Abstract

The strategic integration of micro/nano-engineering with controlled optical responses is pivotal for advancing solid tumor therapy. We have constructed a biomimetic nanosystem via the precise encapsulation of a flexible-chain iridium complex (IrC8) within giant plasma membrane vesicles (GPMVs) derived from tumor cells. This micro/nano-scale design leverages the endogenous structure of GPMVs to achieve superior biocompatibility and enhance homologous targeting, resulting in a 4.7% increase in cellular uptake compared to the free complex. The encapsulated IrC8 complex serves as a highly efficient photosensitizer, exhibiting a strong optical response characterized by an aggregation-induced emission enhancement factor (I/I₀) > 10 and a high singlet-oxygen quantum yield (ΦΔ = 0.18). Upon photoactivation, this system generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) with an 18-fold increase in yield, leading to potent phototoxicity with over 90% tumor cell apoptosis. Furthermore, the systematic integration of the vesicular carrier and the photosensitizer initiates a cascade reaction: the photodynamic effect not only directly eradicates tumor cells but also triggers immunogenic cell death (ICD), leading to potent immune activation. This synergistic combination of targeted delivery, photodynamic therapy, and immune stimulation within a single nanosystem demonstrates a remarkable synergistic therapeutic effect against solid tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of integrated nanosystems that combine precise drug delivery with controlled therapeutic activation is a central challenge in oncology. While synthetic nanoparticles have been widely explored, their clinical translation is often hampered by intrinsic limitations in biocompatibility and off-target effects1. In contrast, endogenous carriers, particularly cell-derived vesicles, offer a promising platform for system integration due to their native biological composition and functions2,3.

Among these, Giant Plasma Membrane Vesicles (GPMVs) represent an exceptionally versatile micro/nano-scale vehicle4. Their straightforward isolation from parent cells yields vesicles that preserve the original membrane composition and targeting motifs, while their size (typically several hundred nanometers to microns) is ideal for drug encapsulation and cellular uptake5,6. This makes GPMVs an optimal biomimetic building block for constructing targeted delivery systems.

The therapeutic efficacy of such a system critically depends on its core functional unit7. Iridium complexes have emerged as potent alternatives to traditional photosensitizers. Their rigid three-dimensional configuration facilitates efficient intersystem crossing, a key photophysical process that underpins a strong optical response and enables superior reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation for photodynamic therapy (PDT)8,9.

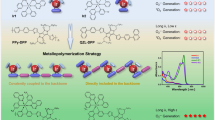

Herein, we report a seamlessly integrated nanosystem designed to synergize these components. We encapsulated a custom-synthesized, flexible-chain cationic iridium complex (IrC8) into GPMVs derived from B16 tumor cells to form G-IrC8. Our design strategy is tripartite: First, the GPMV carrier provides homologous targeting and enhances biocompatibility at the micro/nano-scale10. Second, the IrC8 payload is engineered for an aggressive optical response, featuring aggregation-induced emission (AIE) for localized signal amplification and efficient multi-photon absorption for deep-tissue PDT potential. Third, the inherent mitochondrial targeting of the cationic complex allows for precise subcellular localization, ensuring that the optical response is directed to a critical organelle to maximize therapeutic efficacy. We demonstrate that this integrated system not only achieves targeted photodynamic tumor cell killing but also, through the system-level function of induced immunogenic cell death, initiates a potent adaptive immune response (Scheme 1). This work highlights the power of converging biomimetic nano-design, advanced optical materials, and systematic functional integration into a unified therapeutic platform.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and photodynamic characterization of the biomimetic nanosystem G-IrC8

To construct an effective biomimetic nanosystem for photodynamic therapy (PDT), we synthesized a cationic iridium complex (IrC8) and encapsulated it within giant plasma membrane vesicles (GPMVs) derived from tumor parental cells. The preparation process of G-IrC8 is outlined in Fig. 1a, illustrating sequential steps including treatment of cells with DTT/PFA, isolation of GPMVs via centrifugation, and subsequent IrC8 loading to form the final nanosystem, G-IrC8.

