Abstract

Purpose

Recent advancements in the management of biochemical recurrence (BCR) following local treatment for prostate cancer (PCa), including the use of androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs), have broadened the spectrum of therapeutic options. We aimed to compare salvage therapies in patients with BCR after definitive local treatment for clinically non-metastatic PCa with curative intent.

Methods

In October 2023, we queried PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective studies reporting data on the efficacy of salvage therapies in PCa patients with BCR after radical prostatectomy (RP) or radiation therapy (RT). The primary endpoint was metastatic-free survival (MFS), and secondary endpoints included progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results

We included 19 studies (n = 9117); six trials analyzed RT-based strategies following RP, ten trials analyzed hormone-based strategies following RP ± RT or RT alone, and three trials analyzed other agents. In a pairwise meta-analysis, adding hormone therapy to salvage RT significantly improved MFS (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.57–0.84, p < 0.001) compared to RT alone. Based on treatment ranking analysis, among RT-based strategies, the addition of elective nodal RT and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was found to be the most effective in terms of MFS. On the other hand, among hormone-based strategies, enzalutamide + ADT showed the greatest benefit for both MFS and OS.

Conclusions

The combination of prostate bed RT, elective pelvic irradiation, and ADT is the preferred treatment for eligible patients with post-RP BCR based on our analysis. In remaining patients, or in case of post-RT recurrence, especially for those with high-risk BCR, the combination of ADT and ARSI should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While local treatments such as radical prostatectomy (RP) or radiation therapy (RT) are effective in early-stage prostate cancer (PCa), 20–40% of patients experience biochemical recurrence (BCR) [1]. Approximately one-third of patients with BCR already have detectable metastasis on conventional imaging, which is still likely underestimated considering the results of studies analyzing prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography (PSMA-PET) in the BCR setting [2, 3]. Although the majority of patients with low-risk BCR are unlikely to develop metastases [4], high-risk BCR is associated with mortality [5,6,7,8], highlighting the compelling need to improve BCR management.

Current guidelines recommend RT with or without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for patients who experience BCR following RP [9,10,11]. In addition, ADT is recommended as an option for those experiencing BCR after receiving adjuvant, salvage, or definitive RT. The implementation of androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs) and other agents (e.g., docetaxel [DOC]) as an effective treatment for advanced PCa, may also potentially broaden therapeutic choices in BCR [12]. However, despite emerging data, there is a lack of comprehensive synthesis in the literature to guide clinical decision-making for BCR treatment. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review, meta-analysis, and network meta-analysis (NMA) to identify the most effective salvage therapy strategy for patients with BCR following definitive local therapy.

Methods

Our study protocol is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systemic Reviews database (PROSPERO: CRD42023481828). This meta-analysis adheres to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and AMSTAR2 checklist [13, 14].

Study selection and characteristics

On 27 October 2023, a systemic search was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective studies reporting data on the efficacy of salvage therapies in PCa patients with BCR after RP or RT. The detailed search strategy is shown in Supplementary Appendix 1. Two investigators independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility, followed by full-text reviews of relevant studies. Manual searches of reference lists of relevant articles were also carried out to find additional studies of interest. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with co-authors.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To formulate our clinical question, we applied the PICO framework [15]. Our study population included patients with PCa experiencing BCR after RP or RT without visible locoregional recurrence or distant metastasis (Patients). We focused on a wide range of therapeutic interventions aiming to improve oncologic outcomes, encompassing various treatment modalities for managing BCR (Interventions), comparing these interventions against the established standard of care (Comparison). The primary outcome of interest was distant metastasis-free survival (MFS). Secondary endpoints included progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) (Outcome). PFS includes either BCR or clinical progression, while MFS focuses solely on the absence of metastatic disease. Additionally, the definition of BCR and progression varied across the included studies. These definitions are detailed in Table 1. We excluded retrospective and single-arm studies, reviews, editorial comments, replies to authors, and non-English language articles. Studies involving non-medical compounds were also omitted. Additionally, we excluded studies comparing different radiation therapy techniques, such as dose and fraction schedule, to avoid potential confusion and ensure clearer comparisons across studies.

Data extraction

Two authors independently extracted details on study design, patient characteristics, inclusion criteria, definition of disease progression, oncologic outcomes, and adverse events (AEs). Subsequently, the results of the Kaplan–Meier analyses, hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from Cox regression models for PFS, MFS, and OS were retrieved. Studies providing HR data with detailed statistical measures were included in the meta-analysis and NMA. Studies lacking such detailed data were considered for the systematic review but excluded from the meta-analysis and NMA. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with co-authors.

Risk-of-bias assessment

Study quality and risk of bias were assessed using the Risk-of-Bias version 2 (ROB2) tool as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Supplementary Fig. 1) [16]. The presence of confounders was determined by consensus and a review of the literature. The Risk-of-Bias assessments of each study were conducted independently by two authors.

