Abstract

Neuroanatomical findings on panic disorder (PD) are typically difficult to replicate, with inconsistent effects. These concerns prompted a paradigm shift towards large-scale collaborations, focused on harmonized data extraction and processing for robust examination of PD brain correlates. Hence, leveraging the largest-ever multi-site neuroimaging database on PD (Age: 10–66 years; global sites: 28), compiled by the ENIGMA-Anxiety Working Group, we report on cortical and subcortical differences in individuals with PD (N = 1146) versus healthy controls (HC: N = 3778). The analyses revealed lower thickness and smaller cortical surface area within fronto-temporo-parietal regions in PD (Cohen’s ds: −0.08–0.13), along with lower thalamic and caudate volumes (Cohen’s ds: −0.07–0.12). Diagnosis-by-age2 interactions (Cohen’s ds: 0.07–0.12) revealed lower thickness in individuals with PD compared to HC in certain regions during adulthood (25–55 years), with relative absence of such differences during youth (<25 years) or late adulthood (>55 years). Finally, patient subgroup analyses showed that early disease onset (≤21 years) in PD was associated with larger lateral ventricles (Cohen’s ds: 0.31–0.38), whilst no medication, comorbidity, or severity effects were found. These findings lend support to neurocircuitry models of PD, which postulate differences within fronto-striato-limbic circuits and temporo-parietal regions. Moreover, findings highlight the potential importance of abnormal development and aging in neuroanatomical differences related to PD. Given its unprecedented scale, the current study is an important milestone towards identifying the structural brain correlates of PD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Panic disorder (PD) is a common anxiety disorder that affects adolescents, adults, and even children. The condition has a 1–2% 12-month, and a 1.7–4% lifetime prevalence [1, 2]. Diagnosis of PD involves the presence of recurrent panic attacks, alongside other debilitating symptoms and behavioral changes due to the fear of potential attacks [3, 4], leading to great personal distress. Moreover, PD is a significant public health concern linked to a multitude of adverse physical health outcomes [5]. This highlights the urgency to improve our understanding of the diagnosis and etiology of the disorder, to optimize early-intervention and treatment.

Despite almost two decades of anxiety neuroimaging research with some promising findings [6], our knowledge of the pathophysiology and underlying neurobiology of PD remains incomplete [7]. Structural neuroimaging studies of PD suggest the presence of gray matter differences within fronto-striato-limbic circuitries and additional temporo-parietal sensory regions [8,9,10], sometimes modulated by lifestyle factors [11]. More specifically, individuals with PD have been observed to exhibit both higher and lower volumes in the amygdala, hippocampus, and temporal and occipital regions, whereas lower gray matter volumes were slightly more consistently reported in the thalamus, anterior cingulate cortex, and cerebellum [12,13,14]. An overview of regions previously implicated in PD are presented in Fig. 1. These findings, however, lack robust reproducibility and typically arise from studies with small sample sizes, low statistical power, diverse analytic approaches, and marked clinical heterogeneity [7].

Anomalies within these regions tend to collectively impede how emotionally salient information is perceived, processed, and modulated. This includes brain areas involved in sensory processing (occipital cortex, fusiform gyrus, thalamus; green), emotion generation and processing (striatum, amygdala, insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; red) and emotion modulation (medial prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, subgenual/rostral anterior cingulate cortex; blue). Adapted and reprinted with permission from Wiley Periodicals, Inc.: Human Brain Mapping (Bas-Hogendam et al., [1]). Amy Amygdala, Cau, Nucleus Caudatus, Hip Hippocampus; NAcc, Nucleus Accumbens, Pa Pallidum, Pu Putamen, Tha Thalamus, CAcc Caudal Anterior Cingulate Cortex, FF Fusiform, INS Insula, LOC Lateral Occipital, MOF Medial Orbitofrontal, RAcc Rostral Anterior Cingulate Cortex, RMF Rostral Middle Frontal, SF Superior Frontal.

One recent meta-analysis combined data from eight studies with a total of 201 people with PD; this revealed converging gray matter deficits in various prefrontal brain regions, along with the insula and superior/middle temporal gyrus [12]. While encouraging, meta-analyses based on published data are typically plagued by publication bias [13], and confounded by the vastly heterogeneous analytical approaches adopted by individual studies included [14]. Overall, neuroimaging research on PD so far has had important limitations that preclude a robust understanding of its underlying neurobiology.

To address these limitations, large-scale collaborations have been initiated, focused on the harmonization of data preprocessing and standardization of analyses. The Enhancing Neuro-Imaging Genetics Through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA) consortium is an example of such a global effort [14], and the current study is from the PD subgroup within the greater ENIGMA-Anxiety Working Group [7, 15]. The large-scale and inclusive nature of ENIGMA studies, in terms of populations, sample sizes, research centers, and data diversity, has proven critical in pinpointing robust structural brain correlates of psychopathology [14]. Hence, through the ENIGMA consortium, we performed the largest-ever coordinated investigation of cortical and subcortical neuroanatomy in people with PD (N = 1146) versus healthy controls (HC) (N = 3778), gathered from 28 international cohorts (45 global sites). Based on prior work, we expected individuals with PD to show neuroanatomical differences within the fronto-striato-limbic and temporo-parietal regions, particularly characterized by lower/smaller morphometry in the temporal, orbitofrontal, and prefrontal brain areas. Exploratory analyses further examined the potential modulating effects of key demographic (e.g., age, sex) and clinical (e.g., age of onset, medication use, severity, comorbidity) characteristics on cortical and subcortical neuroanatomy.

Methods

Participants

This analysis included neuroimaging data from 28 international studies, with clinical data from people with a lifetime and/or current DSM-IV or DSM-5 PD diagnosis and HC (i.e., free from psychopathology and psychotropic medication). A more detailed overview of the sample information is reported elsewhere [7]. In line with prior ENIGMA Anxiety studies [16, 17], diagnostic interviews (SCID, CIDI) were used to ascertain the presence or absence of PD diagnosis and other psychiatric disorders (e.g., social anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, major depressive disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorder). Individuals were excluded if they showed any MRI contra-indications (e.g., metal implants, pacemakers, claustrophobia, pregnancy) or had any history of severe neurological (e.g., seizures, stroke, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury) or medical disorders. In line with prior ENIGMA Anxiety work [16, 17], exclusion criteria for PD patients also included comorbid schizophrenia (or schizophrenia spectrum disorder), bipolar disorder, and autism spectrum disorder. Exclusion criteria for HCs were lifetime major psychiatric diagnoses and psychotropic medication use at the time of scan. Clinical information for additional analyses included symptom age of onset, psychotropic medication use at time of scan, current or lifetime presence of comorbid anxiety disorders (i.e., social anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, general anxiety disorder, specific phobia), comorbid MDD and clinical severity as measured by the Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI), the trait anxiety subscale from the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI_T; measuring “individual differences in anxiety proneness” and probes how individuals “generally feel” versus the STAI-S that indicates how individuals “feel right now, at this moment”) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI). Each study contributed clinical severity data subject to availability (see Supplement for more information). All study participants provided written informed consent and the local institutional review boards permitted the use of measures extracted from the data.

