Abstract

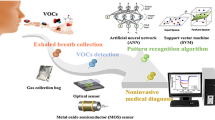

Human exhaled gas is rich in biomarker information that could be used for early diagnosis of disease. With the development of nanotechnology and the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT), AI-assisted nano gas sensor arrays as a non-invasive exhaled gas detection platform brings fascinating technological solutions to the field of breath detection. Herein, we designed a new heterojunction sensing array by anchoring n-GaN nanoparticles on MOF-derived p-MOx porous nanosheets. The gas sensor arrays demonstrated remarkable response speed (10 s), excellent repeatability, and extreme anti-humidity with a lower detection limit of 1 ppb at room temperature. Energy band structure combined with density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to analyze the entire gas sensing process. Furthermore, we developed a new breath detection device and successfully performed clinical patient exhaled gas detection. With the assistance of ensemble learning, the recognition accuracy of lung cancer patients and healthy volunteers can reach 95.8%. This work provides an innovative technology for the construction of heterojunction sensor arrays and exhaled gas detection device, which has a promising application prospect in the field of early disease diagnosis and IoMT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Point-of-care testing (POCT) is an immediate test for rapid on-site sampling, using portable miniaturized equipment and accompanying reagents, which helps to shorten clinical decision-making time1. Studies have confirmed that human exhaled gas is rich in biomarker information that could be used for early diagnosis of disease2,3. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), as the most widespread breath analysis method, has the ability to separate complex gas components. However, the long laboratory analysis process and high cost of GC-MS are not conducive to its rapid clinical diagnostic applications4. Recently, numerous gas sensors and sensor arrays have been developed for exhaled gases detection5,6. Nevertheless, the composition of exhaled gas is particularly complex, the selective identification to trace disease marker gases and humidity anti-interference ability are urgent challenges7. With the development of nanotechnology and the Internet of Medical Things (IOMT), the integration of nanomaterials into intelligent sensor arrays brings fascinating technological solutions to the field of breath detection8. Therefore, AI-assisted nano gas sensor arrays as a non-invasive POCT exhaled gas detection platform is a user-friendly, standardized and affordable method for early exhaled diagnosis and health care evaluation.

Considering the critical role of gas sensors in gas molecular recognition, it is crucial to tailor advanced sensing materials for exhaled gas analysis. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are a class of organic-inorganic hybrid crystal network structures constructed by organic ligands and metal nodes through coordination bonds9. The fascinating properties such as high porosity, large specific surface area, and diverse structures make MOFs as an excellent sensing platform for target gas detection10,11. The diverse structural topology and well-ordered porosity design of MOFs can be achieved by wise selection of inorganic metal nodes/organic ligands and the synthesis conditions, thus facilitating the adsorption and sieving of gas molecules. Nevertheless, limited by the connection of organic ligands, MOFs usually exhibit a high-resistance state, and the structure may collapse under heavy humidity, which is not conducive to the transport of carriers and breath detection 12.

Recently, extensive efforts have been dedicated to improve the gas sensing performance of MOFs. As an effective route, MOFs can be employed as sacrificial templates to derive metal oxides (MOx) with rough and porous structure via simple pyrolyzing, which increases the adsorption site of target gas13. Particularly, MOF-derived p-type MOx, with low humidity dependence and high chemical stability, have great potential for practical exhaled gas detection applications14. However, the pure p-type MOx still face the problems of high temperature operation and low detection limit to be solved15. Further, most MOFs derivatives are cubic, the structures usually collapse and shrink during pyrolysis, resulting in a sharp decrease in the specific surface area and conductive path. A series of innovative strategies such as doping, noble metal modification, and heterostructure construction have been demonstrated to be effective measures in improving detection performance. In these strategies, constructing heterojunction is believed to be much superior due to the large specific surface area, additional electron depletion layer width, and controllable electrical properties16. As a typical wide band gap semiconductor, GaN possesses notable advantages in gas detection field, such as fast carrier transport rate, high chemical stability, corrosion resistance and a weak Fermi-level pinning effect17. Among the diverse shapes of GaN nanostructures, nanoparticles (NPs) have the highest surface area/volume ratio for target gas adsorption18. Therefore, the rational design of MOF-derived MOx and GaN heterostructure is conducive to the synergistic improvement of gas-sensing performance by utilizing the advantages of each component, which is expected to develop smart exhaled gas sensors with high humidity anti-interference and low detection limit under room temperature (RT).

Herein, we developed a new human exhaled gas detection device, which realized clinical exhaled gas detection through an active sampling gas path combined with a 3*2 gas sensing array. The high-performance heterojunction sensing array was successfully prepared by anchoring n-GaN NPs on three two-dimensional (2D) MOF-derived p-MOx porous nanosheets via a simple solvothermal process, and a series of morphological and structural characterizations were executed to demonstrate the successful formation of heterojunction. Energy band structure combined with density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to analyze the entire gas sensing process. Additionally, we successfully constructed classification labels for lung cancer patients and healthy people with an accuracy of 95.8% under the assistance of ensemble learning. This work provides a promising technical route to develop intelligent healthcare equipment for burgeoning POCT non-invasive.