a Schematic representation of the preparation process of G-IrC8, showing cell treatment with DTT and PFA to release GPMVs, followed by centrifugation and IrC8 loading. b Fluorescence microscopy images of G-IrC8 (left), brightfield microscopy images of G-IrC8 (middle), and their merged view (right), showing encapsulation of IrC8 and co-localization within GPMVs. c Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of G-IrC8 (left) and high-magnification TEM image (right), showing the spherical core-shell structure of GPMVs and encapsulation of IrC8. d UV-vis absorption (blue line, left axis) and fluorescence emission (orange line, right axis) spectra of IrC8 in PBS (10 µM). e Fluorescence intensity ratio (I/I0) of IrC8 under different conditions, including interactions with DNA, BSA, liposomes, cardiolipin, and amino acids. f Aggregation-induced emission (AIE) property of IrC8. Statistical significance: **** (p < 0.0001). g Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis showing the size distribution of G-IrC8 (~200 nm) compared to free IrC8. The inset shows photographs of G-IrC8 and IrC8 solutions. h Fluorescence emission spectra of G-IrC8 and free IrC8. i Zeta potential measurements of G-IrC8 and free IrC8

The successful encapsulation of IrC8 into GPMVs was confirmed through microscopic analysis. Confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1b, left panel) revealed strong yellow fluorescence within GPMVs, corresponding to encapsulated IrC8. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Fig. 1c) further confirmed the spherical core-shell structure of G-IrC8, with higher magnification clearly showing the uniform encapsulation of IrC8. The merged fluorescence and transmission image (Fig. 1b, right panel) demonstrated spatial co-localization of GPMVs and IrC8, providing direct evidence for successful nanosystem construction.

The synthesis method is outlined in the supporting materials, with detailed explanations of each step involved. (Figs. S1-S2). The fundamental chemical properties of the IrC8 provided a solid foundation for the successful encapsulation process. As shown in Fig. 1d and h, the consistent fluorescence signal upon excitation suggests that the probe has not been degraded or released prematurely, thereby supporting the successful and efficient encapsulation into GPMVs. Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity of IrC8 was significantly enhanced upon interaction with biomimetic components such as liposomes, as demonstrated in Fig. 1e, highlighting its potential for selective targeting in membrane environments. Meanwhile, IrC8 demonstrates stability across a range of pH environments. (Fig. S3)

The aggregation-induced emission (AIE) properties of IrC8 were also assessed, as this is a critical feature for both its photodynamic performance and its potential in vivo applications11. As shown in Fig. 1f, the fluorescence intensity of IrC8 increased significantly in the aggregated state compared to its dispersed state, with statistical analysis confirming this enhancement (p < 0.00001). This AIE property ensures high fluorescence stability and sensitivity in complex biological environments. Importantly, this feature is advantageous for localized accumulation and enhanced photodynamic activity, maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis was employed to characterize the nanosystem’s hydrodynamic properties. As shown in Fig. 1g, compared to the free IrC8, encapsulating the IrC8 into GPMVs substantially altered its size distribution and stability. The encapsulation process led to a marked shift in the particle size distribution, with the resulting GPMVs showing a more uniform size range, G-IrC8 exhibited an average size of approximately 200 nm with a narrow distribution, making it suitable for drug delivery applications. Additionally, the stability of IrC8 was significantly enhanced within the GPMVs, as evidenced by its prolonged retention and reduced susceptibility to environmental degradation, as highlighted in the inset image. Zeta potential analysis revealed that the surface of G-IrC8 exhibited a negative charge close to −20 mV (Fig. 1i), ensuring colloidal stability in physiological environments, which is crucial for their potential biomedical or nanomaterial applications12. Surprisingly, GPMVs derived from B16 cells themselves were found to effectively promote cell death in B16 cells, while having no significant effect on the non-homologous Bend3 cells (Fig. S4). This selective toxicity suggests that the GPMVs may interact specifically with B16 cell receptors or pathways involved in cell death, while remaining inert or ineffective in Bend3 cells13. These findings highlight the potential for targeted therapeutic applications, where GPMVs could selectively induce cell death in specific cell types.

