Abstract

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) presents significant clinical and therapeutic challenges due to its aggressive nature and generally poor prognosis. We initiated a Phase II clinical trial (ChiCTR1900027160) to assess the efficacy of a pioneering neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy regimen comprising programmed death-1 (PD-1) blockade (Toripalimab), nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel), and the oral fluoropyrimidine derivative S-1, in patients with locally advanced ESCC. This study uniquely integrates clinical outcomes with advanced spatial proteomic profiling using Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC) to elucidate the dynamics within the tumor microenvironment (TME), focusing on the mechanistic interplay of resistance and response. Sixty patients participated, receiving the combination therapy prior to surgical resection. Our findings demonstrated a major pathological response (MPR) in 62% of patients and a pathological complete response (pCR) in 29%. The IMC analysis provided a detailed regional assessment, revealing that the spatial arrangement of immune cells, particularly CD8+ T cells and B cells within tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS), and S100A9+ inflammatory macrophages in fibrotic regions are predictive of therapeutic outcomes. Employing machine learning approaches, such as support vector machine (SVM) and random forest (RF) analysis, we identified critical spatial features linked to drug resistance and developed predictive models for drug response, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 97%. These insights underscore the vital role of integrating spatial proteomics into clinical trials to dissect TME dynamics thoroughly, paving the way for personalized and precise cancer treatment strategies in ESCC. This holistic approach not only enhances our understanding of the mechanistic basis behind drug resistance but also sets a robust foundation for optimizing therapeutic interventions in ESCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) poses a significant global health challenge, marked by its aggressive nature and geographic variability in incidence and survival rates, ranking sixth in mortality worldwide [1]. High-incidence regions such as Eastern Asia, Eastern and Southern Africa, particularly northern China, Iran, and South Africa, contrast sharply with lower-risk areas such as North America and Western Europe [2, 3]. ESCC’s etiology is multifactorial, with key risk factors including tobacco use, alcohol consumption, poor nutrition, environmental toxins, and genetic predispositions that influence its pathogenesis [4, 5]. Standard treatment involves surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, tailored to the disease stage; however, the prognosis remains poor with a global five-year survival rate of 15-25% [6,7,8,9]. Neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy represents a strategic innovation in treatment, aiming to reduce tumor burden and improve surgical outcomes by reactivating the immune response against tumor cells [10].

The synergistic combination of programmed death-1 (PD-1) blockade, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel), and S-1 presents a compelling approach to modulating anti-tumor immunity within neoadjuvant settings for ESCC. PD-1 inhibitors have shown significant promise in reactivating exhausted T-cells, enabling them to effectively target and eliminate tumor cells [11]. Nab-paclitaxel, a formulation of paclitaxel bound to albumin nanoparticles, is noted for its enhanced permeability and retention effect, leading to increased drug accumulation at the tumor site. Additionally, it has been observed to reduce the number of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) within the tumor microenvironment (TME), further facilitating an immune-mediated attack on cancer cells [12]. S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine derivative, combines tegafur with modulators of its metabolism, enhancing the efficacy of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) while minimizing its systemic toxicity [13]. Its inclusion in this combination is based on its ability to inhibit thymidylate synthase, leading to DNA damage in proliferating tumor cells. Moreover, 5-FU, the active component of S-1, has been implicated in the induction of immunogenic cell death, thereby potentially enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapeutic agents [14]. The strategic combination of these agents is designed to exploit their individual mechanisms of action in a complementary manner. By doing so, it aims to dismantle the tumor’s protective barriers against the immune system, enhance the immunogenicity of the tumor cells, and promote a more potent and durable immune response. This approach not only targets the primary tumor but also addresses the systemic disease, offering a comprehensive strategy against ESCC in a neoadjuvant setting.

The TME of ESCC comprises a complex interplay among cancer cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), various immune cells including macrophages, T cells, and MDSCs, as well as endothelial cells surrounded by a dynamic extracellular matrix (ECM) [15]. This intricate network not only supports tumor growth and metastasis through the secretion of cytokines and growth factors but also facilitates immune evasion and ECM remodeling, enhancing tumor aggression and complicating therapeutic responses [16,17,18,19,20]. Understanding these interactions is crucial for developing targeted therapies that can effectively disrupt the pathological processes within the ESCC tumor microenvironment. Traditional methods of studying the TME, such as bulk tissue analysis, often fail to capture the spatial heterogeneity that is critical to understanding the complex interactions within the tumor landscape. These conventional techniques provide a generalized view that averages the cellular and molecular contents of tissue samples, obscuring crucial localized interactions and microenvironmental niches that significantly influence tumor behavior and therapeutic response [21]. Imaging Mass Cytometry (IMC) has emerged as a revolutionary tool that enables detailed spatial proteomic profiling of the TME. This technology combines the principles of mass cytometry with imaging capabilities, allowing for the simultaneous detection of multiple proteins at high spatial resolution [22,23,24]. IMC facilitates the visualization of cellular and molecular patterns within their native tissue contexts, providing insights into the cellular architecture and functional states of the TME. By preserving the spatial information and allowing for a cell-by-cell analysis, IMC helps delineate the heterogeneity and complexity of the TME, offering new avenues for targeted therapeutic interventions [25, 26].

The primary aim of this study is to elucidate the spatial proteomic landscape of ESCC using advanced IMC, aiming to identify TME features predictive of responses to chemo-immunotherapy. Secondly, we seek to leverage these insights to tailor targeted therapeutic strategies, thereby refining the precision of interventions in clinical trials. Lastly, we intend to develop a predictive tool that integrates spatial proteomic data with machine learning techniques to forecast individual responses to chemo-immunotherapy [27,28,29,30], enhancing personalized treatment plans in ESCC.

Results

Enhanced tumor response to neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy in ESCC: results from a phase II clinical trial

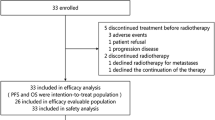

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy in patients with ESCC, focusing on surgical outcomes and molecular profiles. From November 2019 to July 2021, a cohort of 67 patients was evaluated for eligibility in this study. Sixty patients met the inclusion criteria and underwent neoadjuvant therapy (Fig. 1A). During the treatment phase, one patient developed severe atrial fibrillation, necessitating a modification in the treatment regimen. Additionally, three patients elected not to proceed with the surgical intervention. Post-neoadjuvant therapy, 56 patients underwent surgical procedures, achieving complete tumor resection (R0 resection) in 55 cases, indicative of no microscopic residual disease. Biopsies collected before and after treatment were subjected to comprehensive analysis using IMC, targeting 39 specific proteins (Fig. 1B and Table S1).

A Enrollment scheme for patient selection. This flowchart illustrates the process of evaluating and selecting patients for inclusion in the clinical trial. It details the initial number of patients assessed, the criteria for exclusion, and the final cohort of patients who met the inclusion criteria and proceeded with the neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy. B Treatment plan and sample collection points. This diagram presents the timeline of the treatment regimen administered to patients, highlighting both pre- and post-treatment phases. Key points of biopsy sample collection for molecular analysis are marked to indicate when samples were obtained for IMC. C Representative CT images showing therapeutic responses. This figure displays CT images of patients who exhibited varying responses to the neoadjuvant therapy. It categorizes the images into those showing good responses (grade 0 and 1) and poor responses (grade 2 and 3), providing visual documentation of the changes in tumor size and morphology post-treatment. D Patient characteristics. This figure summarizes the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patient cohort, including tumor staging and lymph node involvement. It also includes the distribution of therapeutic outcomes according to RECIST 1.1 criteria, showcasing the response rates within the treated group. E, F Kaplan–Meier survival plots showing the OS and PFS of 55 patients.

