Abstract

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has been suggested to be a safe and effective therapeutic option for drug addiction. Although sustained abstinence is better predicted by at least 5 years of drug-free duration, few studies have followed DBS-treated addicted individuals for more than 5 years. Twenty patients with treatment-resistant heroin addiction were enrolled in this prospective, single-center, open-label pilot study. Patients who received DBS of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) with or without the anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC) were followed up for over 5 years, and continuous abstinence, heroin craving (HC), psychometric instrument scores and late positive potential (LPP) amplitudes served as the outcome parameters. Twelve patients maintained sustained abstinence for five years after DBS treatment, and no severe complications or adverse events occurred. A linear mixed-effects model revealed a significant main effect of postsurgical time and relapse status on HC visual analog scale (HC-VAS), SF-36, SCL-90, HAMD, and Y-BOCS scores. Preoperative marital status, HAMD cognitive and SCL-90 psychoticism subscores significantly differed between abstinent and relapsed patients, and persistent abstinence was correlated with moderate acute (VAS 5–8) and delayed (VAS 4–6) psychopsychiatric responses to stimulation. ERP analysis revealed a significant decrease in the drug-pleasant LPP amplitude (400–1000 ms) from baseline to 2–3 years after surgery. The present study suggested that DBS of the NAc/ALIC is effective for reducing heroin craving and preventing relapse in the long term and may reverse motivational attentional bias from drug-related stimuli to pleasant stimuli for heroin-addicted individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Drug addiction continues to be massive public health concerns worldwide. Opioids cause the highest levels of health harm related to deaths and disability adjusted life years (DALYs) of all drug groups [1], and approximately 60 million people use opioids worldwide in 2022 [2]. The number of registered heroin users was 305000 in China in 2023 [3] and 261,000 in England in 2019/2020 [4]. In the US, 81,806 deaths from drug overdose involving opioids occurred in 2022 [5]. Opioid addiction is also associated with morbidity and mortality from HIV and hepatitis and can lead to criminal activity. The average annual societal cost of an individual with heroin addiction in the UK was reported to be approximately £58,000 in 2021 [6]. In 2020 alone, the opioid epidemic cost the US economy an estimated $1.5 trillion [7].

Treatments for opioid addiction include pharmacotherapies and psychosocial approaches, and medication for opioid use disorders (MOUD) is still the gold standard treatment [8]. Compared with other medications, methadone leads to relatively greater retention in treatment (47% at 12 months according to the systemic review) [9, 10], and methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) remains the recommended first-line MOUD, showing great effectiveness in reducing illicit opioid use and its associated negative outcomes [8]. However, achieving long-term abstinence is still a challenge for MOUDs [9, 10]. One randomized control trial (RCT) in the US reported that the illicit heroin use rate was greater than 50% at 12 months after the standard MMT [11], and the rate of abstinence from street heroin was 4% during weeks 14–26 after the oral MMT in another RCT in England [12].

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has emerged as a promising treatment approach for refractory psychiatric disorders, including drug addiction, because of its advantages of reversibility and controllability [13]. As a key component of the reward circuit and the functional interface between the limbic and motor systems, the nucleus accumbens (NAc) plays a key role in the pathogenesis of drug addiction and therefore has been used as a main target in DBS treatment of addiction [13]. Since Kuhn et al. first reported that DBS of the NAc (NAc-DBS) markedly alleviated comorbid alcohol dependency in one patient with severe anxiety disorder in 2007 [14], studies in which DBS was used to treat addiction caused by the use of alcohol, heroin, amphetamine, cocaine and nicotine have been published [15]. Most studies have suggested that NAc-DBS is a safe and effective therapeutic option for addiction, with full relapse and abstinence rates of 23.9% and 26.8%, respectively, according to one recent systematic review [16]. However, these studies were all observational studies with small sample sizes [15, 16], except one recently reported double-blind randomized controlled multicenter trial on NAc-DBS in patients with treatment-resistant alcohol use disorder [17].

With regard to heroin addiction, after the first case published in 2011 reported that one patient remained abstinent from heroin for more than six years after the initiation of NAc-DBS [18], another 21 heroin-addicted individuals were reported to receive DBS treatment in the following eight studies that have been published [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Among these 21 patients, 9 remained abstinent during the follow-up, with the follow-up periods ranging from 6 months to 40 months. However, several studies have suggested that sustained abstinence is better predicted by a drug-free duration of at least five years [27, 28], and all these studies were case reports or case series with a sample size of eight or less; in this context, to assess the efficiency of DBS therapy for heroin addiction is still difficult.