Collectively, these results establish that G-IrC8 not only retains the structural and fundamental chemical properties of IrC8 but also achieves compatibility with GPMVs, making it a promising candidate for therapeutic applications, including peritumoral administration, due to its enhanced stability, fluorescence intensity, and localized activation. Having established the successful construction and basic photophysical properties of the G-IrC8 nanosystem, we next sought to verify that its design conferred the intended homologous targeting behavior at the cellular level.

Verification of cell adhesion molecules and homologous targeting of cells

Homotypic aggregation of tumor cells relies on cell-surface interactions mediated by tumor-specific adhesion molecules, binding proteins, and membrane recognition molecules14. To evaluate the successful functionalization of G-IrC8 with tumor-specific adhesion molecules, we examined key proteins such as Na/K-ATPase and CD146. Na/K-ATPase, a cell membrane-specific protein, and CD146, a self-marker for B16 cells, are critical for tumor-specific adhesion and recognition15,16. Western blotting and Coomassie blue staining confirmed that G-IrC8 retained membrane-associated proteins from B16 cells, including Na/K-ATPase and CD146 (Fig. S5).

The homologous targeting ability of G-IrC8 was further assessed by fluorescence imaging and flow cytometry. B16 cells incubated with G-IrC8 exhibited significantly higher fluorescence intensity compared to cells treated with free IrC8 at the same concentration, as shown in Fig. S6. This difference became more pronounced with prolonged incubation, consistent with flow cytometry results. After encapsulation into GPMVs, the uptake rate of IrC8 by B16 cells increased by 4.7% within a short incubation period, confirming the enhanced homologous targeting capability of G-IrC8 (Fig. S7).

Exploration of photodynamic induced apoptosis in vitro

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), as a product of oxidative stress, play a crucial role in tumor cell proliferation and apoptosis. To evaluate the ROS generation capacity of G-IrC8, we first measured fluorescence intensity changes of the ROS indicator DCFH in PBS. Upon 365 nm laser irradiation for 1 min, the fluorescence intensity at 520 nm increased by 17-fold in the presence of G-IrC8 compared to the laser-only group (Fig. 2a). Further analysis revealed that the primary ROS generated by G-IrC8 was singlet oxygen, with a higher singlet oxygen conversion efficiency (Φ = 0.18) compared to the commercial photosensitizer [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (Fig. 2b).

a Fluorescence intensity ratio (I/I0) of DCFH for ROS generation by G-IrC8 compared to the Blank group. b Singlet oxygen quantum yield (Φ) of G-IrC8 and [Ru(bpy)3]2+, showing enhanced ROS generation efficiency. c, d Cell viability of B16 cells after different treatments (Blank, Probe, Laser, Probe+Laser) measured using MTT assay. e Confocal imaging of intracellular ROS generation (Green: DCFH fluorescence) and live/dead cell staining (Green: Calcein AM; Red: PI) after various treatments. f Flow cytometry analysis of cell death patterns, with Q2 (late apoptosis) and Q3 (early apoptosis)). g 3D tumor spheroid models treated with G-IrC8, showing significant cell death (Red: PI) after laser irradiation

To verify intracellular photodynamic effects, B16 cells were incubated with G-IrC8 and exposed to 365 nm laser irradiation. As shown in Fig. 2c, rapid cell death was observed within 1 hour only in the G-IrC8 + Laser group, which was consistent with the extracellular results. After 24 h, a significant amount of cell death was observed in the G-IrC8 group (Fig. 2d), suggesting that G-IrC8 not only exhibits an excellent photodynamic effect but also effectively induces tumor cell apoptosis, thereby providing a promising avenue for the integration of photodynamic therapy with chemotherapy (Fig. 2d). ROS imaging further confirmed these findings, as significant ROS fluorescence was detected exclusively in the G-IrC8 + Laser group after just 1 min of irradiation (Fig. 2e).