The assessment of the tumor’s response following neoadjuvant therapy was conducted in accordance with CAP/NCCN guidelines [31]. These guidelines advocate for a pathological evaluation to ascertain the efficacy of the treatment, which involves quantifying the proportion of tumor cells that survive the therapy. Post-neoadjuvant therapy, tumor shrinkage is systematically classified into several categories: complete response (no residual tumor, 0), partial responses (PR) (presence of residual tumor with a significant reduction, 1), stable disease (SD) (no appreciable change in tumor burden, 2), and progressive disease (PD) (an increase in either the size or number of tumors, 3). This classification facilitates a standardized approach to evaluating and documenting therapeutic outcomes. Figure 1C displays representative computed tomography (CT) images of patients who exhibited good (0 and 1 grade) and poor responses (2 and 3 grade) to the therapy, providing visual insights into the varied therapeutic outcomes observed within the cohort. Furthermore, the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The median age of the cohort was 60.4 years, with ages ranging from 45 to 75 years. The majority of the patients were male (87.27%) and were primarily diagnosed at stages III-IV, without metastasis but with significant lymph node involvement (85.45%). According to the RECIST 1.1 criteria, the therapeutic outcomes were as follows: PR in 60.0% of the patients, SD in 36.36%, and PD in 3.64%. This resulted in a disease control rate (DCR) of 96.36% across the patient population, detailed further (Fig. 1C and Table 2). Notably, a significant portion of the cohort experienced substantial tumor regression post-therapy: 52.73% (n = 29) achieved a major pathologic response (MPR), 29.09% (n = 16) a pathological complete response (pCR), 70.91% (n = 39) exhibited at least a 50% pathologic regression, as detailed in (Fig. 1D). When patients were stratified by the clinical outcome and the clinical characteristics of each group were analyzed, there was no significant enrichment of specific clinical characteristics observed across the various response groups (Fig. 1D). Adverse events (AEs) associated with the treatment are detailed in Table 3. The predominant AEs included alopecia, affecting 93.33% of patients, muscle soreness in 73.33%, fatigue in 58.33%, and anemia, leukopenia/neutropenia, and peripheral sensory neuropathy each occurring in 51.67% of cases. Serious AEs were reported in 11 patients (18.33%), with ten (16.67%) experiencing Grade 3 AEs and one (1.67%) encountering a Grade 4 AE. The most common severe AEs were leukopenia and neutropenia. There were no fatalities linked to the treatment (Table 3). It was evident that a significant proportion of these effects can be attributed to the chemotherapy component of the combination therapy. However, it is important to note that adverse effects typically associated with immune treatments, such as rashes, were observed in 33.67% of patients. Previous studies support the concept that while immune activation is effective against tumor cells, it can also induce collateral tissue responses, resulting in adverse effects [32]. However, in the current trial, immune-related adverse events did not correlate with a favorable response (Fig. S1). Additionally, the Kaplan–Meier curves illustrate the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for the cohort of 55 patients (Fig. 1E).

In conclusion, the findings of this study underscore the potential of neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy to improve surgical and molecular outcomes in patients with ESCC, aligning with our aims to assess both the efficacy and safety of this treatment approach.

Comprehensive spatial characterization of the pre- and post-adjuvant ESCC ecosystem at single-cell resolution

To dissect the spatial heterogeneity of the ESCC microenvironment while preserving the architecture of the ESCC ecosystem, we established a 40-marker IMC panel (39 protein markers and DNA) for the ESCC ecosystem (Fig. 2A, B), adapted from published protocols [25, 26]. Our 40-marker IMC panel covered markers for epithelial, endothelial, stromal cells, and various immune cells; the chemokine CXCL13; the proliferation marker Ki-67; and immune checkpoint-related markers including PD-1, programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), IDO1(Supplementary Table S1). Each antibody was validated by immunohistochemistry (IHC) before conjugation with heavy metals, and each metal-conjugated antibody was further validated by IMC (Fig. 2C).

A Schematic representation of IMC and analytical workflow. This panel illustrates the experimental setup and subsequent data analysis pipeline used in our study. It outlines the process from tissue sampling through to IMC acquisition and the computational strategies employed for data processing and image analysis. B IMC antibody panel design. This panel displays markers used in the study, showing both lineage and major functional markers for cell-type identification. C Single-color plot illustrating individual marker expression. This panel displays a representative single-color plot from IMC, showcasing the expression of a specific marker across tissue sections. This visualization helps in identifying the spatial distribution and intensity of the marker within the cellular microenvironment. D Heatmap of major and detailed cellular phenotypes. A dual-layer heatmap where the upper left section represents major cell types identified within the TME, and other sections delve into more granular subtypes, highlighting their expression profiles across different samples or conditions. The color of each tile represents the mean expression levels of the corresponding marker in cell type. E Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP). UMAP visualization depicting the multidimensional data reduced to a two-dimensional space, facilitating the discernment of clusters and patterns within the complex cellular landscape of the TME. F Filled bar chart comparing cellular compositions across different treatment response groups. This panel provides a filled bar chart that quantitatively compares the proportions of various cellular components within different response groups to therapy, illustrating shifts in cellular populations post-treatment. Each bar represents a sample, and the length of the colored segments represents the proportions of the corresponding cell type. G Distribution of cell subtypes among different response groups. This panel presents a refined visualization illustrating the distribution and frequency of specific cellular subtypes such as epithelial cells, lymphocytes, and myeloid cells, stratified by therapeutic response categories (good vs. poor). This detailed plot is vital in elucidating the cellular dynamics in response to treatment and their potential correlations with clinical outcomes. To quantify changes, fold differences are expressed on a logarithmic scale (log2), color-coded from blue (indicating a decrease, −5) to red (indicating an increase, +5), providing a visually intuitive representation of cellular fluctuations. Statistical significance is denoted by the size of squares: larger squares represent statistically significant changes (p-value < 0.05), while smaller squares indicate non-significant changes. Four comparative analyses are included to provide a comprehensive understanding of cellular alterations: Pre-treatment comparison between good and poor response groups (pre 0–1 vs. pre 2–3). Post-treatment comparison between good and poor response groups (post 0−1 vs. post 2−3). Longitudinal comparison within the good response group, from pre- to post-treatment (post 0−1 vs. pre 0−1). Longitudinal comparison within the poor response group, from pre- to post-treatment (post 2−3 vs. pre 2−3). Additionally, the frequency of each cell subset is depicted on the left side of the plot, providing a quantitative baseline against which changes can be measured. This multifaceted approach not only highlights the differential impacts of therapeutic interventions on various cell populations but also aids in identifying potential cellular biomarkers for predicting treatment efficacy.

In our spatial and cellular profiling of the ESCC ecosystem, we identified a variety of cellular constituents, which included Pan-cytokeratin+ (Pan-CK+) epithelial cells, CD31+ endothelial cells, αSMA+ myofibroblasts, Collagen I+ fibroblasts, and FAP+ fibroblasts. The immune cell landscape comprised CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes, CD14+ monocytes, and CD68+ macrophages, alongside lymphocytes including CD20+ B cells and CD3+ T cells (Fig. 2D, E).

Within the epithelial compartment, we observed Pan-CK+ E-Cad+ epithelial cells indicative of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [33], alongside other phenotypes such as Ki-67+ proliferating, IDO1+, IDO1+ S100A9+, and PD-L1+ epithelial cells, reflecting states of cellular proliferation, inflammation, and immune evasion, respectively. The presence of IDO1 and S100A9, both markers of inflammation, alongside PD-L1, a key immunosuppressive molecule, has been extensively documented in the literature [34,35,36].

Lymphocyte analysis revealed the existence of B cells, T cells, and natural killer (NK) cell subsets. Specifically, B cells included CD20+ cells, CXCL13+ B cells which are implicated in T and B cell recruitment [37], and proliferative Ki-67+ B cells. T cells were characterized by CD45RO+ CD4+ activated T cells, Foxp3+ Tregs, and CD38+ Foxp3+ Tregs [38]. Additionally, we identified Granzyme B+ effector CD8+ T cells, further indicating functional specialization within the T cell compartment. Notably, the proximity of different cellular subsets suggested potential microenvironmental interactions, complicating cell segmentation processes.

The macrophage meta-cluster was diverse, encompassing CD163+ macrophages, CD11b+ macrophages, C1QC+ macrophages (indicative of resident macrophage populations) [39, 40], PD-L1+ macrophages, CD11c+ HLA-DR+ antigen-presenting macrophages, SPP1+ and IDO+ SPP1+ macrophages, alongside LAMP3+ dendritic cells (DCs) and proliferative Ki-67+ macrophages. The expression of SPP1 and IDO1 suggests roles in immune modulation and inflammation [41,42,43], respectively, while LAMP3 denotes mature DCs, critical for effective antigen presentation [44].

