Abstract

Increases in impulsivity and negative affect (e.g., neuroticism) are common during adolescence and are both associated with risk for alcohol-use initiation and other risk behaviors. Whole-brain functional connectivity approaches—when coupled with appropriate cross-validation—enable identification of complex neural networks subserving individual differences in dimensional traits (hereafter referred to as ‘neural signatures’). Here, we analyzed functional connectivity data acquired at age 19 from individuals enrolled in a multisite European study of adolescent development (N ~ 1100) using connectome-based predictive modeling. Network anatomies of these dimensional phenotypes were compared with one another and with a previously identified alcohol-use risk network to identify shared and unique neural mechanisms. Models accurately predicted both impulsivity and neuroticism (r’s ~ 0.17-0.19, p’s < 0.05), and successfully generalized to an external sample. The impulsivity network was predominantly characterized by motor/sensory-related connections. By contrast, the neural signature of neuroticism was relatively more distributed across multiple canonical networks, including motor/sensory, default mode, subcortical, frontoparietal and cerebellar networks. Very few connections were common to both impulsivity and neuroticism networks. Moreover, while ~10-20% of the connections from each trait overlapped with the alcohol-use risk network, these connections were distinct between the two traits. This study for the first time identifies functional connectivity signatures of two common risk factors for alcohol-use in youth—impulsivity and neuroticism. Consistent with current equifinality-based conceptions of development, few connections predicted both impulsivity and neuroticism, indicating that the neural signatures of these two traits are relatively distinct despite both being implicated in alcohol-use risk and a wide array of behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Impulsivity (i.e., the tendency to act without foresight [1]) and neuroticism (i.e., the tendency to experience negative affect [2]) are two broad cognitive traits that are known to be risk factors for a wide range of psychopathologies, including substance and alcohol use disorders (SUD/AUD) and mood and anxiety disorders. Though a large body of research has investigated the neural correlates of impulsivity and neuroticism, most of this work focused on investigating either structural anatomical features and/or localized, functional activation-based properties of a constrained set of brain regions [1, 3, 4]. Thus, relatively little is known about brain-wide functional connectivity patterns subserving individual differences in impulsivity and neuroticism, especially during adolescence when many psychiatric disorders begin to emerge [5]. In addition, little is known about the neural mechanisms through which impulsivity and neuroticism manifest as risk factors for psychopathology. For example, it is unclear whether the neural substrates of impulsivity and neuroticism overlap with one another nor whether they overlap with those implicated in common adolescent risk behaviors, such as experimentation with alcohol and other substances. Here, we investigate these questions using the prototypical risk behavior of adolescent alcohol use.

Alcohol is the most commonly used substance in youth—with approximately 33% of high school students reporting past month alcohol-use—and alcohol misuse is a leading cause of disability and mortality in youth [6,7,8,9]. A large body of literature has demonstrated that impulsivity and neuroticism are particularly onerous risk factors for alcohol misuse [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Impulsivity measures broadly are positively associated with various measures of alcohol consumption and problematic alcohol use behaviors in youth [10, 11], and tend to be associated with social and/or enhancement drinking motives [12, 18], especially among college students involved in social environments with high drinking norms [18]. On the other hand, neuroticism/negative emotionality is found to be heightened among a subset of youth who are more likely to engage in solitary drinking, and drinking with the motive to cope with negative emotions (e.g., distress, hopelessness, loneliness) [12, 18, 20, 21]. While negative affect and drinking-to-cope motives are less commonly observed among adolescent drinkers (relative to drinking to enhance social experience/ positive emotions) in general, a substantial body of evidence demonstrates their importance in predicting problematic alcohol use [22,23,24,25]. Moreover, research using latent growth models also suggests that changes in problematic alcohol behaviors are associated with changes in both neuroticism and impulsivity during emerging adulthood [14], further highlighting the longitudinal relevance of both traits in alcohol misuse across development and into adulthood.

A large body of research has investigated the neural correlates of impulsivity and neuroticism. Collectively, this work suggests that impulsivity is mediated by sensory-motor and cortico-limbic systems involved in regulatory (e.g., ventral and medial PFC), reward (e.g., ventral striatum, midbrain) and valence (e.g., anterior cingulate, amygdala) processes, and that neuroticism is associated with emotion regulatory regions including the amygdala, insula, superior and middle temporal gyrus, striatum, hippocampus, and supramarginal gyrus [3, 4, 26,27,28,29]. However, as most of this work focused on investigating either structural anatomical features and/or localized, functional activation-based properties of a constrained set of brain regions associated with each trait [1, 3, 4], relatively little is known about brain-wide functional connectivity patterns encoding individual differences in impulsivity and neuroticism, particularly during adolescence when many psychiatric disorders begin to manifest [5]. Thus, while some research indicates that etiological contributions of impulsivity and neuroticism to alcohol-use risk in youth may be dissociable at the behavioral level [12, 15], it remains unknown whether and how impulsivity and neuroticism might independently contribute to alcohol misuse on a neurobiological level.

The present study builds on our recent work in which we used a whole-brain machine learning approach to identify an ‘alcohol-use risk’ network in a large cohort of adolescents [30]. This alcohol-use risk network not only predicted current alcohol use (as quantified by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; AUDIT) at age 19, but also predicted future alcohol use using brain data from 5 years prior, and was further replicated in an external sample. Here, we adopt a similar approach, connectome-based predictive modeling (CPM)—a data-driven, machine learning approach—to identify and compare functional connectivity signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism in the same cohort of youth (N ~ 1100). By identifying functional connectivity signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism—and assessing how they might overlap with alcohol-use risk on a neurobiological level—we aim to enhance mechanistic understanding of how different risk factors might jointly (or independently) contribute to alcohol misuse in youth.

In light of recent findings that a given neurobiological correlate may manifest as distinct behaviors in males and females [31], we further explore potential sex differences in the functional connectivity signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism. Based on classic models focusing on inhibitory ‘top-down’ and subcortical ‘bottom-up’ developmental networks [32, 33], and more recent evidence that somato-motor dysconnectivity is implicated in impulsivity- and neuroticism-related psychiatric disorders [34] (e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorders), we anticipated that the neural signatures of both impulsivity and neuroticism would involve frontoparietal, subcortical and motor/sensory networks. Furthermore, we also anticipated that the neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism would involve dissociable connections, and each would overlap (at least partially) with the previously identified ‘alcohol-use risk’ network. Finally, we tested the external validity of our findings in an independent external sample of youth from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development℠ Study (ABCD Study®).

