Abstract

Background

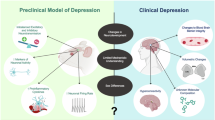

In animal models, the habenula has been identified as a key structure involved in mood disorders (MDs). Thanks to recent technological advancements, a burgeoning body of work has also investigated the habenula in the context of human MDs.

Objective

This systematic review aims to synthesize findings from human studies concerning the habenula and its relationship with MDs. The review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. The literature search yielded 93 articles, of which 50 articles were included in the review.

Results

We found that the evidence for baseline habenular hyperactivity in human depression is mixed. Although the finding of baseline habenular hyperactivity is widely replicated in animal models of depression, the available evidence is not sufficient to either conclude the presence or the absence of this hyperactivity in human depression. As for findings from resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) studies, they were mainly inconsistent across studies. Nevertheless, a notable observation is that alterations in connectivity between the habenula and regions of the default mode network (DMN) were overrepresented in the results, suggesting that connections between the habenula and DMN regions may play a role in MDs. Lastly, we found no evidence indicating that MDs are linked to changes in habenular volume.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The habenula is a small bilateral nucleus located at the dorsal end of the diencephalon. In mammals, it comprises two distinct nuclear complexes: the lateral habenula (LHb) and the medial habenula (MHb). These two subregions greatly differ in their neuroanatomical connectivity [1] and gene expression profiles [2]. They are thus believed to be functionally distinct [3]. While there exists a large body of animal research devoted to studying the LHb, relatively little is known about the MHb [2]. Over the past 2 decades, the LHb has garnered growing attention [4], largely for its involvement in dopaminergic reward circuitry and its proposed role in psychiatric conditions such as addiction and mood disorders (MDs) [5]. The idea that the LHb plays a role in MDs arose from two major streams of research in animal models.

One central line of work hinted at an involvement of the LHb in the etiology of MDs by bringing attention to its role in negative reward processing. This function of the LHb was first suggested by a 2003 fMRI study in humans [6], and further supported in 2007 by the work of Matsumoto and Hikosaka in nonhuman primates [7]. In the latter study, habenular neuron activity was recorded, revealing that the LHb is activated by cues predicting the absence of reward and inhibited by cues predicting reward. These findings suggested that the LHb encodes negative reward prediction errors (RPEs). This idea was later bolstered by the results of a follow-up experiment from the same group, revealing activation of the LHb in response to punishment and inhibition following reward [8]. Subsequent work in fish and rodents yielded analogous findings [9, 10], indicating that the LHb’s role in the coding of negative RPEs is evolutionarily ancient and widely conserved across species. Owing to its function in negative reward processing, the LHb is well-positioned to contribute to mood disorders. Indeed, reward processing is altered in major depressive disorder (MDD) [11]. More precisely, not only is reward learning impaired, but neural processing of RPEs is also altered [12, 13]. Thus, because the LHb is involved in the processing of RPEs, it stands out as a structure that, when dysfunctional, may contribute to reward-related deficits observed in depression.

More direct evidence for the involvement of the LHb in mood disorders was provided by a second body of research investigating the LHb in animal models of depression(for reviews see [5, 14, 15]). Overall, findings from this literature imply that elevated baseline activity of the LHb, which has been observed in multiple animal models of depression (e.g., [16,17,18]), plays an instrumental role in depression. Baseline hyperactivity of the LHb in depression was first discovered in the seminal work of Caldecott-Hazard et al. [16], who showed that glucose metabolism in the LHb was elevated across three different rodent models of depression. This elevation was found bilaterally. The LHb was the only region across the brain to be consistently hyperactive in the three models. More specifically, it is the increase in LHb burst firing that appears to be depressogenic [19]. It is thought that the heightened bursting activity of the LHb results in a more pronounced inhibition of monoaminergic nuclei, thereby promoting depression [20]. Indeed, via direct and indirect efferent pathways, the LHb has the unique capacity to inhibit both serotonin release via the raphe nuclei [21] and dopamine release via the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the substantia nigra [22].

Various sources of evidence underscore LHb hyperactivity as a key mechanism in the etiology of depression. Proulx et al. [23] showed that optogenetic activation of a projection from the LHb to the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg) is sufficient to induce depressive-like symptoms in rats. In contrast, pharmacological inhibition of the LHb was shown to exert antidepressant effects in a rat model of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) [24]. Moreover, lesions of the LHb reduce depressive-like behavior if performed once animals have been exposed to chronic mild stress [25] and prevent the development of depressive-like symptoms if performed before exposing animals to repeated inescapable electric shocks [26]. Lastly, there is evidence that the rapid antidepressant effect of ketamine is elicited by reversing the increased burst firing of LHb neurons [27]. In essence, the above literature highlights LHb hyperactivity as a core neural mechanism driving depression.

Historically, progress in understanding the functions of the human habenula has been hampered by its small size and deep subcortical location, which makes precise in vivo imaging challenging. Indeed, imaging the habenula is challenging in many ways. First, its small size makes it highly susceptible to partial volume effects, where the signal from the habenula may be contaminated by signals from adjacent thalamic regions. Additionally, its proximity to the CSF-filled third ventricle increases the habenula’s vulnerability to cardiorespiratory physiological noise [28, 29]. Furthermore, the habenula is difficult to delineate due to its low anatomical MRI contrast with neighboring structures [30, 31] and conventional normalization algorithms struggle to align it accurately [32]. Despite these challenges, studying the habenula has become more feasible over the past decade due to significant advancements in both structural and functional imaging techniques, including the development of myelin-sensitive imaging and the advent of ultra-high-field (UHF) MRI. Myelin-sensitive imaging facilitates habenula delineation by increasing its contrast relative to the adjacent thalamus, while UHF MRI provides improved resolution, as well as superior signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) [28, 33]. Thanks to these technical advancements, there is now a burgeoning field investigating the human habenula both in healthy individuals and in relation to MDs, particularly depression. In healthy individuals, numerous findings have aligned with key results from animal studies. For instance, animal tract-tracing studies have demonstrated anatomical connections between the habenula and several key brain regions, including the VTA [1, 34], median raphe nuclei (MRN) [1, 34], dorsal raphe nuclei (DRN) [1, 34], and periaqueductal gray (PAG) [34]. Correspondingly, human functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have revealed resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) between the habenula and these same regions with quite good consistency [35,36,37,38], even though there are also some inconsistencies. Although functional connectivity cannot demonstrate anatomical connectivity, these patterns are nevertheless consistent with animal findings. Similarly, as discussed above, evidence from primates indicates that the LHb has a role in the coding of negative RPEs, and results from human studies are consistent with this notion. Indeed, fMRI studies have shown that the habenula is activated by the reception of negative feedback [39], by punishment [40, 41], by a cue predicting an aversive stimulus [42], and by the omission of an expected reward [43].

Multiple reviews about the habenula and its role in MDs have been published recently (e.g., [15, 20, 44,45,46]). However, these reviews focused on animal studies. To our knowledge, human studies have not been reviewed yet. As animal findings may not directly apply to humans, a review of human studies on the habenula and its relationship with MDs is greatly needed. Therefore, this systematic review aims to synthesize findings from human studies concerning the habenula and its relationship with MDs. In the paper, when referring to animal studies, we will differentiate between the LHb and the MHb. Because of the small size of the habenula, in vivo human studies do not usually differentiate between these two nuclei and instead study the habenula as a whole [33]. Thus, when discussing human studies, we will refer to the habenula altogether without distinguishing the LHb from the MHb.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [47] (see Supplementary Information for the PRISMA checklist). The methodological quality of the studies was assessed with the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies [48]. This review does not have a registered protocol.

