Abstract

Objectives

Lifestyle intervention, especially dietary modification, has been the cornerstone in preventing type 2 diabetes (T2D). We aimed to investigate the associations of various protein intake exposures with the risk of incident T2D in adults with or without metabolic diseases.

Methods

We followed 29517 residents enrolled in the Shanghai Suburban Adult Cohort and Biobank (SSACB) without diabetes at baseline through the electronic information system. Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the associations of various protein intake exposures with the risk of incident T2D, visualized by restricted cubic splines (RCS). Propensity-score matching and subgroup analysis were used to characterize the association between total protein and incident T2D by metabolic diseases. Meta-analysis further explored the association between protein intake and incident T2D in broader populations.

Results

In SSACB, 1511 (5.1%) participants developed T2D during a median follow-up period of 5.69 years. A U-shaped association between total protein and risk of incident T2D was found (protective range: 12.20-16.85 percentage energy (%E), cut-off point: 14.53%E). The U-shaped association (P-nonlinear < 0.001) remained in adults with hypertension with a narrower protective range (12.20–15.35%E), with a linear association in adults with NAFLD (HR per 1%E: 0.952, 95% CI: [0.910, 0.995]), whereas no significant association in adults with hyperlipidemia or central obesity. A negative association between plant protein and risk of incident T2D was also found in SSACB (HR per 1%E: 0.947, 95% CI: [0.900, 0.996]). In addition, the U-shaped association of total protein with the risk of incident T2D was reaffirmed in the dose-response meta-analysis (cut-off point: 15.10%E).

Conclusion

In SSACB, a U-shaped association between total protein intake and risk of incident T2D was found, which was reaffirmed in the dose-response meta-analysis, and differed by metabolic diseases, especially hypertension and NAFLD. Moreover, plant protein was inversely associated with the risk of incident T2D.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes is a major global health problem, and an estimated 537 million (~10.5%) adults (20–79 years) have been living with diabetes since 2021, with a predicted rise to 783 million by 2045 [1]. Since China has the largest population with diabetes in the world, and almost half of them are undiagnosed [1], the primary prevention of diabetes has become imperative. Lifestyle intervention, especially dietary modification, has been the cornerstone in preventing type 2 diabetes (T2D) [2]. However, dietary recommendations on protein intake proposed by guidelines or consensus statements for diabetes mainly focus on adults who are already diagnosed with diabetes or pre-diabetes and are inconclusive [3,4,5,6]. Moreover, a non-linear association of protein intake with the risk of incident T2D has been found in the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS) [7], which is not in agreement with the results of previous cohort studies in Western countries [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], indicating the impact of the specificity of dietary patterns in China.

More importantly, studies have shown that adults with metabolic diseases (such as hypertension [16], non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [17], hyperlipidemia [18], and obesity [19, 20]) have a higher risk of developing T2D. Recent studies have suggested that high-protein diets might improve insulin resistance by altering the levels of metabolic signatures, such as leptin, sex hormone binding globulin, and inflammation factors [21], as well as by enhancing gut barrier function and gut microbiome [22]. Still, most randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted in populations with T2D or obesity [23, 24], and limited studies focused on the impacts of protein intake on T2D among populations with other metabolic diseases, such as hypertension [23] and hyperlipidemia [25], and few studies have distinguished the health status of adults when exploring the association of protein intake with T2D.

To address the knowledge gap for dietary protein recommendations to prevent T2D, our study aims to (1) investigate the associations of various protein intake exposures with the risk of incident T2D in the participants of Shanghai Suburban Adult Cohort and Biobank (SSACB) and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies to reveal optimal daily protein intake and recommend food sources of protein and (2) explore the associations between protein intake and risk of incident T2D in the participants of SSACB with differed metabolic diseases to specify the protein recommendations for such populations.

Subjects and methods

Study design and population

Details of the SSACB cohort design were described elsewhere [26]. In brief, 36605 residents between 20 and 74 years old in the Songjiang district were recruited between 2016 and 2017. We first excluded the participants with extreme dietary energy (male: >4000 or <800 kcal/day; female: >3500 or <500 kcal/day) [27]. Of the remaining 35589 participants at baseline, 5635 were diagnosed with diabetes by a blood test (Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%) [28] or previously diagnosed by a physician or on anti-diabetic medication. Together with 198 missing follow-up disease records, 5833 participants were excluded from this analysis (Fig. S1). As a result, 29517 participants with a median follow-up duration of 5.69 years until 21 September 2022 were included to explore the association of protein intake with risk of incident T2D. This study was approved by the ethical review board of the School of Public Health of Fudan University (IRB#2016-04-0586), and all participants signed the written informed consent.