Methods and materials

Overview

Data for the primary analysis were collected as part of the IMAGEN study, a longitudinal, multi-site investigation of adolescent neurodevelopment in Europe comprising data from ~2000 individuals [35] including neuroimaging data acquired at age 19. Participants in this cohort are primarily White European and approximately 50% female (see Supplemental Information). The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline, and was approved by the institutional ethics committee of King’s College London (PNM/10/11-126), University of Nottingham (D/11/2007), Trinity College Dublin (SPREC092007-01), Technische Universitat Dresden (EK 235092007), Commissariat a l’Energie Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives, INSERM (2007-A00778-45), University Medical Center at the University of Hamburg (M-191/07) and in Germany at medical ethics committee of the University of Heidelberg (2007-024N-MA) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was provided by a parent or guardian, and verbal assent was provided by the participating adolescent. See Fig. 1 for a schematic overview of data analysis steps, and Supplemental Information for details of the power analysis conducted for determining sample size.

With the fMRI data (while performing the SST task) collected at age 19 in the IMAGEN study, we parcellated the brain using the 268-node Shen atlas and computed Pearson’s correlation for all pairwise combinations of the mean time course of the nodes to estimate brain-wide functional connectivity. We then used the functional connectivity data to run ten-fold, cross-validated CPM analyses to identify neural networks that predict impulsivity and neuroticism measures and obtain brain-behavior association models. We externally validated the CPM models using data from the ABCD study. We conducted three main analyses: 1) anatomical summarization of the neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism based on their overlap with canonical neural networks, 2) comparison of impulsivity and neuroticism signatures to identify their unique vs. shared anatomical features, and 3) comparison of the impulsivity and neuroticism signatures with a recently identified neural network implicated in alcohol-use risk.

Measures of impulsivity, neuroticism, and alcohol use

Impulsivity was assessed using the impulsivity measure in the Substance Use Risk Profile Scale [36] (mean: 2.20, standard deviation: 0.43), and neuroticism was assessed using the neuroticism measure in the NEO Five-Factor Inventory [37] (NEO-FFI; mean: 1.74, standard deviation: 0.69). Alcohol-use risk was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test [38, 39] (mean: 5.62, standard deviation: 4.43), as in our prior work [30]. See the Supplemental Information for a detailed description of the measures.

Inhibitory control task and pre-processing

Since the alcohol-use risk network was identified using connectivity data acquired during the stop signal task (SST) [30], we here also analyzed neuroimaging data acquired during the SST. The SST task is a widely used inhibitory control task. During each trial in the SST task, participants were presented with a “Go” stimulus, which was either a left or right arrow, and asked to indicate the direction of the arrow via a button press. In 20% of trials, the ‘Go’ stimuli were followed by a ‘Stop’ signal, signaling the participants to refrain from their button press response. The task lasted for a total of 11 min and data were acquired using repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) = 2200/30 ms. Details of neuroimaging acquisition are provided in the Supplemental Information.

Neuroimaging data (N = 1407, details in SI) were pre-processed using a well-validated pipeline, as in previous studies [30, 40]. Specifically, we first use Statistical Parametric Mapping software package SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London) for slice-timing correction, motion correction, non-linear warping of time series data onto MNI space using a custom EPI template, and Gaussian-smoothing at 5 mm-full width half maximum. Next, we utilized the BioImage Suite to perform additional preprocessing steps, including regression of 24 motion parameters and mean time courses in white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and grey matter; high-pass filtering to correct linear, quadratic, and cubic drift; and low-pass filtering.

After preprocessing, we constructed whole-brain functional connectivity matrices using BioImage Suite, following previously described methods [41,42,43]. Consistent with prior work, connectivity matrices were generated using the entirety of the timecourse with no modeling of task events [30, 44,45,46]. Specifically, individual participant whole-brain data were parcellated using the Shen 268-node brain atlas, which includes the cortex, subcortex, and cerebellum [47]. We then calculated the mean time course of voxels within each node, computed Pearson’s correlations for all possible pairwise combinations of the 268 nodes to estimate region-by-region functional connectivity, and transformed the Pearson’s r values to z values using Fisher’s z-transformation to create individual participant 268 × 268 connectivity matrices.

Having generated the functional connectivity matrices, we then performed quality control steps to exclude matrices based on the following criteria previously described [30]: mean framewise displacement > 0.2 mm; missing edges or failed symmetry checks; summed connectivity values and the standard deviation for the whole brain that met outlier criteria (any data points outside the range between 25th percentile − 1.5*interquartile range and 75th percentile + 1.5*interquartile range); missing complete behavioral measures. Completion of these quality control steps resulted in final sample sizes of N = 1138 for inclusion in the CPM of impulsivity and of N = 1153 in the CPM of neuroticism (see details in the Supplemental Information).

Connectome-based predictive modeling (CPM)

CPM is a data-driven method, incorporating stringent cross-validation, for identifying neural networks associated with a given behavior or phenotype. During training, CPM takes connectivity matrices and behavioral data (i.e., measures of impulsivity and neuroticism) as input to identify connections (hereafter referred to as ‘edges’) correlated with the behavioral variable of interest (p < 0.05), sums the combined strength of the identified edges, and constructs a predictive model that assumes linear relationships between the summed strength of the significant edges and the behavioral data. The resultant model is then applied to the held-out testing data set to generate predictions (e.g., of impulsivity or neuroticism) from functional connectivity, and model performance (i.e., correspondence between predicted and actual values) is assessed using Pearson’s correlations.

Here, we adopted CPM with ten-fold cross-validation, such that data were randomly split into ten folds, nine folds of which were used for training and the tenth fold (the ‘left-out’ fold) was used for model testing in an iterative manner (see Fig. 1). Statistical significance was determined via permutation testing in which a null distribution was generated over 1000 permutations and p was determined as:

Finally, to prevent overfitting to a given random 10-fold split, CPMs with 10-fold CV were repeated 100 times and ractual was defined as the mean across these 100 iterations, consistent with current recommendations [48]. Edges consistently identified as significant predictors across the 100 repeats (defined as either consistent across 75% or across 100% of iterations) were retained and mapped back to underlying brain anatomy.