The efficacy of photodynamic therapy (PDT) was further explored using Calcein AM/PI staining. B16 cells treated with G-IrC8 exhibited extensive cell death (PI, red) following laser irradiation, as shown in Fig. 2e. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that most of the cells showed late apoptosis (Q2), and the apoptosis rate was more than 90% in the G-IrC8 + Laser group (Fig. 2f). Finally, the photodynamic effects of G-IrC8 were validated in 3D tumor spheroid models. Confocal imaging showed significant disruption of spheroids and extensive cell death in the G-IrC8 + Laser group (Fig. 2g), highlighting the ability of G-IrC8 to induce apoptosis and achieve effective tumor suppression.

Mechanisms of subcellular targeting and cellular death

Targeted delivery of drugs can improve bioavailability, bypass drug resistance, and enhance therapeutic efficacy. The subcellular distribution of G-IrC8 in B16 cells was analyzed by confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3a, G-IrC8 exhibited strong co-localization with MitoTracker Deep Red, a mitochondria-specific dye, in both live and fixed cells, with Pearson’s correlation coefficients (Rr) of 0.92 and 0.82, respectively. These results confirm that G-IrC8 preferentially accumulates in mitochondria, likely through an embedding mechanism. Moreover, at concentrations as low as 1 μM, clear mitochondrial targeting was achieved, with the compound demonstrating significantly better photostability compared to the mitochondrial dye MTDR. This enhanced stability allows for more reliable and prolonged imaging, facilitating accurate tracking of mitochondrial changes over time (Figs. S8-S9).

a Confocal microscopy showing G-IrC8 co-localized with mitochondria-specific dye MitoTracker Deep Red in fixed and live cells. Green: G-IrC8; Red: MitoTracker Deep Red; Rr: Pearson’s correlation coefficient. b Time-lapse imaging of mitochondrial morphology changes after G-IrC8 pretreatment and laser activation. G-IrC8 fluorescence highlights the transition from tubular to fragmented mitochondrial structures over 210 seconds. c, d Quantification of mitochondrial membrane potential changes in different treatment groups, measured using MitoRed. Statistical analysis shows a significant reduction in membrane potential in the G-IrC8 + Laser group compared to other groups (*p < 0.05). e, f DNA Comet assay showing ROS-induced nuclear DNA tailing. Quantification of tail DNA percentage indicates significantly higher DNA damage in the G-IrC8 + Laser group compared to the Control, G-IrC8, and Laser groups (**p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001). g Western blot analysis of Bax, Bcl2, Caspase 3, and cleaved-Caspase 3 in different groups. Heatmap on the right shows Bax/Bcl2 and cleaved-Caspase 3/Caspase 3 ratios, with significant increases in the G-IrC8 + Laser group compared to the Control group (p < 0.05). h Schematic illustrating the proposed mechanism of G-IrC8-induced apoptosis via mitochondrial targeting, fragmentation, ROS generation, and DNA damage

To further understand the effects of G-IrC8 on mitochondrial morphology, time-lapse imaging was performed using G-IrC8 as a fluorescent marker. As shown in Fig. 3b, G-IrC8 fluorescence revealed a time-dependent increase in mitochondrial fragmentation upon laser activation. Over 210 s, mitochondria transitioned from elongated, tubular structures to fragmented, punctate forms, indicating PDT-induced mitochondrial damage.

In addition to mitochondrial fragmentation, the effect of G-IrC8 on mitochondrial membrane potential was analyzed using MitoRed, a dye sensitive to mitochondrial membrane potential. Confocal imaging revealed that the G-IrC8 + Laser group exhibited a significant reduction in MitoRed fluorescence intensity compared to other groups (Fig. 3c). Quantitative analysis confirmed that mitochondrial membrane potential was significantly disrupted in the G-IrC8 + Laser group, suggesting that G-IrC8-induced mitochondrial dysfunction plays a key role in apoptosis initiation.

Beyond mitochondrial damage, ROS production was accompanied by significant DNA damage and assessed by DNA Comet assays. As shown in Fig. 3d, the G-IrC8 + Laser group exhibited extensive DNA tailing, indicative of severe ROS-induced DNA strand breaks. Quantification of tail DNA percentage revealed a significant increase in the G-IrC8 + Laser group compared to all other groups (p < 0.01). This cascade of mitochondrial damage and nuclear DNA disruption highlights the dual-targeting photodynamic effects of G-IrC8.