Dietary macronutrient intakes

In SSACB, dietary data were collected for each participant at enrollment with a validated Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) and the inventory survey of household condiments. Reliability and validity of the FFQ have been assessed during the early stages of SSACB baseline survey by comparing discrepancy rates, Pearson/Spearman correlations, and Bland-Altman agreement analyses for food categories, and energy and macronutrient intakes. Although certain food categories observed lower reliability and validity in intake assessments, the overall correlations and agreement fell within acceptable ranges [27, 29], indicating that the used FFQ had acceptable validity and reproducibility and was applicable for SSACB studies to evaluate dietary patterns and nutritional health status in adults. Detailed methodological descriptions and evaluation results were provided in Appendix S1. At first, the China food composition tables (standard edition) [30] were used to calculate the macronutrient compositions of food items, weighing them with the average food consumption of Shanghai residents [31]. Secondly, food items in the FFQ were summarized into 17 food groups according to the characteristics of the dietary structure in Shanghai (plant protein sources including rice, refined wheat, whole grains, vegetables, fruits, soybeans, and nuts; animal protein sources including eggs, dairy, pork, beef, lamb and others, poultry, organ meats, freshwater fish, sea fish, and shellfish; and processed food sources of protein).

Ascertainment of Incident T2D

Incident T2D cases were identified according to the physician diagnosis or medication records obtained from the electronic information system, consisting of an electronic medical record system, a chronic disease management system, a cancer registry system, an infectious disease report system, and a death registry system.

Assessment of covariates

Demographic characteristics and lifestyle factors for each participant were collected face-to-face with standardized and validated questionnaires by trained investigators; anthropometric measurements, biomarkers, and B-mode ultrasonography of the hepatobiliary system were performed according to standard protocol by licensed physicians in the local hospitals at baseline.

A current smoker was defined as having smoked at least one cigarette per day for 6 months or longer. A current drinker/tea drinker was defined as having alcoholic drinks/teas at least three times per week for 6 months or longer. Physical activity was calculated based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF) [32], differentiating between walking, moderate intensity, and vigorous-intensity activities according to the estimated energy expenditure for each of them (3.3, 4.0, and 8.0 metabolic equivalents (METs), respectively), and MET-min/week was used as a unit of calculation. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) by height squared (m2). Central obesity was defined as waist ≥90 cm in males or ≥85 cm in females [33]. Hypertension was defined as self-reported hypertension or recorded systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg [34]. Hyperlipidemia was defined as total cholesterol ≥6.2 mmol/L or triglyceride (TG) ≥ 2.3 mmol/L or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥4.1 mmol/L or high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <1.0 mmol/L [35]. NAFLD was defined as the nondrinkers with fatty liver previously diagnosed by physicians or confirmed by B-mode ultrasonography at baseline.

Statistical analyses

Population characteristics were presented as mean ± standard deviations for normally distributed continuous variables, medians [interquartile ranges] for nonnormally distributed continuous variables, and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Differences in population characteristics by incidence of T2D were accordingly compared using Student’s t, Wilcoxon rank-sum, or Chi-square tests.

In SSACB, each participant’s follow-up time was defined as the duration between the entry to the cohort and the date of T2D occurrence or censor (death or end of follow-up), whichever occurred first. Variables that have been proved to be independent risk factors for T2D or with significant results of univariate analyses or top 10 variables in random forest importance selection (Fig. S2) were chosen as the covariates in the adjusted models. According to time-dependent concordance indexes (C-index), MODEL E was chosen as the basic model (Fig. S3), adjusted for age, sex, family history of diabetes, total energy intake, HbA1c, TG, waist, and hypertension at baseline. We adjusted baseline smoking status, drinking status, physical activity, and daily intake of fruit, carbohydrates, or fat to eliminate confounders in other models. The associations of various protein intake exposures with the risk of incident T2D were assessed using multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models, with hazard ratios (HRs) scaled per 1-percentage-point increment in the proportion of energy intake from total/plant/animal/processed food protein, and the potential non-linear associations were virtualized by restricted cubic splines (RCS). The P-nonlinear was estimated with a likelihood ratio test. The proportional hazards assumption of the piecewise Cox model was tested, and no clear evidence of violation was detected (Table S1). Leave-one-out models were built for substitution analysis. In addition, sensitivity analyses were conducted among the participants without cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer at baseline.

To minimize the differences in population characteristics except protein intake between adults with and without metabolic diseases at baseline. Propensity-score matching was used to identify participants with the most similar probability of hypertension, NAFLD, hyperlipidemia, or central obesity in the residents without these diseases at baseline. Propensity scores were obtained through random forest using the literature search-based variables (Table S2) [36,37,38,39,40]. Propensity-score matching used the nearest neighbor matching without replacement and within a caliper width of 0.02. Satisfactory matching was defined as the standardized mean difference <0.1 or variance ratio <2 for continuous variables [41], and no clear evidence of violation was detected (Fig. S4 and Table S3).

We considered a two-sided P < 0.05 statistically significant in all analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.5.

Meta-analysis on protein intake and incident T2D

We conducted a meta-analysis that incorporated our results from SSACB with the findings from previous cohort studies to evaluate the associations of protein intake with the risk of incident T2D in a broader population.

A literature search was conducted in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) and Web of Science (http://www.webofscience.com) on 27 February 2023 to identify the cohort studies that looked at the association of dietary protein with T2D (Table S4). In addition to electronic database searches, we manually screened the reference lists of included articles and key review papers to identify potentially eligible studies not captured by the initial search strategy. If the same cohort has been analyzed multiple times in different reports, the study provided more details were included. Studies were included if they (1) had a prospective cohort design, (2) investigated total, animal, or plant protein intake, (3) defined T2D incidence as the outcome, (4) reported the effect estimates (risk ratios (RRs), HRs, or odds ratios (ORs)) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and (5) described the adjustment for potential confounders. Extracted data included the first author’s name, publication year, country where the study was conducted, cohort name, study period (baseline survey time and follow-up duration/study end time), sample size, percentage of female participants, number of T2D cases, age at baseline, diet assessment, ascertainment of incident T2D cases, covariates in the maximally adjusted model, and effect estimates with corresponding 95% CIs. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale. The studies obtained scores of 4–6, regarded as medium quality, and those of 7 to 9 considered good quality [42].