The present study completed an over-five-year follow-up for 20 heroin-addicted individuals treated with DBS. We completed an overall evaluation of sustained abstinence outcomes, stimulation effects and long-term changes in neuropsychiatric status in this cohort and further analyzed the factors predicting long-term relapse prevention outcomes. Additionally, one component of event-related potentials (ERPs), the late positive potential (LPP), which is an objective and temporally precise marker of motivated attention to salient stimuli [29, 30], was extracted from electroencephalograms (EEGs) and used to measure longitudinal changes in the motivational salience of heroin-related stimuli in addicted individuals following NAc-DBS therapy.

Patients and methods

Study population and design

In addition to the 12 patients reported by our team previously [20, 22, 24], another 8 patients underwent bilateral DBS of the NAc and anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC) according to a previously published protocol [24]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosed with heroin addiction according to the DSM-V criteria; 18–50 years of age; abused heroin for 3 years or more; relapsed at least 3 times after previous conservative treatment, including MMT; and had reliable support from family members. The exclusion criteria were as follows: severe cognitive disorders, acute psychosis and/or other severe mental disorders such as schizophrenia or dementia, previous neurosurgical procedures or ablative therapy, and/or any contraindication to surgery. This single-center, prospective, open-label pilot study has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01274988). All methods and procedures employed were in strict accordance with the ethical guidelines of the relevant national and institutional committees governing human experimentation, and we adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of TangDu Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, China. All patients were recruited voluntarily and independently signed informed consent forms, and their general characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Surgery and programming

All patients completed physiological detoxification and had negative urine analysis and naloxone challenge test results before surgery. The details of the surgical procedures and the verification of the individualized surgical stereotactic coordinates for patients are listed in Supplementary Methods 1 and 2. Programming was initiated approximately two to three weeks after electrode implantation. Stimulation of each contact was conducted first to observe the acute stimulating effect, and the contacts were not activated if the stimulation induced negative psychopsychiatric responses such as anxiety and phobia. Then, stimulation parameter optimization was performed using the method described in our previous publication [24], with the aim of producing anti-craving effects with minimal adverse side effects.

Follow-up and assessment

The primary outcome was the duration of abstinence after surgery, and the abstinence status of the patients was monitored by urine analysis and family reports. Telephone interviews with family members and patients were conducted once per month within the first 2 years and once every 3 months within the 2 to 5-year period to determine the abstinence status and general condition of the patients. In addition, the patients underwent urine tests at 3, 6, 12, 24 months and 5 years after surgery, as well as 3 randomly assigned tests within the first 2-year period; at these visits, the patients underwent face-to-face interviews.

The secondary outcome measures included abstinence rates at 5 years after surgery. Heroin craving (HC) was self-reported using a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) and psychometric instruments, including the Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90), Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), and 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), as well as the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ) and Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS), were administered to patients at baseline and at various time points after surgery (Supplementary Methods 3.1–3.8).

Measurement of the NAc volume, localization of DBS electrodes/contacts, and estimation of the local volume of tissue activated (VTA)

The measurement of the NAc volume was conducted by FSL tool according to the method described by previous report [31], with details shown in Supplementary Method 4. The locations of DBS electrodes and contacts were verified using the pipeline in the Lead-DBS MATLAB toolbox [32, 33] (Horn & Kühn 2017; RRID: SCR_002915; https://www.lead-dbs.org), for which coregistration between the postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/computed tomography (CT) images and the preoperative MR images was performed. The details of this pipeline and the group distribution of DBS electrodes and contacts for all patients are described in Supplementary Method 5.

The estimations of the local VTAs were conducted by tools implemented in Lead-DBS v2.6. The VTA was modeled and estimated based on the patients’ final stable DBS programming parameters, and the SimBio/Fieldtrip model in Lead-DBS was used to calculate the VTA (Supplementary Method 6). The three-dimensional visualization was performed in 3D Slicer by integrating VTA results with nucleus accumbens atlas of core and shell subregions.

Probabilistic stimulation atlases (PSAs)

Individual structural MR images of each patient were coaligned with a 100 × 50 × 80 mm MNI standard space with an isotropic voxel of 0.1 mm. Nuclei near the NAc and ALIC were automatically segmented and labeled. Probabilistic stimulation atlases (PSAs) were generated by analyzing the VTA and electric field distributions from 20 patients following the methodology detailed in Supplementary Method 7, enabling systematic evaluation of stimulation efficacy across distinct neuroanatomical regions.

