Abstract

This study aims to characterize cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in women living with HIV using biomarkers. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for human papillomavirus (HPV) E4 protein indicates CIN with productive HPV infection, whereas Ki-67 and p16ink4a indicate CIN with transforming characteristics, which may be further characterized using DNA hypermethylation, indicative for advanced transforming CIN. Cervical biopsies (n = 175) from 102 HPV positive women living with HIV were independently reviewed by three expert pathologists. The consensus CIN grade was used as reference standard. IHC staining patterns were scored for Ki-67 (0–3), p16ink4a (0–3), and E4 (0–2) and correlated to methylation levels of four cellular genes in corresponding cervical scrapes. Reference standards and immunoscores were obtained from 165 biopsies:15 no dysplasia, 91 CIN1, 31 CIN2, and 28 CIN3. Ki-67 and p16ink4a scores increased with increasing CIN grade, while E4 positivity was highest in CIN1 and CIN2 lesions. E4 positive CIN1 lesions had higher Ki-67 and p16ink4a scores and higher methylation levels compared with E4 negative CIN1 lesions. E4 positive biopsies with low cumulative Ki-67/p16 ink4a immunoscores (0-3) had significantly higher methylation levels compared with E4 negative biopsies. No significant differences in Ki-67 and p16ink4a scores and methylation levels were observed between E4 negative and positive CIN2 or CIN3 lesions. The presence of high methylation levels in scrapes of CIN lesions with IHC characteristics of both productive (E4 positive) and transforming infections (increased Ki-67/p16ink4a expression) in women living with HIV might indicate a rapid aggressive course of HPV infections towards cancer in these women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer diagnosed in women worldwide, mostly affecting low- and middle-income countries, and one of the most common cancers in women living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [1]. Cervical cancer is caused by a persistent infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) [2], and both are significantly more prevalent in women living with HIV compared with the general population [3,4,5]. Moreover, cervical cancer occurs at a younger age in women living with HIV, indicating earlier oncologic progression [6]. In South Africa, where HIV and HPV infection rates are among the highest worldwide, cervical cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in women [7].

Cervical cancer develops through preinvasive stages, referred to as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN, grade 1–3), which can be detected and treated via cervical screening. Histological classification of cervical lesions is based on morphological features in H&E stained slides alone and may be supported by p16inka4 and Ki-67 immunohistochemical (IHC) staining in difficult cases [8, 9]. Clinical management is based on the CIN grade. However, grading of CIN lesions is only moderately reproducible due to the subjective interpretation of cellular abnormalities [10]. The majority of CIN1 lesions are associated with productive HPV infections, with a high regression rate (up to 60%) and a low progression risk to invasive cancer (about 1%), whereas most CIN3 lesions are associated with transforming infections, having a lower regression rate (about 30%) and a progression rate to invasive cancer of up to 30% [11, 12]. CIN2 lesions are particularly heterogeneous in both clinical behavior and chromosomal aberrations, including both transient productive and early transforming infections [13, 14]. Current clinicopathological classifications are unable to predict which lesions are likely to progress and, consequently, both CIN3 and CIN2 lesions are treated by ablative or excisional therapy in many countries. This results in considerable overtreatment and associated cervical morbidity [15]. The heterogeneity of CIN lesions can be shown by using IHC markers of productive HPV infection (HPV E4) and transforming HPV infection (Ki-67 and p16ink4a overexpression as a result of HPV E7 activity) [16].

Another biomarker associated with transforming HPV infections and cervical cancer is methylation of promoter regions of host cell genes. Methylation-mediated silencing of host cell genes involved in cervical carcinogenesis, detected by methylation levels of promoter regions of such genes, has shown to increase with increasing CIN grade and methylation levels are very high in cervical cancer [14]. Moreover, several studies have shown that, in HIV-uninfected women, the presence of high methylation levels is associated with increasing chromosomal aberrations, similar to cervical cancer, suggesting that high methylation levels are associated with underlying lesions with a high short-term progression risk for cancer [17,18,19].

Few studies on Ki-67 and p16ink4a expression and their diagnostic performance in women living with HIV have been published [20,21,22]. Moreover, studies evaluating the expression of HPV E4, indicating a productive HPV infection with a low short-term progression risk, and methylation of host cell genes, indicating a transforming infection with a high short-term progression risk for cervical cancer, in CIN lesions of women living with HIV are limited and integrated analysis of these markers has not been described for this population.