For the pooled estimates across studies that compared the highest category of protein intake with the lowest category, the per unit protein daily intake increase was obtained using fixed/random-effects meta-analysis. RRs were used as the common measure of associations across studies, and HRs were considered equivalent to RRs. Study weights were calculated by the inverse of the variance of the logarithm of RR. I2 and Q tests were used to assess the heterogeneity of pooled estimates [43], and the fixed-effect model was selected when I2 < 50% and P ≥ 0.05. Egger’s test and funnel plots were used to assess publication bias for the primary analysis. Small-study effects were adjusted by PET-PEESE meta-regression. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to calculate the pooled estimates of the remaining studies by removing one study at a time to see whether the association depended on particular research.

In addition, dose-response meta-analyses were used to investigate associations between protein intake and risk of incident T2D. Firstly, the method proposed by Greenland et al. [44] was used to calculate the trend from the correlated logarithm of HRs across categories of protein intake, acquiring more than two exposure categories, the number of cases and person-years, the HR and corresponding 95% CI, and the mean or median protein intake for each category. Total protein intake was transformed to percentage energy (%E), using each category’s average daily energy intake, while animal and plant protein intakes were transformed to grams uniformly. Then, a two-stage, random-effect dose-response meta-analysis, modeling dietary protein intake via RCS with three knots [45], was used to explore the potential non-linear association of protein intake with the risk of incident T2D. Linear dose-response meta-analysis was conducted when the P-nonlinear ≥ 0.05. Two-sided P values of < 0.05, obtained for pooled results, were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.5.

Results

Cohort analyses

In SSACB, among the 29,517 residents without diabetes, the mean age was 55.4 years at baseline, and 1511 (5.1%) participants developed T2D during a median follow-up period of 5.69 years (95%CI: [5.69, 5.71]). The median protein intake was 61.4 g/d, and plant protein accounted for the majority (36.5 g/d). The participants who developed T2D in follow-up were older, less educated, physically active with shorter sleep durations, having a higher BMI and a family history of diabetes, and more likely to be a current drinker and married and having central obesity, hyperlipemia, hypertension, and having higher energy from carbohydrates (59.4% ± 10.1, P = 0.001), lower energy from fat (29.8% ± 9.0, P = 0.010) and protein (12.2% ± 2.4, P = 5.74E-8), compared with those without T2D in follow-up (Table 1).

Association of energy from total protein with risk of incident T2D

A U-shaped association (Fig. 1) between energy from total protein and risk of incident T2D (P-nonlinear = 0.017) was found with a protective range between 12.20%E and 16.85%E (cut-off point: 14.53%E). Compared to energy from protein between 14.50% and 15.10%, the risk of incident T2D for adults with energy from protein in the lowest quantile (≤10.60%, HR [95% CI]: 1.38 [1.03,1.85]) and the highest quantile (>17.00%, HR [95% CI]: 1.50 [1.04, 2.15]) were both higher (Table 2), and sensitivity analysis results among adults without cancer at baseline were similar (Table S5-1). However, among adults without CVD (Energy from protein: 12.6% ± 2.4), the risk of incident T2D for adults with energy from protein more than 17.00% was only marginally higher than those with energy from protein between 14.50% and 15.10% (HR [95% CI]: 1.43 [0.988, 2.08], Table S5-2).

HRs were scaled per 1-percentage-point increment in the proportion of energy intake from total protein. RCS analyses based on the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model were used to fit data, adjusted for age, sex, family history of diabetes, total energy intake (kcal/d), HbA1c (%), TG (mmol/L), waist (cm), and hypertension at baseline. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are filled by light blue. Cutoff values and points with a Hazard ratio (HR) equal to 1 are indicated by pink dotted lines and arrows, respectively.

After additional adjustments for the intake of carbohydrates or fat, the estimate for adults with energy from the protein in the highest quantile was no longer statistically significant. In contrast, the estimate for adults with energy from protein in the third quantile (11.70–12.90%) became statistically significant (Table 2). Isocaloric (1%E) replacement of protein with either carbohydrate (HR [95% CI]: 1.09 [1.01, 1.18]) or fat (HR [95% CI]: 1.11 [1.02, 1.20]) was associated with an increased risk of incident T2D for adults with a percentage of energy from protein between 12.20% and 16.85% (Fig. S5).