An initial literature search was conducted using PubMed in April 2023. The search was later updated in January 2024. Inclusion criteria were a) human sample; b) structural or functional brain measurement of the habenula. Exclusion criteria were a) published in a language other than English; c) articles reporting results from deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the habenula without results pertaining to habenular structure or function; c) review papers; d) preprints. Lastly, because this review pertains to MDs, papers studying suicide or bipolar disorder (BD) were included, while those concerning post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were excluded, as PTSD is rather classified as an anxiety disorder [49]. Detailed information on the search strategy, study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Results

Description of studies

The search yielded 93 articles, of which 58 were retained for full-text screening. Moreover, one article was identified through citation searching. In total, 50 articles were included in the review (Fig. 1 [50]). These 50 articles comprised a total of 53 individual samples. Sample sizes varied between one and 423. There were 21 articles wherein at least one group had a sample size of 20 or less. Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. Papers were published between 1999 and 2024 (Fig. 2). The majority of the samples (64%) were collected either in China (20 samples) or in the United States (14 samples) (Fig. 2). According to our assessment of methodological quality, out of the 53 samples included in our review, six were classified as having good quality, 38 as fair, and nine as poor (for details, see Supplementary Information). The articles included in the review can be grouped into three distinct classes. One category encompasses articles that reported results about the activity of the habenula in the context of MDs (n = 12). By activity, we refer to any direct or indirect measure aiming at quantifying neuronal activity. We chose to group these studies because they are all relevant to the matter of habenular hyperactivity in depression. Another category comprises the papers that studied the connectivity of the habenula during resting-state fMRI in patients with MDs (n = 24), while the last category includes papers that presented structural findings (n = 19). Because some studies were included in more than one category [40, 51,52,53,54], the sum of studies in each category exceeds the total number of studies included in the review.

Activation studies

This section will synthesize findings from studies examining the activity of the habenula during a task or at rest. A total of twelve studies fit into this category (see Table S1). In 10 studies, the habenula was a region-of-interest (ROI), while in two others [55, 56] the habenula came up as a cluster in whole-brain analyses. Among the 10 studies that used the habenula as an ROI, seven separated the left from the right habenula for the analyses [40, 53, 57,58,59,60,61], while three combined both habenulas [62,63,64]. Six studies used fMRI [40, 53, 56, 58, 59, 63], two used positron emission tomography (PET) scan [55, 57], and four employed intracerebral electrodes to record local field potentials (LFPs) within the habenula [60,61,62, 64]. Four studies reported resting-state results [57, 59, 61, 64], while six studies reported task-related results [40, 55, 56, 58, 62, 63]. Two other studies reported both resting-state and task-related results [53, 60].

Comparison of resting-state habenular activity between MDD patients and HCs

The study conducted by Lawson et al. [53] is the only study that directly compared resting-state habenular activity between MDD patients and healthy controls (HCs). In this study, both MDD patients and HCs underwent a resting-state fMRI session. In order to estimate the habenular activity, authors used arterial spin labeling (ASL), an MRI technique allowing to quantify cerebral blood flow (CBF) [65]. No between-group difference was found in habenular CBF.

Induction and treatment of depression

Three studies provided data relevant to the matter of baseline habenular hyperactivity in human depression by either administering a treatment for depression (one study) or by employing a pharmacological procedure aimed at inducing a depressive-like state in participants (two studies). Carlson et al. [57] reported findings consistent with the idea that a treatment for depression can reduce baseline habenular activity. They observed that in a sample of 20 patients receiving ketamine treatment for TRD, glucose metabolism in a region encompassing the right habenula decreased following ketamine injections. However, there was no significant difference for the left habenula. The two studies seeking to induce a state resembling depression did so by exposing their participants to acute tryptophan depletion (ATD). ATD is a method aimed at inducing a transient depressive-like state that consists of lowering brain levels of tryptophan, the precursor of serotonin. This method is particularly effective in inducing depressive symptoms in people already vulnerable to depression [66]. Accordingly, the two studies that employed ATD enrolled participants currently in remission from MDD—participants assumed to be susceptible to depression. The first study used PET scan to measure neural activity during cognitive tasks under ATD [55]. Strikingly, across the whole brain, a voxel in a region encompassing the habenula was where the activity was the most strongly negatively correlated with tryptophan levels. In other words, lower levels of tryptophan were associated with more activity in the habenula. Moreover, following ATD, a voxel in a region encompassing the habenula was where activity was most strongly correlated with depressive symptoms across the brain, consistent with the baseline hyperactivity of the habenula present in animal models of depression. In the second study, participants underwent a resting-state fMRI session following the administration of ATD. Patients with remitted major depressive disorder (rMDD) showed significantly higher left habenular blood flow when compared to HCs [59]. However, there was no significant difference for the right habenula.

Intracranial recording

Rather than employing ex vivo methods such as fMRI and PET scan, four studies have used intracerebral recordings to study the relationship between habenular activity and MDs. These studies measured LFPs within the habenula. The LFP is the electrical potential measured in the extracellular environment surrounding neurons [67]. When measuring LFPs within habenula, the assumption is that the signal measured reflects neural activity from habenular neurons (but see [68, 69]).

Sonkusare et al. [60] used the aperiodic component, which reflects non-oscillatory brain activity. It is thought that the greater the aperiodic component, the greater the excitation-inhibition ratio [70]. Therefore, in this study, the aperiodic component was used as a proxy for the excitation-inhibition ratio of the habenula. Their results revealed a high correlation (r = 0.88) between the aperiodic component of the left habenula and depression scores in a sample of six TRD patients. This positive correlation between the aperiodic component and depressive symptoms could indicate that higher excitation within the left habenula is associated with higher levels of depression, in line with the increased burst firing of the LHb described in rodent models of depression. It is worth noting, however, that four out of their six patients had a diagnosis of BD, which may affect the habenula in a different way than unipolar depression. Furthermore, no significant correlation was found for the right habenula. Another paper investigated the association between the power spectral density (PSD) of oscillations recorded in the habenula and depressive symptoms. Lower PSD of habenular oscillations ranging from theta to gamma frequency bands (except for low betas) were generally associated with heightened depression in TRD patients [61]. This was the case for both the left and the right habenula. PSD of habenular oscillations does not directly inform us about activity in the habenula. However, lower PSD of habenular oscillations suggests lower neuronal synchronization within the LHb. Because burst firing is thought to enhance the synchronization of neural networks [71, 72], one possibility is that lower PSD reflects lower burst firing. These results appear consistent with the results of a case report where one patient underwent DBS for TRD. In this study [64], the PSD in the delta, theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands increased along with the clinical improvements of this patient over time. However, results from these two studies conflict with a study conducted in a rodent model of depression. In this study, LFPs in the LHb were measured before and after a DBS protocol aimed at treating depression. PSD was lower after the DBS from theta to low gamma frequencies [73]. Because DBS reduced depressive symptoms, this suggests that lower PSD in these frequencies was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms. Lastly, another study reported that, in response to negative emotional stimuli, neither alpha nor theta frequencies recorded in the habenula correlated with depression scores in patients with psychiatric disorders [62]. On the contrary, one study in rodents found that depression was associated with higher theta-band synchronization [27]. However, an important distinction between these studies may explain the apparent inconsistency. Indeed, in the human study, LFPs were measured in response to negative emotional stimuli, which was not the case in the animal study.

Task-based fMRI

Five task-based fMRI studies reported results about the habenula and its relationship with MDs. Three of these studies investigated whether there is a difference in habenular activation between MDD patients and HCs when processing stimuli with negative motivational value. One study [40] found that MDD patients exhibited a trend toward heightened activation in the right habenula when processing punishment. In contrast, the same study also found a trend for reduced activity in the left habenula. Another study observed a reduction in activity in the left habenula of MDD patients in response to losses in a task involving monetary rewards and losses [58]. Lastly, one study found that the activity of the whole habenula when processing stimuli with negative motivational value was reduced in MDD patients [53]. Additionally, Kumar et al. [63] reported no group difference in negative RPE signals in the habenula between MDD and HCs [63]. The fifth study found that the activity of the habenula during the processing of loss prediction error was negatively correlated with anhedonia in MDD [56].

Connectivity studies

This section will synthesize findings from studies that used fMRI to examine resting-state connectivity of the habenula in the context of MDs. There were 24 such studies (see Table S2). In all studies, the habenula was defined a priori as an ROI. Among the 24 studies, 19 separated the left from the right habenula seeds for the analyses, while five combined both seeds. Twenty-two papers were directly interested in the habenula and its relationship with MDs, while two others investigated the habenula in other conditions: chronic low-back pain [74] and anorexia [75]. These two studies nevertheless reported correlations between depressive symptoms and the resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) of the habenula. Of the 22 studies directly interested in MDs, 16 conducted analyses comparing the connectivity of the habenula between groups (e.g., MDD versus HC), and six investigated how the connectivity of the habenula changes in response to depression treatments: ketamine injections [76,77,78], bright light therapy [79], DBS [51], and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) [80]. From these same 22 studies, 15 conducted a seed-to-whole-brain analysis with the habenula as a seed. One study performed both ROI-to-ROI and seed-to-whole-brain analyses [76]. Another one used a seed-to-voxel analysis where voxels within specific ROIs were considered in addition to ROI-to-ROI analyses [81]. Three studies exclusively performed ROI-to-ROI analyses [52, 82, 83]. Lastly, two studies opted for network analysis [84, 85], which is a framework that envisions the brain as an intricate network. This network can be illustrated graphically by nodes and edges, with the latter symbolizing the relationships between the nodes [86].