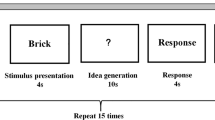

Procedures for studying event-related potentials

ERPs were recorded as patients passively viewed four categories of images (30 images in each picture category, each viewed for 2000 ms). Three image types were selected from the Chinese Affective Picture System (CAPS) [34], including 30 pleasant, 30 unpleasant and 30 neutral pictures. The fourth picture category (30 pictures) depicted drugs and individuals preparing, using or simulating the use of heroin, as previously described [29, 30]. The ERPs were then constructed by separately averaging trials based on picture type: pleasant, unpleasant, neutral and heroin-related pictures [29, 30, 35]. The newly created differential scores are referred to as pleasant-neutral, drug-neutral and drug-pleasant, respectively [35]. The details of the normative valence and arousal ratings of the affective images and the steps involved in EEG signal acquisition and processing are described in Supplementary Methods 8 and 9.1–9.3.

Statistical analysis

For comparison of continuous variables between abstinent and relapsed patients, the normality of the distribution of the samples was determined by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For the samples with a non-normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparison. For the samples with a normal distribution, Levene’s-test for homogeneity of variance between the two groups was conducted; the independent samples t-test was used for equal variances, while Welch’s adjusted t-test was used for unequal variances. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for paired comparison for the variables with non-normal distribution. The Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the categorical variables between the two groups because the small total sample size in this cohort. The linear mixed-effects model (LMM) was constructed to account for both fixed and random effects, ensuring a robust analysis of the longitudinal data, so we applied LMM to analyze the longitudinal outcome variables including instrument scores (for patients 3–7 and 9–20) and LPP substrate amplitudes (for patients 11–20), for which the model included fixed effects for relapse status and time (different time points [TPs], defined in Supplementary Methods 3.8 and 9.3) and a random effect of patient ID. The baseline and all follow-up measurements for a patient were fitted using maximum likelihood methods with an unstructured covariance matrix. Post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni’s correction were conducted after linear mixed-effects model analysis for multiple comparisons. The interactions between time and relapse status were tested. The repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) can account for the repeated measurements taken from the same individuals under different conditions, so we used this method to analyze the preoperative LPP amplitudes for patients 11–20, with picture type (pleasant, neutral or heroin-related) as the within-group factor. Repeated-measures ANOVA was also used to analyze the postoperative LPP amplitudes for 16 patients who completed the ERP recording at postoperative 2 to 5 years (patients 3–6 and 9–20) as well, with picture type as the within-group factor and abstinence status (11 abstinent and 5 relapsed) as the between-group factor. The Bonferroni correction method was used to make multiple comparisons for LPP amplitudes among each picture type. All tests were two-sided, and all the significance thresholds were set at P < 0.05. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 software.

Results

Study cohort

The baseline characteristics of all 20 individuals with heroin addiction included in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1, with a mean (SD, range) heroin abuse duration of 9.55 (6.03, 3.00–25.00) years and a mean daily heroin abuse dosage of 0.48 (0.15, 0.20–0.90) g. The patients received various treatments (compulsive detoxification, methadone substitution, subcutaneous and oral administration of naltrexone), but all the treatments failed because of repeated relapses (7.00 ± 2.13 times). The postoperative MR/CT images for all patients are shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Effects of stimulation and the current status of the DBS devices

As shown in Supplementary Table 2, some patients reported acute immediate responses during the initial stimulation test period, and the most frequently reported feelings included improved mood and increased energy. The locations of the electrodes and contacts varied across all patients (Fig. 1A), and the active contacts (stimulation induced positive psychopsychiatric effects) and the inactive contacts (stimulation had no effects) were represented in the same cohort atlas space, showing that they intersect with each other (Fig. 1B and C).

A Group distribution of DBS electrodes on all 40 sides in the 20 patients in the coronal view. The shell and core regions of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) are represented in dark blue and light blue, respectively. B and C Group distribution of contacts for which stimulation induced positive psychopsychiatric responses (red dots) and for which stimulation had no effect (blue dots) by 3-D visualization, in the coronal view from the anterior side (B) and in the sagittal view from the right side (C). D Proportion of abstinent patients followed up at different time points after surgery. Red line: Patients who have remained abstinent since the surgery. Blue line: Patients who have remained abstinent since the surgery plus two patients who ultimately achieved long-term abstinence after modification of the stimulation parameters. NAc, nucleus accumbens; Ca, caudate; Pu, putamen; GPe, external globus pallidus; GPi, internal globus pallidus. For A and B: R, right side; L, left side; For C: A, anterior side; P, posterior side.

