Abstract

Background

Aggression, while evolutionarily adaptive, becomes maladaptive when it violates social norms and inflicts harm, posing significant societal and clinical challenges. Despite extensive research, the neural mechanisms underlying aggression remain poorly understood due to inconsistent findings and the network localization of aggression remains underexplored.

Methods

This study synthesized findings from 91 neuroimaging studies, including 56 studies on trait aggression (1387 aggressive and 1251 non-aggressive individuals) and 40 studies on elicited aggression (2651 individuals), to identify brain regions implicated in aggression and constructed probability maps of aggression-related brain abnormality networks. We applied functional connectivity network mapping combined with large-scale brain connectome data to localize aggression-related structural and functional brain alterations into three distinct networks: gray matter volume, task-induced activation, and resting-state activity.

Results

The aggression gray matter volume abnormality network encompassed widespread regions, including the insula, superior temporal gyrus, and cingulate cortex, predominantly involving the salience networks. The task-induced activation abnormalitynetwork implicated the basal ganglia and anterior salience networks, with subgroup analyses revealing distinct patterns between elicited and trait aggression. The resting-state activity abnormality network involved the dorsal default mode and visual networks.

Conclusions

These findings provide a unified framework for understanding aggression’s neurobiology from a network perspective, addressing prior inconsistencies. The identified networks may serve as biomarkers for refining brain stimulation targets and guiding pharmacological or psychological interventions to mitigate aggression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aggression, while evolutionarily essential for survival, becomes maladaptive and destructive when it violates social norms and is intended to inflict verbal or physical harm, cause chaos, or even lead to injury or death [1]. Such behaviors impose a significant burden on society. Certain psychiatric populations demonstrate a higher prevalence of violent or aggressive behavior compared to the general population, including individuals with schizophrenia [2], antisocial or borderline personality disorders [3, 4], and intermittent explosive disorder [5]. For instance, in patients with schizophrenia, violent behavior can result in poor treatment outcomes, prolonged hospitalization, stigmatization [6], physical harm, and social loss [7], posing severe challenges to patients, their families, and healthcare professionals.

Although various risk factors for violent behavior have been identified—for example, individuals with violent behavior beginning before the onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorder are more likely to have lived in socially disorganized neighborhoods, whereas those with violent behavior beginning after the onset of the disorder are more often associated with clinical risk factors such as substance misuse, impaired executive functions, poor impulse control, delusions, and lack of illness insight [8]—the predictive and translational value of non-biological risk factors remains limited. Consequently, uncovering the neural mechanisms underlying aggression has become a key focus of neuroscience as well as social, clinical, personality, and forensic psychology [9]. Advancing our understanding of the biological processes predisposing individuals to aggression is essential for identifying effective therapeutic targets and validating neural biomarkers to improve assessment, management, prediction, and intervention strategies [10].

Advances in multimodal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have provided significant opportunities to investigate aggression-related alterations in brain structure and function. However, meta-analyses of structural studies have reported inconsistent findings. For example, Widmayer et al. [11] found lower volumes in the whole brain and specific regions, such as the prefrontal cortex and thalamus, alongside higher volumes in the amygdala and putamen in violent compared to non-violent individuals with schizophrenia. In contrast, another study [10] reported no significant differences in gray matter volume between violent and non-violent individuals with schizophrenia. Meta-analyses [12] of functional correlates of aggression in psychiatric disorders suggest that escalated aggression arises from abnormal activity in the precuneus within the fronto-parietal network (FPN), disrupting the recruitment of other large-scale networks such as the adaptive cognitive control network (CCN). This pattern was observed in both trait aggression (involving individuals with a history of violent incidents and high aggression scores on psychological scales) and elicited aggression (studies using experimental paradigms to provoke aggression in laboratory settings, such as the Taylor Aggression Paradigm [13], Point Subtraction Aggression paradigm [14] and violent video games [15]). A small number of resting-state studies have highlighted the relevance of aberrant basal ganglia-prefrontal circuits in aggression [16].

Despite these efforts, prior research has struggled to identify a convergent set of anatomical regions responsible for aggression. Recent lesion network mapping analyses have shown that lesions in diverse brain regions can result in similar symptoms by mapping onto a shared neural network, defined by their functional connectivity [17]. For some symptoms, lesion locations are connected to multiple regions or networks that may need to be affected simultaneously to produce the observed behavior [17]. This has led to the emergence of functional connectivity network mapping (FCNM) as an innovative and well-validated framework that shifts the focus from isolated regional findings to a network-based understanding of symptom localization. Recent applications of FCNM have yielded important mechanistic insights into a range of psychiatric phenomena, including auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia [18], suicide-related structural and functional abnormalities [19], and both neurocognitive and social cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia [20]. While FCNM has proven successful in domains that traditional methods struggled to localize [17], its application to aggression remains largely unexplored.