Associations of different food proteins with risk of incident T2D

RCS analyses (Table S6) did not find non-linear associations of protein sources with risk of incident T2D (all P-nonlinear > 0.05). Plant protein was associated with a reduced risk of incident T2D (HR per 1%E: 0.947, 95% CI: [0.900,0.996]), animal protein was associated with a reduced risk of incident T2D only when the intake of carbohydrate (HR per 1%E: 0.964, 95% CI: [0.932,0.998]) or fat (HR per 1%E: 0.969, 95% CI: [0.940,0.998]) was additionally adjusted, whereas processed food protein was not significantly associated with risk of incident T2D in all models (Table 3), and sensitivity analysis results among adults without cancer or CVD at baseline were similar (Tables S7-1 and S7-2). Replacing 1%E processed food protein with 1%E plant protein was found to be significantly associated with the reduced risk of incident T2D (HR [95% CI]: 0.945 [0.898, 0.995]) (Table S8).

Subgroup analyses of the association between total protein and risk of incident T2D

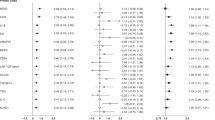

Subgroup analyses (Fig. 2) indicated the association of total protein with the risk of incident T2D differed by metabolic diseases, and the U-shaped associations remained significant in adults without metabolic diseases (all P-nonlinear < 0.05). In adults with hypertension (Fig. 2A), a U-shaped association (P-nonlinear < 0.001) with a narrower protective range (12.20–15.35%E) was found with a lower energy from protein (13.55%) at the lowest risk for incident T2D. When total protein intake >13.55%E, the protein was positively associated with the risk of incident T2D (HR per 1%E: 1.08, 95%CI: [1.004, 1.16]). In adults with NAFLD (Fig. 2B), total protein intake was associated with a reduced risk of incident T2D (HR per 1%E: 0.952, 95%CI: [0.910, 0.995]). In adults with hyperlipidemia (HR per 1%E: 0.981, 95%CI: [0.943,1.02]) or central obesity (HR per 1%E: 0.978, 95%CI: [0.943, 1.02]), no significant association between total protein and risk of incident T2D was found (Fig. 2C, D).

HRs were scaled per 1-percentage-point increment in the proportion of energy intake from total protein. Participants were divided into two subgroups via propensity-score matching, including with (dark red) and without (dark blue) A hypertension, B NAFLD, C hyperlipidemia, or D central obesity at baseline. Cox proportional hazards models were adjusted for family history of diabetes and HbA1c (%) at baseline.

Meta-analyses of associations between protein intake and risk of incident T2D

We identified a total of 1194 records, and fourteen reports (eighteen cohorts, including SSACB) met the inclusion criteria (Fig. S6) [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15, 19, 21, 46,47,48]. In total, 649638 participants and 53912 incident cases of T2D were used to analyze the associations of protein intake with the risk of incident T2D. Most cohort studies in Western countries obtained the dietary data at baseline from FFQ, with follow-up years longer than 10 and a sample size bigger than 10000 (Table S9). Only five cohorts (including SSACB) obtained the outcome data from the medical registration system. Fourteen studies were considered to have a low risk of bias (Table S10). In addition, cohort studies conducted in China had the lowest intake levels of total and animal protein and the highest intake levels of plant protein (Table S11).

Total protein was positively associated with the risk of incident T2D (RR [95%CI]: 1.06 [1.03, 1.09]), and the pooled heterogeneity was significant (I2 = 61%, P < 0.010) (Fig. 3A), might due to the proportion of females, different units to measure protein intake, and living on different continents (Table S12). Animal protein was positively associated with the risk of incident T2D (RR [95%CI]: 1.07 [1.04, 1.11]), and the pooled heterogeneity was significant (I2 = 78%, P < 0.010) (Fig. 3C), might due to the different units to measure protein intake and living on different continents (Table S12). Although publication bias (P = 0.011) of the association between animal protein and incident T2D was significant, the corrected (RR [95% CI]: 1.08 [1.03, 1.14]) and uncorrected results were similar (Fig. S7). After the removal of the study by Li and colleagues of Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study and clinical trials (WHI-OS-CT) [21] or the study by Chen and colleagues of Rotterdam Study (RS) [15], an inverse association of plant protein with incident T2D could be identified (Fig. S8).

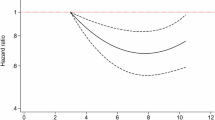

Seven cohorts (MDC, NHS, NHS II, HPFS, WHI-OS-CT, CHNS, and SSACB) [7, 10, 12, 21] were included in the further dose-response meta-analysis of total protein and incident T2D. A U-shaped association (P-nonlinear < 0.001) of total protein intake with risk of incident T2D was found with a substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 72.4%, P < 0.001) and the lowest pooled HR occurred at 15.10%E (Fig. 4). Six cohorts (including SSACB) [12, 21, 46] were included in the dose-response meta-analysis of animal protein and incident T2D, finding no significant linear association (P = 0.29), with a considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 80.4%, P < 0.001) (Fig. S9).

Data were pooled HRs [95% CIs], calculated by two-stage non-linear dose-response for meta-analysis based on RCS, with HRs were scaled per 1-percentage-point increment in the proportion of energy intake from total protein. Solid blue line denotes HR, dotted blue lines denote corresponding 95% CI, and gray solid line represents the HR equal to 1. Pink dotted lines and arrows indicate cutoff values and points with HR equal to 1.

