Abstract

Background

To retrospectively investigate the developmental outcomes at 3 years of age in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) using a multicenter collaborative research approach.

Methods

We evaluated patients with CDH and no other malformations born between 2010 and 2016 in seven facilities in the Japanese CDH Research Group. The developmental quotient (DQ) at 3 years of age was evaluated using the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development 2001, the most standardized scale in Japan. Factors associated with a DQ score < 85 were also analyzed.

Results

Of 196 patients, developmental assessments at 3 years of age were performed in 132 patients (67%). Among these, 99 patients (75%) had a DQ score ≥ 85, 25 (19%) had a DQ score between 70 and 84, and 8 (6%) had a DQ score < 70. Multivariate analysis showed that the observed/expected lung area-to-head circumference ratio was an independent predictor of a DQ score < 85, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.62 (95% confidence interval: 0.40–0.96; p = 0.03).

Conclusion

Generally, isolated CDH is associated with good developmental outcomes for survivors, even after intensive care. However, there is a risk of neurodevelopmental impairment if pulmonary hypoplasia is present.

Impact

-

This research highlights the observed/expected lung area-to-head circumference ratio (o/e LHR) as a crucial indicator to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes in 3-year-old children diagnosed with isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH).

-

Our results provide robust evidence from a large multicenter cohort, emphasizing the importance of o/e LHR in early risk stratification and prolonged neurodevelopmental follow-up.

-

These findings highlight the need for comprehensive management and tailored follow-up care in CDH patients, potentially improving clinical protocols and enhancing the quality of life and outcomes for affected children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is characterized by herniation of the abdominal contents into the thorax. Despite advances in neonatal intensive care and surgical management, CDH continues to cause significant mortality and morbidity.1,2,3 This serious congenital anomaly leads to herniation of abdominal organs, such as the stomach, intestines, and liver, into the thoracic cavity, resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia and pulmonary vasculature dysplasia.4 The combination of these conditions with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of CDH.5,6,7

Recent advances in neonatal care and surgical management have significantly improved survival rates for patients with CDH.8,9 However, as survival rates have increased, neurocognitive disability and decreased functional outcomes in CDH survivors have become an issue.10,11 The neurodevelopmental outcomes of CDH patients represent an important clinical concern.

Parents of children with CDH are often concerned about the long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of their children. Studies have investigated developmental outcomes and predictors in CDH patients, indicating that these patients have a significant risk of cognitive and motor impairments, with prevalence rates ranging from 16% to 80%.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 The predictors of postnatal neurodevelopmental disorders (NDI) include the use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and the need for oxygen supplementation after 30 days of age, in addition to prenatal predictors, such as disease severity and gestational age at delivery. Decreased neuromuscular tone was also a predictor of NDI in several studies.13,15,22,23 However, these studies vary in the outcome domains that were measured, methodologies, and patients’ backgrounds (e.g., isolated CDH or non-isolated CDH, defined as CDH with additional congenital anomalies), contributing to the heterogeneity in the prevalence of NDI. Distinguishing between isolated and non-isolated CDH is crucial, as children with non-isolated CDH experience a higher incidence of NDI and have various chromosomal and structural abnormalities.24,25,26,27,28 Additionally, most studies involved univariate analysis because of the small number of patients, and even when multivariate analysis was performed, there were concerns about the validity of the analysis because of the small sample size.29,30 Therefore, we considered that the predictors of NDI in patients with CDH require multivariate analysis, with a sufficient number of patients and minimal heterogeneity in the patients’ backgrounds.

The aim of this study was to investigate the neurodevelopmental outcomes of patients with isolated CDH at 3 years of age using a Japanese multicenter research database, and to retrospectively examine whether disease severity is associated with NDI. We hypothesized that using a larger dataset in the analysis would clarify the impact of CDH severity on developmental outcomes, and lead to improved prognostic accuracy and family counseling.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

This study was part of the initiatives by the Japanese Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group (JCDHSG) and was a retrospective cohort analysis to evaluate the neurodevelopmental outcomes at 3 years of age in children with isolated CDH. The JCDHSG database includes approximately 30% of all CDH cases in Japan and data has been collected for demographics, laboratory and imaging findings, perinatal and postnatal treatments, and outcomes since its inception in 2011.31,32

This study enrolled patients with CDH born between 2010 and 2016 who were registered from participating facilities, with routine developmental assessments at age 3 years. We excluded patients with congenital malformations other than CDH or known chromosomal or genetic abnormalities. Patients who died before 3 years of age or patients without developmental assessment at 3 years of age were also excluded. Strategies for perinatal management and postnatal intensive care were not standardized across centers, and instead, followed the standards at each center.

