Abstract

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) changes play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but their effects on other pathological processes, such as neurodegeneration and amyloid-β deposition, are unclear. We investigated the correlations between cerebral perfusion measured with arterial spinal labeling (ASL) and cerebral metabolism and amyloid deposition on positron emission tomography (PET) scans in AD. Sixty-four AD patients and 56 cognitively unimpaired controls were included. Cerebral perfusion was indicated by the expression of AD-related perfusion pattern (ADRP), global CBF and the relative value of regional CBF. The standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) of regions of interest (ROIs) was calculated for 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET and 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB)-PET images in AD patients. The subject expression score of ADRP showed strong negative correlations with FDG SUVR in all ROIs and a positive correlation with PiB SUVR in temporal. FDG SUVR in some ROIs were also positively correlated with global CBF and relatively regional CBF in the temporoparietal cortex, precuneus and posterior cingulate, and negatively correlated with relatively regional CBF in the thalamus and pre- and postcentral regions. The PiB SUVR of the ROIs were negatively correlated with the relatively regional CBF in the left inferior parietal region and were positively correlated with the relatively regional CBF in the right thalamus and left precentral regions. CBF was significantly correlated with hypometabolism and amyloid deposition in AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia in elderly people and has become one of the most lethal, costly and burdensome diseases worldwide in this century [1]. The hallmark neuropathological characteristics of AD are the diffuse presence of neuritic plaques, which are extracellular deposits of amyloid-β (Aβ), and neurofibrillary tangles, which are intraneuronal aggregates of hyperphosphorylated tau protein [2, 3]. Recent fundamental findings highlighted that in addition to the core signature of Aβ and tau pathology, there are many other important pathological mechanisms, such as neurodegeneration, which can be measured via cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or plasma levels of neurofilament light chain, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET, and neuroinflammation [4] and cerebrovascular dysfunction [5], all of which have been suggested to be additional biomarkers for AD.

Notably, accumulating evidence has demonstrated that cerebral blood flow (CBF) change, which is attributed to cerebral vascular dysfunction, is a potential early biomarker and may play a crucial role in driving cognitive decline in AD patients [5,6,7]. Community-based neuropathological studies have shown a significantly greater prevalence of cerebrovascular pathology in AD patients than other neurodegenerative disease, such as α-synucleinopathy, prion disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration due to tau, highlighting the underappreciated contributory role of vascular impairment in the pathogenesis of AD [8, 9]. In addition, neuroimaging studies have shown that CBF is obviously changed in persons on the AD continuum and CBF change is a sensitive biomarker for cognitive decline in symptomatic individuals [10,11,12]. In our previous study, both relatively decreased and increased CBF in different brain regions measured with arterial spin labeling (ASL), which is a noninvasive technique in MRI, were observed in AD patients after normalizing global CBF values [13]. Moreover, an AD-related perfusion pattern (ADRP) was established using a multivariate spatial covariance method of a scaled subprofile model (SSM) based on principal component analysis (PCA), and this pattern showed stronger and more extensive correlations with cognitive performance than did global and regional CBF in AD patients [13].

Perfusion and metabolism are biologically coupled, and it was found that they had similar brain maps or patterns in patients with AD [14,15,16], suggesting that ASL could also be an alternative to FDG PET to support the diagnosis of AD and other neurodegenerative diseases without radioactivity and being much less expensive. However, the correlations between CBF changes in characteristic regions and brain networks and FDG metabolism in significant brain areas have still not been established.

The two-hit hypothesis proposes a complex relationship between microvascular insults and Aβ accumulation at the origin of disease development in AD [17]. This hypothesis was demonstrated by several animal studies showing that altered CBF caused by vascular damage led to an upregulation of the β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 responsible for generating toxic Aβ peptides, leading to increased Aβ production and deposition and subsequently to tau aggregation, neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment [18,19,20]. However, findings on the correlation between regional CBF and Aβ deposition have been inconsistent in previous clinical studies [21, 22]. Since changes in both CBF and amyloid deposition are distinct in different brain regions across the disease course, more studies are needed to elucidate the complex relationship between perfusion and Aβ pathology.

