Abstract

Predicting disease trajectories in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) can allow designing personalized therapeutic strategies. In this study, we aimed to show that measuring patients’ plasticity – that is the susceptibility to modify the mental state – identifies at baseline who will recover, anticipating the time to transition to wellbeing. We conducted a secondary analysis in two randomized clinical trials, STAR*D and CO-MED. Symptom severity was assessed using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology while the context was measured at enrollment with the Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire. Patients were retrospectively grouped based on both their time to response or remission and their plasticity levels at baseline assessed through a network-based mathematical approach that operationalizes plasticity as the inverse of the symptom network connectivity strength. The results show that plasticity levels at baseline anticipate time to response and time to remission. Connectivity strength among symptoms is significantly lower – and thus plasticity higher – in patients experiencing a fast recovery. When the interplay between plasticity and context is considered, plasticity levels are predictive of disease trajectories only in subjects experiencing a favorable context, confirming that plasticity magnifies the influence of the context on mood. In conclusion, the assessment of plasticity levels at baseline holds promise for predicting MDD trajectories, potentially informing the design of personalized treatments and interventions. The combination of high plasticity and the experience of a favorable context emerges as critical to achieve recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plasticity, defined as the ability to modify brain functioning and behavior, is increasingly acknowledged as a pivotal process in psychiatry and applied neuroscience as it plays a fundamental role in the reorganization of the neural and mental processes during the transition from psychopathology to well-being [1, 2]. Nonetheless, elevated plasticity levels, which make the brain, and consequently behavior and mental state, more susceptible to change, do not inherently result in a clinical improvement, which instead arises from the interplay between an individual’s plasticity and quality of life [3, 4]. Indeed, an enhancement of plasticity has been demonstrated to be therapeutically effective when associated with favorable contextual factors [5,6,7,8,9].

The identification of relevant predictors of the duration of a depressive episode provides prognostic indicators that can be used for optimizing personalized treatments [10]. Without an effective prediction of disease trajectories, treatments might be prematurely ended or altered while they could still be clinically significant, potentially resulting in patient’s loss of compliance or dropout. Previous studies have identified potential predictors, such as clinical, psychological, and biological measures as well as neuroimaging data, which exhibit reasonable discriminative ability in predicting disease trajectories [11,12,13,14,15]. However, a theoretical framework accounting for their predictive power is still lacking and their time resolution needs improvement for an effective application in clinical settings.

The network theory of plasticity has recently introduced an operationalization of plasticity [1, 16] wherein the inverse of connectivity strength of a network of behavioral elements, such as symptoms, is a measure of plasticity and, thus, of the individual’s susceptibility to change [17]. The present study was aimed to demonstrate the validity of such operationalization to predict clinical trajectories and, in particular, the time to transition from psychopathology to wellbeing. To this aim, we conducted a network analysis using data from two randomized clinical trials involving outpatients with major depressive disorder (MDD), the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) and Combining Medications to Enhance Depression outcomes (CO-MED) studies. We expected that the assessment of connectivity strength at baseline, being a measure of plasticity, enables anticipating the time to recover from MDD. More in detail, the weaker the connectivity – and thus the higher the plasticity – the shorter the time to improvement. In addition, since plasticity magnifies the influence of contextual factors, we expected network connectivity to be highly reliable in predicting time to recovery in patients experiencing a favorable quality of life.