Image acquisition and processing

Structural T1-weighted brain MRI scans were acquired and processed locally at each site using standardized ENIGMA protocols for harmonization of analysis and quality control (see http://enigma.ini.usc.edu/protocols/imaging-protocols/). Regional subcortical volume (SV), cortical surface area (SA) and mean cortical thickness (CT) were extracted from the brain images using FreeSurfer software version 5.3 [16]. For each subject, SA and mean CT was calculated for 68 cortical Desikan-Killiany atlas-based regions (34 per hemisphere) and two global hemisphere measures [17]. In addition, SV was extracted for seven structures per hemisphere (accumbens, putamen, pallidum, caudate, thalamus, amygdala, and hippocampus), along with lateral ventricle and total intracranial volume (ICV). Parcellations and segmentations were visually inspected and statistically evaluated for outliers (see Supplement for details).

Statistical analysis of cortical and subcortical neuroanatomy: primary analysis

Individual-level participant data was assessed using linear mixed-effects (LME) models on the pooled cortical and subcortical neuroanatomical features from all scanning sites. Each SV, cortical SA and CT served as the outcome measure (separately for the left and right hemisphere) and a binary indicator of diagnosis (PD vs.HC) as the main predictor of interest. Age, sex, and ICV were used as additional fixed factors and site (i.e., scanner/location/study) was included as a random effect intercept (Uj) to account for effective clustering within scanning sites. Given that structural brain development follows nonlinear trajectories from childhood to adulthood [18, 19], a nonlinear expansion of age (age2) was also included as a fixed factor, in line with prior ENIGMA work [20, 21]. As we did not have specific hypotheses or expectations for potential cubic relationships between age and morphological measures, cubic age expansion terms were not included in the analyses. All LME analyses were performed in R studio (v4.0.3) using the lme4 package (v1.1-27.1). We first examined case-control differences between people with PD and HC:

-

1.

ROIij = intercept + β1(diagnosis) + β2(sex) + β3(age) + β4(age2) + β5(ICV) + Uj + εij

We then tested higher-order interactions (diagnosis-by-age, diagnosis-by-age2 and diagnosis-by-sex) by adding a multiplicative predictor as factor of interest, while including the main effect of each predictor in the model. Each dependent measure of the ith individual at jth scanning site was modeled as follows:

-

2.

ROIij = intercept + β1(diagnosis) + β2(sex) + β3(age) + β4(age2) + β5(diagnosis × age) + Uj + εij

-

3.

ROIij = intercept + β1(diagnosis) + β2(sex) + β3(age) + β4(age2) + β5(diagnosis × age2) + Uj + εij

-

4.

ROIij = intercept + β1(diagnosis) + β2(sex) + β3(age) + β4(age2) + β5(diagnosis × sex) + Uj + εij

As per prior ENIGMA work (e.g., [18, 19]), ICV was omitted from models with CT as outcome, as previous research has shown that thickness, unlike SA and SV, does not scale with head size [20]. All models required data from N ≥ 5 sites and were fit using the restricted maximum likelihood method (REML). Effect size estimates were calculated with the Cohen’s d-statistic appropriate for mixed effect models, and were computed using the t-statistic for the factor diagnosis in the fitted LME model [21]. Percent difference between cases and controls was calculated with least-squares group means using the emmeans package (v1.6.3). The Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) was used to control for multiple comparisons within each model, with p-values adjusted separately for each modality (CT, SA, and SV). Results were considered significant if the FDR-corrected p-value (q) was < 0.05.

Exploratory subgroup analyses

To investigate whether various clinical differences within the PD group were differentially associated with structural brain morphology, we conducted stratified analyses. We compared patient subgroups based on several factors: current versus lifetime diagnosis of PD, psychotropic medication use (any use or Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors [SSRIs]/Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors [SSNRIs] use), current and/or lifetime comorbid anxiety disorders (i.e., generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia, agoraphobia), comorbid depression, and PD age of onset (categorized as early ≤ 21 years or late > 21 years, in line with prior ENIGMA studies [22, 23]). We also used separate LME regression models to investigate patient-specific dimensional associations between the cortical and subcortical structures and several measures of clinical anxiety severity. For these models, each of the continuous clinical variables (i.e., ASI, STAI_T and BAI scores) replaced diagnosis as the predictor of interest in the LME formula, and the partial-correlation Pearson’s r-statistic appropriate for mixed-effects models [21] – adjusted for age, age2, sex, site, and ICV – was used to report effect size estimates. Not every cohort had each FreeSurfer modality available (i.e., SA/CT/SV) and individual values were excluded if they did not pass quality control. Specifically, cortical parcellations (SA/CT) were unavailable for 411 participants (47% of whom had PD) from 5 datasets (11.1% of the total number of datasets). For each LME model and region separately, participants were excluded if any of the variables were missing. The number of included cohorts, patients and controls for each LME model are reported in the tables in the results section.

Results

Participants

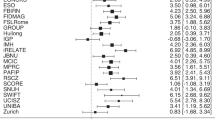

In total, we analyzed data from 4924 subjects, including 1146 people with PD (of which 88.2% had a current diagnosis versus 11.8% with a lifetime diagnosis) and 3778 HC. Demographic and clinical characteristics of each sample appear in Table 1 and a detailed breakdown is presented in Supplementary Table S1. Age distributions per scanning site appear in Supplementary Fig. S1. Briefly, the HC (mean: 34.0 ± SD 15.2 years, range: 9–72 years) and PD groups (mean: 33.8 ± SD 12.2 years; range: 10–66 years) were similar in age, but the PD group had a significantly higher proportion of females (Χ(1) = 23.6, p < 0.0001), in line with a general higher prevalence of anxiety disorders in females [24].

Cortical thickness differences associated with panic disorder

An overview of the CT findings is provided in Table 2, ordered from the strongest to the weakest effect size. Initially, nine out of 70 cortical regions showed lower thickness in individuals with PD compared to HC. However, only five of these differences remained valid after accounting for nonlinear age-by-diagnosis interactions. In the left hemisphere, lower CT was observed in the interior temporal region (d = −0.10, pFDR = 0.029), as well as the fusiform (d = −0.09, pFDR = 0.029) and pars opercularis regions (d = −0.08, pFDR = 0.049) in individuals with PD relative to HC. In the right hemisphere, CT was lower in both the precentral (d = −0.08, pFDR = 0.029) and postcentral (d = −0.08, pFDR = 0.049) regions in the PD group. An overview of the main effects of diagnosis on CT is presented in Fig. 2A.

A Lower cortical thickness (B) Smaller cortical surface area, and (C) smaller subcortical volumes in individuals with panic disorder compared to healthy controls. D Both left and right lateral ventricles were larger in individuals with an early onset of panic disorder (≤21 years) compared to those with a late disease onset (>21 years). LH Left Hemisphere, RH Right Hemisphere.

Significant diagnosis-by-age2 interactions were observed bilaterally for global CT, and unilaterally in the right middle temporal and right fusiform regions. An additional 16 regions showed significant diagnosis-by-age2 interactions without overlapping with the main effect of diagnosis, resulting in a total of 20 out of 70 CT measures exhibiting nonlinear age-related diagnostic differences (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table S2). Effect size estimates of the interactions ranged from dmin = 0.07 to dmax = 0.12, with bilateral significant interaction effects on global CT across the brain, caudal middle frontal, rostral middle frontal, isthmus cingulate, lateral orbitofrontal, superior frontal, and frontal poles. Unilateral interaction effects on CT were observed in the left precentral, and right fusiform, inferior temporal, medial orbitofrontal, middle temporal, and pars triangularis regions. No significant diagnosis-by-age or diagnosis-by-sex interactions were found for CT measures (Supplementary Tables S3, 4).

