Abstract

Background and objective

Intraoperative identification of suspicious lymph node metastases (LNM) detected at PSMA-PET is key to achieve optimal surgical outcomes of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) with pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND). We aim to describe a novel technique of augmented reality (AR)-PSMA-3D guided PLND based on preoperative PSMA-PET for real-time identification of LNM.

Methods

Thirteen patients with high-risk PCa and miN1-2 or miM1a disease at PSMA-PET were prospectively enrolled. 3D segmentation model including suspicious LNM was created from PSMA-PET images.

Intervention

Patients underwent RARP with AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND for real-time intraoperative identification of suspicious LNM. Pathologic examination was used as reference standard.

Key findings and limitations

Four (30%) men had suspicious LNM at PSMA-PET outside the field of the PLND template. The AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND allow to dissect each region with suspected LNM at PSMA-PET with no intraoperative complications. Nine (69%) patients had pN1 disease and three (23%) men had nodal metastases outside the PLND template. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and AUC of AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND at a per-region analysis were 69%, 90%, 52%, 95% and 0.79, respectively. Limitations: low spatial resolution of PSMA-PET for micro-metastases and the need for manual alignment of the 3D model.

Conclusions and clinical implications

AR-PSMA-3D guidance for PLND in patients with miN1-N2-M1a disease at PSMA-PET allows to facilitate the resection of suspicious LNM including those outside the PLND template.

Patient summary

We propose a novel technique combining AR and PSMA-PET 3D models to guide PLND during RARP in PCa patients. The AR-PSMA-3D guidance for PLND allows a promising real-time identification of suspicious nodes, even outside the PLND template.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

PSMA-PET (Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Positron Emission Tomography) is increasingly adopted to improve Prostate Cancer (PCa) staging due to higher diagnostic accuracy that may overcome limitations of conventional imaging [1, 2]. Indeed, current 2024 EAU guidelines recommend to replace conventional imaging with PSMA-PET in high-risk disease [2]. As a consequence, in the modern cohorts using PSMA-PET for staging PCa, the rate of cN1 disease is up to 35% compared to 10% [3] reported in the historical cohort using conventional imaging only [4]. Moreover, the role of local therapies, including surgery in PCa patients with cN1 disease at PSMA-PET, has scarcely been explored [5], despite increasing evidence suggesting that the cytoreductive effect of local treatments could improve survival in men with metastatic disease [6, 7]. Indeed, the optimal management of these patients represents a matter of debate since incoming evidence from SPCG-15 trial that is still recruiting [8].

However, identifying the pathologic PCa tissue among the surrounding healthy structures provides a key challenge [9]; during surgery, even with an extended template for pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND), lymph node metastases (LNM) may be missed [10], in case of uncommon localization or inability to identify suspicious nodes during dissection due to the small nodal size, scary fatty tissue or bleeding.

Intraoperative detection of suspicious lymph nodes has been analyzed via different technologies [9], including fluorescence cameras [11] in combination with gamma probes [12, 13] or pure RGS [14, 15], that may be limited by further injection of radioisotopes, radiation exposure, and the need of intraoperative adoption of gamma/beta detectors.

We aimed to describe a novel technique of augmented reality (AR)-PSMA-3D guided PLND based on preoperative PSMA-PET which is displayed as AR overlay for real-time intraoperative identification of LNM in primary PLND during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) in high-risk PCa patients.

Materials

Study design

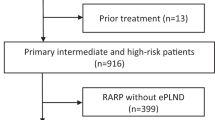

This was a single institution, non-comparative, prospective study. We prospectively enrolled high-risk PCa patients with no evidence of nodal or distant metastases (cN0M0) at conventional imaging and molecular imaging (mi) N1-2 or miM1a disease at PSMA-PET, scheduled for RARP and PLND. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice after Institutional Ethics Committee (IRB approval 4325/2017) and informed consent was obtained from each patient. Exclusion criteria were absolute contraindications for robotic surgery, miN0 or miM1b-c at preoperative PSMA-PET and receipt of neoadjuvant therapies.