Experimental

Fabrication and characterizations of MOx/GaN gas sensor arrays

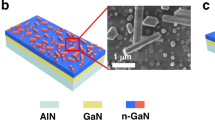

The preparation process of gas sensor arrays as shown in Fig. 1a, a facile solvothermal process and interface self-assembly strategy were employed to synthesize MOF-derived MOx/GaN (MOx=Fe2O3, Co3O4, NiO) p-n heterostructures. To construct hierarchical MOx nanosheets structures, different types of ligand connections were used as sacrificial templates. Universally, Ni-MOF and Co-MOF precursors can be obtained via solvothermal complexation reacting metal salts (Ni2+ and Co2+) and benzoic acid ligands in N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) solution, respectively. The Fe-MOF precursor was prepared by optimizing the Prussian blue analog layered structure19. Subsequent, the sacrificial templates were calcined away at 450°C for 2 h to form 2D porous MOx nanosheet structures. GaN NPs were obtained by using a solvothermal method and controlled nitridation process. Subsequently, GaN NPs can be anchoring on the MOF-derived MOx surface by a spontaneous self-assembly process in DMF solution to form the MOx/GaN heterojunction (weight ratio = 1:1). The last step, the gas sensor arrays to be prepared by spin-coating MOx/GaN on Au inter-finger electrodes, respectively (Supporting Information S1). The sensor features overall dimensions of 4 × 8 mm, with both the electrode and gap widths being 0.2 mm (Fig. S1).

Characterization and testing methods

The morphology of samples was observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM-7900 F) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL-F200). The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) was executed by NETZSCH STA449F5. The crystal structure was analyzed by an X-ray diffraction (XRD, Aeris) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å). X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS) and valence band (VB) were performed using a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB Xi+ with an Al anode as a source. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area tests were conducted using the ASAP 2460. The Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM) were measured by NT-MDT. The Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV–vis) diffuse reflectance spectra were recorded on a UV 3600I plus with an integrating sphere and with BaSO4 as reference.

Gas-sensing tests were performed using the DGL-III dynamic gas-liquid distribution system. The tests were performed at RT (25 °C) and 20% relative humidity (RH). NO2, SO2, NH3, and CO2 serves as the standard gas for dehumidification and was purchased from Taiyuan Taineng Gas Co., Ltd. Trimethylamine (TMA) and C2H6O are injected into the gas path through the evaporator as liquids.

DFT calculation

In this work, the calculations were performed by DFT based on the Materials Studio. To enable facile understanding of the charge transfer and adsorption energies in the DFT studies, finite heterostructure models of the MOx/GaN system was studied using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Wang 1991 (PW91) functional basis set. To inhibit vertical interlayer interaction, vacuum layers exceeding 20 Å were introduced in the heterostructure models. A high standard is maintained for the accuracy in both energy calculations and structural optimization with a cut-off energy value of 500 eV. The energy convergence criterion is 1 × 10−5 eV, and the structural optimization stops when the force on the atoms is less than 0.02 eV·Å−1. The adsorption energy (Eads) calculation was utilized by the below equation20

Where \({E}_{{{MO}}_{{\rm{{\rm X}}}}/{GaN}}\) is the total energy of MOx/GaN heterostructure, \({E}_{{gas}}\) is the energy of the individual NO2 gas molecule.

Results and discussion

Morphological and structural characterization

Fig. 1b1–b3 present typical SEM images of MOF-derived MOx nanosheets. The strong coordination of the organic ligands significantly promotes the lamellar stacking of the MOF materials, resulting in a significant increase in thickness and an enlargement of the lateral dimensions (Fig. S2). After calcination treatment, the surface of MOF-derived MOx becomes rougher and still maintains the morphology of 2D nanosheets due to the carbonization of the organic ligand become carbon dioxide13. The substantial aspect ratio creates efficient channels for rapid electron transfer, significantly improving the dynamic behaviors of the gas sensing process. The GaN NPs with rough surface and good dispersion were successfully prepared as shown in Fig. S3. The OH- structures of citric acid have a strong complexing ability, which can form stable complex with Ga3+ and synergize with the amino hydrophilic group in urea to promote the homogenization of grain size. The MOx/GaN samples and their locally enlarged SEM reveal a large number of GaN NPs with average particle size of 475 nm are uniformly clustered on the surface of MOx nanosheets, forming compact nanosheet-particles hybrid structures (Fig. 1c1-c3).

To further study the optimal oxidation conditions and thermal decomposition profiles of MOF derivatives, TGA of pure Fe-MOF, Co-MOF, and Ni-MOF samples were performed under air atmosphere (Fig. 1d1–d3). The TGA and DTG curves reveal three weight loss steps. The weight loss of ΔW1 and ΔW2 is due to the decomposition of residual water and organic solvents in the sample, while the mass loss of ΔW3 is caused by the decomposition of organic ligands21. The decomposition process appears to be nearing completion at around 400°C for all MOFs as the TG and DTG curves gradually stabilize above this temperature. Therefore, the calcination condition of MOFs was set at 450 °C for 2 h at air atmosphere to obtain MOF-derived MOx.

