Abstract

There is emerging evidence that diet plays a key contributor to brain health, however, limited studies focused on the association of dietary inflammatory potential with brain disorders. This study aimed to examine the association of dietary inflammation with brain disorders in the UK biobank. The prospective cohort study used data from 2006 to 2010 from the UK Biobank, with the median follow-up duration for different outcomes ranging between 11.37 to 11.38. Dietary inflammatory index and Energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index [DII and EDII] were assessed through plausible dietary recalls. Outcomes included brain disorders (all-cause dementia [ACD], Alzheimer’s disease [AD], Parkinson’s disease [PD], stroke, sleep disorder, anxiety and depression disorder) and brain magnetic resonance imaging measures. Cox proportional-hazard models, restricted cubic spline model [RCS], Ordinary least squares regressions, and structural equation models were used to estimate associations. Of 164,863 participants with available and plausible dietary recalls, 87,761 (53.2%) were female, the mean (SD) age was 58.97 (8.05) years, and the mean (SD) education years was 7.49 (2.97) years. Vegetables and fresh fruits show significant anti-inflammatory properties, while low-fiber bread and animal fats show pro-inflammatory properties. The nonlinear associations of DII and EDII scores with ACD, AD, sleep disorder, stroke, anxiety, and depression were observed. Multivariable-adjusted HRs for participants in highest DII score VS lowest DII score were 1.165 (95% CI 1.038–1.307) for ACD, 1.172 (95% CI 1.064–1.291) for sleep disorder, 1.110 (95% CI 1.029–1.197) for stroke, 1.184 (95% CI 1.111–1.261) for anxiety, and 1.136 (95% CI 1.057–1.221) for depression. Similar results were observed with regard to EDII score. Compared with the lowest EDII score group, the highest group showed a higher risk of anxiety, depression, sleep disorder, stroke and dementia. Results from sensitivity analyses and multivariable analyses were similar to the main results. Pro-inflammatory diets were associated with a higher risk of brain disorders. Our findings suggest a potential means of diet to lower risk of anxiety, depression, sleep disorder, stroke, and dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With an increase in the aging population worldwide, brain disorders, the disturbance of brain health characterized by structural damage or/and functional impairment in the brain, are being increasingly recognized as the leading cause of disabilities and death [1, 2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the incidence and prevalence of brain diseases account for one-third of all diseases in developed countries [2]. Primordial prevention (i.e., the prevention of risk factor onset) is increasingly recognized as a complementary strategy for the prevention of brain disorders [3].

Inflammation has been widely suggested as a contributor to aging and brain disorders, such as depression, anxiety disorders, and dementia [4,5,6]. Diet has been identified as a strong preventive measure. Substantial evidence suggested that diet, including foods, nutrients, and non-nutrient food components can modulate inflammation status [7, 8]. The dietary inflammatory index [DII], which provides the base for new lines of investigation of dietary pattern and human health, is correlated with select inflammatory markers, including IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and CRP, and consists of the intake of various parameters [9]. The Energy-adjusted Dietary Inflammatory Indes [EDII] score calculated based on DII score and adjusting for energy expenditures per 1000 kcal. The advantage of the EDII over the original DII is that it accounts for inter-individual differences in energy intake [10]. So far, there have been a number of studies on the impact of DII on myocardial infarction [11], diabetic mellitus [12], and mortality [13]. However, a limited number of studies have examined the role of inflammatory diet in the acquisition of brain disorders.

Therefore, using data on reported measures of dietary habits from the UK biobank cohort, we derived dietary scores for DII and EDII and conducted a large prospective cohort study to identify the associations between DII and EDII scores and the risk for brain disorders, explore the potential mechanisms contributing to the associations (Fig. 1 and sFig. 1).

Left, the data used in the study from UK Biobank including dietary assessments, brain disorders, and inflammation. Top right, associations of DII and EDII scores with brain disorders. Bottom right, potential mechanisms contributing to the associations of dietary inflammatory potential with brain disorders. Abbreviations: DII Dietary inflammatory index, EDII Energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index, DTI Diffusion tensor imaging, CI Confidence interval.

Methods

Participants

Individuals from UKB were included in the present study. The UKB is a national prospective cohort enrolling participants aged 40–69 years from 22 assessment centers across England, Scotland, and Wales between 2006 and 2010 [14, 15]. The database is linked to national health datasets, including primary care, hospital inpatient, death, and cancer registration data. All study participants provided written informed consent. This study utilized the UK Biobank Resource under application number 19,542. Dietary under-reporters (Energy intake: Estimated energy requirements [EI: EER] <95% CI EI: EER) and over-reporter (EI: EER >95% CI EI: EER) were excluded in the current study [16].