A Significant interactions between panic disorder (PD) diagnosis and age2 on 20 cortical thickness (CT) regions. Interactions were found bilaterally for the left and right caudal middle frontal, frontal poles, isthmus cingulate, lateral orbitofrontal, rostral middle frontal, and superior frontal CT. Global bilateral interaction effects on left and right mean thickness per hemisphere were also observed. Unilateral interaction effects on CT were observed in the left precentral, right fusiform, inferior temporal, medial orbitofrontal, middle temporal, and pars triangularis regions. B Post-hoc visual and statistical decomposition of diagnosis-by-age2 interaction effects on cortical thickness. Asterisks (*) denote statistical significance in brain regions where individuals with PD exhibit lower CT compared to healthy controls (HC) and all fall within the age range of 25–55 years. Brain regions in bold indicate overlap with those implicated in the main effect of diagnosis.

Post-hoc visual and statistical decomposition of the diagnosis-by-age2 interactions on cortical thickness

Visual and statistical decomposition of the quadratic interactions revealed complex patterns, wherein the magnitude and direction of effects varied based on the specific age and region examined. Visual decomposition revealed that, in general, CT appeared lower in PD than HC participants during adulthood (25–55 years), while the opposite pattern emerged during youth (<25 years) and late adulthood (>55 years)(Fig. 3B). Exploratory statistical examinations of these visual age trends were conducted by contrasting PD and HC participants across the three age groups, using the same LME models as in the main analysis. These post-hoc descriptive comparisons were not corrected for multiple testing, as they were intended for exploratory purposes. The analyses, however, revealed that only CT differences seen during adulthood demonstrated consistently negative effect sizes (dmin = −0.15 to dmax = 0.00), and were able to reach statistical significance (with ps ranging from 0.0003–0.0449). In contrast, the differences in youth and late adulthood showed both positive and negative effect sizes depending on the brain region (youth: dmin = −0.08 to dmax = 0.09; late adulthood: dmin = −0.09 to dmax = 0.19), and never reached statistical significance (youth: pmin = 0.16 to pmax = 0.94; late adulthood: pmin = 0.12 to pmax = 0.99)(Supplementary Table S5).

Surface area differences associated with panic disorder

With respect to SA, only unilateral differences were found in the left hemisphere (Table 3). Specifically, the inferior parietal (d = −0.13, pFDR = 0.021), inferior temporal (d = −0.12, pFDR = 0.022), and rostral middle frontal (d = −0.11, pFDR = 0.047) SA were smaller in people with PD relative to HC. No significant differences were found for left or right total cortical SA. No significant diagnosis-by-age, diagnosis-by-age2, or diagnosis-by-sex interactions were found for SA (Supplementary Tables S6-8). The SA findings are presented in Fig. 2B.

Subcortical brain differences associated with panic disorder

An overview of the SV findings is provided in Table 4. The bilateral volumes of the caudate (dleft = −0.12, pFDR = 0.001; dright = −0.09, pFDR = 0.020), along with the right thalamus volume (d = −0.07, pFDR = 0.038), were smaller in people with PD relative to HC. No other case-control differences were found for SV measures. No significant diagnosis-by-age, diagnosis-by-age2, or diagnosis-by-sex interactions were found for SV measures (Supplementary Tables S9-11). An overview of the subcortical findings is displayed in Fig. 2C.

Associations with anxiety symptom severity and patient subgroup analyses

No associations were found between any brain regions (CT/SA/SV) and any of the clinical anxiety severity scores, as measured per ASI, STAI_T, or BAI total (Supplementary Tables S12-20) in separate models. Exploratory analyses showed significantly larger bilateral volumes of the lateral ventricles (left: dleft = 0.31, pFDR = 0.01; dright = 0.38, pFDR = 0.002) in people with an early disease onset of PD ( ≤ 21 years; N = 145) compared to those with a late onset (>21 years; N = 309), Supplementary Table S21. No differences in CT (Supplementary Tables S22-27), SA (Supplementary Tables S28-33), or SV (Supplementary Tables S34-38) were found between medicated versus non-medicated patients, or any of the other patient subgroupings. The lateral ventricle findings are displayed in Fig. 2D.

Discussion

This worldwide effort is the largest neuroimaging study of structural brain differences in people with PD to date. Using multi-site data (28 sites worldwide) from the ENIGMA-Anxiety Working Group, comprising 1146 people with PD and 3778 HC, various cortical and subcortical differences were identified in PD across the lifespan (10–66 years). Compared to HC, individuals with PD had lower cortex throughout the brain, along with lower CT and smaller SA within specific frontal, temporal, and parietal regions. People with PD moreover showed smaller SV within the caudate and thalamus in comparison to HC. Furthermore, diagnosis-by-age2 interaction effects on CT emerged within several fronto-limbic and temporo-parietal regions, wherein CT differences between PD and HC were not consistent across different age groups. Finally, patient subgroup analyses showed that early disease onset (≤21 years) in PD was associated with larger lateral ventricles, whilst no medication, comorbidity, or severity effects were found. Together, these findings lend support to neurocircuitry models of PD, which postulate neuroanatomical changes within fronto-striato-limbic regions and additional temporo-parietal regions in its pathophysiology.

PD relates to lower cortical thickness

There was a main effect of diagnosis on CT in seven of 68 regions examined, as well as bilaterally on mean CT across the brain. However, several of these main effects were qualified by a significant diagnosis-by-age2 interaction, specifically in the right middle temporal gyrus, right fusiform gyrus, and mean CT in both the left and right hemispheres. In other words, four of the observed main effects varied as a function of nonlinear age and therefore cannot be interpreted independently of this interaction. Unilateral lower CT was seen in left fusiform, inferior temporal and pars opercularis regions, along with the right precentral, and postcentral regions. The effect sizes were fairly modest, yet comparable to prior ENIGMA work on mood disorders [14, 18, 22, 25], with Cohen’s ds ranging from −0.10–0.08. Noteworthy, a previous meta-analysis of published studies similarly points to consistently smaller CT within fronto-temporo-parietal regions in people with PD in mostly non-overlapping samples [26], further supporting the neurostructural differences reported here.

The lowest CT was found in the left inferior temporal cortex, a key part of the ventral visual pathway implicated in perception [27]. In addition, CT of the fusiform gyrus was lower in the left hemisphere; this region constitutes the basal part of the occipital and temporal lobe and is especially engaged during visual processing of faces [28], body awareness [29], and threatening bodily expressions [30]. This finding is consistent with another study identifying lower cortical thickness in the fusiform gyrus in PD, albeit unilateral to the right hemisphere [31]. The pars opercularis (inferior frontal gyrus) and pre/postcentral gyri are likewise linked to perception and emotional processing and these regions were also different in PD compared to HC in the current study. The posterior segment of the inferior frontal cortex (the pars opercularis) has also shown to be associated with negative affective bias in attention due to probable reduced executive control [32]. This region has furthermore typically been associated with the cingulo-opercular network and linked to active coping and the top-down control of emotional responses [32].