This exploratory study aimed to investigate the structural and functional brain networks associated with aggression. To achieve this, we synthesized findings from existing literature to identify brain regions exhibiting differences in gray matter volume and resting-state activity between aggressive and non-aggressive individuals and brain regions with aberrant activation pattern under laboratory aggression paradigms. Using these identified regions, we applied the FCNM approach to integrate them with large-scale discovery and validation resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) datasets. This method enabled us to construct three aggression-related brain abnormality networks corresponding to distinct imaging modalities. A detailed schematic illustrating the study design and analysis workflow is provided in Fig. 1.

We first searched related studies to identify brain structural and functional locations between violent and non-violent individuals A. Then, we adopted functional connectivity network mapping (FCNM) methods to construct three aggression brain abnormality networks corresponding to different imaging modalities with large-scale discovery and validation datasets B. Specifically, spheres centered on each coordinate of each contrast were created and combined together to generate a seed mask of each contrast. Second, we computed the resting-state FC on each participant using each seed mask. Third, the subject-level FC maps were entered into a voxel-wise one-sample t-test to identify brain regions that were functionally associated with each seed mask with a false discovery rate (FDR) corrected for multiple comparisons at p = 0.05. Finally, the binarized maps for the grey matter volume, task-induced activation, and resting-state activity contrasts were overlayed to generate 3 aggression brain damage networks probability maps of grey matter volume, task-induced activation, and resting-state activity threshold at 60%, respectively C-D.

Methods and materials

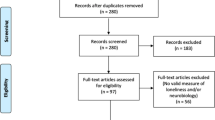

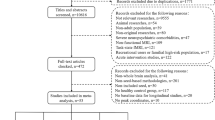

Literature search and selection

We conducted a systematic literature search in the PubMed and Web of Science databases, including studies through June 2024. The search utilized keywords and further details are provided in the Supplementary Materials. Our search was not limited to any specific diagnoses, as we assumed a common network of aggression exists across different disease contexts. Each study’s analysis focused on individual contrasts, as a single study could report multiple contrasts. For each significant cluster reported in a contrast, the peak voxel coordinates were extracted, with Talairach coordinates converted to MNI space when necessary. This systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, registration number: CRD42024579896). Figure 2 outlines the PRISMA-based search strategy.

Discovery and validation datasets

We utilized a discovery dataset from the Consortium for Reliability and Reproducibility (CoRR, https://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/CoRR/html/index.html) [21]. After removing sites with less than 10 sample sizes and subjects with poor imaging quality and incomplete brain coverage, the final 30 sites including 1315 healthy individuals (665 female; mean age 26.48) were included. The validation datasets from four additional sites including 182 healthy individuals (88 female; mean age 26.50) recruited from the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University and Second Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University. All participants were screened to exclude those with first-degree relatives with a history of psychosis and head trauma, substance abuse, neurological disorders, severe organic lesions (e.g., tumors, cardiac disease, thyroid dysfunction), pregnancy or lactation, and MRI contraindications. Full details of demographic information of the discovery and validation datasets have been described in Table S1 and Fig. S1.

fMRI data acquisition and preprocessing

The fMRI scanning parameters of the discovery and validation datasets are provided in Table S2. In validation sites, participants were instructed to lie supine and remain awake with their eyes closed during the scan. Foam pads and soft earplugs were used to minimize head movement and reduce scanner noise. Participants exhibiting excessive head movement (more than 2 mm translation or 2° rotation) were excluded from the analysis.

Neuroimaging data were preprocessed using the Data Processing & Analysis for Brain Imaging (DPABI) software (https://www.rfmri.org/DPABI) [22]. The first 10 time points were discarded to ensure signal stability. The remaining data underwent slice-timing and head motion correction and were spatially normalized to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space by Dartel methods, resampled to a 3 × 3 × 3 mm3 voxel size. Several nuisance covariates including Friston-24 head motion parameters, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid signals, and global signal were included in the regression analysis. The resulting images were smoothed with a 4 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel to reduce spatial noise. Then the data were band-pass filtered between 0.01–0.08 Hz to remove physiological noise, such as heartbeats and respiration.

Functional connectivity network mapping

We used the FCNM approach to construct networks of aggression brain structures and functional impairments between violent and non-violent individuals based on the extracted coordinates of gray matter volume, task-induced activation, and resting-state activity differences. First, for each contrast, 4 mm-radius spheres were generated around the reported coordinates and combined into a composite seed mask [18]. This contrast-level seed captures the distributed nature of aggression-related alterations and yields one FC map per contrast. Aggregating peaks in this manner enhances statistical power and reduces the multiple-comparisons burden. Second, voxel-wise FC was conducted for each participant and Fisher’s z-transformation was to improve normality. Then to remove confounding effects between different sites, we used the harmonization module of DPABI, which has been shown to have good reliability and reproducibility for reducing site effects (Fig. S2) [23]. Third, corrected subject-level FC maps were constructed to a voxel-wise one-sample t-test to identify brain regions that were functionally associated with each seed mask with a false discovery rate (FDR) corrected for multiple comparisons at P = 0.05. Finally, t-maps were binarized and were overlayed to generate 3 aggression brain abnormality networks probability maps of grey matter volume, task-induced activation, and resting-state activity threshold at 60%, respectively [18, 19].

