Abstract

Substance use disorders (SUDs) imposes profound physical, psychological, and socioeconomic burdens on individuals, families, communities, and society as a whole, but the available treatment options remain limited. Deep brain-machine interfaces (DBMIs) provide an innovative approach by facilitating efficient interactions between external devices and deep brain structures, thereby enabling the meticulous monitoring and precise modulation of neural activity in these regions. This pioneering paradigm holds significant promise for revolutionizing the treatment landscape of addictive disorders. In this review, we carefully examine the potential of closed-loop DBMIs for addressing SUDs, with a specific emphasis on three fundamental aspects: addictive behaviors-related biomarkers, neuromodulation techniques, and control policies. Although direct empirical evidence is still somewhat limited, rapid advancements in cutting-edge technologies such as electrophysiological and neurochemical recordings, deep brain stimulation, optogenetics, microfluidics, and control theory offer fertile ground for exploring the transformative potential of closed-loop DBMIs for ameliorating symptoms and enhancing the overall well-being of individuals struggling with SUDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Throughout most of history, individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs) have often been seen as having a personal weakness or moral deficiency, leading to stigma and negative labels such as “addict” or worse. SUDs represent a profound public health challenge and exerts a substantial economic strain on society. Results from the 2022 U.S.-based National Survey on Drug Use and Health revealed that 48.7 million individuals aged 12 or older experienced an SUD within the past year [1]. For the most frequently misused substance, alcohol, the likelihood of relapse at a year post-detoxification is approximately 70–80% [2], underscoring the limited effectiveness of conventional behavioral and pharmaceutical interventions. Progress in the field of neuroscience has deepened our insight into the brain alterations linked to this disorder, establishing the foundation for acknowledging SUDs as a continuous, enduring condition prone to relapse, yet responsive to treatment and rehabilitation [3]. However, it has also highlighted the pressing need for extensive exploration of innovative treatment modalities.

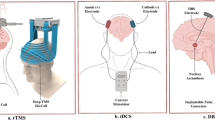

Brain-machine interfaces (BMIs) enable direct interaction between the human brain and the external world, bypassing peripheral nerves. They translate complex brain signals into computer commands, which can result in various outputs, such as movements or message transmission [4, 5]. Based on the different ways of collecting neural signals, BMIs can be categorized into two main types: non-invasive and invasive. As illustrated in Fig. 1A, a typical BMI process consists of consecutive steps including signal acquisition and processing, feature extraction and translation, device control, and feedback [6]. Non-invasive BMIs are advantageous in terms of safety, but they suffer from limited spatial resolution, hindering precise intervention and diagnosis. In contrast, invasive BMIs offer substantial benefits: they target cortical areas or subcortical structures and enable direct placement of electrodes into these regions, essential for decoding specific information and modulating distinct brain functions. Additionally, they provide higher spatial and temporal resolution of neural signals, even down to the activity of individual neurons or specific neuronal populations, as well as a superior signal-to-noise ratio and increased robustness against noise interference or motion artifacts [7]. To date, significant efforts have been dedicated to medical applications of invasive BMIs, with a primary focus on the restoration of motor function in individuals experiencing paralysis [8, 9]. Notably, the cerebral cortex has served as the predominant focal point of investigation for relevant research endeavors. However, the treatment of numerous neurological and psychiatric disorders often necessitates and is applicable to the modulation of deep brain structures. As an illustration, SUDs are associated with observable structural and functional anomalies within deep brain structures such as the nucleus accumbens (NAc) [10]. The emerging field of deep BMIs (DBMIs), a subclassification of invasive BMIs, which emphasizes the comprehension and manipulation of neural activities within deep brain structures, holds immense potential for the treatment of SUDs [11]. Advanced DBMIs possess the capability to selectively modulate deep brain structures and address pathological states by employing responsive or adaptive therapeutic stimulations tailored to identified biomarkers. This closed-loop brain stimulation approach offers a remarkable opportunity for providing individualized treatment to patients with SUDs.

This review seeks to evaluate the feasibility and underlying mechanisms of DBMIs in the treatment of SUDs, placing special emphasis on addictive disorders-related biomarkers, stimulation delivery and control policies. We cautiously contend that DBMIs hold great promise for revolutionizing the treatment of SUDs, offering novel perspectives for future advancements.

A concise summary of neurobiology of SUDs

Addictive behaviors in SUDs can be defined as a three-stage cycle, encompassing binge/intoxication, withdrawal/negative affect, and craving/anticipation, which worsens over time. Animal experimentation and human imaging studies have unveiled a diverse array of brain structures and neurochemical substances that play a crucial role in mediating the three stages of the cycle [12]. The principal brain structures involved in these processes encompass the ventral tegmental area (VTA), NAc, subthalamic nucleus (STN), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), striatum, amygdala, hippocampus, and insula, among a host of others (Fig. 2A, B) [13]. The mesolimbic dopaminergic reward system occupies a central position in the development of SUDs, with impaired function within this system representing a pivotal hallmark of drug addiction. Dopamine, which is critical for cognitive processes such as decision making and action planning, serves as a key driver for reinforcing behaviors linked to rewards and positive emotions. Essentially, addictive substances have a pronounced and rapid impact on elevating synaptic dopamine concentrations in subcortical brain structures, such as the NAc, surpassing the capacity of natural rewards and gradually leading to a decline in dopamine system functioning [14]. For example, studies have linked the rewarding effects of alcohol to dopamine release and transmission in the NAc. Notably, alcohol induces a significant 25% to 50% surge in extracellular dopamine concentrations [15]. Such Pavlovian conditioning of drug-environmental cues can elicit an insatiable drive to procure additional doses of the substance. The increase in dopamine in the brain due to SUDs primarily occurs through two mechanisms: (i) activation of dopamine neurons and (ii) facilitation of dopamine release at nerve endings or blockade of dopamine reuptake. Research indicates that opioids, another class of frequently misused substances, exert their rewarding effects by amplifying the activity of dopamine neurons in the VTA and promoting the release of dopamine in the NAc [16].

A The sagittal plane; B The coronal plane. CN: Caudate nucleus; GP: Globus pallidus; HPC: Hippocampus; Ip: Insula and putamen; LN: Lentiform nucleus; mPFC: Medial prefrontal cortex; NAc: Nucleus accumbens; STN: Subthalamic nucleus; VTA: Ventral tegmental area. Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.

Intriguingly, dopamine coreleases with glutamate in the NAc, VTA, and PFC. Glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter heavily involved in synaptic plasticity, enhances rewarding effects in SUDs and promotes substance dependence. Addictive substances exert their effects on glutamate transmission through distinct mechanisms. Cocaine activates dopamine D1 receptors, while heroin and alcohol achieve this effect by reducing the inhibitory influence of GABAergic neurons [17, 18].

Serotonin (also known as 5-HT), another crucial neurotransmitter, plays a significant role in regulating brain development, a wide range of physiological functions, and the control of normal and pathological behaviors [19]. Dysregulation of serotonin metabolism can lead to a lack of pleasure and depression during drug withdrawal, triggering drug-seeking behavior [20]. Notably, the involvement of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors in the PFC, NAc, and VTA closely influences dopamine modulation. Increased activity of 5-HT2A receptors along with decreased activity of 5-HT2C receptors in the striatum promotes dopamine release [21]. Furthermore, in rats, the use of a 5-HT1B receptor agonist has been shown to reduce cocaine self-administration following a prolonged period of abstinence and relapse [22]. Similarly, emerging findings in mice indicate that serotonin signaling through the 5-HT1B receptor may mitigate the progression from occasional to compulsive cocaine use [23].