At the molecular level, the apoptotic mechanism induced by G-IrC8 was further explored using Western blotting. As shown in Figs. 3e and S10, key apoptosis-related proteins, including Bax, Bcl2, Caspase 3, and cleaved-Caspase 3, were analyzed. The Bax/Bcl2 ratio, an indicator of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis, was markedly increased in the G-IrC8 + Laser group, reaching a value of 3.2 compared to 1.2 in the Control group. Similarly, the cleaved-Caspase 3/Caspase 3 ratio, a hallmark of caspase-dependent apoptosis, increased to 2.8 in the G-IrC8 + Laser group compared to 0.9 in the Control group. Meanwhile, no significant changes were observed in either the imaging co-localization coefficient for mitochondria and lysosomes or the protein ratio of LC3Ⅱ to LC3Ⅰ (Fig. S11-S12). These findings confirm that G-IrC8 promotes apoptosis via mitochondrial dysfunction and caspase activation, with laser irradiation significantly enhancing these effects17,18.

Finally, the proposed mechanism of G-IrC8-induced apoptosis is summarized in a schematic (Fig. 3f). G-IrC8 first localizes to mitochondria, where it disrupts membrane integrity, induces ROS generation, and promotes mitochondrial fragmentation upon laser activation. This cascade of mitochondrial dysfunction leads to nuclear DNA damage and activates caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways, ultimately inducing cell death. Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of the iridium-based biomimetic nanosystem G-IrC8, highlighting its photodynamic and chemotherapeutic properties. Upon administration, G-IrC8 selectively accumulates in tumor cell mitochondria, where photodynamic therapy (PDT)-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production leads to mitochondrial damage, DNA fragmentation, and immunogenic cell death (ICD). The release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) activates dendritic cells (DCs), which further stimulate CD8+ T cells and macrophages, triggering a robust anti-tumor immune response. The therapeutic cascade combines PDT, chemotherapy, and immune activation to achieve tumor regression in a melanoma model

Photodynamic-triggered immune activation in vitro

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a crucial role in inducing immunogenic cell death (ICD), which is essential for activating adaptive immune responses against tumors19. To investigate whether G-IrC8 induces ICD, we analyzed the translocation of key damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including high mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) and calreticulin (CRT), in B16 cells20.

Confocal microscopy analysis demonstrated that HMGB1 was predominantly localized in the nucleus of untreated B16 cells (Fig. 4a). However, in the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated group, HMGB1 translocated from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and extracellular space (Fig. 4a, right). Quantification of the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic fluorescence ratio confirmed a significant reduction in the G-IrC8 + Laser group compared to other groups (p < 0.05; Fig. 4b), indicating the active release of HMGB1, a hallmark of ICD.

a Confocal imaging of HMGB1 localization in B16 cells after different treatments. Yellow: PI (propidium iodide, nuclear staining); Red: HMGB1. Insets highlight nuclear (left) and cytoplasmic (right) localization of HMGB1. Scale bar: 20 µm. b Quantification of the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic fluorescence ratio of HMGB1. The ratio was significantly reduced in the G-IrC8 + Laser group compared to other groups (*p < 0.05), indicating active HMGB1 release. c Confocal imaging of calreticulin (CRT) redistribution in B16 cells. Blue: DAPI (nuclei); Green: CRT. In the G-IrC8 + Laser group, CRT translocated from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane, as indicated by white arrows. Scale bar: 20 µm. d Quantification of CRT membrane translocation. The proportion of CRT localized on the membrane was significantly increased in the G-IrC8 + Laser group compared to other groups (*p < 0.05). e Flow cytometry analysis of BMDC maturation. Q2 quadrant represents mature DCs (CD80⁺CD86⁺). The proportion of mature DCs was notably increased in the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated group, confirming immune activation. f Quantification of CD80⁺CD86⁺ double-positive BMDCs, showing a significant increase in the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated group (****p < 0.0001), further supporting the role of ICD in promoting antigen-presenting cell function