The crystal structure of the prepared samples was analyzed by XRD as shown in Fig. 1e1–e3. According to this figure, the diffraction peaks of the three calcined Fe-MOF, Co-MOF, and Ni-MOF samples all identical to the pure Fe2O3 (JCPDS: 39-1346)22, Co3O4 (JCPDS: 42-1467)23, and NiO (JCPDS: 89-7390)24. Meanwhile, no additional impurity peaks were observed in the MOx diffraction peaks, suggesting that the self-sacrificial templates were completely transitioned to Fe2O3, Co3O4, and NiO. Moreover, extra hexagonal GaN diffraction peaks (JCPDS: 50-0792)25 were successfully identified in the MOx/GaN nanocomposites, indicating that GaN NPs were loaded effectively onto MOx nanosheets.

TEM was examined to further observe the microstructures and crystal of Fe2O3/GaN, Co3O4/GaN, and NiO/GaN. The morphology of hierarchical porous nanosheets are clearly revealed by contrast dark regions and shallow spaces (Fig. 2a1–b3), and the GaN NPs were successfully assembled onto the nanosheets surface to form heterogeneous structures, which is conducive to the adsorption and diffusion of target gases. Interestingly, by tuning the kind of ligand connection, the microstructure of MOF-derived MOx nanosheet appeared significantly different, which may lead to a different specific surface area and provide diverse path types for electron transfer. According to the typical high-resolution TEM images of Fig. 2c1–c3, the measured lattice spacings of 0.21 nm and 0.29 nm correspond to the (400) and (100) planes of Fe2O3 and GaN. The lattice fringes of 0.23 nm and 0.24 nm can be matched with the (400) and (100) planes of Co3O4 and GaN. The interplanar spacings of 0.25 nm and 0.26 nm are in good agreement with the (400) and (100) planes of NiO and GaN, respectively. Alternatively, the distinct interface authenticates the formation of the intimately coupled heterojunction between MOx nanosheets and GaN NPs. The element mapping images of Fe2O3/GaN, Co3O4/GaN, and NiO/GaN confirms the simultaneous presence and uniform distribution of MOx and GaN components (Fig. 2d1–d3). The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distributions of gas-sensing samples were also investigated (Fig. S4). Consequently, the calculated BET specific surface area of MOx/GaN samples were significantly improved after composite GaN NPs. Meanwhile, all the isotherms displayed a type-IV isotherm with typical H3 hysteresis loops, indicating the successful formation of mesoporous structures26. The substantial surface area and mesoporous structures create a large number of active sites for target gas adsorption.

The surface chemical states of the pure MOx and MOx/GaN samples were analyzed by XPS, all the core peaks have been calibrated by C 1 s (284.8 eV). As shown in Fig. 3a1–a3, the dominant peaks of Fe 2p, Co 2p, and Ni 2p are located around 711.3, 779.7, and 855.2 eV, respectively, while the appearance of additional Ga 2p1 (1148 eV), Ga 2p3 (1121 eV), Ga 3 d (22 eV), and N 1 s (424 eV) peaks in the MOx/GaN samples confirm the co-exist of MOx and GaN components27,28. The deconvoluted Fe2p, Co 2p, and Ni 2p spectrum of the samples are shown in Fig. 3b1–b3. Compared to the pure MOx samples, the overall peak of MOx/GaN shifted to lower energies, suggesting that MOx act the electron acceptor in the heterostructures as a whole, resulting in the formation of more electron-rich environments29. In the Ni 2p spectrum of NiO, the peaks at 854 and 855.8 eV correspond to Ni2+ 2p3/2 and Ni3+ 2p3/2, and the peaks at 872.2 and 874 eV are assigned to Ni2+ 2p1/2 and Ni3+ 2p1/2, respectively. Interestingly, the significant variation in peak structure was observed on the NiO/GaN spectrum (Fig. 3b2), which is due to the formation of heterostructures at the p-type dominated NiO interfaces, and the movement of holes contributed to the conversion of Ni3+ to Ni2+ valence state30. The shift of XPS peaks implies the chemical interaction and charges transfer between MOx and GaN in the nanocomposites, suggesting the formation of heterostructures, which is conducive to the enhancement of gas-sensing response31. The O1s spectra of were resolved as lattice oxygen (OL), vacancy oxygen (OV), and chemisorbed oxygen (OC) in Fig. 3c1–c3, respectively. Moreover, it is well accepted that the more OC species have a significant effect on the sensing performance by the direct oxidation-reduction processes with target gas32. Accordingly, the relative percentage of OC for MOx/GaN is larger than pure component, and Fe2O3/GaN has the highest OC content (18.7%), this phenomenon is considered to be a crucial factor contributing to the superior gas sensing.