Variables

We extracted the following detailed data from the JCDHSG database: gestational age, birth weight, 5-min Apgar score, sex, laterality of CDH, defect size of the CDH, liver-up status (defined as more than one‐third of the height of the left thoracic space occupied by the liver),33,34 thoracic position of the stomach,34 and umbilical arterial blood pH, duration of oxygen use, mechanical ventilation duration, nitric oxide therapy duration, age at surgery, length of hospital stay, use of pulmonary vasodilators, ECMO use, and home medical care requirements at discharge. Additional data regarding the prenatal diagnosis of CDH, presence of polyhydramnios, fetal hydrops, observed/expected lung-to-head ratio (o/e LHR),35,36,37 fetal treatment for CDH, place of birth, mode of delivery, multiple gestation, and prenatal steroid administration were also included. In this study, fetal ultrasound findings such as the observed/expected lung-to-head ratio (o/e LHR), liver herniation, and stomach herniation into the thoracic cavity were based on data measured at the initial assessment.

Small for gestational age was defined as less than 10% of both height and weight compared with Japanese infant standards.38

The position of the stomach was categorized as follows: grade 0, abdominal; grade 1, left thoracic; grade 2, less than half of the stomach herniated into the right chest; and grade 3, more than half of the stomach herniated into the right chest.34 Liver-up and the stomach position were only counted in patients with left CDH.

Developmental assessment

To evaluate the neurodevelopmental outcomes, children with CDH who survived were assessed using the Kyoto Scale of Psychological Development 2001 (KSPD) at the chronological age of 36–42 months.39,40 The KSPD is a standardized and validated developmental test specifically designed for Japanese children. This test measures the developmental quotient (DQ) across three domains: postural-motor, cognitive-adaptive, and language-social. The overall DQ score was calculated by averaging the scores from these three categories. This follow-up protocol classifies developmental function as normal (DQ score ≥ 85), subnormal (DQ score 70–84), or delayed (DQ score < 70), with a DQ score < 70 indicating a high risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.

These variables were carefully chosen to explore their association with neurodevelopmental outcomes, specifically focusing on factors related to a DQ score < 85. We defined NDI as an overall DQ score < 85.

Statistical analysis

We reported median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and number (percentage) for categorical variables. The analysis stratified children with CDH into two groups by the DQ score as with and without NDI. We also investigated the association between variables associated with NDI. We used the Mann–Whitney U test, and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for the univariate analysis. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictors of NDI. Among various indices that refer to disease severity, we chose o/e LHR because this is a validated indicator of disease severity35,36,37 and can be used in the prenatal period for perinatal counseling. Additionally, we selected ECMO use and tube feeding at discharge as potential confounders, in accordance with previous studies.21,41 p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0. (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and Excel (Microsoft 365; Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA) for all statistical analyses.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee of Kanagawa Children’s Medical Center granted approval for this study (approval number 2022-96). Owing to the study’s retrospective design and the use of de-identified data, the requirement for signed informed consent was waived. Study details were published on our institution’s website, allowing for opt-out participation. This study was performed with strict adherence to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical guidelines for medical and health research involving human subjects.

Results

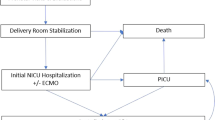

We recruited 346 CDH patients in this study. The patient inclusion flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. First, 122 patients were excluded owing to comorbid congenital malformations, including congenital heart diseases (n = 55), central nervous system structural abnormalities (n = 9), and congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (n = 11). Twenty seven of them had been diagnosed with chromosomal or genetic abnormalities: Trisomy 18 (n = 5), Cornelia de Lange syndrome (n = 3), Pallister–Killian syndrome (n = 2), Noonan syndrome (n = 2), Trisomy 13 (n = 2), Gorlin syndrome (n = 1), Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (4p deletion syndrome) (n = 1), Simpson–Golabi–Behmel syndrome (n = 1), Opitz syndrome (n = 1), karyotype 47, XY, +mar (specific type if known) (n = 1), Fryns syndrome (n = 1), Apert syndrome (n = 1), Tetrasomy 9p (n = 1), chromosomal deletion 46, Y, X, del (p22.32) (n = 1), chromosomal translocation 46, XY, der (21)t(1;21)(q42.3;q22.2) (n = 1), mosaic karyotype 46, X, +mar(10)/45, X (specific type if known) (n = 1), Turner syndrome (n = 1), and partial trisomy of chromosome 14 (n = 1). Of the 122 CDH patients who also had congenital malformations, 54 died by the age of 3, giving a mortality rate of 44.3%.