Dietary inflammatory index

Individuals’ DII scores were estimated by using the dietary intake data from WebQ [17] (sMethods 1) to measure their dietary inflammatory potential, with a higher score indicating a pro-inflammatory diet and a lower score indicating an anti-inflammatory diet. Participants’ exposure to each food parameter was expressed as a Z score relative to the standard global mean. The standardized dietary intake estimates were converted to centered percentiles for each DII component, multiplied by the corresponding component-specific inflammatory effect scores, and then summed to obtain the overall score for each individual (sTable 1). The EDII scores were calculated by adjusting for energy expenditures per 1000 kcal. To facilitate further analysis, the DII and EDII scores were evenly divided into tertiles, ensuring a balanced classification of dietary inflammatory potential across the study population.

Covariables assessment and ascertainment of brain disorders outcomes

Detailed information on sociodemographic and lifestyle factors was collected by a self-administered touchscreen questionnaire and interview, and physical measurements and biological samples were collected using standardized procedures. Further information on the covariates used in this study can be found in sMethods 2.

The following clinical outcomes were studied: (1) neurological disease, including ACD, AD, PD, sleep disorder, and stroke; (2) psychiatric disorders, including anxiety and depression disorders. The brain disorders were ascertained and classified according to the corresponding three-character ICD codes (sTable 2), obtained through hospital admissions and death registries linked to the UK biobank. The case ascertainment in the UK Biobank cohort is also described in sMethods 3.

Inflammation markers

Inflammation markers, including neutrophils, monocytes, platelets, lymphocytes and the concentration of CRP, were collected from blood count and biochemistry (category 100081&17518). Additionally, we calculated NLR (neutrophils/lymphocytes), platelet-to-lymphocyteratio (PLR) (platelets/lymphocytes), SII (neutrophils × platelets/lymphocytes) and lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR) (lymphocytes/monocytes). The processing and analysis step of blood sample can be found in the UKB data sources (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/label.cgi?id=100080).

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of participants were presented as mean (SD) for continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables. Comparisons were performed using t tests for continuous variables and χ 2 test for categorical variables. The reduced rank regression [RRR] constructs uncorrelated linear combinations of food groups that explain the maximize variation in the DII and EDII score, which were selected as intermediate variation. After adjusting for age, sex, race or ethnicity, Townsend Index of deprivation, education, BMI, smoking status, and physical activity, we used restricted cubic splines [RCS] fitted for Cox proportional hazards with 3 knots at the 10th, 50th, 90th percents of DII and EDII to evaluate the nonlinear associations and built multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate hazard ratios [HRs] of brain disorder across continuous DII and EDII scores and three-level score categories. Linear trend tests were performed for increasing three-level categories of DII and EDII by treating the means of the three-level categories as continuous variables. FDR correction was applied to obtain FDR-corrected P for the analyses of DII and EDII score with brain disorders and proportional hazards of the associations were tested using Schoenfeld’s residuals without indicating a violation of the model assumptions.

The structural equation models [SEM] were used to investigate the association of diet with brain disorders mediated by inflammation. The latent variable of brain disorders was measured in the model using ACD, anxiety, and depression, adjusting for the same set of covariables as in the Cox proportional hazards model.

Several sensitivity analyses were performed to ensure the reported results were robust. A sensitivity analyses with more covariates, including the history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia, were performed. With the total number of follow-ups increasing from 1 visit to 5 visits, the average follow-up time and the number of brain disorders events showed a significantly reduced (sFig. 2). Therefore, the RCS and Cox proportional hazards models were repeated only among participants who complete 2+ online dietary assessments to investigate potential bias in relation to random variation in individual intakes as sensitive analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the Study population

A total of 164,863 of the 502,411 UK biobank participants had available dietary recalls at baseline, including covariates relevant to this cohort study. The baseline characteristics of the study participants according to the tertiles of the DII score and EDII score were shown in Table 1 and sTable 4. The mean (SD) age of the participants was 58.97 (8.05) years, 53.2% were female, 95.9% were white, and the mean (SD) education years was 7.49 (2.97). Depending on the endpoint being investigated, the size of participants cohorts varied upon prevalent disease exclusion. Among them, the study included 2154 participants with incident ACD, 963 with AD, 1110 with PD, 2922 with sleep disorder, 4804 with stroke, 6959 with anxiety, and 5298 with depression (sTable 5).