Overall, 13 consecutive patients underwent RARP and AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND between December 2022 and June 2024.

Preoperative imaging

Within 30 days before surgery, all patients were staged as cN0M0 with conventional imaging (i.e., chest and abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography and bone scan). PSMA-PET was performed (according to standard procedures [16]) and interpreted by two experienced Nuclear Medicine physicians within 30 days from conventional imaging; PSMA-PET scans were reported according to PROMISE v2 criteria [17]. Only patients with miN1-2 or miM1a disease at preoperative PSMA-PET were enrolled for RARP with AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND. Patients with miN0 and miM0 disease underwent standard RARP and PLND.

3D Model reconstruction

All 3D virtual models were based on preoperative PSMA-PET. Segmentation was achieved using Mimics Medical software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium); semi-automatic tools (Threshold, Multiple Slice Edit, 3D Interpolate) of Mimics Medical software were adopted to segment the suspected pathologic lymph nodes based on PSMA-PET, the pelvic arteries (including distal portion of abdominal aorta with common iliac bifurcation, external and internal iliac arteries), the veins (including distal portion of inferior vena cava, common iliac bifurcation, external and internal iliac veins), pelvic ureters and pelvic bones based on preoperative abdominal CECT. Mimics Medical was also used to obtain the 3D virtual models (Fig. 1), as previously described [18, 19]. In case of unilateral nodal pelvic disease (miN1), the 3D model included anatomic structures of the ipsilateral side; in case of bilateral nodal pelvic disease (miN2) and common iliac/retroperitoneal nodes (miM1a) disease, the 3D model included bilateral anatomic landmarks.

The 3D virtual anatomical model is obtained starting from patient PSMA-PET (a), by the segmentation (b) of the anatomical regions of interest (pelvic arteries including distal portion of abdominal aorta with common iliac bifurcation, external and internal iliac arteries, veins including distal portion of inferior vena cava, common iliac bifurcation, external and internal iliac veins, pelvic ureters and pelvic bones) to the final 3D model (c).

Augmented Reality technology

Stereoscopic AR was applied to RARP using the DaVinci system, as previously described [20]. The stereoscopic AR system extracts the real-time feeds of the robotic endoscope cameras. These signals are acquired by an operative room (OR) desktop computer (PC) through two video capture cards (Startech USB 3.0 StarTech Ltd., The Netherlands). The real-time manual alignment between the preoperative virtual models and the intraoperative view (“AR image”) has been carried out by a biomedical engineer using a 6 degrees of freedom mouse (SpaceMouse, 3D Connexion, Munich, Germany; Fig. 2).

The OR PC then processes the two AR images (one for each camera) and transmits them to the DaVinci 3D viewer. These AR images are automatically merged to obtain a stereoscopic vision using the TilePro 3D function of the DaVinci system, which has been activated in the console.

Surgical technique

All patients underwent RARP and PLND using the four-arm DaVinci Xi Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California, USA) with a transperitoneal approach [3, 21].

PLND was performed after removal of the prostate gland: indeed, in case of intraoperative frozen section targeted to periprostatic tissue required to maximize resection and reduce positive surgical margins, the time for PLND allows pathologist to analyze surgical specimens in order to timing optimization.

Anatomically defined PLND was performed [22], and each anatomic region was sent separately for pathologic examination for a template-based analysis (i.e., external, internal, distal common iliac and obturator lymph nodes). Lymph nodes located in the extra-template field of PLND (including paravesical or pararectal or presacral or proximal common iliac nodes) were separately removed in case of suspicious uptake at PSMA-PET.