Second, among the 224 isolated CDH patients, we excluded 28 who died before reaching 3 years of age, resulting in a mortality rate of 12.5%.

Third, we also excluded 64 patients who had not undergone developmental assessments at 3 years of age. There were no differences in background characteristics other than tube feeding at discharge between patients with and without developmental assessment (Supplemental Table). After excluding the indicated patients, 132 remained as study patients. Among them, 99 demonstrated normal developmental progress, with DQ scores ≥ 85. There were 25 children with subnormal development, with DQ scores ranging between 70 and 84, and 8 children with delayed development, with DQ scores < 70. Collectively, these results indicated that just over half of the children in the patient population had normal DQ scores, while 25% experienced some degree of developmental delay (Fig. 1).

Comparisons of patients with DQ scores ≥ 85 and < 85 are shown in Table 1.

The timing of the fetal ultrasound measurements for the o/e LHR, liver herniation, and stomach herniation into the thoracic cavity was at a median (interquartile range) gestational age of 30.6 weeks (27.2–34.0 weeks). Fetal treatment (p = 0.001), o/e LHR (p = 0.04), duration of mechanical ventilation (p = 0.02), duration of hospitalization (p < 0.001), pulmonary vasodilator use (p = 0.006), ECMO use (p = 0.03), tube feeding at discharge (p = 0.01), and respiratory support at discharge (p = 0.001) differed significantly between the two groups. In contrast, no significant differences were seen between the groups for best preductal arterial partial pressure of oxygen within 24 h, duration of oxygen use, duration of nitric oxide use, ECMO use, small for gestational age status, sex, prenatal diagnosis, polyhydramnios, prenatal steroid administration, extramural birth, cesarean delivery, and multiple gestation (Table 1).

For the multivariate analysis, variables were selected in accordance with findings from previous research and the results of our univariate analysis, specifically focusing on o/e LHR, ECMO use, and tube feeding. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, o/e LHR remained a predictor of NDI (adjusted odds ratio: 0.62; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.40–0.96; p = 0.03). ECMO use and tube feeding at discharge, although not statistically significant, indicated a trend toward an association with neurodevelopmental outcomes (adjusted odds ratio (OR) for ECMO use: 4.17, 95% CI: 0.33–52.43; p = 0.27 and adjusted OR for tube feeding at discharge: 3.74, 95% CI: 0.28–49.26; p = 0.32) (Table 2).

The o/e LHR was weakly correlated with the DQ score (DQ = 0.20 × o/e LHR + 84.6 ; R2 = 0.05; p = 0.04) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In this multicenter study, we used the extensive JCDHSG database to examine neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with isolated CDH at 3 years of age. The strengths of this study are the unprecedented number of included patients, and the use of a rigorous multivariate analysis methodology. Because CDH is associated with a variety of genetic disorders and comorbidities, limiting the database to cases without comorbidities or minor malformations allowed us to determine neurodevelopmental outcomes in isolated CDH. Our analysis of 132 cases confirmed that 75% of the infants achieved a DQ score ≥ 85. This confirms the efficacy of our treatment for CDH, a serious neonatal condition that often requires intensive and surgical intervention in the neonatal period. Notably, despite the complexities associated with the management of CDH, a significant proportion of children with isolated CDH were able to achieve developmental milestones with minimal neurological sequelae, underscoring the effectiveness of current treatments in saving lives while preserving quality of life. However, approximately 17% of the children had borderline development and developmental delays, with DQ scores < 85, similar to results in previous studies that examined several factors that predict developmental delays.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 In this study, we identified factors associated with the need for developmental support and demonstrated that 17% of cases with isolated CDH required such support, underscoring its prevalence in a substantial cohort.

In the multivariate analysis, we highlighted the importance of o/e LHR as an independent predictor of neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with CDH at 3 years of age. We also identified ECMO use and tube feeding at discharge as future research questions because of their potential impact on developmental outcomes.

In the present study, o/e LHR emerged as a significant predictor of developmental outcomes, with an adjusted OR of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.91–0.99; p = 0.03), underscoring its utility in early risk stratification.