When chronic stimulation was initiated (the final stimulation parameters are shown in Supplementary Table 3), 11 patients (patients 3-6,9-13,16,18) reported significant acute responses (increased energy, better mood, hypomania, talkativeness and smiling were most frequently reported, as shown in Supplementary Table 4), most of which were strong within the initial 2–3 days. These responses gradually declined during the initial 7–10 days for most patients, whereas for some other patients, the stimulation parameters needed to be modified for the treatment to be tolerable. Patient 19 reported a weak immediate feeling of a better mood and increased energy, which lasted for only 3 days. For 4 patients (patients 1, 15, 17, and 20) in whom acute responses were absent, a delayed moderate effect (self-reported VAS scores of 4–6) was reported at approximately 2 to 3 months after surgery, with the most frequently reported feelings including better mood, decreased drug craving and a gentler mental state and temper. The remaining 4 patients (Patients 2, 7, 8, and 14) reported no (self-reported VAS score of 0) or little (self-reported VAS score of 1 or 2) acute or delayed response.

Depletion of the battery of the implantable pulse generator (IPG) was confirmed for 15 patients who used nonrechargeable devices and 1 patient who used rechargeable device (unworked due to stopping the recharging), among whom 6 patients underwent removal of the entire DBS device or only IPGs, and the stimulation was inactive for all other 10 patients, although the devices were retained in their bodies (Supplementary Table 3). The entire DBS device including the rechargeable IPG for patient 13 was removed according to the patient’s requirement due to unsatisfied relapsed outcome, and the rechargeable IPGs for patients 17 and 18 continued to work until recently (Supplementary Result 1, Supplementary Table 3).

Abstinence or relapse outcomes

As shown in Table 1, 10 patients (10/20 = 50%) remained abstinent for more than 5 years after surgery, with the maximal abstinence period reaching 13 years (Fig. 1D). Although patients 17 and 18 relapsed within one year after surgery, they finally achieved persistent abstinence (93 and 77 months) after modification of the stimulation parameters (Supplementary Result 1; Supplementary Table 5), and the remaining patients were defined as relapse or failure (Supplementary Result 2).

Factors associated with abstinence or relapse

Baseline characteristics and anatomical features of the NAc

Among the preoperative characteristics (Supplementary Table 6), only marital status (P = 0.045 by Fisher’s exact test) significantly differed between the patients who obtained the sustained abstinence (absolute abstinence, n = 10) and the other patients (n = 10). Patients with absolute abstinence had lower HAMD cognitive subscores (0.26 ± 0.22 vs. 0.59 ± 0.30, t = −2.675, P = 0.017) and lower SCL-90 psychoticism subscores (1.34 ± 0.22 vs. 1.72 ± 0.35, t = −2.711, P = 0.015).

The volume of the bilateral NAc for all patients is listed in Supplementary Table 7, indicating significant asymmetry between the left (580.75 ± 109.64 mm3) and right NAc (498.02 ± 81.43 mm3). A comparison of the NAc size between the absolutely abstinent patients and the other patients indicated that neither the volume of the right or left NAc nor the ratio of the volume of the right to left NAc correlated with the relapse outcome of the patients (Supplementary Table 8).

Stereotactic coordinates for lead placement

The stereotactic coordinates for lead placement in anterior commissure-posterior commissure (AC-PC) system for all patients are listed in Supplementary Table 9. For all three-dimensional individualized stereotactic coordinates of the bilateral NAc and the stereotactic horizontal and vertical angles of bilateral lead placement in AC-PC system, no significant differences were found between the absolutely abstinent patients and the other patients (Supplementary Table 8), and the results were the same as the normalized stereotactic coordinates of the bilateral NAc in MNI space (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11).

Device vendors/lead configurations, contact activating settings and locations

As shown in Supplementary Tables 3 and 12, the patients received implantation of DBS devices from three vendors, with four different lead configurations. There was no significant difference in the relapsed outcomes, craving reductions, or side effects between the four different lead configurations (Supplementary Table 12), and the multiple pairwise comparisons also showed no significant difference (data not shown). As shown in Supplementary Table 13, there was no significant difference in the relapsed outcomes between three different contact-activating settings, or between three different settings for stimulation frequency, and the multiple pairwise comparisons also showed no significant difference (data not shown). The contact locations for the patients who maintained sustained abstinence and those for the other patients were represented in the same cohort atlas space and visualized relative to the segmentation of the targeted nuclei (Supplementary Figure 2). No distinct location preference was detected for the active contacts between the two groups of patients, with the locations intersecting with each other.

Volume of tissue activated (VTA)

Patient-specific modeling of VTA (shown in Supplementary Figure 3) in the present study involved the impact of variation in DBS device vendors, lead configurations, the location of activated contacts, and stimulation parameters including voltage and pulse width. The VTA of each patient was shown in Supplementary Figure 4, and these VTAs exhibited large regions of overlap (NAc, middle and ventral ALIC, ventrolateral caudate, internal globus pallidus (GPi), external globus pallidus (GPe), and medial putamen, from y = +12.9 to +25.3 mm along the anterior-posterior direction with the midcommissural point (MCP) as the reference point, shown in Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2B, there was also a large overlap of VTAs between the patients who maintained sustained abstinence and the remaining patients, and comparisons of the overlapping VTAs with different targeted nuclei between these two groups of patients are shown in Supplementary Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 14, with no significant difference detected.