Both DII and EDII scores were normally distributed across the study population, with ranges from −6.5 to 5.5 and from −4.5 to 7 points, respectively. Dietary inflammatory potential was characterized by positive loadings for low-fiber bread and butter, other animal fat and negative loadings for vegetables, fruit, oily fish, and high-fiber bread (Fig. 2A and sTable 6). This suggests that vegetables, fruit, fish oil, and high-fiber foods have anti-inflammatory effects, while low-fiber bread and animal fats have pro-inflammatory effects. Compared with the lowest DII score or EDII score, those in the highest DII or EDII score tended to be younger, female, had lower education and income, were likely to smoke, less likely to be white and exercise and have a higher BMI.

A Factor Loadings for Food Groups in dietary inflammatory potential. B Results were derived from RCS regression models adjusted for age and sex, race and ethnicity, educational levels, and lifestyle factors including body mass index, smoking status, physical activity. Solid lines represent hazard ratios and dotted line represent corresponding 95% CIs, using restricted cubic splines with knots at the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles and with median DII and EDII score as reference. The density plots indicate the distribution of the population. Values in bold indicate findings that have remained significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons. Abbreviations: DII Dietary inflammatory index, EDII Energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index, ACD all-cause dementia, AD Alzheimer’s disease, PD Parkinson’s disease, RCS restricted cubic splines.

Association of DII and EDII score with brain disorders

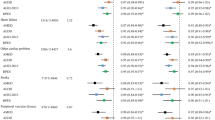

The RCS analyses identified evidence of nonlinear associations between DII and EDII scores with ACD, AD, sleep disorder, stroke, anxiety, and depression (Fig. 2B). In multivariable-adjusted models, we found a positive association for each deviation increase in DII score with risk of ACD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.039 [95% CI 1.011–1.068], corrected P = 0.009), sleep disorder (HR, 1.036 [95% CI 1.013–1.060], corrected P = 0.004), stroke (HR, 1.020 [95% CI 1.002–1.038], corrected P = 0.044), anxiety (HR, 1.039 [95% CI 1.024–1.054], corrected P < 0.001), depression (HR, 1.036 [95% CI 1.019–1.054], corrected P < 0.001) and EDII score with risk of ACD (HR, 1.090 [95% CI 1.031–1.154], corrected P = 0.002), sleep disorder (HR, 1.079 [95% CI 1.036–1.123], corrected P < 0.001), anxiety (HR, 1.042 [95% CI 1.024–1.061], corrected P < 0.001), and depression (HR, 1.036 [95% CI 1.014–1.058], corrected P < 0.001) (Fig. 3 and sTable 7).

The blue forest plot represents the Cox regression model results for the DII score, while the orange forest plot represents the Cox regression model results for the EDII score. Results were derived from Cox regression models adjusted for age and sex, race and ethnicity, educational levels, and lifestyle factors including body mass index, smoking status, physical activity. Corrected P: aFDR corrected P for DII and EDII continuous scores; bFDR corrected P for trend. Abbreviations: DII Dietary inflammatory index, EDII Energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index, ACD all-cause dementia, AD Alzheimer’s disease, PD Parkinson’s disease.

Furthermore, participants with the highest DII score compared with the lowest DII score had a higher risk of ACD by 16.5% (95% CI 1.038–1.307), sleep disorder by 17.2% (95% CI 1.064–1.291), stroke by 11.0% (95% CI 1.029–1.197), anxiety by 18.4% (95% 1.111–1.261), depression by 13.6% (95% CI 1.057–1.221). Similarly, the significantly higher risk of ACD (HR, 1.177 [95% CI 1.048 − 1.321]), PD (HR, 1.176 [95% CI 1.006–1.375]), sleep disorder (HR, 1.166 [95% CI 1.058–1.286]), stroke (HR, 1.106 [95% CI 1.025–1.192]), anxiety (HR, 1.177 [95% CI 1.105–1.253), and depression (HR, 1.131 [95% CI 1.052–1.215]) were observed among those with higher EDII score tertiles (Fig. 3). Tests for linear trend suggested a linear relationship of DII with ACD (corrected P = 0.012 for trend), sleep disorder (corrected P = 0.002 for trend), stroke (corrected P = 0.012 for trend), anxiety (corrected P < 0.001 for trend), depression (corrected P = 0.014 for trend) and EDII with ACD (corrected P = 0.02 for trend), sleep disorder (corrected P = 0.002 for trend), stroke (corrected P = 0.012 for trend), anxiety (corrected P < 0.001 for trend), depression (corrected P = 0.014 for trend).