After dissection of external, distal common and internal iliac vessels including the pelvic ureter of each side in order to obtain visible anatomic landmarks, the 3D model was superimposed in the pelvic region using arterial and/or venal and/or ureteral landmarks manually adjusted to achieve ideal registration of contoured anatomical structures in order to properly localize suspicious lymph nodes at PSMA-PET (Fig. 3). Then, the AR-PSMA-3D technique is used to guide PLND and to excise separately the suspicious lymph nodes at PSMA-PET, including those with uncommon localization. In case of unilateral nodal pelvic disease (miN1), the AR-PSMA-3D guidance is used only for the dissection of ipsilateral pelvic nodes; in case of bilateral nodal pelvic (miN2) or common/retroperitoneal nodes (miM1a), the AR-PSMA-3D guidance is used for bilateral dissection of pelvic/retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

At PSMA-PET three suspicious pelvic lymph nodes are identified: presacral 12 × 6 mm (SUV max 7,5), right and left internal iliac (SUV max 3 and 2.2; a). The 3D model (b) is employed with reconstruction of pelvic arteries and veins, ureters, pelvic bones and 3 suspicious lymph nodes based on preoperative PSMA-PET. AR-PSMA-3D technology was used to facilitate removal of suspicious lymph nodes during robotic PLND (c). Final pathology revealed 2 out 17 nodal metastases (15 mm presacral and 5 mm right internal iliac) both with high PSMA expression (score 3+) at immunohistochemistry analysis (d).

Histopathological examination

All the pathological examinations, including the suspicious lymph nodes at PSMA-PET, all regions of anatomical template for PLND and extra-template lymph nodes were performed by a single dedicated uropathologist. The whole-mount histological examinations from the prostate specimens were performed following a prostate map [18, 19]. PSMA immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was conducted with automatic IHC staining instrument Benchmark Ultra (Ventana/Roche Group 1910 Innovation Park, Tucson, Arizona, AZ 85755 USA) both on prostate specimens and pathologic lymph nodes [23]. PSMA IHC positivity as visual score was graded in a four-tiered system according to the intensity of the stain, as follows: 0 = negative, 1+ = weak, 2+ = moderate and 3+ = strong.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

Intraoperative outcomes, which included overall operative time, PLND operative time, blood loss and intraoperative complications were collected during surgery; postoperative outcomes, including, length of stay, urethral catheter removal and 30-d postoperative complications, were prospectively collected during postoperative consultations according to the EAU Guidelines Panel recommendations [24].

The final pathologic evaluation was considered the gold standard to assess the diagnostic performance of AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND targeted to suspicious nodes at PSMA-PET for the identification of LNM. The first PSA measurement was performed at 40-d after surgery and PSA persistence was defined as a PSA value of >0.1 ng/ml. Patients with pN1 disease and those with PSA persistence were scheduled for postoperative treatment intensification, including pelvic radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy.

Medians and proportions were reported for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Contingency tables were used to calculate the sensitivity, specificity, positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive values and ROC curve analysis was performed to assess accuracy of AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND to detect LNM compared with final pathology in per-region analyses. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, US) for Mac.

Results

Table 1 depicts the overall preoperative patients’ characteristics. According to PROMISE criteria, stage disease at PSMA-PET was miN1 in six (46.6%), miN2 in six (46.6%) and miM1a in one (7.7%) patient. At preoperative PSMA-PET, four (30%) patients had suspicious nodes outside PLND template (Fig. 4a).

The AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND allow to dissect each region with suspected nodal metastases detected by preoperative PSMA-PET with no intraoperative complications and no need of surgical conversion (Table 2). Median operative time, PLND time, AR PSMA-3D model overlapping time during PLND were 210 min 75 min and 21 min, respectively. One patient had a postoperative lymphocele treated with percutaneous drainage (Clavien grade 3). Overall, two (15%), two (15%), eight (62%) and one (7%) patient had pT2, pT3a, pT3b and pT4 disease at pathologic examination, respectively. Overall, nine (69%) patients had pN1 disease with median 2 positive nodes: six men (46%) had LNM in the anatomical region inside the PLND template; three (23%) patients had LNM in the anatomical region outside the PLND template. At a median follow-up of 11 months, five patients had PSA persistence.

A total of 117 nodal region were separately resected, which included 242 lymph nodes. Overall, 15 of the 117 resected pelvic nodal regions (12.8%) and 31 of the 242 pelvic lymph nodes had LNM at final pathology (Fig. 4b). Supplementary Table 1 showed the site of positive lymph nodes at PSMA-PET and at pathologic examination on per-lymph nodes analyses over a total of 242 removed lymph nodes.