In our study, we conducted a detailed analysis of cellular distributions across different therapeutic response groups, as depicted in Fig. 2F, which revealed notable distinctions. We assessed both pre- and post-treatment differences, and further stratified the results into good response (CAP/NCCN grade 0–1) and poor response (CAP/NCCN grade 2–3) categories.

In the Epithelial Cell Compartment: Post-treatment analysis showed a significant reduction in most epithelial cell subsets within the good response group (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1), aligning with expectations as chemotherapies and immunotherapies primarily target the tumor epithelial cells. Conversely, in the poor response group, only a fraction (3/7) of epithelial cell subsets demonstrated a decrease, specifically the proliferating and inflamed epithelial cells (Fig. 2G). Intriguingly, pre-treatment levels of S100A9+ epithelial cells were higher in the good response group (pre 0–1 vs. pre 2–3), possibly indicating a favorable prognosis for patients with inflammatory epithelial cells undergoing adjuvant therapy.

In the Fibroblast Compartment: The only differential subset observed was αSMA+ myofibroblasts, which were elevated in patients who exhibited a good response following adjuvant treatment. This suggests a potential role of myofibroblasts in mediating favorable therapeutic outcomes.

In the Lymphocyte Compartment: Surprisingly, most lymphocyte subsets did not show significant variations between the good and poor response groups either before or after treatment. The notable exception was the presence of overlapping CD8+ T cells and B cells in the good response group post-treatment (post 0–1 vs. post 2–3), which might indicate specialized immune features such as tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS). Conversely, a general increase in lymphocyte subsets was noted across both response groups from pre- to post-treatment samples. Specifically, B cells, proliferating B cells, and CXCL13+ B cells only increased in the good response group post-treatment (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1), underscoring the importance of these specific B cell subsets in mediating effective therapeutic responses. Tregs increased in the poor response group post-treatment (post 2–3 vs. pre 2–3), potentially contributing to immune suppression and a suboptimal therapeutic outcome.

In the Myeloid Cell Compartment: Although many myeloid cell subsets decreased post-treatment across both groups, this trend was less pronounced in the poor response group. Specifically, four myeloid cell subsets, including granulocytes and macrophages, were reduced in the good response group post-treatment (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1), whereas only granulocytes showed a decrease in the poor response group post-treatment (post 2–3 vs. pre 2–3). This pattern indicates that a reduction in myeloid cell suppression may be necessary for achieving a good therapeutic response.

These findings highlight the complex interplay of various cellular compartments in determining the outcome of cancer therapies and underscore the importance of personalized treatment strategies based on detailed cellular profiling.

Association of tertiary lymphoid structures’ cellular composition, functional markers, and surrounding milieu with clinical trial outcomes

Observations of significant B cell and T/B cell spatial features, suggestive of TLS, prompted a detailed examination of these entities. TLS, characterized by dense congregations of B and T cells, was hypothesized to play a pivotal role in therapeutic responses [45]. To investigate this, we employed a modified version of the previously developed patch algorithm [46], designed to identify cell clusters akin to tissue “patches” where B cells are notably condensed (Fig. 3A).

A Visualization of TLS organization and cellular composition via Mass cytometry by time of flight (MCD) and schematic representation. This panel illustrates the typical organization and cellular composition of TLS as detected by MCD. It features a detailed schematic diagram that highlights the spatial arrangement of B cells and T cells within these structures. Additionally, the panel describes how the patch algorithm is employed to identify TLS, focusing on the identification of densely organized B cells characteristic of these structures. B Quantification of TLS area. This graph depicts the variations in the size of B cell patches (representing TLS areas) post-treatment, comparing increases across both good and poor responder groups without significant differences between them. Each dot represents the mean frequency of cells belonging to TLS for a specific patient. C Cellular composition within TLS. Bar charts showing the proportions of key immune cell types within TLS, including the increased prevalence of CD8+ T/B cells in the good response group, emphasizing their potential role in mediating positive therapeutic outcomes. The Y-axis in the upper panel represents the overall frequency of cells within TLS, while the y-axis in the lower panel represents the relative frequency of the corresponding cell type within the four groups. D Statistical analysis of TLS composition. A t-test comparison illustrating the differences in the composition of immune cells within TLS between good and poor response groups, highlighting the suppressive roles of specific cell types in poor responders. Each dot represents the mean frequency of corresponding immune cells within TLS for a specific patient. E Functional markers within TLS. This panel presents changes in the expression of functional markers such as S100A9, PD-1, PD-L1, and HIF-1α within different cell populations of TLS, correlating these markers with response efficacy post-treatment. Each dot represents the mean fold change for a specific marker in a cell type within a certain comparison group, with the x-axis representing the log2 fold change and the y-axis representing the −log10 p-value. F Milieu composition analysis. Illustrates the composition of immune cells in the areas surrounding TLS, with a focus on the prevalence of activated CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells in the good response group, suggesting a favorable immune environment post-treatment. The bar chart in the upper panel represents the overall frequency of immune cells, while the lower panel represents comparisons between different groups. G Statistical evaluation of milieu composition. A t-test comparison of immune cell proportions in the milieu surrounding TLS between good and poor response groups post-treatment, indicating the influence of the local immune landscape on treatment outcomes. Each dot in the boxplot represents the frequency of a certain sample. Each dot in the boxplot represents the frequency of a certain sample.

Post-chemoimmunotherapy analysis revealed that TLS sizes increased significantly across both response groups; however, no size differences were observed between groups with good and poor responses (Fig. 3B). When assessing the cellular composition within TLS, CD8+ T/B cells were predominantly increased in the good response group post-treatment (post 0–1), underscoring their potential role in mediating favorable outcomes (Fig. 3C, D). Conversely, higher levels of Collagen I+ fibroblasts and PD-L1+ macrophages were noted in the poor response group, suggesting a suppressive impact on therapeutic efficacy (Fig. 3C, D).

Functional markers within TLS also mirrored these findings. In the good response group post-treatment (post 0–1 vs. post 2–3), a decrease in S100A9 expression in proliferating macrophages indicated reduced inflammatory activity, potentially beneficial for treatment outcomes. Moreover, the bad response group post-treatment (post 2–3 vs. pre 2–3) exhibited significant upregulation of PD-1 in lymphocyte subsets and PD-L1 in CD11b+ macrophages, along with increased HIF-1α in LAMP3+ dendritic cells, suggesting that heightened immune checkpoint activity and hypoxic responses might hinder effective adjuvant therapy (Fig. 3E).

Expanding our analysis to the milieu surrounding TLS, we employed a previously published method to define the adjacent areas for further examination [46] (Fig. 3F). Post-treatment, the good response group (post 0–1) showed a higher prevalence of CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells, indicative of an activated cytotoxic T cell environment conducive to positive outcomes. The proportions of NK cells were modestly increased in the group exhibiting a favorable response to treatment compared to those with a poor response post-treatment (post-scores of 0–1 versus scores of 2–3). NK cells are pivotal components of the anti-tumor immune response, particularly within the innate immune system [47, 48]. Previous research has demonstrated that anti-PD-1 therapies can potentiate the anti-tumor activities of NK cells [49]. Therefore, the observed elevation in NK cell counts in the group responding well to the combination therapy involving a PD-1 antibody aligns with established immunological mechanisms and supports the efficacy of such treatment strategies in enhancing innate immune responses against tumors (Fig. 3G). Post-treatment, no significant differences were observed between the groups exhibiting good (post-scores of 0–1) and poor responses (post-scores of 2–3). However, following combination therapy with PD-1 inhibitors, a marked increase in Treg cells was noted from pre- to post-treatment exclusively in the group with a poor response (from pre-scores of 2–3 to post-scores of 2–3). These findings suggest that it is not merely the presence of Treg cells, but rather their proportional increase post-treatment that may attenuate the efficacy of immunotherapy (Fig. 3G). This underscores the complex role of Treg cells in modulating immune responses during PD-1-targeted therapies and highlights the need for strategies that can modulate Treg dynamics to enhance therapeutic outcomes.