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analysis, HRs for incident brain disorders (including ACD, 1.167 (1.038–1.313); sleep disorder, 1.154 (1.044–1.274); stroke, 1.104 (1.022–1.193); anxiety, 1.184 (1.110–1.264); depression, 1.201 (1.066–1.352)) were still statistically significant after further adjusting for the baseline presence of comorbidities (sTable 8). When participants with completed 2 + 24-h online dietary assessment were included, results from Cox proportional hazards regression analyses on endpoints remained similar. ACD, sleep disorder, stroke and anxiety were associated with higher DII scores, although the associations of dietary inflammatory potential with PD and depression were no longer significant (sTable 8). After further excluding individuals with a follow-up period of less than 5 years, we observed that ACD, anxiety, and depression remained significantly associated with higher DII and EDII scores (sTable 9).

Association of inflammation with DII, EDII score and brain disorders

To further investigate the association of DII and EDII score with inflammation, we evaluated the relationship between DII and EDII with blood count and biochemistry in a subsample of 167,010 participants with available data. The most significant inflammation markers associated with DII and EDII scores included the concentration of CRP, WBC, Neutrophil, SII, and Lymphocyte (Fig. 4A, B, sTable 10). In addition, CRP, WBC, Neutrophil, NLR, SII have been associated with a variety of neuropsychiatric diseases, especially dementia, anxiety and depression.

All models used age as the underlying time variable and were adjusted for sex, body mass index, race and ethnicity, physical activity level, smoking status, education level. A Associations of DII scores with inflammation markers. B Associations of EDII scores with inflammation markers. C Structural equation model. Latent variables including brain disorders and brain structures were estimated in the model. Abbreviations: DII Dietary inflammatory index, EDII Energy-adjusted dietary inflammatory index, ACD all-cause dementia, AD Alzheimer’s disease, PD Parkinson’s disease.

Structural equation model

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to examine the latent variables in the structural equation model including brain disorders. The results demonstrated that depression symptoms and anxiety symptoms were the main components of brain disorders’ latent variable. The results demonstrated that DII and EDII scores were associated with inflammation, and inflammation was associated with brain disorders. The indirect pathway of the effect of DII and EDII scores on brain disorders via inflammation (DII: indirect effect [IE] = 0.001; EDII: IE = 0.001). (Fig. 4C, sTable 11).

Discussion

In this cohort study, the prospective analyses of UK biobank data provide a comprehensive assessment of dietary inflammatory potential with risk of brain disorders and brain structures. Several findings are particularly noteworthy: (1) participants in the highest tertiles of DII and EDII scores exhibited the greatest risk for incident ACD, sleep disorder, stroke, anxiety, and depression; (2) DII and EDII scores were significantly associated with inflammation; (3) the inflammation was a significant mediator for the relationship of dietary inflammatory potential with brain structures and brain disorders.

In recent years, the role of dietary inflammatory potential in leading to human aging has garnered much interest [18], and their associations with brain disorders [19], including depression [20, 21], cardiovascular disease [22], dementia [23], and intermediate risk factors for brain disorders, including obesity [24,25,26], diabetes [12, 26], hypertension [26,27,28]. Recent studies have shown that the proinflammatory diet was positively associated with an increased risk of depression [29,30,31], stroke [22, 32, 33], and dementia [23, 34]. Importantly, we observed the association of DII/EDII scores with anxiety disorder and PD in this large-scale, population-based study. One possible reason for no associations of dietary inflammatory potential with PD in sensitivity analyses is that the number of case participants and the length of the follow-up period were insufficient. Our finding highlights that certain food components, such as fruits, vegetables, fish oils, and high-fiber breads, exhibit substantial anti-inflammatory effects. Conversely, animal fats and low-fiber breads appear to promote inflammation. This evidence aligns with the extensive body of research underscoring the anti-inflammatory benefits of fruits and vegetables and the pro-inflammatory characteristics of animal fats [35, 36]. Such findings are consistent with the growing body of literature exploring the intricate links between dietary patterns and inflammation [37, 38]. Despite the relationship between an inflammatory diet and brain disorders has not been extensively studied, our findings were in agreement with studies that have reported associations between existing dietary patterns, including the Mediterranean dietary pattern and Western dietary pattern, and brain disorders outcomes in older individuals. Adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern, which was inversely associated with inflammation, reduced the risk of depression [39, 40], anxiety [39], stroke [41, 42], PD [43,44,45], dementia [46], higher cognition function [47]. However, the Western dietary pattern, which has been shown to induce inflammatory responses [48,49,50], increased the risk of brain disorders [21, 51, 52]. Overall, It is increasingly apparent that anti-inflammatory dietary pattern, such as the Mediterranean dietary pattern-characterized by higher intakes of fruit, vegetables, and whole grains, is associated with lower risk of a diverse range of neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions.