Association with canonical brain networks

To facilitate brain network localization, we investigated the spatial correlation of 3 aggression brain networks with 14 canonical brain networks [24]. We calculated the proportion of overlapping voxels between each aggression network and the canonical network over all voxels within the canonical network to quantify the spatial association between them.

Validation analyses

Several validation analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the results. First, we used the same analyses on the validation datasets from the four independent sites to assess the impact of the choice of dataset. Then, as many of the relevant contrasts only dealt with violent male individuals and healthy males, we repeated the analysis steps with male individuals in the discovery and validation dataset, including the inclusion of literature. Finally, we conducted additional analyses on the 18–60-year-old subsample within the discovery cohort and applied alternative overlap thresholds (50 and 70%) to evaluate the stability of the results across different age ranges and methodological parameters.

Results

Included studies

A total of 91 studies met our inclusion criteria. Based on the contrasts reported, we categorized these studies into two groups: studies on trait aggression (TA) and studies on elicited aggression (EA). TA studies included individuals with a history of violence, such as violent offenders, compared to non-aggressive counterparts. In contrast, EA studies used behavioral paradigms to compare BOLD responses during induced aggression. Specifically, 17 TA studies, comprising 20 contrasts with 551 aggressive and 528 non-aggressive individuals, were included in the gray matter volume analysis. For the task-induced activation analysis, 71 studies were included: 33 TA studies (34 contrasts, 649 aggressive and 563 non-aggressive individuals) and 40 EA studies involving 2651 individuals. Additionally, six TA studies with six contrasts from 187 aggressive and 160 non-aggressive individuals were included in the resting-state activity analysis. Tables S3–S5 provide an overview of the study characteristics, while Table S6 details the quality assessment for each study.

Aggression gray matter volume abnormality network

The aggression-related gray matter volume abnormality network encompassed widely distributed brain regions, with key areas including the bilateral insula, superior temporal gyrus, and cingulate (Fig. 3A). When mapped onto canonical brain networks, this abnormality network was predominantly associated with the auditory (overlapping proportion: 65.91%), posterior salience (41.91%), and anterior salience (29.17%) networks (Fig. 4A).

Gray matter volume abnormality network A. Resting-state activity abnormality network B. Task-induced activation abnormality network C. Task-induced activation abnormality network in elicited aggression individuals D. Task-induced activation abnormality network in trait aggression individuals E. Polar plots show the proportion of overlapping voxels between each aggression network and a canonical brain network. DMN default mode network, LECN left executive control network, RECN right executive control network, EA elicited aggression, TA trait aggression.

Aggression resting-state activity abnormality network

The aggression resting-state activity abnormality network comprised more widely distributed brain areas mainly including the bilateral occipital lobes, superior frontal gyrus, precuneus, and hippocampus (Fig. 3B). Regarding canonical brain networks, the aggression resting-state activity abnormality network mainly involved the high visual (85.34%), dorsal default mode network (DMN) (65.01%), and primary visual (21.10%) networks (Fig. 4B).

Aggression task-induced activation abnormality network

The aggression task-induced activation abnormality network was located in the brain regions of the bilateral caudate (Fig. 3C). Regarding canonical brain networks, the aggression task-induced activation abnormality network mainly involved the basal ganglia (12.71%) networks (Fig. 4C).

Subgroup analysis

We classified violent individuals in the research literature into two categories, TA and EA, and carried out the same approach. However, the classification of EA is only differentiated in the task-induced activation studies. The brain regions of the aggression task-induced activation abnormality network in the EA group were predominantly distributed in the bilateral opercular part of the inferior frontal gyrus, putamen, and insula (Fig. S3A), mainly involved the basal ganglia (32.60%), and anterior salience (10.86%) networks (Fig. 4D). The brain regions of the aggression task-induced activation abnormality network in the TA group were predominantly distributed in the bilateral thalamus, opercular part of inferior frontal gyrus, and caudate (Fig. S3B), mainly involved the basal ganglia (14.92%) networks (Fig. 4E).