Discussion

In our study, cohort analysis and dose-response meta-analysis suggested a U-shaped association between total protein intake and risk of incident T2D with similar optimal ranges. A linear inverse association of plant protein intake with risk of incident T2D was found in SSACB. Subgroup analyses indicated that the association of total protein intake with risk of incident T2D differed by metabolic diseases in SSACB; a U-shaped association with a narrower range of protective protein intake occurred in adults with hypertension, a linear inverse association was found in adults with NAFLD, whereas no significant association was observed in adults with hyperlipidemia or central obesity.

Interestingly, except for CHNS [7], no other cohort study in our meta-analysis directly supported the U-shaped association between total protein intake and risk of incident T2D, a finding obtained from our in-house cohort analysis and dose-response meta-analysis. However, most cohort studies [7, 9,10,11,12, 14, 15, 21] supported the conclusion in SSACB that total protein intake in the high quantile was associated with an increased risk of incident T2D. One explanation for these discrepancies might be that a lower average level of total protein consumption was observed in the cohorts from China than in the Western countries, providing more data on the association of low protein intake levels with the risk of incident T2D to complete the association curve. Another explanation might be the potential differences in dietary patterns and cooking methods of people from various continents, as suggested by the heterogeneity analysis in the general meta-analysis. More research is needed to elucidate the sources of heterogeneity.

Notably, the protein energy proposed for a balanced dietary pattern by The Chinese Dietary Guidelines (10–15%) [49] for a general population was narrower and lower than the range proposed in American (10–35%) [50] and Japan (18–49 years old: 13–20%, 50–64 years old: 14–20%, 65–74 years old: 15–20%) [5] for the prevention of non-communicable diseases or lifestyle-related diseases. Moreover, no acceptable macronutrient distribution range (AMDR) of dietary protein was documented in the newest version of Chinese dietary reference intakes (2013) [51]. In this study, the optimal protein energy range for T2D prevention was suggested to be from 12.20% to 16.85%, further supported by isocaloric replacement analysis of protein with either carbohydrate or fat, which, on the one hand, supported the nutrition claim by The Chinese Dietary Guidelines, and on the other hand, provided new population-based evidence to finalize the dietary protein acceptable macronutrient distribution range in China.

In addition to total protein intake, food sources of protein were also associated with the risk of incident T2D. Consistent with the results from a recent meta-analysis [45], an inverse association between plant protein and incident T2D was found in our study. Previous studies showed that soy proteins, either as intact soy protein or bioactive peptides derived from soybean [52, 53], might improve insulin resistance and lower blood sugar via α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. The accompanying fiber, magnesium, and vitamin intake could also slow the development of T2D [11, 15]. An inverse association was found between animal protein and incident T2D in SSACB, which did not agree with the results from current and previous meta-analyses [45]. The reasonably low level of animal protein intake observed in our cohort should be considered, as the reduced risk of T2D might not reflect animal protein per se but rather animal protein consumption habits. Indeed, intake doses greatly impacted the health effects of animal protein intake. Moreover, the sensitivity analysis results indicated that the associations of the highest quantile (>17.00%) proteins with the risk of incident T2D might be exaggerated in the whole population since the above association was only marginally significant in the participants without CVD. A possible explanation would be people with CVD might have a higher risk of developing T2D [54].

Although a Chinese expert consensus (15-20%) [6] and a national survey in India (16–20%) [55] recommended the optimal intake of protein energy for T2D prevention in adults with pre-diabetes, few cohort studies and limited RCTs looked at the adults with other metabolic diseases. In our study, the association of total protein intake with risk of incident T2D differed by metabolic diseases. The U-shaped associations could always be found in adults without hypertension, NAFLD, hyperlipidemia, or central obesity. Although the U-shaped association between total protein intake and risk of incident T2D could still be found in adults with hypertension, a lower optimal value and a narrower recommended range of protein energy was proposed, probably partially due to the long-term high-protein-induced inflammation, which has been proven to damage blood vessels and increase blood pressure [16, 56,57,58], and serum ferritin [59, 60], which could partially offset the beneficial effects of protein intake on glucose metabolism. For adults with NAFLD, an inverse association between total protein intake and risk of incident T2D was found without significant inflection points within the survey scope, suggesting a high-protein diet was recommended in our population to prevent incident T2D. Previous studies indicated that high-protein intervention could ameliorate hepatic steatosis through amino acid-induced Ubr1 activity and Plin2 ubiquitination (such as leucine and isoleucine) and improve glucose metabolism [61, 62]. Nevertheless, these findings should be interpreted cautiously, and further investigations in other populations and RCTs are warranted.

In adults with hyperlipidemia, although several studies suggested that high-protein diets and specific-food proteins might improve hypertriglyceridemia and elevate postprandial insulin response [25, 63], no significant association between total protein intake and risk of incident T2D was found in our study, probably due to the differences in protein compositions and the severity of hyperlipidemia, which might attenuate the improvements brought by macronutrient intake [23]. The previous reports regarding the association between total protein intake and risk of incident T2D were inconsistent in RCTs [64,65,66,67,68] and population-based studies among adults with obesity [19, 69], however, few studies have been conducted in China. Unfortunately, no significant association was found in our study. The duration of high-protein intake [66], subtypes of adiposity [70] and obesity severity [67], and other genetic factors [71] should be further explored in future research.