Several mechanisms may underlie the associations between diet quality and the risk of brain disorders. First, one interpretation of those associations seen in our study may be related to systemic inflammation caused by inflammatory diet. Increasing levels of circulating proinflammatory cytokines have been associated with neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [53,54,55,56,57]. Second, proinflammatory diet may result in metabolic imbalances that lead to type 2 diabetic mellitus [58], unfavorable lipoproteins [59], and metabolic syndrome [25, 59], all of those may increase the risk of brain disorders. Third, dietary pattern may change the intestinal microbiome composition and that microbiome composition influence the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders [60,61,62]. Forth, some nutrients, such as choline, reduced the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders by inhibiting inflammation. A diet supplemented with choline lead to a decrease inflammation, resulting in a decrease in AD pathology [63]. Further insight into the association between dietary inflammatory potential and brain structure comes from the primary discoveries under the associations of dietary inflammatory potential with brain disorders. Previous findings showed that a higher score of an inflammation-related nutrient pattern was associated with smaller total brain volume [TBV] and total gray matter volume [TGMV] [64, 65]. In addition, results from previous studies investigating associations of dietary patterns with cortical thickness and hippocampal volume support our study, finding either positive associations with Mediterranean dietary patterns or a negative association with the Western dietary pattern [66,67,68,69]. Our results indicated that adherence to an anti-inflammatory diet such as the Mediterranean dietary pattern may lead to healthy aging in older adults.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this cohort study include a large sample size, a prospective design with long-term follow-up, long-term and repeated measures of diet, and observed associations between dietary inflammatory potential and brain health. However, our study has several important limitations. First, dietary intake information was based on self-reported, which may introduce measuring errors. Second, the calculation of DII and EDII scores is limited by the lack of complete information on several dietary nutrients. Third, 39.7% of participants had only one 24-h recall and may be prone to measurement error owing to its limited ability to fully capture individuals’ variation in diet. Finally, although we adjusted for a broad range of relevant potential confounders, the possibility of residual confounding influencing our results remains.

Conclusions

In conclusion, pro-inflammatory diets were associated with higher risk of brain disorders, such as ACD, PD, stroke, anxiety, and depression, and some brain regions. Inflammation was a significant mediator for the relationship of dietary inflammatory potential with brain structures and brain disorders. Our study indicated a shift toward food intake that emphasizes anti-inflammatory diet to improve health. However, further studies are needed to clarify the risk of brain disorders in relation to a pro-inflammatory diet among more racially diverse populations.

Availability of data and materials

The main data used in this study were accessed from the publicly available UK Biobank Resource under application number 19,542, which cannot be shared with other investigators. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the UK Biobank (https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/showcase/index.cgi) upon application.

Code availability

All data management and analyses were performed using R version 4.0.1 using the data. table package version 1.14.0, the dplyr package version 1.0.2, the Mice package, and the car package version 3.0.10. Figures were plotted using ggplot2 version 3.2.1. Additionally, stringr package version 1.4.0 and fst package version 0.9.4 were used for data management. Scripts used to perform the analyses are available at https://github.com/yanfu-a/Diet_inflammation.

References

GBD 2016 Neurology Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18:459–80.

Olesen J, Leonardi M. The burden of brain diseases in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2003;10:471–7.

Peskind ER, Li G, Shofer JB, Millard SP, Leverenz JB, Yu CE, et al. Influence of lifestyle modifications on age-related free radical injury to brain. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1150–4.

Amor S, Woodroofe MN. Innate and adaptive immune responses in neurodegeneration and repair. Immunology. 2014;141:287–91.

Haapakoski R, Ebmeier KP, Alenius H, Kivimäki M. Innate and adaptive immunity in the development of depression: an update on current knowledge and technological advances. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;66:63–72.

Simpson CA, Diaz-Arteche C, Eliby D, Schwartz OS, Simmons JG, Cowan CSM. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression – a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;83:101943.