Intelligent closed-loop DBMI systems

Previous research in the field of BMIs for motor function rehabilitation primarily concentrated on decoding brain signals to manipulate external devices. However, in the context of DBMIs, particularly when used to treat neuropsychiatric disorders, the ability to modulate brain function becomes highly significant. The standard clinical protocols for employing DBMIs, such as deep brain stimulation (DBS), often adopt an “open-loop” and “one-size-fits-all” paradigm, whereby the stimulation parameters (e.g., intensity, frequency, and duration) are predetermined and remain invariant, irrespective of an individual’s unique brain physiology or pathological condition [16]. However, brain function and disease states are intrinsically dynamic, and the utilization of nonspecific stimulation patterns can engender the development of “tolerance” phenomena, thereby diminishing the effectiveness of modulation and potentially disrupting the normal functions of targeted brain structures, giving rise to undesired side effects [10, 24]. Furthermore, identical stimulation protocols may ignite heterogeneous effects owing to inherent interindividual disparities, thus posing challenges to achieving the intended level of neural function recovery among patients. As a result, closed-loop neuromodulation techniques have emerged as a solution, being categorized into two types based on the therapeutic requirements of the relevant diseases [25]. The first type is responsive neurostimulation, which employs a stimulus delivery paradigm triggered by specific conditions and states. This approach necessitates a reactive interaction with the neural system when intervention efficacy is contingent upon specific states. For example, compared to open-loop vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), closed-loop left cervical VNS, initiated by a seizure-related heart rate increase, can more effectively reduce seizure frequency and severity [26, 27]. The second type is adaptive neuromodulation, which dynamically adjusts stimulation parameters based on monitored indicators to optimize the effectiveness of the intervention. This type of modulation is essential when the physiological or clinical outcomes of neuromodulation cannot be reliably anticipated and when monitoring and optimization of the intervention parameters are needed. An illustrative example of adaptive neuromodulation is the employment of closed-loop spinal cord stimulation to alleviate pain and concomitant symptoms in individuals suffering from back or leg pain. In such scenarios, the stimulation parameters are fine-tuned through feedback mechanisms, leveraging evoked compound action potentials, thus facilitating tailored therapeutic outcomes [28]. Moreover, closed-loop neuromodulation techniques have been shown to be effective in treating a range of medical conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease [29], essential tremor [30, 31], and treatment-resistant depression [32], yielding promising results. Unlike open-loop neuromodulation system, closed-loop neuromodulation systems not only have the potential to extend the battery life and enhance device safety but also assist in achieving specific therapeutic goals. In their study, Salam et al. demonstrated in a rodent model of epilepsy that the battery life of closed-loop implant devices was 35 times higher than that of open-loop methods [33]. This advantage stems from the fact that stimulation is delivered only when necessary, and the stimulation parameters can be customized and adjusted according to individual needs.

Indeed, the advent of DBMI technology has presented novel prospects for the establishment of closed-loop neuromodulation systems. A typical closed-loop DBMI system entails the integration of three fundamental components (Fig. 1B) [16, 25]: (i) a sensing module, responsible for the identification and precise measurement of disease-specific biomarkers; (ii) a stimulation module, entrusted with the delivery of customized stimulation patterns; and (iii) a control/algorithm module, tasked with governing the intricacies of stimulation intensity and timing. Notably, the successful implementation of a closed-loop DBMI modulation strategy hinges upon several pivotal considerations, including the identification of robust biomarkers, the meticulous selection of stimulation modalities and targets, and the formulation of optimal stimulation control policies [34,35,36]. Moving forward, we will explore the evidence on, untap the potential of, and offer a forward-looking perspective on the application of closed-loop DBMIs in the realm of the treatment of SUDs.

Closed-loop DBMIs in SUDs

Despite the limited availability of direct evidence thus far, studies on the application of closed-loop DBMIs in treating other diseases have hinted at its potential utility in addressing SUDs. Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent episodes of consuming significantly large quantities of food, accompanied by a sense of lacking control over one’s eating behavior [37]. Research indicates a high comorbidity rate between BED and SUD, with a U.S.-based nationally representative study reporting that up to 68% of individuals with BED have a lifetime history of SUD [38]. Indeed, BED and SUD share notable phenotypic similarities, including the inability to control consumption and the persistence of use in the face of negative outcomes [39]. Additionally, both BED and SUD exhibit similar neurobiological pathways, such as dysfunctional reward processing, cravings, emotional dysregulation, and impulsivity, prompting research into therapeutic drugs (e.g., Bupropion, Naltrexone) that target these shared mechanisms for the treatment of both disorders [40,41,42]. However, there are also significant differences; for example, concerns about body shape and weight can initiate and sustain problematic eating behaviors in some individuals, which is not a typical feature of the addiction viewpoint [39]. Nonetheless, the similarities between the two conditions suggest that the exploration of treatments for BED may contribute to a deeper understanding of SUDs treatment. In a pilot study involving two patients diagnosed with BED, the utilization of a closed-loop DBMI system for targeted stimulation of the NAc yielded a prompt reduction in food cravings and compulsive eating behaviors. This responsive neurostimulation delivery was guided by heightened low-frequency oscillations observed in the NAc during instances of food cravings. After six months of intervention, both subjects demonstrated significant improvements in terms of loss-of-control eating, as well as notable reductions in body mass index and weight [43]. The results of this study highlight the potential of closed-loop DBMI technology for ameliorating the conditions of individuals afflicted with SUDs.

A meta-analysis revealed a significant relationship between emotion regulation and substance use [44]. For instance, major depressive disorder (MDD), a common emotional disorder, frequently co-occurs with SUDs due to disruptions in shared neurobiological circuits and molecular mechanisms that regulate the reward pathways in both conditions [45]. MDD can lead to SUDs, while the coexistence of SUD may exacerbate MDD into treatment-resistant depression (TRD), or shared vulnerabilities and life experiences may increase the risk of both conditions [45, 46]. In conclusion, research on closed-loop DBMIs for the treatment of depression is significant, as it may contribute to the design of closed-loop systems for SUDs therapy and enhance the management of comorbidities. To date, preliminary results have been published on the use of closed-loop DBMI therapy in a 36-year-old woman with severe TRD who, despite not responding to combined antidepressant medication and electroconvulsive therapy, exhibited a robust response to closed-loop stimulation of the capsule/ventral striatum triggered by amygdala gamma activity [32]. Moreover, Sheth et al. have demonstrated that personalized DBS stimulation parameters, informed by intracranial electrophysiology, can enhance the neuromodulation of TRD [47].

Notably, open-loop stimulation methodologies, such as routine DBS, have already undergone extensive investigation within the realm of SUDs treatment [48,49,50]. Moreover, recent technological advancements have led to the emergence of innovative approaches for the identification of biomarkers, as well as neuromodulation strategies. Although these advancements may not serve as direct evidence for the application of closed-loop DBMIs in SUDs treatment, they provide support for its feasibility and offer valuable insights for the design and implementation of specialized closed-loop DBMI systems tailored for SUDs therapy.

Sensing biomarkers associated with cravings or seeking

Reliable biomarkers play a pivotal role in enhancing patient stratification, monitoring disease trajectory, evaluating therapeutic efficacy, and propelling advancements in closed-loop DBMI systems for SUDs intervention. Optimal biomarkers should be accessible while demonstrating an exceptional capacity for discerning fine temporal and spatial variations. Furthermore, their intimate correlation with clinical symptoms serves as a crucial factor. Among prospective candidates, objective electrophysiological and neurochemical indicators stand out as the most promising contenders (Fig. 3A).

A Microelectrode, local field potential and examples of electrochemical technologies. Left: Amperometry is used to determine glutamate levels. In this scenario, local glutamate is converted to H2O2 by glutamate oxidase. Subsequently, H2O2 breaks down into two hydrogen molecules and oxygen, releasing two electrons that boost the current recorded in the biosensor (platinum wire). Any interfering molecules are effectively blocked by Nafion. Right: Fast scan cyclic voltammetry determines dopamine. Dopamine undergoes a potential change cycle from −0.4 V to +1.3 V and back to −0.4 V, during which dopamine and dopamine-o-quinone mutually convert, promoting electron transfer. This electron transfer causes distinctive disturbances in the original voltammogram, facilitating the identification of specific neurotransmitters. a-KG: α–ketoglutarate; BSA: Bovine serum albumin; e-: electrons; DA: dopamine; DOQ: Dopamine-o-quinone; E (^): Varied voltage; Glu-Ox: Glutamate oxidase; Glut: glutaraldehyde; PT: Platinum wire. Image created with BioRender.com, with permission. This figure is protected by Copyright, is owned by Journal of Neurosurgery Publishing Group (JNSPG at thejns.org) and is used with permission only within this document. Permission to use it otherwise must be secured from JNSPG. Full text of the article containing the original figure is available at https://doi.org/10.3171/2010.5.FOCUS10110. B Different stimulation methods and devices. Image created with BioRender.com, with permission.