Please be aware that our IMC analysis did not include the full spectrum of dendritic cell (DC) markers; we identified only LAMP3-positive DCs within TLS. Additionally, there were no significant alterations observed in the LAMP3-positive DCs (Fig. S2). Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that other DC subsets might exhibit significant changes.

In conclusion, the differential dynamics and compositions of TLS and their surrounding milieu, particularly with respect to immune cell populations and functional markers, significantly influence the outcomes of chemo-immunotherapy, highlighting the complex interplay between TME and therapeutic efficacy.

Correlation of epithelial regional dynamics and immune region interactions with clinical trial outcomes

In our pursuit to understand broader spatial features beyond TLS, we explored the TME which comprises distinct regions such as the epithelial, immune, and fibrotic areas. Previous studies have shown that these regions exhibit variable interactions and responses to treatment [26]. Thus, we expanded our analysis to these specific regions, which are characterized by continuous cellular extensions. To facilitate this, we utilized a previously developed algorithm [50] (Fig. 4A) and further identified overlapping areas such as epi/immune and epi/fibrosis regions. We excluded the minor fibrosis/immune region from this analysis.

A Schematic illustration of TME regions with MCD overlay. This panel provides a detailed schematic illustration of the TME regions, including epithelial, immune, and fibrotic zones, along with intersecting areas such as epi/immune and epi/fibrosis. The illustration is augmented with an IMC image overlay to visually delineate the boundaries and characteristics of each region, facilitating a clear understanding of the spatial analysis methodology. B Comparative analysis of region sizes pre- and post-treatment. This graph displays the quantitative analysis of region sizes within the TME before and after treatment, categorized by response groups (good vs. bad). It highlights significant shrinkage in the epithelial areas in both groups post-treatment and provides a visual comparison to emphasize differences in region dynamics contingent on therapeutic outcomes. Each dot in the boxplot represents the size of a region for a specific sample. C Comparison of cellular composition within TME regions. This panel quantifies the cellular composition within different TME regions, comparing the proportions of key immune and stromal cell types before and after treatment across varying response groups. It focuses on identifying significant changes that correlate with therapeutic efficacy, such as increases in effector cells and decreases in suppressive cell populations. D Analysis of functional markers across TME regions. This graph illustrates changes in functional markers, including immune checkpoints and inflammatory markers, within the TME regions. It contrasts the alterations between pre- and post-treatment states across good and bad response groups, highlighting the regulatory dynamics that potentially influence treatment outcomes. Each dot represents the mean fold change for a specific marker in a cell type within a certain comparison group, with the x-axis representing the log2 fold change and the y-axis representing the −log10 p-value. E Comparison of milieu composition across TME regions. This panel explores the changes in the overall milieu composition of the TME regions, detailing shifts in cytokine profiles, growth factors, and other soluble mediators following therapy. It compares these milieu components across different regions and response groups, emphasizing how the local biochemical environment can modulate immune responses and influence clinical outcomes. Each tile represents the log2 fold change of the corresponding cell type, and only comparisons with t-test p-values < 0.05 are shown on the plot.

Initially, we assessed the area of these regions across different response groups. Notably, only the epithelial region demonstrated significant reduction post-treatment in both response groups (Fig. 4B), a surprising contrast to its larger pre-treatment size in the good response group. Other regions did not show significant changes in area between the groups. Within the epithelial region, frequencies of CD4+ T/B and CD4+ T/CD8+ T cells were higher pre-treatment in the good response group (pre 0–1 vs. pre 2–3). Post-treatment, suppressive cell populations such as αSMA+ and FAP+ fibroblasts, Tregs, and SPP1+ macrophages decreased in the good response group (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1), indicating a reduction in immunosuppressive cells.

In the immune region, close T/B cell interactions were more prevalent in the good response group post-treatment (post 0–1 vs. post 2–3). Post-treatment decreases in epithelial cells and macrophage subsets were observed in the response group (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1), alongside increases in T cell subsets. Although T cell subsets increased post-treatment in both the good and bad response groups, suppressive cells such as fibroblasts, Tregs, and macrophages only decreased in the good response group post-treatment.

Contrasting trends were observed in the fibrosis area, where Tregs were unexpectedly higher pre-treatment in the good response group (pre 0–1 vs. pre 2–3), and T cell subsets decreased post-treatment (post 2–3 vs. pre 2–3 and post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1). These results differ markedly from those in the epithelial and immune areas and may be attributed to the disorganized infrastructure characteristic of fibrotic regions. Few significant changes in cellular composition were noted in the epi/immune and epi/fibrosis interactions (Fig. 4C).

Focusing on functional marker differences, the most significant changes across various regions were observed when comparing post-treatment to pre-treatment in the good response group (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1, highlighted in orange), indicating that these marked alterations likely correlate with effective therapeutic response. Notably, most changes in functional markers involved the downregulation of immune checkpoints and inflammatory markers, underscoring their critical role in successful treatment outcomes (Fig. 4D). Conversely, upregulation of immune checkpoints in the bad response group (post 2–3 vs. pre 2–3) across different regions may contribute to poor therapeutic responses (Fig. 4D).

Continuing our investigation, we conducted a detailed millimeter-scale analysis of the regions to discern subtle features potentially impacting clinical outcomes. Notably, in patients exhibiting a favorable response post-treatment (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1), there was a pronounced enrichment of CD8+ T cell populations within the fibrotic milieu, including CD38+ T cells and CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells. Conversely, Tregs were predominantly enriched in the cohort demonstrating poor therapeutic response post-treatment (post 2–3 vs. pre 2–3).

Our comprehensive spatial and cellular analysis across diverse TME regions and their dynamic interactions with immune cells underscores a clear correlation between regional cellular alterations and clinical outcomes, with significant reductions in suppressive cell populations and modifications in immune checkpoints delineating the therapeutic responses observed.

Significance of T cell infiltration and interactions within immune and immune/epithelial overlapping regions for favorable clinical responses

To elucidate the impact of cellular interactions on clinical trial outcomes, we implemented an analytical approach adapted from a previously established methodology [25, 26]. Initially, a focal “central” cell was identified, around which the nearest ten cells were designated as neighboring cells to assess cell-cell interactions (Fig. 5A). This analysis was particularly focused on differentiating interactions across distinct regions, specifically the immune-exclusive and epithelial-immune (epi/immune) interfaces, to prevent data homogenization.

A Schematic illustration of cell–cell interaction analysis. This panel provides a schematic representation of the method used to analyze cell–cell interactions. A central cell is identified, and the interactions with its ten nearest neighboring cells are assessed to evaluate the local cellular communication dynamics, demonstrating the analytical framework employed. B Interaction patterns in immune regions. This graph shows the enriched T cell interactions within the immune region post-treatment, indicating an active immune response. Each tile represents the log2 fold change of the corresponding cell–cell interactions, and only comparisons with t-test p-values < 0.05 are shown on the plot. C Top up-regulated cell–cell interactions in immune regions. This graph depicts the significantly upregulated T cell interactions in the immune region of the good response group (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1, shown in orange), suggesting effective T cell infiltration and activation. Bar heights correspond to the log2 fold change of interactions between the respective comparison groups. D Interaction patterns in Epi/Immune regions. This panel illustrates the interaction patterns between T cells and fibroblasts within the epi/immune region, highlighting the interplay between epithelial and immune cells in this mixed cellular environment. Each tile represents the log2 fold change of the respective cell–cell interactions, and only comparisons with t-test p-values < 0.05 are shown on the plot. E Top up-regulated cell–cell interactions in Epi/Immune regions. This graph shows increased interactions between epithelial cells and T cells in the epi/immune region for the good response group, further emphasizing the importance of T cell presence and activity in mediating positive clinical outcomes. Bar heights correspond to the log2 fold change of interactions between the respective comparison groups.