Among connectivity studies (i.e., comparing habenular connectivity between groups with and without MDs or before and after a depression treatment), reports of findings about regions of the default mode network (DMN) stood out as particularly common (Fig. 3). The DMN regions reported in at least two studies were the precuneus (5 studies; 10 pairings), the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (when combining results for its ventral and dorsal parts) (5 studies; 6 pairings), the middle temporal gyrus (MTG) (4 studies; 5 pairings), the parahippocampal gyrus (PHG) (3 studies; 3 pairings), and the posterior cingulate gyrus (PCC) (2 studies; 2 pairings). Among brain regions outside the DMN (Fig. 3), the regions reported in at least two studies were the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (5 studies; 6 pairings), the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) (5 studies; 5 pairings), the anterior/middle cingulate cortex (5 studies; 5 pairings), the superior temporal gyrus (STG) (5 studies; 5 pairings), the precentral gyrus (4 studies; 4 pairings), the postcentral gyrus (4 studies; 4 pairings), the cerebellum (4 studies; 7 pairings), the inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) (3 studies; 4 pairings), the locus coeruleus (3 studies; 3 pairings), the occipital gyrus (2 studies; 3 pairings), the supplementary motor area (2 studies; 2 pairings), the amygdala (2 studies; 2 pairings), the insula (2 studies; 2 pairings), and the calcarine/lingual gyrus (2 studies; 2 pairings).

Findings related to structures reported in more than one study are presented in Table 2 (DMN regions) and Table 3 (other regions). Overall, in most cases, no clear pattern emerged from the findings. Indeed, among the studies that were similar enough to be directly compared, the vast majority of findings were (1) not reported in more than one study or (2) reported in more than one study but contradicted by at least one other study. For a narrative description of the results, see the Supplementary Information. The only finding that was reported in at least three studies was that the RSFC between the left mPFC and the habenula was higher in depression [35, 54, 87].

Structural studies

Overall, 19 studies reported structural results. In 16 studies, the habenula was an ROI, while in three others [88,89,90] the habenula came up as a cluster in whole-brain analyses. Among the 16 studies using the habenula as an ROI, 12 separated the left from the right habenula for the analyses, while four combined both habenulas [51, 91,92,93]. Fourteen studies presented volumetric results and three studies used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) [52, 93, 94]. One study used MRI-based quantitative susceptibility mapping, a method used to estimate brain iron deposition [90]. One last study measured serotonin transporter (SERT) availability across the brain to predict response to antidepressants [89].

Volumetric studies

In total, 11 studies reported total habenular volume exclusively (see Table S3). One study reported total habenular volume in addition to white and gray matter volumes [91]. Two studies focused on gray matter volume but did not report whole habenular volume [88]. Among all volumetric studies, seven compared the volume of the habenula between depressed patients and HCs. Five out of the seven studies found no significant difference in habenular volume between depressed patients and HCs [53, 54, 91, 95, 96]. One study observed a smaller volume of the right habenula in MDD patients [97], while another reported a larger bilateral habenular volume in MDD patients [40]. Another study, which measured habenular gray matter volume exclusively, found that TRD patients had a smaller habenular gray matter volume [88]. Savitz et al. [98] compared the habenular volume between HCs and patients with either medicated BD, unmedicated BD, unmedicated MDD, or unmedicated rMDD. They did not find any difference between MDD patients and controls. Their main finding was that unmedicated BD patients had a smaller habenular volume than HCs for both left and right habenulas. Another study used post-mortem data to compare the volume of the habenula between HCs and a group containing both MDD and BD patients. They found a smaller volume of the right MHb and right LHb in MDD/BD patients versus HCs [99]. Lastly, two studies compared BD patients and HCs. Both studies reported no difference in habenular volume between groups [92, 100]. Overall, despite some conflicting volumetric findings, it does not seem like habenular volume is consistently altered in MDs.

Structural connectivity studies

Three studies investigated habenular structural connectivity and its relationship with MDs. To do so, they used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), a technique used to map white matter tracts in the brain [101]. Cho et al. [94] investigated structural connectivity between the thalamus and the habenula in MDD patients and HCs. They observed that MDD patients had significantly more white matter tracts connecting the right habenula to the left mediodorsal thalamus. In depressed patients, a study utilizing DTI found that those who failed to respond to treatment had lower fractional anisotropy in the right habenular afferent fibers compared to treatment responders. This was interpreted as indicative of lower structural connectivity between the habenula and its upstream connections [52]. Lastly, another study found that higher fractional anisotropy between the habenula and the hypothalamus was related to lower depression scores [93]. Overall, due to the variety of research questions addressed, no clear pattern emerges from these studies.

Discussion

Is the habenula hyperactive in human depression?

Baseline hyperactivity of the LHb stands out as a central finding from animal models of depression [5]. Activation studies are the most pertinent to ascertain its existence in human depression. Four reviewed studies are particularly relevant to the matter of habenular hyperactivity in depression.

The study conducted by Lawson et al. [53] was the best designed to determine whether the habenula is hyperactive in human depression. Using ASL, the researchers compared habenular CBF between actual MDD patients and HCs during resting-state. This study offers three key strengths regarding the investigation of habenular hyperactivity in depression. First, the design allows for a more direct comparison with findings from animal models, where the activity of the habenula has been compared between animals exhibiting depressive-like behaviors and controls (e.g., [16, 102]). Second, this study measured resting-state rather than task-related habenular activity. This also facilitates comparisons with the animal literature. Indeed, animal findings suggest that depression is associated with higher baseline activity in the habenula [103], but task-related habenular activity has not been compared between depressed animals and controls, to our knowledge. Third, the use of ASL, rather than the more commonly employed BOLD fMRI, is particularly well-suited to addressing the research question. ASL is an MRI technique measuring tissue perfusion (i.e., blood flow) using magnetically labeled arterial blood water protons as an endogenous tracer [104]. It is ideal for assessing baseline brain activity, as it allows for quantification in absolute units [105]. Indeed, ASL allows measurement of CBF, which is a measure of the amount of blood delivered to brain tissue at the capillary level, expressed in milliliters of blood per 100 grams of tissue per minute (ml/100 g/min). It reflects the rate of blood supply to a specific area of the brain over a set time period [105].In contrast, the physiological meaning of the BOLD signal is more ambiguous [106], as BOLD is measured in arbitrary units and reflects changes relative to a baseline, rather than absolute activity [107, 108]. Therefore, BOLD fMRI is less suitable for measuring baseline brain activity. Additionally, the BOLD signal is prone to low-frequency drifts unrelated to neural activity [109], while ASL is not affected by these drifts [110]. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that ASL-derived resting CBF measurements are highly stable across time, with consistency observed across intervals ranging from minutes to days [111,112,113]. Importantly, in contradiction with the habenular hyperactivity reported in animal studies (e.g., [16,17,18, 114]), Lawson et al. found no significant difference in habenular CBF between the groups [53]. However, ASL has an inherently low SNR [115], which, combined with the study’s relatively small sample size (23 MD and 22 HCs), may explain the non-significant findings. Additionally, this study employed a pulsed ASL (PASL) sequence, which has considerably lower SNR than the commonly recommended pseudo-continuous ASL (pCASL) sequence [116, 117].