In the present study, we aimed to reveal the important effects of perfusion changes on the neurodegeneration and core pathology of Aβ in AD. We investigated the associations between cerebral perfusion, indicated by both the subject expression score of the ADRP and the global and regional CBF measured with ASL, and cerebral metabolism and Aβ deposition on PET scans in patients with AD.

Subjects and methods

Participants

In the present study, 64 patients with AD and 56 age- and sex-matched cognitively unimpaired (CU) controls were recruited from the memory clinic of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital. Written informed consent was provided by all participants. Demographics, medical history, and the results of physical and neurological examinations, comprehensive neuropsychological assessments, laboratory tests, and brain MRI scans were collected. AD patients also underwent FDG and 11C-Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) PET scans.

Patients with AD met the research diagnostic criteria for typical AD of the International Working Group-2 (IWG-2) [23]. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (1) aged 50–85 years; (2) had early and prominent episodic memory impairment; (3) had no evidence of clinically significant cerebrovascular lesions or extensive white matter hyperintensities on MRI (Fazekas score [24] < 2); and (4) had a positive result for Aβ deposition measured with PiB PET. Patients whose cognitive impairment was potentially caused by other neurological diseases, mental disorders or medical conditions, such as frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Parkinson’s disease or dementia with Lewy bodies, vascular dementia, multiple sclerosis, hydrocephalus, alcohol or drug abuse, severe depression, thyroid dysfunction, vitamin B12 deficiency, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or neurosyphilis, were excluded. Patients with atypical presentations, such as posterior cortical atrophy, logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia and behavioral or dysexecutive frontal variant of AD, for which the perfusion and metabolism patterns are probably distinct from those of typical AD, were also excluded.

CU controls demonstrated no subjective cognitive decline and normal performance in each cognitive domain of objective neuropsychological tests, with a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [25] score of 0 and a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [26] score > 26. None of the CU controls showed clinically significant atrophy in the medial temporal lobe or other brain areas or cerebrovascular disease on MRI.

MRI acquisition and imaging data processing

All MRI scans were acquired on a 3.0-Tesla MRI scanner (Discovery MR750, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA) using a 8-channel phased array head coil. The following parameters were used for the coronal TI-weighted 3D brain volume sequence scan: echo time/repetition time (TE/TR): 3.2 ms/8.2 ms, flip angle (FA): 12°, field of view (FOV): 256 × 256 × 188 mm3, matrix size: 256 × 256, NEX = 1, slice thickness: 1.0 mm, number of slices: 188. 3D pseudo-continuous ASL was performed to measure whole-brain perfusion using 3D fast spin‒echo acquisition and background suppression with the following parameters: TE/TR: 11.1 ms/5046 ms, labeling duration: 1450 ms, post labeling delay: 2025 ms, FA: 111°, matrix size: 128 × 128, FOV: 240 × 240 × 150 mm3, arms = 8, acquisition points = 512, slice thickness: 3 mm, and number of slices: 50. At the same time, a proton density image was also acquired to quantify the CBF from the ASL series. Each participant was instructed to remain calm, to not move their forehead, and to not fall asleep during the resting-state ASL scan. No participants used any drugs that could affect CBF within two weeks before the MRI examination, and alcohol, coffee, or nicotine was prohibited for at least 6 h prior to MRI examination. All MRI scans for AD patients were acquired within one month after the PET scans.

The MRI data were preprocessed with statistical parametric mapping (SPM12, Institute of Neurology, London, UK) and MATLAB (Version R2015a, MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) according to the procedure as previously described [13]. All processed images of the CBF and tissue maps had matrix dimensions of 121 × 145 × 121 and voxel sizes of 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm3 in the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) brain template. The subject expression score of the ADRP, which was identified and validated in our previous study [13], was obtained for CBF images on a prospective single-case basis using a voxel-based algorithm in the SSM/PCA toolbox for each participant in this study.