Statistical analyses

Standard pairwise meta-analysis

Quantitative data synthesis was carried out with the R statistical software 4.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For our calculations, we followed the methods recommended by the working group of the Cochrane Collaboration [17]. Based on the likely heterogeneity across studies, a random-effect model was used for calculations of HRs [18]. To assess and compare the MFS and OS of different treatments for BCR, we calculated pooled HRs with 95% CI using the “meta” package in R. We utilized forest plots to visualize event rates and effect measures. In our analysis, the statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. The minimum number of studies to perform a meta-analysis was two. We assessed heterogeneity using Cochran’s Q test and explored its causes when significant (p < 0.05) [19]. To evaluate the presence of publication bias, funnel plots were used (Supplementary Fig. 2). We performed Egger’s test if 10 or more studies were included in each analysis.

Network meta-analysis

A network meta-analysis (NMA) using random-effect models with a frequentist approach was carried out for direct and indirect treatment comparisons [20, 21]. In the assessment of oncological outcomes, contrast-based analyses were applied with estimated differences in the log HR and the standard error calculated from the published HR and 95% CIs [22]. When a three-arm trial reported only two comparisons, we calculated the additional comparison independently. The relative effects were presented as HRs and 95% CIs [21]. We also estimated the relative ranking of the different treatments for each outcome using the surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) [21]. Network plots were utilized to illustrate the connectivity of the treatment networks (Supplementary Fig. 3). All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), utilizing the “netmeta” package in R.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The search string is presented in Fig. 1. According to the application of our inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 19 RCTs [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], comprising 9117 PCa patients with BCR following definitive local treatments, were selected. The patient characteristics and their outcomes are detailed in Tables 1 and 2. Eighteen studies included patients who had undergone RP [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, 41]. Of these, 11 studies [25,26,27,28, 30,31,32,33, 35, 36, 38] allowed the use of adjuvant or salvage RT after RP. Seven studies [26, 31,32,33, 38,39,40] included RT as the primary treatment. In the context of RT-based strategies, most studies investigated the effectiveness of combining RT with hormone therapy: two on ARSIs [29, 34], two on bicalutamide (BIC) [24, 41], and two on ADT [37, 42], with one study [37] also examining elective pelvic node irradiation. In terms of hormone-based therapies, five studies [26, 28, 31, 33, 36] used the addition of ARSIs, and two studies [30, 35] combined DOC with ADT as a primary intervention. Three studies [38,39,40] investigated the timing and duration of ADT. The other three studies used dutasteride, sipuleucel-T, or exisulind. The definition of BCR and progression varied among studies. The PROTECT trial [27] defined BCR as an increase in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) without a specific threshold, whereas others set different PSA level criteria (for post-RP: PSA levels above 0.05–1.0 ng/ml; for post-RT: PSA levels above 1.0–2.0 ng/ml or above nadir + 2.0 ng/ml). Notably, none of the studies utilized PSMA-PET for metastasis detection; all used conventional imaging modalities such as CT, bone scan, and MRI. The median follow-up period ranged from 30 to 112 months.

Due to the heterogeneity among the definitions of PFS, we conducted only a qualitative synthesis of the data. Therefore, studies providing only PFS data were excluded from our analyses. Additionally, among the studies reviewed, two trials [24, 34] exhibited unique designs that led to their exclusion from our NMA. In the JCOG0401 trial [24], which compared BIC with RT, approximately half of the patients in the RT arm received BIC after randomization. Similarly, the FORMULA 509 trial [34] allowed pelvic lymph node radiation therapy (PLNRT) for patients with pN1 and offered it as an option for those with pN0. These unique design elements made it challenging to integrate their results into the NMA framework.

Risk-of-bias assessment

The results of bias evaluation for each domain across the included studies are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Most RCTs exhibited a low risk of bias across the majority of domains. However, some concerns were identified in certain areas for a few studies. Funnel plots of each analysis are depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2.

RT-based treatment strategies for patients with BCR after RP

A total of six RCTs, comprising 3859 participants, evaluated RT-based treatments for patients with BCR after RP [23, 24, 29, 34, 37, 41]. These studies administered single-agent or combined hormone therapy (HT), such as enzalutamide (ENZ), abiraterone (ABI), apalutamide (APA), bicalutamide (BIC), and ADT administered between 6 weeks to 2 years in combination with RT. Detailed descriptions of the studies can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