Materials and methods

Overall design

We conducted a secondary analysis on two datasets: the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00021528) and the Combining Medications to Enhance Depression outcomes (CO-MED) study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00590863). Both the studies are randomized clinical trials of outpatients with major depressive disorder (MDD) aimed at comparing the efficacy of different treatment options. The studies received ethical approval and participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

The STAR*D enrolled a total of 4041 outpatients (18–75 years old) with nonpsychotic MDD (17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HAM-17] score ≥ 14). Patients were excluded when pregnant or breast-feeding, with a primary diagnosis of bipolar, psychotic, obsessive-compulsive, or eating disorders, with general medical conditions contraindicating the use of protocol medications, with substance dependence, or with a clear history of nonresponse or intolerance. In the present study, we considered only the first stage of the clinical trial, defined as Level 1 (see https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28). The STAR*D protocol involved clinical visits at 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12 weeks. The CO-MED study enrolled 665 outpatients (18–75 years old) with MDD (HAM-17 score ≥ 16). Patients with psychosis, bipolar disorder and those in need of hospitalization were ineligible (see http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00590863). The main results of the present work are based on STAR*D, while the CO-MED study was used for confirmatory results.

Symptoms of major depressive disorder

Both in the STAR*D and the CO-MED, MDD symptom severity was assessed at enrollment and each clinical visit over the weeks using the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician-Rating scale (QIDS-C16). The QIDS-C16 consists of 16 items measuring the nine criterion symptom domains that define MDD according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV). The scores for three domains – sleep, appetite/weight, and restlessness/agitation – are based upon the maximum score of two or more questions, while each of the remaining domains is rated by a single item. All domains are scored from 0 (i.e., no problem) to 3 points (i.e., severe problem). The overall total score is calculated by summing the scores of all domains and it ranges from 0 (i.e., not depressed) to 27 (i.e., most depressed). The HAM-17 rating scale was used to assess the severity of depression at enrollment and at the end of the study.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest in this study was the treatment response defined as a reduction of at least 50% of baseline QIDS-C16 score, measured at each visit (i.e., 4, 6, 9, 12). The secondary outcome was the achievement of remission, defined by a score of ≤5 on the QIDS-C16. The sample was stratified into independent groups based on the time of response achievement measured at weeks 4, 6, 9, and 12. A parallel stratification was conducted for remission achievement.

Subjective appraisal and quality of life

The Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-short form (Q-LES-Q-SF) was employed to evaluate the baseline quality of life among the patients. The Q-LES-Q-SF is a self-reported questionnaire, with 16 items, derived from the general activities scale of the original 93-item form. The questionnaire is adopted in clinical practice to measure the degree of enjoyment and satisfaction experienced by patients in various areas of their daily life (e.g., family, work, and daily activity). Each item is scored on a scale from 1 (i.e., very poor) to 5 points (i.e., very good). Two of the 16 items refer to general aspects of life and are not included in the calculation of the overall total score, which thus ranges from 14 (i.e., very poor) to 70 (i.e., very good). Based on the patients’ Q-LES-Q-SF total score distribution, we set a cut-off point at the 40th percentile (Q-LES-Q-SF score ≤ 41) to identify patients experiencing a Poor context and a cut-off point at the 60th percentile (Q-LES-Q-SF score ≥ 48) for patients experiencing a Good context. Subsequently, to ensure the inclusion of all patients, including those experiencing a context of neither good nor poor but mid-quality, we conducted a further set of analyses, where we set a cut-off point at the 60th percentile to identify patients experiencing a Good context as those above this threshold, and patients experiencing a Mid-Poor context as those below it. Since the group of responders at week 12 had low sample size (n = 78) and it was not possible to split it into two sub-groups based on the Q-LES-Q-SF score, the analysis concerning the effect of the subjective context was limited to week 9. Therefore, in the plasticity by context analysis, patients who did not respond by week 9 were grouped as non-responders by week 9. Unfortunately, the limited samples size of patients showing remission at the different timepoints did not allow to run the analysis concerning the effect of subjective context.

Statistical analysis

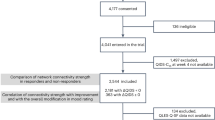

All statistical analyses have been performed on R version 4.2.2. No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. The sample sizes used in the analyses are detailed in Fig. S1, Fig. S2 and Fig. S7 for the STAR*D and in Fig. S3 for the CO-MED.