To test for potential sex differences, exploratory sex-specific CPMs were run using the methods described above. Identified neural signatures were then used to cross-predict the behavioral measures of the other sex. In addition to ten-fold cross-validated CPM, we also conducted a separate leave-one-site-out cross-validated CPM for impulsivity and neuroticism, separately, to ensure any resulting patterns observed are not driven by site differences. Finally, in light of previous research on the association between in-scanner motion and trait impulsivity [49], we also ran separate CPMs controlling for mean framewise displacement for impulsivity and neuroticism via partial correlation analysis during the CPM feature-selection phase, as in prior work [40].

Network anatomy, virtual lesioning and identification of shared edges

Per recommendations for CPM best practices [40, 48], we characterized the anatomy of the neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism based on their overlap with ten well-established large-scale canonical neural networks (e.g., frontoparietal, default mode networks), as in previous work [41, 50, 51]. To aid mechanistic understanding, the anatomy of identified impulsivity and neuroticism networks is further summarized separately for positive and negative predictive edges. Positive edges, together hereafter referred to as a positive network, comprise connections for which increased functional connectivity tracks increased trait score; whereas a negative network comprises connections for which decreased functional connectivity tracks increased trait score. Note that, while a single connection cannot be both a positive and a negative predictor, a given canonical neural network (e.g., default mode network) may contain both positive and negative predictive connections.

To further maximize mechanistic insight, we also employed a post-hoc virtual lesioning approach, in which we lesion connections overlapping with all but a single canonical network (e.g., default mode) and rerun CPMs to determine the relative importance of the connections within each of these established networks alone in predicting a given behavioral measure (i.e., impulsivity or neuroticism). Finally, we also explored the anatomical overlap across identified impulsivity and neuroticism networks—both with one another and in relation to the previously identified alcohol-use risk network [30].

External replication using the data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD study)

To test the external validity of our findings, we asked whether the identified neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism can also predict behavioral measures associated with impulsivity and neuroticism in an independent sample using a subset of participants in the ABCD study [52] (as made available in Release 3.0). Raw data were downloaded and analyzed using our advanced connectivity pipeline as part of ongoing work with Yale’s Magnetic Resonance Research Center (MRRC). We analyzed functional connectivity data acquired during SST task performance collected during the second timepoint of fMRI scanning, corresponding to when participants were ~11-12 years of age. As pre-processing of this sample remains ongoing, a total of ~1339 participants were included in the present analysis, following the pre-processing pipeline outlined above and in a previous study [53] (see Supplemental Information for quality control/date inclusion criteria). As neither the SURPS or the NEO are included in ABCD, our primary behavioral variables of interest are the five distinct facets of impulsivity in the well-validated UPPS Impulsive Behavioral Scale [54], and the summary score for anxiety disorder from the Children Behavioral Checklist (CBCL) [55].

Results

Cross-validated CPM analysis reveals consistent and generalizable brain-behavior associations

CPM models were successful in identifying neural networks predictive of both impulsivity and neuroticism, as determined via permutation testing (impulsivity: r = 0.19, p < 0.001; neuroticism: r = 0.17, p < 0.001). Sex-specific CPM models were also successful (impulsivityfemale: r = 0.21, p < 0.001; impulsivitymale: r = 0.17, p < 0.001; neuroticismfemale: r = 0.14, p = 0.001; neuroticismmale: r = 0.20, p < 0.001) and further generalized to cross-predict across sex (i.e., connections predicting female impulsivity generalized to predict male impulsivity and vice versa; details in Supplementary Analysis 1), indicating shared anatomy across males and females. As such, for the remaining analyses we focused on neural networks identified using the female and male combined data. In addition, we also found comparable CPM prediction accuracy (impulsivity: r = 0.17, p < 0.001; neuroticism: r = 0.16, p < 0.001) and similar anatomy of the neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism (see Supplemental Analysis 2) in separate leave-one-site-out cross-validated CPMs for impulsivity and neuroticism, indicating the resulting patterns observed are not driven by site differences. Finally, we also ran separate CPMs using partial correlation controlling for mean framewise displacement for impulsivity and neuroticism, and again found comparable CPM prediction accuracy (impulsivity: r = 0.18; neuroticism: r = 0.16) and similar anatomy of the neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism (see Supplemental Analysis 3), ruling out the motion as a potential confound for our findings.

Network anatomy

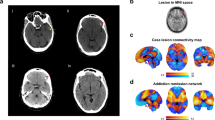

Connections consistently identified in 75% vs 100% of CPM repeats were similar, though those identified in 100% of repeats were fewer (as expected). Given our focus on elucidating neural mechanisms, we focus below on the anatomy identified in 75% of the models (see Supplementary Analysis 4 for details on 100%). As seen in Fig. 2.a.i-ii., the neural connections subserving impulsivity were predominantly related to the motor/sensory network. Specifically, impulsivity was positively predicted by connections within the motor/sensory network and between the motor/sensory and medial frontal network, and negatively predicted by connections between the motor/sensory network and other canonical networks, specifically the frontoparietal, cerebellar and subcortical networks. A further examination of the neuroanatomy at the node level revealed that nodes from the primary motor cortex, primary somatosensory cortex, and premotor and supplementary motor cortex were among the nodes within the motor/sensory network with the highest number of connecting edges.

i-ii, Positive and negative networks that predict (a) impulsivity and (b) neuroticism. A positive network denotes the connections for which increased functional connectivity predicts an increase of a given behavioral trait; a negative network denotes the connections for which decreased functional connectivity predicts an increase of a given behavioral trait. Impulsivity is mainly predicted by positive connections within the motor/sensory network, and negative connections between motor/sensory and other canonical networks. By contrast, the functional connections that predict neuroticism were much more distributed throughout canonical networks. iii, We ran a virtual lesioning analysis by removing functional connections overlapping with all but a single canonical network and reran CPM iteratively to compare the relative importance of the canonical networks in prediction accuracy for each trait. The functional connections overlapping with the motor/sensory network alone result in similar CPM prediction accuracy for impulsivity (relative to CPM using whole-brain connectivity); the functional connections overlapping with the frontoparietal and the subcortical networks alone result in similar CPM prediction accuracy for neuroticism (relative to CPM using whole-brain connectivity); and using the functional connections overlapping with other networks show a diminished—but only to a relatively small extent— prediction accuracy.