Gas-sensing performances

To test the gas sensing performances of the heterostructures, we fabricated 3*2 chemoresistive gas sensor arrays using the MOx/GaN heterojunction discussed above. As we know, RT detection contributes to low power consumption and long-term stability of gas sensors. We selected NO2 as the target gas due to its strong binding behaviors even at RT, which permits us to assess the dynamic adsorption properties and inner sensing channel33. In addition, NO2 can act as a biomarker of nitrification products and oxidative stress in exhaled gas of lung patients to assess disease and environmental exposure levels34,35,36. Although various gas sensors have shown promising performance for NO2 gas detection, high-temperature operation and irreversible sensing are still major challenges37,38. Benefiting from the unique heterostructures and electrochemical properties of MOx/GaN gas sensors, we carried out gas-sensing tests toward NO2 gas at RT and 20% RH to validate the sensor’s performance.

Firstly, we optimization of the hybridization ratio of the heterogeneous components. Upon weight ratio between MOx and GaN reach to 1:1, we interestingly find that the sensors exhibited the highest response (ΔR/Rair×100%) to 200 ppm NO2 (Fig. S5). Evidently, appropriate GaN NPs hybridization degree can improve the coordination of heterostructures. However, excess GaN NPs may cover the active sites on the MOx nanosheet surface and form independent electron transfer pathway, thus reducing the number of NO2 molecules adsorbed in the nanocomposites. Therefore, we chose MOx/GaN with weight ratio of 1:1 as the target sensors during the following testing.

As shown in Fig. 4a1–a3, compared with the pure MOF-derived MOx component, all the MOx/GaN sensors exhibited higher response, faster response and recovery times toward 200 ppm NO2 at RT. The dynamic resistance variation curves of Fe2O3, Co3O4, NiO, and their composite components to different concentrations NO2 gas are shown in Fig. 4b1–b3 and Fig. 4c1–c3. After exposure to NO2 gas, the resistances of sensors drop sharply, exhibiting MOx-dominated p-type semiconductor characteristics39. Meanwhile, all the sensors exhibit an extremely low 1 ppb limit of detection (LOD), and the corresponding response values are well fitting to the Langmuir isothermal curve as the NO2 concentration varies from 200 ppm to 1 ppb. Nevertheless, after hybridization with GaN NPs, all heterostructure sensors exhibited more dynamic resistive behavior and reversibility enhancement. This behavior underscores the importance of the additional hole accumulation layers introduced by heterostructures and utilizing porous MOx nanosheet to hybridize with GaN NPs synergistically enhance sensing response and reversibility (Fig. S6). Notably, among all hybrid combinations, Fe2O3/GaN displayed the highest sensitivity (ΔR/Rair = 89.4%) and fastest response time (10 s) to 200 ppm NO2, which is attributed to its largest surface area (197.6 cm3/g) and the unique lamellar structure that creates more active sites for NO2 adsorption and rapid electron transport (Fig. 4e). Our experimental results show that the MOx/GaN sensors exhibit superior NO2 detection ability compared to other advanced heterostructures gas sensors (Table S1).

a1–a3 Response time of pure MOx vs. MOx/GaN toward 200 ppm NO2; (b1–b3) Dynamic resistance curve of MOx sensor toward various concentration NO2 gas (insets are Langmuir fitted curves); (c1–c3) Dynamic resistance curve of MOx/GaN sensor toward various concentration NO2 gas (insets are Langmuir fitted curves); (d1–d3) Repeatability curves of MOx/GaN sensor; (e) Response comparison of MOx/GaN sensors; (f) Selective radar chart; (g) Moisture sensitive properties; (h) Long-term stability

To further investigate the NO2 sensing performance, the repeatability curves of the MOx/GaN sensors were tested in Fig. 4d1–d3. The response of the three sensors remained constant and exhibited reversible and stable characteristics during exposure to 100, 1, and 0.01 ppm NO2 cycles, respectively. In order to evaluate the anti-interference of MOx/GaN sensor arrays, we investigated the selectivity by testing various gases at RT. Since certain inflammatory diseases such as asthma, chronic lung disease, and lung cancer may result in elevated fractional exhaled disease marker gases (e.g., NOx, ammonia (NH3), trimethylamine (TMA), sulfuretted hydrogen (H2S), etc.)40,41. Therefore, we chose several common exhaled target gases (NH3, TMA, H2S, alcohol (C2H6O)) and respiratory CO2 alteration intervals (400 ppm~5%) in human exhaled as selectivity gases in Fig. 4f. Obviously, both the three sensors possessed the obvious response to NO2, NH3, and TMA, indicating the excellent selectivity and application potential for exhaled gas detection.

Humidity is one of the major factors affecting sensing performance, and the high RH (65–90%) in exhaled gases poses a significant challenge to gas sensors42. The response values, water contact angle, and dynamic humidity resistance curves of the sensors were investigated in Fig. 4g and Fig. S7. It is noteworthy that the MOx/GaN sensors still maintain a high response and complete response/recovery process even under high humidity conditions, with response decreases of only 0.59%, 0.51%, and 0.51% per 1% RH for Fe2O3/GaN, Co3O4/GaN, and NiO/GaN, respectively. This may be due to the accumulation of holes reducing the electron supply capacity of metal ions and chemisorbed oxygen at the heterojunction interface, thereby weakening their electron exchange reactions with water molecules. Consequently, chemisorbed oxygen exhibits stronger competitive adsorption capabilities than water molecules on the surface of sensitive layer43. The high humidity anti-interference contributes to the further breath testing applications of MOx/GaN sensor arrays. Long-term stability was also investigated in Fig. 4h, where the response values fluctuated of Fe2O3/GaN (11.4%), Co3O4/GaN (10.2%), and NiO/GaN (12.7%) to 200 ppm NO2 were very little within 100 days, indicating long-term excellent stability.