In this study we aim to characterize CIN lesions in women living with HIV using markers characteristic for transforming (i.e., Ki-67 and p16ink4a expression) and productive infections (i.e., HPV E4 expression) In addition, we correlate the expression of these markers to the methylation levels of four host cell genes in the corresponding cervical scrapes in order to get insight in the aggressive nature of HPV-associated cervical lesions in women living with HIV.

Materials and methods

Study population

Clinical samples from a South African screening cohort of women living with HIV were used for this study. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Pretoria (protocol numbers 100/2012 and 155/2014) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Detailed study procedures and baseline characteristics have been described previously [23,24,25].

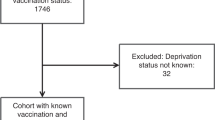

From all study participants a liquid-based cytology sample was collected, followed by two colposcopy-directed biopsies from either the most abnormal area on the cervix or at random if no lesion was visible. Samples from women who tested HPV positive on liquid-based cytology using a clinically validated HPV PCR assay (GP5 + /6 + -PCR EIA and/or HPV-Risk assay) were included, in total 273 biopsies from 144 women. Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the study procedures.

Immunohistochemistry

All formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded cervical biopsies were cut into seven sections of 3 um. The first and last sections were used for H&E staining to ensure presence of a lesion throughout all sections (sandwich technique). All biopsies were first classified by an expert pathologist (pathologist 1) based on morphologic characteristics as no dysplasia, CIN1, CIN2, CIN3, or invasive carcinoma (see paragraph ‘H&E CIN grading’). All biopsies with an H&E CIN grade by pathologist 1 of CIN1 or worse (175 biopsies from 102 women in total) were stained for Ki-67, p16ink4a, and HPV E4. In-between sections were used for immunostaining with mouse monoclonal antibodies against Ki-67 antigen (clone MIB-1, Dako, Agilent Technologies, USA) and p16ink4a antigen (clone E6H4™, CINtec®, Roche, Switzerland) using the automated Ventana staining machine (Ventana Benchmark ULTRA, Ventana Medical Systems, Roche, USA). Furthermore, sections were also stained with the validated mouse monoclonal antibodies panHPVE4 (FH1.1., further referred to as E4, produced in the laboratory of dr. J. Doorbar [26] and kindly provided by him, reactive against HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 67, and 70), as described previously [27].

Scoring of cervical biopsies

All 175 biopsies of women who tested HPV positive on liquid-based cytology were reviewed by three expert pathologists (pathologist 1, 2, and 3) who were blinded to the HPV and methylation results from the cervical scrapes.

H&E CIN grading

The pathologists reviewed the H&E slides of the biopsies, selected the area with the most dysplastic epithelial features, and graded the lesion based on morphologic characteristics (further referred to as ‘H&E CIN grade’). Biopsies were classified as no dysplasia, CIN1, CIN2, CIN3, or invasive carcinoma, according to international criteria [28].

Combined H&E and IHC CIN grading

The three pathologists then interpreted the Ki-67 and p16ink4a expression in the area with the most dysplastic epithelial features, and generated a CIN grade based on morphologic features combined with their interpretation of the Ki-67 and/or p16ink4a immunostainings (further referred to as ‘combined H&E and IHC CIN grade’). The consensus diagnosis of the combined H&E and IHC CIN grade based on agreement in at least two out of three pathologists, was used as the ‘reference standard’. If no majority agreement was reached, consensus was achieved in a panel discussion (in total 14 biopsies).

Scoring of Ki-67, p16ink4a, and E4

Two pathologists (pathologist 2 and 3) scored the expression of Ki-67 (score 0–3), p16ink4a (score 0–3), and E4 (score 0–2) in the most dysplastic area, as described previously [16, 27]. In brief, no increased Ki-67 nuclear staining, i.e., only staining of cells in the basal layer was scored 0, and increased Ki-67 staining up to the lower one-third, two-thirds, or more than two-thirds of the epithelium was scored as 1, 2, or 3, respectively. Negative or patchy (i.e., non-diffuse) p16ink4a staining was scored as 0 and diffuse staining up to the lower one-third, two-thirds, or more than two-thirds was scored as 1, 2, or 3, respectively. Using these scores, a cumulative Ki-67/p16ink4a immunoscore (0–6) was generated for each biopsy. E4 expression was scored as negative (0) in the absence of E4 positive epithelial cells, E4 positivity restricted to upper quarter of the epithelium was scored as focal [1], and E4 positivity in the upper one-third of the epithelium or more was scored as extensive [2].