In contrast to the impulsivity network, the identified functional connectivity signature of neuroticism, shown in Fig. 2.b.i-ii, was relatively more distributed across multiple canonical neural networks. Some of the major connections that positively predicted neuroticism included within motor/sensory network connections, connections between the default mode and frontoparietal networks, between subcortical and frontoparietal networks, and between the cerebellar and subcortical networks. The major connections that negatively predicted neuroticism were between motor/sensory and default mode networks, and between motor/sensory and subcortical networks. A further examination of the neuroanatomy at the node level revealed that nodes from the thalamus, hippocampus, cerebellum and insula were among the highest degree nodes. Together, our findings suggest that the functional connectivity signature of impulsivity is predominantly localized to functional connections involving the motor/sensory network, whereas the functional connectivity signature of neuroticism is relatively more distributed across canonical networks.

Using post-hoc virtual lesioning to determine the relative importance of connections in these canonical networks as functional connectivity signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism

Having characterized the functional connectivity signature of impulsivity and neuroticism, we next conducted a post-hoc virtual lesioning analysis to: (1) test whether the motor/sensory network was in fact central for predicting impulsivity, and (2) elucidate the relative importance of other canonical networks as functional connectivity signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism. As shown in Fig. 2.a.iii, we found that using only the functional connections overlapping with the motor/sensory network resulted in similar accuracy for impulsivity—but that using connections for any other network alone reduced overall accuracy—thereby, validating the centrality of motor/sensory network connections to the identified functional connectivity signature of impulsivity. On the other hand, for neuroticism, post-hoc virtual lesion analysis revealed that using only the functional connections overlapping with the frontoparietal and subcortical networks resulted in similar prediction accuracy for neuroticism, whereas using connections from other networks showed a diminished—but only to a relatively small extent— prediction accuracy. This contrast between the post-hoc lesioning results of impulsivity and neuroticism further confirmed that the functional connectivity signature of neuroticism is relatively more distributed across canonical networks.

Do impulsivity and neuroticism share common neural signatures?

We first tested for a correlation between behavioral measures of impulsivity and neuroticism. We found a significant correlation between the two traits (r = 0.26, p < 0.001). Next, to directly investigate whether impulsivity and neuroticism share any common neural circuits, we tested for unique versus shared neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism. Interestingly, we found only 66 edges—which corresponded to 2.7% of the total edges in the impulsivity network (total: 2424 edges) and 4.0% in the neuroticism network (total: 1620 edges)—that were common between these two core behavioral traits (Fig. 3a). To better understand these shared edges and gain insights into the potential neurobiological overlap between these two traits, we next characterized the anatomy of these shared edges, and investigated their directionality (i.e., positive or negative predictor) in predicting impulsivity and neuroticism. As shown in Fig. 3b, the shared connections were mostly centralized to connections within the motor/sensory network, between motor/sensory and subcortical networks, and between motor/sensory and the cerebellar networks. Next, considering the predictive directionality of these shared edges for impulsivity and neuroticism (Fig. 3c), we found that only half of the shared connections predicted impulsivity and neuroticism in the same direction. Finally, we also tested the possibility that the neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism may nonetheless cross-predict behavioral measures of the other trait despite not overlapping: they did not (predicting impulsivity with neuroticism signatures: r = −0.004, p = 0.88; predicting neuroticism with impulsivity signatures: r = 0.008, p = 0.77), indicating that the neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism are distinct from each other. As a further confirmation of these findings and to test whether the observed network separation might be dependent on our a priori feature selection threshold, we repeated CPMs using different, more liberal thresholds. Regardless of the threshold, the overall anatomy of each network remained relatively consistent and, most importantly, the networks did not cross-predict (all p’s > 0.7), providing further evidence that the core anatomy of impulsivity and neuroticism networks are largely distinct from one another (see Supplementary Analysis 5 for additional details).

a The shared vs. unique connections that predict impulsivity and neuroticism, as represented in a Venn diagram. b The shared connections between impulsivity and neuroticism, summarized by connectivity between large-scale canonical networks. c The overlap of shared connections between impulsivity and neuroticism, as separated by positive and negative networks.

Do neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism overlap with a previously identified alcohol-use risk network?

To test whether impulsivity and neuroticism are indeed closely associated with alcohol-use risk in this specific sample of participants on a behavioral level, we first tested for a correlation between the behavioral measures of impulsivity and neuroticism with a well-validated self-report measure of alcohol-use risk—the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [38, 39]. Consistent with findings in the literature, we found a significant correlation between participants’ AUDIT scores and impulsivity (r = 0.21, p < 0.0001), and neuroticism (r = 0.08, p = 0.004), respectively, indicating that elevated rates of impulsivity and neuroticism are both linked to alcohol-use risk in this sample of youth on a behavioral level.

Next, to test whether the functional connectivity signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism overlap with a previously identified neural network implicated in alcohol-use risk [30], we characterized the shared connections among the impulsivity, neuroticism, and alcohol-use risk networks, and investigated the directionality of these shared edges in predicting impulsivity and neuroticism versus alcohol-use risk. As seen in Fig. 4a, we observed the impulsivity and neuroticism networks overlap with the alcohol-use risk network via distinct functional connections. Within the impulsivity network, 11.6% of edges (281 out of 2424 total edges) were shared with the alcohol-use risk network (see Fig. 4b for the anatomy of the shared connections). Within the neuroticism network, 18.1% of edges (294 out of 1620 total edges) were shared with the alcohol-use risk network. Furthermore, out of the 66 edges previously identified as common to both impulsivity and neuroticism signatures and shown in Fig. 3, only 10 overlapped with the alcohol-use risk network, providing further evidence that the co-occurrence of these two traits as risk factors for alcohol misuse is likely due to largely dissociable neural mechanisms.

a The shared vs. unique connections that predict impulsivity, neuroticism and alcohol-use risk, as represented in a Venn diagram. Impulsivity and neuroticism overlap with the alcohol-use risk network via distinct functional connections. b The shared connections summarized by connectivity between large-scale canonical networks. c The overlap of shared connections, as separated by positive and negative networks. The edges in the impulsivity (blue) and neuroticism (yellow) networks that distinctively overlap with the alcohol-use risk network mostly predict the trait and alcohol-use in the same direction. Very few edges are found to consistently predict impulsivity, neuroticism, and alcohol-use in the same direction (purple), suggesting unique contributions of each trait to alcohol-use risk.