A PSA of the proportion of the total number of patients stimulated at each voxel; B Regions stimulated in abstinent patients, relapsed patients and the regions where they overlapped. C PSA of mean relapse prevention index (RPI) score (for voxels with VTA counts greater than 10), where the value of each voxel represents the average RPI score of VTAs produced at that voxel; D PSA of the mean E-field value for 20 patients, where the value of each voxel represents the average E-field intensity across the 20 patients at that voxel. E PSA of the mean E-field value for 12 abstinent patients, where the value of each voxel represents the average E-field intensity across the 12 abstinent patients at that voxel. F PSA of the mean E-field value for 8 relapsed patients, where the value of each voxel represents the average E-field intensity across the 8 relapsed patients at that voxel. The number in the upper left corner of each panel represents the AC-PC coordinates (MCP as the reference) of the coronal plane in which it is located. R, right side; L, left side; PSA, probabilistic stimulation atlas.

By averaging the relapse prevention index (RPI) for each isotropic voxel of the VTA among all patients (Fig. 2C), the results revealed stimulating adjunct region between the ventral ALIC and the dorsal NAc (V-ALIC/D-NAc, from y = +14.7 to +22.9 mm along the anterior-posterior direction with the MCP as the reference) obtained a higher mean RPI, whereas the PSA of the electric field value (indicating the stimulating intensity) among all patients indicated that this region was the most frequently stimulated with greater intensity (Fig. 2D). The PSAs of the electric field values for abstinent and relapsed patients are shown in Fig. 2E and F, indicating that abstinent patients have greater mean electric field values for stimulation in the V-ALIC/D-NAc, whereas the relapsed patients have greater mean electric field values for stimulation in the region which was slightly lateral and dorsal to the V-ALIC/D-NAc.

Stimulation effects according to patients’ self-reports

As shown in Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table 4, the patients who reported no or few positive psychopsychiatric responses (self-reported VAS scores of 0–2) after stimulation ultimately relapsed. The patients who reported very intense acute psychopsychiatric responses (self-reported VAS scores ranging from 8–10) after stimulation also relapsed soon after surgery (Fig. 3A). Persistent abstinence was observed in individuals who reported moderate acute psychopsychiatric responses (self-reported VAS scores of 5–8) immediately after stimulation, as well as individuals who manifested delayed moderate responses (self-reported VAS scores of 4–6) after stimulation (Fig. 3A).

A Relationship between abstinence outcomes and the intensity and starting time point of the main positive psychopsychiatric responses (scaled by VAS scores) for each individual after the stimulation on. Red dots indicate patients who experienced relapse. Green dots indicate patients who remained abstinent throughout the study. # indicates the patients who initially relapsed (red dots) and ultimately achieved long-term persistent abstinence (green/black mixed dots) after the modification of the stimulation parameters. Stim-on: stimulation on; wks: weeks; no-resp: no response. B–F The heroin-craving (HC)-VAS (B), SF-36 (C), SCL-90 (D), HAMD (E) and Y-BOCS (F) for patients 3–7 and 9–20 at baseline and at 6, 12, and 24 months and 5 years after surgery. The purple dots indicate patients who were using drugs at the time of the interview. The black dots indicate patients who were abstinent (drug free) at the time of the interview.

Changes in neuropsychological status, general sociofamily conditions and quality of life

No severe complications or adverse events occurred. Most patients exhibited significant improvement in interconnections with family and society (including finding new jobs and improving marital status), more frequent sexual activity and better appetite with increased body weight (Table 1; Supplementary Result 1). Interestingly, five patients reported significantly increased amounts of alcohol consumption (liquor and beer), and seven patients reported significantly decreased smoking after DBS therapy.