In the immune-specific regions post-treatment, we observed a notable enrichment of T cell interactions as anticipated (Fig. 5B). This increase likely reflects an active immune response following therapeutic intervention. To further decode these complex interaction patterns, we ranked the most significantly upregulated cell-cell interactions in the immune region (Fig. 5C). In the good response group (post 0–1 vs. pre 0–1, depicted in orange), there was a marked increase in T cell interactions within the immune. This suggests enhanced T cell infiltration, a positive indicator of immune activation and potential therapeutic efficacy.

Conversely, within the epi/immune interface, interactions between T cells and fibroblasts were prevalent, illustrating the cross-talk between epithelial and immune cells in this mixed region (Fig. 5D). Similarly, in the epi/immune region, prominent interactions between epithelial cells and T cells were observed in the good response group, further indicating robust T cell infiltration and a potentially efficacious immune response (Fig. 5E).

These findings underscore the critical role of spatial and functional cellular interactions in shaping clinical outcomes, highlighting the intricate interplay between cellular components within the TME and their collective impact on therapeutic response.

Identifying response and resistance spatial features in the TME pre- and post-treatment using machine learning

Given the complexity of the TME, our objective was to discern which spatial features are pivotal in predicting treatment responses. We analyzed a comprehensive dataset encompassing cellular cluster frequencies, TLS, regional features, cellular interactions and major functional marker expression profiles. Our initial dataset comprised over 8000 features, including detailed metrics from cluster frequencies, TLS characteristics, and regional interactions.

To refine our analysis, we first eliminated features that exhibited excessive zero values across the samples. Subsequently, we addressed multicollinearity by excluding highly correlated features, opting to retain a single representative feature from each correlated group. This reduced our feature set to approximately 3000. These were further scrutinized using a random forest (RF) model to evaluate their importance in predicting treatment outcomes, as shown in Fig. 6A. Focusing on pre-treatment features, we identified the top three indicators of treatment response: PD-1 expression on CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells in the epi/immune intersection, CD4+ T/B cell ratios in both the epi/immune and purely epithelial regions. Notably, all these features were more pronounced in the good response group (pre 0–1 vs. pre 2–3), highlighting the significance of PD-1 expression in T and B cells within the epi-immune interface as critical determinants of a favorable treatment response. Conversely, the only feature predominantly observed in the poor response group was IDO1 expression on C1QC+ macrophages within the epi/fibrosis region, suggesting that this marker of macrophage inflammation serves as a negative predictor of treatment efficacy (Fig. 6B).

A Feature selection process for SVM analysis. This panel outlines the rigorous process used for the selection and refinement of spatial features from an initial set of over 8000. The selection criteria included the removal of highly correlated features, followed by the exclusion of features with excessive zero values across samples, resulting in a refined set of approximately 3000 features. This flowchart details each step of the feature reduction process, ensuring optimal input for machine learning analysis. B Importance of pre-treatment features in treatment response. This boxplot displays the importance of selected pre-treatment features identified by random forest analysis as critical predictors of treatment response. On the right are heatmaps showing scaled mean values by group. It highlights the top features, including PD-1 expression on CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T/B cells in specific TME regions, which are predominantly enhanced in the good response group. This visual representation underscores the predictive value of these immunological markers in forecasting treatment outcomes. C Relationship between the number of features and AUC. This line graph illustrates the relationship between the number of top features used in the predictive model and the resulting AUC values. It demonstrates that a minimal set of the top three features achieves an AUC of 92%, with marginal gains upon increasing the feature set to ten, which achieves an AUC plateau around 97%. This analysis emphasizes the efficiency and predictive power of using a reduced number of highly informative features. D Post-treatment feature importance. This boxplot compares the importance of various features post-treatment, paralleling the pre-treatment analysis in Fig. 6B. It evaluates how feature significance shifts following therapy and identifies any new predictors emerging as critical post-treatment. This comparison allows for an understanding of dynamic changes in the TME in response to therapy and their implications for ongoing treatment strategies. E Representative immunohistochemical staining of fibroblasts and macrophages in tumor organoid from post-treatment surgery samples.

We employed four distinct algorithms to predict treatment outcomes: random forest [51], generalized linear model [52], neural network [53], and shrinkage discriminant analysis [54]. Each algorithm demonstrated high area under the curve (AUC) values exceeding 95%, suggesting robust performance across different models with the selected features (Fig. 6C). Remarkably, the top 7 features achieved a plateau with an AUC of approximately 97–100% (Fig. 6C). Intriguingly, using only the top five features yielded an AUC of 95–100%, involving only six markers: Pan-CK (epithelial marker), CD45 (general immune marker), PD-1, CD4, CD8, and CD45RO (T cell markers), and CD20 (B cell marker). ROC analysis of the top five features showed that the random forest model gave the highest ROC of 0.94 (Fig. 6D).

To elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings associated with resistance and responses to treatment, we executed a detailed analysis of post-treatment samples employing RF methodology. This analysis aimed to pinpoint spatial features crucial in dictating the dichotomy between treatment responsiveness and resistance. In the cohort exhibiting a favorable response to treatment, the predominant spatial feature within the immune regions post-treatment was the frequency of CD8+ T cells and B cells. This finding suggests a robust immune activation in these regions, which correlates with a positive treatment outcome. Notably, this feature stood out as the top-ranking spatial characteristic specifically enriched in the good response group following treatment. Conversely, in patients characterized by a poor response, the dominant spatial feature was the expression of S100A9 in macrophages located within fibrotic regions (Fig. 6E). This observation underscores the detrimental impact of inflammatory macrophages in these areas, potentially contributing to an adverse treatment outcome. The recurrent identification of S100A9 expression as a critical feature in the bad response group highlights the significant role of fibrosis-associated inflammation in treatment resistance.

To further elucidate the role of S100A9+ macrophages and extend our observations to a larger cohort of ESCC patients, we performed single-cell RNA-seq analysis utilizing the publicly accessible dataset GSE145370 [55]. This comprehensive analysis delineated ten major cell types, including T cells, macrophages, B cells, NK cells, tissue stem cells, granulocytes, dendritic cells, mast cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and endothelial cells, based on their classical markers (Fig. S3A, B).

From an assembly of seven surgically resected ESCC tumors and corresponding adjacent normal tissues, we successfully isolated 113240 high-quality cells. Using cluster-specific markers, these cells were classified into the previously mentioned cell types, and their spatial distribution and interrelations were depicted through a UMAP plot (Fig. S3A, B). Our analysis corroborated the presence of the ten major cell populations and indicated a predominance of macrophages emanating from tumor regions (Fig. S3C).

Further re-clustering of the macrophage population was undertaken, which allowed us to identify eight distinct macrophage subsets (Fig. S3D, E). The distribution of these subsets across the samples was subsequently mapped (Fig. S3F). These macrophage clusters included infiltrating macrophages, C1QA/B+ macrophages, CD206+ macrophages, CTSK+ resident macrophages, SPP1+ macrophages, and proliferating macrophages.

A deeper investigation into the characteristics of these macrophage subsets revealed specific feature genes for each cluster (Fig. S3E). Notably, the expression of S100A9 was prominently highlighted (Fig. S3G), emphasizing its significant role within the macrophage subsets.

Additionally, leveraging the top 20 feature genes related to our study, we derived a gene set from the TCGA RNA expression matrix to calculate Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) scores for S100A9 macrophage. A survival analysis using the S100A9 macrophage GSVA scores demonstrated a significant association with patient survival outcomes (Fig. S3H). This extensive analysis not only sheds light on the heterogeneity within the macrophage population but also underscores potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for ESCC, enhancing our understanding of the tumor microenvironment and its implications for patient prognosis.

In conclusion, our extensive multi-omics analysis has revealed that distinct spatial features within the TME critically influence treatment outcomes. Notably, the expression of PD-1 on CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells, alongside the prevalence of CD8+ T and B cells in immunologically favorable regions, serve as robust predictors and determinants of positive treatment responses. In contrast, the expression of S100A9 in macrophages located within fibrotic zones is a significant marker predicting and driving adverse treatment outcomes. These findings underscore the pivotal role of spatial biomarkers in refining and enhancing therapeutic strategies for cancer treatment.