Methylation analysis

Methylation analysis by quantitative methylation specific PCR (qMSP) on bisulfite converted DNA from cervical scrapes collected at baseline was performed previously [24, 29]. In this study, host cell genes ASCL1, LHX8, FAM19A4, and miR124-2, involved in cervical carcinogenesis, were evaluated. Methylation values off all targets were normalized to the reference gene B-actin (ACTB) and the calibrator using the comparative Ct method (2−∆∆Ct × 100), resulting in ∆∆Ct ratios [30].

Statistical analysis

Kappa statistics were used to assess the interobserver agreement between the different scoring methods (i.e., H&E CIN grade, combined H&E and IHC CIN grade, Ki-67 score, p16ink4a score, Ki-67/p16ink4a immunoscore, and E4 score) of the cervical biopsies of two pathologists (2 and 3), as they completed all scoring methods. Quadratic weighted kappa was calculated using the different categories of each scoring method and interpreted according to the standards of Landis and Koch [31].

Absolute and proportional scoring results of Ki-67, p16ink4a, and E4 from each pathologist were calculated for all biopsies and stratified by CIN grade based on the reference standard. Ki-67 and p16ink4a expression was compared between E4 negative and E4 positive (i.e., focal or extensive) biopsies, stratified by the reference standard, using Fisher’s exact analysis.

Methylation levels in cervical scrapes were correlated to the highest reference standard present in the corresponding biopsy of the same patient and, in case of two biopsies with the same reference standard, to the highest Ki-67/p16ink4a immunoscore, as the methylation levels are considered to represent the worst underlying cervical lesion [32]. The Mann–Whitney U testing was used to compare methylation levels in lesions with different Ki-67/p16ink4a and E4 expression patterns.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (V.22) and STATA (V.14), and p values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Results

In total 165 biopsies of 96 HPV positive patients had adequate H&E and IHC staining and were included in the analyses (Fig. 1). From these biopsies a reference standard was obtained, resulting in 15 biopsies with no dysplasia, 91 CIN1, 31 CIN2, and 28 CIN3.

Interobserver agreement

The results of each scoring method are presented in Supplementary Table 1. According to the standards of Landis and Koch [31], the different scoring methods had substantial to almost perfect agreement between pathologists 2 and 3, with weighted kappa values of 0.70, 0.74, 0.82, 0.84, and 0.82 for H&E CIN grade, combined H&E and IHC CIN grade, Ki-67, p16ink4a, and E4 scoring, respectively. Furthermore, the cumulative Ki-67/p16ink4a immunoscore had the highest agreement (weighted kappa 0.87). Because of this high interobserver agreement, only the scoring results of one pathologist (pathologist 3) are reported. Similar results were obtained when the scoring results of pathologist 2 were evaluated.

Expression patterns of Ki-67, p16ink4a, and E4 in cervical biopsies

Table 1 provides an overview of the expression of Ki-67, p16ink4a, and E4 stratified by reference standard. In biopsies with no dysplasia, Ki-67 and p16ink4a expression was normal in 46.7% and 100%, respectively, while in biopsies with CIN3, Ki-67, and p16ink4a were expressed in more than two-thirds of the lower epithelial layer in 67.9% and 71.4%, respectively. E4 positivity was mostly observed in CIN1 and CIN2 lesions: 37.4% of CIN1 and 71.0% of CIN2 were positive for E4 (16.5% and 32.3% with focal E4 expression (score 1), 20.9% and 38.7% with extensive E4 expression (score 2) in CIN1 and CIN2, respectively). Positive E4 staining was observed in 32.1% of CIN3 lesions, but this was mostly focal expression (25% focal, 7.1% extensive). Figure 2 shows examples of a CIN1 and CIN2 lesion with extensive E4 staining pattern and a CIN3 lesion with focal E4 expression.