Moreover, panic attacks, key symptoms of PD, are accompanied by a range of somatic responses, such as breathing difficulties, sweating, and chest or abdominal discomfort. These symptoms suggest the involvement of brain regions associated with somatic processing. Indeed, prior work demonstrates that the postcentral gyrus (somatosensory cortex) and precentral gyrus (somatic motor cortex) play a role in emotional regulation and processing, generation of fear, and interoceptive attention [33]. For example, increased activity of the postcentral gyrus has previously been associated with generally lower symptoms of (social) anxiety [34, 35], suggesting the importance of brain regions involved in processing somatic information in anxiety symptomatology [36]. Taken together, the structural brain differences in these regions may potentially underlie the distorted processing of social, emotional, and bodily information in patients with PD [37], along with maladaptive emotion regulation and somatosensory arousal. More research, however, is needed to fully grasp the role these cortical regions play in PD, and how they may interact within and across other brain networks.

PD relates to smaller cortical surface area

People with PD exhibited smaller SA relative to HC in three out of 68 regions. However, no group differences emerged for total SA measures, in either the left or right hemisphere, suggesting a regional but not global association between PD and SA. This study is the first to report significant SA differences in PD using a whole-brain analysis. Left-lateralized smaller SA was observed in the inferior parietal, inferior temporal gyrus (also observed in CT), and rostral middle frontal regions. Effect sizes were slightly larger compared to case-control differences in CT, but still relatively small and on par with prior ENIGMA work on internalizing psychopathology [14], with Cohen’s ds ranging from −0.11–0.13. Both the location and direction of effects importantly mirror a recent small-scale VBM-based meta-analysis, which similarly showed consistently smaller cortical volume within fronto-temporo-parietal regions among people with PD [26].

The inferior parietal lobe, a key part of the posterior Default Mode Network, is involved in memory and perceptual processing [38], and perceptual processes are typically perturbed in people with PD. The inferior parietal lobe might therefore serve as a plausible substrate/key region for these aberrant processes. The inferior temporal gyrus finding interestingly converges across SA and CT case-control comparisons, providing further evidence for the role of this area in sensory-related dysfunction and negatively biased interoceptive sensory processing [39]. Finally, previous structural studies have reported overall size reductions within the rostral middle frontal cortex among people with PD [26], including associations with higher Panic Disorder Severity Scale and lower Global Assessment of Functioning scores [40]. Functional MRI studies also show dysfunction of the rostral middle frontal cortex in PD, including hypoactivity detected by a near-infrared spectroscopy study [41], decreased [18 F]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake [42], and induced panic attacks by activating the middle frontal cortex with cholecystokinin tetrapeptide in HC [43]. The smaller SA in the rostral middle frontal cortex reported here in PD compared to HC further supports the involvement of this brain region in PD pathophysiology.

Further research is needed to explore if the SA of these brain regions could, for example, inform prediction of treatment efficacy. In contrast to the CT findings, no interactions between diagnostic status and age or age2 were found for any of the SA measures. This may potentially suggest that, in contrast to above mentioned CT changes, SA differences in PD are more stable across the lifespan. Indeed, the current cross-sectional study did not reveal SA differences between patient subgroups that differed on key clinical characteristics such as age of onset or medication use. However, it remains to be elucidated whether disease duration, psychotropic medication, or other factors may influence SA changes over time, and longitudinal studies may shed light on such processes.

PD relates to smaller subcortical volumes

People with PD exhibited smaller SV relative to HC in three out of 16 regions. This included smaller caudate nuclei bilaterally and a smaller right thalamus unilaterally, with small effect sizes (Cohen’s ds = −0.12–0.07) on par with previous ENIGMA work on internalizing psychopathology [14]. Critically, smaller thalamic and striatal volumes also emerged in a recent small-scale meta-analysis of previously published data on PD [26], further highlighting putative involvement of these subcortical regions in PD pathophysiology.

The caudate nuclei, which are key components of the corticostriatal circuitry subserving reward-related, habitual and goal-directed behaviors [44,45,46], have been implicated in clinical anxiety and PD specifically. Previous small-scale meta-analytic work has accordingly pointed to smaller caudate volumetrics in PD [47]. The implication of the thalamus here is consistent with its hub-like functionality within networks conferring defensive reactivity [48], with anomalies in its function, volume, and shape being reported in people with PD [26, 49]. However, other paralimbic subcomponents of these networks (e.g., hippocampus, amygdala, insula) were not significantly related to PD in the current structural mega-analysis, and the subcortical findings generally did not overlap with those found in ENIGMA Anxiety-initiated mega-analyses of other anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized (GAD) and social anxiety disorders (SAD) [50, 51]).

In short, the GAD mega-analysis found no main effect of GAD on brain structure, and only documented diagnosis-by-sex interactions within the diencephalon (larger diencephalon in male GAD vs. male HC, no differences in females). The SAD mega-analysis revealed smaller putamen volumes in SAD vs. HC, along with diagnosis-by-age effects on the putamen (smaller putamen in adult SAD vs. HC, no differences in youth). None of the studies reported case-control differences in cortical morphology. Future vertex-wise work is needed to examine whether these volumetric differences are accompanied by shape abnormalities, while multimodal neuroimaging is warranted to assess whether these structural differences are accompanied by functional and connectional shifts in PD. In sum, the current mega-analysis points to robust and specific changes in thalamo-striatal volumetrics in PD, which might putatively underpin maladaptive behavior and excessive fear.

Diagnosis-by-age2 interactions on cortical thickness

While we did not observe any diagnosis-by-age interactions on any of the brain regions, significant diagnosis-by-age2 interactions were found for 20 of the 70 CT measures, encompassing fronto-limbic and temporo-parietal regions that shape how social, emotional, and visceral information is perceived, processed, and regulated. Of these 20 regions, four also emerged in the main PD vs. HC comparison (main effect of diagnosis), which renders diagnostic effects on these four regions conditional to nonlinear age effects. Further scrutiny of these nonlinear interactions suggested complex age effects, wherein CT differences between PD and HC were not consistent across different age groups. In general, CT appeared lower in PD compared to HC participants during adulthood (25–55 years), while the opposite pattern emerged during youth (<25 years) and late adulthood (>55 years). Post-hoc analyses, however, revealed that only the CT differences seen during adulthood demonstrated consistently negative effect sizes (dmin = −0.15 to dmax = 0.00), and were able to reach statistical significance (with ps ranging from 0.0003–0.0449). In contrast, the differences in youth and late adulthood showed both positive and negative effect sizes depending on the brain region (youth: dmin = −0.08 to dmax = 0.09; late adulthood: dmin = −0.09 to dmax = 0.19), but never reached statistical significance (youth: pmin = 0.16 to pmax = 0.94; late adulthood: pmin = 0.12 to pmax = 0.99)(Supplementary Table S5). While these findings may suggest abnormal nonlinear effects of development and aging on CT in PD pathophysiology, it is important to note that current observations were derived from cross-sectional analyses. Moreover, the youth and late adulthood age groups contained significantly fewer participants (Supplementary Fig. S2), rendering the group comparisons in these populations statistically less robust, warranting a more cautious interpretation of these findings. Longitudinal examinations with a more balanced distribution of age could tackle these issues more definitively.