Network generation

To generate the networks, we used the estimate Network function in the bootnet (Version: 1.5.6) R package. The undirected weighted networks with 9 nodes were generated by using partial correlations among the depressive symptoms assessed with the QIDS-C16. We exploited the Gaussian Graphical Model, and we estimated the covariance matrix using Spearman’s Rank correlation [18]. The correlation networks have been generated without regularization.

Differences in global network connectivity strength

Networks were compared based on global network connectivity strength – defined as the sum of the magnitude of the weighted connections – using the NTC function in the Network Comparison Test (Version: 2.2.2) R package. The Network Comparison Test (NTC) is a permutation-based test that randomly regroups participants from the network repeatedly [19, 20]. The resulting distribution under the null hypothesis (i.e., assuming both groups are equal) was used to test the observed difference between the networks (i.e., whether the observed statistics falls within the 95th percentile for a significance level of 0.05). Networks were compared using 1000 random permutations, which is the number of permutations to obtain reliable results. We compared the global network connectivity strength at baseline.

Reporting standards for psychological network analyses in cross-sectional data

The methods implemented in the present study follow the reporting guidelines of the EQUATOR network for psychological network analyses in cross-sectional data [21].

Results

Connectivity at baseline is related to the time needed to achieve the response

Patients constituting the evaluable sample (n = 995, Fig. S1) were divided into four independent groups according to the timing of achieving response (reduction of at least 50% of the Quick 16-Item Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology [QIDS-C16] score compared with the baseline, Fig. S2): (i) week 4 (n = 353), (ii) week 6 (n = 236), (iii) week 9 (n = 158), and (iv) week 12 (n = 78). The groups did not differ in terms of severity of depressive symptoms at baseline (Tab. S1) measured with the QIDS-C16 (Kruskal-Wallis chi squared = 1.39, p = 0.706) and 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D 17; Kruskal-Wallis chi squared = 0.40, p = 0.940). The symptom connectivity strength computed at the baseline showed a proportional relationship with the time required to achieve the response, with connectivity values gradually increasing from 2.82 to 5.49 across weeks 4 to 12 (Fig. 1). We employed a network comparison test (NTC) to evaluate connectivity strength across pair-networks, revealing significant differences between patients who responded at weeks 4, 6, and 9 compared to those at week 12. This observation was consistent since the results were replicated using the CO-MED dataset (Tab. S2, Figs. S3A and S4A). Remarkably, the proportional relationship between symptom connectivity and recovery time was further validated through a correlation analysis [Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) = 0.92, p = 0.083, Fig. 2A], reinforcing the association between baseline connectivity strength and time to response. These results were corroborated by replicating the analysis using the CO-MED dataset (r = 0.94, p = 0.060, Fig. S5A). Additionally, we explored network connectivity strength over time and observed that, across all patient groups, it showed a trend toward a decrease prior to achieving clinical response, except for the group that responded in week 4, which consistently exhibited weak connectivity (Figure S6). This decrease was correlated to connectivity strength at baseline (r = 0.89, p = 0.111) and reached statistical significance in the group with the highest baseline connectivity strength (baseline vs. week 12, p = 0.009), which responded as latest.

Network structures of the responder groups at different weeks. Blue connections represent positive associations, whereas red connections represent negative associations. Thicker edges represent stronger associations (both for positive and negative). 1 - sleeping problem (sleep onset insomnia, mid, early and hypersomnia); 2 - depressed mood; 3 - weight/appetite change; 4 - concentration/decision making; 5 - outlook (self); 6 - suicidal ideation; 7 - involvement; 8 - energy/fatigability; 9 - psychomotor agitation. Network comparison test (NCT) was used to compare groups. *p < 0.05. In detail, responders at week 4 vs. week 12: p = 0.014; responders at week 6 vs. week 12: p = 0.031; responders at week 9 vs. week 12: p = 0.021.