a CIN1 lesion (ID45) with extensive E4 staining (score 2). Corresponding Ki-67 and p16 stainings showed Ki-67 positivity staining up to the lower one-third of the epithelium (score 1) and patchy p16 staining (score 0). Hypermethylation was found for three methylation markers. b CIN2 lesion (ID67) with extensive E4 staining (score 2). Corresponding Ki-67 and p16 stainings showed increased Ki-67 staining up to the lower two-third of the epithelium (score 2) and diffuse p16 staining up to the lower one-third (score 1) of the epithelium. Hypermethylation was found for three methylation markers. c CIN 3 lesion (ID90) with focal E4 staining (score 1). Corresponding Ki-67 and p16 stainings showed full thickness Ki-67 staining of the epithelium (score 3) and full thickness p16 staining of the epithelium (score 3). Hypermethylation was found for 3 methylation markers. ID numbers correspond with the ID numbers of Fig. 3.

Ki-67 and p16ink4a expression was compared between biopsies with productive (focal (score 1) or extensive E4 staining (score 2), E4 positive), and nonproductive (no E4 staining (score 0), E4 negative), characteristics (Table 2). E4 positive CIN1 lesions had higher Ki-67 and p16ink4a scores compared with E4 negative CIN1 lesions (p values < 0.001 and 0.006 for Ki-67 and p16ink4a, respectively). No significant differences in Ki-67 and p16ink4a scores were observed between E4 negative and E4 positive CIN2 or CIN3 lesions (p values > 0.1).

Correlation immunohistochemical findings in cervical biopsies with methylation levels in cervical scrapes

The expression patterns of E4, Ki-67, and p16ink4a in cervical biopsies and methylation of FAM19A4, miR124-2, ASCL1, and LHX8 in the corresponding cervical scrapes are shown in Fig. 3. This figure illustrates not only the increase in Ki-67 and p16ink4a expression and methylation levels with increasing CIN grade, but also the heterogeneity in CIN lesions. Figure 4 shows the distribution of methylation levels of all genes evaluated in E4 negative and E4 positive biopsies, stratified into low (0–3) and high (4+) cumulative Ki-67/p16ink4a immunoscores. E4 positive biopsies with low Ki-67/p16ink4a immunoscores had significantly higher methylation levels compared with E4 negative biopsies with low Ki-67/p16ink4a immunoscores. Methylation levels in cervical scrapes corresponding to biopsies with high Ki-67/p16ink4a immunoscores did not differ between E4 positive and E4 negative biopsies. When stratified by reference standard (i.e., CIN1 or less, CIN2, and CIN3), similar results were obtained: E4 positive biopsies with CIN1 or less had significantly higher methylation levels compared with E4 negative biopsies with CIN1, but no differences in methylation levels were observed between E4 positive and E4 negative biopsies with CIN2 or CIN3 (see Supplementary Fig. 1).

This figure shows the immunohistochemical scores for E4 (0–2), Ki-67 (0–3), and p16ink4a (0–3) in cervical biopsies across histological subgroups based on the reference standard, and methylation levels (ΔΔCt ratios) in corresponding cervical scrapes. In each subgroup, samples are consecutively ordered low-high based on their E4, Ki-67, p16ink4a, and methylation scores. The colors refer to the extent of immunohistochemical staining and hypermethylation, as indicated in the Legend. Methylation levels were categorized into ≤25th percentile, >25th ≤ 50 percentile, >50th ≤ 75 percentile, and >75th percentile; percentiles were calculated from all evaluated cervical scrapes. Each column within a subgroup represents one case: 6 no dysplasia, 45 CIN1, 23 CIN2, 18 CIN3. HPV human papillomavirus, CIN cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, MM methylation markers. *Positivity for either FAM19A4 and/or miR124-2 was caunted as one marker as this is a clinically validated kit.