Similarly, CRT exposure was examined by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4c). In untreated cells, CRT fluorescence was primarily localized in the cytoplasm. Following G-IrC8 + Laser treatment, CRT redistributed to the cell membrane, as indicated by white arrows, suggesting its extracellular exposure (Fig. 4c, right). This CRT translocation is another critical marker of ICD, as membrane-bound CRT acts as an “eat me” signal, enhancing antigen presentation by dendritic cells (DCs). Quantitative analysis (Fig. 4d) confirmed a significant increase in membrane-bound CRT in the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated group compared to other groups (p < 0.05).

To evaluate the immunostimulatory effects of DAMP release, the maturation of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) was assessed via flow cytometry (Fig. 4e). Representative flow cytometry plots highlight the proportion of mature DCs (CD80⁺CD86⁺), which was significantly increased in the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated group compared to control groups. Quantification of CD80⁺CD86⁺ DCs (Fig. 4f) demonstrated a substantial increase in the proportion of fully mature antigen-presenting cells following treatment (****p < 0.0001), reinforcing the conclusion that photodynamic activation of G-IrC8 effectively triggers ICD and promotes adaptive immune activation. These results demonstrate that the optical response of G-IrC8, upon precise photoactivation, is functionally translated into a potent immunogenic signal. The induction of ICD is not merely a bystander effect but a direct and intended system-level output, which programs the tumor microenvironment for subsequent immune recognition.

Secondary activation of adaptive and innate immunity: CD8+ T cell activation and immune modulation

To investigate the immunomodulatory effects of G-IrC8 combined with photodynamic therapy (PDT), CD8⁺ T cell activation was assessed using flow cytometry after different treatment conditions (Fig. 5a-c). Murine splenocytes were obtained by mechanical dissociation, and leukocytes were further isolated using Ficoll gradient centrifugation21,22. The isolated cells were plated in six-well plates and cultured in complete medium, supernatant from untreated B16 cells (B16 supernatant), GPMVs from B16 cells, or supernatant from G-IrC8 + Laser-treated B16 cells. Cells were incubated for 3 and 7 days, followed by flow cytometry analysis of CD8⁺ T cell populations.

a, b Flow cytometry analysis of CD8⁺ T cells from murine splenocytes after 3 and 7 days of incubation with different B16-derived supernatants (untreated B16 supernatant, GPMVs from B16, and G-IrC8 + Laser-treated supernatant). Day 3: CD8⁺ T cell levels remained low in all groups, with a decrease in the G-IrC8 + Laser group. Day 7: CD8⁺ T cell levels increased in the G-IrC8 + Laser group, while other groups showed decreased change. c Flow cytometry analysis of macrophage polarization. CD86 (M1 marker) levels increased. d Immunofluorescence staining of tumor sections. HMGB1 and CRT staining was performed to assess DAMPs release. Ki67 and CD4⁺/CD8⁺ T cell staining were used to evaluate tumor proliferation and immune cell infiltration. e Histological analysis of tumor tissues. H&E staining was used to observe tissue morphology, and TUNEL staining was used to detect apoptotic cells. f Flow cytometry analysis of immune cell populations in tumors and blood. CD80⁺CD86⁺ dendritic cells, CD8⁺ T cells, and M1 macrophages were quantified across different treatment groups

At day 3, flow cytometry analysis (Figs. 5a and S13) revealed that CD8⁺ T cell activation was not significantly induced in any treatment group. Surprisingly, the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated supernatant group showed a transient suppression of CD8⁺ T cell activation, suggesting a possible early-phase inhibitory effect. This immunosuppressive effect may be attributed to the presence of high levels of inflammatory cytokines and stress signals in the supernatant, potentially leading to immune cell apoptosis or functional exhaustion.

At day 7, the CD8⁺ T cell population in the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated group exhibited a significant increase, surpassing all other groups, including the control (Figs. 5b and S14). In contrast, CD8⁺ T cell activation in the other treatment groups either remained suppressed or showed signs of immune exhaustion. This delayed yet robust activation of CD8⁺ T cells suggests that G-IrC8-induced ICD effectively primes an adaptive immune response, leading to a sustained anti-tumor immune activation.