Validation analyses

First, aggression brain abnormality networks from the validation datasets were very similar to those from the discovery datasets, namely, gray matter volume abnormality network mainly located in the auditory and salience networks, and resting-state activity abnormality network located in the DMN, high visual, and precuneus networks (Figs. S4–S5). However, since the validation datasets’ sample size is much lower than the discovery datasets, brain regions with more than 60% overlapping regions were not found in the validation datasets in the task-induced activation abnormality network. Second, when we included literature and the discovery and validation datasets were all male individuals, we found that the results were closer to those of the full group and that the percentage of overlapping brain networks for all males was larger than for the full group (Figs. S6–S10). In addition, the overlapping networks identified in the adult subsample (Figs. S11–S12), as well as those obtained using 50 and 70% overlap thresholds (Figs. S13–S15), were highly similar to the main findings, indicating a high level of stability across different ages and methodological parameters. In summary, we constructed aggression brain abnormality networks with the gray matter volume abnormality network mainly consisting of the insula and temporal gyrus (the auditory and salience networks), the resting-state activity abnormality network mainly consisting of the occipital lobes, prefrontal lobe, precuneus (the DMN, visual, and precuneus networks), and the task-induced activation abnormality network mainly consisting of basal ganglia, particular caudate.

Discussion

Building on previously reported brain structural and functional alterations associated with aggression, this study explored the network localization of aggression, identifying three distinct brain abnormality networks across different imaging modalities. The gray matter volume abnormality network encompassed widespread regions, primarily involving the posterior and anterior salience networks and the superior temporal gyrus (a component of the dorsal medial subsystem of the DMN). The task-induced activation abnormality network included the anterior salience and basal ganglia networks, highlighting their relevance in aggression. The resting-state activity abnormality network was more broadly distributed, primarily involving the dorsal DMN and visual networks. These findings contribute to resolving prior discrepancies in neuroimaging studies and offer a deeper understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying aggression from a network-based perspective. This represents a crucial step toward the development of more targeted and effective evidence-based interventions for reducing aggression.

We found that the aggression gray matter volume abnormality network encompassed widely distributed brain regions, including the insula, superior temporal gyrus, and cingulate cortex. The insular cortex, which was also predominantly involved in the aggression task-induced activation abnormality network in the EA group, supports a broad range of functions in humans, from sensory and affective processing to high-level cognition [25]. Emerging evidence links abnormalities in the insula to aggression and callous-unemotional traits—such as a lack of guilt, inability to empathize, and the callous exploitation of others—across multiple psychiatric disorders [10, 26]. Craig [27] proposed that the insula is organized along a posterior-to-anterior gradient, reflecting a progressive integration of bodily sensations. He suggested that the posterior insula may be involved in processing acute emotions and interoceptive components, while the anterior insula might contribute to more abstract and highly integrated constructs. Given that aggression and retaliation elicit intense bodily sensations and immediate action tendencies, they may preferentially activate the posterior insula [28], with these signals subsequently integrated into more abstract representations within the anterior insula. As a key hub within the salience network, the anterior insula plays a critical role in empathy and social cognition, as demonstrated by numerous neuroimaging and lesion studies [25]. Furthermore, our findings that the insula is predominantly involved in the aggression task-induced activation abnormality network in the EA group align with prior evidence supporting the anterior insula’s central role in motor impulsivity and reactive aggression [26]. Notably, the insula’s involvement may not be exclusive to aggression. Its activation has been consistently reported in studies using a variety of emotionally arousing stimuli, such as images evoking disgust, fear, happiness, or sadness [29]. Explaining the functional roles of the insula requires considering the broader social and emotional contexts, as well as its interactions with interconnected brain regions [28].

By contrast, in the TA group, the bilateral thalamus emerged as the principal hub, along with the caudate and inferior frontal gyrus, suggesting a core thalamostriatal circuit underlying stable, trait-like aggressive behavior. The thalamus functions as a central relay gate, integrating sensory, affective, and limbic signals before broadcasting them to cortical regions involved in impulse control and decision-making [30]. Through its dense interconnections with the hypothalamus, it also regulates autonomic and neuroendocrine processes—such as HPA-axis activity—that shape long-term behavioral tendencies [31]. Resting-state connectivity analyses have shown that, in males, stronger aggression scores correlate with reduced coupling between the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and a cluster in the right mediodorsal thalamus (MD) [32], implicating this nucleus in trait-like aggression. Animal studies further support a modulatory role for thalamic nuclei: early work demonstrated that electrical stimulation of the thalamus could both elicit and suppress aggression, and that hypothalamus-induced attacks were contingent upon intact thalamic activity [33, 34]. In addition, fiber photometry studies have identified GABAergic projections from the LH to the paraventricular thalamus (PVT), revealing a neurochemical pathway through which hypothalamic signals modulate thalamic processing [35, 36]. Lesion and lesion-behaviour studies in rodents and cats confirm that MD or PVT disruption reduces aggressive responding [37, 38], while human thalamic lesions have been associated with disinhibited aggression [39]. Collectively, these findings suggest that thalamic hubs may mediate trait aggression by integrating subcortical motivational signals with cortical control systems, thus shaping enduring behavioral tendencies.