Minihane AM, Vinoy S, Russell WR, Baka A, Roche HM, Tuohy KM, et al. Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: current research evidence and its translation. Br J Nutr. 2015;114:999–1012.

Szarc vel Szic K, Declerck K, Vidaković M, Vanden Berghe W. From inflammaging to healthy aging by dietary lifestyle choices: is epigenetics the key to personalized nutrition? Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:33.

Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Hébert JR. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1689–96.

Hébert JR, Shivappa N, Wirth MD, Hussey JR, Hurley TG. Perspective: the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII)—lessons learned, improvements made, and future directions. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:185–95.

Neufcourt L, Assmann KE, Fezeu LK, Touvier M, Graffouillère L, Shivappa N, et al. Prospective association between the dietary inflammatory index and cardiovascular diseases in the SUpplémentation en VItamines et Minéraux AntioXydants (SU.VI.MAX) Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002735.

Laouali N, Mancini FR, Hajji-Louati M, El Fatouhi D, Balkau B, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and type 2 diabetes risk in a prospective cohort of 70,991 women followed for 20 years: the mediating role of BMI. Diabetologia. 2019;62:2222–32.

Zhang J, Feng Y, Yang X, Li Y, Wu Y, Yuan L, et al. Dose-response association of dietary inflammatory potential with All-cause and cause-specific mortality. Adv Nutr. 2022;13:1834–45.

Collins R. What makes UK biobank special? Lancet. 2012;379:1173–4.

Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779.

Schofield WN. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum Nutr Clin Nutr. 1985;39 Suppl 1:5–41.

Liu B, Young H, Crowe FL, Benson VS, Spencer EA, Key TJ, et al. Development and evaluation of the Oxford WebQ, a low-cost, web-based method for assessment of previous 24 h dietary intakes in large-scale prospective studies. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:1998–2005.

Martínez CF, Esposito S, Di Castelnuovo A, Costanzo S, Ruggiero E, De Curtis A, et al. Association between the inflammatory potential of the diet and biological aging: a cross-sectional analysis of 4510 adults from the Moli-Sani Study Cohort. Nutrients. 2023;15:1503.

Marx W, Veronese N, Kelly JT, Smith L, Hockey M, Collins S, et al. The dietary inflammatory index and human health: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of Observational studies. Adv Nutr. 2021;12:1681–90.

Adjibade M, Lemogne C, Touvier M, Hercberg S, Galan P, Assmann KE, et al. The inflammatory potential of the diet is directly associated with incident depressive symptoms among french adults. J Nutr. 2019;149:1198–207.

Matison AP, Mather KA, Flood VM, Reppermund S. Associations between nutrition and the incidence of depression in middle-aged and older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational population-based studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;70:101403.

Peng M, Wang L, Xia Y, Tao L, Liu Y, Huang F, et al. High dietary inflammatory index is associated with increased plaque vulnerability of carotid in patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020;51:2983–9.

Sokratis C, Eva N, Mary Y, Costas AA, Mary HK, Efthimios D, et al. Diet inflammatory index and dementia incidence. Neurology. 2021;97:e2381.

Navarro P, Shivappa N, Hébert JR, Mehegan J, Murrin CM, Kelleher CC, et al. Predictors of the dietary inflammatory index in children and associations with childhood weight status: a longitudinal analysis in the Lifeways Cross-Generation Cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:2169–79.

Khan I, Kwon M, Shivappa N, Hébert RJ, Kim MK. Proinflammatory dietary intake is associated with increased risk of metabolic syndrome and its components: results from the Population-Based Prospective study. Nutrients. 2020;12:1196.

Hariharan R, Odjidja EN, Scott D, Shivappa N, Hébert JR, Hodge A, et al. The dietary inflammatory index, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors and diseases. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13349.

Phillips CM, Chen LW, Heude B, Bernard JY, Harvey NC, Duijts L, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and non-communicable disease risk: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2019;11:1873.

Hébert JR, Shivappa N, Wirth MD, Hussey JR, Hurley TG. Perspective: the Dietary Inflammatory Index (DII)-lessons learned, improvements made, and future directions. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:185–95.

You Y, Chen Y, Yin J, Zhang Z, Zhang K, Zhou J, et al. Relationship between leisure-time physical activity and depressive symptoms under different levels of dietary inflammatory index. Front Nutr. 2022;9:983511.

Tolkien K, Bradburn S, Murgatroyd C. An anti-inflammatory diet as a potential intervention for depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:2045–52.