PSMA-PET identified 23 positive spots in 21 regions and final pathologic examinations revealed 31 nodal metastases in 15 regions. Overall, four patients had no LNM despite positive PSMA-PET. Moreover, PSMA-PET missed 4 positive regions (Table 3). Median size of nodal metastasis was 10 mm in region with LNM detected by AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND; while median size of nodal metastases was 5 mm in region with positive LNM not detected by AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND. However, the PSMA expression at IHC analysis was high (3 score) in all pathologic lymph nodes.

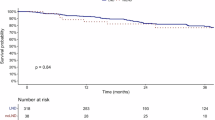

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and AUC of AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND to detect LNM at a per-region analysis were 69%, 90%, 52%, 95% and 0.79, respectively (Table 4 and Fig. 5).

Discussion

The optimal management of cN1 patients still represents a matter of debate. Current 2024 EAU guidelines [25] consider only radiotherapy as local treatment for cN1 disease; however, most evidences supporting radiotherapy are based on cN1 patients at conventional imaging. Conversely, the burden of cN1 disease at PSMA-PET is supposed to be lower to that of cN1 men at conventional imaging due to higher diagnostic accuracy of PSMA-PET even for small nodal metastases [26]. Thus, with increasing adoption of PSMA-PET, a significant proportion of patients would be diagnosed with “minimal” miN1-2 disease at PSMA-PET and cN0 at conventional imaging.

Despite no significant survival advantage has been provided by extended PLND [27], identifying LNM among the surrounding healthy tissue provides a key challenge [9] and during surgery, even with an extended template of PLND, pathologic lymph nodes may be missed [10], thus requiring additional intensified postoperative management, including further PSMA-PET for restaging proposal and dose incrementation boost during salvage RT targeted to positive LNM. Moreover, most patients with pN1 disease need further intensified treatments (i.e., pelvic radiotherapy and ADT) that may increase intraoperative complications and risk of severe lymphoedema.

Intraoperative detection of suspicious lymph nodes has been analyzed via modern imaging and different technologies [9], including fluorescence cameras in combination with gamma probes [12, 13] or pure RGS using beta [25] and gamma [26] probes for beta or gamma-emitting radioisotopes designed to target PSMA expressed on PCa cells and to provide a surgical roadmap for intraoperative “real-time” image guidance in salvage nodal dissection [27, 28] or primary PLND [29] both with open [30] and robotic approach [31]. However, potential limitations of RGS consist of further injection of radioisotopes, radiation exposure of the personnel and the need of intraoperative adoption of gamma/beta detectors.

Several strengths of our study are noteworthy. First, our series represents the first proposed application of AR technology guided by 3D models based on PSMA-PET for the intraoperative identification of suspicious LNM during PLND in high-risk PCa patients as an alternative option to RGS. Till now, only one previous study from Canda et al. [32] provided a surgical dissection guided by 3D model derived from PSMA-PET to better identify the index lesion within the prostate and reduce positive surgical margins. Second, the AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND did not significantly increase overall and PLND surgical time, intraoperative and postoperative complications. 3D reconstruction may take from 2 to 3 h and it costs approximately 100 euros per single reconstruction, considering the software license fee and costs for human resources Third, the real-time overlay of 3D reconstruction of main pelvic vessels, ureters and pelvic bones within the PSMA-positive lymph nodes allowed to facilitate the identification and dissection of LNM outside the PLND template in 3 cases (23%). However, while the median number of positive lymph nodes at PSMA-PET was 1, the median number of LNM at PLND was 2, thus underling that PSMA-PET may understate the nodal burden and ideal candidates for AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND (i.e., number, site, SUVmax and localization of suspicious nodes at PSMA-PET) need to be clarified. Fourth, despite a good overall diagnostic performance on per-region analysis (specificity of 90% and AUC of 0.79), the AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND still depicted suboptimal sensitivity (69%), comparable with previous reports [31], thus underlining the limitation of PSMA-PET derived technologies to identify micro-metastases. Of note, at IHC analysis all the pathologic lymph nodes showed high PSMA expression (score 3+) even those not detected at preoperative PSMA-PET. Indeed, the median size of LNM not detected by PSMA-PET was 5 mm; thus, the main cause of false negative findings of PSMA-PET was more related to the spatial resolution than the low PSMA expression. Finally, the AR-PSMA-3D approach allows to avoid further injection of additional radiotracers needed with RGS with potential risk for patients and radioactive exposure to surgical team and the use of specific gamma or beta probes that require learning curve and extra costs.