The striatum, known for its well-described topographic organization [40], also contains overlapping fibers from diverse cortical areas [41]. These overlaps function as hub connections, integrating information across cortical regions involved in decision-making processes, value associations and inhibitory control, highlighting the striatum’s role as a convergence site for prefrontal inputs [42, 43]. The dorsomedial striatum, in particular, appears to play a critical role in aggression; for example, it may help determine the value of responses to frustration, such as assaultiveness versus composed restraint [44]. Additionally, striatal event and action values are modulated by the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems. Dopamine signals the expected value of an event or action and adjusts its levels in response to outcomes that surpass or fail to meet expectations. Serotonin, in turn, regulates dopamine to influence temporal discounting, determining how the delay of a reward impacts its perceived value. Previous studies have emphasized the interaction between serotonergic modulation and dorsal striatal activity in punitive responses to unfair exchanges, with lower striatal serotonin transporter levels being associated with heightened aggression in patients with personality disorders [45, 46]. Research involving acute manipulations of serotonin (5-HT) availability in humans strongly supports the role of 5-HTergic system in regulating aggression [44, 47, 48]. The influence of 5-HT on aggression likely operates through neural networks involving the striatum, amygdala, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Notably, the relationship between 5-HT and aggression is complex and non-linear, with trait dimensions (e.g., aggression, impulsivity, psychopathy) and the type of aggression (e.g., reactive vs. proactive, normal vs. pathological) serving as key moderating factors [44]. Our findings from the task-induced activation abnormality network in the EA and TA groups suggest that therapies targeting the 5-HT system may hold potential as anti-aggressive treatments for both trait and reactive aggression.

Concerning canonical brain networks, the salience network and basal ganglia (subcortical) network play key roles in encoding the rewarding or punishing aspects of social interactions, providing control signals to guide behavioral adjustments in complex social environments [49]. The basal ganglia network is consistently engaged in mutual cooperation, altruistic giving, and costly punishment [49]. Conversely, norm violations induce negative emotions and error-like signals in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and anterior insula of the salience network, motivating individuals to adapt their behaviors or internal states to align with social norms [50]. Together, these networks constitute a shared neural motivation system that regulates decision-making across diverse individual and social contexts [49, 51]. In violent individuals, disruptions in the salience and basal ganglia networks may contribute to social cognitive deficits that directly impact violent behavior [52]. Such impairments could hinder the detection of social norm violations, preventing necessary behavioral adjustments. A broad-spectrum approach—combining cognitive training, social-cognitive training, and skills-based strategies targeting social and functional skills—shows promise for reducing violence [53]. Evidence suggests that cognitive training can reorganize neuroplasticity within the salience network and subcortical regions [54, 55]. However, the specific mechanisms underlying violence reduction through cognitive training in aggressive individuals with psychiatric disorders remain unclear. Future research is needed to address these gaps and further refine intervention strategies.

Beyond cognitive training, it will be important to examine whether direct modulation of the networks can ameliorate aggressive behaviors and induce corresponding neuroplastic changes. Although aggression-related networks are spatially distributed, the salience network consistently emerges across structural and functional modalities, identifying its nodes—particularly the ACC—as pragmatic intervention targets. For example, noninvasive brain stimulation techniques (e.g., deep transcranial magnetic stimulation) directed at the ACC could be evaluated in randomized controlled trials to assess whether normalizing salience-network activity produces measurable reductions in aggression. Longitudinal pre- and post-intervention MRI would allow for within-subject mapping of changes within the network and their relationship to behavioral improvement. Moreover, lifespan studies should investigate how these networks develop and reorganize from childhood through adulthood in relation to emerging aggression phenotypes, and whether early interventions can alter developmental trajectories. Finally, combining neurostimulation with pharmacological agents may reveal synergistic effects on both network function and aggressive behavior, paving the way for precision-guided, circuit-based therapies.

We noted that the salience network was manifested in both the aggression gray matter volume abnormality network and the task-induced activation abnormality network. Although its involvement was less extensive in the latter, this observation supports the view that structural brain abnormality may precede functional changes, either manifesting as sequential functional impairments along pre-existing structural damage pathways or as compensatory functional responses to structural abnormality [56, 57]. Beyond the salience network, the aggression task-induced activation abnormality network predominantly involved frontal and subcortical regions, particularly within the basal ganglia network. The limited number of studies included in the gray matter volume analysis may explain the more widely distributed cortical areas and the absence of basal ganglia regions in the gray matter volume abnormality network.