A two-sided Pearson’s correlation test was conducted to evaluate the relationship between baseline connectivity strength and the achievement of (A) response and (B) remission. The dots represent groups of patients who achieved response (A) and remission (B) at week 4, 6 9 and 12. r - Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Connectivity at baseline is related to the time needed to achieve remission

We extended our analysis to examine the symptom connectivity strength at baseline relative to the time to achieve remission, defined as a QIDS-C16 score of ≤5. The original sample was divided into four independent groups based on the remission timing (Fig. S7): (i) week 4 (n = 176), (ii) week 6 (n = 149), (iii) week 9 (n = 153), and (iv) week 12 (n = 136). Our analysis revealed a consistent proportional relationship between symptom connectivity strength and the time required to achieve remission with connectivity values gradually increasing from 2.85 to 4.04 across weeks 4 to 12 (Fig. 3). The network comparison test showed significant differences between remitters at week 4 and week 6 compared to those achieving remission at week 12. Moreover, baseline connectivity was positively correlated with the time needed to achieve remission (r = 0.99, p = 0.008, Fig. 2B). Once more, the results were replicated by the analysis on the CO-MED dataset, wherein we confirmed a positive correlation between connectivity strength at baseline and time to remission (r = 0.99, p = 0.008, Fig. S5B). The overlap between the results on response and remission suggests a general proportional association between baseline connectivity strength and time to recovery. However, in the case of remission, patients’ groups differed in terms of severity of depressive symptoms at baseline (see Table S1 for the STAR*D dataset and Table S2 for the CO-MED dataset).

Network structures of the remitted groups at different weeks. Blue connections represent positive associations, whereas red connections represent negative associations. Thicker edges represent stronger associations (both for positive and negative). 1 - sleeping problem (sleep onset insomnia, mid, early and hypersomnia); 2 - depressed mood; 3 - weight/appetite change; 4 - concentration/decision making; 5 - outlook (self); 6 - suicidal ideation; 7 - involvement; 8 - energy/fatigability; 9 - psychomotor agitation. Network comparison test (NCT) was used to compare groups. *p < 0.05. In detail, responders at week 4 vs. week 12: p = 0.021; responders at week 6 vs. week 12: p = 0.037.

The interplay between context and plasticity

We delved deeper into the role of plasticity in determining the time to achieve recovery by exploring its relationship with context. Context was assessed with the Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-short form (Q-LESQ-SF) scale that measures the patients’ satisfaction and life enjoyment. We defined patients experiencing the Good or the Poor context as those scoring below the 40th percentile and above the 60th percentile, respectively, on the Q-LESQ-SF scale. We thus grouped patients according to their context quality and the week in which they achieved the response (Fig. 4A). Among patients achieving response by week 4, those experiencing a good quality of context exhibited significantly lower baseline network connectivity compared to those experiencing a poor quality of context (p = 0.01), demonstrating that a rapid improvement in favorable conditions is associated with low connectivity strength and thus high plasticity (Fig. 4A). The relevance of a good quality of life context to achieve the response in patients with high plasticity is further corroborated by the strong and significant correlation between plasticity levels and time to response in patients experiencing favorable conditions (r = 0.99, p = 0.008). Accordingly, connectivity strength was significantly higher in patients who did not show response compared with responders at week 4 (p = 0.009) and responders at week 6 (p = 0.021). Such correlation is lacking in patients experiencing a poor quality of context (r = −0.52, p = 0.480), indicating that, when conditions are not favorable, the recovery process is not associated to plasticity. We then considered all patients, including those experiencing a context of neither good nor poor but mid-quality, and investigated whether it was possible to identify differences at baseline between responders and non-responders in the light of the interplay of plasticity and context quality. In this case, we set the cutoff at the 60th percentile on the Q-LESQ-SF scale, with patients experiencing Good context above this threshold and those experiencing Mid-Poor context below it (Fig. 4B). In the group of non-responders, patients experiencing a Mid-Poor quality of context exhibited lower connectivity strength (i.e., higher plasticity) compared to those experiencing a Good quality of context (p = 0.012), confirming that high plasticity in unfavorable or neutral conditions does not lead to recovery. Additionally, within those patients experiencing a Good context, non-responders exhibited higher connectivity compared to responders (p = 0.036), suggesting that favorable contextual conditions are beneficial only patients with high plasticity (i.e., low connectivity strength). When investigating connectivity strength in all patients according to context quality and the week of response achievement, we observed results overlapping with those described for the Poor and Good context groups only. However, in the latter case, differences were less pronounced (Fig. S8). The fact that the larger the difference in context quality, the larger the impact, supports the pivotal role played by context. It is worth noting that the results of the plasticity by context interplay were not biased by differences at baseline in severity as groups experiencing the same context but achieving response at different timepoints did not differ (Table S3 and Table S4). As expected, an overall difference in severity was found between patients experiencing a Good vs. a Poor or Mid-Poor environment.