Finally, we also examined the predictive directionality of these shared edges for impulsivity and neuroticism versus alcohol-use risk networks. As shown in Fig. 4c, the shared connections that positively predict impulsivity also mostly positively predict the alcohol-use risk (173 out of 175 edges), and the shared connections that negatively predict impulsivity also mostly negatively predict the alcohol-use risk (100 out of 106 edges), consistent with impulsivity being a known positive predictor of alcohol misuse. Similarly, the shared connections that positively predict neuroticism also mostly positively predict the alcohol-use risk (143 out of 145 edges), and the shared connections that negatively predict neuroticism all negatively predict alcohol-use risk (149 total edges), also consistent with neuroticism being a known positive predictor of alcohol misuse.

External validation using data from the ABCD study

The ultimate test of generalizability is whether neural signatures identified in one study can generalize to predict in an independent sample with characteristics different from those of the original sample. As such, we asked whether the identified neural signatures may also predict impulsivity- and neuroticism-related measures in a subset of participants from the ABCD study. There are several key differences between the ABCD and IMAGEN participants, including geographic location (North America vs. Europe), age (~11-12 vs. 19), a more diverse demographic make-up of participants in ABCD, different imaging acquisition parameters and different assessments of impulsivity- and neuroticism-related traits.

Despite these wide differences, we nevertheless found significant (yet modest) associations between connectivity strength within the impulsivity and neuroticism networks identified above and impulsivity and neuroticism measures, respectively, among individuals in the ABCD study (impulsivity: r = 0.054, p = 0.049; neuroticism: r = 0.067, p = 0.014). To confirm specificity, we tested the ability of each network to also cross-predict in ABCD (e.g., can the impulsivity network predict neuroticism?). Neither network cross-predicted the other trait (impulsivity network: r = 0.016, p = 0.57); neuroticism network: r = −0.02, p = 0.43).

Discussion

This study for the first time identified functional connectivity signatures of two common risk factors for alcohol-use in youth—impulsivity and neuroticism—and assessed their anatomical overlap with a previously identified signature of alcohol-use risk [30]. Consistent with current equifinality-based conceptions of development [56], we identified very few connections that predicted both impulsivity and neuroticism, indicating that the neural signatures of these two traits are relatively distinct despite their co-predicting alcohol misuse and a wide array of psychiatric illnesses. For each trait, approximately 10-20% of connections overlapped with the alcohol-use risk network; however, these shared connections were largely distinct between the two traits, indicating dissociable anatomical contributions to alcohol misuse in youth.

Consistent with classic models focusing on inhibitory ‘top-down’ and subcortical ‘bottom-up’ developmental networks [32, 33], the frontoparietal and subcortical networks were implicated in the neural signature of impulsivity via decreased connectivity with the motor/sensory network. Interestingly, we also observed decreased connectivity between the motor/sensory and the cerebellar networks and increased connectivity within the motor/sensory network as key features of the neural signature of impulsivity. The former observation is consistent with growing evidence for the association between cerebellar abnormalities and impulsivity-related neuropsychiatric disorders, including addictions [27, 57, 58]. Moreover, the overall relevance of the motor/sensory network for impulsivity complements recent findings in adults indicating involvement of motor/sensory networks in impulsivity [34, 59] and are further consistent with work demonstrating that individual differences in motor/sensory network functional connections are prospectively linked to treatment outcomes among individuals with substance use disorders [40, 44]. Our work extends this prior work by validating the importance of the motor/sensory network for impulsivity in a large sample of adolescents, providing further evidence that the motor/sensory network is implicated in impulsivity across samples and age. These findings are further consistent with recent evidence for a somato-cognitive action network within the motor cortex that integrates goals, physiology and body movement for whole-body action planning [60], highlighting the relevance of the motor/sensory network for action planning beyond somatosensation and the execution of fine movement control.

Relative to the impulsivity network, the neuroticism network was more widely distributed across canonical networks, consistent with previous findings linking increases in neuroticism to alterations within diverse white-matter microstructures [61] and altered brain-wide functional network organization [62] in smaller samples of adults. In addition, our findings for the association between neuroticism and functional connections associated with motor/sensory, subcortical and cerebellum networks are consistent with a previous report on these networks predicting neuroticism in adults [63], and suggest that the neural correlates of neuroticism may therefore be generalizable across samples and age. In addition, consistent with the known association between neuroticism and neural processing of salient affective stimuli and emotions [3, 62], we also observed a high number of edges with significant associations with neuroticism in the insula, thalamus, hippocampus, and the cerebellum.

Despite impulsivity and neuroticism co-predicting a wide range of psychopathology, we found few shared functional connections between the two traits, indicating that the neurobiological basis for these two traits is largely dissociable. These findings are not surprising given prior literature on impulsivity and neuroticism as distinctively associated with externalizing and internalizing psychopathologies [64, 65], respectively, which are classically considered to be distinct pathways to substance use behaviors in youth. Moreover, coupled with our findings that impulsivity and neuroticism each differentially shared approximately 10% overlap with the alcohol-use risk network, our findings provide neurobiological evidence for the longstanding developmental concept of equifinality—i.e., that diverse pathways may lead to the same outcome [56]. Finally, these results raise the possibility that the co-occurrence of these two traits might have a problematic additive effect at the neurodevelopmental level to increase alcohol misuse during adolescence, consistent with findings that negative urgency—the disposition to engage in rash action when experiencing strong negative affects [66]— is highly related to drinking problems and alcohol dependence [19, 67].

Given impulsivity and neuroticism share little neurobiological overlap, why then might they nevertheless share a significant correlation of behavioral measures and often co-predict a wide range of psychopathology? An examination of the shared connections between each trait and the alcohol use network revealed that the connections shared between impulsivity and alcohol-use were predominantly within motor/sensory, motor/sensory to frontoparietal and motor/sensory to cerebellar, whereas connections shared between neuroticism and alcohol-use were predominantly motor/sensory to default mode, motor/sensory to subcortical, and subcortical to cerebellar. These findings highlighted the relevance of motor/sensory connectivity in the overlap between the alcohol use risk network and each of the traits. Building on previous work on the role of motor/sensory connectivity in multiple dimensional (and likely transdiagnostic) mechanisms of psychopathology [34], one possibility is that motor/sensory connectivity might underlie a person’s general liability for psychiatric disorders [68].