Despite several strengths, our study is not devoid of limitations. First, the limited number of patients included reduce the strengths of our findings. Second, further long-term oncologic follow-up is needed to assess the real oncologic benefit of AR-PSMA-3D guidance during primary PLND in miN1-N2 and miM1a Pca. Third, contrarily to RGS, our technique did not allow for immediate intraoperative feedback on the removal of all PSMA-avid tissue identified by preoperative PSMA-PET and may detect even small nodal metastases not detected at preoperative PSMA-PET. Fourth, on per-region analysis, false negative findings at PSMA-PET limited the diagnostic performance of AR-PSMA-3D guided PLND since 3D models suffer from the spatial resolution of PSMA-PET (>5 mm); indeed, the size of LNM in the region not detected by PSMA-PET was 5 mm. Fifth, postoperative PSMA-PET scans would be desirable to confirm improved intraoperative surgical resection of the pre-operative positive LNM compared to preoperative PSMA-PET; however, PSMA-PET was repeated after surgery only in case of PSA persistence to guide salvage treatments. Final limitations of AR-assisted surgery deal with the need of a bioengineer in OR for virtual-to-real registration and the possible registration inaccuracy, mainly due to manual registration, suboptimal overlapping using anatomic landmarks that may vary from preoperative imaging and tissue deformation during surgery.

Conclusions

The proposed technique of AR-PSMA-3D guidance for PLND in Pca patients with miN1-N2-M1a disease at PSMA-PET allows to facilitate the resection of suspicious LNM even outside the template of PLND. AR-PSMA-3D guidance may be used as a real-time intraoperative roadmap for PLND as alternative to RGS without the need of injection of further radioisotope or radiation exposure; however, the diagnostic accuracy for detection of micro-metastases is affected by the spatial resolution of PSMA-PET and manual registration of 3D models may limit the surgical precision.

Data availability

All datasets on which the conclusions of the paper rely are available to readers.

References

Hofman MS, Lawrentschuk N, Francis RJ, Tang C, Vela I, Thomas P, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA): a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet. 2020;395:1208–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30314-7.

Mottet N, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Cumberbatch MG, De Santis M, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer-2020 update. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2021;79:243–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURURO.2020.09.042.

Porreca A, Salvaggio A, Dandrea M, Cappa E, Zuccala A, Del Rossoet A, et al. Robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy with the use of barbed sutures. Surg Technol Int. 2017;30:39–43.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17–48. https://doi.org/10.3322/CAAC.21763.

Mazzone E, Gandaglia G, Robesti D, Rajwa P, Rivas JG, Ibáñez L, et al. Which patients with prostate cancer and lymph node uptake at preoperative prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography/computerized tomography scan are at a higher risk of prostate-specific antigen persistence after radical prostatectomy? Identifying indicators of systemic disease by integrating clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and functional imaging parameters. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024;7:231–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EUO.2023.08.010.

Parker CC, James ND, Brawley CD, Clarke NW, Hoyle AP, Ali A, et al. Radiotherapy to the primary tumour for newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer (STAMPEDE): a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2353–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32486-3.

Rajwa P, Robesti D, Chaloupka M, Zattoni F, Giesen A, Huebner NA, et al. Outcomes of cytoreductive radical prostatectomy for oligometastatic prostate cancer on prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography: results of a multicenter European study. Eur Urol Oncol. 2024;7:721–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EUO.2023.09.006.