Gas sensing mechanism

The key to synergistically employing both semiconductors in our hybridization structures is the electronic characteristic at the heterojunctions formed between MOx and GaN, as well as the distribution of such heterojunctions throughout the sensors. Particularly, the activation energy for carrier transport during NO2 adsorption is pivotal for enhancing the sensing performance. Given the fast response and excellent signal recovery of the MOx/GaN sensors at room temperature, we attempted to mechanistically understand the effect of the sensitive unit on the adsorption and desorption behavior of NO2 gas. The VB of MOx and GaN can be measured by VB-XPS spectra, which are determined to be 0.81 (Fe2O3), 0.63 (Co3O4), 0.58 (NiO), and 1.88 eV (GaN) below their Fermi levels, respectively (Fig. S8). Based on the UV-vis absorption spectra of MOx and GaN samples, their bandgaps are calculated to be 2.0 (Fe2O3), 1.84 (Co3O4), 1.75 (NiO), and 3.19 eV (GaN), respectively (Fig. S9). The sensor work function (Øsample) is determined by the difference between surface contact potential difference (CPD) and the KPFM tip potential (ØTip) in Fig. 5a and Fig. S10. Highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) features a smooth surface with excellent electrical conductivity, providing a clean, electrically stable, and calibratable reference platform for KPFM measurements. A potential difference of 0.024 eV was measured on the HOPG surface by applying voltage via KPFM. The ØTip was calibrated against the standard HOPG value (4.6 eV) and calculated to be 4.62 eV 44.

The electronic band structures of the heterostructures were constructed collectively as Fig. 5b. Obviously, we can clearly demonstrate the n-type semiconductor property of GaN and the p-type semiconductor property of MOx by the position of the Fermi energy level and gas-sensing performances45. When the contact occurs, since all the three MOx have higher work function than GaN NPs, and electrons can spontaneously transfer from n-GaN NPs to p-MOx (while holes migrate into the n-GaN) until the Fermi levels are aligned, leading to the separation of electrons and holes and the formation of charge depletion layers (HDL) and hole accumulation layers (HAL)29. In air atmosphere, O2 molecules are adsorbed on the surface of the sensors, trapping the electron and being ionized and decomposed into O2−. As a result, hole deposits form on the surface of HAL, and the resistance decreases in the process. In NO2 atmosphere, NO2 molecules extracts electrons from the heterostructures surface and decrease their charge concentration, which makes the extra holes return to MOx without any further restrictions until the equilibrium is attained. During this adsorption process, additional holes accumulate on MOx nanosheets surface, and the thickness of the HAL formed at the interface between GaN NPs and the MOx sheet can be hugely modulated (thicken), inducing a rapid decrease of resistance (Fig. 5c). Notably, among the three heterostructures, Fe2O3/GaN possessed the highest barrier energy and resistance reduction degrees, thus achieving the highest sensitivity and the fastest response time.

To further gain insight into the effect of MOx/GaN on the above sensing behaviors, the binding energies between the gas molecules and the heterostructures were evaluated by DFT46. For clarity, we considered the heterostructures as divided into GaN and MOx surfaces, studying the most probable gas adsorption sites as shown in Fig. 5d. The adsorption energy of O2 was calculated to reveal the interaction strength between Oc and the heterojunction interface. By comparing across all the heterostructures, we found that the NO2 molecule draws the most charge from Fe2O3/GaN, implying the strongest interaction between Fe2O3/GaN and NO2. This favorably corresponds to the most outstanding response and recovery behavior of Fe2O3/GaN among the three MOx/GaN heterostructures analyzed above. The calculation results also supported our rationale of 2D MOx nanosheets dominated hole-enrichment as a major contributor to NO2 adsorption, and the synergistic effect of the 2D MOx nanosheets and GaN NPs provides a superior platform for NO2 sensing. The heterostructure construction strategy we report here is more straightforward and holds the potential to be generalized onto any MOF-derived MOx/wide bandgap semiconductor nanostructures.

Exhaled gas disease analysis assistant with ensemble learning

In order to realize portable and rapid analysis of human exhaled gas, an intelligent exhaled gas detection device (size: 204×175 mm) equipped with a 3*2 MOx/GaN gas sensor array and an active sampling gas path was developed for potential respiratory disease diagnosis in Fig. 6a. The active sampling gas path consists of a sampling gas path, an exhaust gas path, and a CO2 detection path (Fig. 6b). The gas pump controls exhaled gas into the sampling gas path and reacts with the gas sensor array. In order to ensure that the exhaled gas is alveolar gas, an infrared CO2 sensor is used to control the concentration of exhaled gas to reach the threshold47, and then turn on the sampling gas pump. After 20 s of exhaled gas detection, the exhaust gas pump is turned on and fresh air is passed through the check valve at a flow rate of 200 ml/min to clean the chamber. The sampling gas path and exhaust gas path are switched via a three-way valve. The cleaning lasts 25 s, and the exhaled gas detection process completes.