In the past 10 years, numerous studies have highlighted the long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes in survivors of CDH,10,11,42 indicating a significant risk for neurodevelopmental impairment in these individuals.11,42,43 Various risk factors contribute to adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in CDH survivors. These include pulmonary hypoplasia, intrathoracic liver position, requirement for ECMO, right-sided CDH, patch repair, extended oxygen supplementation, and the need for invasive ventilation, among others.41,42,44,45 In children with isolated CDH, herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity during crucial stages of pulmonary development leads to pulmonary hypoplasia. The herniated organs not only compress the ipsilateral lung but also cause mediastinal shift, which can exert additional pressure on the contralateral lung. In severe cases, this bilateral pulmonary hypoplasia becomes life-threatening. To predict the severity of pulmonary hypoplasia prenatally and, consequently, postnatal survival, clinicians use imaging techniques that provide indirect measurements of fetal lung volume. Two widely recognized predictors of postnatal survival are the LHR and the o/e LHR, both of which are used globally.36,46 While several studies have linked a low LHR43,44,47 or intrathoracic liver position16,41 with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, other research has not found a significant association between these factors and neurodevelopmental outcomes.11,23,43 In our study, we found that o/e LHR, which is an indicator of lung hypoplasia, was a predicter of neurodevelopmental outcomes at 3 years of age in isolated CDH. This aligns with the physiological implications of reduced pulmonary function impacting overall developmental milestones. Furthermore, the o/e LHR correlated with the DQ score.

In this study, we showed that a low o/e LHR not only predicts mortality, but also has a significant impact on neurological outcomes. A low o/e LHR indicates fetal lung hypoplasia requiring prolonged postnatal interventions, such as mechanical ventilation and sedation. These intensive treatments, especially when prolonged, are associated with complex effects on neurodevelopment. Consequently, a low o/e LHR should be considered a predictor of adverse neurological and developmental outcomes, suggesting the need for a comprehensive approach to the management and follow-up of affected neonates.

A comparison of our findings with the existing literature highlights unique insights into the predictors of developmental outcomes in CDH survivors. Our rigorous multivariate analysis, which incorporated a broader set of variables compared with previous studies, provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing neurodevelopmental outcomes in this population.

Although ECMO use and tube feeding at discharge did not achieve statistical significance when comparing the two patient groups, there was a trend towards an association with poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes. From infancy through school age, normal cognition scores have been reported in CDH survivors, with normal to mildly delayed overall cognitive and language-development scores at preschool age.16,19,20,21,41,48,49 ECMO use is an independent predictor of impaired mental development.21,41,43 Our findings were similar and indicate the critical impact of pulmonary hypoplasia and other prenatal factors on long-term outcomes. Notably, our study reinforces the role of ECMO and tube feeding at discharge, which, while not reaching statistical significance, showed trends toward an association with poorer outcomes. These results suggest potential areas for improving clinical protocols and intervention strategies.

Tube feeding was significantly more common in patients who did not vs did undergo developmental evaluation, as shown in Table 1. The reasons for the need for tube feeding are unknown and may include developmental delay, which makes developmental testing difficult, and a genetic disorder (non-isolated CDH) that has not been definitively diagnosed. Further research is needed to clarify the factors that lead to the need for tube feeding in cases of isolated CDH.

Study limitations

While this study provides important insights into the neurodevelopmental outcomes of children with isolated CDH, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, 132 patients underwent developmental assessment among infants with isolated CDH, and 64 did not. However, the excluded group was not simply a skewed group. Prior to the analysis, we compared variables between the study patients (n = 132) and the excluded 64 patients who had not undergone developmental assessment. Only tube feeding at discharge was significantly higher in the excluded vs included patients (p = 0.007); other variables did not differ between the two groups (Supplemental Table). Second, we assessed the patients in this study using the KSPD, a developmental assessment widely used in Japan, which may complicate international comparisons. However, the KSPD has been validated and correlates highly with Bayley-III developmental test scores. The KSPD is widely used in the developmental assessment of preterm infants in Japan.39,50; therefore, the results of this study can be generalized internationally.

Conclusions

Our study, with its robust methodology and high number of included patients, identified o/e LHR as a significant predictor of neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with isolated CDH. The implications of ECMO use and tube feeding at discharge regarding long-term development warrant further exploration. Our findings provide valuable insights into ongoing efforts aimed at enhancing the quality of life and outcomes for CDH patients.