Gongora M, Stranne J, Johansson E, Bottai M, Karlsson CT, Brassoet K, et al. Characteristics of patients in SPCG-15—a randomized trial comparing radical prostatectomy with primary radiotherapy plus androgen deprivation therapy in men with locally advanced prostate cancer. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2022;41:63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EUROS.2022.04.013.

Berrens AC, Knipper S, Marra G, van Leeuwen PJ, van der Mierden S, Donswijket ML, et al. State of the art in prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted surgery—a systematic review. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2023;54:43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EUROS.2023.05.014.

Hall WA, Paulson E, Davis BJ, Spratt DE, Morgan TM. NRG Oncology Updated International Consensus Atlas on pelvic lymph node volumes for intact and postoperative prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2021;109:174–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJROBP.2020.08.034.

Stibbe JA, Linders DGJ, Vahrmeijer AL, Bhairosingh SS, Bekers EM, van Leeuwenet PJ, et al. First-in-patient study of OTL78 for intraoperative fluorescence imaging of prostate-specific membrane antigen-positive prostate cancer: a single-arm, phase 2a, feasibility trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:457–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00102-X.

van den Berg NS, Buckle T, KleinJan GH, van der Poel HG, van Leeuwen FWB. Multispectral fluorescence imaging during robot-assisted laparoscopic sentinel node biopsy: a first step towards a fluorescence-based anatomic roadmap. Eur Urol. 2017;72:110–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURURO.2016.06.012.

Mazzone E, Dell’Oglio P, Grivas N, Wit E, Donswijk M, Briganti A, et al. Diagnostic value, oncologic outcomes, and safety profile of image-guided surgery technologies during robot-assisted lymph node dissection with sentinel node biopsy for prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2021;62. https://doi.org/10.2967/JNUMED.120.259788.

Maurer T, Robu S, Schottelius M, Schwamborn K, Rauscher I, van den Berget NS, et al. 99mTechnetium-based prostate-specific membrane antigen-radioguided surgery in recurrent prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2019;75:659–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURURO.2018.03.013.

Knipper S, Tilki D, Mansholt J, Berliner C, Bernreuther C, Steuber T, et al. Metastases-yield and prostate-specific antigen kinetics following salvage lymph node dissection for prostate cancer: a comparison between conventional surgical approach and prostate-specific membrane antigen-radioguided surgery. Eur Urol Focus. 2019;5:50–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EUF.2018.09.014.

Fendler WP, Eiber M, Beheshti M, Bomanji J, Calais J, Ceci F, et al. PSMA PET/CT: joint EANM procedure guideline/SNMMI procedure standard for prostate cancer imaging 2.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2023;50:1466–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00259-022-06089-W.

Seifert R, Emmett L, Rowe SP, Herrmann K, Hadaschik B, Calais J, et al. Second version of the prostate cancer molecular imaging standardized evaluation framework including response evaluation for clinical trials (PROMISE V2). Eur Urol. 2023;83:405–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURURO.2023.02.002.

Bianchi L, Chessa F, Angiolini A, Cercenelli L, Lodi S, Bortolani B, et al. The use of augmented reality to guide the intraoperative frozen section during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2021;80:480–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURURO.2021.06.020.

Schiavina R, Bianchi L, Lodi S, Cercenelli L, Chessa F, Bortolani B, et al. Real-time augmented reality three-dimensional guided robotic radical prostatectomy: preliminary experience and evaluation of the impact on surgical planning. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7:1260–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EUF.2020.08.004.

Tartarini L, Riccardo S, Bianchi L, Lodi S, Gaudiano C, Bortolani B, et al. Stereoscopic augmented reality for intraoperative guidance in robotic surgery. J Mech Med Biol. 2023;23. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219519423400407.

Porreca A, D’agostino D, Dandrea M, Salvaggio A, Del Rosso A, Cappa E, et al. Bidirectional barbed suture for posterior musculofascial reconstruction and knotless vesicourethral anastomosis during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2018;70:319–25. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0393-2249.18.02969-7.