Electrophysiological biomarkers

In the realm of closed-loop DBMI electrophysiological measurements, the oscillatory rhythms of local field potentials (LFPs) have emerged as the most prevalent biomarkers under investigation [11]. LFPs encapsulate the cumulative effect of excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials near the electrode, thereby offering insights into the regularity and synchronization of neuronal ensembles [51]. The widespread adoption of LFPs can be primarily attributed to their accessibility, as they can be measured directly by the stimulating electrode itself. Neural oscillations, manifested as recurrent patterns of neural population activity across diverse frequency domains within the central nervous system, have been used to elucidate the fundamental mechanisms underpinning normal brain function [52]. Conventional practice dictates that neural oscillations are categorized into different frequency bands, including delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (15–30 Hz), gamma (30–90 Hz), and high gamma (>50 Hz) [53]. The term “craving” refers to the intense desire or compulsion to consume a certain substance during withdrawal, which manifests as drug/food-seeking behaviors and is considered a core feature of addictive disorders [54]. Substance-related cues, such as the smell of alcohol or the aroma of food, can trigger cravings, leading to further alcohol reuse or binge eating. Thus, a critical issue in closed-loop DBMIs for SUDs treatment is to discern biomarkers associated with cravings or drug/food-seeking behaviors amidst the backdrop of oscillatory rhythms in LFPs (Table 1).

Self-administration is an addiction animal model that possesses high construct, content, and face validity. In typical paradigms of this nature, animals actively press levers or touch buttons to acquire addictive substances [55]. Müller Ewald et al. found that rats displayed lower theta band power in the infralimbic cortex, a small region of the mPFC, when they were actively seeking cocaine than when they were not seeking it [56]. Ngbokoli et al. discovered that rats exhibited higher levels of cocaine craving when the power of low gamma (30–58 Hz) band in the NAc core was lower during the resting state following self-administration training [57].

Drug/food-induced conditioned place preference (CPP), another widely used animal model for studying reward and addiction, is a Pavlovian-based behavior [58]. In the CPP paradigm, addictive substances or enticing food are consistently paired with specific locations, leading animals to spend more time in those places during subsequent exploration. CPP measures the level of motivation for approaching a drug or food-associated environment, which represents a crucial stage in the process of seeking drugs or food [59]. Takano et al. discovered a correlation between the occurrence of hippocampal phase-locked theta activity in rats and exploratory behavior both before and after the establishment of cocaine-induced CPP. They also observed that the increased inclination toward approach behavior, driven by cocaine reward-related memories, can lead to a shortened latency in the onset of phase-locked theta activity. Additionally, once the rats entered the cocaine-associated side of the environment, the corresponding phase-locked theta activity ceased to exist. Such alterations in the theta band before and after seeking behavior are believed to signify the conclusion of exploratory activity and the preparedness for reward acquisition in the context of drug-induced preference [60]. In a study by Zhu et al., it was found that heroin-induced CPP leads to a noteworthy increase in the relative power of the theta band (4–8 Hz) and a decrease in relative gamma IV band (60–70 Hz) power, along with changes in theta-gamma coupling, in the LFPs of the mPFC prelimbic area in rats [61]. Moreover, it has been observed by Nukitram et al. that LFP oscillation in the basolateral amygdala is sensitive to craving and seeking behaviors triggered by methamphetamine (METH)-induced CPP, with significant reductions in theta (4.7–8.7 Hz; P = 0.010) and alpha (9.8–12.7 Hz; P = 0.025) band powers during the post-METH conditioning phase compared to the pre-METH conditioning phase [62]. Regarding food-induced CPP, Samerphob et al. found that the smell of chocolate as a conditional stimulus significantly increased slow delta (0.5–4 Hz; P < 0.001) and theta (4.5–12 Hz; P < 0.001) band powers of hippocampal CA1 LFP signals, indicating a heightened motivation to eat and predictive of feeding probability [63]. Further research adopting the same approach recorded additional LFP oscillation changes in various brain regions in response to chocolate cues, revealing that chocolate-experienced mice in the CPP apparatus exhibited a significant increase in delta band power (P < 0.05) in the lateral hypothalamus, as well as significant reductions in low (30.5–45 Hz; P < 0.001) and high (60–100 Hz; P < 0.001) gamma band powers. Furthermore, a significant decrease in high gamma band power (P < 0.05) was observed in the NAc [64]. Wu et al. discovered that in mice, a craving for a high-fat food reward was associated with an increase in delta band power in the NAc [65].

In the field of clinical trials, relevant research is scarce. A study conducted by Ge et al. investigated the oscillatory LFPs of the NAc and the anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC) in seven patients diagnosed with heroin use disorder [66]. The results revealed that, prior to DBS intervention, both the NAc and the ALIC exhibited significant activity in the theta and alpha frequency bands. Importantly, a significant negative correlation (P = 0.002) between the power of theta band oscillations in the ALIC and drug cravings, providing a potential theoretical foundation for adaptive neuromodulation. The alpha band power of the NAc LFPs was found to be significantly positively correlated with depressive symptoms (P = 0.005). However, a limitation of this study is that post-DBS LFPs of the NAc and the ALIC were not observed for comparison with pre-DBS recordings. Notably, the observation of similar delta band oscillations in the human NAc during the anticipation of high-fat food rewards, mirroring findings in mice, has contributed to the successful clinical pilot trials of closed-loop DBMIs in BED [43, 65]. However, despite the integration of animal and human studies, the most consistent electrophysiological biomarkers for SUDs remain unclear and require further research to elucidate. Additionally, studies investigating the electrophysiological changes induced by DBS in SUDs will provide further insights into obtaining optimal electrophysiological biomarkers.

Neurochemical biomarkers

Neurochemical recording has emerged as a novel approach for monitoring neural activity, enabling the measurement of various ions and neurotransmitters within the intricate nervous system. In comparison to traditional neuroelectric activity monitoring, neurochemical recording exhibits numerous advantages, such as enhanced specificity, reduced susceptibility to interference from other bioelectrical signals, and the direct evaluation of inhibitory and excitatory neural circuitry through the extracellular monitoring of specific neurotransmitter concentrations [67]. Moreover, when simultaneous recording of electrophysiological biomarkers and electrical stimulation occurs at the same spatial location, the resulting recorded signals may be significantly affected by pronounced stimulation artifacts originating from nearby stimulating electrodes. Conversely, a closed-loop DBMI system built upon the principles of neurochemical recording has the potential to yield invaluable insights into the impact of neuromodulation on target tissues, thereby offering enhanced comprehension of the intricate interplay between stimulus delivery and neural responses. The gold standard for monitoring neurochemical substances has traditionally been in vivo microdialysis, which offers a high level of specificity. However, this technique has limitations, including the need for external analytical equipment, low temporal and spatial resolution, and reduced feasibility of implantation [68]. On the other hand, electrochemical detection methods, such as amperometry and voltammetry, offer significant advantages due to the utilization of carbon fiber microelectrodes, which are approximately 20 times smaller than microdialysis probes. This reduction in size allows for higher spatial and temporal resolution capabilities, enabling precise and real-time monitoring of neurochemical substances. Additionally, these methods offer the potential to utilize implantable electrodes, further enhancing their applicability for long-term monitoring and research purposes. Nevertheless, these benefits are accompanied by a trade-off, namely, lower specificity for biomarkers.