The specific trajectory of CT development is still debated, with evidence of constant, linear, quadratic, and even cubic patterns of CT development being reported, depending on the specific age range and region examined [52, 53]. These mixed findings are putatively linked to interactions between the development of CT and sulcal/gyral topology, wherein thicker sulcal cortex displays linear thinning over time, while lower gyral cortex displays nonlinear thinning patterns. Our results potentially suggest that abnormal maturational shifts in cellular or molecular processes that shape radial cortical expansion -and thus CT- are involved in PD, rather than tangential expansion mechanisms that determine surface area [54]. Cortical thickness and surface area are in fact under distinct genetic control, follow specific developmental trajectories, and are differentially associated with cognitive function and psychopathology [55,56,57]. While we lack the longitudinal data to test above mentioned possibilities, at the very least, we may conclude that PD probably involves some fronto-limbic and temporo-parietal CT changes that are not stable across the lifespan. This fits with the emerging conceptualization of mental disorders as involving abnormal brain maturational processes, with evidence of genetic overlap between cortical maturation and psychopathology [58, 59]. Similar to SA, and in contrast to our CT findings, no interactions were found between diagnostic status and age or age2 for any of the SV measures, suggesting that SV differences in PD may be less dynamic across the lifespan.

PD early disease onset associated with larger lateral ventricles

To examine whether basic clinical characteristics such as the severity of anxiety symptoms, comorbidity (i.e., depression or other anxiety disorders), and medication use (any psychotropic medication or SSRIs/SNRIs specifically) potentially exacerbated the link between PD and structural brain differences, we performed stratified analyses within patient subgroups. First, we found no significant differences between individuals with a current diagnosis of PD and those with a lifetime diagnosis. However, it is important to note that individuals with a lifetime diagnosis comprised only a small portion of the PD group (11.8%). Given that most literature on the neuroanatomical differences in PD focuses on individuals with a current diagnosis, future research with larger samples are needed to determine whether lifetime PD is associated with lasting structural brain changes that persist even after acute symptoms have subsided. Second, our analyses demonstrated larger lateral ventricles in both brain hemispheres in people with an early disease onset of PD (≤21 years) compared to those with a late disease onset (>21 years). This finding potentially suggests that larger ventricles may be a consequence of a longer disease duration. To further explore this finding, we conducted two additional post-hoc analyses: a) comparing the early and late onset patient groups to healthy controls, and b) examining the interaction between age² and onset status (early vs. late) in relation to lateral ventricle volumes. However, both analyses yielded non-significant results, indicating that the findings were independent of nonlinear age effects, and mainly differentiated early vs. late onset PD patients. Future studies with a longitudinal design should be carried out to investigate whether larger lateral ventricles are a consequence of PD, represent a vulnerability to the disorder, or that both are influenced by “third” factors.

While ventricle expansions are commonly observed in mental disorders, specifically in schizophrenia [60, 61], its pathophysiology remains elusive. It has previously been suggested that thalamic shrinkage could be an important contributor to ventricular enlargement [62], and indeed a smaller thalamus volume was observed in people with PD in the current study, albeit not specifically in those with an early disease onset. At the same time, some studies suggest that ventricular changes are driven by cortical thinning [63], and although overall cortical thinning was observed amongst persons with PD, this was not limited to those with an early disease onset. Future work is clearly needed to reveal the underlying mechanisms for lateral ventricle expansion in people with an early PD disease onset. Enlargement of the brain’s fluid-filled lateral ventricles is also a defining feature of an aging brain [64], and it would be interesting to see whether people with an early onset of PD show significantly older appearing brains than expected for their chronological age, as has previously been demonstrated in other mental disorders [65, 66]. Finally, the current large-scale analysis failed to show significant associations between brain morphology and severity of anxiety-related symptoms or psychotropic medication use, consistent with prior neurostructural studies on PD (albeit gray matter volume analyses)[10, 67,68,69,70]. More work is thus needed to better understand how key clinical characteristics may impact or shape structural brain differences in PD.

Strengths and limitations

Small-scale studies have been shown to produce findings that are difficult to replicate [14, 71, 72]. Major strengths of this study therefore include the large, heterogeneous, multi-site sample (N = 4924, 28 global sites), harmonized preprocessing, and statistical rigor of the analyses (i.e., all main findings reported here were FDR-corrected). The cortical and subcortical differences presented here for PD therefore represent the most robust neuroanatomical signature of this disorder to date, even though the effect sizes were small but in line with neuroimaging effect sizes found in other affective disorders such as MDD [73]. However, due to the substantial sample size, we were able to make comparisons between specific patient subgroups, leading to the identification of significant lateral ventricle differences with larger effect sizes (Cohen’s ds: 0.31–0.38) for patients with an early disease onset compared to those with a late onset of PD. To examine whether this finding is a direct consequence of PD or can be clinically useful, further investigation into the longitudinal changes of these subcortical structures is required.

Despite the large pooled mega-analyses, we have to acknowledge that the sample size per contributing site still remained rather limited, although random intercepts for site were fitted to account for site heterogeneity. Additionally, there was relatively low availability of the panic disorder symptom severity (PDSS) questionnaire (N = 196 contributed by only N = 4 sites, of which only three had cortical parcellations available). Nevertheless, individuals with PD often strongly endorse high scores on other symptom severity scales, such as the considered BAI, STAI-T, and ASI, underscoring their relevance in this population. A pairwise correlation plot of the symptom severity scales included in the current study can be found in Supplementary Fig. S3. To establish a complete and reliable picture of the neuroanatomical differences consistently associated with PD and its symptom severity, future studies with increasing subject numbers are needed to replicate and extend the current findings. In addition, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes causal conclusions, but also limits a more thorough scrutiny of the nonlinear diagnosis-by-age2 interactions on cortical thickness that emerged. Longitudinal studies are needed to further examine the effects of clinical, sociodemographic and biological factors on structural brain differences in PD. Despite previous ENIGMA studies of structural brain differences in MDD showing slightly larger effect sizes than observed here [22, 23], the current study did not further observe significant differences between PD individuals with and without comorbid depression. Therefore, a transdiagnostic approach towards brain structural differences in mental disorders in general, and anxiety disorders in particular, is warranted to pinpoint shared and unique neuroanatomical signatures.

Conclusions

In conclusion, by pooling neuroimaging data and harmonizing data processing and analysis across 28 international studies, our examination of 4924 individuals revealed subtle but robust structural brain differences in PD. The analysis specifically implicates smaller cortical size within fronto-limbic and temporo-parietal regions, along with smaller volumes of thalamic and caudate regions in PD pathophysiology. Diagnosis-by-Age2 interactions and early PD onset moreover impacted cortical thickness and ventricle size, respectively, pointing to putative developmental and aging processes at play in PD. The findings may provide a tentative neuroanatomical account for altered processing of social, emotional, and bodily information, along with maladaptive emotion regulation and somatosensory arousal in PD. Further multimodal and longitudinal brain imaging research using large-scale databases is needed to delineate how (micro)structural, functional, and connectional alterations may interactively relate to PD illness progression, persistence, and remission. Given its unprecedented scale, the current study reflects an important milestone towards identifying the structural brain correlates of PD.