Why do only approximately 10% of functional connections that make up the impulsivity and neuroticism signatures overlap with the alcohol-use risk network? One possible reason is that impulsivity and neuroticism are known to be multidimensional constructs, and their distinct dimensions are said to be differently associated with alcohol misuse [67]; however, in this study, we used a single composite measure for each trait, hence, our analysis could only identify the functional connections that are associated with the broader construct of impulsivity and neuroticism, and might have missed out on the functional connections that are unique to specific facets of a trait. Another possible and not mutually exclusive reason is that, beyond impulsivity and neuroticism, there are many other risk factors of alcohol misuse, including genetic, sociodemographic, family and cultural factors, and their neural signatures likely also overlap with the alcohol risk network. Future research on the functional connectivity signatures of the other risk factors and their overlap with the alcohol risk network may elucidate the neurobiological interactions of multiple levels of risk factors for alcohol misuse.

We note that, even though we were able to externally replicate the impulsivity and neuroticism network, the replication effects were nevertheless quite small. Beyond the sociodemographic and data acquisition differences between the two samples, another relevant factor is that the ABCD sample (age ~11-12) is much younger than the IMAGEN sample (age 19), and these behavioral traits and the associated networks have yet to be fully developed in the ABCD sample. Moreover, at the age of 11-12, the rate of alcohol use is also very low in ABCD; thus, we were unable to test whether our prior alcohol-use risk signature extended to the ABCD sample (though our prior work did validate the alcohol-risk signature in a different independent, non-IMAGEN sample) [30]. To further validate these networks and examine their changes across development and in relationship to the onset of alcohol use, one key future direction will be to track the longitudinal changes of these networks in the future release of ABCD.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

This study has multiple strengths, including the well-powered sample of >1000 individuals and external replication of primary findings in an independent cohort of youth from the ABCD study. However, several limitations should be noted. First, most participants in IMAGEN (and to a lesser extent in ABCD) are of White European ancestry, and we did not test for the potential effect of socioeconomic status; thus, it remains to be determined whether our findings could be generalized to more diverse populations. Second, all assessments of impulsivity and neuroticism were questionnaire-based. Thus, the extent to which these findings would extend to more nuanced behavioral and/or clinician-administered assessments remains to be determined. Third, our networks were identified during the SST task, thus it remains unknown whether the networks may generalize to the resting state, in which participants are not engaged in motor tasks. Finally, given the cross-sectional design of the analysis, our study is not suited to inform temporal relationships among impulsivity, neuroticism, and alcohol use. These data nonetheless for the first time identify largely dissociable neural signatures of impulsivity and neuroticism during adolescence, and elucidate the potential neural basis of the interaction among alcohol-use risk, impulsivity, and neuroticism in youth. Future data releases of ABCD will enable extension of these findings longitudinally and with respect to alcohol-use onset. These findings may shed light on neural mechanisms of impulsivity, neuroticism and the prototypical risky behavior of alcohol use in youth. It should nonetheless be noted that these predictive markers are not intended for clinical use at this stage. Rather, our aim in conducting this work is to provide elucidation of mechanism that may inform development of improved prevention and intervention strategies grounded in known neurobiology [69].

Data availability

The IMAGEN Consortium does not share individual patient data. The identified impulsivity and neuroticism networks are available at https://github.com/YaleYipLab.

Code availability

The scripts for running Connectome Based Predictive Modeling are available at https://www.nitrc.org/projects/bioimagesuite.

References

Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Fractionating impulsivity: neuropsychiatric implications. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:158–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.8.

Widiger TA, Oltmanns JR. Neuroticism is a fundamental domain of personality with enormous public health implications. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:144–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20411.

Lin J, Li L, Pan N, Liu X, Zhang X, Suo X, et al. Neural correlates of neuroticism: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of resting-state functional brain imaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023;146:105055 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105055.

Kozak K, Lucatch AM, Lowe DJE, Balodis IM, MacKillop J, George TP. The neurobiology of impulsivity and substance use disorders: implications for treatment. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 2019;1451:71–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13977.

Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. OPINION Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2513.

Tapert SF, Eberson-Shumate S. Alcohol and the adolescent brain: what we’ve learned and where the data are taking us. Alcohol Res-Curr Rev. 2022;42:07.

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Inst Soc Res. 2016.

Squeglia LM, Gray KM. Alcohol and drug use and the developing brain. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18:46 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0689-y.

Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Hawkins J, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2015. Morbidity Mortal Wkly Report: Surveill Summaries. 2016;65:1–174.

Stautz K, Cooper A. Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:574–92.

Shin SH, Hong HG, Jeon S-M. Personality and alcohol use: the role of impulsivity. Addict Behav. 2012;37:102–7.

Mushquash CJ, Stewart SH, Mushquash AR, Comeau MN, McGrath PJ. Personality traits and drinking motives predict alcohol misuse among Canadian aboriginal youth. Int J Ment Health Addiction. 2014;12:270–82.

Jackson KM, Sher KJ. Alcohol use disorders and psychological distress: a prospective state-trait analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:599.

Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:360.

Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, van den Brink W, Smit JH, Beekman AT, Penninx BW. The role of negative emotionality and impulsivity in depressive/anxiety disorders and alcohol dependence. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1241–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712002152.

Zilberman N, Yadid G, Efrati Y, Neumark Y, Rassovsky Y. Personality profiles of substance and behavioral addictions. Addict Behav. 2018;82:174–81.

Herman AM, Duka T. Facets of impulsivity and alcohol use: What role do emotions play? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;106:202–16.

Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:719–59.

Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Karyadi KA, Koo C, Cyders MA. Mechanisms underlying the relationship between negative affectivity and problematic alcohol use. J Exp Psychopathol. 2013;4:263–78.

Creswell KG. Drinking together and drinking alone: a social-contextual framework for examining risk for alcohol use disorder. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2021;30:19–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420969406.

Gonzalez VM, Skewes MC. Solitary heavy drinking, social relationships, and negative mood regulation in college drinkers. Addiction Res Theory. 2013;21:285–94.

Bilevicius E, Single A, Rapinda KK, Bristow LA, Keough MT. Frequent solitary drinking mediates the associations between negative affect and harmful drinking in emerging adults. Addict Behav. 2018;87:115–21.

Conner KR, Pinquart M, Gamble SA. Meta-analysis of depression and substance use among individuals with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:127–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.007.

Keough MT, O’Connor RM, Sherry SB, Stewart SH. Context counts: solitary drinking explains the association between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. Addict Behav. 2015;42:216–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.031.

Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:149–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00027-6.