Discussion

In this study we described IHC staining patterns of Ki-67, p16ink4a, and HPV E4 in a series of cervical biopsies from HIV and HPV co-infected women from a South African screening cohort. The extent of epithelial expression of Ki-67 and p16ink4a, markers of a transforming HPV infection, increased with severity of cervical dysplasia, while E4 expression, a marker for productive infection, increased from CIN1 (37%) to CIN2 (71%) and decreased in CIN3 (32%, mostly focal). This abundant expression of E4 in this population indicates more production of infectious virions and a high proportion of productive HPV infections compared with CIN lesions from HIV-uninfected women [26, 27]. Productive CIN1 lesions (i.e., E4 positive) showed moderately increased expression of Ki-67 and p16ink4a, and increased methylation of host cell genes in the corresponding cervical scrape compared with nonproductive (i.e., E4 negative) CIN1 lesions. Together these findings illustrate the heterogeneity of CIN lesions in women living with HIV and show that these cervical lesions can exhibit productive and transforming characteristics simultaneously.

This simultaneous expression of markers indicative for productive and transforming infections may be the result of the immunocompromised status of women living with HIV, resulting in decreased HPV clearance, increased susceptibility for HPV-induced cellular transformation, and faster progression to cancer. This lack of immune control may also lead to increased expression of HPV E6 and E7 oncogenes, reflected by the presence of Ki-67, p16ink4a, and hypermethylation of host cell genes, and cause cellular transformation. Viral oncogene expression may be further aggravated by a molecular interaction between HIV and HPV. It has been suggested that the HIV protein tat contributes to HPV-induced carcinogenesis by stimulating the expression of E6 and E7 [33, 34] and by increasing methylation of host cell genes through upregulation of DNA methyltransferase expression [35]. Alternatively, the E4 negative CIN1 lesions may not be representative of the high-risk HPV infection detected in the corresponding cervical scrape due to a sampling error in taking the cervical biopsies. Unfortunately, due to insufficient quality of the DNA isolated from the cervical biopsies, we were unable to detect HPV directly in the CIN lesion. Other explanations for the lack of E4 expression in CIN1 lesions include tangential sectioning and tissue damage during sample processing, causing loss of the upper epithelial layer expressing E4. Furthermore, some E4 negative CIN1 lesions may represent regressive lesions [36]. Future studies to investigate the expression of HPV E4 in CIN1 lesions are indicated. A schematic representation of the expression of the IHC and methylation markers in women living with HIV and previous findings in HIV-uninfected women [27] is given in Fig. 5.

Productive (E4 expression) and transforming (Ki-67/p16ink4a expression and hypermethylation) characteristics show greater overlap in HIV-infected women compared with HIV-uninfected women [27], suggesting that the process of transformation starts earlier after an HPV infection in HIV-infected women compared with HIV-uninfected women, which could be consistent with a faster progression of CIN lesions to cancer in HIV-infected women. Methylation levels of host cell genes are higher in HIV-infected women without dysplasia or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 1 compared with HIV-uninfected women. More E4 positivity is present in HIV-infected compared with HIV-uninfected women. CIN cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, HIV human immunodeficiciency virus, HPV human papillomavirus, IS immunoscore, MM methylation markers.

To our knowledge, this is the first study describing the expression of E4 in cervical biopsies from women living with HIV. In a similar series from HIV-uninfected women, Leeman et al. describe expression of p16ink4a and E4 in cervical biopsies and methylation of FAM19A4 and miR124-2 genes in corresponding cervical scrapes [37]. Although E4 was less expressed in their series, E4 positivity was highest in CIN1 and CIN2 lesions and was associated with the presence of p16ink4a positivity up to two-thirds of the epithelium. This is consistent with our observation that E4 positive CIN1 lesions have higher Ki-67 and p16ink4a scores compared with E4 negative CIN1 lesions and may be explained by the E7-driven epithelial proliferation above the basal layer, which is necessary for viral reproduction [38].

In line with previous reports on the value of p16ink4a and Ki-67 immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of CIN [8, 9, 16, 20, 39], our study suggests that these markers could be used to optimize identification of CIN lesions in women living with HIV requiring treatment. However, the question remains whether there is a role for any of these IHC markers beyond the objective identification of CIN. Indeed, the prognostic value of Ki-67 and p16ink4a in the clinical behavior of CIN2 and CIN3 lesions has shown to be limited [40,41,42] and the clinical value of E4 remains to be determined. Host cell methylation on the other hand, is a promising biomarker as increased methylation of host cell genes is associated with more chromosomal aberrations necessary for progression to cervical cancer [17,18,19]. In fact, the prognostic value of methylation analysis was recently demonstrated by Louvanto et al. showing that methylation of cellular gene EPB41L3 is associated with progression of untreated CIN2 in HIV-uninfected women [43]. The same marker was also evaluated in African women living with HIV showing increased methylation in women with progressive lesions [44].