For the current study, the first strength was that this SSACB cohort with a decent sample size had a complete set of baseline anthropometric measurements and a diagnosable B-mode ultrasonography, which was a non-invasive, objective, and effective method to detect liver steatosis, regardless of the etiologies and comorbidities [72], allowing for more accurate diagnosis of NAFLD, and could obtain the new-onset T2D cases from the electronic information system. In addition, we used subgroup analysis based on propensity-score matching to differentiate the association of protein intake with the risk of incident T2D by metabolic diseases, and a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies was used to comprehensively examine the association between protein intake and risk of incident T2D. However, there are some limitations to be mentioned. First, although a wide range of risk and dietary factors for T2D were adjusted based on the random forest results and previous studies, the possibility of unmeasured confounders such as the duration and severity of disease and the comorbidities could not be ruled out. Second, although the FFQ was validated, the dietary intake could still be underestimated, and a single baseline measure of diet was unable to reflect changes in protein intake during the follow-up period. Third, a longer follow-up time would be more favorable to detect the health effects.

In summary, a U-shaped association between total protein intake and risk of incident T2D was found with a cutoff point of 14.53%E. Also, a protein intake of more than 15.35% of total energy was not recommended in adults with hypertension. In addition, plant protein would be beneficial for the Chinese in preventing T2D. Overall, our study provided population-based evidence for the protein intake recommendations for T2D prevention, and identifying characterized effects by metabolic diseases made a substantial step forward in constructing specialized lifestyle guidelines for T2D prevention.

Data availability

The datasets that support the findings of this study are available from the School of Public Health of Fudan University. Still, restrictions apply to the availability of these datasets, which were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. Datasets are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the School of Public Health of Fudan University.

References

International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 10th ed. Brussels, Belgium: 2021. Available at: https://www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed 20 May 2023.

Neuenschwander M, Ballon A, Weber KS, Norat T, Aune D, Schwingshackl L, et al. Role of diet in type 2 diabetes incidence: umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective observational studies. BMJ. 2019;366:12368.

Nutrition and Metabolic Management Branch of China International Exchange and Promotive Association for Medical and Health Care, Clinical Nutrition Branch of Chinese Nutrition Society, Chinese Diabetes Society, Chinese Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, Chinese Clinical Nutritionist Center of Chinese Medical Doctor Association. Chinese guidelines of medical nutrition therapy in diabetes (2022 edition). Chin J Diabetes Mellit. 2022;14:881–933.

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S68–S96.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan. Dietary reference intakes for Japanese 2020. Tokyo: Daiichi Shuppan; 2020.

Chinese Society of Endocrinology, Chinese Diabetes Society, Chinese Endocrinologist Association. Intervention for adults with pre-diabetes: a Chinese expert consensus (2023 edition). Chin J Diabetes Mellit. 2023;15:484–94.

Zhou C, Liu C, Zhang Z, Liu M, Zhang Y, Li H, et al. Variety and quantity of dietary protein intake from different sources and risk of new-onset diabetes: a Nationwide Cohort Study in China. BMC Med. 2022;20:6.

Virtanen HEK, Koskinen TT, Voutilainen S, Mursu J, Tuomainen TP, Kokko P, et al. Intake of different dietary proteins and risk of type 2 diabetes in men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Br J Nutr. 2017;117:882–93.

van Nielen M, Feskens EJ, Mensink M, Sluijs I, Molina E, Amiano P, et al. Dietary protein intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Europe: the EPIC-InterAct Case-Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1854–62.

Ericson U, Sonestedt E, Gullberg B, Hellstrand S, Hindy G, Wirfält E, et al. High intakes of protein and processed meat associate with increased incidence of type 2 diabetes. Br J Nutr. 2013;109:1143–53.

Shang X, Scott D, Hodge AM, English DR, Giles GG, Ebeling PR, et al. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1352–65.

Malik VS, Li Y, Tobias DK, Pan A, Hu FB. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:715–28.

Alhazmi A, Stojanovski E, McEvoy M, Garg ML. Macronutrient intake and type 2 diabetes risk in middle-aged Australian women. Results from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1587–94.

Sluijs I, Beulens JW, van der AD, Spijkerman AM, Grobbee DE, van der Schouw YT. Dietary intake of total, animal, and vegetable protein and risk of type 2 diabetes in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-NL study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:43–8.

Chen Z, Franco OH, Lamballais S, Ikram MA, Schoufour JD, Muka T, et al. Associations of specific dietary protein with longitudinal insulin resistance, prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: the Rotterdam Study. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:242–9.

Emdin CA, Anderson SG, Woodward M, Rahimi K. Usual blood pressure and risk of new-onset diabetes: evidence from 4.1 million adults and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:1552–62.

Mantovani A, Byrne CD, Bonora E, Targher G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of incident type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:372–82.

Tricò D, Mengozzi A, Baldi S, Bizzotto R, Olaniru O, Toczyska K, et al. Lipid-induced glucose intolerance is driven by impaired glucose kinetics and insulin metabolism in healthy individuals. Metabolism. 2022;134:155247.

Sugihiro T, Yoneda M, Ohno H, Oki K, Hattori N. Associations of nutrient intakes with obesity and diabetes mellitus in the longitudinal medical surveys of Japanese Americans. J Diabetes Investig. 2019;10:1229–36.