Other approaches used to investigate the activity of the habenula aimed at either inducing a depressive-like state in participants or at relieving depression. Using PET scan, Carlson et al. [57] found evidence of reduced glucose metabolism following ketamine treatment in a region consistent with the location of the right habenula. In contrast, no significant difference was found for the left habenula [57]. However, the fact that ketamine reduces habenular glucose metabolism does not necessarily imply that the habenula is hyperactive in MDD patients. Moreover, the conclusions of this study should be interpreted with great caution, as the image resolution was quite low, with a voxel size (6 mm isotropic) considerably greater than the habenula itself. Therefore, these findings cannot speak specifically to the habenula, but rather to a region that encompasses, but is not limited to, the habenula. Findings from this study can nevertheless be interpreted as consistent with the theory of hyperactivity, although by no means do they constitute strong evidence. There are also two studies that sought to induce depressive-like symptoms in rMDD patients by exposing them to ATD [55, 59]. One study acquired ASL images to measure CBF [59], while the other used PET to assess glucose metabolism [55]. Taken together, these two studies were both coherent with the idea of habenular hyperactivity in depression. One caveat is that, as is typical of PET and ASL imaging, the resolution in both studies was low, suggesting that the signal attributed to the habenula may have been contaminated by signals from surrounding regions. Another important consideration is the uncertainty surrounding ATD as an adequate model of depression. Although ATD appears to negatively impact mood in individuals with rMDD, it does not seem to reliably lower mood in HCs [118]. Furthermore, although Roiser et al. [59] did observe elevated activity in the left habenula in rMDD patients, ATD did not significantly affect mood in their sample. Overall, in light of the current evidence, we cannot confidently assert that habenular hyperactivity exists in human depression. On the one hand, the study that was best designed found no evidence for habenular hyperactivity in depression [53]. On the other hand, three studies did point to habenular hyperactivity in depression [55, 57, 59]. However, because the relationship between ATD and depression is unclear, and because of the low resolution of ASL and PET images, results from the two ATD studies [55, 59], although coherent with habenular hyperactivity, cannot be regarded as a strong source of evidence.

Indirect data relevant to the matter of habenular hyperactivity in human depression have also been provided by studies employing intracerebral recording methods to measure LFPs from the habenula in patients undergoing DBS surgery. Intracerebral recordings offer a promising avenue to address whether the habenula is hyperactive in human depression. Because habenular intracerebral recordings have also been used in animal models, this method permits direct cross-species comparisons. This is critically important, as findings derived from invasive animal research may sometimes be difficult to relate to results from human non-invasive neuroimaging, thus impeding the translation of findings. Using the same tools across species has been proposed as a way to bridge the methodological gap between human and animal neuroscience in order to foster translation [119].

So far, four studies have used intracerebral recordings to study the habenula and its relationship with MDs in humans [60,61,62, 64]. While the results from one study could be coherent with the increased burst firing of the LHb described in rodent models [60], three studies reported results incoherent with animal findings and seemingly at odds with the theory of habenular hyperactivity in human depression [61, 62, 64]. Overall, no coherent picture emerges from these early studies using intracerebral recordings. Samples are too small to draw definitive conclusions, as each of the four studies included fewer than 10 participants. Moreover, the samples are heterogeneous, containing not only patients with MDD but also those with BD [60, 62] and schizophrenia [62]. Another thing to consider is that it is possible that LFPs recorded in the habenula also reflect activity from more distant sources [68, 69]. Indeed, volume conduction, which refers to the propagation of electrical potential to a location away from the source [120], may contaminate the signal [121].

Several activation studies compared the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) activity of the habenula between MDD patients and HCs while they completed a task in an MRI scanner [40, 53, 56, 58, 63]. Regrettably, because these studies measure the activity of the habenula during a task, they cannot directly answer the question of whether the baseline activity of the habenula is enhanced in human depression, as is the case in animal models. One finding, that of lower habenular activation in MDD when processing stimuli of negative motivational value, was reported in three different studies and hence merits further attention. So far, to our knowledge, animal studies have not investigated if there is a difference between depressed and non-depressed animals in LHb firing when encoding stimuli of negative motivational value. Therefore, the reviewed studies cannot be directly compared to the animal literature.

The habenula as a potential hub connecting the reward system to the DMN

Overall, results from connectivity studies were mostly unreplicated, conflicting, or could not be compared between studies because of methodological heterogeneity. Even the sole finding that was reported in at least three individual studies is not entirely convincing. Indeed, three studies reported higher RSFC between the left mPFC and the habenula in depression [35, 54, 87]. However, three similar studies did not report any significant difference in RSFC between the habenula and the mPFC [122,123,124]. Moreover, although the three studies [35, 54, 87] agree in suggesting higher RSFC between the habenula and the left mPFC in MDD, there is a caveat. Indeed, while one study observed this higher RSFC for the whole habenula [35], another detected it in the left habenula exclusively [87], and yet another observed it in the right habenula exclusively [54].

Variability between the studies may be a factor explaining some of the conflicting findings. For instance, the clinical populations within the samples examined were quite heterogeneous, which renders between-study comparisons difficult. Some samples included only a specific type of depressed patients (e.g., unmedicated MDD, TRD, subclinical depression (SD)). Other studies assigned patients to different groups based on specific characteristics (e.g., MDD with versus without suicidal ideation, psychiatric inpatients with versus without a history of past suicide attempts). Research questions also varied across studies (e.g., response to treatment, prediction of treatment response, comparing patients with MDs versus HCs) and the analyses performed were diverse (e.g., static functional connectivity, dynamic functional connectivity, effective connectivity, network analysis). Another source of variability is that some studies used seed-to-whole-brain analysis using the habenula as a seed, while other studies used seed-to-ROIs analysis. In addition, some studies used the whole habenula as a seed, while others separated the left and the right habenula.

Although connectivity results were challenging to interpret, a recurring pattern was the frequent report of DMN regions. Work on non-clinical populations has shown that the habenula is functionally connected to areas of the DMN such as the precuneus, PCC, mPFC, and PHG [35, 37, 38]. The DMN is thought to play a role in rumination [125, 126] and is one of the main networks disrupted in depression [127]. Importantly, a study in a rat model of depression has demonstrated a causal relationship between the LHb and the DMN [128]. Indeed, the study showed that inhibition of the LHb, which alleviates depressive symptoms in rodents [24], induces a decrease in DMN connectivity. This suggests that the habenula and the DMN may interact together in their involvement in depression. More specifically, there could be a relationship between habenular hyperactivity and the hyperconnectivity of the DMN observed in human depression [129, 130] (although hypoconnectivity has also been reported [131]).

In addition to the DMN, another core network involved in depression is the reward network [127], which encompasses the habenula [132]. Neuroscientific investigations about the DMN and the reward system have largely been pursued in isolation from each other [133]. Interestingly, efforts to integrate findings from these two fields have recently been undertaken. Indeed, it has been proposed that the DMN can be conceptualized as a reinforcement learning agent [133]. As such, the DMN’s role would be to optimize behavior, which involves the minimization of prediction errors to maximize reward over time. One possibility is that the habenula may act as hub linking the subcortical reward system with the cortical DMN. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), which is connected to the habenula and is part of the DMN, could act as the messenger allowing communication between the DMN and the habenula. According to Rolls [134], although the LHb’s activity correlates with RPEs, it is unlikely that the LHb is the structure computing these errors. Indeed, Rolls [134] proposes that the bulk of the computation is done by cortical areas, particularly the orbitofrontal cortex (encompassed in the vmPFC). The signal is then proposed to be sent to the LHb, which then relays it to structures such as the midbrain dopaminergic neurons [135]. Evidence from rodents suggests that the projection from the mPFC to the LHb [136] might be of critical importance to the etiology of depression. For instance, chemogenetic activation of this projection was shown to produce depressive-like symptoms in mice, whereas its inhibition has antidepressant effects [137]. In this review, we identified three studies reporting higher RSFC between the left mPFC and the habenula in depression [35, 54, 87]. This finding and results from preclinical studies suggest that the glutamatergic projection from mPFC neurons to the habenula may be hyperactive in depressed patients, thereby contributing to habenular hyperactivity (provided that habenular hyperactivity is indeed present in human depression, which, as stated above, has not been demonstrated yet).

Future research is needed to elucidate the connections between the reward system and the DMN as well as how this potentially relates to depression. Because of its extensive connections with the vmPFC, the habenula may be a key node allowing communication between these two networks and is thus a target for further investigations in the emergent research endeavor attempting to provide an integrative account of these two important brain networks.

Is the volume of the habenula altered in human depression?