The SALV-ENZ trial [29] showed that adding ENZ to RT improved freedom from PSA progression (HR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.19–0.92, p = 0.031), especially for high-risk patients, such as pT3 (HR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.07–0.69) and surgical margin-positive (HR: 0.14, 95% CI: 0.03–0.64). The JCOG0401 trial [24] demonstrated RT with/without BIC prolonged PFS compared to BIC alone (HR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.38–0.82, p = 0.001). The FORMULA 509 trial [34] compared ABI + APA with BIC, both added to ADT and RT. No significant difference was noted overall; however, a subgroup analysis with PSA > 0.5 ng/ml revealed a significant improvement in both PFS (HR: 0.50, 90% CI: 0.30–0.86) with ABI + APA. The NRG Oncology/RTOG 0534 SPPORT trial [37] demonstrated the benefits of adding PLNRT to RT and ADT in freedom from progression (HR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.63–1.07, p = 0.048). However, this was accompanied by an increase in the incidence of acute AEs Grade 2+ (RT + ADT: 37.7%, PLNRT + RT + ADT: 44.6%).

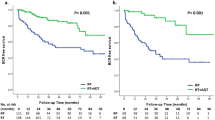

Standard pairwise meta-analysis (HT + RT vs. RT alone)

In our pairwise meta-analyses, we were able to summarize data from three articles [23, 37, 41]. Combining HT with RT was found to significantly improve MFS compared to RT alone (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.57–0.84, p < 0.001). There was some evidence for improved OS, which did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (HR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.68–1.00, p = 0.05) (Fig. 2). Cochran’s Q test revealed no significant heterogeneity among the included studies.

A MFS for HT + RT vs. RT: this panel shows the meta-analysis results for MFS comparing HT combined with RT versus RT alone. B OS for HT + RT vs. RT: this panel illustrates OS outcomes for HT + RT compared to RT alone. C OS for DOC + ADT vs. ADT: this panel demonstrates OS comparing DOC combined with ADT versus ADT alone. Symbols represent HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the diamonds indicate pooled estimates. OS overall survival, RT radiotherapy, HT hormone therapy, MFS metastasis-free survival, DOC docetaxel, CI confidence interval, ADT androgen deprivation therapy, HR hazard ratio.

Network meta-analysis (NMA)

Our NMAs included three RCTs with four RT-based treatments [23, 37, 41]. The RT-based NMA focused on the addition of HT or PLNRT to RT. All combinations, including ADT + RT (HR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.58–0.93), BIC + RT (HR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.46–0.87), and PLNRT + ADT + RT (HR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.35–0.78), significantly improved MFS compared to RT alone as shown in Fig. 3. However, compared to RT + ADT, no treatment combination demonstrated significant improvement in MFS (Supplementary Fig. 4). Based on SUCRA analysis, the combination of RT + ADT + PLNRT (90%) had the highest likelihood of providing the maximal MFS benefit, followed by BIC + RT (68%) and RT + ADT (42%). In terms of OS, no treatment combination showed significant improvement (Fig. 4). According to SUCRA analysis for OS, BIC + RT (86%) ranked highest for OS benefit. No significant heterogeneity was observed in each analysis.

A RT-based treatment: A1 Forest plots, A2 Treatment ranking based on SUCRA graph, B Hormone-based treatment: B1 Forest plots, B2 Treatment ranking based on SUCRA graph. PRISMA preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, MFS metastatic-free survival, HT hormone therapy, RT radiation therapy, OS overall survival, DOC docetaxel, ADT androgen deprivation therapy, NMA network meta-analysis, BCR biochemical recurrence, SUCRA surface under the cumulative ranking.

Hormone-based treatment strategies for patients with BCR after RP or RT

Androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs)

Five RCTs comprising 1979 participants assessed the impact of ARSIs administered for 8–12 months, on oncological outcomes in patients with BCR after definitive local treatment [26, 28, 31, 33, 36].

The EMBARK trial [31] showed that ENZ + ADT improved both PFS (HR: 0.07, 95% CI: 0.03–0.14, p < 0.001) and MFS (HR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.30–0.61, p < 0.001). APA + ADT improved PSA-PFS in the PRESTO trial (HR: 0.52, 95% CI: 0.35–0.77), but not in the NCT01790126 trial (0.56, 95% CI: 0.23–1.36, p = 0.196) (Supplementary Table 2). The combination of ABI and ADT demonstrated effectiveness in reducing disease progression in the NCT01786265 trial [33] (HR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.47–0.87, p = 0.004); however, no significant difference in median PSA-PFS was found in the NCT01751451 study [28] (ABI + ADT: 64.4 weeks, 95% CI: 57.9–NA; ADT: 54.9 weeks, 95% CI: 47.9–60.7 weeks). Furthermore, the combination of ABI, APA, and ADT showed improvements in PFS compared to ADT alone in the PRESTO trial [36] (HR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.32–0.71). The AE profiles are similar to those observed in previous RCTs for each respective drug [43,44,45,46].