The distributions and changes in the scores of the HC-VAS, quality of life scale (SF-36) and several neuropsychological instruments (SCL-90, HAMD, Y-BOCS) are displayed in Fig. 3B–F and Supplementary Figure 6, respectively. The linear mixed-effects model revealed a significant effect of time on the HC-VAS, SF-36, SCL-90, HAMD and Y-BOCS scores (P < 0.001; Supplementary Table 15). There was a significant effect of relapse status on the HC-VAS (β = 5.19, SE = 0.34, P < 0.001), SF-36 (β = −32.16, SE = 3.92, P < 0.001), SCL-90 (β = 0.60, SE = 0.10, P < 0.001), HAMD (β = 9.90, SE = 1.59, P < 0.001) and Y-BOCS (β = 15.91, SE = 1.80, P < 0.001) scores. The distributions and changes in the 4 subscores of the EPQ and WMS-MQ scores are displayed in Supplementary Figure 7. The linear mixed-effects model (Supplementary Table 15) revealed a significant decrease in the EPQ-N subscore from TP0 to TP2 (β = −10.39, SE = 3.53, P = 0.005) and from TP0 to TP3 (β = −10.39, SE = 3.53, P = 0.005) and a significant decrease in the EPQ-P subscore from TP0 to TP2 (β = −4.10, SE = 1.91, P = 0.036). A significant main effect of relapse status was detected for the EPQ-N subscore only (β = 13.71, SE = 3.90, P = 0.001). No significant mean effect of time on WMS-MQ was detected, except for a significant increase from TP0 to TP1 (β = 9.06, SE = 4.26, P = 0.037), and there was no significant main effect of relapse status on the WMS-MQ score (Supplementary Table 15). There were no significant effects of the relapse status×time interaction on any of the abovementioned scores.

Changes in the motivational salience of heroin cues according to ERPs

The linear mixed-effects model was applied to detect the longitudinal changes of various LPP scores from baseline to post-operation for patients 11–20 (Fig. 4A1–A3 and Table 2). There was no significant main effect of time on the pleasant-neutral LPP for any time window (400–1000 ms, 1000–2000 ms and 400–2000 ms), whereas a trend toward a significant main effect of relapse status was detected for the pleasant-neutral 1000–2000 ms LPP (β = −2.10, SE = 1.07, P = 0.060). There was a significant decrease from TP1 to TP2 (β = –2.54, SE = 0.70, P = 0.005) and a trend toward a significant decrease from TP0 to TP2 (β = –1.41, SE = 0.74, P = 0.069) in the drug-neutral 400–1000 ms LPP and a trend toward a significant decrease from TP1 to TP2 in the drug-neutral 400–2000 ms LPP (β = −2.33, SE = 0.95, P = 0.069), whereas no main effect of time was detected in the drug-neutral 1000–2000 ms LPP. There was a significant decrease from TP0 to TP2 (β = −2.20, SE = 0.77, P = 0.008) and a significant decrease from TP1 to TP2 (β = −2.44, SE = 0.74, P = 0.007) in the drug-pleasant 400–1000 ms LPP, but no main effect of time was detected in the drug-pleasant 400–2000 ms LPP or 1000–2000 ms LPP. There was no main effect of relapse status on drug-neutral or drug-pleasant LPPs in any of the time windows and no significant effects of the relapse status×time interaction on any of the LPP scores for any time window.

A Grand averaged event-related potential (ERP) waveforms at the centroparietal (Cz, FCz, FC1, FC2 and Fz) electrodes for pleasant (orange line), neutral (gray line) and heroin-related (blue line) pictures for patients 11–20 at TP0 (baseline, in A1), TP1 (6 months to 18 months after surgery, in A2) and TP2 (2 to 3 years after surgery, in A3). B Grand averaged event-related potential (ERP) waveforms at the centroparietal (Cz, FCz, FC1, FC2 and Fz) electrodes for pleasant (orange line), neutral (gray line) and heroin-related (blue line) pictures for all 16 patients (patients 3–6 and 9–20, in B1), 11 abstinent patients (B2), and 5 relapsed patients (B3) who completed the LPP recording at the final follow-up time point (2 to 5 years after surgery). post-op, postoperative; yrs, years.

The repeated-measures ANOVA was applied to detect the influence of the different types of pictures on LPP scores (Fig. 4B1–B3 and Supplementary Table 16). Before surgery, there was a significant main effect of picture type on 400–2000 ms LPP amplitudes (F = 7.287, P = 0.005) for patients 11–20 (all these patients with detoxification status), and further pairwise comparisons revealed a significant difference in LPP amplitude between heroin-related and neutral pictures (d = 1.836, 95% CL: 0.568 to 3.104, P = 0.006). After surgery, there was no significant main effect of picture type (F = 1.223, P = 0.310) or abstinence status (F = 2.382, P = 0.145) on 400–2000 ms LPP amplitudes for all 16 patients who completed the LPP recording at 2 to 5 years after surgery (11 abstinent and 5 relapsed). Further pairwise comparisons revealed no significant difference in LPP amplitude between heroin-related and neutral pictures (d = 0.740, 95% CL: −0.775 to 2.255, P = 0.617).

Discussion

The sample size for this prospective pilot study was larger than those in previously published studies, and all patients completed more than 5 years of follow-up. The percentage of patients abstinent for more than five years in this cohort was 60%, indicating that DBS of the NAc or NAc/ALIC is a promising method for preventing relapse after detoxification in individuals with heroin addiction.