Data availability

The data underpinning the findings of this research are available from the corresponding author, K Toyoshima on reasonable request.

References

Tovar, J. A. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 7, 1 (2012).

Harting, M. T. & Lally, K. P. The congenital diaphragmatic hernia study group registry update. Semin Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 19, 370–375 (2014).

Long, A. M., Bunch, K. J., Knight, M., Kurinczuk, J. J. & Losty, P. D. Early population-based outcomes of infants born with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal. Neonatal. Ed. 103, F517–f522 (2018).

Lusk, L. A., Wai, K. C., Moon-Grady, A. J., Steurer, M. A. & Keller, R. L. Persistence of pulmonary hypertension by echocardiography predicts short-term outcomes in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J. Pediatr. 166, 251–256.e251 (2015).

Harting, M. T. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia-associated pulmonary hypertension. Semin Pediatr. Surg. 26, 147–153 (2017).

Kinsella, J. P., Ivy, D. D. & Abman, S. H. Pulmonary vasodilator therapy in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: acute, late, and chronic pulmonary hypertension. Semin Perinatol. 29, 123–128 (2005).

Kipfmueller, F. et al. Early postnatal echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary blood flow in newborns with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J. Perinat. Med. 46, 735–743 (2018).

Okuyama, H. et al. The Japanese experience with prenatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia based on a multi-institutional review. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 27, 373–378 (2011).

Snoek, K. G. et al. Standardized postnatal management of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe: the Cdh euro consortium consensus - 2015 Update. Neonatology 110, 66–74 (2016).

Hollinger, L. E. & Buchmiller, T. L. Long term follow-up in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Perinatol. 44, 151171 (2020).

Antiel, R. M. et al. Growth trajectory and neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J. Pediatr. Surg. 52, 1944–1948 (2017).

Van der Veeken, L. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prenat. Diagn. 42, 318–329 (2022).

Friedman, S. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors followed in a multidisciplinary clinic at Ages 1 and 3. J. Pediatr. Surg. 43, 1035–1043 (2008).

Tracy, S., Estroff, J., Valim, C., Friedman, S. & Chen, C. Abnormal neuroimaging and neurodevelopmental findings in a cohort of antenatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors. J. Pediatr. Surg. 45, 958–965 (2010).

Benjamin, J. R. et al. Perinatal factors associated with poor neurocognitive outcome in early school age congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors. J. Pediatr. Surg. 48, 730–737 (2013).

Danzer, E. et al. Longitudinal neurodevelopmental and neuromotor outcome in congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients in the first 3 years of life. J. Perinatol. 33, 893–898 (2013).

Danzer, E. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at one year of age in congenital diaphragmatic hernia infants not treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Pediatr. Surg. 50, 898–903 (2015).

Danzer, E. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 5 years of age in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J. Pediatr. Surg. 52, 437–443 (2017).

Leeuwen, L., Walker, K., Halliday, R. & Fitzgerald, D. A. Neurodevelopmental outcome in congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors during the first three years. Early Hum. Dev. 90, 413–415 (2014).

Snoek, K. G. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in high-risk congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients: an appeal for international standardization. Neonatology 109, 14–21 (2016).

Wynn, J. et al. Developmental outcomes of children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a multicenter prospective study. J. Pediatr. Surg. 48, 1995–2004 (2013).

Danzer, E. et al. Rate and risk factors associated with autism spectrum disorder in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 2112–2121 (2018).

King, S. K. et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: observed/expected lung-to-head ratio as a predictor of long-term morbidity. J. Pediatr. Surg. 51, 699–702 (2016).

Khalil, A. et al. Brain abnormalities and neurodevelopmental delay in congenital heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 43, 14–24 (2014).

Rollins, C. K., Newburger, J. W. & Roberts, A. E. Genetic contribution to neurodevelopmental outcomes in congenital heart disease: are some patients predetermined to have developmental delay? Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 29, 529–533 (2017).

Carey, A. S. et al. Effect of copy number variants on outcomes for infants with single ventricle heart defects. Circ. Cardiovasc Genet. 6, 444–451 (2013).

Wynn, J., Yu, L. & Chung, W. K. Genetic causes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 19, 324–330 (2014).

Cordier, A. G., Russo, F. M., Deprest, J. & Benachi, A. Prenatal diagnosis, imaging, and prognosis in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Perinatol. 44, 51163 (2020).

Peduzzi, P. et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 49, 1373–1379 (1996).