Data availability

The ENIGMA-Panic Disorder Working Group is open to sharing the data and code from this investigation with researchers for secondary data analysis. To request access to structural brain, clinical, and demographic data, an analysis plan can be submitted to the ENIGMA-Anxiety Working Group. Data access is dependent on approval by PI’s from contributing cohorts to the consortium. Requests or questions regarding data availability or sharing should be sent to M. Aghajani (m.aghajani@fsw.leidenuniv.nl).

Code availability

Code for analysis is available at: https://github.com/WillemB2104/ENIGMA-PD.

References

Goddard AW. The neurobiology of panic: a chronic stress disorder. Chronic Stress. 2017;1:2470547017736038.

de Jonge P, Roest AM, Lim CCW, Florescu SE, Bromet EJ, Stein DJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of panic disorder and panic attacks in the world mental health surveys. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:1155–77.

Lewis G. DSM-IV. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. By the American Psychiatric Association. (Pp. 886; £34.95.) APA: Washington, DC.1994. Psychol Med. 1996;26:651–2.

Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB. Panic disorder. Lancet. 2006;368:1023–32.

Freire RC, Perna G, Nardi AE. Panic disorder respiratory subtype: psychopathology, laboratory challenge tests, and response to treatment. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2010;18:220–9.

Shackman AJ, Fox AS. Two decades of anxiety neuroimaging research: new insights and a look to the future. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:106–9.

Bas-Hoogendam JM, Groenewold NA, Aghajani M, Freitag GF, Harrewijn A, Hilbert K, et al. ENIGMA-anxiety working group: rationale for and organization of large-scale neuroimaging studies of anxiety disorders. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43:83–112.

Del Casale A, Serata D, Rapinesi C, Kotzalidis GD, Angeletti G, Tatarelli R, et al. Structural neuroimaging in patients with panic disorder: findings and limitations of recent studies. Psychiatr Danub. 2013;25:108–14.

Lai C-H, Wu Y-T. The gray matter alterations in major depressive disorder and panic disorder: Putative differences in the pathogenesis. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:1–6.

Asami T, Yamasue H, Hayano F, Nakamura M, Uehara K, Otsuka T, et al. Sexually dimorphic gray matter volume reduction in patients with panic disorder. Psychiatry Res: Neuroimaging. 2009;173:128–34.

Kunas SL, Hilbert K, Yang Y, Richter J, Hamm A, Wittmann A, et al. The modulating impact of cigarette smoking on brain structure in panic disorder: a voxel-based morphometry study. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2020;15:849–59.

Wu Y, Zhong Y, Ma Z, Lu X, Zhang N, Fox PT, et al. Gray matter changes in panic disorder: a voxel-based meta-analysis and meta-analytic connectivity modeling. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2018;282:82–89.

Kong X-Z, ENIGMA Laterality Working Group, Francks C. Reproducibility in the absence of selective reporting: An illustration from large-scale brain asymmetry research. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43:244–54.

Thompson PM, Jahanshad N, Ching CRK, Salminen LE, Thomopoulos SI, Bright J, et al. ENIGMA and global neuroscience: A decade of large-scale studies of the brain in health and disease across more than 40 countries. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:100.

Zugman A, Harrewijn A, Cardinale EM, Zwiebel H, Freitag GF, Werwath KE, et al. Mega-analysis methods in ENIGMA: The experience of the generalized anxiety disorder working group. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43:255–77.

Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, Albert M, Dieterich M, Haselgrove C, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. 2002;33:341–55.

Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–80.

Boedhoe PSW, Schmaal L, Abe Y, Alonso P, Ameis SH, Anticevic A, et al. Cortical abnormalities associated with pediatric and adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: findings from the enigma obsessive-compulsive disorder working group. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:453–62.

Boedhoe PSW, Schmaal L, Abe Y, Ameis SH, Arnold PD, Batistuzzo MC, et al. Distinct subcortical volume alterations in pediatric and adult OCD: A worldwide meta- and mega-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:60–70.

Barnes J, Ridgway GR, Bartlett J, Henley SMD, Lehmann M, Hobbs N, et al. Head size, age and gender adjustment in MRI studies: a necessary nuisance? Neuroimage. 2010;53:1244–55.

Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2007;82:591–605.

Schmaal L, Hibar DP, Sämann PG, Hall GB, Baune BT, Jahanshad N, et al. Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;22:900–9.

Schmaal L, Veltman DJ, van Erp TGM, Sämann PG, Frodl T, Jahanshad N, et al. Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;21:1–7.

McLean CP, Anderson ER. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:496–505.

Hibar DP, Westlye LT, Doan NT, Jahanshad N, Cheung JW, Ching CRK, et al. Cortical abnormalities in bipolar disorder: an MRI analysis of 6503 individuals from the ENIGMA bipolar disorder working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:932–42.

Wang X, Cheng B, Wang S, Lu F, Luo Y, Long X, et al. Distinct grey matter volume alterations in adult patients with panic disorder and social anxiety disorder: A systematic review and voxel-based morphometry meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:805–23.

Conway BR. The organization and operation of inferior temporal cortex. Annu Rev Vis Sci. 2018;4:381–402.

Kanwisher N, Yovel G. The fusiform face area: a cortical region specialized for the perception of faces. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361:2109–28.

Peelen MV, Downing PE. Selectivity for the human body in the fusiform gyrus. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:603–8.

Kret ME, Pichon S, Grèzes J, de Gelder B. Similarities and differences in perceiving threat from dynamic faces and bodies. an fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2011;54:1755–62.

Ni M-F, Wang X-M, Wang H-Y, Chang Y, Huang X-F, Zhang B-W. Regional cortical thinning and cerebral hypoperfusion in patients with panic disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:138–45.

Hu Y, Dolcos S. Trait anxiety mediates the link between inferior frontal cortex volume and negative affective bias in healthy adults. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2017;12:775–82.

Kropf E, Syan SK, Minuzzi L, Frey BN. From anatomy to function: the role of the somatosensory cortex in emotional regulation. Braz J Psychiatry. 2019;41:261–9.

Kilts CD, Kelsey JE, Knight B, Ely TD, Bowman FD, Gross RE, et al. The neural correlates of social anxiety disorder and response to pharmacotherapy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2243–53.

Li Y, Meng Y, Yuan M, Zhang Y, Ren Z, Zhang Y, et al. Therapy for adult social anxiety disorder: a meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:e1429–e1438.

Li X, Zhang M, Li K, Zou F, Wang Y, Wu X, et al. The altered somatic brain network in state anxiety. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:465.

Oliva A, Torre S, Taranto P, Delvecchio G, Brambilla P. Neural correlates of emotional processing in panic disorder: A mini review of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:906–14.

Raichle ME. The brain’s default mode network. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:433–47.

Uchida RR, Del-Ben CM, Busatto GF, Duran FLS, Guimarães FS, Crippa JAS, et al. Regional gray matter abnormalities in panic disorder: a voxel-based morphometry study. Psychiatry Res. 2008;163:21–29.

Asami T, Takaishi M, Nakamura R, Yoshida H, Yoshimi A, Whitford TJ, et al. Cortical thickness reductions in the middle frontal cortex in patients with panic disorder. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:199–202.