A. Connectivity strength at baseline in patients grouped according to their context quality and the week in which they achieved the response. Patients were defined as experiencing the Good and the Poor context as those scoring below the 40th percentile and above the 60th percentile, respectively, on the Q-LESQ-SF scale. B. Comparison of connectivity strength between all patients grouped according to their context quality and whether they achieved the response by week 9. Patients were defined as experiencing a Good and Mid-Poor context as those scoring below and above the 60th percentile, respectively, on the Q-LESQ-SF scale. *p < 0.05, **p = 0.01. $$ p = 0.009, $ p = 0.021, vs. No-response by week 9 experiencing a Good context.

Discussion

The present results show that, at baseline, connectivity strength among symptoms is a reliable measure of plasticity, and thus, a predictor of disease trajectory, as it correlates with both time to response and time to remission in patients with MDD. The lower the connectivity, the higher the plasticity and, thus, the shorter the time of transition to wellbeing. Furthermore, we highlight the pivotal role of the interplay between plasticity and context, as the relationship between connectivity strength and time to recovery is highly significant in favorable but not in unfavorable conditions: the experience of a good life context appears to promote mental wellbeing only when combined with high plasticity.

In previous studies, we have proposed the network-based operationalization of plasticity [16], showing that the weaker the connectivity of the symptom network, the higher the plasticity, and the greater the ability to change mood rating according to contextual factors [17]. Here, we have further proved the validity of such operationalization, illustrating its reliability in predicting the time to recovery according to plasticity levels and context, as well as showing that achieving clinical response requires a reduction in connectivity.

Such a dynamic perspective holds potential key implications for clinical practice. First, plasticity levels can anticipate the time to recovery. While plasticity, or flexibility, is known to affect the speed of adaptation or learning in disciplines from ecology to neuroscience [22, 23], the effects of different plasticity levels on the time required for the transition to wellbeing have been limitedly explored in the mental health field. For instance, differences in plasticity levels due to the serotonin-transporter-linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR) have been associated to different temporal trajectories. Individuals carrying the allele associated with higher plasticity develop depression more rapidly when exposed to stressful conditions. However, they also exhibit faster recovery when contextual conditions improve [24], corroborating the view that the higher the plasticity, the shorter the time to transition from psychopathology to wellbeing.

Another implication emerging from the perspective here proposed is that the beneficial therapeutic effects of experiencing a good quality of life are expected to manifest only in patients with enhanced plasticity, in line with the view that plasticity magnifies the impact of context on mood [3, 4]. Indeed, we have shown a very strong correlation between plasticity levels and time to response in patients experiencing a favorable context, which disappears in unfavorable conditions. Moreover, we have shown that low plasticity can jeopardize recovery in individuals experiencing good context, as non-responders experiencing favorable conditions have low plasticity levels. It is noteworthy that reduced plasticity might prove beneficial in unfavorable conditions, making patients less sensitive to contextual factors. Indeed, we found that patients who rapidly achieve the response despite the experience of a poor quality of life, exhibit high connectivity strength and thus low plasticity. These results confirm the differential role of plasticity levels in promoting wellbeing according to contextual influences [3, 4, 25]. When translating these findings into clinical practice, it appears crucial to integrate strategies capable to improve the patients’ living conditions, such as environmental or lifestyle interventions [26, 27], or patients’ subjective appraisal, such as psychotherapeutic approaches [28], with treatments that enhance plasticity. This approach is likely to maximize therapeutic effectiveness. Consistent with this viewpoint, combining plasticity-enhancing drugs, such as psychedelics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, with psychotherapy has been shown to be more effective than either approach alone [25].