Owing to the heterogeneity of outcomes for individuals in the present study, it is necessary to define the optimal indicators for the results of NAc/ALIC DBS therapy for treating heroin addiction. Our study revealed that being married and having lower HAMD cognitive and SCL-90 psychoticism subscores were associated with better abstinence outcomes, indicating that patients with no or milder neuropsychiatric comorbidities and better family support may benefit more from DBS therapy. These findings also support the biopsychosocial model for addiction treatment [36].

This study suggested that the NAc is an effective target for addiction treatment, which is in line with previous studies [24, 26]. However, both the comparisons of the overlapping VTAs with either the NAc core or shell and the comparison of stereotactic coordinates for lead placement revealed no significant differences between abstinent and relapsed patients. Therefore, our analysis could not confirm the optimal stimulation subregions in the NAc with respect to long-term efficacy in preventing relapse. One explanation is the synergy between the NAc core and shell in the pathogenesis of drug addiction [37, 38]; thus, there is still controversy regarding the efficacy of NAc core versus shell stimulation for addiction treatment [39, 40]. In addition, the following limitation also make defining a “sweet” subregion in the NAc challenging: first, the present small sample-size study did not include sufficient variability in electrode placement or stimulation parameters (voltage, frequency, and pulse width) to distinguish subtle differences in efficacy between subregions, which led to a significant overlap of VTAs among all patients in our cohort; second, the VTA models may approximate the real volume of tissue activated but not fully represent reality, and the estimation of the VTA did not involve the impact of stimulating frequency; third, the use of nonrigid registration to the standard MNI space could have introduced inaccuracies, particularly given that individual anatomical differences in the NAc, and the MNI space may not capture small yet clinically significant variations in targeting, especially in a heterogeneous population of patients with addiction; and finally, patients with addiction often present with anatomical asymmetry in brain structures involved in reward and motivation [41, 42], including the NAc, and our measurement also revealed larger volume of the NAc on the left side for heroin-addicted individuals which was coincide with previous reports [41, 42], this asymmetry in the NAc may have affected the ability to identify clear “sweet” subregions via standard targeting methods.

In the present study, although no significant difference in relapsed outcomes was detected between the different settings of contacts activation for stimulation, i.e., single stimulation of the NAc, combined stimulation of the NAc and ALIC by triple-contact activation and double-contact activation, stimulation of the ALIC in addition to the NAc, which was performed on 18 patients, showed good efficacy, with an abstinence rate of 61.1% (11/18). These results indicate that combined stimulation of the NAc and ALIC is a promising stimulation strategy for DBS treatment of addiction, which is in line with the findings of previous studies [24, 26]. The fibers passing through the ALIC include the supralateral medial forebrain bundle (slMFB), the activation of which is thought to activate the entire mesocorticolimbic system and to have an antidepressant effect during stimulation [43]. Although the NAc is the most common target used in addiction treatment, Levy et al. reported that localized electrical stimulation of the MFB at the lateral hypothalamus and prefrontal cortex reduced cue-induced cocaine-seeking behavior in rats, indicating that intervention in the MFB may also be a strategy for treating addiction [44]. This region may underlie the efficacy of combined stimulation of the NAc and ALIC in relapse prevention observed in the present study.

In our study, the most frequently reported feelings during stimulation included improved mood and increased energy, with some patients exhibiting hypomania and laughter. These stimulation-induced positive psychopsychiatric responses have been reported in our previous reports and other studies that used DBS to treat obsessive‒compulsive disorder (OCD) and depression [24, 45, 46]. Ihtsham et al. reported that intraoperative stimulation-induced laughter may predict the long-term response to DBS in OCD patients [47]. Our studies did not define linear correlations between the strength of stimulation-induced positive psychopsychiatric responses and long-term abstinence outcomes but confirmed that moderate acute or delayed psychopsychiatric responses were predictors of a better abstinence outcome. The tendency to relapse for patients who showed no or mild response to stimulation may be explained by insufficient intervention in the mesocorticolimbic circuit, suggesting that the precise location of active contacts and optimal stimulation parameters to induce proper psychopsychiatric responses are crucial. However, patients who experienced laughter and hypomania tended to relapse, and this finding was puzzling. One possible explanation is that individuals who are sensitive to stimulation are also highly susceptible to relapse. Another explanation is that hypomania may be an emotional cue for relapse for some patients, who reported that the hypomania induced by electrical stimulation resembled the feeling induced by drug abuse.