Together these data support the notion that the presence of hypermethylation of host cell genes indicates an advanced transforming lesion with a high short-term progression risk, and therefore could be used to direct treatment decisions. In women living with HIV, high baseline methylation levels [24, 25] might illustrate their high cervical cancer progression risk compared with HIV-uninfected women. Clinical follow-up studies are now in progress to evaluate the prognostic value of methylation analysis in women living with HIV, and to show whether all women living with HIV with high methylation levels indeed require treatment of these lesions. In addition, further evaluation of genetic and epigenetic alterations associated with cervical cancer in women living with HIV is required to support our hypothesis that these lesions have an increased progression risk.

Strong points of our study are that we have thoroughly reviewed all cervical dysplastic features within HIV and HPV co-infected women and that a histological endpoint was available for all women screened, thereby creating the possibility to analyze the full spectrum of HPV-associated cervical disease. A limitation of this study is that the duration of HPV infection associated with the lesion cannot be estimated, as most women participating had never been screened before. Therefore, long-existing lesions may be present in this under-screened population and may provide an explanation for the high methylation levels found in our study.

Another limitation is that some biopsies may not represent the worst underlying lesion due to a sampling error in taking the biopsy. It should, however, be realized that excisional treatment of the transformation zone of women in this study was not only based on a CIN2+ finding in the cervical biopsy, but also directly on a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or worse (≥HSIL) cytology result [25]. This study algorithm results in a small group of women having ≤CIN1 on cervical biopsy with a CIN3 in their excision specimen, suggesting a possible sampling error (see Supplementary Table 2). Unfortunately, the excision specimens were not available for IHC evaluation. We accounted for this sampling error by repeating the analyses after exclusion of women with a CIN3+ diagnosis on their excision specimen that was not diagnosed in the biopsy. The same trend of higher methylation levels in cervical scrapes of women with E4 positive low-grade lesions compared with E4 negative low-grade lesions was observed, yet only significant for ASCL1.

Conclusion

In this series of cervical biopsies from HIV and HPV co-infected women, CIN lesions with both productive (E4 positivity) and transforming characteristics (increased Ki-67 and p16ink4a staining) were abundantly present. The presence of high methylation levels in scrapes of CIN lesions with IHC characteristics of productive and/or transforming infections in women living with HIV could suggest a rapid progression of CIN lesions towards cancer in these women.

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424.

zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342–50.

Chaturvedi AK, Madeleine MM, Biggar RJ, Engels EA. Risk of human papillomavirus-associated cancers among persons with AIDS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1120–30.

De Vuyst H, Lillo F, Broutet N, Smith JS. HIV, human papillomavirus, and cervical neoplasia and cancer in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17:545–54.

Sun XW, Kuhn L, Ellerbrock TV, Chiasson MA, Bush TJ, Wright TC Jr. Human papillomavirus infection in women infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1343–9.

Dryden-Peterson S, Bvochora-Nsingo M, Suneja G, Efstathiou JA, Grover S, Chiyapo S, et al. HIV infection and survival among women with cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3749–57.

Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in South Africa. Summary Report 17 June 2019.

Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, Heller DS, Henry MR, Luff RD, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. J Low Genit Trac Dis. 2012;16:205–42.

Herrington CS. The terminology of pre-invasive cervical lesions in the UK cervical screening programme. Cytopathology. 2015;26:346–50.

Stoler MH, Schiffman M, Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance-Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion Triage Study G. Interobserver reproducibility of cervical cytologic and histologic interpretations: realistic estimates from the ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study. JAMA. 2001;285:1500–5.

Ostor AG. Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:186–92.

McCredie MRE, Sharples KJ, Paul C, Baranyai J, Medley G, Jones RW, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:425–34.