Gandaglia G, Ploussard G, Valerio M, Mattei A, Fiori C, Fossati N, et al. A novel nomogram to identify candidates for extended pelvic lymph node dissection among patients with clinically localized prostate cancer diagnosed with magnetic resonance imaging-targeted and systematic biopsies. Eur Urol. 2019;75:506–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURURO.2018.10.012.

Vetrone L, Mei R, Bianchi L, Giunchi F, Farolfi A, Castellucci P, et al. Histology and PSMA expression on immunohistochemistry in high-risk prostate cancer patients: comparison with 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT features in primary staging. Cancers. 2023;15. https://doi.org/10.3390/CANCERS15061716.

Gandaglia G, Bravi CA, Dell’Oglio P, Mazzone E, Fossati N, Scuderi S, et al. The impact of implementation of the European Association of Urology Guidelines Panel Recommendations on reporting and grading complications on perioperative outcomes after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2018;74:4–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURURO.2018.02.025.

Cornford P, Tilki D, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Eberli D, De Meerleer G, et al. Guidelines on prostate cancer. 2024. https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG-Guidelines-on-Prostate-Cancer-2024_2024-04-09-132035_ypmy_2024-04-16-122605_lqpk.pdf.

Hope TA, Eiber M, Armstrong WR, Juarez R, Murthy V, Lawhn-Heath C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET for pelvic nodal metastasis detection prior to radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection: a multicenter prospective phase 3 imaging trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1635. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMAONCOL.2021.3771.

Touijer KA, Sjoberg DD, Benfante N, Laudone VP, Ehdaie B, Eastham JA, et al. Limited versus extended pelvic lymph node dissection for prostate cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Urol Oncol. 2021;4:532–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EUO.2021.03.006.

Rauscher I, Düwel C, Wirtz M, Schottelius M, Wester HJ, Schwamborn K, et al. Value of 111 In-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-radioguided surgery for salvage lymphadenectomy in recurrent prostate cancer: correlation with histopathology and clinical follow-up. BJU Int. 2017;120:40–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/BJU.13713.

Gondoputro W, Scheltema MJ, Blazevski A, Doan P, Thompson JE, Amin A, et al. Robot-assisted prostate-specific membrane antigen-radioguided surgery in primary diagnosed prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2022;63:1659–64. https://doi.org/10.2967/JNUMED.121.263743.

Knipper S, Budäus L, Graefen M, Maurer T. Prostate-specific membrane antigen radioguidance for salvage lymph node dissection in recurrent prostate cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2021;7:294–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EUF.2021.01.015.

Knipper S, Ascalone L, Ziegler B, Hohenhorst JL, Simon R, Berliner C, et al. Salvage surgery in patients with local recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2021;79:537–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EURURO.2020.11.012.

Canda AE, Aksoy SF, Altinmakas E, Koseoglu E, Falay O, Kordan Y, et al. Virtual reality tumor navigated robotic radical prostatectomy by using three-dimensional reconstructed multiparametric prostate MRI and 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT images: a useful tool to guide the robotic surgery?. BJUI Compass. 2020;1:108–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/BCO2.16.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Fondazione CARISBO of Bologna (Italy) for supporting the costs needed for 3D models reconstruction.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The work reported in this publication was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, RC-2023-2778936. Open access funding provided by Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: LB, RS, and EB. Acquisition of data: RS, MD, MR, PP, and FC. Analysis and interpretation of data: Drafting of the manuscript: LB, AM, BB, LC, and AF. Critical revision of the manuscript: AF, PC, and MF. Statistical analysis: AB, MB, FG, and MS. Supervision: SF, EM, CM, and CG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bianchi, L., Mottaran, A., Bortolani, B. et al. Augmented Reality PSMA-3D guided robotic pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) in prostate cancer patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-025-01024-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-025-01024-0

This article is cited by

-

Bridging the gap between PSMA-PET and reality: critical missing elements in AR-guided pelvic lymph node dissection

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2026)

-

Extraperitoneal robot-assisted radical prostatectomy with the Hugo™ RAS system: 100 consecutive cases, 1-year follow-up and surgical learning curve evaluation

Journal of Robotic Surgery (2025)