Addiction research places a significant emphasis on the investigation of neurochemical substances, with a particular focus on monoamine neurotransmitters. Notably, dopamine, glutamate, and serotonin have garnered considerable attention due to their intricate involvement in addictive processes. Dopamine and serotonin can be directly detected by fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, as they are electroactive amines. However, nonelectrically active substances such as glutamate can be detected by modifying the sensing electrodes with selective membranes and enzymes, such as glutamate oxidase, enabling the conversion of the neurotransmitter into an electrochemically detectable compound for analysis [69]. The Wireless Instantaneous Neurochemical Concentration Sensor (WINCS) exemplifies the monitoring of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, glutamate, and serotonin in the nervous system, functioning as a single-channel wireless neurochemical feedback system within closed-loop DBMIs [70]. However, similar to WINCS, existing electrochemical detection systems are often restricted in their ability to monitor only one neurotransmitter at a time in a specific location. With the advancement of advanced manufacturing strategies, WINCS technology has evolved into the WINCS Harmon system, which possesses the capabilities of synchronized stimulation and multichannel neurochemical recording. To date, it has been demonstrated to measure neurochemical activity in multiple anatomical targets simultaneously in nonhuman primates, pigs, and rodents [71]. Moreover, Li et al. recently successfully engineered an innovative and soft neural interface known as NeuroString, utilizing a graphene-based biosensing platform that mimics the properties of human tissue, which enables long-term and real-time monitoring of multiple monoamine neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and serotonin, in the brains of live animals. NeuroString boasts the capability to perform multichannel and multiplexed sensing, making it possible to simultaneously detect and analyze numerous biomarkers at different locations within the brain. In comparison to conventional rigid probes, stretchable NeuroString demonstrates enhanced biocompatibility and reduced adverse tissue reactions [72].

Interestingly, there is a potential relationship between neurochemical and electrophysiological biomarkers. For instance, studies have shown that modulating the dopamine or serotonin systems can regulate theta and gamma rhythms in the hippocampus-mPFC pathway [73]. Further research into the interaction between neurochemical and electrophysiological biomarkers is needed to uncover the underlying complex mechanisms of SUDs and identify more precise biomarkers.

Delivery of stimulation

According to different mechanisms of action, methods for stimulation modes in closed-loop DBMIs include DBS, optogenetic stimulation, and pharmacological stimulation (Fig. 3B).

DBS

With progressive advancements in the field of functional neurosurgery, there is a growing recognition of the therapeutic potential of DBS technology in addressing SUDs. Numerous preclinical studies have been conducted on the use of DBS for addiction treatment, and several completed clinical trials have investigated the safety and efficacy of DBS in treating SUDs involving alcohol [74,75,76], opioids [77,78,79,80], methamphetamine/amphetamines [81, 82], and BED [43], among others. Wang et al., Chang et al., and Yuen et al. conducted comprehensive reviews on the relevant research regarding DBS for SUDs treatment [10, 16, 83]. The target regions modulated in the relevant studies encompass the NAc, dorsolateral striatum, subthalamic nucleus, mPFC, and others. Among these, the NAc stands out as the most extensively researched and promising target, while the mPFC emerges as another auspicious candidate. However, it is worth noting that the current understanding of using DBS for SUDs primarily relies on case series or reports, which suffer from limitations including a lack of standardized outcome reporting, limited long-term follow-up, and the absence of blinding measures. In a study by Gonçalves-Ferreira et al., a double-blind methodology was employed to investigate the treatment of cocaine addiction using DBS targeted at the NAc [84]. While double-blind studies and sham surgeries have research potential, ethical considerations arise due to potential risks to patients without assured therapeutic benefits.

The specific mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of DBS in SUDs treatment have not yet been fully elucidated. However, from the perspective of leveraging the progress in DBS for other neurologic conditions, such as major depressive disorder and Parkinson’s disease, DBS is believed to exert its therapeutic effects through various mechanisms. DBS has been suggested to exert its effects by inhibiting local neurons, as indicated by animal studies. The injection of GABA agonists in the NAc and high-frequency DBS have demonstrated similar effects, both leading to a reduction in alcohol consumption in rats [85]. Additionally, similar effects have been observed with STN lesions and DBS stimulation in the presence of cocaine [86, 87]. One potential mechanism is that DBS promotes synaptic inhibition by enhancing GABA release, thus suppressing downstream neurons [88, 89]. Another possible mechanism is the synaptic depletion hypothesis, which proposes that high-frequency stimulation may deplete neurotransmitters, inhibiting output from the stimulated neurons. Moreover, DBS is considered to exert therapeutic effects by interrupting pathological neural oscillations, modulating neural plasticity, and facilitating dopamine replacement [10, 16].

Optogenetic stimulation

Optogenetics integrates optical and genetic techniques to manipulate neural activity by genetically modifying neurons to express photosensitive proteins known as opsins [90]. When these opsins are illuminated with specific wavelengths of light, they induce excitatory or inhibitory activity in the corresponding neurons. Unlike DBS, optogenetic techniques provide the ability to selectively stimulate specific populations of neurons at desired time points, allowing for the regulation of neural activity and synaptic transmission within identified circuit nodes with higher resolution, without interfering with the recording of delicate neural electrical signals. To target specific regions in need of stimulation, an invasive probe called the optical probe, commonly integrated with electrodes known as an “optrode”, has been invented to enable closed-loop optogenetic modulation while recording changes in electrical signals [91]. Optogenetic stimulation has demonstrated significant therapeutic potential for SUDs treatment. For instance, Pascoli et al. discovered that in mice addicted to cocaine, in vivo low-frequency optogenetic stimulation effectively eliminated cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization by inducing depotentiation of cortical NAc inputs [92]. Specifically, optogenetic stimulation activates the metabotropic glutamate receptor protein (mGluR), which restores normal synaptic transmission and eliminates addictive behaviors by inhibiting hyperactive NAc neurons that exhibit enhanced activity in response to cocaine addiction and express D1 dopamine-receptor protein [93]. Unlike the longer-lasting effects observed with optogenetic stimulation, DBS in the NAc has only transient effects on addictive behaviors. Inspired by optogenetic research, Creed et al. modified DBS by combining low-frequency electrical stimulation with D1 dopamine receptor antagonists to simulate optogenetic mGluR-dependent synaptic transmission restoration, demonstrating a long-term capability to eliminate addictive behaviors [94].

Pharmacological stimulation

As a complement, the integration of pharmacological manipulation strategies and microfluidic technology provides various means to regulate neural behaviors related to SUDs. Microfluidics technology, often referred to as a “lab on a chip”, offers significant advantages in manipulating and analyzing diminutive fluid volumes and biological samples with remarkable precision [95]. Cho and colleagues developed a “chemical probe” that allows for the precise delivery of up to three drugs to specific brain regions while simultaneously recording electrical activity through a microelectrode array [96, 97]. In fact, the efficacy of microfluidic devices integrated with recording electrode arrays has been repeatedly demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo closed-loop neural interfaces, allowing for precise ion and drug delivery systems [98, 99]. In rodent models, the efficacy of chemical neuromodulation has been established for various substances, such as Ca2+, K+, acetylcholine, GABA, and glutamate, laying the groundwork for providing deep chemical stimulation to improve abnormal neural circuit activity in individuals with SUDs [99,100,101,102]. The integration of microfluidic technology and optogenetics offers a fascinating approach that goes beyond simple additive effects. By incorporating microfluidic conduits within penetrating optical fiber probes, in situ optogenetic transfection using viral vectors can be achieved [103]. This innovative design enables the infusion of visual proteins and subsequent optogenetic modulation in a single surgical procedure, eliminating the need for repetitive implantations that may induce damage to the brain tissue [98]. In addition, multifunctional neural probes that support drug delivery and optogenetic stimulation have paved the way for investigating the causal neural circuit mechanisms involved in addictive behaviors. A notable example of these probes is the wireless optofluidic neural probe, which enables precise control over reward-related behaviors in the NAc. By using a combination of light stimulation and selective delivery of dopamine receptor antagonists at specific sites, it allows for the initiation and blocking of location preference behavior in a highly accurate and programmable manner [104].