Discussion

The phase II study demonstrates the substantial efficacy of a neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy regimen integrating PD-1 blockade, nab-paclitaxel, and S-1 in ESCC, evidenced by high rates of major pathological response (MPR) and pCR. This regimen significantly enhances surgical outcomes and modulates the TME to overcome drug resistance. Advanced spatial proteomic analysis using IMC and machine learning has revealed pivotal spatial features within the TME that predict treatment responses and resistance. Key predictors of favorable treatment outcomes include elevated pre-treatment PD-1 expression on CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells, optimal CD4+ T/B cell ratios, and increased post-treatment CD8+ T and B cells within tertiary lymphoid structures. In contrast, markers such as IDO1 expression on C1QC+ macrophages and heightened S100A9 expression in macrophages within fibrotic regions indicate resistance. Moreover, leveraging machine learning techniques, we developed a robust predictive model for drug response with an impressive AUC of 97%. These findings underscore the importance of integrating spatial proteomic profiling and computational approaches to understand complex tumor dynamics and tailor personalized treatment strategies in cancer effectively [56,57,58].

The spatial proteomic data garnered from our investigation offer profound insights into the determinants of clinical outcomes in ESCC. Previous research has underscored the significance of TLS in determining treatment efficacy and prognosis in ESCC [59,60,61], however, we are the first to elucidate that, beyond mere cellular frequencies, the spatial characteristics and functional dynamics within the TLS critically enhance our understanding of therapeutic outcomes, such as the composition and functional status of TLS, as well as the surrounding milieu, emerge as critical factors influencing therapeutic responses. For instance, a post-treatment increase in CD8+ T and B cells within TLS was predominantly observed in the good response group (post 0–1), suggesting a pivotal role for these cells in mediating favorable outcomes. Conversely, the poor response group exhibited elevated levels of Collagen I+ fibroblasts and PD-L1+ macrophages, indicating a suppressive impact on therapeutic efficacy. CAFs have frequently been implicated in varying responses to immunotherapy treatments. CAFs are typically categorized into distinct subsets, such as myofibroblastic CAFs (myCAFs), inflammatory CAFs (iCAFs), and antigen-presenting CAFs (apCAFs). It has been observed that myCAFs and iCAFs generally correlate with poorer immunotherapy outcomes, whereas apCAFs tend to be associated with more favorable responses [62]. However, prior to our investigation, the specific impact of fibroblasts within TLS on immunotherapy outcomes had not been documented. Our study is pioneering in demonstrating the detrimental effects of collagen I-producing CAFs within TLS, based on findings from a real-world clinical study. Furthermore, macrophages play a dual role in the immunotherapy treatment landscape, having both positive and negative impacts [63]. PD-L1-expressing macrophages, in particular, have previously been reported to contribute positively to prognosis and therapy [64]. Nevertheless, our findings from an ESCC clinical trial indicate that PD-L1+ macrophages within TLS act as negative influencers. This adverse effect is likely due to the immune-suppressive actions of PD-L1+ macrophages on B and T cells within TLS, which are crucial for initiating immune responses in the TME. Consequently, immune suppression mediated by PD-L1+ macrophages in TLS is detrimental to the efficacy of immunotherapy.

The TME of ESCC can be stratified into distinct regions—epithelial, immune, and fibrotic—as delineated in previous work [26]. The roles of specific cellular subsets within these regions are pivotal in shaping therapeutic responses. In the epithelial region, we observed that higher pre-treatment frequencies of CD4+ T/B and CD4+/CD8+ T cells correlate with favorable outcomes (pre 0–1 vs. pre 2–3), aligning with existing literature on the critical role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in mediating immune responses to therapy [65].

Following treatment, there was a significant reduction in immunosuppressive cells including αSMA+ [66] and FAP+ fibroblasts [67, 68], Tregs [69], and SPP1+ macrophages [68] in the good response group. This reduction indicates a decrease in immunosuppressive elements, which are well-recognized barriers to immune therapy efficacy. Within the immune region, enhanced T/B cell interactions post-treatment were more prevalent in the good response group (post 0–1 vs. post 2–3), emphasizing the importance of cellular cooperation for effective immune response.

In the fibrotic region, disorganized immune cell configurations were noted, consistent with previous findings that fibrosis can impede immune responses [70]. Traditionally, fibroblast is viewed negatively in the context of immune response [67]. However, our observations of increased αSMA+ myofibroblast frequency in the good response group suggest that these cells may play a complex, potentially facilitative role in mediating positive treatment outcomes. This nuanced view challenges traditional perspectives and indicates that the contribution of myofibroblasts to immune modulation in cancer therapy warrants further investigation.

The application of IMC coupled with machine learning has enriched our understanding of the TME by delineating not only the heterogeneity within ESCC but also correlating spatial features with treatment outcomes. Critical spatial features determining response and drug resistance were identified, such as PD-1 expression on CD45RO+ CD8+ T cells at the epi/immune interface and CD4+ T/B cell ratios in both the epi/immune and purely epithelial regions. These features were significantly more pronounced in the good response group, underscoring the importance of PD-1 expression in T and B cells within these interfaces as crucial determinants of favorable treatment outcomes. In contrast, the expression of IDO1 on C1QC+ macrophages within the epi/fibrosis region was more common in the poor response group, highlighting this marker of macrophage inflammation as a negative predictor of treatment efficacy. In our previous paper, we also found that the inflammation usually caused a bad treatment response or prognosis [71]. A recent publication has observed a notable phenomenon regarding how tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) adapt to a stiffened and fibrotic TME in breast cancer. In response to the mechanical rigidity of the fibrotic TME, TAMs initiate a collagen biosynthesis program, which is predominantly driven by transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) signaling. This process of collagen production by TAMs contributes to creating a metabolically hostile environment for CD8+ T cells. This occurs as TAMs deplete environmental arginine, convert it to proline, and secrete ornithine, collectively impairing T cell functionality. Furthermore, the stiff and fibrotic nature of the TME not only physically restricts the infiltration of CD8+ T cells but also induces metabolic reprogramming of TAMs. These insights highlight that targeting the mechano-metabolic programming of TAMs could represent a valuable strategy to enhance the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy [72].

In conclusion, our study not only reaffirms the efficacy of combining PD-1 blockade with chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant treatment of ESCC but also underscores the transformative potential of spatial proteomic profiling in enhancing our understanding and overcoming drug resistance. Moving forward, integrating these insights into clinical practice could dramatically improve outcomes for ESCC patients, establishing a new paradigm in the precision of cancer therapy.

Limitations

The present study, while providing significant insights into the treatment dynamics of ESCC, is subject to several limitations that warrant discussion. Firstly, the scale of the trial was relatively limited. The predictive model we developed was based on data from a small cohort and has not undergone validation in a larger, phase III trial setting. This limitation is critical as it may affect the robustness and generalizability of our findings. Consequently, there is a substantial need for further research involving larger and more diverse patient populations to confirm whether the predictive capabilities of our model hold across broader clinical scenarios.

Secondly, our omics analyses, despite yielding valuable insights into the molecular underpinnings of treatment responses and resistance in ESCC, were not directly applied to guide tailored therapeutic strategies. For example, we identified an upregulation of S100A9-driven inflammation in macrophages among patients who exhibited resistance to treatment [19, 20]. This finding points to a potentially novel therapeutic target; however, we did not extend this observation to test or develop specific anti-inflammatory strategies that could be employed in clinical practice to overcome treatment resistance.

Moreover, the integration of our findings into clinical workflows poses another challenge. The translation of complex omics data into actionable clinical strategies requires not only validation through larger, multicentric studies but also the development of guidelines for implementing such strategies effectively within existing medical frameworks. Thus, while our study contributes to the foundational knowledge in this field, significant efforts are needed to ensure that these insights can be practically applied to enhance patient care in real-world settings.

In conclusion, while our study advances the understanding of ESCC treatment responses, the limitations highlighted must be addressed through continued research and clinical collaboration to ensure that such scientific discoveries lead to tangible improvements in oncologic care.