All data analysis was performed within an average brain mask using SPM12 software. The whole-brain gray matter of all subjects was calculated using MATLAB software, with age, sex and educational levels as covariates. The CBF values of patients with AD and CU controls were compared with a two-sample t test. With a voxel-level peak threshold of P < 0.05 (family wise error-corrected, FWE-corrected) across all brain regions, we identified clusters > 150 voxels after adjusting for global values with analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). The MNI coordinates of the voxel points with significant differences were obtained. The Brodmann area (BA) was obtained using Talairach–Daemon software (Research Imaging Center, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio, TX, USA), which queried the functional brain region corresponding to the MNI coordinates. The SPM maps were overlaid on a standard T1-weighted MRI brain template in stereotaxic space. The relative CBF values in specific cortical regions in the volume of interest (a 4 mm radius spherical) were obtained by calculating their ratio to the global CBF values in all participants with SPM12 software.

PET imaging acquisition

FDG and PiB PET scans were conducted on the same day at the PET/X-ray computed tomography (CT) center of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital with a GE Discovery LS PET/CT scanner in 3D scanning mode as described in our previous publication [27]. PiB was injected into the antecubital vein as a bolus (mean dose: 370–555 MBq), and images were acquired during a 90 min dynamic PET scan (34 frames: 4 × 15 s, 8 × 30 s, 9 × 60 s, 2 × 180 s, 8 × 300 s, 3 × 600 s). At a minimum of 1 h after PiB injection, the subjects were intravenously injected with 259 MBq of FDG and then underwent a 10-min static PET scan 40 min after FDG injection. Each frame produced 47 slices of 3.75 mm thickness that covered the whole brain. All PET images were reconstructed to a 256 × 256 matrix (pixel size of 1.37 mm2). All subjects fasted for at least 6 h before tracer injection and remained calm and did not move their heads during the scan.

PET data processing

All PET images were manually checked for quality by two trained investigators, and the data were processed according to the procedure used in previous studies [27, 28]. For FDG, we mapped five regions of interest (ROIs), including the right and left angular gyrus, bilateral posterior cingulate gyrus, and right and left inferior temporal gyrus, which have been demonstrated to show the most robust changes in AD patients in previous studies [27, 29]. Standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) maps were generated by normalizing the raw counts to the mean uptake in the pons and cerebellar vermis. PiB uptake was systematically evaluated in several cortical areas, including the bilateral frontal lobe, lateral temporal lobe, lateral parietal lobe, precuneus/posterior cingulate gyrus, and cerebellum. Amyloid PET positivity was defined as increased PiB retention in the cerebral cortex compared with that in the cerebellum in at least one target region. Two experienced nuclear medicine physicians independently performed the visual assessments, with final determinations reached through consensus. The validity of this qualitative approach has been previously established, demonstrating high concordance with the quantitative analysis methods used in our previous study [30, 31]. For PiB PET processing, the frontal, orbitofrontal, parietal, and temporal lobes are typical brain regions known to have high Aβ deposition and to correlate with the progression of disease in AD patients [32, 33]. According to the prior studies, the frontal, orbitofrontal, parietal, temporal, anterior cingulate gyrus, posterior cingulate gyrus, and precuneus were selected as ROIs in the present study. The PiB SUVR of each ROI was obtained normalizing to the cerebellar crus grey.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 26.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The demographic and clinical variables, as well as the subject expression scores of the ADRP, global CBF value and relative value of regional CBF, were compared between the AD and CU groups using the Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables or two-sample t test for continuous variables. Partial correlations were used to assess the relationships between cerebral perfusion and glucose metabolism and amyloid deposition, with age, sex and educational levels as covariates. All figures were generated by using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) and OriginLab Origin 2021 (OriginLab Inc., Northampton, Massachusetts, USA). All tests were two-tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Demographics and clinical variables of the study population

The demographics and clinical variables of all participants are shown in Table 1. There was no difference in age or sex between the AD and CU groups. Patients with AD had fewer years of education than did the CU controls (P = 0.014). In terms of vascular risk factors, there was no difference in hypertension or diabetes history between the AD and CU groups. MMSE scores were lower in patients with AD than in CU controls (P < 0.001).