Overall, the feasibility of stimulation methods is crucial for the application of DBMIs systems in the treatment of SUDs. The ultimate aim of any stimulation method is to secure the United States Food and Drug Administration approval and become an affordable treatment option, thereby facilitating its dissemination to a broad spectrum of SUD patients. Consequently, it is essential to critically evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of various stimulation delivery methods, as well as their potential risks. DBS has demonstrated greater safety compared to earlier psychosurgical procedures, such as lobotomy [105], and preliminary clinical studies suggest it holds promise for the treatment of SUDs. However, DBS carries risks due to its highly invasive nature, with potential hazards such as infection [106], psychiatric disturbances [81, 106], and intracerebral hemorrhage [107], reported as complications among SUD patients. Thus, consideration should also be given to the ethical implications of such a procedure [108], and the risks and benefits of treatment must be appropriately balanced. Additionally, it is noteworthy that Mishra et al.’s examination of the Clinicaltrials.gov database revealed that one-fifth of DBS clinical trials were unsuccessful, with patient recruitment challenges, sponsor decisions, and device issues being primary reasons for the termination of studies [109]. Consequently, in future initiatives to undertake large-scale randomized controlled trials to establish the efficacy of DBS for SUDs, meticulous attention should be directed towards these significant factors. Pharmacological stimulation serves as a powerful bridge between molecular pharmacology and specific neural circuits. A challenge with pharmacological stimulation is that the drug, diffusing from the administration site, may not distribute uniformly within the targeted brain region [110]. Moreover, histological verification of cannula placement and meticulous interpretation of results in relation to the applied concentrations are crucial for drawing accurate conclusions. DBS and pharmacological stimulation exhibit non-specificity, indiscriminately affecting various types of cells within the targeted region. Optogenetic stimulation, by contrast, enables the precise activation or inhibition of targeted neuronal populations through the selective expression of opsins. The expression of opsins is typically achieved through local injection of viruses containing the opsin gene. Despite clinical trials showcasing the safety of utilizing adeno-associated viruses as carriers for gene delivery in humans, there remain significant barriers to translating laboratory research into clinical applications [111]. Similar to DBS, prolonged optical stimulation may lead to undesirable complications, including tissue overheating, photodamage, scarring, infection, and adverse immune reactions, all of which require careful examination and resolution.

Control policies

Based on the development and application of control theory, we have also proposed several potential control strategies for closed-loop DBMIs for SUDs treatment. For responsive neurostimulation in DBMIs, a prevalent control strategy employed is bang-bang control, alternatively known as “on-off” control. Upon surpassing a predetermined threshold, the DBMI system is promptly activated to initiate neurostimulation delivery, leveraging real-time measurements of oscillatory activity. Although this strategy has advantages, it is dependent on the optimal stimulus parameters determined during open-loop neurostimulation. However, if factors such as diurnal variations in neural oscillations or changes in electrode impedance render the stimulus parameters ineffective, the controller’s ability to adapt becomes limited, resulting in suboptimal performance. An alternative approach is the utilization of “dual-threshold” control, which adjusts the intensity of neurostimulation based on whether biomarker activity exceeds two predetermined thresholds. This control strategy aims to maintain biomarker activity within the desired range and has shown promising results in treating patients with Parkinson’s disease [112]. However, one drawback of this approach is its relative simplicity, as it can only modulate the intensity of neurostimulation at a fixed rate. In the proportional control strategy, the intensity of neurostimulation varies proportionally to the measured activity of biomarkers. This approach theoretically has potential for providing greater benefits than the bang-bang control and “dual-threshold” control methods because it only necessitates delivering the stimulation required for modulating biomarker activity to alleviate symptoms of SUDs.

Indeed, due to the heterogeneous nature of SUDs and individual variations, an optimal approach for adaptive control is required to achieve patient-specific or personalized treatment. Model predictive control represents an advanced strategy that can optimize output stimuli within a closed-loop system based on specific response patterns to neurostimulation [113]. However, its application in personalized SUDs treatment still requires further research and validation, as it has primarily been confined to simulation studies. Moreover, in this control model, the fine-tuning of stimulus parameters would be guided by the dynamic variations observed in biomarkers, necessitating comprehensive research to elucidate the intricate interplay through which stimuli modulate neurophysiological biomarkers closely associated with addictive behaviors. Nevertheless, it is evident that there is a paucity of relevant research in the context of closed-loop DBMIs for SUDs.

Prospects and challenges

DBMIs offer valuable insights into the neural mechanisms of addictive behaviors and new treatment approaches. The rapid advancement of sensor and stimulation technologies has provided a wide range of diverse combination options for the design of closed-loop DBMIs. Future research should focus on biomarker panels and coordinated stimulation patterns to explore closed-loop DBMIs based on multimodal biomarkers and stimulation approaches, aiming to comprehensively address the complexity of SUDs and enhance intervention effectiveness. While commercial products incorporating closed-loop DBMI technology have been developed, such as the RNS System (NeuroPace Inc.) for responsive neurostimulation and PerceptTM PC (Medtronic Inc.) for adaptive neuromodulation, the application of closed-loop DBMI technology in SUDs treatment has not been extensively explored compared to that in other neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease and depression [29, 32]. Except for the exploration conducted by Shivacharan et al. in BED [43], most studies have focused only on individual aspects such as biomarkers or neuromodulation, and investigations into application within a closed-loop framework are lacking.

Indeed, DBMIs must be approached cautiously due to ethical concerns and existing technological challenges. Applying DBMIs involve significant considerations of individual privacy and security, necessitating careful evaluation of ethical risks. Researchers must ensure that their studies adhere to ethical standards and obtain informed consent from participants. Governments should enact timely regulations to guide research boundaries and foster ethical progress in DBMI clinical studies [108]. Moreover, the primary challenge in developing neural interfaces lies in understanding optimal design practices to enhance biocompatibility, reducing initial trauma and inflammation caused by foreign body reactions while promoting device-host tissue interaction and prolonging implant performance. Progress in nanoscience, bionics, and battery technology could significantly impact DBMI. Innovative electrode designs using carbon nanotubes, anti-inflammatory coatings, or flexible materials for minimal micromotion may offer improved longevity and safety compared to traditional rigid electrodes [114]. Bionic technologies can create coatings mimicking human tissue components to reduce immune responses, scarring, and neuronal damage. High-performance, miniaturized batteries can ensure long-term DBMI functionality.

Notably, exciting progress has been made in the field of neural source activity reconstruction from subcortical structures using electroencephalography, a significant breakthrough that unlocks the potential for noninvasive deep brain recording [115,116,117]. Upconversion nanoparticles have been engineered to efficiently absorb near-infrared light that can penetrate through tissue and emit wavelength-specific visible light to stimulate deep brain neurons. This noninvasive method offers a promising avenue for optogenetic stimulation and has been empirically demonstrated to effectively induce dopamine release from genetically modified neurons in the VTA [118].

Recently, the application of focused ultrasound (FUS) to disrupt the blood-brain barrier has demonstrated initial potential as an effective therapeutic approach for non-invasive, targeted drug delivery in clinical trials addressing neurological disorders, encompassing neurodegenerative diseases and glioma [119, 120]. Moreover, there is compelling evidence indicating that FUS can function as a novel non-invasive neuromodulation modality, endowed with the ability to selectively target deep brain structures in humans with sub-millimeter precision [121, 122]. Notably, Mahoney et al. presented the report on the safe and effective low-intensity FUS neuromodulation of the bilateral NAc in patients with SUDs, leading to substantial reductions in craving both acutely and up to 90 days post-therapy [123, 124]. Despite their promise, these findings necessitate replication in randomized, sham-controlled trials with additional participants to substantiate the efficacy of FUS neuromodulation in SUDs. Heart rate variability biofeedback (HRVB) represents a novel, breathing-based, non-invasive, biobehavioral intervention. Existing studies have demonstrated that HRVB can decrease the risk of SUD relapse by diminishing cravings [125]. Recent developments in the field have led to the creation of compact, lightweight, wearable biosensors that enable users to perform HRVB while on the move [126]. In an ongoing pilot study (NCT05454657), this wearable device featuring biofeedback capabilities is being evaluated for its efficacy in treating SUDs. In addition to deep structures, certain cortical regions, such as the mPFC and ALIC mentioned in this review, are also closely associated with SUDs, suggesting potential utility for cortical interfaces in SUD treatment. Therefore, these technologies should be improved and integrated into future DBMIs to synergistically complement neuromodulation in addressing SUDs.

In summary, closed-loop DBMI technology offers new insights for SUDs treatment. Key aspects of utilizing closed-loop DBMI in SUDs therapy include reliable biomarkers, effective neuromodulation techniques, and well-designed control strategies. Exciting advancements in electrophysiological and neurochemical recordings, DBS, optogenetics, microfluidics, and control theory have propelled the field of SUDs management forward. Future research should focus on identifying optimal biomarkers for SUDs, and integrating appropriate stimulation methods with adaptive control strategies to achieve personalized patient care, thereby offering new opportunities in SUD therapy.