Bierkens M, Wilting SM, van Wieringen WN, van Kemenade FJ, Bleeker MC, Jordanova ES, et al. Chromosomal profiles of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia relate to duration of preceding high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:E579–85.

Steenbergen RD, Snijders PJ, Heideman DA, Meijer CJ. Clinical implications of (epi)genetic changes in HPV-induced cervical precancerous lesions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:395–405.

Kyrgiou M, Athanasiou A, Paraskevaidi M, Mitra A, Kalliala I, Martin-Hirsch P, et al. Adverse obstetric outcomes after local treatment for cervical preinvasive and early invasive disease according to cone depth: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;354:i3633.

van Zummeren M, Leeman A, Kremer WW, Bleeker MCG, Jenkins D, van de Sandt M, et al. Three-tiered score for Ki-67 and p16(ink4a) improves accuracy and reproducibility of grading CIN lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2018;71:981–8.

Bierkens M, Hesselink AT, Meijer CJ, Heideman DA, Wisman GB, van der Zee AG, et al. CADM1 and MAL promoter methylation levels in hrHPV-positive cervical scrapes increase proportional to degree and duration of underlying cervical disease. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1293–9.

Verlaat W, Snijders PJF, Novianti PW, Wilting SM, De Strooper LMA, Trooskens G, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling reveals methylation markers associated with 3q Gain for detection of cervical precancer and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:3813–22.

De Strooper LM, Meijer CJ, Berkhof J, Hesselink AT, Snijders PJ, Steenbergen RD, et al. Methylation analysis of the FAM19A4 gene in cervical scrapes is highly efficient in detecting cervical carcinomas and advanced CIN2/3 lesions. Cancer Prev Res (Philos). 2014;7:1251–7.

Nicol AF, Golub JE, e Silva JR, Cunha CB, Amaro-Filho SM, Oliveira NS, et al. An evaluation of p16(INK4a) expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia specimens, including women with HIV-1. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:571–7.

Queiroz C, Silva TC, Alves VA, Villa LL, Costa MC, Travassos AG, et al. Comparative study of the expression of cellular cycle proteins in cervical intraepithelial lesions. Pathol Res Pr. 2006;202:731–7.

Spinillo A, Zara F, Zappatore R, Cesari S, Bergante C, Morbini P. Apoptosis-related proteins and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive women. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:500–5.

Kremer WW, van Zummeren M, Heideman DAM, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Snijders PJF, Steenbergen RDM, et al. HPV16-related cervical cancers and precancers have increased levels of host cell DNA methylation in women living with HIV. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:e3297.

Kremer WW, Van Zummeren M, Novianti PW, Richter KL, Verlaat W, Snijders PJ, et al. Detection of hypermethylated genes as markers for cervical screening in women living with HIV. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21:e25165.

Van Zummeren M, Kremer WW, Van Aardt MC, Breytenbach E, Richter KL, Rozendaal L, et al. Selection of women at risk for cervical cancer in an HIV-infected South African population. AIDS. 2017;31:1945–53.

van Baars R, Griffin H, Wu Z, Soneji YJ, van de Sandt M, Arora R, et al. Investigating diagnostic problems of CIN1 and CIN2 associated with high-risk HPV by combining the novel molecular biomarker PanHPVE4 With P16INK4a. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1518–28.

Zummeren MV, Kremer WW, Leeman A, Bleeker MCG, Jenkins D, Sandt MV, et al. HPV E4 expression and DNA hypermethylation of CADM1, MAL, and miR124-2 genes in cervical cancer and precursor lesions. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1842–50.

Wright TC, Ronnett BM, Kurman RJ. Precancerous Lesions of the Cervix, In: Kurman RJ, Hedrick Ellenson L, Ronnett BM, editors. Blaustein’s pathology of the female genital tract. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 239–313.

Kremer WW, van Zummeren M, Breytenbach E, Richter KL, Steenbergen RDM, Meijer C, et al. The use of molecular markers for cervical screening of women living with HIV in South Africa. AIDS. 2019;33:2035–42.

Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–8.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

van Baars R, van der Marel J, Snijders PJ, Rodriquez-Manfredi A, ter Harmsel B, van den Munckhof HA, et al. CADM1 and MAL methylation status in cervical scrapes is representative of the most severe underlying lesion in women with multiple cervical biopsies. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:463–71.