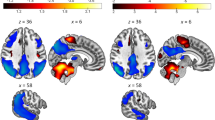

Differences in ADRP expression and CBF between AD patients and CU controls

According to voxel-based analysis, CBF in the bilateral posterior cingulate, bilateral middle cingulate, bilateral precuneus, bilateral inferior parietal lobule, bilateral inferior temporal, and bilateral angular was relatively decreased, and CBF in the bilateral postcentral, bilateral precentral, bilateral thalamus, left cerebellar, and right putamen was relatively increased in AD patients compared with CU controls (FWE corrected, P < 0.05) after ANCOVA normalization for the global value and adjustment for age, sex and educational levels (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

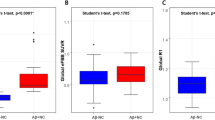

Patients with AD had significantly higher subject expression scores of the ADRP (P < 0.001) and lower global CBF (P = 0.018) compared with CU controls (Fig. 2A, B). Sample plots for the regions with significantly changed relative CBF in the AD group are shown in Fig. 2C, D.

The comparison of the ADRP subject expression score A global CBF B and values in regions with relatively decreased CBF C and values in regions with relatively increased CBF D between AD patients and CU controls, obtained post hoc within a spherical volume of interest (4 mm radius). The relative CBF values were calculated by the ratio of the volume of interest values to the global CBF values. Data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). CBF cerebral blood flow, AD alzheimer’s disease, CU cognitively unimpaired, L left, R right. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Association between perfusion and metabolism in patients with AD

Subject expression scores of the ADRP showed significantly negative correlations with all FDG SUVR ROIs in this study (Fig. 3A–E), including bilateral angular (left: r = −0.717, P < 0.001; right: r = −0.729, P < 0.001), posterior cingulate (r = −0.587, P < 0.001), and bilateral inferior temporal (left: r = −0.536, P < 0.001; right: r = −0.610, P < 0.001). Positive correlations were found between the global CBF and FDG SUVR in the bilateral angular (left: r = 0.296, P = 0.022; right: r = 0.316, P = 0.014), posterior cingulate (r = 0.296, P = 0.022), and right inferior temporal (r = 0.312, P = 0.015) but not in the left inferior temporal (r = 0.190, P = 0.146), as shown in Fig. 3F–J.

There were negative correlations between the subject expression score of the ADRP and FDG SUVR in left angular (A), right angular (B), posterior cingulate (C), left inferior temporal (D), and right inferior temporal (E). Global CBF was positively correlated with FDG SUVR in left angular (F), right angular (G), posterior cingulate (H), and right inferior temporal (J), but not left inferior temporal (I). These correlations were identified after adjusting for age, sex and educational levels. ADRP AD-related perfusion pattern, FDG fluorodeoxyglucose, SUVR standardized uptake value ratio, CBF cerebral blood flow, L left, R right.

The correlations between the relative values of the regional CBF and FDG SUVR of the ROIs are presented in Fig. S1. For regions with relatively decreased CBF in the AD group, relative CBF values in the bilateral angular, left inferior temporal and posterior cingulate were positively correlated with the FDG SUVR in all ROIs. There were also positive correlations between relative CBF values in the left inferior parietal and FDG SUVR in all ROIs except the posterior cingulate, between the right precuneus and FDG SUVR in all ROIs except for the left inferior temporal, between the right inferior temporal and FDG SUVR in the posterior cingulate, right angular, and right inferior temporal. For regions with relatively increased CBF in the AD group, relative CBF values in the bilateral thalamus were negatively correlated with the FDG SUVR in all ROIs. Other negative correlations between the relative CBF value and FDG SUVR were observed, including the left postcentral and FDG SUVR in all ROIs except the left angular, the left precentral and FDG SUVR in all ROIs except the left inferior temporal, and the right precentral and FDG SUVR in the posterior cingulate and bilateral inferior temporal.

Association between perfusion and Aβ deposition in patients with AD

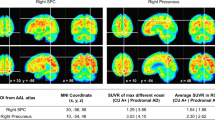

The associations between the subject expression score of the ADRP and global CBF and PiB SUVR in all ROIs are presented in Fig. 4. There was a positive correlation between the subject expression score of the ADRP and the PiB SUVR in the temporal (r = 0.291, P = 0.023) but not in any other ROI. No significant correlations were found between the global CBF and the PiB SUVR of any of the ROIs.