Vittinghoff, E. & McCulloch, C. E. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and COX regression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 165, 710–718 (2007).

Nagata, K. et al. Risk factors for the recurrence of the congenital diaphragmatic hernia-report from the long-term follow-up study of Japanese CDH study group. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 25, 9–14 (2015).

Yagi, M. et al. Twenty-year trends in neonatal surgery based on a nationwide Japanese surveillance program. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 31, 955–962 (2015).

Kitano, Y. et al. Liver position in fetal congenital diaphragmatic hernia retains a prognostic value in the era of lung-protective strategy. J. Pediatr. Surg. 40, 1827–1832 (2005).

Kitano, Y. et al. Re-evaluation of stomach position as a simple prognostic factor in fetal left congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a multicenter survey in Japan. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 37, 277–282 (2011).

Senat, M. V. et al. Prognosis of isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia using lung-area-to-head-circumference ratio: variability across centers in a national perinatal network. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 51, 208–213 (2018).

Jani, J. et al. Observed to expected lung area to head circumference ratio in the prediction of survival in fetuses with isolated diaphragmatic hernia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 30, 67–71 (2007).

Jani, J. C., Peralta, C. F. & Nicolaides, K. H. Lung-to-head ratio: a need to unify the technique. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 39, 2–6 (2012).

Itabashi, K. et al. Atarashii Zaitaikikannbetsu Shusseiji Taikaku Hyoujunnchi No Dounyuu Nitsuite (Introduction of New Gestational Age‐Specific Standards for Birth Size). J. Jpn. Pediatr. 114, 1271–1293 (2010).

Ishii, N., Kono, Y., Yonemoto, N., Kusuda, S. & Fujimura, M. Outcomes of infants born at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics 132, 62–71 (2013).

Kono, Y. et al. Developmental assessment of VLBW infants at 18 months of age: a comparison study between Kspd and Bayley III. Brain Dev. 38, 377–385 (2016).

Danzer, E. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia prospectively enrolled in an interdisciplinary follow-up program. J. Pediatr. Surg. 45, 1759–1766 (2010).

Montalva, L. et al. Neurodevelopmental impairment in children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: not an uncommon complication for survivors. J. Pediatr. Surg. 55, 625–634 (2020).

Danzer, E. et al. Preschool neurological assessment in congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors: outcome and perinatal factors associated with neurodevelopmental impairment. Early Hum. Dev. 89, 393–400 (2013).

Cortes, R. A. et al. Survival of severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia has morbid consequences. J. Pediatr. Surg. 40, 36–45 (2005). discussion 45-36.

Danzer, E. & Hedrick, H. L. Neurodevelopmental and neurofunctional outcomes in children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Early Hum. Dev. 87, 625–632 (2011).

Dekoninck, P. et al. Results of fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion for congenital diaphragmatic hernia and the set up of the randomized controlled total trial. Early Hum. Dev. 87, 619–624 (2011).

Church, J. T. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in Cdh survivors: a single institution’s experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 53, 1087–1091 (2018).

Gischler, S. J. et al. Interdisciplinary structural follow-up of surgical newborns: a prospective evaluation. J. Pediatr. Surg. 44, 1382–1389 (2009).

Bevilacqua, F. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in congenital diaphragmatic hernia survivors: role of ventilatory time. J. Pediatr. Surg. 50, 394–398 (2015).

Nishida, T. et al. Impact of comprehensive quality improvement program on outcomes in very-low-birth-weight infants: a cluster-randomized controlled trial in Japan. Early Hum. Dev. 190, 105947 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the Japanese Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group, which consists of experts in neonatology, pediatric surgery, and related fields. All authors are members of this consortium and contributed to the collaborative research efforts. We extend our heartfelt gratitude to the Japanese Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group for their invaluable contributions. We thank Jane Charbonneau, DVM, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (Grant No. 20FC1017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

K Toyoshima and H Aoki made substantial contributions to the study conception and design, and performed the statistical analyses. All authors made substantial contributions to data collection and collectively interpreted the findings. The manuscript was initially drafted by K Toyoshima and H Aoki. All authors revised the article critically for important intellectual content, and all authors gave final approval of the version to be published version. All authors take full responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Consent statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all parents.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Toyoshima, K., Aoki, H., Katsumata, K. et al. Isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia and three-year neurodevelopmental outcomes. Pediatr Res 98, 690–696 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-03870-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-03870-z