Li S, Wang Y, Ying Y, Gong Q, Lou G, Liu Y, et al. Independent and joint associations of BMI and waist circumference with the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Chinese adults: prospective data linkage study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;9:e39459.

Li J, Glenn AJ, Yang Q, Ding D, Zheng L, Bao W, et al. Dietary protein sources, mediating biomarkers, and incidence of type 2 diabetes: findings from the Women’s Health Initiative and the UK Biobank. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:1742–53. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-0368.

de Vos WM, Tilg H, Van Hul M, Cani PD. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut. 2022;71:1020–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326789.

Gadgil MD, Appel LJ, Yeung E, Anderson CA, Sacks FM, Miller ER. 3rd. The effects of carbohydrate, unsaturated fat, and protein intake on measures of insulin sensitivity: results from the OmniHeart trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1132–7.

Lamantia V, Sniderman A, Faraj M. Nutritional management of hyperapoB. Nutr Res Rev. 2016;29:202–33.

Bohl M, Bjørnshave A, Rasmussen KV, Schioldan AG, Amer B, Larsen MK, et al. Dairy proteins, dairy lipids, and postprandial lipemia in persons with abdominal obesity (DairyHealth): a 12-wk, randomized, parallel-controlled, double-blinded, diet intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:870–8.

Zhao Q, Chen B, Wang R, Zhu M, Shao Y, Wang N, et al. Cohort profile: protocol and baseline survey for the Shanghai Suburban Adult Cohort and Biobank (SSACB) study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e035430.

Willett W. Issues in analysis and presentation of dietary data. In: Willett W, editor. Nutritional epidemiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 305–32.

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46:S19–S40.

Gao J. Association of dietary patterns and physical activities with total body fat proportions and metabolic syndrome among middle-aged and elderly people: a cross-sectional study [D]. Shanghai: Fudan University Library; 2012.

Yang YX (editor). China food composition tables (standard edition). Beijing: Peking University Medical Press; 2005.

Yuan YQ, Li F, Meng P, You J, Wu M, Li SG, et al. Gender difference on the association between dietary patterns and obesity in chinese middle-aged and elderly populations. Nutrients. 2016;8:448.

Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, Stewart SM. Validity of the international physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:115.

Chinese Medical Association, Chinese Medical Journals Publishing House, Chinese Society of General Practice, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of General Practitioners of Chinese Medical Association, Expert Group of Guidelines for Primary Care of Endocrine System Disease. Guideline for primary care of obesity: practice version (2019). Chin J Gen Pract. 2020;19:102–7.

Chinese Medical Association, Chinese Medical Journals Publishing House, Chinese Society of General Practice, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of General Practitioners of Chinese Medical Association, Expert Group of Guidelines for Primary Care of Cardiovascular Disease. Guideline for primary care of hypertension: practice version (2019). Chin J Gen Pract. 2019;18:723–31.

Chinese Medical Association, Chinese Medical Journals Publishing House, Chinese Society of General Practice, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of General Practitioners of Chinese Medical Association, Expert Group of Guidelines for Primary Care of Cardiorascular Disease. Guideline for primary care of dyslipidemias: practice version (2019). Chin J Gen Pract. 2019;18:417–21.

Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:223–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-019-0244-2.

Yki-Järvinen H, Luukkonen PK, Hodson L, Moore JB. Dietary carbohydrates and fats in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:770–86.

Yuan S, Chen J, Li X, Fan R, Arsenault B, Gill D, et al. Lifestyle and metabolic factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2022;37:723–33.

Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2020;41:111–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455.

Blüher M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:288–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-019-0176-8.

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–107.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2012. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 20 May 2023. https://doi.org/10.2307/632432.

Higgins JPTTJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2022. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed 20 May 2023.

Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1301–9.

Zhao LG, Zhang QL, Liu XL, Wu H, Zheng JL, Xiang YB. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur J Nutr. 2019;58:1351–67.

Song Y, Manson JE, Buring JE, Liu S. A prospective study of red meat consumption and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and elderly women: the women’s health study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2108–15.

Sluik D, Brouwer-Brolsma EM, Berendsen AAM, Mikkilä V, Poppitt SD, Silvestre MP, et al. Protein intake and the incidence of pre-diabetes and diabetes in 4 population-based studies: the PREVIEW project. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109:1310–8.

Yuan S, Ming-Wei L, Qi-Qiang H, Larsson SC. Egg, cholesterol and protein intake and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: Results of repeated measurements from a prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:4180–6.

Chinese Nutrition Society. Chinese Residents’ Nutrition and Health Status Report 2022. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2022.

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of health and human services. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th ed. 2020. Available at https://www.DietaryGuidelines.gov. Accessed 20 May 2023.

Chinese Nutrition Society. Chinese dietary reference intakes 2013. Beijing: China Science Publishing & Media Ltd; 2014.

Chatterjee C, Gleddie S, Xiao CW. Soybean bioactive peptides and their functional properties. Nutrients. 2018;10:1211.

Hu S, Liu C, Liu X. The beneficial effects of soybean proteins and peptides on chronic diseases. Nutrients. 2023;15:1811.

Beckman JA, Paneni F, Cosentino F, Creager MA. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: part II. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2444–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht142.