The PCB layout of the sensing circuit is shown in Fig. 6c, which consists of MOx/GaN gas sensor arrays, a voltage acquisition unit, and an environmental sensing unit. The 3*2 gas sensor array module encapsulated in a three-dimensional (3D) printed gas chamber (size: 28 × 45 × 5 mm) made by low-adhesion polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFT) to minimize the adsorption of gas molecules by the chamber. The voltage acquisition unit employs a voltage divider combined with a voltage follower, specifically designed for the resistance variation range of semiconductor gas sensors. A TLC2274AIDR four-channel precision amplifier is used to form the voltage follower, which helps minimize the PCB area. An environmental sensor unit is formed using a temperature-humidity sensor (Sensirion-SHT30) and a barometric pressure sensor (Bosch-BMP280) to further perform environmental compensation of the gas sensor.

Benefiting from the excellent gas-sensing performance and stability, exhaled gas detection device can be applied to analyze human exhaled gas for potential diagnostic confirmation of respiratory diseases. The representative breath detection process is shown in Fig. 7a, clinical exhaled samples tested from 8 patients with lung cancer and 5 healthy volunteers were analyzed, each patient conducted two exhaled tests to extended data set (Table S2). During testing, standardized breath sampling should also be of concern. All participants maintained an empty stomach for 8 h and rinsed their mouths with deionized water before the test. Considering the feature of MOx/GaN gas sensors, we try to use the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) deep learning model to classify clinical patients and healthy subjects. The LSTM possesses excellent abilities in process time-series data and capture long-term dependencies which is the characteristic of sensor data48. Single sensor signals were built by LSTM model, and the disease analysis is further realized through ensemble-learning-assisted sensor arrays. Three of sensors (Fe2O3/GaN, Co3O4/GaN, and NiO/GaN) were used to train deep learning model, and other three sensors were used to verify the performance of the constructed model. Finally, the ensemble learning is deployed to improve the accuracy of disease prediction. (Fig. 7b).

a Breath sampling process; (b) Ensemble learning network architecture; (c) Exhaled gas test curves of clinical patients; (d) Exhaled gas test curves of healthy volunteers; (e) Exhaled gas test results; (f) LSTM model train accuracy and loss; (g) The confusion matrix of clinical patients and healthy volunteers

Response calculations of the exhaled gas detection device can be found in Table S3. The test curves of exhaled gas of clinical patients and healthy volunteers are shown in Fig. 7c, d, it can be seen that the gas detection device we built can achieve stable detection of the exhaled gas signal. The response box-plot statistics of test results are shown in Fig. 7e, and the response signals of the detected patients are significantly higher than those of the healthy population. Interestingly, we found the fact that the response values of the patients were more centralized than those of the healthy people. This may be due to the sensor’s specific recognition of disease-marking gases exhaled by patients, whereas signal differences in healthy populations are mainly influenced by airflow and temperature. Furthermore, the exhaled gas response signal is a superposition of disease biomarker gas signals and humidity response. By processing signals from the gas sensor array using an LSTM model, the characteristic interference from humidity signals can be uniformly incorporated to identify differences between patients and healthy individuals. Firstly, use moving average algorithm to eliminate outliers, after that, use down sampling to reduce number of data points to improve computing efficiency and reduce computing difficulty, after down sampling the input dimension is reduced to 24. The LSTM model has fully converged after the 44th epochs of training with a maximum accuracy of 95.8% (Fig. 7f). Notably, we unify the effects of humidity and marker gases to the LSTM algorithm for superior recognition accuracy. The result of the model training and the confusion matrix of the integrated training in Fig. 7g, where the constructed sensor array can accurately achieve the distinction between clinical patients and healthy people (T is patient probability, F is healthy probability). Hence, the exhaled gas disease detection technical that we proposed confirms the promising potential in the early diagnosis of diseases and the construction of exhaled gas fingerprints.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a new breath detection device with an active sampling gas path combined with a 3*2 MOx/GaN heterojunction gas sensor array, and successfully performed clinical patient exhaled gas detection. The confusion matrix labels for lung cancer patients and healthy people were successfully constructed with an accuracy of 95.8% under the assistance of ensemble learning. The new heterojunction sensing arrays were designed by anchoring n-GaN nanoparticles on three MOF-derived p-MOx porous nanosheets via an efficient self-assembly process. A series of morphological and structural characterizations were executed to demonstrate the successful formation of heterostructures. The MOx/GaN sensor arrays exhibited remarkable response speed (10 s), excellent repeatability, extreme anti-humidity, and a lower detection limit of 1 ppb toward NO2 gas at room temperature. Energy band structure combined with DFT calculations are used to analyze the introduction of additional hole-accumulating layers and the abundance of surface-active sites are the main reasons for the improved gas-sensing performance. Therefore, this work provides an innovative technology for the construction of heterogeneous sensor arrays and exhaled gas detection device, which has a promising application prospect in the field of early disease diagnosis and IoMT.