Yip SW, Potenza MN. Application of Research Domain Criteria to childhood and adolescent impulsive and addictive disorders: Implications for treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;64:41–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.11.003.

Yip SW, Worhunsky PD, Xu J, Morie KP, Constable RT, Malison RT, et al. Gray-matter relationships to diagnostic and transdiagnostic features of drug and behavioral addictions. Addict Biol. 2018;23:394–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12492.

Chambers RA, Taylor J, Potenza M. Developmental neurocircuitry of motivation in adolescence: a critical period of addiction vulnerability. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1041–52.

Etkin A, Buchel C, Gross JJ. The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:693–700. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn4044.

Yip SW, Lichenstein SD, Liang QH, Chaarani B, Dager A, Pearlson G, et al. Brain networks and adolescent alcohol use. JAMA Psychiat. 2023;80:1131–41. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.2949.

Dhamala E, Rong Ooi LQ, Chen J, Ricard JA, Berkeley E, Chopra S, et al. Brain-based predictions of psychiatric illness-linked behaviors across the sexes. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;94:479–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2023.03.025.

Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev Rev. 2008;28:78–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002.

Somerville LH, Jones RM, Casey B. A time of change: behavioral and neural correlates of adolescent sensitivity to appetitive and aversive environmental cues. Brain Cognition. 2010;72:124–33.

Kebets V, Holmes AJ, Orban C, Tang SY, Li JW, Sun NB, et al. Somatosensory-motor dysconnectivity spans multiple transdiagnostic dimensions of psychopathology. Biol Psychiat. 2019;86:779–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.06.013.

Schumann G, Loth E, Banaschewski T, Barbot A, Barker G, Büchel C, et al. The IMAGEN study: reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology. Mol Psychiatr. 2010;15:1128–39. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2010.4.

Woicik PA, Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Conrod PJ. The substance use risk profile scale: A scale measuring traits linked to reinforcement-specific substance use profiles. Addict Behav. 2009;34:1042–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.07.001.

Costa PT, McCrae RR, Psychological Assessment Resources, I. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI). Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992.

Babor TF, World Health, O. AUDIT : the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: guidelines for use in primary health care. World Health Organization; 1992.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x.

Yip SW, Scheinost D, Potenza MN, Carroll KM. Connectome-based prediction of cocaine abstinence. Am J Psychiat. 2019;176:156–64. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101147.

Finn ES, Shen X, Scheinost D, Rosenberg MD, Huang J, Chun MM, et al. Functional connectome fingerprinting: identifying individuals using patterns of brain connectivity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1664–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4135.

Rosenberg MD, Finn ES, Scheinost D, Papademetris X, Shen X, Constable RT, et al. A neuromarker of sustained attention from whole-brain functional connectivity. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:165–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4179.

Rosenberg MD, Zhang S, Hsu WT, Scheinost D, Finn ES, Shen X, et al. Methylphenidate modulates functional network connectivity to enhance attention. J Neurosci. 2016;36:9547–57. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1746-16.2016.

Lichenstein SD, Scheinost D, Potenza MN, Carroll KM, Yip SW. Dissociable neural substrates of opioid and cocaine use identified via connectome-based modelling. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:4383–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0586-y.

Greene AS, Shen X, Noble S, Horien C, Hahn CA, Arora J, et al. Brain-phenotype models fail for individuals who defy sample stereotypes. Nature. 2022;609:109–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05118-w.

Greene AS, Gao S, Scheinost D, Constable RT. Task-induced brain state manipulation improves prediction of individual traits. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2807 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04920-3.

Shen X, Tokoglu F, Papademetris X, Constable RT. Groupwise whole-brain parcellation from resting-state fMRI data for network node identification. Neuroimage. 2013;82:403–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.081.

Scheinost D, Noble S, Horien C, Greene AS, Lake EM, Salehi M, et al. Ten simple rules for predictive modeling of individual differences in neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 2019;193:35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.02.057.

Kong X-z, Zhen Z, Li X, Lu H-h, Wang R, Liu L, et al. Individual differences in impulsivity predict head motion during magnetic resonance imaging. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104989.

Noble S, Spann MN, Tokoglu F, Shen X, Constable RT, Scheinost D. Influences on the test–retest reliability of functional connectivity MRI and its relationship with behavioral utility. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27:5415–29.

Horien C, Shen X, Scheinost D, Constable RT. The individual functional connectome is unique and stable over months to years. Neuroimage. 2019;189:676–87.

Garavan H, Bartsch H, Conway K, Decastro A, Goldstein RZ, Heeringa S, et al. Recruiting the ABCD sample: Design considerations and procedures. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.004.

Rapuano KM, Rosenberg MD, Maza MT, Dennis NJ, Dorji M, Greene AS, et al. Behavioral and brain signatures of substance use vulnerability in childhood. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2020;46:100878 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100878.

Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Indiv Differ. 2001;30:669–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7.

Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM. The Child Behavior Checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:265–71. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.21-8-265.

Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol. 1996;8:597–600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400007318.

Miquel M, Nicola SM, Gil-Miravet I, Guarque-Chabrera J, Sanchez-Hernandez A. A working hypothesis for the role of the cerebellum in impulsivity and compulsivity. Front Behav Neurosci. 2019;13:99.

Yip SW, Lichenstein SD, Garrison K, Averill CL, Viswanath H, Salas R, et al. Effects of smoking status and state on intrinsic connectivity. Biol Psychiatry: Cognit Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021;7:895–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2021.02.004.

Cai H, Chen J, Liu S, Zhu J, Yu Y. Brain functional connectome-based prediction of individual decision impulsivity. Cortex. 2020;125:288–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.01.022.

Gordon EM, Chauvin RJ, Van AN, Rajesh A, Nielsen A, Newbold DJ, et al. A somato-cognitive action network alternates with effector regions in motor cortex. Nature. 2023;617:351–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-05964-2.

Bjornebekk A, Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Grydeland H, Torgersen S, Westlye LT. Neuronal correlates of the five factor model (FFM) of human personality: Multimodal imaging in a large healthy sample. Neuroimage. 2013;65:194–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.009.

Servaas MN, Geerligs L, Renken RJ, Marsman JB, Ormel J, Riese H, et al. Connectomics and neuroticism: an altered functional network organization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:296–304. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.169.

Hsu WT, Rosenberg MD, Scheinost D, Constable RT, Chun MM. Resting-state functional connectivity predicts neuroticism and extraversion in novel individuals. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2018;13:224–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsy002.