Luo L, Hu J, Huang R, Kong D, Hu W, Ding Y, et al. The association between dietary inflammation index and depression. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1131802.

Li J, Lee DH, Hu J, Tabung FK, Li Y, Bhupathiraju SN, et al. Dietary inflammatory potential and risk of cardiovascular disease among men and women in the U.S. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2181–93.

Shivappa N, Godos J, Hébert JR, Wirth MD, Piuri G, Speciani AF, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and cardiovascular risk and mortality-a meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2018;10:200.

Hayden KM, Beavers DP, Steck SE, Hebert JR, Tabung FK, Shivappa N, et al. The association between an inflammatory diet and global cognitive function and incident dementia in older women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory study. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:1187–96.

Almeida-de-Souza J, Santos R, Lopes L, Abreu S, Moreira C, Padrão P, et al. Associations between fruit and vegetable variety and low-grade inflammation in Portuguese adolescents from LabMed Physical Activity study. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:2055–68.

Chai W, Morimoto Y, Cooney RV, Franke AA, Shvetsov YB, Le Marchand L, et al. Dietary red and processed meat intake and markers of adiposity and inflammation: the multiethnic Cohort study. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36:378–85.

Wu PY, Chen KM, Tsai WC. The mediterranean dietary pattern and inflammation in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. 2021;12:363–73.

Barbaresko J, Koch M, Schulze MB, Nöthlings U. Dietary pattern analysis and biomarkers of low-grade inflammation: a systematic literature review. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:511–27.

Sadeghi O, Keshteli AH, Afshar H, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P. Adherence to Mediterranean dietary pattern is inversely associated with depression, anxiety and psychological distress. Nutr Neurosci. 2021;24:248–59.

Oddo VM, Welke L, McLeod A, Pezley L, Xia Y, Maki P, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower depressive symptoms among U.S. adults. Nutrients. 2022;14:278.

Stewart RA, Wallentin L, Benatar J, Danchin N, Hagström E, Held C, et al. Dietary patterns and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in a global study of high-risk patients with stable coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1993–2001.

Fung TT, Rexrode KM, Mantzoros CS, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Mediterranean diet and incidence of and mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Circulation. 2009;119:1093–100.

Metcalfe-Roach A, Yu AC, Golz E, Cirstea M, Sundvick K, Kliger D, et al. MIND and Mediterranean diets associated with later onset of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2021;36:977–84.

Molsberry S, Bjornevik K, Hughes KC, Healy B, Schwarzschild M, Ascherio A. Diet pattern and prodromal features of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2020;95:e2095–e2108.

Zhang X, Xu J, Liu Y, Chen S, Wu S, Gao X. Diet quality is associated with prodromal Parkinson’s disease features in chinese adults. Mov Disord. 2022;37:2367–75.

Shannon OM, Ranson JM, Gregory S, Macpherson H, Milte C, Lentjes M, et al. Mediterranean diet adherence is associated with lower dementia risk, independent of genetic predisposition: findings from the UK Biobank Prospective Cohort study. BMC Med. 2023;21:81.

Mattei J, Bigornia SJ, Sotos-Prieto M, Scott T, Gao X, Tucker KL. The Mediterranean diet and 2-year change in cognitive function by status of type 2 diabetes and glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:1372–9.

Christ A, Latz E. The Western lifestyle has lasting effects on metaflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:267–8.

Christ A, Günther P, Lauterbach MAR, Duewell P, Biswas D, Pelka K, et al. Western diet triggers NLRP3-dependent innate immune reprogramming. Cell. 2018;172:162–175.e114.

Christ A, Lauterbach M, Latz E. Western diet and the immune system: an inflammatory connection. Immunity. 2019;51:794–811.

Dearborn-Tomazos JL, Wu A, Steffen LM, Anderson CAM, Hu EA, Knopman D, et al. Association of dietary patterns in midlife and cognitive function in later life in US adults without dementia. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1916641.

Shi H, Schweren LJS, Ter Horst R, Bloemendaal M, van Rooij D, Vasquez AA, et al. Low-grade inflammation as mediator between diet and behavioral disinhibition: a UK Biobank study. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;106:100–10.

Wang Q, Liu Y, Zhou J. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease and its potential as therapeutic target. Transl Neurodegener. 2015;4:19.

Irani SR, Nath A, Zipp F. The neuroinflammation collection: a vision for expanding neuro-immune crosstalk in Brain. Brain. 2021;144:e59.