Our findings regarding the aggression-related resting-state activity abnormality network were somewhat unexpected, as it encompassed widely distributed brain areas, primarily involving the dorsal DMN and an extensive visual network. One interpretation is that the limited number of studies included in the resting-state activity analysis, along with the heterogeneous functional measures employed, may have constrained the identification of a more consistent distributed network. It is possible that aggression-related changes in different functional measures map onto distinct brain networks [19]. The occipital lobe, a key region for visual processing, is involved in object and face recognition, visuospatial processing, and visual memory formation [58]. Prior research suggests that the middle occipital cortex, along with the anterior insula, inferior frontal gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, and cingulate regions, is engaged during the processing of social disgust, while inferior occipital regions, in conjunction with limbic areas, play a critical role in early threat detection [59, 60]. Accordingly, the activation of the occipital cortex and associated regions in the resting state may indicate heightened vigilance or over-alertness in violent individuals.

Our study has several limitations. First, the included studies were heterogeneous in terms of participants’ diagnoses. While we assumed the existence of a common network associated with aggression across different diseases, we cannot exclude the possibility of distinct network substrates for aggression in specific conditions. Second, given that the majority of subjects in the included studies were male, our results primarily reflect the neural basis of aggression in men. Sex differences in aggressive behaviors are well-documented, even in children [61], with males typically displaying more physical aggression, whereas females tend to engage in more indirect forms of aggression such as social exclusion and gossiping [61, 62]. These behavioral differences may be rooted in genetic and hormonal factors. Neuroimaging studies have shown that females (regardless of hormonal contraceptive use) have greater gray matter volume in the dorsal ACC compared to males [63]. When provoked, males exhibit greater activation in the left amygdala, and their aggressive responses are positively correlated with activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, rectal gyrus, and ACC—patterns that contrast with the negative associations seen in females [64]. These findings highlight significant sex differences in the neural mechanisms underlying aggression. Moreover, several brain regions (the amygdala and hippocampus) implicated in aggression are rich in sex hormone receptors [65], suggesting that hormonal modulation may contribute to these neural disparities. Future research should investigate sex-specific neural networks of aggression to enhance our understanding of its neurobiological underpinnings and to inform the development of more tailored and effective interventions. Third, we used resting-state fMRI data from healthy adults to explore the network localization of aggression. While it would be preferable to utilize data from samples that closely match the demographic and clinical profiles of the selected studies’ participants, existing evidence suggests that sample selection has minimal impact on network localization results [19]. Fourth, information on race or ethnicity was unavailable in the discovery dataset, while all participants in the validation dataset were Han Chinese. The discovery dataset included participants from sites in China, the U.S., Germany, and Canada, suggesting potential ethnic heterogeneity. Fifth, we did not account for the sample size or effect size of each study in the FCNM analysis, as no consensus currently exists on how to incorporate these factors. Future studies, alongside methodological advances, should address this limitation to enhance analytical precision. Finally, we did not differentiate between increases and decreases in brain activity or volume in the included studies. Separate analyses of these changes could offer a more nuanced understanding of aggression, potentially distinguishing between compromised and compensatory networks [19].

In summary, this study applied functional connectivity network mapping alongside large-scale brain connectome data to identify distinct networks associated with aggression-related structural and functional brain alterations. These networks, corresponding to gray matter volume, task-induced activation, and resting-state activity, integrate findings from previous neuroimaging studies to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the neural basis of aggression from a network perspective. Importantly, the identified networks hold potential as clinical biomarkers, offering guidance for refining noninvasive brain stimulation targets and informing pharmacological or psychological interventions aimed at reducing aggression in violent individuals.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Code for the method section could be found: https://www.github.com/remenderfdif/FCNM.git.

References

Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:27–51.

Douglas KS, Guy LS, Hart SD. Psychosis as a risk factor for violence to others: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:679–706.

Soloff PH, Abraham K, Burgess A, Ramaseshan K, Chowdury A, Diwadkar VA. Impulsivity and aggression mediate regional brain responses in Borderline Personality Disorder: an fMRI study. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2017;260:76–85.

Dolan MC. What imaging tells us about violence in anti-social men. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2010;20:199–214.

Olvera RL. Intermittent explosive disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:517–26.

An I, Choi TK, Bang M, Lee SH. White matter correlates of hostility and aggression in the visuospatial function network in patients with schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:734488.

Hoptman MJ, Antonius D. Neuroimaging correlates of aggression in schizophrenia: an update. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:100–6.

Lamsma J, Harte JM, Cahn W, Genetic R, Outcome of Psychosis i. Risk factors for violent behaviour before and after the onset of schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a naturalistic case-control study in the Netherlands. Schizophr Res. 2023;262:1–7.

Denson TF, Pedersen WC, Ronquillo J, Nandy AS. The angry brain: neural correlates of anger, angry rumination, and aggressive personality. J Cogn Neurosci. 2009;21:734–44.

Wang YM, Wang Y, Cao Q, Zhang M. Aberrant brain structure in patients with schizophrenia and violence: a meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;164:447–53.

Widmayer S, Sowislo JF, Jungfer HA, Borgwardt S, Lang UE, Stieglitz RD, et al. Structural magnetic resonance imaging correlates of aggression in psychosis: a systematic review and effect size analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:217.