Docetaxel (DOC)

Two RCTs comprising 663 participants assessed the impact of docetaxel (DOC) on oncological outcomes in patients with BCR post-RP [30, 35]. The duration of treatment varied among studies, with DOC ranging from 6 to 10 cycles and ADT from 12 to 18 months. DOC use was not significantly associated with PFS due to the wide range of CIs in two studies. In addition, DOC use was associated with a higher incidence of neutropenia, alopecia, and fatigue, among others.

Standard pairwise meta-analysis (DOC + ADT vs. ADT alone)

Adding DOC to ADT did not significantly improve OS compared to ADT alone (HR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.46–1.18, p = 0.2) (Fig. 2). As the NCT00764166 trial [35] was the only study to evaluate MFS, a meta-analysis for MFS was not performed. Cochran’s Q test revealed no significant heterogeneity among the studies included.

Timing and duration of ADT

The NCIC trial [40] conducted a comparison between intermittent ADT (n = 690) to continuous ADT (n = 696). Intermittent ADT was associated with significantly improved outcomes for hot flashes (p < 0.001), desire for sexual activity (p < 0.001), and urinary symptoms (p < 0.01), while no significant difference was shown in OS. In the NCT00928434 trial [39], which randomized patients experiencing BCR to either intermittent ADT (n = 175) or continuous ADT (n = 228), the sexual drive was significantly improved in patients undergoing intermittent ADT compared to those receiving continuous ADT (p = 0.027).

The TOAD trial [38] assessed the implication of initiating ADT on a delayed basis (n = 137) compared to immediate initiation of ADT (n = 124). There was no significant difference in OS (HR: 0.59, 95% CI: 0.26–1.30, p = 0.19). Regarding QoL between the two arms, arm-specific rates of change over time did not statistically differ (pinteraction = 0.14).

Network meta-analysis of hormone-based treatments

As shown in Fig. 3, ENZ + ADT (HR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.29–0.60) and ENZ alone (HR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.46–0.87) significantly improved MFS compared to ADT alone. SUCRA analysis ranked ENZ + ADT (99%) as the most effective for MFS, followed by ENZ alone (67%). In terms of OS, no agents significantly improved MFS compared to ADT alone (Fig. 4). Based on the SUCRA analysis, ENZ + ADT (83%) had the highest likelihood of providing the maximal benefit for OS. Cochran’s Q test revealed no significant heterogeneity in each analysis.

Other treatments

Three RCTs, comprising 566 patients, assessed the impact of other agents on oncological outcomes in patients with BCR. All of these studies used a placebo as a comparator; therefore, we did not include them in our NMAs. Dutasteride significantly reduced disease progression (risk ratio [RR]): 0.41, 95% CI: 0.25–0.67, p < 0.001 in the ARTS trial [32], while no significant difference in PFS and MFS were noted with sipuleucel-T in the PROTECT trial [27]. Goluboff et al. [25] demonstrated that exisulind showed potential benefits in high-risk patients. Detailed outcomes and AEs are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Discussion

This systematic review, pairwise meta-analysis, and NMA represent the comprehensive assessment of various interventions on oncological outcomes in PCa patients who experienced BCR following definitive local treatment. Our study highlights several key findings. First, the addition of HT to RT improved MFS compared to RT alone in patients with BCR after RP. Furthermore, our treatment ranking analysis identified PLNRT in combination with ADT and RT to exhibit the highest benefit in terms of MFS. Second, there is evidence suggesting that ARSI-based treatments might improve PFS in patients with BCR following RP or RT compared to ADT alone. Conversely, the impact of DOC on PFS, MFS, and OS appears to be less clear. In addition, ENZ + ADT was shown to be the most effective in enhancing both MFS and OS among hormone-based treatment strategies. Third, although no significant differences were found in PFS and MFS among the overall patient cohort, the addition of ARSI to RT was associated with improvement in PFS and MFS, especially in patients with adverse prognostic factors, such as pT3 staging, positive surgical margins, and elevated PSA levels.

Our meta-analysis indicated that adding HT to RT potentially reduced the risk of metastasis by 31% in PCa patients with BCR after RP, with a suggested but not statistically significant 17% improvement in OS. Our SUCRA analysis revealed PLNRT + ADT + RT as the most effective combination for improving MFS. However, the addition of PLNRT did not demonstrate a statistically significant superiority over ADT + RT in our NMA model either in terms of MFS and OS. Although it is crucial to weigh the benefit against potential AEs, the NRG Oncology/RTOG 0534 SPPORT trial [37] revealed that the addition of PLNRT resulted in increased rates of acute AEs. Interestingly, the addition of BIC to RT was also found to carry great potential in improving MFS and OS compared to RT alone, though the improvement in OS did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance. Although BIC is not recommended for many indications, considering its acceptable AE profile and our results it could potentially be a promising combination partner with RT in BCR after RP; especially those with less aggressive PCa and longer PSA doubling time. It should be noted that the observed benefits of PLNRT and BIC in our analyses were based solely on data from a single study for each: the NRG Oncology/RTOG 0534 SPPORT [37] and the RTOG 9601 trial [47], respectively. This limited data source might lead to over- or under-interpretation. Therefore, more prospective data is needed to further assess the potential benefits of adding PLNRT or BIC to RT.

