial kagome superlattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 66302 (2024).

Shafique, S. et al. Improving the performance of V2O5/rGO hybrid nanocomposites for photodetector applications. Sens. Actuators A 332, 113073 (2021).

Bai, P. et al. Broadband and photovoltaic THz/IR response in the GaAs-based ratchet photodetector. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn2031 (2022).

Li, Q., Zheng, J. & Yang, Y. Ultra-small millimeter-wave filter chips based on high-K single-crystal lithium niobate. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 11, 95 (2025).

Choi, I. S. et al. Strain-tunable optical microlens arrays with deformable wrinkles for spatially coordinated image projection on a security substrate. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 98 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. TE-pass/TM-stop on-chip Mach-Zehnder interferometer with high phase sensitivity. Results Phys. 45, 106237 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. High performance, biocompatible dielectric thin-film optical filters integrated with flexible substrates and microscale optoelectronic devices. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 1800146 (2018).

Hui, D. et al. A MEMS grating modulator with a tunable sinusoidal grating for large-scale extendable apertures. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 11, 39 (2025).

Jiang, Y. et al. Flexible film bulk acoustic wave filters toward radiofrequency wireless communication. Small 14, 1703644 (2018).

Oshita, M., Saito, S. & Kan, T. Electromechanically reconfigurable plasmonic photodetector with a distinct shift in resonant wavelength. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 26 (2023).

Hao, Q., Tang, X., Cheng, Y. & Hu, Y. Development of flexible and curved infrared detectors with HgTe colloidal quantum dots. Infrared Phys. Technol. 108, 103344 (2020).

Abbas, K. et al. Graphene photodetectors integrated with silicon and perovskite quantum dots. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 10, 81 (2024).

Luo, Y., Zhang, S., Tang, X. & Chen, M. Resonant cavity-enhanced colloidal quantum-dot dual-band infrared photodetectors. J. Mater. Chem. C. 10, 8218–8225 (2022).

Rizzato, R. et al. Extending the coherence of spin defects in hBN enables advanced qubit control and quantum sensing. Nat. Commun. 14, 5089 (2023).

Guo, L. et al. A single-dot perovskite spectrometer. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200221 (2022).

Ma, Y. et al. Amplified narrowband perovskite photodetectors enabled by independent multiplication layers for anti-interference light detection. Sci. Adv. 11, 1127 (2025).

Abbas, K., Ji, P., Ameer, M. F. & Yang, S. Enhanced photoresponse and stability in graphene/silicon Schottky photodetectors modified with perovskite nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 714, 164485 (2025).

Fang, W. et al. Bioinspired single-shot polarization photodetector based on four-directional grating arrays capped perovskite single-crystal thin film. Sci. Adv. 10, eadr5375 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Interlayer polymerization of 2D chiral perovskite single-crystal films toward high-performance flexible circularly polarized light detection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2306199 (2023).

Qian, C. et al. Probing dark excitons in monolayer MoS 2 by nonlinear two-photon spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 86902 (2024).

Singh, Y. T. et al. N-doped direction-dependent electronic and mechanical properties of single-walled carbon nanotube (SWCNT) from a first-principles density functional theory (DFT) and MD-simulation. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 111, 108111 (2022).

Suo, H., Yang, S., Ji, P. & Wang, Y. Multi-band enhanced graphene photodetector based on localized surface plasmon. Sens. Actuators A 322, 112627 (2021).

Sarwar, H., Ji, P., Shafique, S., Wang, X. & Yang, S. Production of high-quality and large lateral-size black phosphorus nanoparticles/nanosheets by liquid-phase exfoliation. RSC Adv. 13, 1223–1228 (2023).

Ji, P., Qian, C., Finley, J. J. & Yang, S. Thickness insensitive nanocavities for 2D heterostructures using photonic molecules. Nanophotonics 12, 3501–3510 (2023).

Hu, J. et al. All-2D-materials subthreshold-free field-effect transistor with near-ideal switching slope. ACS Nano. 18, 20236–20246 (2024).

Lambada, D. R. et al. Investigation of illumination effects on the electrical properties of Au/GO/p-InP heterojunction with a graphene oxide interlayer. Nanomanuf. Metrol. 3, 269–281 (2020).

Soubelet, P. et al. Strong quantum confinement of 2D excitons in an engineered 1D potential induced by proximal ferroelectric Domain Walls. Nano Lett. 25, 12842–12850 (2025).

Moser, P. et al. Atomically flat dielectric patterns for bandgap engineering and lateral junction formation in MoSe2 monolayers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2418528 (2025).

Qiu, F. et al. Nanoscale spatially resolved terahertz response of a PbS-graphene heterostructure. ACS Nano. 19, 10943–10954 (2025).

Zhao, S. et al. Excitons in mesoscopically reconstructed moiré heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 572–579 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Polarization- and gate-tunable optoelectronic reverse in 2D semimetal/semiconductor photovoltaic heterostructure. Adv. Mater. 36, 2309371 (2024).

Lee, I. et al. Ultrahigh gauge factor in graphene/MoS2 heterojunction field effect transistor with variable Schottky barrier. ACS Nano. 13, 8392–8400 (2019).

Tran, T. U. et al. Gate tunable photoresponse of a two-dimensional p-n junction for high performance broadband photodetector. Appl. Mater. Today 26, 101285 (2022).

Su, B. et al. Gate-tunable photodetectors based on anti-ambipolar transistors composed of black phosphorus/MoS2 nanosheet heterostructures. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 11868–11876 (2023).

Yan, C., Liu, H., Yu, H. & Yang, H. Gate-tunable photodetectors based on MoTe2 /MoS2 heterostructures anti-ambipolar transistors. Nanotechnology 36, 135202 (2025).

Park, J., Park, Y., Yoo, G. & Heo, J. Bias-dependent photoresponsivity of multi-layer MoS2 phototransistors. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 12, 599 (2017).

Hu, Z. et al. Interfacial charge and energy transfer in van der Waals heterojunctions. Infomat 4, e12290 (2022).

Latif, H., Shafique, R., Sattar, A., Shabbir, S. A. & Usman, A. A novel approach of polychiral single walled carbon nanotubes functionalization for heterojunction solar cell. Surf. Interfaces 52, 104899 (2024).

Lattyak, C., Gehrke, K. & Vehse, M. Layer-thickness-dependent work function of MoS2 on metal and metal oxide substrates. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 13929–13935 (2022).

Tanaka, S., Tominari, Y. & Suzuki, H. Work function of layered graphene prepared by chemical vapor deposition in high vacuum. e-J. Surf. Sci. Nanotechnol. 21, 72–77 (2022).

Mustafa, H. et al. First principle study of multilayered graphene/MoS2 heterostructures for photodetectors. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 289, 116205 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. First-principles study of the structural phase transition and optical properties for MoS2 at high pressure. Chem. Phys. Lett. 825, 140579 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China National Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists (No. 52225507); the Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi Province (2024PT-ZCK-40); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. and P.J. contributed equally to this work and revised the manuscript. Z.Z. and S.Y. conceived the idea, designed the experiments and wrote up the manuscript; P.J. built up the experimental system; W.H. and S.Q. conducted the material synthesis; S.Z. helped to fabricate the device; H.D. and W.T. performed the data analysis. The manuscript was revised with the contributions of all authors. It has also been approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Ji, P., Hu, W. et al. Gate-tunable flexible photodetector with wavelength-selective response based on asymmetric 2D heterostructures. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 243 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01109-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01109-9