Supplementary information: Supplementary material (Preparation details; SEM of MOF precursor and GaN NPs; BET; resistance transitions of different ratio sensors and GaN NPs; comparison of sensing performance; anti-humidity characteristic; test results of VB-XPS, UV-Vis, and KPFM; clinical testing information) is available in the online version.

References

Jain, S. et al. Internet of medical things (IoMT)-integrated biosensors for point -of -care testing of infectious diseases. Biosens. Bioelectron. 179, 113074 (2021).

Chaudhary, V. et al. Nose-on-chip nanobiosensors for early detection of lung cancer breath biomarkers. Acs Sens. 9, 4469–4494 (2024).

Güntner, A. T. et al. Breath sensors for health monitoring. Acs Sens. 4, 268–280 (2019).

Gashimova, E. et al. Exhaled breath analysis using GC-MS and an electronic nose for lung cancer diagnostics. Anal. Methods 13, 4793–4804 (2021).

Zhou, X. Y., Qi, M. Q., Li, K., Xue, Z. J. & Wang, T. Gas sensors based on nanoparticle-assembled interfaces and their application in breath detection of lung cancer. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 4, 101678 (2023).

Liu, K., Lin, M., Zhao, Z. H., Zhang, K. W. & Yang, S. Rational design and application of breath sensors for healthcare monitoring. Acs Sens. 10, 15–32 (2024).

He, X. X. et al. Metal oxide semiconductor gas sensing materials for early lung cancer diagnosis. J. Adv. Ceram. 12, 207–227 (2023).

Zong, B. Y. et al. Smart gas sensors: recent developments and future prospective. Nano-Micro Lett. 17, 54 (2025).

Cheng, Y. D. et al. Advances in metal-organic framework-based membranes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 8300–8350 (2022).

Jo, Y. M. et al. MOF-based chemiresistive gas sensors: toward new functionalities. Adv. Mater. 35, 2206842 (2023).

Zhai, Y. X. et al. Excellent sensing platforms for identification of gaseous pollutants based on metal-organic frameworks: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 484, 149286 (2024).

Peng, X. Y., Wu, X. H., Zhang, M. M. & Yuan, H. Y. Metal-organic framework coated devices for gas sensing. Acs Sens. 8, 2471–2492 (2023).

Yao, M. S., Li, W. H. & Xu, G. Metal-organic frameworks and their derivatives for electrically-transduced gas sensors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 426, 213479 (2021).

Wang, D. Y. et al. Multifunctional latex/polytetrafluoroethylene-based triboelectric nanogenerator for self-powered organ-like MXene/Metal-organic framework-derived CuO nanohybrid ammonia sensor. Acs Nano 15, 2911–2919 (2021).

Jang, J. S., Koo, W. T., Kim, D. H. & Kim, I. D. In situ coupling of multidimensional MOFs for heterogeneous metal-oxide architectures: toward sensitive chemiresistors. Acs Cent. Sci. 4, 929–937 (2018).

Shao, X. Y. et al. Recent advances in semiconductor gas sensors for thermal runaway early-warning monitoring of lithium-ion batteries. Coord. Chem. Rev. 535, 216624 (2025).

Jiang, Y. et al. A comprehensive review of gallium nitride (GaN)-based gas sensors and their dynamic responses. J. Mater. Chem. C. 11, 10121–10148 (2023).

Liu, L. L. et al. Structural morphology and surface recrystallization properties of GaN nanoparticles with different sizes during sintering. Ceram. Int. 49, 32292–32300 (2023).

Xu, L. Y. et al. One-step coprecipitation synthesis of titanium hexacyanoferrate nanosheet-assembled hierarchical nanoflowers for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Acs Appl. Nano Mater. 6, 19997–20005 (2023).

Zhang, D. Z., Wu, J. F., Li, P. & Cao, Y. H. Room-temperature SO2 gas-sensing properties based on a metal-doped MoS2 nanoflower: an experimental and density functional theory investigation. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 20666–20677 (2017).

Healy, C. et al. The thermal stability of metal-organic frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 419, 213388 (2020).

Karuppasamy, K. et al. Room-temperature response of MOF-derived Pd@PdO core shell/γ-Fe2O3 microcubes decorated graphitic carbon based ultrasensitive and highly selective H2 gas sensor. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 652, 692–704 (2023).

Jo, Y. M. et al. Metal-organic framework-derived hollow hierarchical Co3O4 nanocages with tunable size and morphology: ultrasensitive and highly selective detection of methylbenzenes. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 8860–8868 (2018).

Zhang, Y. K. et al. Morphology-modulated rambutan-like hollow NiO catalyst for plasma-coupled benzene removal: enriched O species and synergistic effects. Sep. Purif. Technol. 306, 122621 (2023).