A further potential clinical implication of the operationalization of plasticity is the development of novel and personalized therapeutic strategies based on stratifying patients according to their plasticity levels and living context. Patients exhibiting high plasticity are expected to show a rapid recovery if they undergo psychotherapy, environmental interventions, or other therapies aimed at improving their quality of life. By contrast, patients with low plasticity are expected to show slower transition to wellbeing that might be accelerated by enhancing-plasticity treatments [1, 3, 6]. The availability of information about plasticity levels at baseline enables to identify patients’ most likely disease trajectories throughout therapy, and therefore inform patients’ and clinicians’ expectations and decisions.

The strengths of this study include the replication of the results across different measures (i.e., response and remission) and two independent clinical datasets, the STAR*D and the CO-MED. The limitations include the lack of placebo controls, as all the patients received antidepressant drugs. In addition, treatments varied across patients for dosages (in both STAR*D and CO-MED) and compounds (in CO-MED) and a statistical analysis of the relationship between connectivity strength and temporal trajectories according to different treatment regimens could not be performed due to the limited sample size. This, however, does not imply that treatment regimen is not important [14]. Moreover, the preset results are based on network analyses conducted solely at the group level because multiple baseline symptom assessments for individual patients were not available. Thus, further investigations into the association between connectivity strength and plasticity at the individual level are warranted. Another limitation of our analysis is that it focused on patients showing improvements in mental health. Due to the limited number of patients with worsening symptoms, we were unable to assess whether the operationalization of plasticity applies to them as well. Thus, this issue still needs to be addressed. Finally, though our results may raise awareness about potential factors and mechanisms affecting treatment efficacy, they do not justify withholding medication without professional advice for any reason. The insights gained from this study are intended to inform further research, not to serve as a directive for immediate changes in clinical practice. Any adjustments to medication regimens should only be made under the supervision of qualified healthcare professionals, who are equipped to consider the all relevant clinical factors, patient history, and individual circumstances.

The development of strategies to anticipate critical transitions, such as the one from psychopathology to wellbeing, is an emerging field in psychiatry and other disciplines [29, 30]. Based on systems science [31, 32], specific signals, such as critical slowing down, may indicate how close a system is to transition. This includes how an individual is progressing towards the onset of depression or to the achievement of wellbeing [33]. The operationalization of plasticity proposed here is an additional and complementary approach that holds the promise to further advance the capability to anticipate the time of transitioning to wellbeing and thus to predict disease trajectories. This information may prove particularly valuable to develop personalized therapeutic strategies based on patient’s plasticity and contextual factors that hold the potential to reduce the burden of mental illness not only at clinical, but also at societal and economic levels [11, 34]. Indeed, in the light of the assessment of plasticity, the context provides key information that conveys relevant clinical utility, warranting its evaluation for an accurate prognosis [35, 36]. Finally, these findings offer a potential explanation for why only some individuals benefit from favorable contextual factors, despite the growing recognition of these factors as key in promoting wellbeing [37, 38].

Data availability

The two datasets utilized in this study are accessible via the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Data Archive. Both the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) and Combining Medications to Enhance Depression Outcomes (CO-MED) datasets can be obtained through a formal request to NIMH, accessible at https://nda.nih.gov/.

Code availability

R codes used for the analyses are publicly available and can be downloaded at the following link: https://figshare.com/s/122ea89d6294e8ab2730.