The correlations between the relative values of the regional CBF and the PiB SUVR of all ROIs are presented in Fig. S2. In general, a negative correlation for relatively decreased CBF in AD patients and a positive correlation for relatively increased CBF in AD patients were observed. Specifically, there were negative correlations between the relative values of the CBF in the left inferior parietal and the PiB SUVR in the prefrontal (r = −0.296, P = 0.022), orbital frontal (r = −0.264, P = 0.035), temporal (r = −0.303, P = 0.015) and posterior cingulate (r = −0.257, P = 0.040), and positive correlations between the relative values of the CBF in the right thalamus and the PiB SUVR in the posterior cingulate (r = 0.260, P = 0.039), temporal (r = 0.316, P = 0.011), parietal (r = 0.301, P = 0.016), and precuneus (r = 0.388, P = 0.002), and between the relative values of the CBF in the left precentral and the PiB SUVR in the temporal (r = 0.278, P = 0.025).

Discussion

This study revealed prominent correlations between perfusion measured with ASL, including both the specific perfusion network and characterized regional CBF, and glucose metabolism measured with FDG PET and Aβ deposition measured with PiB PET in various brain areas. These results further demonstrated the coupling of CBF and cerebral metabolism, and the ability of the ADRP to reflect the progression of disease and neurodegeneration because of its strong correlation with all characteristic regions of hypometabolism on FDG PET in AD patients. Moreover, although the causal relationship between changes in CBF and Aβ deposition could still not be determined, their close correlation with the development of AD was suggested according to our findings.

Mounting evidence has shown that alterations in cerebral perfusion occur at early stages and existed in the whole course of the AD continuum. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have consistently revealed decreased CBF in patients with AD [34,35,36], and correlations between longitudinal changes in global CBF and further cognitive decline [35], suggesting that CBF is a potential biomarker for the identification and progression monitoring of AD. Similar to previous findings [10, 37, 38], both relatively decreased CBF, mainly in the temporoparietal cortex and posterior cingulate and precuneus, and increased CBF in the primary cortex (e.g., pre- and postcentral), thalamus and cerebellum were found in AD patients after adjusting for global values in this study.

The ADRP is a characteristic perfusion pattern of AD established using a multivariate analysis method based on SSM/PCA in our previous study, which included an identification cohort and a validation cohort [13]. Moreover, extensive correlations between subject expression score of the ADRP and cognitive function in various domains were found. In the present study, we verified the prominent increase in ADRP expression in AD patients compared with that in CU controls and further demonstrated a significant negative correlation between ADRP expression and FDG SUVR in all ROIs, and a positive correlation between ADRP expression and PiB SUVR in temporal after controlling for age, sex and education levels, suggesting the potential value of ADRP not only for screening and diagnosis but also for monitoring Aβ deposition and neurodegeneration in AD patients.

CBF is critical for brain function because it ensures adequate delivery of glucose, oxygen and nutrients to the brain as well as the removal of carbon dioxide and cellular waste. In present study, we analyzed the correlations between global CBF, relative values in regions with hypoperfusion or hyperperfusion according to group comparison in SPM analysis and FDG SUVR of ROIs in patients with AD. We found that global CBF and the relative values of almost all regions with relatively decreased CBF in AD patients were positively correlated with the FDG SUVR of some ROIs, supporting a general correlation between CBF and glucose metabolism [39, 40].

In contrast, negative correlations were found between the relative values in regions with relatively increased CBF in AD, such as the thalamus and pre- and postcentral regions and the FDG SUVR of some ROIs. CBF measured with ASL was previously shown to be negatively correlated with cerebral metabolism measured with FDG PET in subcortical regions of autosomal dominant AD patients, including the amygdala, hippocampus and insula [41]. Another study revealed that although there was an overall good correlation between CBF and metabolism, there was considerable regional variability in healthy adults [42]. The regional discrepancies between CBF and metabolism could be attributed to neurovascular decoupling during the development of AD. Moreover, we used relative values to represent regional perfusion in this study, which normalized global CBF changes in each individual. Therefore, an increased relative value indicated relative preservation under the condition of a general decline in CBF in the whole brain. The negative correlations also suggest neurovascular coupling for the whole brain beyond regions with preserved CBF in AD patients.