Materials and methods

Ethics

This study adhered to the ethical guidelines set forth by the Ethics Committee of the General Hospital of the People’s Liberation Army. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved. Additionally, the study was registered with the clinical trial registry under the number ChiCTR1900027160.

CAP/NCCN evaluation

These guidelines advocate for a pathological evaluation to ascertain the efficacy of the treatment, which involves quantifying the proportion of tumor cells that survive the therapy. Post-neoadjuvant therapy, tumor shrinkage is systematically classified into several categories by expert pathologists and clinical experts: complete response (no residual tumor, 0), PR (presence of residual tumor with a significant reduction, 1), SD (no appreciable change in tumor burden, 2), and disease progression (an increase in either the size or number of tumors, 3). This classification facilitates a standardized approach to evaluating and documenting therapeutic outcomes. Figure 1C displays representative CT images of patients who exhibited good (0 and 1 grades) and poor responses (2 and 3 grade) to the therapy, providing visual insights into the varied therapeutic outcomes observed within the cohort.

IMC section preparation

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients were sectioned at 4 µm using a HistoCore MULTICUT system (Leica, Germany). These sections underwent a heating process at 68°C for 1 h to facilitate dewaxing. Subsequently, sections were twice immersed in xylene at 68°C for 10 min intervals for complete dewaxing. Rehydration was achieved through sequential immersions in ethanol solutions of decreasing concentrations (95%, 85%, and 75%), each for 5 min at ambient temperature. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the sections in a sodium citrate buffer at 100°C for 30 min. After cooling to room temperature, sections were washed in PBS-TB (PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 and 1% BSA) twice for 5 min each. Blocking was carried out using SuperBlock (37515, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature. Sections were then washed thrice in PBS-TB before overnight incubation with a tailored antibody cocktail at 4 °C. The antibodies were conjugated to metals using Maxpar® X8 antibody labeling kits (Fluidigm), as detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Post-incubation, sections underwent three PBS-TB washes. Nuclear labeling was achieved with an Intercalator-Ir (201192B, Fluidigm) solution in PBS-TB (1.25 µM) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by two PBS-TB washes and a final rinse with ddH2O. Group 0–1 includes 7 samples, each featuring two regions of interest (ROIs) evaluated both pre- and post-intervention. Group 2–3 is comprised of 10 samples; within this group, 9 samples were analyzed with 2 ROIs each during the pre-treatment phase, while one sample was examined with 4 ROIs. In the subsequent post-treatment phase, there are 9 samples, each assessed with 2 ROIs.

IMC single-cell segmentation

Cell segmentation on IMC images was conducted using the pre-trained TissueNet algorithm, previously described in the literature. This algorithm processes data from two distinct imaging channels. The nuclear channel, typically stained with DAPI, delineates the cell nuclei, while the second channel, chosen here to highlight cellular membranes, marks the boundaries of individual cells.

IMC preprocessing and cell-type identification

Initially, marker expression data were transformed using a hyperbolic arc-sine function and trimmed at the 1st and 99th percentiles to define the range. Normalization of each channel was performed on a max-min basis. To correct for batch effects, we employed the Harmony algorithm (version 0.1.0) from the R package. Subsequent cell clustering was executed with Rphenograph (version 0.99.1), utilizing a 30-nearest-neighbors parameter. Initial clustering used lineage-specific markers including CD14, CD16, CD4, CD8, Collagen I, CD31, E-cadherin, CD45, CD163, CD68, CD11b, CD20, CD11c, CD15, CD3, FAP, CD57, Pan-cytokeratin and αSMA to establish major cell populations. The mean expression of each marker in every cluster was displayed on a heatmap. This expression pattern was then utilized for further annotation. Then a secondary, more refined clustering involved additional markers to delineate lymphocyte (including FoxP3, CD4, CD8, CXCL13, CD127, CD45, CD38, CCR7, CD20, Granzyme B, PD-1, Ki-67, CD45RA, CD3, CD45RO, CD57 and HIF1a), epithelial (including S100A9, HLAI, E-cadherin, IDO1, PD-L1, Ki-67, Pan-cytokeratin, HIF1a) and myeloid cells (including S100A9, CD16, CD14, CD45, IDO1, PD-L1, Ki-67, CD68, HIF1a, CD11b, CD11c, SPP1, HLA-DR, CD208, C1QC and CD163). Each sub-cluster was isolated from the total cohort and re-clustered using the same protocol. The resulting clusters were visualized in a heatmap to aid in cell-type annotation.

TLS and milieu detection

We use patchDetection from imcRtools packages to detect local accumulation of b-related cells. CD8T&B, B, CD4T&B, CXCL13+ B, and ProliferatingB were included in the TLS analysis. 20 μm was defined as the maximum distance between cells to be considered part of the TLS, and 30 was the minimal number of cells by which a TLS was defined. The TLS border was defined by a concave hull. Milieu is defined as cells located within the region by expanding the patch border by 20 μm.

Region and milieu identification

Region identification utilized strategies similar to those used for TLS detection. Three major region areas were defined as follows: Epithelial region involved EMT, Epithelial, ProliferatingEpithelial, IDO1+ S100A9+Epithelial, IDO1+Epithelial, S100A9+Epithelial and PD-L1+Epithelial. Fibrosis region involved FAP+Fibroblast, αSMA+Fibroblast and Collagen I+Fibroblast. The immune region involves all lymphocyte and myeloid cells. Regions were defined as containing at least 20 cells with a maximum distance of 20 μm between cells involved. Adjacent regions were merged together for downstream analysis. Regions were then expanded by 20 μm to form the milieus corresponding to about 2 cell diameters.

Cell–cell interaction metrics

The cell-cell interactions for each cell were captured using windows comprising the 10 nearest neighboring cells, as measured by Euclidean distance between their X and Y coordinates. These windows were then represented as a composition matrix encompassing all the defined cell types. The interaction strength of each region of interest (ROI) of the center cell with neighboring cells was calculated as the average value across all center cells. To identify statistically significant differences, comparisons between selected groups were performed using a two-tailed student’s t-test.

Multivariate modeling and variable importance

We derived four distinct sets of features for each ROI, encompassing cellular cluster frequencies, regional features, cellular interactions, and functional marker expressions. A total of 8401 features were derived for each ROI. Only features with ≥ 0 values in more than 10 ROIs were retained. We further reduced the feature space for multivariate models by identifying groups of highly correlated variables (Pearson correlation > 0.9) and randomly selecting one representative variable. We used an established feature selection algorithm to determine the most important features for treatment response prediction (implemented in the R package Boruta). The method involves repeatedly comparing true values with randomly shuffled features to identify which outperforms random data more often than would occur by chance. This process was repeated 10000 times to generate a binomial distribution of the number of times a given feature was regarded as important, and a final set of important variables was identified based on a threshold of P < 0.01. Taking only those features that outperformed randomly shuffled data more often than expected by chance, we plotted the distribution of their importance values to rank their importance.

We used AUC statistics to evaluate the predictive efficiencies of the confirmed features. The dataset was randomly split into training (70%) and test (30%). Four frequently used machine learning models, including random forest, generalized linear model, neural network, and shrinkage discriminate analysis model, were fitted to the training set (using cross-validation to optimize the model parameters). Predictions were made using the test data. This process was repeated 100 times for each feature set to calculate the mean value of AUC. Additional features were gradually incorporated into the model, starting with the top 3 most important features.

Single-cell RNA-sequencing data processing

The scRNA-seq dataset with accession ID GSE145370 was downloaded. The UMI count matrix was processed using the Seurat v4.0.1 R package to create a Seurat object. The downstream analysis focused on qualified cells that had a gene count between 200 and 6000 and a mitochondrial gene percentage below 25%.

To prepare the data for analysis, normalization was performed using the ‘NormalizeData’ function, and the top 2000 variable genes were identified using the ‘FindVariableFeatures’ function. To address any batch effects, the normalized data were integrated using the ‘FindIntegrationAnchors’ and ‘IntegratedData’ functions. The integrated data were then scaled and centered using the ‘ScaleData’ function, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using the ‘RunPCA’ function with the top 20 principal components selected.