Change history

22 April 2025

This research was supported by ERA-NET Neuron, Neurobiological mechanisms of the environment- plasticity - behaviour interaction (EnviroMood) and by the grant from the Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Finalizzata, RF-2018-12367249.

References

Branchi I. Plasticity in mental health: a network theory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;138:104691.

Price RB, Duman R. Neuroplasticity in cognitive and psychological mechanisms of depression: an integrative model. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:530–43.

Branchi I. The double edged sword of neural plasticity: increasing serotonin levels leads to both greater vulnerability to depression and improved capacity to recover. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:339–51.

Belsky J, Jonassaint C, Pluess M, Stanton M, Brummett B, Williams R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes? Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:746–54.

Bottemanne H, Morlaas O, Claret A, Sharot T, Fossati P, Schmidt L. Evaluation of early ketamine effects on belief-updating biases in patients with treatment-resistant depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:1124–32.

Carhart-Harris RL, Roseman L, Haijen E, Erritzoe D, Watts R, Branchi I, et al. Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32:725–31.

Chiarotti F, Viglione A, Giuliani A, Branchi I. Citalopram amplifies the influence of living conditions on mood in depressed patients enrolled in the STAR*D study. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1066.

Klobl M, Seiger R, Vanicek T, Handschuh P, Reed MB, Spurny-Dworak B, et al. Escitalopram modulates learning content-specific neuroplasticity of functional brain networks. Neuroimage. 2022;247:118829.

Viglione A, Chiarotti F, Poggini S, Giuliani A, Branchi I. Predicting antidepressant treatment outcome based on socioeconomic status and citalopram dose. Pharmacogenomics J. 2019;19:538–46.

Kohler S, Chrysanthou S, Guhn A, Sterzer P. Differences between chronic and nonchronic depression: systematic review and implications for treatment. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36:18–30.

Skelton M, Carr E, Buckman JEJ, Davies MR, Goldsmith KA, Hirsch CR, et al. Trajectories of depression and anxiety symptom severity during psychological therapy for common mental health problems. Psychol Med. 2023;53:6183–93.

Delgadillo J, de Jong K, Lucock M, Lutz W, Rubel J, Gilbody S, et al. Feedback-informed treatment versus usual psychological treatment for depression and anxiety: a multisite, open-label, cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:564–72.

Frassle S, Marquand AF, Schmaal L, Dinga R, Veltman DJ, van der Wee NJA, et al. Predicting individual clinical trajectories of depression with generative embedding. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102213.

Penninx BW, Nolen WA, Lamers F, Zitman FG, Smit JH, Spinhoven P, et al. Two-year course of depressive and anxiety disorders: results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Affect Disord. 2011;133:76–85.

Buckman JEJ, Cohen ZD, O’Driscoll C, Fried EI, Saunders R, Ambler G, et al. Predicting prognosis for adults with depression using individual symptom data: a comparison of modelling approaches. Psychol Med. 2023;53:408–18.

Branchi I. A mathematical formula of plasticity: measuring susceptibility to change in mental health and data science. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2023;152:105272.

Delli Colli C, Chiarotti F, Campolongo P, Giuliani A, Branchi I. Towards a network-based operationalization of plasticity for predicting the transition from depression to mental health. Nat Ment Health. 2024;2:200–8.

Isvoranu AM, Epskamp S. Which estimation method to choose in network psychometrics? Deriving guidelines for applied researchers. Psychol Methods. 2023;28:925–46.

van Borkulo CD, van Bork R, Boschloo L, Kossakowski JJ, Tio P, Schoevers RA, et al. Comparing network structures on three aspects: a permutation test. Psychol Methods. 2023;28:1273–85.

van Borkulo C, Boschloo L, Borsboom D, Penninx BW, Waldorp LJ, Schoevers RA. Association of symptom network structure with the course of [corrected] depression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1219–26.

Burger J, Isvoranu AM, Lunansky G, Haslbeck JMB, Epskamp S, Hoekstra RHA, et al. Reporting standards for psychological network analyses in cross-sectional data. Psychol Methods. 2023;28:806–24.

van Schaik CP. The costs and benefits of flexibility as an expression of behavioural plasticity: a primate perspective. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20120339.