Although it has been recognized that CBF change is an early and persistent pathophysiological process in AD, findings on its correlation with Aβ deposition are still inconclusive. We found that the relative CBF, particularly in the left inferior parietal region, which is one of the characteristic hypoperfusion regions in AD patients, was negatively correlated with the Aβ load in the prefrontal, orbital frontal, temporal and posterior cingulate regions in this study. An early study revealed that the brain Aβ load on PET was significantly associated with the regional CBF measured with ASL at early stages of Aβ pathology in the absence of clinical dementia [21]. Moreover, an association between high amyloid deposition and regional hypoperfusion was found in AD-relevant anatomical ROIs, such as the temporal, frontal and parietal lobes, hippocampus, and insula, in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease patients [41]. Taken together, our results validated previous findings of the correlation between CBF changes and Aβ pathology, although whether hypoperfusion contributes to an increase in Aβ production and a decrease in Aβ clearance or whether Aβ toxicity leads to vascular dysfunction could not be determined in the present study. Experimental studies revealed that Aβ deposition could reduce CBF, induce neurovascular dysfunction, and increase the susceptibility of the brain to ischaemia, suggesting that AD pathology could promote vascular pathology [43]. On the other hand, cerebrovascular system dysfunction can stimulate Aβ generation and impair its clearance, leading to pathological accumulation of Aβ in the brain [44, 45]. Accordingly, current evidence supports a bidirectional synergistic interaction between Aβ deposition and CBF changes rather than a unidirectional causal relationship. Future studies employing longitudinal multimodal imaging combined with molecular biomarkers, particularly including individuals in the early biological stages of AD, are essential to elucidate the spatiotemporal dynamics of this interaction.

Similar to the FDG results, the opposite correlation was also observed for relative values in the regions with relatively increased CBF in AD patients and Aβ deposition. Positive correlations between CBF and Aβ load have been found in persons with AD or unimpaired cognition, specifically in the hippocampus, caudate, insula, posterior cingulate, and precuneus regions [21, 46]. Apart from using relative CBF values in this study, another possible explanation for this positive correlation is that hyperperfusion might reflect a mechanism compensating for Aβ neurotoxicity [22, 47, 48].

There were several limitations in the current study. First, this study included a relatively small sample size and included only symptomatic AD patients whose Aβ tracer uptake values almost plateaued, making the PiB SUVR within a small range across all patients. Secondly, since all the results were obtained via cross-sectional analysis, the causal relationships between perfusion changes and metabolism, Aβ pathology could not be clarified. The current findings need to be replicated in a larger cohort with long-term follow-up including individuals at different pathological stages, e.g., from no AD core pathology to mild to severe Aβ deposition. Moreover, although demographics, such as age, sex and educational level, were controlled for during correlation analysis, we admit that variation in CBF changes might still be partly attributed to age and sex. In addition, other factors that might influence perfusion, metabolism or Aβ deposition, such as APOE genotype and cerebrovascular risk factors and lesions, were not considered. Finally, for FDG and PiB ROIs, we focused on only some large lobes, not more delicate brain areas, and we did not analyze their correlations with CBF in the same region.

In conclusion, this study revealed positive correlations between hypoperfusion in specific regions and hypometabolism, Aβ deposition in several brain lobes in AD patients, suggesting the coupling of CBF and neuronal and synaptic activity, and the relationship between vascular and AD core pathology. Furthermore, ADRP, a perfusion pattern established by spatial covariance analysis, is a promising marker for the diagnosis, monitoring and evaluation of AD.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7:e105–e125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00249-8

Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M, Holstege H, Chetelat G, Teunissen CE et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2021;397:1577–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4

Duyckaerts C, Delatour B, Potier MC. Classification and basic pathology of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:5–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-009-0532-1

Venegas C, Kumar S, Franklin BS, Dierkes T, Brinkschulte R, Tejera D et al. Microglia-derived ASC specks cross-seed amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2017;552:355–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25158

Korte N, Nortley R, Attwell D. Cerebral blood flow decrease as an early pathological mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2020;140:793–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-020-02215-w

Iadecola C. Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:347–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1387