To further assess the impact on innate immunity, macrophage activation and polarization were analyzed via flow cytometry (Fig. 5c). CD86, a marker of M1 pro-inflammatory macrophages, was significantly upregulated in the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated group, suggesting enhanced macrophage activation and antigen-presenting capability. These findings suggest that G-IrC8 treatment not only activates macrophages but also reprograms the tumor microenvironment toward an anti-tumor immune response.

Tumor Microenvironment Remodeling in vivo

To further validate the immunomodulatory effects in vivo, a B16 melanoma-bearing C57BL/6 mouse model was established, and immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence analyses were performed on tumor tissues (Fig. 5d, e). Based on the excellent biocompatibility of G-IrC8 (Fig. S15), mice were treated with either PBS (control) or G-IrC8 + PDT for three cycles, followed by tumor collection and staining for various immune markers.

HMGB1 and CRT immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 5d, left panel) revealed a substantial increase in the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated tumors, confirming the induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD) and the release of DAMPs. Ki67 staining (Fig. 5d, right panel) indicated significantly reduced tumor cell proliferation in the treatment group, consistent with tumor regression. CD86⁺ macrophages and CD4⁺/CD8⁺ T cells (Fig. 5d, bottom left and Fig. S15) were more abundant in treated tumors, highlighting the recruitment and activation of immune effector cells.

To further assess tumor apoptosis and tissue integrity, HE and TUNEL staining were performed (Fig. 5e). The G-IrC8 + Laser-treated tumors exhibited extensive nuclear fragmentation and apoptotic cell death, supporting the efficacy of the combinational treatment.

The data presented in Figs. 4 and 5 collectively show that the localized photoactivation of G-IrC8 triggers a cascade of cellular state changes, from initial DAMPs release to the ultimate activation and recruitment of effector T cells and pro-inflammatory macrophages. This remodeling of the tumor microenvironmental properties from ‘cold’ to ‘hot’ stands as central functional evidence for the success of our integrated nanosystem design.

Systemic immune activation and tumor-specific immunity

To determine whether the localized immune response translated into a systemic effect, immune cell populations in the blood and tumors were analyzed via flow cytometry (Figs. 5f and S17). Tumors from the G-IrC8 + Laser-treated mice showed increased mature dendritic cell (DC) populations, indicating enhanced antigen presentation. Higher frequencies of CD8⁺ T cells suggested sustained tumor-specific immune responses. There was also a shift in macrophage polarization towards M1-like phenotypes, as evidenced by higher CD86 expression, confirming a transition to a pro-inflammatory immune environment. These findings collectively suggest that G-IrC8-based PDT not only induces direct tumor cell death but also triggers an adaptive immune response, leading to immune memory formation.

Conclusion

In summary, we have established a robust biomimetic nanosystem, G-IrC8, through the rational integration of a tumor-homing vesicular carrier and a potent photosensitizer. This micro/nano-scale design effectively merges the biological targeting of GPMVs with the engineered optical response of the iridium complex. The system’s core function relies on the precise mitochondrial localization of IrC8 and its subsequent, potent ROS generation upon photoactivation. This direct photodynamic effect is seamlessly integrated with an indirect immune-activating pathway. The system-level synergy is evidenced by the triggered immunogenic cell death, which reprograms the tumor microenvironment and activates a sustained anti-tumor immunity. This work underscores a general strategy for cancer therapy: the construction of integrated nanosystems that combine targeted delivery, controlled physical activation (e.g., optics), and multi-faceted therapeutic modalities. The G-IrC8 platform exemplifies how micro/nano-engineering can be harnessed to create sophisticated, multi-functional systems with enhanced therapeutic potential and specificity.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Han, Y., Kim, D. H. & Pack, S. P. Nanomaterials in drug delivery: leveraging artificial intelligence and big data for predictive design, 26 11121 (2025).