Tornesello ML, Buonaguro FM, Beth-Giraldo E, Giraldo G. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 tat gene enhances human papillomavirus early gene expression. Intervirology. 1993;36:57–64.

Barillari G, Palladino C, Bacigalupo I, Leone P, Falchi M, Ensoli B. Entrance of the Tat protein of HIV-1 into human uterine cervical carcinoma cells causes upregulation of HPV-E6 expression and a decrease in p53 protein levels. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:2389–94.

Youngblood B, Reich NO. The early expressed HIV-1 genes regulate DNMT1 expression. Epigenetics. 2008;3:149–56.

Griffin H, Soneji Y, Van Baars R, Arora R, Jenkins D, van de Sandt M, et al. Stratification of HPV-induced cervical pathology using the virally encoded molecular marker E4 in combination with p16 or MCM. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:977–93.

Leeman A, Jenkins D, del Pino M, Ordi J, Torné A, Doorbar J, et al. Expression of p16 and HPV E4 on biopsy samples and methylation of FAM19A4 and miR124‐2 on cervical cytology samples in the classification of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions. Cancer Med. 2020. [Epub ahead of print].

Doorbar J. The papillomavirus life cycle. J Clin Virol. 2005;32(Suppl 1):S7–15.

Castle PE, Adcock R, Cuzick J, Wentzensen N, Torrez-Martinez NE, Torres SM, et al. Relationships of p16 immunohistochemistry and other biomarkers with diagnoses of cervical abnormalities: implications for LAST terminology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019. [Epub ahead of print].

Guedes AC, Brenna SM, Coelho SA, Martinez EZ, Syrjanen KJ, Zeferino LC. p16(INK4a) Expression does not predict the outcome of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:1099–103.

Omori M, Hashi A, Nakazawa K, Yuminamochi T, Yamane T, Hirata S, et al. Estimation of prognoses for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 by p16INK4a immunoexpression and high-risk HPV in situ hybridization signal types. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:208–17.

Ovestad IT, Gudlaugsson E, Skaland I, Malpica A, Munk AC, Janssen EA, et al. The impact of epithelial biomarkers, local immune response and human papillomavirus genotype in the regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2-3. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:303–7.

Louvanto K, Aro K, Nedjai B, Butzow R, Jakobsson M, Kalliala I, et al. Methylation in predicting progression of untreated high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin Infect Dis. 2019. [Epub ahead of print].

Kelly HA, Chikandiwa A, Warman R, Segondy M, Sawadogo B, Vasiljevic N, et al. Associations of human gene EPB41L3 DNA methylation and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in women living with HIV-1 in Africa. AIDS. 2018;32:2227–36.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all the women participating in the described study. We are grateful for the active cooperation of the teams of the outpatient department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of the Steve Biko Academic Hospital and the HIV clinic at the Tshwane District Hospital. CJLMM was in part supported by European Research Council; Grant number: ERC-AdG-2012_322986_MASSCARE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

CJLMM is a minority shareholder of Self-screen B.V., a spin-off company of VUmc which develops, manufactures and licenses the high-risk HPV assay and methylation marker assays for cervical cancer screening and holds patents on these tests. CJLMM is part-time CEO of Self-Screen B.V., has a very small number of shares of Qiagen and MDXHealth, has received speakers’ fees from GSK, Qiagen, and SPMSD/Merck, and served occasionally on the scientific advisory boards (expert meeting) of these companies. WWK, FJV, MZ, MCGB, LR, JD and GD declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41379_2020_528_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary information is available at Modern Pathology’s website.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kremer, W.W., Vink, F.J., van Zummeren, M. et al. Characterization of cervical biopsies of women with HIV and HPV co-infection using p16ink4a, ki-67 and HPV E4 immunohistochemistry and DNA methylation. Mod Pathol 33, 1968–1978 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0528-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0528-x

This article is cited by

-

A randomised controlled non-inferiority trial to compare the efficacy of ‘HPV screen, triage and treat’ with ‘HPV screen and treat’ approach for cervical cancer prevention among women living with HIV

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Promoter hypermethylation analysis of host genes in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancers on histological cervical specimens

BMC Cancer (2023)