References

Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2022 national survey on drug use and health. 2022 NSDUH Annual National Report. 2023;PEP23-07-01-006.

Dousset C, Kajosch H, Ingels A, Schroder E, Kornreich C, Campanella S. Preventing relapse in alcohol disorder with eeg-neurofeedback as a neuromodulation technique: A review and new insights regarding its application. Addict Behav. 2020;106:106391.

Volkow ND, Blanco C. Substance use disorders: a comprehensive update of classification, epidemiology, neurobiology, clinical aspects, treatment and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2023;22:203–29.

Zhuang M, Wu Q, Wan F, Hu Y. State-of-the-art non-invasive brain–computer interface for neural rehabilitation: a review. J Neurorestoratol. 2020;8:12–25.

Shen K, Chen O, Edmunds JL, Piech DK, Maharbiz MM. Translational opportunities and challenges of invasive electrodes for neural interfaces. Nat Biomed Eng. 2023;7:424–42.

Chen D, Zhao Z, Zhang S, Chen S, Wu X, Shi J, et al. Evolving therapeutic landscape of intracerebral hemorrhage: Emerging cutting-edge advancements in surgical robots, regenerative medicine, and neurorehabilitation techniques. Transl Stroke Res. 2024. Online ahead of print

Zhao ZP, Nie C, Jiang CT, Cao SH, Tian KX, Yu S, et al. Modulating brain activity with invasive brain-computer interface: a narrative review. Brain Sci. 2023;13:134.

Rosenfeld JV, Wong YT. Neurobionics and the brain-computer interface: current applications and future horizons. Med J Aust. 2017;206:363–8.

Huang H, Bach JR, Sharma HS, Saberi H, Jeon SR, Guo X, et al. The 2022 yearbook of neurorestoratology. J Neurorestoratol. 2023;11:100054.

Yuen J, Kouzani AZ, Berk M, Tye SJ, Rusheen AE, Blaha CD, et al. Deep brain stimulation for addictive disorders-where are we now? Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19:1193–215.

Sui Y, Yu H, Zhang C, Chen Y, Jiang C, Li L. Deep brain-machine interfaces: sensing and modulating the human deep brain. Natl Sci Rev. 2022;9:nwac212.

Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:760–73.

Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–38.

Volkow ND, Morales M. The brain on drugs: from reward to addiction. Cell. 2015;162:712–25.

Naassila M. [Neurobiological bases of alcohol addiction]. Presse Med. 2018;47:554–64.

Chang R, Peng J, Chen Y, Liao H, Zhao S, Zou J, et al. Deep brain stimulation in drug addiction treatment: research progress and perspective. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:858638.

Luscher C, Malenka RC. Drug-evoked synaptic plasticity in addiction: from molecular changes to circuit remodeling. Neuron. 2011;69:650–63.

D’Souza MS. Glutamatergic transmission in drug reward: Implications for drug addiction. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:404.

Conde K, Fang S, Xu Y. Unraveling the serotonin saga: from discovery to weight regulation and beyond - a comprehensive scientific review. Cell Biosci. 2023;13:143.

Muller CP, Homberg JR. The role of serotonin in drug use and addiction. Behav Brain Res. 2015;277:146–92.

Howell LL, Cunningham KA. Serotonin 5-ht2 receptor interactions with dopamine function: implications for therapeutics in cocaine use disorder. Pharm Rev. 2015;67:176–97.

Scott SN, Garcia R, Powell GL, Doyle SM, Ruscitti B, Le T, et al. 5-ht(1b) receptor agonist attenuates cocaine self-administration after protracted abstinence and relapse in rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2021;35:1216–25.

Li Y, Simmler LD, Van Zessen R, Flakowski J, Wan JX, Deng F, et al. Synaptic mechanism underlying serotonin modulation of transition to cocaine addiction. Science. 2021;373:1252–6.

Hariz MI, Shamsgovara P, Johansson F, Hariz G, Fodstad H. Tolerance and tremor rebound following long-term chronic thalamic stimulation for parkinsonian and essential tremor. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1999;72:208–18.

Zanos S. Closed-loop neuromodulation in physiological and translational research. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2019;9:a034314.

Fisher RS, Afra P, Macken M, Minecan DN, Bagic A, Benbadis SR, et al. Automatic vagus nerve stimulation triggered by ictal tachycardia: clinical outcomes and device performance–the u.S. E-37 trial. Neuromodulation. 2016;19:188–95.

Hamilton P, Soryal I, Dhahri P, Wimalachandra W, Leat A, Hughes D, et al. Clinical outcomes of VNS therapy with aspiresr((r)) (including cardiac-based seizure detection) at a large complex epilepsy and surgery centre. Seizure 2018;58:120–6.

Russo M, Cousins MJ, Brooker C, Taylor N, Boesel T, Sullivan R, et al. Effective relief of pain and associated symptoms with closed-loop spinal cord stimulation system: preliminary results of the Avalon study. Neuromodulation. 2018;21:38–47.

Bocci T, Prenassi M, Arlotti M, Cogiamanian FM, Borellini L, Moro E, et al. Eight-hours conventional versus adaptive deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7:88.

Ferleger BI, Houston B, Thompson MC, Cooper SS, Sonnet KS, Ko AL, et al. Fully implanted adaptive deep brain stimulation in freely moving essential tremor patients. J Neural Eng. 2020;17:056026.

Cernera S, Alcantara JD, Opri E, Cagle JN, Eisinger RS, Boogaart Z, et al. Wearable sensor-driven responsive deep brain stimulation for essential tremor. Brain Stimul. 2021;14:1434–43.

Scangos KW, Khambhati AN, Daly PM, Makhoul GS, Sugrue LP, Zamanian H, et al. Closed-loop neuromodulation in an individual with treatment-resistant depression. Nat Med. 2021;27:1696–1700.

Salam MT, Perez Velazquez JL, Genov R. Seizure suppression efficacy of closed-loop versus open-loop deep brain stimulation in a rodent model of epilepsy. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2016;24:710–9.

Bina RW, Langevin JP. Closed loop deep brain stimulation for PTSD, addiction, and disorders of affective facial interpretation: Review and discussion of potential biomarkers and stimulation paradigms. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:300.

Shanechi MM. Brain-machine interfaces from motor to mood. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:1554–64.

Habelt B, Arvaneh M, Bernhardt N, Minev I. Biomarkers and neuromodulation techniques in substance use disorders. Bioelectron Med. 2020;6:4.

Giel KE, Bulik CM, Fernandez-Aranda F, Hay P, Keski-Rahkonen A, Schag K, et al. Binge eating disorder. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2022;8:16.

Udo T, Grilo CM. Psychiatric and medical correlates of dsm-5 eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52:42–50.

Schulte EM, Grilo CM, Gearhardt AN. Shared and unique mechanisms underlying binge eating disorder and addictive disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;44:125–39.

Trivedi MH, Walker R, Ling W, Dela Cruz A, Sharma G, Carmody T, et al. Bupropion and naltrexone in methamphetamine use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:140–53.

Grilo CM, Lydecker JA, Fineberg SK, Moreno JO, Ivezaj V, Gueorguieva R. Naltrexone-bupropion and behavior therapy, alone and combined, for binge-eating disorder: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179:927–37.

Schreiber LR, Odlaug BL, Grant JE. The overlap between binge eating disorder and substance use disorders: diagnosis and neurobiology. J Behav Addict. 2013;2:191–8.

Shivacharan RS, Rolle CE, Barbosa DAN, Cunningham TN, Feng A, Johnson ND, et al. Pilot study of responsive nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation for loss-of-control eating. Nat Med. 2022;28:1791–6.

Weiss NH, Kiefer R, Goncharenko S, Raudales AM, Forkus SR, Schick MR, et al. Emotion regulation and substance use: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;230:109131.

Calarco CA, Lobo MK. Depression and substance use disorders: clinical comorbidity and shared neurobiology. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2021;157:245–309.

Brenner P, Brandt L, Li G, DiBernardo A, Boden R, Reutfors J. Substance use disorders and risk for treatment resistant depression: a population-based, nested case-control study. Addiction. 2020;115:768–77.