Structural studies have mostly concentrated on habenular volume (14 studies). Five out of the seven studies that compared the volume of the habenula between depressed patients and HCs found no significant difference. One study observed a smaller volume of the right habenula in MDD patients (Cho, Park et al., [97]), while another found a larger bilateral habenular volume in MDD patients (Liu, Valton et al., [40]). Of the two studies examining differences in habenular volume between HCs and BD patients, neither found any significant group differences [92, 100].

Although habenular morphology has not been a great object of interest in animal models of depression, we know of two studies that addressed the subject. One study noted lower bilateral MHb volume in a mice model of MDs, but no difference for the LHb [138]. The other study observed lower volumes of both the bilateral MHb and LHb in rats exposed to chronic stress [139]. More research is needed to establish whether there exists a reduction in habenular volume in animal models of depression.

Overall, the reviewed data do not provide evidence for an alteration of habenular volume in MDs. An important consideration is that the methodological quality of the studies was quite varied. First, some studies [40, 53, 95] assessed habenular volume using Lawson’s method to identify the habenula [29], although this method was not designed for this purpose, as it relies on geometric delineation [140]. Moreover, the resolution of some of the studies was likely insufficient to clearly delineate the habenula. Indeed, Kim and colleagues [140] demonstrated that when high-resolution anatomical images from a 7 T scanner were down-sampled to 0.8 mm isotropic, subtle details aiding in habenular delineation were lost, though these details remained visible at 0.5 mm isotropic. Among volumetric studies, only four had a resolution of 0.7 mm or less in all planes [95,96,97,98], which one may argue is a bare minimum to be able to delineate the habenula with relatively good precision. Among these studies, three found no difference in habenular volume between MDD patients and HCs [95, 96, 98], while one study found that MDD patients had a significantly smaller right habenular volume than HCs [97]. Therefore, even among higher-quality studies, the evidence remains conflicting. Volumetric studies depend more heavily on precise delineation of habenular boundaries than functional studies, indicating that even the highest-quality research to date may lack the resolution and contrast needed to produce replicable results or detect subtle group differences. Although methods to improve volumetric study quality are available, researchers have yet to fully capitalize on recent advancements in imaging techniques for studying the habenula in MDs. Moving forward, volumetric studies specifically designed to assess habenular volume will be essential. Key improvements will include utilizing images with enhanced contrast over standard MPRAGE (e.g., MP2RAGE [141] or other myelin-sensitive imaging techniques), and leveraging UHF MRI to acquire higher-resolution images (e.g., 0.5 mm isotropic [140]).

As for DTI studies, they will also benefit from higher image resolution. For instance, using high resolution (i.e., 0.7 mm isotropic) DTI on a 7 T scanner, Strotman and colleagues were able to distinguish fiber from the LHb and MHb [142], which was not possible at lower resolutions [30].

Limitations and future directions

One noteworthy limitation of this review is that the protocol was not preregistered. Our review was also limited by the methodological shortcomings of individual studies. Despite methodological improvements over the last decades [30], precisely imaging the habenula remains a technical challenge. Some of the conflicting findings among reviewed studies may be explained by the small size of the habenula and its low contrast with neighboring structures, as this may have led to heterogeneity in the definition of the habenula. Variability in the methods used to segment the habenula may also have been at play. While most papers used a manual method or a semi-automated method involving manual steps (26 studies), other papers defined the habenula based on Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) coordinates thought to represent the location of the habenula (10 studies), which likely resulted in delineation inaccuracies, as the location of the habenula in normalized space varies between individuals [32]. Some papers also used brain atlases (3 studies) or fully automated segmentation methods (2 studies). Minor inaccuracies in defining the habenula might have led to signal corruption by adjacent structures or CSF. Another important shortcoming of many functional studies is the use of a lower image resolution (e.g., 3.5 mm isotropic), often explained by the use of a 3 Tesla MRI scanner. Given that the size of each habenula is 30 mm [3] at most [143], which corresponds to one 3 mm isotropic voxel, such a resolution may not be sufficient. This is why an increasing number of studies investigating the habenula have been using 7 Tesla MRI scanners [144]. Limited sample size in certain studies (e.g., there were 21 articles wherein at least one group had a sample size of 20 or less) also casts doubts on the reliability of some of the results. For instance, some inconsistencies in results might stem from underpowered studies unable to detect effects reported by others. Lastly, a limpid integration of the results is somewhat impeded by the diversity of the populations studied, which precluded a meta-analysis. Even within the depression continuum, there were significant differences between the samples regarding disease stage (e.g., first episode MDD, SD, rMDD).

As briefly noted in the introduction, research in healthy humans seems quite consistent with findings from animal studies, —with the caveat that we have not conducted a systematic review on this matter— indicating that the habenula is involved in coding negative RPEs [39,40,41,42,43] and is functionally connected to the VTA, MRN, DRN, and PAG [35,36,37,38]. These results indicate that neuroimaging measures of the habenula can be both robust and reliable in human studies. One potential reason for the discrepancy in the reliability of findings on the habenula in mood disorders (MDs) compared to healthy individuals may be that, due to the habenula’s low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), the statistical power of studies has been adequate to detect within-subject differences but not strong enough to identify between-subject differences. Another thing to consider is that resting-state studies in healthy humans have used on average longer resting-state sessions (5 min [37], 10 min [38], 60 min [35], and 60 min [36]), while out of the 26 resting-state samples reviewed here, only 7 samples had a scanning duration over 8 min, and only 3 samples over 9 min. Reliability of RSFC estimates could likely be enhanced in future studies by using longer resting-state sessions (i.e., at least 9 min [145]). Moreover, resting-state studies in healthy humans have used on average a much higher resolution (1.3 [38], 1.5 [37], and 2 [35, 36] mm isotropic).

To conduct better studies on the human habenula and enhance the replicability of findings, we offer various recommendations. First, when available, an MRI scanner with a higher field (e.g., 7 T rather than 3 T) should be used. UHF MRI will improve the resolution of both structural and functional MRI images, and enhance SNR [28]. Activity studies will also benefit, as task-related activation at 7 T is markedly enhanced, exhibiting higher percent signal changes [146, 147]. Additionally, resting-state studies will benefit, as at UHF, RSFC exhibits considerable improvements in test-retest reliability [148, 149]. Higher resolution also increases tissue contrast [28, 150], enabling better segmentation of structures with low contrast to neighboring structures, such as the habenula [142]. Optimizing anatomical image acquisition to accurately identify the habenula is paramount. Although the habenula has low anatomical contrast to the surrounding thalamus on MPRAGE images [30], new approaches have shown better contrast at 3 T (e.g., T1w over T2w, STAGE-enhanced T1W (T1WE) [30], or MP2RAGE [141] images). At higher resolution (e.g., 7 T scanner), MP2RAGE with 0.5 mm isotropic resolution has demonstrated clear habenula contrast [140].

Preprocessing should also be conducted with a tailored approach depending on the study’s purpose. For normalization, it is important to consider that the location of the habenula varies in spatially transformed images [32]. Accordingly, it has been suggested to omit spatial normalization and instead conduct functional analyses using a participant-specific habenula ROI [29]. For the same reason, atlas-based approaches, such as probability maps or using MNI coordinates, should be avoided for habenula identification [32]. A promising approach is to use automatic segmentation techniques to identify the habenula, which will save time and remove the subjectivity associated with manual delineation [30]. Similarly, it has been recommended that volumetric analyses be conducted in native space, as normalization may introduce errors in habenular volume measurements [32]. Special attention should also be given to physiological noise. Indeed, the habenula resides in close proximity to the third ventricule, and thus may be prone to physiological artifacts of cardiorespiratory origin (e.g., pulsations from blood flow and breathing). Thus, acquiring cardiac and respiratory data and correcting for physiological noise with tools such as the PhysIO Toolbox [151] may improve SNR.

Moving forward, transcending disciplinary boundaries between human and animal research will be essential to the translation of findings. Our results underscore how the current lack of permeability between these fields can hinder translation. For instance, very few studies included in this review directly tested the hypothesis of habenular hyperactivity (at rest) in human depression, although this is arguably the most important finding about the LHb derived from animal models of depression. Moreover, it is surprising that the volume of the habenula has been the subject of so much interest in humans, while this has not been of major interest in the animal literature. This may be due to an early report of reduced habenular volume in depressed patients [99].