Liang, X. et al. Engineering of extracellular vesicles for efficient intracellular delivery of multimodal therapeutics including genome editors. Nat. Commun. 16 4028 (2025).

Du, S. et al. Extracellular vesicles: a rising star for therapeutics and drug delivery, (1477-3155 (Electronic)).

Sezgin, E. Giant plasma membrane vesicles to study plasma membrane structure and dynamics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembranes 1864 183857 (2022).

C. Y. Kao, E. T. Papoutsakis, Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microparticles, their parts, and their targets to enable their biomanufacturing and clinical applications, (1879-0429 (Electronic)).

Yang, C., Xue, Y., Duan, Y., Mao, C. & Wan, M. Extracellular vesicles and their engineering strategies, delivery systems, and biomedical applications. J. Controlled Release 365, 1089–1123 (2024).

Shen, Z. et al. Strategies to improve photodynamic therapy efficacy by relieving the tumor hypoxia environment. NPG Asia Mater. 13 39 (2021).

Zhu, W. et al. An AIE metal iridium complex: photophysical properties and singlet oxygen generation capacity. LID-https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28237914 LID-7914, (1420-3049 (Electronic)).

Szymaszek, P., Tyszka-Czochara, M. & Ortyl, J. Iridium(III) complexes as novel theranostic small molecules for medical diagnostics, precise imaging at a single cell level and targeted anticancer therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 276, 116648 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Recent progress in targeted delivery vectors based on biomimetic nanoparticles. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6 225 (2021).

Cai, X. & Liu, B. Aggregation-induced emission: recent advances in materials and biomedical applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 9868–9886 (2020).

Midekessa, G. et al. Zeta potential of extracellular vesicles: toward understanding the attributes that determine colloidal stability, (2470-1343 (Electronic)).

Buzas, E. I. The roles of extracellular vesicles in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23 236–250 (2023).

Homotypic and heterotypic cell adhesion in metastasis, in: D. Rusciano, D. R. Welch, M. M. Burger (Eds.), Laboratory Techniques in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. (Elsevier, 2000) pp. 9-64.

Duan, H. et al. CD146 bound to LCK promotes T cell receptor signaling and antitumor immune responses in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 131 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. CD146, from a melanoma cell adhesion molecule to a signaling receptor. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5 148 (2020).

Pawlowski, J. & Kraft, A. S. Bax-induced apoptotic cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 529–531 (2000).

Vince, J. E. et al. The mitochondrial apoptotic effectors BAX/BAK activate caspase-3 and -7 to trigger NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-8 driven IL-1β activation, (2211-1247 (Electronic)).

Malla, R. et al. Reactive oxygen species of tumor microenvironment: Harnessing for immunogenic cell death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 1879 189154 (2024).

Chen, F. et al. DAMPs in immunosenescence and cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 106-107, 123–142 (2024).

Bach, M. K. & Brashler, J. R. Isolation of subpopulations of lymphocytic cells by the use of isotonically balanced solutions of ficoll: I. Development of methods and demonstration of the existence of a large but finite number of subpopulations. Exp. Cell Res. 61 387–396 (1970).

Sounbuli, K., Alekseeva, L. A., Markov, O. V. & Mironova, N. L. A comparative study of different protocols for isolation of murine neutrophils from bone marrow and spleen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. (2023).

Acknowledgements

Xiaohui Zhang and Xuelin Tang contributed equally to this work. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171361, 81621003, 21871003) and Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (Grant 2024NSFSC0746 to Y.C.). We thank Mrs.Jingjing Ran for assistance with flow cytometry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiaohui Zhang and Xuelin Tang: Methodology, Data analyses and Writing-original draft. Lin Bai and Rui Zhao: Designed chemical structure. Yaohui Chen and Xiaohe Tian: Funding Acquisition, helped to design the experiments, and corrected the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Sichuan University (Ethics approval No. 20220414004). All procedures followed institutional guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiaohui, Z., Xuelin, T., Bai, L. et al. Iridium complex-loaded biomimetic vesicles enable enhanced photodynamic therapy and immune modulation. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 33 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01146-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01146-4