Sheth SA, Bijanki KR, Metzger B, Allawala A, Pirtle V, Adkinson JA, et al. Deep brain stimulation for depression informed by intracranial recordings. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;92:246–51.

Mahoney JJ 3rd, Hanlon CA, Marshalek PJ, Rezai AR, Krinke L. Transcranial magnetic stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and other forms of neuromodulation for substance use disorders: Review of modalities and implications for treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2020;418:117149.

Hassan O, Phan S, Wiecks N, Joaquin C, Bondarenko V. Outcomes of deep brain stimulation surgery for substance use disorder: a systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2021;44:1967–76.

Fattahi M, Eskandari K, Sayehmiri F, Kuhn J, Haghparast A. Deep brain stimulation for opioid use disorder: a systematic review of preclinical and clinical evidence. Brain Res Bull. 2022;187:39–48.

Buzsaki G, Logothetis N, Singer W. Scaling brain size, keeping timing: evolutionary preservation of brain rhythms. Neuron. 2013;80:751–64.

Kumari LS, Kouzani AZ. Phase-dependent deep brain stimulation: a review. Brain Sci. 2021;11:414.

Cole SR, Voytek B. Brain oscillations and the importance of waveform shape. Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21:137–49.

Sayette MA. The role of craving in substance use disorders: theoretical and methodological issues. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12:407–33.

Panlilio LV, Goldberg SR. Self-administration of drugs in animals and humans as a model and an investigative tool. Addiction. 2007;102:1863–70.

Muller Ewald VA, Kim J, Farley SJ, Freeman JH, LaLumiere RT. Theta oscillations in rat infralimbic cortex are associated with the inhibition of cocaine seeking during extinction. Addict Biol. 2022;27:e13106.

Ngbokoli ML, Douton JE, Carelli RM. Prelimbic cortex and nucleus accumbens core resting state signaling dynamics as a biomarker for cocaine seeking behaviors. Addict Neurosci. 2023;7:100097.

Fattahi M, Modaberi S, Eskandari K, Haghparast A. A systematic review of the local field potential adaptations during conditioned place preference task in preclinical studies. Synapse. 2023;77:e22277.

McKendrick G, Graziane NM. Drug-induced conditioned place preference and its practical use in substance use disorder research. Front Behav Neurosci. 2020;14:582147.

Takano Y, Tanaka T, Takano H, Hironaka N. Hippocampal theta rhythm and drug-related reward-seeking behavior: an analysis of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. Brain Res. 2010;1342:94–103.

Zhu Z, Ye Z, Wang H, Hua T, Wen Q, Zhang C. Theta-gamma coupling in the prelimbic area is associated with heroin addiction. Neurosci Lett. 2019;701:26–31.

Nukitram J, Cheaha D, Kumarnsit E. Spectral power and theta-gamma coupling in the basolateral amygdala related with methamphetamine conditioned place preference in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2021;756:135939.

Samerphob N, Cheaha D, Chatpun S, Kumarnsit E. Hippocampal ca1 local field potential oscillations induced by olfactory cue of liked food. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2017;142:173–81.

Samerphob N, Cheaha D, Issuriya A, Chatpun S, Lertwittayanon W, Jensen O, et al. Changes in neural network connectivity in mice brain following exposures to palatable food. Neurosci Lett. 2020;714:134542.

Wu H, Miller KJ, Blumenfeld Z, Williams NR, Ravikumar VK, Lee KE, et al. Closing the loop on impulsivity via nucleus accumbens delta-band activity in mice and man. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:192–7.

Ge S, Geng X, Wang X, Li N, Chen L, Zhang X, et al. Oscillatory local field potentials of the nucleus accumbens and the anterior limb of the internal capsule in heroin addicts. Clin Neurophysiol. 2018;129:1242–53.

Mirza KB, Golden CT, Nikolic K, Toumazou C. Closed-loop implantable therapeutic neuromodulation systems based on neurochemical monitoring. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:808.

Rodeberg NT, Sandberg SG, Johnson JA, Phillips PE, Wightman RM. Hitchhiker’s guide to voltammetry: acute and chronic electrodes for in vivo fast-scan cyclic voltammetry. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8:221–34.

Ganesana M, Trikantzopoulos E, Maniar Y, Lee ST, Venton BJ. Development of a novel micro biosensor for in vivo monitoring of glutamate release in the brain. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019;130:103–9.

Van Gompel JJ, Chang SY, Goerss SJ, Kim IY, Kimble C, Bennet KE, et al. Development of intraoperative electrochemical detection: Wireless instantaneous neurochemical concentration sensor for deep brain stimulation feedback. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29:E6.

Lee KH, Lujan JL, Trevathan JK, Ross EK, Bartoletta JJ, Park HO, et al. Wincs harmoni: closed-loop dynamic neurochemical control of therapeutic interventions. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46675.

Li J, Liu Y, Yuan L, Zhang B, Bishop ES, Wang K, et al. A tissue-like neurotransmitter sensor for the brain and gut. Nature. 2022;606:94–101.

Xu X, Zheng C, An L, Wang R, Zhang T. Effects of dopamine and serotonin systems on modulating neural oscillations in hippocampus-prefrontal cortex pathway in rats. Brain Topogr. 2016;29:539–51.

Davidson B, Giacobbe P, George TP, Nestor SM, Rabin JS, Goubran M, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in the treatment of severe alcohol use disorder: a phase I pilot trial. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:3992–4000.

Bach P, Luderer M, Muller UJ, Jakobs M, Baldermann JC, Voges J, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in treatment-resistant alcohol use disorder: a double-blind randomized controlled multi-center trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:49.

Muller UJ, Sturm V, Voges J, Heinze HJ, Galazky I, Buntjen L, et al. Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation for alcohol addiction - safety and clinical long-term results of a pilot trial. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2016;49:170–3.

Zhang C, Li J, Li D, Sun B. Deep brain stimulation removal after successful treatment for heroin addiction. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2020;54:543–4.

Mahoney JJ, Haut MW, Hodder SL, Zheng W, Lander LR, Berry JH, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens/ventral capsule for severe and intractable opioid and benzodiazepine use disorder. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;29:210–215.

Rezai AR, Mahoney JJ, Ranjan M, Haut MW, Zheng W, Lander LR, et al. Safety and feasibility clinical trial of nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation for treatment-refractory opioid use disorder. J Neurosurg. 2024;140:231–9.

Zhu R, Zhang Y, Wang T, Wei H, Zhang C, Li D, et al. Deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens with anterior capsulotomy for drug addiction: a case report. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2020;98:345–9.

Ge S, Chen Y, Li N, Qu L, Li Y, Jing J, et al. Deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens for methamphetamine addiction: Two case reports. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:512–7.

Zhang C, Wei H, Zhang Y, Du J, Liu W, Zhan S, et al. Increased dopamine transporter levels following nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation in methamphetamine use disorder: a case report. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:1055–7.

Wang TR, Moosa S, Dallapiazza RF, Elias WJ, Lynch WJ. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of drug addiction. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;45:E11.

Goncalves-Ferreira A, do Couto FS, Rainha Campos A, Lucas Neto LP, Goncalves-Ferreira D, Teixeira J. Deep brain stimulation for refractory cocaine dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:e87–89.

Wilden JA, Qing KY, Hauser SR, McBride WJ, Irazoqui PP, Rodd ZA. Reduced ethanol consumption by alcohol-preferring (p) rats following pharmacological silencing and deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens shell. J Neurosurg. 2014;120:997–1005.

Baunez C, Dias C, Cador M, Amalric M. The subthalamic nucleus exerts opposite control on cocaine and ‘natural’ rewards. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:484–9.

Rouaud T, Lardeux S, Panayotis N, Paleressompoulle D, Cador M, Baunez C. Reducing the desire for cocaine with subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1196–1200.

Dostrovsky JO, Lozano AM. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. Mov Disord. 2002;17:S63–8.

Urbano FJ, Pagani MR, Uchitel OD. Calcium channels, neuromuscular synaptic transmission and neurological diseases. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;201-202:136–44.