Deppermann S, Vennewald N, Diemer J, Sickinger S, Haeussinger FB, Notzon S, et al. Does rTMS alter neurocognitive functioning in patients with panic disorder/agoraphobia? An fNIRS-based investigation of prefrontal activation during a cognitive task and its modulation via sham-controlled rTMS. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:542526.

Kang E-H, Park J-E, Lee K-H, Cho Y-S, Kim J-J, Yu B-H. Regional brain metabolism and treatment response in panic disorder patients: an [18F]FDG-PET study. Neuropsychobiology. 2012;66:106–11.

Eser D, Leicht G, Lutz J, Wenninger S, Kirsch V, Schüle C, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of CCK-4-induced panic attacks in healthy volunteers. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:511–22.

Haber SN Anatomy and connectivity of the reward circuit. In: Dreher J-C, Tremblay L, editors. Decision Neuroscience, San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 3–19.

Sequeira SL, Silk JS, Ladouceur CD, Hanson JL, Ryan ND, Morgan JK, et al. Association of neural reward circuitry function with response to psychotherapy in youths with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:343–51.

Baik J-H. Stress and the dopaminergic reward system. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52:1879–90.

Lai C-H. Gray matter deficits in panic disorder: a pilot study of meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31:287–93.

Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:493–505.

Feldker K, Heitmann CY, Neumeister P, Bruchmann M, Vibrans L, Zwitserlood P, et al. Brain responses to disorder-related visual threat in panic disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37:4439–53.

Harrewijn A, Cardinale EM, Groenewold NA, Bas-Hoogendam JM, Aghajani M, Hilbert K, et al. Cortical and subcortical brain structure in generalized anxiety disorder: findings from 28 research sites in the ENIGMA-Anxiety Working Group. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:502.

Groenewold NA, Bas-Hoogendam JM, Amod AR, Laansma MA, Van Velzen LS, Aghajani M, et al. Volume of subcortical brain regions in social anxiety disorder: mega-analytic results from 37 samples in the ENIGMA-anxiety working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:1079–89. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01933-9.

Sowell ER, Peterson BS, Kan E, Woods RP, Yoshii J, Bansal R, et al. Sex differences in cortical thickness mapped in 176 healthy individuals between 7 and 87 years of age. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1550–60.

Kaczkurkin AN, Raznahan A, Satterthwaite TD. Sex differences in the developing brain: insights from multimodal neuroimaging. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:71–85.

Rakic P. Specification of cerebral cortical areas. Science. 1988;241:170–6.

Winkler AM, Greve DN, Bjuland KJ, Nichols TE, Sabuncu MR, Håberg AK, et al. Joint analysis of cortical area and thickness as a replacement for the analysis of the volume of the cerebral cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:738–49.

Gerrits NJHM, van Loenhoud AC, van den Berg SF, Berendse HW, Foncke EMJ, Klein M, et al. Cortical thickness, surface area and subcortical volume differentially contribute to cognitive heterogeneity in parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148852.

Schnack HG, van Haren NEM, Brouwer RM, Evans A, Durston S, Boomsma DI, et al. Changes in thickness and surface area of the human cortex and their relationship with intelligence. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:1608–17.

Patel Y, Parker N, Shin J, Howard D, French L, Thomopoulos SI, et al. Virtual histology of cortical thickness and shared neurobiology in 6 psychiatric disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:47–63.

Parker N, Patel Y, Jackowski AP, Pan PM, Salum GA, Pausova Z, et al. Assessment of neurobiological mechanisms of cortical thinning during childhood and adolescence and their implications for psychiatric disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:1127–36.

Kempton MJ, Stahl D, Williams SCR, DeLisi LE. Progressive lateral ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of longitudinal MRI studies. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:54–62.

Van Erp TGM, Hibar DP, Rasmussen JM, Glahn DC, Pearlson GD, Andreassen OA, et al. Subcortical brain volume abnormalities in 2028 individuals with schizophrenia and 2540 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:547–53.

Gaser C, Nenadic I, Buchsbaum BR, Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS. Ventricular enlargement in schizophrenia related to volume reduction of the thalamus, striatum, and superior temporal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:154–6.

Svancer P, Spaniel F. Brain ventricular volume changes in schizophrenia. a narrative review. Neurosci Lett. 2021;759:136065.

Shook BA, Lennington JB, Acabchuk RL, Halling M, Sun Y, Peters J, et al. Ventriculomegaly associated with ependymal gliosis and declines in barrier integrity in the aging human and mouse brain. Aging Cell. 2014;13:340–50.

Han LKM, Dinga R, Hahn T, Ching CRK, Eyler LT, Aftanas L, et al. Brain aging in major depressive disorder: results from the ENIGMA major depressive disorder working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:5124–39.

Constantinides C, Han LKM, Alloza C, Antonucci L, et al. Brain ageing in schizophrenia: evidence from 26 international cohorts via the ENIGMA schizophrenia consortium. Mol Psychiatry, 2023;28:1201–9.

Asami T, Hayano F, Nakamura M, Yamasue H, Uehara K, Otsuka T, et al. Anterior cingulate cortex volume reduction in patients with panic disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:322–30.

Asami T, Nakamura R, Takaishi M, Yoshida H, Yoshimi A, Whitford TJ, et al. Smaller volumes in the lateral and basal nuclei of the amygdala in patients with panic disorder. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207163.

Massana G, Serra-Grabulosa JM, Salgado-Pineda P, Gastó C, Junqué C, Massana J, et al. Amygdalar atrophy in panic disorder patients detected by volumetric magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage. 2003;19:80–90.

Na K-S, Ham B-J, Lee M-S, Kim L, Kim Y-K, Lee H-J, et al. Decreased gray matter volume of the medial orbitofrontal cortex in panic disorder with agoraphobia: a preliminary study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:195–200.

Marek S, Tervo-Clemmens B, Calabro FJ, Montez DF, Kay BP, Hatoum AS, et al. Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals. Nature. 2022;603:654–60.

Miller KL, Alfaro-Almagro F, Bangerter NK, Thomas DL, Yacoub E, Xu J, et al. Multimodal population brain imaging in the UK Biobank prospective epidemiological study. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1523–36.