In conclusion, our main findings can be summarized in three points. First, we found that the available evidence is not sufficient to either conclude the presence or the absence of habenular hyperactivity in human depression. In contrast, the finding of baseline habenular hyperactivity is widely replicated in animal models of depression (e.g., [16,17,18, 114]). Second, results from connectivity studies were mainly inconsistent across studies. However, one interesting observation is that regions of the DMN appeared to be overrepresented in the results. Findings from connectivity studies were difficult to compare to the animal literature, as fMRI has rarely been used in rodents to study the LHb in models of MDs, except for a handful of studies (e.g., [128, 152, 153]). Lastly, we found no evidence for habenular volumetric alterations in MDs. In rodents, two studies have investigated the matter. Both detected a decrease in MHb volume in depressed animals. One study found a decrease in LHb volume, while the other did not.

References

Herkenham M, Nauta WJ. Efferent connections of the habenular nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1979;187:19–47.

Viswanath H, Carter AQ, Baldwin PR, Molfese DL, Salas R. The medial habenula: still neglected. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;7:931.

Namboodiri VM, Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Stuber GD. The habenula. Curr Biol. 2016;26:R873–r877.

Chen S, Sun X, Zhang Y, Mu Y, Su D. Habenula bibliometrics: thematic development and research fronts of a resurgent field. Front Integr Neurosci. 2022;16:949162.

Hu H, Cui Y, Yang Y. Circuits and functions of the lateral habenula in health and in disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2020;21:277–95.

Ullsperger M, von Cramon DY. Error monitoring using external feedback: specific roles of the habenular complex, the reward system, and the cingulate motor area revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4308.

Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Lateral habenula as a source of negative reward signals in dopamine neurons. Nature. 2007;447:1111–5.

Matsumoto M, Hikosaka O. Two types of dopamine neuron distinctly convey positive and negative motivational signals. Nature. 2009;459:837–41.

Amo R, Fredes F, Kinoshita M, Aoki R, Aizawa H, Agetsuma M, et al. The habenulo-raphe serotonergic circuit encodes an aversive expectation value essential for adaptive active avoidance of danger. Neuron. 2014;84:1034–48.

Nuno-Perez A, Trusel M, Lalive AL, Congiu M, Gastaldo D, Tchenio A, et al. Stress undermines reward-guided cognitive performance through synaptic depression in the lateral habenula. Neuron. 2021;109:947–56.e945.

Halahakoon DC, Kieslich K, O’Driscoll C, Nair A, Lewis G, Roiser JP. Reward-processing behavior in depressed participants relative to healthy volunteers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:1286–95.

Chen C, Takahashi T, Nakagawa S, Inoue T, Kusumi I. Reinforcement learning in depression: a review of computational research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:247–67.

Eshel N, Roiser JP. Reward and punishment processing in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:118–24.

Batalla A, Homberg JR, Lipina TV, Sescousse G, Luijten M, Ivanova SA, et al. The role of the habenula in the transition from reward to misery in substance use and mood disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:276–85.

Gold PW, Kadriu B. A major role for the lateral habenula in depressive illness: physiologic and molecular mechanisms. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:320.

Caldecott-Hazard S, Mazziotta J, Phelps M. Cerebral correlates of depressed behavior in rats, visualized using 14C- 2-deoxyglucose autoradiography. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1951–61.

Cerniauskas I, Winterer J, de Jong JW, Lukacsovich D, Yang H, Khan F, et al. Chronic stress induces activity, synaptic, and transcriptional remodeling of the lateral habenula associated with deficits in motivated behaviors. Neuron. 2019;104:899–915.e898.

Tchenio A, Lecca S, Valentinova K, Mameli M. Limiting habenular hyperactivity ameliorates maternal separation-driven depressive-like symptoms. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1135.

Cui Y, Hu S, Hu H. Lateral habenular burst firing as a target of the rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine. Trends Neurosci. 2019;42:179–91.

Yang Y, Wang H, Hu J, Hu H. Lateral habenula in the pathophysiology of depression. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2018;48:90–96.

Stern WC, Johnson A, Bronzino JD, Morgane PJ. Effects of electrical stimulation of the lateral habenula on single-unit activity of raphe neurons. Exp Neurol. 1979;65:326–42.

Christoph GR, Leonzio RJ, Wilcox KS. Stimulation of the lateral habenula inhibits dopamine-containing neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of the rat. J Neurosci. 1986;6:613–9.

Proulx CD, Aronson S, Milivojevic D, Molina C, Loi A, Monk B, et al. A neural pathway controlling motivation to exert effort. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:5792–7.

Winter C, Vollmayr B, Djodari-Irani A, Klein J, Sartorius A. Pharmacological inhibition of the lateral habenula improves depressive-like behavior in an animal model of treatment resistant depression. Behav Brain Res. 2011;216:463–5.

Yang LM, Hu B, Xia YH, Zhang BL, Zhao H. Lateral habenula lesions improve the behavioral response in depressed rats via increasing the serotonin level in dorsal raphe nucleus. Behav Brain Res. 2008;188:84–90.

Amat J, Sparks PD, Matus-Amat P, Griggs J, Watkins LR, Maier SF. The role of the habenular complex in the elevation of dorsal raphe nucleus serotonin and the changes in the behavioral responses produced by uncontrollable stress. Brain Res. 2001;917:118–26.

Yang Y, Cui Y, Sang K, Dong Y, Ni Z, Ma S, et al. Ketamine blocks bursting in the lateral habenula to rapidly relieve depression. Nature. 2018;554:317–22.

Sclocco R, Beissner F, Bianciardi M, Polimeni JR, Napadow V. Challenges and opportunities for brainstem neuroimaging with ultrahigh field MRI. Neuroimage. 2018;168:412–26.

Lawson RP, Drevets WC, Roiser JP. Defining the habenula in human neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage. 2013;64:722–7.

Bian B, Zhang B, Wong C, Dou L, Pan X, Wang H, et al. Recent advances in habenula imaging technology: a comprehensive review. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2024;59:737–46.

Kim J-W, Xu J Automated human habenula segmentation from T1-weighted magnetic resonance images using V-Net. bioRxiv: 2022.2001.2025.477768 [Preprint]. 2022. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.25.477768v1.

Milotta G, Green I, Roiser JP, Callaghan MF. In vivo multi-parameter mapping of the habenula using MRI. Sci Rep. 2023;13:3754.

Epstein EL, Hurley RA, Taber KH. The habenula’s role in adaptive behaviors: contributions from neuroimaging. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;30:A4–4.

Quina LA, Tempest L, Ng L, Harris JA, Ferguson S, Jhou TC, et al. Efferent pathways of the mouse lateral habenula. J Comp Neurol. 2015;523:32–60.

Ely BA, Xu J, Goodman WK, Lapidus KA, Gabbay V, Stern ER. Resting-state functional connectivity of the human habenula in healthy individuals: associations with subclinical depression. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37:2369–84.

Ely BA, Stern ER, Kim JW, Gabbay V, Xu J. Detailed mapping of human habenula resting-state functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2019;200:621–34.

Hétu S, Luo Y, Saez I, D’Ardenne K, Lohrenz T, Montague PR. Asymmetry in functional connectivity of the human habenula revealed by high-resolution cardiac-gated resting state imaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37:2602–15.

Torrisi S, Nord CL, Balderston NL, Roiser JP, Grillon C, Ernst M. Resting state connectivity of the human habenula at ultra-high field. Neuroimage. 2017;147:872–9.

Shepard PD, Holcomb HH, Gold JM. Schizophrenia in translation: the presence of absence: habenular regulation of dopamine neurons and the encoding of negative outcomes. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:417–21.

Liu WH, Valton V, Wang LZ, Zhu YH, Roiser JP. Association between habenula dysfunction and motivational symptoms in unmedicated major depressive disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2017;12:1520–33.

Yoshino A, Okamoto Y, Sumiya Y, Okada G, Takamura M, Ichikawa N, et al. Importance of the habenula for avoidance learning including contextual cues in the human brain: a preliminary fMRI study. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:165.

Hennigan K, D’Ardenne K, McClure SM. Distinct midbrain and habenula pathways are involved in processing aversive events in humans. J Neurosci. 2015;35:198–208.

Salas R, Baldwin P, de Biasi M, Montague PR. BOLD responses to negative reward prediction errors in human habenula. Front Hum Neurosci. 2010;4:36.