We found that combining ARSI with ADT reduced the risk of disease progression in the majority of studies, while DOC + ADT did not significantly impact PFS or OS. Our treatment rankings indicated that ENZ + ADT was the most likely to improve MFS compared to ADT alone among hormone-based treatments. Determination of when and for how long ADT should be initiated in the salvage setting remains unclear. For instance, no studies have indicated that immediate ADT significantly improves OS [38, 48]. Furthermore, long-term ADT can lead to various AEs (e.g., cardiovascular events, osteoporosis, cognitive impairment) [49,50,51]. Additionally, EAU low-risk BCR significantly correlates with more favorable mortality outcomes than high-risk [52]. Therefore, immediate ADT is not recommended for patients with low-risk BCR by guidelines [53]. Considering these findings, alternative treatments that improve mortality within tolerable AEs are desirable for patients with BCR after RT. In the EMBARK trial [31], ENZ + ADT improved in MFS, a strong surrogate for OS in men receiving RT [54], compared to ADT alone. Importantly, this improvement came with a similar frequency of AEs as seen with ADT alone, suggesting that ENZ + ADT could be an effective and safe strategy for patients with BCR following RT. On the other hand, while RT-based treatment is currently the standard therapy for BCR patients after RP [53], the efficacy of hormone-based treatment for these patients remains unclear. In this study, direct comparisons between ADT- and RT-based strategies were not feasible due to the diversity of primary treatments (e.g., RP, RP + adjuvant/salvage RT, RT). Although interpretations should be made with caution due to the short follow-up period and small sample size, the JCOG0401 trial, which compared BIC alone to RT with/without BIC, showed no significant difference in MFS and OS. While RT remains a standard option, ARSIs + ADT may have the potential to become a prime option comparable to RT with/without ADT. However, these discussions have not taken into account the presence of undetectable metastasis by conventional imaging. Recently, PSMA-PET has shown promising effectiveness in detecting metastasis missed by conventional imaging, such as pelvic lymph node metastases (42%) and bone metastases (15%) [55, 56]. Although metastatic-directed therapies (MDT) targeting oligometastases have gained attention, it remains an experimental approach [57]. Therefore, with the future integration of PSMA-PET, treatment decisions are expected to shift from relying on risk stratification or primary treatment to PSMA-PET findings. RCTs comparing PSMA-PET-based MDT and ARSI + RT are eagerly awaited.

Based on our systematic review, the benefit of adding ARSIs to RT was observed, especially for PCa patients with prognostically adverse factors. The SALV-ENZA trial [29] demonstrated that ENZ + RT decreased disease progression compared to RT alone by 58%, particularly in high-risk patients, such as pT3 (78%) and margin-positive (86%). Furthermore, the FORMULA trial [34] also found a significant reduction in disease progression (50%) and metastasis (68%) with the addition of ABI and APA to ADT + RT in patients with PSA > 0.5 ng/ml. In contrast, other studies investigating the effect of ADT [23, 37] and BIC [41] did not demonstrate such a differential benefit in similar settings. Therefore, combining ARSIs with RT could become a key approach in the treatment, especially for PCa patients with these prognostically adverse factors, such as high PSA, pT3, and margin-positive. The results of ongoing studies on ARSIs, such as the BALANCE trial (APA + RT vs. placebo + RT alone) and the STEEL trial [58] (ENZ + ADT + RT vs. ADT + RT) are anticipated to further validate the ARSI + RT combination in the BCR setting.

Our study has several limitations. First, there were notable variations in patient baseline characteristics across the included studies. Additionally, the difference among definitions of BCR and disease progression across studies could lead to heterogeneity in the results and their interpretation. Therefore, due to these inconsistencies, especially regarding the crucial aspect of disease progression in clinical practice, we refrained from conducting a meta-analysis and NMA for this outcome. Furthermore, due to the heterogeneity and the lack of subgroup analysis in the included studies, we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses stratified by patient characteristics. This limitation means we could not determine the optimal treatment for each patient. Second, the duration of follow-up and medication use varied among studies, potentially impacting the assessment of oncological outcomes. Third, the included studies exhibited a diversity of initial treatments, including RP, RT, and RP plus adjuvant/salvage RT. Furthermore, the proportion of patients undergoing these treatments varied among the studies. This mixture of treatment scenarios hindered our ability to conduct distinct analyses for each specific context of salvage therapy following different local treatments. Fourth, the assessment of metastasis in the included studies was based on conventional imaging, and PSMA-PET was not utilized. This raises the possibility of inappropriate treatment for patients with micrometastases due to less sensitive imaging. Fifth, due to the variability in the reporting styles of AEs across the included studies, we were limited to performing meta-analyses or NMAs of AEs. Sixth, the STAMPEDE trial (arm A, J) [59] also investigated patients with BCR and locally advanced PCa; however, separate data for these groups could not be obtained. Thus, we did not include the STAMPEDE trial [59] in our study. Finally, our findings may not fully apply to patients with low-risk BCR, particularly those with a life expectancy of less than 10 years or those unwilling to undergo salvage therapy. For those patients, active follow-up could be a more appropriate management strategy [4].