Niwa K, Kazama K, Younkin SG, Carlson GA, Iadecola C. Alterations in cerebral blood flow and glucose utilization in mice overexpressing the amyloid precursor protein. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;9:61–8. https://doi.org/10.1006/nbdi.2001.0460

Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, Nation DA, Schneider LS, Chui HC et al. Vascular dysfunction-the disregarded partner of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers. Dement. 2019;15:158–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.222

Toledo JB, Arnold SE, Raible K, Brettschneider J, Xie SX, Grossman M et al. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the national Alzheimer’s coordinating centre. Brain. 2013;136:2697–706. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt188

Duan W, Sehrawat P, Balachandrasekaran A, Bhumkar AB, Boraste PB, Becker JT et al. Cerebral blood flow is associated with diagnostic class and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76:1103–20. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200034

Dong H, Guo L, Yang H, Zhu W, Liu F, Xie Y et al. Association between gray matter atrophy, cerebral hypoperfusion, and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1129051. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1129051

Alexopoulos P, Sorg C, Forschler A, Grimmer T, Skokou M, Wohlschlager A et al. Perfusion abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia in Alzheimer’s disease measured by pulsed arterial spin labeling MRI. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry. Clin. Neurosci. 2012;262:69–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-011-0226-2

Meng M, Liu F, Ma Y, Qin W, Guo L, Peng S et al. The identification and cognitive correlation of perfusion patterns measured with arterial spin labeling MRI in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2023;15:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-023-01222-9

Musiek ES, Chen Y, Korczykowski M, Saboury B, Martinez PM, Reddin JS et al. Direct comparison of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and arterial spin labeling magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers. Dement. 2012;8:51–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.06.003

Riederer I, Bohn KP, Preibisch C, Wiedemann E, Zimmer C, Alexopoulos P et al. Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment: integrated pulsed arterial spin-labeling MRI and 18F-FDG PET. Radiology. 2018;288:198–206. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018170575

Tosun D, Schuff N, Rabinovici GD, Ayakta N, Miller BL, Jagust W et al. Diagnostic utility of ASL-MRI and FDG-PET in the behavioral variant of FTD and AD. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2016;3:740–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.330

Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;12:723–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3114

Zhiyou C, Yong Y, Shanquan S, Jun Z, Liangguo H, Ling Y et al. Upregulation of BACE1 and beta-amyloid protein mediated by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion contributes to cognitive impairment and pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2009;34:1226–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-008-9899-y

Sun X, He G, Qing H, Zhou W, Dobie F, Cai F et al. Hypoxia facilitates Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis by up-regulating BACE1 gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18727–32. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0606298103

Johnston JA, Liu WW, Todd SA, Coulson DT, Murphy S, Irvine GB et al. Expression and activity of beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:1096–100. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20051096

Mattsson N, Tosun D, Insel PS, Simonson A, Jack CJ, Beckett LA et al. Association of brain amyloid-beta with cerebral perfusion and structure in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Brain. 2014;137:1550–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu043

Rischel EB, Gejl M, Brock B, Rungby J, Gjedde A. In Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid beta accumulation is a protective mechanism that ultimately fails. Alzheimers. Dement. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12701

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:614–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0

Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 t in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1987;149:351–6. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.149.2.351

Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–72. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.140.6.566

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, Mchugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

Liu F, Shi Y, Wu Q, Chen H, Wang Y, Cai L et al. The value of FDG combined with PiB PET in the diagnosis of patients with cognitive impairment in a memory clinic. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024;30:e14418. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.14418

Jack CJ, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Therneau TM, Lowe VJ, Knopman DS et al. Defining imaging biomarker cut points for brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers. Dement. 2017;13:205–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.08.005

Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Foster NL et al. Associations between cognitive, functional, and FDG-PET measures of decline in AD and MCI. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32:1207–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.07.002

Wang Y, Shi Z, Zhang N, Cai L, Li Y, Yang H et al. Spatial patterns of hypometabolism and amyloid deposition in variants of Alzheimer’s disease corresponding to brain networks: a prospective cohort study. Mol. Imaging. Biol. 2019;21:140–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11307-018-1219-6

Zhang N, Zhang L, Li Y, Gordon ML, Cai L, Wang Y et al. Urine AD7c-NTP predicts amyloid deposition and symptom of agitation in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60:87–95. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170383