Aizawa H, Zhu M. Toward an understanding of the habenula’s various roles in human depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;73:607–12.

Browne CA, Hammack R, Lucki I. Dysregulation of the lateral habenula in major depressive disorder. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2018;10:46.

Zhang GM, Wu HY, Cui WQ, Peng W. Multi-level variations of lateral habenula in depression: a comprehensive review of current evidence. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1043846.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Study Quality Assessment Tools. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health‐topics/study‐quality‐assessment‐tools., 2021, Accessed 2021.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders(5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Haddaway NR, Page MJ, Pritchard CC, McGuinness LA. PRISMA2020: an R package and shiny app for producing PRISMA 2020-compliant flow diagrams, with interactivity for optimised digital transparency and open synthesis. Campbell Syst Rev. 2022;18:e1230.

Elias GJB, Germann J, Loh A, Boutet A, Pancholi A, Beyn ME, et al. Habenular involvement in response to subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for depression. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:810777.

Gosnell SN, Curtis KN, Velasquez K, Fowler JC, Madan A, Goodman W, et al. Habenular connectivity may predict treatment response in depressed psychiatric inpatients. J Affect Disord. 2019;242:211–9.

Lawson RP, Nord CL, Seymour B, Thomas DL, Dayan P, Pilling S, et al. Disrupted habenula function in major depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:202–8.

Luan SX, Zhang L, Wang R, Zhao H, Liu C. A resting-state study of volumetric and functional connectivity of the habenular nucleus in treatment-resistant depression patients. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01229.

Morris JS, Smith KA, Cowen PJ, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ. Covariation of activity in habenula and dorsal raphé nuclei following tryptophan depletion. Neuroimage. 1999;10:163–72.

Willinger D, Karipidis II, Neuer S, Emery S, Rauch C, Häberling I, et al. Maladaptive avoidance learning in the orbitofrontal cortex in adolescents with major depression. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2022;7:293–301.

Carlson PJ, Diazgranados N, Nugent AC, Ibrahim L, Luckenbaugh DA, Brutsche N, et al. Neural correlates of rapid antidepressant response to ketamine in treatment-resistant unipolar depression: a preliminary positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:1213–21.

Furman DJ, Gotlib IH. Habenula responses to potential and actual loss in major depression: preliminary evidence for lateralized dysfunction. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2016;11:843–51.

Roiser JP, Levy J, Fromm SJ, Nugent AC, Talagala SL, Hasler G, et al. The effects of tryptophan depletion on neural responses to emotional words in remitted depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:441–50.

Sonkusare S, Ding Q, Zhang Y, Wang L, Gong H, Mandali A, et al. Power signatures of habenular neuronal signals in patients with bipolar or unipolar depressive disorders correlate with their disease severity. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:72.

Zhang C, Zhang Y, Luo H, Xu X, Yuan TF, Li D, et al. Bilateral habenula deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: clinical findings and electrophysiological features. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:52.

Huang Y, Sun B, Debarros J, Zhang C, Zhan S, Li D, et al. Increased theta/alpha synchrony in the habenula-prefrontal network with negative emotional stimuli in human patients. Elife. 2021;10:e65444.

Kumar P, Goer F, Murray L, Dillon DG, Beltzer ML, Cohen AL, et al. Impaired reward prediction error encoding and striatal-midbrain connectivity in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:1581–8.

Wang Z, Cai X, Qiu R, Yao C, Tian Y, Gong C, et al. Case report: lateral habenula deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Front Psychiatry. 2021;11:616501.

Feng CM, Narayana S, Lancaster JL, Jerabek PA, Arnow TL, Zhu F, et al. CBF changes during brain activation: fMRI vs. PET. Neuroimage. 2004;22:443–6.

Young SN. The effect of raising and lowering tryptophan levels on human mood and social behaviour. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20110375.

Destexhe A, Bédard C Local field potentials: LFP. In: Jaeger D, Jung R (eds). Encyclopedia of Computational Neuroscience. Springer New York: New York, NY, 2020, pp 1-12.

Herreras O. Local field potentials: myths and misunderstandings. Front Neural Circuits. 2016;10:101.

Kajikawa Y, Schroeder CE. How local is the local field potential? Neuron. 2011;72:847–58.

Gao R, Peterson EJ, Voytek B. Inferring synaptic excitation/inhibition balance from field potentials. Neuroimage. 2017;158:70–78.

McCormick DA, Bal T. Sleep and arousal: thalamocortical mechanisms. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:185–215.

Zeldenrust F, Wadman WJ, Englitz B. Neural coding with bursts-current state and future perspectives. Front Comput Neurosci. 2018;12:48.

Zhang Y, Ma L, Zhang X, Yue L, Wang J, Zheng J, et al. Deep brain stimulation in the lateral habenula reverses local neuronal hyperactivity and ameliorates depression-like behaviors in rats. Neurobiol Dis. 2023;180:106069.

Mao CP, Wu Y, Yang HJ, Qin J, Song QC, Zhang B, et al. Altered habenular connectivity in chronic low back pain: An fMRI and machine learning study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2023;44:4407–21.

Wills KE, Gosnell SN, Curtis KN, Velasquez K, Fowler JC, Salas R. Altered habenula to locus coeruleus functional connectivity in past anorexia nervosa suggests correlation with suicidality: a pilot study. Eat Weight Disord. 2020;25:1475–80.

Chen C, Wang M, Yu T, Feng W, Xu Y, Ning Y, et al. Habenular functional connections are associated with depression state and modulated by ketamine. J Affect Disord. 2024;345:177–85.

Rivas-Grajales AM, Salas R, Robinson ME, Qi K, Murrough JW, Mathew SJ. Habenula connectivity and intravenous ketamine in treatment-resistant depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;24:383–91.

Wang M, Chen X, Hu Y, Zhou Y, Wang C, Zheng W, et al. Functional connectivity between the habenula and default mode network and its association with the antidepressant effect of ketamine. Depress Anxiety. 2022;39:352–62.

Chen G, Chen P, Yang Z, Ma W, Yan H, Su T, et al. Increased functional connectivity between the midbrain and frontal cortex following bright light therapy in subthreshold depression: a randomized clinical trial. Am Psychol. 2023;79:437–50.

Gao J, Li Y, Wei Q, Li X, Wang K, Tian Y, et al. Habenula and left angular gyrus circuit contributes to response of electroconvulsive therapy in major depressive disorder. Brain Imaging Behav. 2021;15:2246–53.

Jung JY, Cho SE, Kim N, Kang CK, Kang SG. Decreased resting-state functional connectivity of the habenula-cerebellar in a major depressive disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:925823.

Amiri S, Arbabi M, Rahimi M, Parvaresh-Rizi M, Mirbagheri MM. Effective connectivity between deep brain stimulation targets in individuals with treatment-resistant depression. Brain Commun. 2023;5:fcad256.

Poblete G, Nguyen T, Gosnell S, Sofela O, Patriquin M, Mathew SJ, et al. A novel approach to link genetics and human MRI identifies AKAP7-dependent subicular/prefrontal functional connectivity as altered in suicidality. Chronic Stress. 2022;6:24705470221083700.

Amiri S, Arbabi M, Kazemi K, Parvaresh-Rizi M, Mirbagheri MM. Characterization of brain functional connectivity in treatment-resistant depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;111:110346.

Zhu Y, Qi S, Zhang B, He D, Teng Y, Hu J, et al. Connectome-based biomarkers predict subclinical depression and identify abnormal brain connections with the lateral habenula and thalamus. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:371.

Wang J, Zuo X, He Y. Graph-based network analysis of resting-state functional MRI. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010;4:16.

Zhu Z, Wang S, Lee TMC, Zhang R. Habenula functional connectivity variability increases with disease severity in individuals with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2023;333:216–24.

Johnston BA, Steele JD, Tolomeo S, Christmas D, Matthews K. Structural MRI-based predictions in patients with Treatment-Refractory Depression (TRD). PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132958.

Lanzenberger R, Kranz GS, Haeusler D, Akimova E, Savli M, Hahn A, et al. Prediction of SSRI treatment response in major depression based on serotonin transporter interplay between median raphe nucleus and projection areas. Neuroimage. 2012;63:874–81.