For visualization and clustering, t-SNE and graph-based clustering were conducted using the selected principal components. The cell types were manually identified based on the expression patterns of feature genes.

The ESCC RNA-seq data, along with the corresponding clinical information, were downloaded from the TCGA database. To assess the cell-type signatures in each sample, GSVA was conducted using cluster-specific gene sets derived from scRNA-seq data. This analysis resulted in assigning cell-type signature scores to each sample, ranging from −1 to +1.

To evaluate the relationship between the GSVA scores and survival outcomes, Kaplan–Meier survival plots were generated using the survival and survminer packages in R. The GSVA scores were used as a predictor variable, and the survival time of the patients was considered the outcome variable. The log-rank test was employed to determine the statistical significance between the survival curves. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used to determine if the differences in survival curves were statistically significant.

Statistical analysis

The sample size for the clinical study was meticulously calculated based on preliminary data derived from a pilot study that examined similar endpoints. We utilized these preliminary data to estimate the expected effect sizes for key outcomes, particularly focusing on the differences in the tumor immune microenvironment following the combination therapy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy. To determine the required sample size, we employed a power analysis, ensuring a power of 80% and an alpha level of 0.05, which are standard for clinical research, to detect clinically meaningful differences. The effect size was determined based on the differences in immune cell infiltration and expression levels of immune checkpoints observed in the pilot study. Using the software G*Power, we input these parameters along with the estimated effect sizes to calculate the minimum necessary sample size. Additionally, we accounted for potential dropouts and non-compliance by increasing the sample size by 20%. This adjustment was intended to maintain the integrity and statistical validity of the study results under real-world conditions. Statistical tests were selected based on the appropriate assumptions for the data distribution and variability characteristics. A two-tailed t-test was used to identify differences in cell proportions and function marker expression between the two groups. A p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Data availability

The IMC data can be accessed via OMIX/OMIX006370.

Code availability

Please note that the IMC analysis in this study does not involve the original code. To access the original codes used, please refer to the “Methods” section and the respective references provided. If you require any additional information to reanalyze the data presented in this paper, please contact the corresponding author directly.

References

Uhlenhopp DJ, Then EO, Sunkara T, Gaduputi V. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer: update in global trends, etiology and risk factors. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1010–21.

Liu CQ, Ma YL, Qin Q, Wang PH, Luo Y, Xu PF, et al. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in 2020 and projections to 2030 and 2040. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14:3–11.

Li J, Xu J, Zheng Y, Gao Y, He S, Li H, et al. Esophageal cancer: epidemiology, risk factors and screening. Chin J Cancer Res. 2021;33:535–47.

Deybasso HA, Roba KT, Nega B, Belachew T. Dietary and environmental determinants of oesophageal cancer in arsi zone, oromia, central ethiopia: a case-control study. Cancer Manag Res. 2021;13:2071–82.

Gao YB, Chen ZL, Li JG, Hu XD, Shi XJ, Sun ZM, et al. Genetic landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1097–102.

Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Cooke D, Corvera C, Das P, et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 2.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:393–422.

Kitagawa Y, Uno T, Oyama T, Kato K, Kato H, Kawakubo H, et al. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2017 edited by the Japan Esophageal Society: part 1. Esophagus. 2019;16:1–24.

Lordick F, Hölscher AH, Haustermans K, Wittekind C. Multimodal treatment of esophageal cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:177–87.

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49.

Topalian SL, Taube JM, Pardoll DM. Neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade for cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2020;367.

Jiang Y, Chen M, Nie H, Yuan Y. Pd-1 and pd-l1 in cancer immunotherapy: clinical implications and future considerations. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15:1111–22.

Chen Y, Liu R, Li C, Song Y, Liu G, Huang Q, et al. Nab-paclitaxel promotes the cancer-immunity cycle as a potential immunomodulator. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11:3445–60.

Saif MW, Syrigos KN, Katirtzoglou NA. S-1: a promising new oral fluoropyrimidine derivative. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:335–48.

Kozai H, Ogino H, Mitsuhashi A, Nguyen NT, Tsukazaki Y, Yabuki Y, et al. Potential of fluoropyrimidine to be an immunologically optimal partner of immune checkpoint inhibitors through inducing immunogenic cell death for thoracic malignancies. Thorac Cancer. 2024;15:369–78.

Zou G, Anwar J, Pizzi MP, Abdelhakeem A. Unraveling the intricacies of neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive single-cell perspective. J Thorac Dis. 2024;16:826–8.

Pei L, Liu Y, Liu L, Gao S, Gao X, Feng Y, et al. Roles of cancer-associated fibroblasts (cafs) in anti- pd-1/pd-l1 immunotherapy for solid cancers. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:29.

Fang J, Lu Y, Zheng J, Jiang X, Shen H, Shang X, et al. Exploring the crosstalk between endothelial cells, immune cells, and immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment: new insights and therapeutic implications. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14:586.

Di Martino JS, Akhter T, Bravo-Cordero JJ. Remodeling the ECM: implications for metastasis and tumor dormancy. Cancers. 2021;13.

Che G, Yin J, Wang W, Luo Y, Chen Y, Yu X, et al. Circumventing drug resistance in gastric cancer: a spatial multi-omics exploration of chemo and immuno-therapeutic response dynamics. Drug Resist Updat. 2024;74:101080.

Bao X, Li Q, Chen D, Dai X, Liu C, Tian W, et al. A multiomics analysis-assisted deep learning model identifies a macrophage-oriented module as a potential therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 2024;5:101399.

Kiessling P, Kuppe C. Spatial multi-omics: novel tools to study the complexity of cardiovascular diseases. Genome Med. 2024;16:14.

Baharlou H, Canete NP, Cunningham AL, Harman AN, Patrick E. Mass cytometry imaging for the study of human diseases-applications and data analysis strategies. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2657.

Ji Y, Sun D, Zhao Y, Tang J, Tang J, Song J, et al. A high-throughput mass cytometry barcoding platform recapitulating the immune features for HCC detection. Nano Today. 2023;52:101940.

Rörby E, Adolfsson J, Hultin E, Gustafsson T, Lotfi K, Cammenga J, et al. Multiplexed single‐cell mass cytometry reveals distinct inhibitory effects on intracellular phosphoproteins by midostaurin in combination with chemotherapy in AML cells. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2021;10:7.

Du J, Zhang J, Wang L, Wang X, Zhao Y, Lu J, et al. Selective oxidative protection leads to tissue topological changes orchestrated by macrophage during ulcerative colitis. Nat Commun. 2023;14:3675.

Sheng J, Zhang J, Wang L, Tano V, Tang J, Wang X, et al. Topological analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma tumour microenvironment based on imaging mass cytometry reveals cellular neighbourhood regulated reversely by macrophages with different ontogeny. Gut. 2022;71:1176–91.

Shao W, Shi H, Liu J, Zuo Y, Sun L, Xia T, et al. Multi-instance multi-task learning for joint clinical outcome and genomic profile predictions from the histopathological images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2024;43:2266–78.

Shao W, Zuo Y, Shi Y, Wu Y, Tang J, Zhao J, et al. Characterizing the survival-associated interactions between tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and tumors from pathological images and multi-omics data. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2023;42:3025–35.

Shao W, Liu J, Zuo Y, Qi S, Hong H, Sheng J, et al. Fam3l: feature-aware multi-modal metric learning for integrative survival analysis of human cancers. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2023;42:2552–65.

Hamamoto R, Koyama T, Kouno N, Yasuda T, Yui S, Sudo K. et al. Introducing AI to the molecular tumor board: One direction toward the establishment of precision medicine using large-scale cancer clinical and biological information. Exp Hematol Oncology. 2022;11:82.

Health Commission Of The People’s Republic Of China N. National guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of esophageal carcinoma 2022 in China (English version). Chin J Cancer Res. 2022;34:309–34.

Bottlaender L, Amini-Adle M, Maucort-Boulch D, Robinson P, Thomas L, Dalle S. Cutaneous adverse events: a predictor of tumour response under anti-pd-1 therapy for metastatic melanoma, a cohort analysis of 189 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:2096–105.