Kasada M, Yoshida T. The timescale of environmental fluctuations determines the competitive advantages of phenotypic plasticity and rapid evolution. Popul Ecol. 2020;62:385–94.

Delli Colli C, Borgi M, Poggini S, Chiarotti F, Cirulli F, Penninx B, et al. Time moderates the interplay between 5-HTTLPR and stress on depression risk: gene x environment interaction as a dynamic process. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:274.

Grunder G, Brand M, Mertens LJ, Jungaberle H, Kartner L, Scharf DJ, et al. Treatment with psychedelics is psychotherapy: beyond reductionism. Lancet Psychiatry. 2024;11:231–6.

Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013:CD004366.

Borgi M, Marcolin M, Tomasin P, Correale C, Venerosi A, Grizzo A, et al. Nature-based interventions for mental health care: social network analysis as a tool to map social farms and their response to social inclusion and community engagement. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2019;16:3501.

Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Ciharova M, Miguel C, Noma H, Furukawa TA. The effects of psychotherapies for depression on response, remission, reliable change, and deterioration: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144:288–99.

Scheffer M, Carpenter SR, Lenton TM, Bascompte J, Brock W, Dakos V, et al. Anticipating critical transitions. Science. 2012;338:344–8.

Scheffer M, Carpenter S, Foley JA, Folke C, Walker B. Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature. 2001;413:591–6.

Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:5–13.

Scheffer M, Bockting CL, Borsboom D, Cools R, Delecroix C, Hartmann JA, et al. A dynamical systems view of psychiatric disorders-theory: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:618–23.

van de Leemput IA, Wichers M, Cramer AO, Borsboom D, Tuerlinckx F, Kuppens P, et al. Critical slowing down as early warning for the onset and termination of depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:87–92.

Lundberg J, Cars T, Loov SA, Soderling J, Sundstrom J, Tiihonen J, et al. Association of treatment-resistant depression with patient outcomes and health care resource utilization in a Population-Wide Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80:167–75.

Kendler KS, Myers J, Halberstadt LJ. Should the diagnosis of major depression be made independent of or dependent upon the psychosocial context? Psychological Med. 2010;40:771–80.

Patten SB. Letter to the Editor: context dependency of major depression. Psychological Med. 2010;40:1757–8.

Branchi I. Uncovering the determinants of brain functioning, behavior and their interplay in the light of context. Eur J Neurosci. 2024;60:4687–706.

Kendler KS, Woodward J. Top-down causation in psychiatric disorders: a clinical-philosophical inquiry. Psychol Med. 2021;51:1783–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stella Falsini (Istituto Superiore di Sanità) for editorial support.

Funding

This research was supported by ERA-NET Neuron, Neurobiological mechanisms of the environment- plasticity - behaviour interaction (EnviroMood) and by the grant from the Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Finalizzata, RF-2018-12367249.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IB conceptualized the theoretical background underpinning the study and wrote the manuscript in collaboration with CDC and AV. CDC wrote the R codes and supervised the analyses in consultation with AV, FC, AG and IB. Review and editing: SP, FC. All authors of this study have fulfilled the criteria for authorship required by Nature Portfolio journals as their participation was essential for the design and implementation of the study. Roles and responsibilities were agreed among authors. All authors have agreed to all manuscript contents.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The Italian Ministry of Health and the Istituto Superiore di Sanità had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00021528) and the Combining Medications to Enhance Depression outcomes (CO-MED) study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00590863) analyzed in the present paper received ethical approval and enrolled participants provided written informed consent. In addition, we confirmed that all methods were performed in accordance with current guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delli Colli, C., Viglione, A., Poggini, S. et al. A network-based analysis anticipates time to recovery from major depression revealing a plasticity by context interplay. Transl Psychiatry 15, 32 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03246-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03246-1