Conclusion

We found that combining HT with RT effectively prevents disease progression and metastasis in PCa patients who experienced BCR following definitive local treatment. Furthermore, adding PLNRT to this combination improved MFS. ARSIs improved oncological outcomes when combined with RT or ADT. Further, well-designed RCTs are awaited to clarify the comparative oncologic outcomes of RT-based and hormone-based treatments in different clinical scenarios, with a particular focus on the role of ARSIs.

References

le Guevelou J, Achard V, Mainta I, Zaidi H, Garibotto V, Latorzeff I, et al. PET/CT-based salvage radiotherapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: impact on treatment management and future directions. Front Oncol. 2021;11:742093.

Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenberger MA, Chan DW, Pearson JD, Walsh PC. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 1999;281:1591–7.

Roehl KA, Han M, Ramos CG, Antenor JA, Catalona WJ. Cancer progression and survival rates following anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy in 3,478 consecutive patients: long-term results. J Urol. 2004;172:910–4.

Tilki D, Preisser F, Graefen M, Huland H, Pompe RS. External validation of the European Association of Urology Biochemical Recurrence Risk Groups to Predict Metastasis and Mortality After Radical Prostatectomy in a European Cohort. Eur Urol. 2019;75:896–900.

Jackson WC, Suresh K, Tumati V, Allen SG, Dess RT, Salami SS, et al. Intermediate endpoints after postprostatectomy radiotherapy: 5-year distant metastasis to predict overall survival. Eur Urol. 2018;74:413–9.

Royce TJ, Chen MH, Wu J, Loffredo M, Renshaw AA, Kantoff PW, et al. Surrogate end points for all-cause mortality in men with localized unfavorable-risk prostate cancer treated with radiation therapy vs radiation therapy plus androgen deprivation therapy: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:652–8.

Freiberger C, Berneking V, Vögeli TA, Kirschner-Hermanns R, Eble MJ, Pinkawa M. Long-term prognostic significance of rising PSA levels following radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer - focus on overall survival. Radiat Oncol. 2017;12:98.

Choueiri TK, Chen MH, D’Amico AV, Sun L, Nguyen PL, Hayes JH, et al. Impact of postoperative prostate-specific antigen disease recurrence and the use of salvage therapy on the risk of death. Cancer. 2010;116:1887–92.

Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II-2020 update: treatment of relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2021;79:263–82.

Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra N, An Y, Barocas D, Bitting R, et al. Prostate cancer, version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:1067–96. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.0050.

Morgan TM, Boorjian SA, Buyyounouski MK, Chapin BF, Chen DYT, Cheng HH, et al. Salvage therapy for prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline part ii: treatment delivery for non-metastatic biochemical recurrence after primary radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2024;211:518–25.

Rajwa P, Pradere B, Gandaglia G, van den Bergh RCN, Tsaur I, Shim SR, et al. Intensification of systemic therapy in addition to definitive local treatment in nonmetastatic unfavourable prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 2022;82:82–96.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Health. 2015;13:147–53.

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:Ed000142.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

van Valkenhoef G, Lu G, de Brock B, Hillege H, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Automating network meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:285–99.

Shim SR, Kim SJ, Lee J, Rücker G. Network meta-analysis: application and practice using R software. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019013.

Woods BS, Hawkins N, Scott DA. Network meta-analysis on the log-hazard scale, combining count and hazard ratio statistics accounting for multi-arm trials: a tutorial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:54.

Carrie C, Magné N, Burban-Provost P, Sargos P, Latorzeff I, Lagrange JL, et al. Short-term androgen deprivation therapy combined with radiotherapy as salvage treatment after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 16): a 112-month follow-up of a phase 3, randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1740–9.

Yokomizo A, Wakabayashi M, Satoh T, Hashine K, Inoue T, Fujimoto K, et al. Salvage radiotherapy versus hormone therapy for prostate-specific antigen failure after radical prostatectomy: a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial (JCOG0401)†[Formula presented]. Eur Urol. 2020;77:689–98.

Goluboff ET, Prager D, Rukstalis D, Giantonio B, Madorsky M, Barken I, et al. Safety and efficacy of exisulind for treatment of recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2001;166:882–6.