Wang F, Zhang M, Li Y, Li Y, Gong H, Li J, et al. Alterations in brain iron deposition with progression of late-life depression measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based quantitative susceptibility mapping. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022;12:3873–88.

Carceller-Sindreu M, de Diego-Adeliño J, Serra-Blasco M, Vives-Gilabert Y, Martín-Blanco A, Puigdemont D, et al. Volumetric MRI study of the habenula in first episode, recurrent and chronic major depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:2015–21.

Germann J, Gouveia FV, Martinez RCR, Zanetti MV, de Souza Duran FL, Chaim-Avancini TM, et al. Fully automated habenula segmentation provides robust and reliable volume estimation across large magnetic resonance imaging datasets, suggesting intriguing developmental trajectories in psychiatric disease. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2020;5:923–9.

Wang J, Ji G, Li G, Hu Y, Zhang W, Ji W, et al. Habenular connectivity predict weight loss and negative emotional-related eating behavior after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Cereb Cortex. 2023;33:2037–47.

Cho SE, Kim N, Na KS, Kang CK, Kang SG. Thalamo-habenular connection differences between patients with major depressive disorder and normal controls. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:699416.

Aftanas LI, Filimonova EA, Anisimenko MS, Berdyugina DA, Rezakova MV, Simutkin GG, et al. The habenular volume and PDE7A allelic polymorphism in major depressive disorder: preliminary findings. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2023;24:223–32.

Schmidt FM, Schindler S, Adamidis M, Strauß M, Tränkner A, Trampel R, et al. Habenula volume increases with disease severity in unmedicated major depressive disorder as revealed by 7T MRI. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;267:107–15.

Cho SE, Park CA, Na KS, Chung C, Ma HJ, Kang CK, et al. Left-right asymmetric and smaller right habenula volume in major depressive disorder on high-resolution 7-T magnetic resonance imaging. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0255459.

Savitz JB, Nugent AC, Bogers W, Roiser JP, Bain EE, Neumeister A, et al. Habenula volume in bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:336–43.

Ranft K, Dobrowolny H, Krell D, Bielau H, Bogerts B, Bernstein HG. Evidence for structural abnormalities of the human habenular complex in affective disorders but not in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2010;40:557–67.

Schafer M, Kim JW, Joseph J, Xu J, Frangou S, Doucet GE. Imaging habenula volume in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:456.

Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Field AS. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:316–29.

Nakajo H, Tsuboi T, Okamoto H. The behavioral paradigm to induce repeated social defeats in zebrafish. Neurosci Res. 2020;161:24–32.

Shumake J, Edwards E, Gonzalez-Lima F. Opposite metabolic changes in the habenula and ventral tegmental area of a genetic model of helpless behavior. Brain Res. 2003;963:274–81.

Petcharunpaisan S, Ramalho J, Castillo M. Arterial spin labeling in neuroimaging. World J Radiol. 2010;2:384–98.

Alsaedi A, Thomas D, Bisdas S, Golay X. Overview and critical appraisal of arterial spin labelling technique in brain perfusion imaging. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2018;2018:5360375.

Gauthier CJ, Fan AP. BOLD signal physiology: models and applications. Neuroimage. 2019;187:116–27.

Wager TD, Lindquist MA. Principles of fMRI. NY: Leanpub. 2015;4:115.

Rodgers ZB, Detre JA, Wehrli FW. MRI-based methods for quantification of the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:1165–85.

Liu TT. Noise contributions to the fMRI signal: An overview. Neuroimage. 2016;143:141–51.

Wang J, Aguirre GK, Kimberg DY, Roc AC, Li L, Detre JA. Arterial spin labeling perfusion fMRI with very low task frequency. Magnetic Reson Med. 2003;49:796–802.

Jahng G-H, Song E, Zhu X-P, Matson GB, Weiner MW, Schuff N. Human brain: reliability and reproducibility of pulsed arterial spin-labeling perfusion MR imaging. Radiology. 2005;234:909–16.

Hermes M, Hagemann D, Britz P, Lieser S, Rock J, Naumann E, et al. Reproducibility of continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI after 7 weeks. Magma. 2007;20:103–15.

Floyd TF, Maldjian J, Gonzales-Atavales J, Alsop D, Detre JA Test-retest stability with continuous arterial spin labeled (CASL) perfusion MRI in regional measurement of cerebral blood flow. Proc Int Soc Magn Reson Med. 2001:1569.

Li B, Piriz J, Mirrione M, Chung C, Proulx CD, Schulz D, et al. Synaptic potentiation onto habenula neurons in the learned helplessness model of depression. Nature. 2011;470:535–9.

Hernandez-Garcia L, Lahiri A, Schollenberger J. Recent progress in ASL. Neuroimage. 2019;187:3–16.

Yu F, Wu C, Yin Y, Wei X, Yang X, Lui S, et al. Research applications of cerebral perfusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in neuroscience. In: PET/MR: Functional and molecular imaging of neurological diseases and neurosciences. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2023. pp. 79–92.

Lindner T, Bolar DS, Achten E, Barkhof F, Bastos-Leite AJ, Detre JA, et al. Current state and guidance on arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI in clinical neuroimaging. Magn Reson Med. 2023;89:2024–47.

Ruhé HG, Mason NS, Schene AH. Mood is indirectly related to serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine levels in humans: a meta-analysis of monoamine depletion studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:331–59.

Barron HC, Mars RB, Dupret D, Lerch JP, Sampaio-Baptista C. Cross-species neuroscience: closing the explanatory gap. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2021;376:20190633.

Lagerlund TD, Rubin DI, Daube JR 929Volume conduction. In: Rubin DI, Daube JR (eds). Clinical Neurophysiology. Oxford University Press 2016, p 0.

Bertone-Cueto NI, Makarova J, Mosqueira A, García-Violini D, Sánchez-Peña R, Herreras O, et al. Volume-conducted origin of the field potential at the lateral habenula. Front Syst Neurosci. 2019;13:78.

Su T, Chen B, Yang M, Wang Q, Zhou H, Zhang M, et al. Disrupted functional connectivity of the habenula links psychomotor retardation and deficit of verbal fluency and working memory in late‐life depression. CNS Neurosci Therapeutics. 2023;30:e14490.

Wu Z, Wang C, Ma Z, Pang M, Wu Y, Zhang N, et al. Abnormal functional connectivity of habenula in untreated patients with first-episode major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2020;285:112837.

Yang L, Jin C, Qi S, Teng Y, Li C, Yao Y, et al. Alterations of functional connectivity of the lateral habenula in subclinical depression and major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:588.

Chen X, Chen NX, Shen YQ, Li HX, Li L, Lu B, et al. The subsystem mechanism of default mode network underlying rumination: a reproducible neuroimaging study. Neuroimage. 2020;221:117185.

Zhou HX, Chen X, Shen YQ, Li L, Chen NX, Zhu ZC, et al. Rumination and the default mode network: meta-analysis of brain imaging studies and implications for depression. Neuroimage. 2020;206:116287.

Li BJ, Friston K, Mody M, Wang HN, Lu HB, Hu DW. A brain network model for depression: from symptom understanding to disease intervention. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:1004–19.

Clemm von Hohenberg C, Weber-Fahr W, Lebhardt P, Ravi N, Braun U, Gass N, et al. Lateral habenula perturbation reduces default-mode network connectivity in a rat model of depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:68.

Kaiser RH, Andrews-Hanna JR, Wager TD, Pizzagalli DA. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:603–11.

Liang S, Deng W, Li X, Greenshaw AJ, Wang Q, Li M, et al. Biotypes of major depressive disorder: neuroimaging evidence from resting-state default mode network patterns. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;28:102514.

Yan CG, Chen X, Li L, Castellanos FX, Bai TJ, Bo QJ, et al. Reduced default mode network functional connectivity in patients with recurrent major depressive disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:9078–83.

Proulx CD, Hikosaka O, Malinow R. Reward processing by the lateral habenula in normal and depressive behaviors. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1146–52.

Dohmatob E, Dumas G, Bzdok D. Dark control: the default mode network as a reinforcement learning agent. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41:3318–41.

Rolls ET. The roles of the orbitofrontal cortex via the habenula in non-reward and depression, and in the responses of serotonin and dopamine neurons. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;75:331–4.

Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:503–13.