Perry VH, Holmes C. Microglial priming in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:217–24.

Khandaker GM, Pearson RM, Zammit S, Lewis G, Jones PB. Association of serum interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein in childhood with depression and psychosis in young adult life: a Population-Based Longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1121–8.

McGrattan AM, McGuinness B, McKinley MC, Kee F, Passmore P, Woodside JV, et al. Diet and inflammation in cognitive ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Nutr Rep. 2019;8:53–65.

Denova-Gutiérrez E, Muñoz-Aguirre P, Shivappa N, Hébert JR, Tolentino-Mayo L, Batis C, et al. Dietary inflammatory index and type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: the diabetes mellitus survey of Mexico city. Nutrients. 2018;10:385.

Phillips CM, Shivappa N, Hébert JR, Perry IJ. Dietary inflammatory index and biomarkers of lipoprotein metabolism, inflammation and glucose homeostasis in adults. Nutrients. 2018;10:1033.

Komaroff AL. The microbiome and risk for atherosclerosis. JAMA. 2018;319:2381–2.

Dodiya HB, Kuntz T, Shaik SM, Baufeld C, Leibowitz J, Zhang X, et al. Sex-specific effects of microbiome perturbations on cerebral Aβ amyloidosis and microglia phenotypes. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1542–60.

Lee KE, Kim JK, Han SK, Lee DY, Lee HJ, Yim SV, et al. The extracellular vesicle of gut microbial Paenalcaligenes hominis is a risk factor for vagus nerve-mediated cognitive impairment. Microbiome. 2020;8:107.

Judd JM, Jasbi P, Winslow W, Serrano GE, Beach TG, Klein-Seetharaman J, et al. Inflammation and the pathological progression of Alzheimer’s disease are associated with low circulating choline levels. Acta Neuropathol. 2023;146:565–83.

Gu Y, Manly JJ, Mayeux RP, Brickman AM. An inflammation-related nutrient pattern is associated with both brain and cognitive measures in a multiethnic elderly population. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2018;15:493–501.

Melo Van Lent D, Gokingco H, Short MI, Yuan C, Jacques PF, Romero JR, et al. Higher Dietary Inflammatory Index scores are associated with brain MRI markers of brain aging: results from the Framingham Heart Study Offspring Cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:621–31.

Staubo SC, Aakre JA, Vemuri P, Syrjanen JA, Mielke MM, Geda YE, et al. Mediterranean diet, micronutrients and macronutrients, and MRI measures of cortical thickness. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:168–77.

Gu Y, Brickman AM, Stern Y, Habeck CG, Razlighi QR, Luchsinger JA, et al. Mediterranean diet and brain structure in a Multiethnic Elderly cohort. Neurology. 2015;85:1744–51.

Karstens AJ, Tussing-Humphreys L, Zhan L, Rajendran N, Cohen J, Dion C, et al. Associations of the Mediterranean diet with cognitive and neuroimaging phenotypes of dementia in healthy older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109:361–8.

Jacka FN, Cherbuin N, Anstey KJ, Sachdev P, Butterworth P. Western diet is associated with a smaller hippocampus: a longitudinal investigation. BMC Med. 2015;13:215.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all UK Biobank participants for their time and UK Biobank team members for collating the data. This study was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Innovation 2030 Major Projects (2022ZD0211600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82071201, 82071997, 82271475), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2018SHZDZX01), Research Start-up Fund of Huashan Hospital (2022QD002), Excellence 2025 Talent Cultivation Program at Fudan University (3030277001), Shanghai Talent Development Funding for The Project (2019074), Shanghai Rising-Star Program (21QA1408700), 111 Project (B18015), and ZHANGJIANG LAB, Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute, the State Key Laboratory of Neurobiology and Frontiers Center for Brain Science of Ministry of Education, and Shanghai Center for Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Technology, Fudan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr Yu and Cheng had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Yu. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Fu, Chen. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Fu, Chen. Obtained funding: Yu. Administrative, technical, or material support: Ou, Wang, Gao. Supervision: Yu, Cheng, Feng.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The UK Biobank study received approval from the National Health Service (NHS) North West Multicenter Research Ethics Committee. All participants were informed of consent via electronic signature prior to participation in the study. Analysis was performed under application number 19542 and the study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, Y., Chen, SJ., Wang, ZB. et al. Dietary inflammatory index and brain disorders: a Large Prospective Cohort study. Transl Psychiatry 15, 99 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03297-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03297-4