Klunk WE, Koeppe RA, Price JC, Benzinger TL, Devous MS, Jagust WJ et al. The centiloid project: standardizing quantitative amyloid plaque estimation by PET. Alzheimers. Dement. 2015;11:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.07.003

Jack CJ, Knopman DS, Chetelat G, Dickson D, Fagan AM, Frisoni GB et al. Suspected non-Alzheimer disease pathophysiology-concept and controversy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016;12:117–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.251

Asllani I, Habeck C, Scarmeas N, Borogovac A, Brown TR, Stern Y. Multivariate and univariate analysis of continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 2008;28:725–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600570

Weijs R, Shkredova DA, Brekelmans A, Thijssen D, Claassen J. Longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow and their relation with cognitive decline in patients with dementia: current knowledge and future directions. Alzheimers. Dement. 2023;19:532–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12666

Camargo A, Wang Z. Longitudinal cerebral blood flow changes in normal aging and the Alzheimer’s disease continuum identified by arterial spin labeling MRI. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2021;81:1727–35. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210116

Dai W, Lopez OL, Carmichael OT, Becker JT, Kuller LH, Gach HM. Mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease: patterns of altered cerebral blood flow at MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;250:856–66. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2503080751

Ding B, Ling HW, Zhang Y, Huang J, Zhang H, Wang T et al. Pattern of cerebral hyperperfusion in Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment using voxel-based analysis of 3D arterial spin-labeling imaging: initial experience. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2014;9:493–500. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S58879

Jueptner M, Weiller C. Review: does measurement of regional cerebral blood flow reflect synaptic activity? Implications for PET and FMRI. Neuroimage. 1995;2:148–56. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.1995.1017

Chen Y, Wolk DA, Reddin JS, Korczykowski M, Martinez PM, Musiek ES et al. Voxel-level comparison of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI and FDG-PET in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:1977–85. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823a0ef7

Yan L, Liu CY, Wong KP, Huang SC, Mack WJ, Jann K et al. Regional association of pCASL-MRI with FDG-PET and PiB-PET in people at risk for autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage Clin. 2018;17:751–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2017.12.003

Cha YH, Jog MA, Kim YC, Chakrapani S, Kraman SM, Wang DJ. Regional correlation between resting state FDG PET and pCASL perfusion MRI. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 2013;33:1909–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2013.147

Iadecola C. The neurovascular unit coming of age: a journey through neurovascular coupling in health and disease. Neuron. 2017;96:17–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.07.030

Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, Glodzik L, Butler T, Fieremans E et al. Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11:457–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.119

Gertsik N, Chiu D, Li YM. Complex regulation of γ-secretase: from obligatory to modulatory subunits. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015;6:342. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00342

Fazlollahi A, Calamante F, Liang X, Bourgeat P, Raniga P, Dore V, et al. Increased cerebral blood flow with increased amyloid burden in the preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2020;51:505–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26810

Ossenkoppele R, Madison C, Oh H, Wirth M, van Berckel BN, Jagust WJ. Is verbal episodic memory in elderly with amyloid deposits preserved through altered neuronal function? Cereb. Cortex. 2014;24:2210–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bht076

Cohen AD, Price JC, Weissfeld LA, James J, Rosario BL, Bi W, et al. Basal cerebral metabolism may modulate the cognitive effects of Abeta in mild cognitive impairment: an example of brain reserve. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14770–8. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3669-09.2009

Funding

This work was supported by Tianjin Public Health Science and Technology Major Project (24ZXGZSY00060), Science and Technology Innovation 2030—Major Projects (2021ZD0201805, 2022ZD0211605), and the Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (TJYXZDXK-004A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PC wrote the manuscript. LC and YW performed the procedure of PET scan and made quality control for the images. QL, ZP, and XZ analyzed the PET images. WQ conducted the MRI procedure and acquired the imaging data. FL and YW analyzed the ASL MRI data. PC and YZ performed statistical analysis. NZ conceived and designed the study and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Che, P., Cai, L., Liu, F. et al. Cerebral perfusion is correlated with cerebral metabolism and amyloid deposition in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry 15, 189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03402-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03402-7