Winter NR, Leenings R, Ernsting J, Sarink K, Fisch L, Emden D, et al. Quantifying deviations of brain structure and function in major depressive disorder across neuroimaging modalities. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:879–88.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all research participants, ENIGMA-Panic Disorder working group contributors and collaborators for sharing their data and promoting team science. MA has received funding from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development—ZonMw (research fellowship number 06360322210035), Dutch Research Council NWO (SSH Open Competition number 15810), Leiden University Fund (project Youth Mental Health Meets Big Data Analytics, grant number LUF23075-5-306), Leiden University Fund (project grant number W213085-5), Amsterdam Neuroscience (Amsterdam Neuroscience Alliance Grant Project.). JBH received research grants from the Dutch Research Council (NWO; 019.201SG.022), Medical Delta (Talent Acceleration Call) and the Dutch Research Agenda (NWA-NeurolabNL NWA.1418.22.025). JB was supported by Innovative Medizinische Forschung (IMF; BÖ112202). FB was supported by Medical faculty “Innovative Medizinische Forschung” (ME 121805). PB was partially supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Education and Research - MUR (‘Dipartimenti di Eccellenza’ Programme 2023–27 - Dept. of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, Università degli Studi di Milano), the Italian Ministry of Health (Hub Life Science- Diagnostica Avanzata, HLS-DA, PNC-E3-2022-23683266– CUP: C43C22001630001 / MI-0117; Ricerca Corrente 2025; RF-2019-12371349), the Fondazione Cariplo (Made In Family, grant number 2019–3416), and the ERANET Neuron JTC 2023 (ERP-2023-23684211 - ERP-2023-Neuron-ResilNet). EM was supported by the European Union – NextGeneration EU (PRIN 2022 PNRR, grant n. P20229MFRC) and by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN 2022, grant n. 2022RXM3H7). UD was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG, grant FOR2107 DA1151/5-1 and DA1151/5-2 to UD; SFB-TRR58, Projects C09 and Z02 to UD) and the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF) of the medical faculty of Münster (grant Dan3/012/17 to UD); German multicenter consortium “Neurobiology of Affective Disorders. A translational perspective on brain structure and function“, funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG; Forschungsgruppe/ Research Unit FOR2107) Work Package WP1, FOR2107/MACS cohort and brainimaging: co-speaker FOR2107; DA 1151/5-1, DA 1151/5-2. GF was supported by NIH K23MH114023. NG work was made possible in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author. LH was funded by the Rubicon award (grant number 452020227) and Veni award (grant number 09150162210201) from the Dutch Research Council (NWO). OvdH was supported by AGIKO-grant MW 940–37–018 from the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, NWO). NJ was supported by R01MH117601. TK was supported by BMBF Panic Net, BMBF Protect-AD. EL was supported by the Medical faculty “Innovative Medizinische Forschung” (LE 121904). UL was supported by Research Unit 5187 (DFG FOR 5187) from the German Research Foundation. BM was supported by NIMH. JN was supported by NIH grant R01MH101486. DP was supported by NIMH-IRP Project ZIA-MH002781. AR was funded by a fellowship from the German Research Foundation when data was collected and funded by a fellowship from MQ: Transforming Mental health when data was re-analysed for this project. IR was supported by BMBF - German Federal Ministry of Education and Research; for PROTECT-AD. BS acknowledges that parts of the data come from the German multicenter trial ‘Mechanisms of Action in CBT (MAC),’ which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; Project no. 01GV0615 and 01GV0611 [PANIC-Net], 01EE1402E [PROTECT-AD]) as part of the BMBF Psychotherapy Research Funding Initiative. It is further supported by the German Research Foundation (BS: STR 1146/18-1; TK: KI 588/22-1; UD: DA 1151/11‑1 as part of the FOR2107). BSJ was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health K01MH118428 and R01MH131532, National Eye Institute Core Grant #P30 EY001319, and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation NARSAD Young Investigator. DS was supported by SAMRC. ES was supported by Medical faculty “Innovative Medizinische Forschung” (LE 121904). TS was supported by SFB-TRR 58. AT was supported by the Brain and Behavioral Research Foundation NARSAD Grant. PT was supported by the core funding for ENIGMA, provided by the NIH Big Data to Knowledge (BD2K) program under consortium grant U54 EB020403. ST is supported in part by NIH grants R01MH123163, R01MH121246, and R01MH116147. AW was supported by NIMH-IRP Project ZIA-MH002781. AZ was supported by NIMH-IRP Project ZIA-MH002781. The MPIP Munich Morphometry Sample comprises images acquired as part of the Munich Antidepressant Response Signature Study and the Recurrent Unipolar Depression (RUD) Case-Control study performed at the MPIP. We wish to acknowledge Anna Olynyik and radiographers Rosa Schirmer, Elke Schreiter, Reinhold Borschke and Ines Eidner for image acquisition and data preparation. We thank Dorothee P. Auer for local study management in the initial phase of the RUD study. The study is supported by a grant of the Exzellenz-Stiftung of the Max Planck Society. This work has also been funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the framework of the National Genome Research Network (NGFN), FKZ 01GS0481. The SHIP study has received funding from the following institutions: Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the Ministry of Cultural Affairs as well as the Social Ministry of the Federal State of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. SHIP is also part of the Community Medicine Research Network of the University Medicine Greifswald. Magnetic resonance imaging examinations were supported by Siemens Healthineers, Siemens Healthcare GmbH (Erlangen, Germany). This research was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contributions of the NIH author(s) were made as part of their official duties as NIH federal employees, are in compliance with agency policy requirements, and are considered Works of the United States Government. However, the findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. TA: Data curation. JB: Writing - Review & Editing. JBH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Project Administration. RB: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. JB: Resources, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. PB: Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing.FB: Writing - Review & Editing. WB: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. RB: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. NC: Data curation. UD: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. KDohm: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. KDomschke: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. TD: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. AE: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. GF: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. AF: Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. HB: Conceptualization, Resources, Project administration. NG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. DG: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. LH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. KH: Formal analysis, Writing - Review & Editing. DH: Conceptualization, Project administration. NJ: Resources, Project administration. TK: Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. ML: Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing. SL: Methodology, Validation, Data curation. EL: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. UL: Writing - Review & Editing. EM: Methodology, Data curation. SM: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. HM: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. BMilrod: Investigation, Project administration, Funding acquisition. BMwangi: Software, Investigation, Resources, Data curation. JN: Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. PO: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. BP: Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. DP: Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. SP: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. AR: Investigation, Project administration. IR: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. PS: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. TS: Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. LS: Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. ES: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. JS: Conceptualization, Methodology, software, Investigation, Resources, Data curation. DS: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. BS: Resources, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. TS: Methodology, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. BSJ: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. AT: Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing. ST: Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. PT: Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition, Project administration. OvdH: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. NvdW: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Project administration. DV: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing. KW: Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. MW: Software, Investigation, Resources, Data curation. YY: Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing - Review & Editing. GZ: Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

GF owns equity in Alto Neuroscience and has received monetary compensation for consulting work for SynapseBio AI. HG has received speaker’s honoraria from Neuraxpharma, Servier, Fresenius, Janssen-Cilag. JS provides interest or action in ALKERMES – Research Grant; ALLERGAN – Research Grant; ASOFARMA – Consultant; ATAI – Stock – less than U.S. $5k; BOEHRINGER Ingelheim – Consultant; COMPASS – Research Grant; JOHNSON & JOHNSON – Consultant; LIVANOVA - Consultant; PFIZER - Consultant; PULVINAR NEURO LLC – Consultant; RELMADA - Consultant; SANOFI - Consultant; SUNOVIAN - Consultant” unrelated to the current manuscript. KH is a scientific advisor and received virtual stock options of Mental Tech GmbH, which develops an AI-based chatbot providing mental health support. DJS reports consultancy honoraria from Discovery Vitality, Kanna, L’Oreal, Lundbeck, Orion, Servier, Seaport Therapeutics, Takeda, and Wellcome. All other authors do not report any competing interests.

Ethics approval

All participating research sites obtained approval from local ethics committees. All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed consent

We confirm that all human subjects provided informed consent in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, L.K.M., Bruin, W.B., Bas-Hoogendam, J.M. et al. Structural brain differences associated with panic disorder: an ENIGMA-Anxiety Working Group mega-analysis of 4924 individuals worldwide. Mol Psychiatry (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03376-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03376-4