Wong TY, Sid A, Wensing T, Eickhoff SB, Habel U, Gur RC, et al. Neural networks of aggression: ALE meta-analyses on trait and elicited aggression. Brain Struct Funct. 2019;224:133–48.

Taylor SP. Aggressive behavior and physiological arousal as a function of provocation and the tendency to inhibit aggression. J Pers. 1967;35:297–310.

Cherek DR, Moeller FG, Dougherty DM, Rhoades H. Studies of violent and nonviolent male parolees: II. Laboratory and psychometric measurements of impulsivity. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:523–9.

Mathiak K, Weber R. Toward brain correlates of natural behavior: fMRI during violent video games. Hum Brain Mapp. 2006;27:948–56.

Gan G, Zilverstand A, Parvaz MA, Preston-Campbell RN, d’Oleire Uquillas F, Moeller SJ, et al. Habenula-prefrontal resting-state connectivity in reactive aggressive men - A Pilot study. Neuropharmacology. 2019;156:107396.

Fox MD. Mapping symptoms to brain networks with the human connectome. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2237–45.

Mo F, Zhao H, Li Y, Cai H, Song Y, Wang R, et al. Network localization of state and trait of auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2024;50:1326–36.

Zhang X, Xu R, Ma H, Qian Y, Zhu J. Brain structural and functional damage network localization of suicide. Biol Psychiatry. 2024;95:1091–9.

Cheng Y, Cai H, Liu S, Yang Y, Pan S, Zhang Y, et al. Brain network localization of gray matter atrophy and neurocognitive and social cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2025;97:148–56.

Zuo X-N, Anderson JS, Bellec P, Birn RM, Biswal BB, Blautzik J, et al. An open science resource for establishing reliability and reproducibility in functional connectomics. Scientific Data. 2014;1:140049.

Yan C-G, Wang X-D, Zuo X-N, Zang Y-F. DPABI: data processing & analysis for (Resting-State) brain imaging. Neuroinformatics. 2016;14:339–51.

Wang Y-W, Chen X, Yan C-G. Comprehensive evaluation of harmonization on functional brain imaging for multisite data-fusion. NeuroImage. 2023;274:120089.

Shirer WR, Ryali S, Rykhlevskaia E, Menon V, Greicius MD. Decoding subject-driven cognitive states with whole-brain connectivity patterns. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22:158–65.

Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hebert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and function of the human insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;34:300–6.

Puiu AA, Wudarczyk O, Goerlich KS, Votinov M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Turetsky B, et al. Impulsive aggression and response inhibition in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and disruptive behavioral disorders: findings from a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;90:231–46.

Craig AD. How do you feel-now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:59–70.

Emmerling F, Schuhmann T, Lobbestael J, Arntz A, Brugman S, Sack AT. The role of the insular cortex in retaliation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152000.

Pugnaghi M, Meletti S, Castana L, Francione S, Nobili L, Mai R, et al. Features of somatosensory manifestations induced by intracranial electrical stimulations of the human insula. Clin Neurophysiol. 2011;122:2049–58.

Whyte CJ, Redinbaugh MJ, Shine JM, Saalmann YB. Thalamic contributions to the state and contents of consciousness. Neuron. 2024;112:1611–25.

Bell C, Rokicki J, Tesli N, Gurholt TP, Hjell G, Fischer-Vieler T, et al. Hypothalamic subunit volumes and relations to violence and psychopathy in male offenders with or without a psychotic disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-023-01725-4.

Yao YJ, Chen Y, Li C-SR. Hypothalamic resting-state functional connectivity and self-evaluated aggression in young adults. Journal Psychiatr Res. 2025;182:421–9.

Bandler RJ. Direct chemical stimulation of the thalamus: effects on aggressive behavior in the rat. Brain Res. 1971;26:81–93.

Mai JK, Majtanik M. Toward a common terminology for the thalamus. Front Neuroanat. 2019;12:114.

Otis JM, Zhu M, Namboodiri VMK, Cook CA, Kosyk O, Matan AM, et al. Paraventricular thalamus projection neurons integrate cortical and hypothalamic signals for Cue-reward processing. Neuron. 2019;103:423–431.e424.

Vertes RP, Linley SB, Rojas AKP. Structural and functional organization of the midline and intralaminar nuclei of the thalamus. Front Behav Neurosci. 2022;16:964644.

Bandler RJ, Flynn JP. Neural pathways from thalamus associated with regulation of aggressive behavior. Science. 1974;183:96–99.

Ferreira A, Dahlöf L-G, Hansen S. Olfactory mechanisms in the control of maternal aggression, appetite, and fearfulness: effects of lesions to olfactory receptors, mediodorsal thalamic nucleus, and insular prefrontal cortex. Behavioral Neurosci. 1987;101:709–17.