Aggarwal R, Alumkal JJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Higano CS, Bryce AH, Lopez-Gitlitz A, et al. Randomized, open-label phase 2 study of apalutamide plus androgen deprivation therapy versus apalutamide monotherapy versus androgen deprivation monotherapy in patients with biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer. 2022;2022:5454727.

Beer TM, Bernstein GT, Corman JM, Glode LM, Hall SJ, Poll WL, et al. Randomized trial of autologous cellular immunotherapy with sipuleucel-T in androgen-dependent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4558–67.

Autio KA, Antonarakis ES, Mayer TM, Shevrin DH, Stein MN, Vaishampayan UN, et al. Randomized phase 2 trial of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone, degarelix, or the combination in men with biochemically recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2021;34:70–78.

Tran PT, Lowe K, Tsai HL, Song DY, Hung AY, Hearn JWD, et al. Phase II randomized study of salvage radiation therapy plus enzalutamide or placebo for high-risk prostate-specific antigen recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: the SALV-ENZA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1307–17.

Morris MJ, Mota JM, Lacuna K, Hilden P, Gleave M, Carducci MA, et al. Phase 3 randomized controlled trial of androgen deprivation therapy with or without docetaxel in high-risk biochemically recurrent prostate cancer after surgery (TAX3503). Eur Urol Oncol. 2021;4:543–52.

Freedland SJ, de Almeida Luz M, De Giorgi U, Gleave M, Gotto GT, Pieczonka CM, et al. Improved outcomes with enzalutamide in biochemically recurrent prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1453–65.

Schröder F, Bangma C, Angulo JC, Alcaraz A, Colombel M, McNicholas T, et al. Dutasteride treatment over 2 years delays prostate-specific antigen progression in patients with biochemical failure after radical therapy for prostate cancer: results from the randomised, placebo-controlled avodart after radical therapy for prostate cancer study (ARTS). Eur Urol. 2013;63:779–87.

Spetsieris N, Boukovala M, Alafis I, Davis J, Zurita A, Wang X, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in non-metastatic biochemically recurrent castration-naïve prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2021;157:259–67.

Nguyen PL, Kollmeier M, Rathkopf DE, Hoffman KE, Zurita AJ, Spratt DE, et al. FORMULA-509: a multicenter randomized trial of post-operative salvage radiotherapy (SRT) and 6 months of GnRH agonist with or without abiraterone acetate/prednisone (AAP) and apalutamide (Apa) post-radical prostatectomy (RP). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:303.

Oudard S, Latorzeff I, Caty A, Miglianico L, Sevin E, Hardy-Bessard AC, et al. Effect of adding docetaxel to androgen-deprivation therapy in patients with high-risk prostate cancer with rising prostate-specific antigen levels after primary local therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:623–32.

Aggarwal RR, Heller G, Hillman DW, Xiao H, Picus J, Taplin M-E, et al. Baseline characteristics associated with PSA progression-free survival in patients (pts) with high-risk biochemically relapsed prostate cancer: results from the phase 3 PRESTO study (AFT-19). J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:208–208.

Pollack A, Karrison TG, Balogh AG, Gomella LG, Low DA, Bruner DW, et al. The addition of androgen deprivation therapy and pelvic lymph node treatment to prostate bed salvage radiotherapy (NRG Oncology/RTOG 0534 SPPORT): an international, multicentre, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1886–901.

Duchesne GM, Woo HH, Bassett JK, Bowe SJ, D’Este C, Frydenberg M, et al. Timing of androgen-deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer with a rising PSA (TROG 03.06 and VCOG PR 01-03 [TOAD]): a randomised, multicentre, non-blinded, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:727–37.

Crawford ED, Shore N, Higano CS, Neijber A, Yankov V. Intermittent androgen deprivation with the gnrh antagonist degarelix in men with biochemical relapse of prostate cancer. Am J Hematol Oncol. 2015;11:6–13.

Crook JM, O’Callaghan CJ, Duncan G, Dearnaley DP, Higano CS, Horwitz EM, et al. Intermittent androgen suppression for rising PSA level after radiotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:895–903.

Shipley WU, Seiferheld W, Lukka HR, Major PP, Heney NM, Grignon DJ, et al. Radiation with or without Antiandrogen Therapy in Recurrent Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:417–28.

Carrie C, Hasbini A, de Laroche G, Richaud P, Guerif S, Latorzeff I, et al. Salvage radiotherapy with or without short-term hormone therapy for rising prostate-specific antigen concentration after radical prostatectomy (GETUG-AFU 16): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:747–56.

Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Bjartell A, Chung BH, Pereira de Santana Gomes AJ, Given R, et al. Apalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: final survival analysis of the randomized, double-blind, phase III TITAN study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2294–303.