Rost BR, Schneider-Warme F, Schmitz D, Hegemann P. Optogenetic tools for subcellular applications in neuroscience. Neuron. 2017;96:572–603.

Luo J, Xue N, Chen J. A review: research progress of neural probes for brain research and brain-computer interface. Biosensors (Basel). 2022;12:1167.

Pascoli V, Turiault M, Luscher C. Reversal of cocaine-evoked synaptic potentiation resets drug-induced adaptive behaviour. Nature. 2011;481:71–5.

Pascoli V, Terrier J, Espallergues J, Valjent E, O’Connor EC, Luscher C. Contrasting forms of cocaine-evoked plasticity control components of relapse. Nature. 2014;509:459–64.

Creed M, Pascoli VJ, Luscher C. Addiction therapy. Refining deep brain stimulation to emulate optogenetic treatment of synaptic pathology. Science. 2015;347:659–64.

Liu Y, Yang G, Hui Y, Ranaweera S, Zhao CX. Microfluidic nanoparticles for drug delivery. Small. 2022;18:e2106580.

Lee HJ, Son Y, Kim J, Lee CJ, Yoon ES, Cho IJ. A multichannel neural probe with embedded microfluidic channels for simultaneous in vivo neural recording and drug delivery. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1590–7.

Shin H, Lee HJ, Chae U, Kim H, Kim J, Choi N, et al. Neural probes with multi-drug delivery capability. Lab Chip. 2015;15:3730–7.

Jonsson A, Inal S, Uguz I, Williamson AJ, Kergoat L, Rivnay J, et al. Bioelectronic neural pixel: chemical stimulation and electrical sensing at the same site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:9440–5.

Proctor CM, Slezia A, Kaszas A, Ghestem A, Del Agua I, Pappa AM, et al. Electrophoretic drug delivery for seizure control. Sci Adv. 2018;4:eaau1291.

Simon DT, Kurup S, Larsson KC, Hori R, Tybrandt K, Goiny M, et al. Organic electronics for precise delivery of neurotransmitters to modulate mammalian sensory function. Nat Mater. 2009;8:742–6.

Jonsson A, Song Z, Nilsson D, Meyerson BA, Simon DT, Linderoth B, et al. Therapy using implanted organic bioelectronics. Sci Adv. 2015;1:e1500039.

Uguz I, Proctor CM, Curto VF, Pappa AM, Donahue MJ, Ferro M, et al. A microfluidic ion pump for in vivo drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2017;29:1701217.

Park S, Guo Y, Jia X, Choe HK, Grena B, Kang J, et al. One-step optogenetics with multifunctional flexible polymer fibers. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:612–9.

Jeong JW, McCall JG, Shin G, Zhang Y, Al-Hasani R, Kim M, et al. Wireless optofluidic systems for programmable in vivo pharmacology and optogenetics. Cell. 2015;162:662–74.

Caruso JP, Sheehan JP. Psychosurgery, ethics, and media: a history of Walter Freeman and the lobotomy. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;43:E6.

Leong SL, Glue P, Manning P, Vanneste S, Lim LJ, Mohan A, et al. Anterior cingulate cortex implants for alcohol addiction: a feasibility study. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17:1287–99.

Chen L, Li N, Ge S, Lozano AM, Lee DJ, Yang C, et al. Long-term results after deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens and the anterior limb of the internal capsule for preventing heroin relapse: an open-label pilot study. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:175–83.

Lo C, Mane M, Kim JH, Berk M, Sharp RR, Lee KH, et al. Treating addiction with deep brain stimulation: ethical and legal considerations. Int J Drug Policy. 2023;113:103964.

Mishra A, Begley SL, Shah HA, Santhumayor BA, Ramdhani RA, Fenoy AJ, et al. Why are clinical trials of deep brain stimulation terminated? An analysis of clinicaltrials.Gov. World Neurosurg X. 2024;23:100378.

Melonakos ED, Moody OA, Nikolaeva K, Kato R, Nehs CJ, Solt K. Manipulating neural circuits in anesthesia research. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:19–30.

Ordaz JD, Wu W, Xu XM. Optogenetics and its application in neural degeneration and regeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:1197–209.

Velisar A, Syrkin-Nikolau J, Blumenfeld Z, Trager MH, Afzal MF, Prabhakar V, et al. Dual threshold neural closed loop deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease patients. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:868–76.

Ju Z, Senlin W. A review of explicit model predictive control. In: Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st Chinese Control Conference, 25-272012, 2012.

Schouenborg J. Biocompatible multichannel electrodes for long-term neurophysiological studies and clinical therapy–novel concepts and design. Prog Brain Res. 2011;194:61–70.

Krishnaswamy P, Obregon-Henao G, Ahveninen J, Khan S, Babadi B, Iglesias JE, et al. Sparsity enables estimation of both subcortical and cortical activity from meg and eeg. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E10465–74.

Seeber M, Cantonas LM, Hoevels M, Sesia T, Visser-Vandewalle V, Michel CM. Subcortical electrophysiological activity is detectable with high-density EEG source imaging. Nat Commun. 2019;10:753.

Fahimi Hnazaee M, Wittevrongel B, Khachatryan E, Libert A, Carrette E, Dauwe I, et al. Localization of deep brain activity with scalp and subdural eeg. Neuroimage. 2020;223:117344.

Chen S, Weitemier AZ, Zeng X, He L, Wang X, Tao Y, et al. Near-infrared deep brain stimulation via upconversion nanoparticle-mediated optogenetics. Science. 2018;359:679–84.

Gorick CM, Breza VR, Nowak KM, Cheng VWT, Fisher DG, Debski AC, et al. Applications of focused ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier opening. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;191:114583.

Zhao P, Wu T, Tian Y, You J, Cui X. Recent advances of focused ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier opening for clinical applications of neurodegenerative diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2024;209:115323.

Lev-Tov L, Barbosa DAN, Ghanouni P, Halpern CH, Buch VP. Focused ultrasound for functional neurosurgery. J Neurooncol. 2022;156:17–22.

Lee K, Park TY, Lee W, Kim H. A review of functional neuromodulation in humans using low-intensity transcranial focused ultrasound. Biomed Eng Lett. 2024;14:407–38.

Mahoney JJ, Haut MW, Carpenter J, Ranjan M, Thompson-Lake DGY, Marton JL, et al. Low-intensity focused ultrasound targeting the nucleus accumbens as a potential treatment for substance use disorder: safety and feasibility clinical trial. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1211566.

Mahoney JJ 3rd, Thompson-Lake DGY, Ranjan M, Marton JL, Carpenter JS, Zheng W, et al. Low-intensity focused ultrasound targeting the bilateral nucleus accumbens as a potential treatment for substance use disorder: a first-in-human report. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;94:e41–3.

Wieman ST, Eddie D. Heart rate variability biofeedback for substance use disorder: health policy implications. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2022;9:156–63.

Chung AH, Gevirtz RN, Gharbo RS, Thiam MA, Ginsberg JPJ. Pilot study on reducing symptoms of anxiety with a heart rate variability biofeedback wearable and remote stress management coach. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2021;46:347–58.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the BioRender website (https://www.biorender.com/) for providing the drawing platform.

Funding

This work was supported by Major Program (JD) of Hubei Province (2023BAA005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92148206 and 82071330) and the Research Fund of Tongji Hospital (2022B37).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DYC: conceptualization and writing the manuscript. ZXZ, JS, SJL, XRX, ZJW, YXT, and NL: Illustration painting. WHZ, CMN, BM, JYW, JZ, and LH: critical revision of the article. ZY, PZ, and ZPT: critical revision of the article and supervising.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Wenhong Zhou is employed by Wuhan Global Sensor Technology Co., Ltd. Changmao Ni and Li Huang are employed by Wuhan Neuracom Technology Development Co., Ltd. The remaining authors disclosed no relevant relationships.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Zhao, Z., Shi, J. et al. Harnessing the sensing and stimulation function of deep brain-machine interfaces: a new dawn for overcoming substance use disorders. Transl Psychiatry 14, 440 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-024-03156-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-024-03156-8

This article is cited by

-

Common neural patterns of substance use disorder: a seed-based resting-state functional connectivity meta-analysis

Translational Psychiatry (2025)