Chen, S. J. et al. Direct growth of polycrystalline GaN porous layer with rich nitrogen vacancies: application to catalyst-free electrochemical detection. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 53807–53815 (2020).

Duan, P. Y. et al. MOF-derived xPd-NPs@ZnO porous nanocomposites for ultrasensitive ppb-level gas detection with photoexcitation: design, diverse-scenario characterization, and mechanism. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 660, 974–988 (2024).

Fan, Y. Z. et al. Synthesis and gas sensing properties of β-Fe2O3 derived from Fe/Ga bimetallic organic framework. J. Alloy. Compd. 921, 166193 (2022).

Sun, H. M., Tang, X. N., Zhang, J. R., Li, S. & Li, L. MOF-derived bow-like Ga-doped Co3O4 hierarchical architectures for enhanced triethylamine sensing performance. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 346, 130546 (2021).

Liang, Z. P. et al. A 2D-0D-2D sandwich heterostructure toward high-performance room-temperature gas sensing. Acs Nano 18, 3669–3680 (2024).

Zhang, D. et al. Small size porous NiO/NiFe2O4 nanocubes derived from Ni-Fe bimetallic metal-organic frameworks for fast volatile organic compounds detection. Appl. Surf. Sci. 623, 157075 (2023).

Zhao, Q. N. et al. Edge-enriched Mo2TiC2Tx/MoS2 heterostructure with coupling interface for selectively NO2 monitoring. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2203528 (2022).

Liu, F. et al. -Fe2O3 derived from metal-organic frameworks as high performance sensing materials for acetone detection. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 403, 135147 (2024).

Roh, H. et al. Robust chemiresistive behavior in conductive polymer/MOF composites. Adv. Mater. 36, 2312382 (2024).

Kwiatkowski, A., Borys, S., Sikorska, K., Drozdowska, K. & Smulko, J. M. Clinical studies of detecting COVID-19 from exhaled breath with electronic nose. Sci. Rep. 12, 15990 (2022).

Eum, K. D. et al. Long-term NO2 exposures and cause-specific mortality in American older adults. Environ. Int. 124, 10–15 (2019).

Masri, F. A. et al. Abnormalities in nitric oxide and its derivatives in lung cancer. Am. J. Respirat. Crit. Care Med. 172, 597–605 (2005).

Li, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Jiang, Y. & Yi, J. X. Superior NO2 sensing of MOF-derived indium-doped ZnO porous hollow cages. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 37489–37498 (2020).

Majhi, S. M. et al. MOF-derived SnO2 nanoparticles for realization of ultrasensitive and highly selective NO2 gas sensing. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 419, 136369 (2024).

Choi, B., Shin, D., Lee, H. S. & Song, H. Nanoparticle design and assembly for p-type metal oxide gas sensors. Nanoscale 14, 3387–3397 (2022).

Holterman, C. E., Read, N. C. & Kennedy, C. R. J. NOx and renal disease. Clin. Sci. 128, 465–481 (2015).

Yang, L. et al. Moisture-resistant, stretchable NOx gas sensors based on laser-induced graphene for environmental monitoring and breath analysis. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 78 (2022).

Mansour, E. et al. Measurement of temperature and relative humidity in exhaled breath. Sens. Actuat. B Chem. 304, 127371 (2020).

Wang, D. Y. et al. Electrospinning of flexible poly(vinyl alcohol)/MXene nanofiber-based humidity sensor self-powered by monolayer molybdenum diselenide piezoelectric nanogenerator. Nano-Micro Lett. 13, 57 (2021).

Huynh, T. M. T., Nguyen, L. & Phan, T. H. Tuning the morphological and electrical properties of graphite surface by self-assembled viologen nanostructures. Surf. Sci. 723, 122122 (2022).

Kahn, A. Fermi level, work function and vacuum level. Mater. Horiz. 3, 7–10 (2016).

Shao, X. Y., Zhang, D. Z., Tang, M. C., Zhang, H., Wang, Z. J., Jia, P. L. & Zhai, J. S. Amorphous Ag catalytic layer-SnO2 sensitive layer-graphite carbon nitride electron supply layer synergy-enhanced hydrogen gas sensor. Chem. Eng. J. 495, 153676 (2024).

West, J. B. State of the art: ventilation-perfusion relationships. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 116, 919–943 (1977).

Xu, N. K., Wang, X. Q., Meng, X. R. & Chang, H. Q. Gas concentration prediction based on IWOA-LSTM-CEEMDAN residual correction model. Sensors 22, 4412 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO.62031022,52375572), Shanxi-Zheda Institute of Advanced Materials and Chemical Engineering (2022SX-AT001), Key Core Technological Breakthrough Program of Taiyuan City (2024TYJB0126), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFB1314001), and the Central Guidance Fund for Local Scientific and Technological Development Projects (YDZJSX2024D020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D., Wang, W., Duan, Q. et al. Ensemble-learning-assisted exhaled gas disease analysis based on in-situ construction of MOF-derived MOx/GaN heterojunction sensor arrays. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 39 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01150-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01150-8