Anjana RM, Srinivasan S, Sudha V, Joshi SR, Saboo B, Tandon N. Macronutrient recommendations for remission and prevention of diabetes in Asian Indians based on a data-driven optimization model: the ICMR-INDIAB National Study. Diabetes Care.2022;45:2883–91.

Zhang Y, Nie J, Zhang Y, Li J, Liang M, Wang G, et al. Degree of blood pressure control and incident diabetes mellitus in Chinese adults with hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e017015.

He J, Yu S, Fang A, Shen X, Li K. Association between protein intake and the risk of hypertension among chinese men and women: a longitudinal study. Nutrients. 2022;14:1276.

Mattson DL, Dasinger JH, Abais-Battad JM. Gut-immune-kidney axis: influence of dietary protein in salt-sensitive hypertension. Hypertension. 2022;79:2397–408.

Zhou J, Wang N, Wang D, Zhao R, Zhao D, Ouyang B, et al. Interactive effects of serum ferritin and high sensitivity C-reactive protein on diabetes in hypertensive patients. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2021;68:126824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2021.126824.

Wittenbecher C, Mühlenbruch K, Kröger J, Jacobs S, Kuxhaus O, Floegel A, et al. Amino acids, lipid metabolites, and ferritin as potential mediators linking red meat consumption to type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:1241–50. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.099150.

Zhang Y, Lin S, Peng J, Liang X, Yang Q, Bai X, et al. Amelioration of hepatic steatosis by dietary essential amino acid-induced ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2022;82:1528–1542.e10.

Markova M, Pivovarova O, Hornemann S, Sucher S, Frahnow T, Wegner K, et al. Isocaloric diets high in animal or plant protein reduce liver fat and inflammation in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:571–585.e8.

Uebanso T, Taketani Y, Fukaya M, Sato K, Takei Y, Sato T, et al. Hypocaloric high-protein diet improves fatty liver and hypertriglyceridemia in sucrose-fed obese rats via two pathways. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E76–84.

Chiu S, Williams PT, Dawson T, Bergman RN, Stefanovski D, Watkins SM, et al. Diets high in protein or saturated fat do not affect insulin sensitivity or plasma concentrations of lipids and lipoproteins in overweight and obese adults. J Nutr. 2014;144:1753–9.

Amankwaah AF, Sayer RD, Wright AJ, Chen N, McCrory MA, Campbell WW. Effects of higher dietary protein and fiber intakes at breakfast on postprandial glucose, insulin, and 24-h interstitial glucose in overweight adults. Nutrients. 2017;9:352.

Weickert MO, Roden M, Isken F, Hoffmann D, Nowotny P, Osterhoff M, et al. Effects of supplemented isoenergetic diets differing in cereal fiber and protein content on insulin sensitivity in overweight humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:459–71.

Goyenechea E, Holst C, van Baak MA, Saris WH, Jebb S, Kafatos A, et al. Effects of different protein content and glycaemic index of ad libitum diets on diabetes risk factors in overweight adults: the DIOGenes multicentre, randomized, dietary intervention trial. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:705–16.

Davis R, Bonham MP, Nguo K, Huggins CE. Glycaemic response at night is improved after eating a high protein meal compared with a standard meal: a cross-over study. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:1510–6.

Drummen M, Adam TC, Macdonald IA, Jalo E, Larssen TM, Martinez JA, et al. Associations of changes in reported and estimated protein and energy intake with changes in insulin resistance, glycated hemoglobin, and BMI during the PREVIEW lifestyle intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114:1847–58.

Chen Y, Zhou T, Sun D, Li X, Ma H, Liang Z, et al. Distinct genetic subtypes of adiposity and glycemic changes in response to weight-loss diet intervention: the POUNDS Lost trial. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:249–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02244-x.

Huang T, Ley SH, Zheng Y, Wang T, Bray GA, Sacks FM, et al. Genetic susceptibility to diabetes and long-term improvement of insulin resistance and β cell function during weight loss: the Preventing Overweight Using Novel Dietary Strategies (POUNDS LOST) trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:198–204.

Lee CM, Yoon EL, Nakajima A, Yoneda M, Toyoda H, Yasuda S, et al. A reappraisal of the diagnostic performance of B-mode ultrasonography for mild liver steatosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118:840–7.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the residents in Songjiang, Shanghai, who participated in this cohort study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Pujiang Program (21PJD005) and the Key disciplines in the 3-year Plan of Shanghai municipal public health system (2023-2025) (GWVI-11.1-42). The funding agencies had not been involved in the study design, data collection, analyses, interpretation, or manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MX designed the study, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. JZ conducted the study and helped write the manuscript. TY, YZ, and JD conducted the study. FL and BC provided methodological validation details to support the robustness of FFQ used in the SSACB study. YL designed the study and critically revised the manuscript. GH critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JZ and JD are employees of Nutrilite Health Institute in Shanghai, China. The conclusions and interpretations provided, based on the scientific data reviewed, are those of the authors and not of the employer and funding agencies of the study. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethical review board of the School of Public Health of Fudan University (IRB#2016-04-0586), and all methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent to participate

All participants provided the written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, M., Zheng, J., Ying, T. et al. Dietary protein and risk of type 2 diabetes: findings from a registry-based cohort study and a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr. Diabetes 15, 25 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-025-00380-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-025-00380-z