James ND, Clarke NW, Cook A, Ali A, Hoyle AP, Attard G, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisolone for metastatic patients starting hormone therapy: 5-year follow-up results from the STAMPEDE randomised trial (NCT00268476). Int J Cancer. 2022;151:422–34.

Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:686–700.

Sweeney CJ, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, Begbie S, Cheung L, Chi KN, et al. Testosterone suppression plus enzalutamide versus testosterone suppression plus standard antiandrogen therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (ENZAMET): an international, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:323–34.

Jackson WC, Tang M, Schipper MJ, Sandler HM, Zumsteg ZS, Efstathiou JA, et al. Biochemical failure is not a surrogate end point for overall survival in recurrent prostate cancer: analysis of NRG oncology/RTOG 9601. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:3172–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.02741.

Siddiqui SA, Boorjian SA, Inman B, Bagniewski S, Bergstralh EJ, Blute ML. Timing of androgen deprivation therapy and its impact on survival after radical prostatectomy: a matched cohort study. J Urol. 2008;179:1830–7.

Rosenberg MT. Cardiovascular risk with androgen deprivation therapy. Int J Clin Pr. 2020;74:e13449.

Daniell HW. Osteoporosis due to androgen deprivation therapy in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2001;58:101–7.

Mundell NL, Daly RM, Macpherson H, Fraser SF. Cognitive decline in prostate cancer patients undergoing ADT: a potential role for exercise training. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24:R145–55.

Preisser F, Abrams-Pompe RS, Stelwagen PJ, Böhmer D, Zattoni F, Magli A, et al. European Association of Urology Biochemical Recurrence risk classification as a decision tool for salvage radiotherapy-a multicenter study. Eur Urol. 2024;85:164–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.05.038.

Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II—2020 Update: treatment of relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2021;79:263–82.

Jackson WC, Tang M, Schipper MJ, Sandler HM, Zumsteg ZS, Efstathiou JA, et al. Biochemical failure is not a surrogate end point for overall survival in recurrent prostate cancer: analysis of NRG Oncology/RTOG 9601. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:3172–9.

Watabe T, Uemura M, Soeda F, Naka S, Ujike T, Hatano K, et al. High detection rate in [(18)F]PSMA-1007 PET: interim results focusing on biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer patients. Ann Nucl Med. 2021;35:523–8.

Fendler WP, Calais J, Eiber M, Flavell RR, Mishoe A, Feng FY, et al. Assessment of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET accuracy in localizing recurrent prostate cancer: a prospective single-arm clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:856–63.

Miszczyk M, Rajwa P, Yanagisawa T, Nowicka Z, Shim SR, Laukhtina E, et al. The efficacy and safety of metastasis-directed therapy in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Urol. 2024;85:125–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.10.012.

Posadas EM, Gay HA, Pugh SL, Morgan TM, Yu JB, Lechpammer S, et al. RTOG 3506 (STEEL): a study of salvage radiotherapy with or without enzalutamide in recurrent prostate cancer following surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:TPS5601.

Attard G, Murphy L, Clarke NW, Cross W, Jones RJ, Parker CC, et al. Abiraterone acetate and prednisolone with or without enzalutamide for high-risk non-metastatic prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of primary results from two randomised controlled phase 3 trials of the STAMPEDE platform protocol. Lancet. 2022;399:447–60.

Acknowledgements

Tamás Fazekas received the following grants: the EUSP Scholarship of the European Association of Urology (Scholarship S-2023-0006), the New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology from the source of the National Research Development, and Innovation Fund (ÚNKP-22-3-1-SE-19).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM and TY contributed to protocol/project development, data collection and management, data analysis, and manuscript writing/editing. KB, MP, EL, JK, SC, KM, SK, TF, and MM contributed to manuscript writing/editing. JM, TFWS, TZ, DT, SJ, and TK contributed to the manuscript editing. PR and SFS contributed to supervision and manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Takahiro Kimura is a paid consultant/advisor of Astellas, Bayer, Janssen and Sanofi. Shahrokh F. Shariat received follows: Honoraria: Astellas, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Ferring, Ipsen, Janssen, MSD, Olympus, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda. Consulting or Advisory Role: Astellas, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Ferring, Ipsen, Janssen, MSD, Olympus, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Takeda. Speakers Bureau: Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, BMS, Ferring, Ipsen, Janssen, MSD, Olympus, Pfizer, Richard Wolf, Roche, Takeda. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript. Pawel Rajwa is a paid consultant/advisor of Janssen.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsukawa, A., Yanagisawa, T., Fazekas, T. et al. Salvage therapies for biochemical recurrence after definitive local treatment: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and network meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 28, 610–622 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-024-00890-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-024-00890-4

This article is cited by

-

Auffällige Kontrastmittelkinetik bei muzinösem Prostatakarzinom

Die Urologie (2025)