Beauchaine TP, Zisner AR, Sauder CL. Trait Impulsivity and the Externalizing Spectrum. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2017;13:343–68. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093253.

Griffith JW, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Rose RD, Waters AM, et al. Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1125–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709991449.

Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bull. 2008;134:807.

Coskunpinar A, Dir AL, Cyders MA. Multidimensionality in impulsivity and alcohol use: a meta‐analysis using the UPPS model of impulsivity. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1441–50.

Caspi A, Moffitt TE. All for one and one for all: Mental disorders in one dimension. Am J Psychiat. 2018;175:831–44.

Yip SW, Kiluk B, Scheinost D. Toward addiction prediction: an overview of cross-validated predictive modeling findings and considerations for future neuroimaging research. Biol Psychiatry: Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2020;5:748–58.

Acknowledgements

This work received support from the following sources: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01AA027553, T32DA022975 (SR), National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01DA053301, National Institute of Health grant GM007205 (AG), TR001864 (AG), a postdoctoral fellowship from the Yale Center for Brain and Mind Health (MB), the European Union-funded FP6 Integrated Project IMAGEN (Reinforcement-related behaviour in normal brain function and psychopathology) (LSHM-CT- 2007-037286), the Horizon 2020 funded ERC Advanced Grant ‘STRATIFY’ (Brain network based stratification of reinforcement-related disorders) (695313), Horizon Europe ‘environMENTAL’, grant no: 101057429, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Horizon Europe funding guarantee (10041392 and 10038599), Human Brain Project (HBP SGA 2, 785907, and HBP SGA 3, 945539), the Chinese government via the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), The German Center for Mental Health (DZPG), the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF grants 01GS08152; 01EV0711; Forschungsnetz AERIAL 01EE1406A, 01EE1406B; Forschungsnetz IMAC-Mind 01GL1745B), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG project numbers 178833530 (SFB 940), 402170461 (TRR 265), 454245598 (IRTG 2773), and 521379614 (TRR 393), NE 1383/14-1, TRR379 projects B05 & Q01), in parts funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung [BMBF]) and Ministry of Science, Research and Arts of Baden-Württemberg within the German Center for Mental Health (DZPG, grants: DLR 01EE2504A, 01EE2504D, 01EE2504D), the Medical Research Foundation and Medical Research Council (grants MR/R00465X/1 and MR/S020306/1), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded ENIGMA-grants 5U54EB020403-05, 1R56AG058854-01 and U54 EB020403 as well as NIH R01DA049238, the National Institutes of Health, Science Foundation Ireland (16/ERCD/3797), NSFC grant 82150710554. Further support was provided by grants from: - the ANR (ANR-12-SAMA-0004, AAPG2019 - GeBra), the Eranet Neuron (AF12-NEUR0008-01 - WM2NA; and ANR-18-NEUR00002-01 - ADORe), the Fondation de France (00081242), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (DPA20140629802), the Mission Interministérielle de Lutte-contre-les-Drogues-et-les-Conduites-Addictives (MILDECA), the Assistance-Publique-Hôpitaux-de-Paris and INSERM (interface grant), Paris Sud University IDEX 2012, the Fondation de l’Avenir (grant AP-RM-17-013), the Fédération pour la Recherche sur le Cerveau; ImagenPathways “Understanding the Interplay between Cultural, Biological and Subjective Factors in Drug Use Pathways” is a collaborative project supported by the European Research Area Network on Illicit Drugs (ERANID). This paper is based on independent research commissioned and funded in England by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme (project ref. PR-ST-0416-10001). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the national funding agencies or ERANID.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: Cheng, Lichenstein, Yip, Garavan, Liang, Desrivières, Flor, Heinz, Nees, Smolka, Walter, Schumann. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Cheng, Yip, Lichenstein, Liang, Chaarani, Garavan, Babaeianjelodar, Riley, Luo, Horien, Greene, Pearlson, Constable, Banaschewski, Bokde, Desrivières, Flor, Grigis, Gowland, Heinz, Brühl, Martinot, Paillère Martinot, Artiges, Nees, Papadopoulos Orfanos, Poustka, Hohmann, Holz, Baeuchl, Smolka, Vaidya, Walter, Whelan, Schumann. Drafting of the manuscript: Cheng, Yip, Lichenstein. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Cheng, Yip, Lichenstein, Liang, Chaarani, Garavan, Babaeianjelodar, Riley, Luo, Horien, Greene, Pearlson, Constable, Banaschewski, Bokde, Desrivières, Flor, Grigis, Gowland, Heinz, Brühl, Martinot, Paillère Martinot, Artiges, Nees, Papadopoulos Orfanos, Poustka, Hohmann, Holz, Baeuchl, Smolka, Vaidya, Walter, Whelan, Schumann. Statistical analysis: Cheng, Yip, Lichenstein, Riley, Babaeianjelodar, Liang, Garavan. Obtained funding: Yip, Bokde, Desrivières, Flor, Heinz, Martinot, Paillère Martinot, Nees, Papadopoulos Orfanos, Smolka, Schumann. Administrative, technical, or material support: Yip, Chaarani, Bokde, Desrivières, Grigis, Gowland, Heinz, Brühl, Martinot, Nees, Papadopoulos Orfanos, Smolka, Vaidya, Walter, Whelan, Schumann. Supervision: Yip, Lichenstein, Pearlson, Flor, Schumann.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Banaschewski served in an advisory or consultancy role for AGB pharma, eye level, Infectopharm, Medice, Neurim Pharmaceuticals, Oberberg GmbH and Takeda. He received conference support or speaker’s fee by AGB pharma, Janssen-Cilag, Medice and Takeda. He received royalties from Hogrefe, Kohlhammer, CIP Medien, Oxford University Press. The present work is unrelated to the above grants and relationships. Dr Barker has received honoraria from General Electric Healthcare for teaching on scanner programming courses. Dr Poustka served in an advisory or consultancy role for Roche and Viforpharm and received speaker’s fee by Shire. She received royalties from Hogrefe, Kohlhammer and Schattauer. The present work is unrelated to the above grants and relationships. The other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, A., Lichenstein, S., Chaarani, B. et al. Impulsivity and neuroticism share distinct functional connectivity signatures with alcohol-use risk in youth. Mol Psychiatry 31, 953–962 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03196-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03196-6