Andy OJ, Giurintano L, Giukintano S, McDonald T. Thalamic modulation of aggression. Pavlov J Biol Sci. 1975;10:85–101.

Bostan AC, Dum RP, Strick PL. Cerebellar networks with the cerebral cortex and basal ganglia. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:241–54.

Draganski B, Kherif F, Kloppel S, Cook PA, Alexander DC, Parker GJ, et al. Evidence for segregated and integrative connectivity patterns in the human Basal Ganglia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7143–52.

Averbeck BB, Lehman J, Jacobson M, Haber SN. Estimates of projection overlap and zones of convergence within frontal-striatal circuits. J Neurosci. 2014;34:9497–505.

Chu J, Zheng K, Yi J. Aggression in borderline personality disorder: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2022;113:110472.

Rosell DR, Siever LJ. The neurobiology of aggression and violence. CNS Spectr. 2015;20:254–79.

Kolla NJ, Tully J, Bertsch K. Neural correlates of aggression in personality disorders from the perspective of DSM-5 maladaptive traits: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:330.

Crockett MJ, Apergis-Schoute A, Herrmann B, Lieberman MD, Muller U, Robbins TW, et al. Serotonin modulates striatal responses to fairness and retaliation in humans. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3505–13.

Pais ML, Martins J, Castelo-Branco M, Goncalves J. Sex differences in tryptophan metabolism: a systematic review focused on neuropsychiatric disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:6010.

Godar SC, Fite PJ, McFarlin KM, Bortolato M. The role of monoamine oxidase A in aggression: current translational developments and future challenges. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;69:90–100.

Feng C, Eickhoff SB, Li T, Wang L, Becker B, Camilleri JA, et al. Common brain networks underlying human social interactions: evidence from large-scale neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;126:289–303.

Luo Y, Eickhoff SB, Hetu S, Feng C. Social comparison in the brain: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of functional brain imaging studies on the downward and upward comparisons. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39:440–58.

Gu R, Huang W, Camilleri J, Xu P, Wei P, Eickhoff SB, et al. Love is analogous to money in human brain: coordinate-based and functional connectivity meta-analyses of social and monetary reward anticipation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;100:108–28.

O’Reilly K, Donohoe G, Coyle C, O’Sullivan D, Rowe A, Losty M, et al. Prospective cohort study of the relationship between neuro-cognition, social cognition and violence in forensic patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:155.

Jones MT, Harvey PD. Neurocognition and social cognition training as treatments for violence and aggression in people with severe mental illness. CNS Spectr. 2020;25:145–53.

Manca R, Mitolo M, Wilkinson ID, Paling D, Sharrack B, Venneri A. A network-based cognitive training induces cognitive improvements and neuroplastic changes in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: an exploratory case-control study. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16:1111–20.

Pappa K, Biswas V, Flegal KE, Evans JJ, Baylan S. Working memory updating training promotes plasticity & behavioural gains: a systematic review & meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;118:209–35.

Honey CJ, Kotter R, Breakspear M, Sporns O. Network structure of cerebral cortex shapes functional connectivity on multiple time scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10240–5.

Honey CJ, Sporns O, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Thiran JP, Meuli R, et al. Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2035–40.

Rehman A, Al Khalili Y Neuroanatomy, occipital lobe. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls; 2024.

Tao D, He Z, Lin Y, Liu C, Tao Q. Where does fear originate in the brain? A coordinate-based meta-analysis of explicit and implicit fear processing. Neuroimage. 2021;227:117686.

Gan X, Zhou X, Li J, Jiao G, Jiang X, Biswal B, et al. Common and distinct neurofunctional representations of core and social disgust in the brain: coordinate-based and network meta-analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;135:104553.

Bjorkqvist K. Gender differences in aggression. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;19:39–42.

Rosvall KA, Bergeon Burns CM, Barske J, Goodson JL, Schlinger BA, Sengelaub DR, et al. Neural sensitivity to sex steroids predicts individual differences in aggression: implications for behavioural evolution. Proc Biol Sci. 2012;279:3547–55.

Brouillard A, Davignon LM, Turcotte AM, Marin MF. Morphologic alterations of the fear circuitry: the role of sex hormones and oral contraceptives. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1228504.

Repple J, Habel U, Wagels L, Pawliczek CM, Schneider F, Kohn N. Sex differences in the neural correlates of aggression. Brain Struct Funct. 2018;223:4115–24.

Marrocco J, McEwen BS. Sex in the brain: hormones and sex differences. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18:373–83.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 82171508 and 82071507).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZBC and YDD participated in methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and manuscript writing. YL and BL were engaged in data curation. WBG was involved in methodology, data curation, manuscript review, and funding acquisition. All authors had complete access to the study data and shared final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical University. All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Ding, Y., Liu, Y. et al. Brain network localization of structural and functional abnormality associated with aggression. Transl Psychiatry 15, 400 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03632-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03632-9