For the stimulation parameters, our study applied a long pulse width of 180–210 µs and a voltage of 2–4 V, which has been commonly used for DBS treatment for psychiatric disorders, and the present results indicated that this approach is appropriate for addiction treatment as well. Positive linear correlations between the amplitude of voltage and the strength of the psychopsychiatric response have been reported previously, and stimulation with a 2–5 V voltage has been well established to be of the proper power for the treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases [46]. The advantage of longer pulse width stimulation has been reported to be associated with greater current density, increased spatial distribution of the electric field, or possibly activation of smaller unmyelinated fibers in addition to larger myelinated fibers [48, 49]; thus, most previous studies have used a long pulse width for DBS treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases [15, 45]. However, one recent study indicated that long (210–450 µs) and short (90 µs) pulse widths were equally effective in reducing depressive symptoms in patients receiving subcallosal cingulate DBS to treat treatment-resistant depression [50]. Although there is no consensus regarding the optimal pulse width, the synchronized titration of voltage and pulse width may be crucial for achieving the best clinical efficacy and minimal adverse effects. For setting the stimulation frequency, a high frequency (130–165 Hz) was commonly used for DBS treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases in previously published studies [15, 51, 52], although some animal studies have shown that stimulation at a low frequency is also effective [53]. The reason for this discrepancy was attributed to the fact that the mechanism by which DBS treats addiction is still unclear.

Craving is considered a key contributing factor to relapse [36], and the patients in the present study reported a significant decrease in craving following chronic NAc/ALIC stimulation. One recent systematic review indicated that DBS intervention presented encouraging levels of efficacy in reducing cravings for individuals with substance use disorders, which may be the reason that addicted individuals achieve long-term abstinence after DBS therapy [16]. However, self-reported craving is not an objective measurement because its reliability could be hampered by impaired insight, which is prevalent in individuals with drug addiction [29]. Craving can be regarded as an abnormal motivational state in which addicted individuals allocate more motivational attention to drug-related stimuli than to neutral stimuli [54]. To quantitatively measure attention to drug-related cues, several prior studies have used the LPP, an ERP component that indicates motivational attention to emotionally salient stimuli, and increased LPP amplitude in response to drug-related cues compared with neutral cues has been consistently shown across most substance use disorders [29, 55].

The present study used linear mixed effect model analysis to study the impact of postsurgical time on drug-neutral LPP amplitudes, and a decreasing trend in LPP amplitude from baseline (TP0) to 2–3 years after surgery (TP2) was detected in the poststimulus 400–1000 ms time window. The lack of abstinence status×time interaction suggested that DBS therapy per se can decrease early attentional bias to heroin-related stimuli for addicted individuals. However, no significant decrease in late LPP amplitude (poststimulus 1000–2000 ms time window) was detected from TP0 to TP2, which may be attributed to the relatively small sample size. Another possibility might be that sustained attentional engagement and encoding of heroin-related stimuli could not be sufficiently interfered with by DBS therapy at 2–3 years after surgery in some patients; thus, one case of relapse (patient 14) occurred over 2 years after surgery.

On the other hand, the present study revealed no significant difference in either early or late drug-neutral LPP amplitudes after approximately 6 months of sustained drug-free duration postoperatively compared with the preoperative baseline values. Parvaz et al. [30] reported that drug-related LPP amplitudes exhibited an inverted “U”-shaped trajectory as a function of the duration of abstinence for cocaine abusers; drug-related LPP amplitudes initially increased from 2 days to 1 week of abstinence, peaked at 1 month to 6 months, and decreased after 1 year of abstinence. Our result was consistent with these studies, suggesting that a duration of NAc/ALIC-DBS from 6 months to 1 year had an insufficient effect on the incubation of cravings in individuals with heroin addiction; thus, most relapses occurred within the first 3–8 months after DBS surgery in the present case series.

Our clinical follow-up revealed significant improvements in appetite and sexual activity in patients after DBS therapy, and we hypothesize that DBS may improve drug use-induced hyposensitivity to natural reinforcers. Although the changes in the pleasant-neutral LPP amplitudes were not significantly different for either TP0-TP1 or TP0-TP2, increasing trends after DBS (400–1000 ms) were suggested by our results. By inspecting drug-pleasant LPP amplitudes, we found a significant decrease in early LPPs at 2–3 years after surgery, suggesting that DBS for more than 2 years can reverse early EEG-indexed attentional bias between drug-related and pleasant stimuli. Our results suggested that attention bias reversal by DBS may be due to a decrease in the drug-related LPP and an increase in the pleasant LPP. Previous animal studies have indicated that NAc-DBS attenuated the reinstatement of cocaine seeking but did not affect the reinstatement of food seeking [56] Our study on addicted individuals provided evidence that long-term chronic DBS may decrease excessive attentional bias toward drugs and simultaneously improve the reward of natural reinforcers.

Limitations

The present study is limited by the small sample size: only 17 patients completed the longitudinal neuropsychiatric assessment, and only 10 patients completed the longitudinal LPP measurement. Because of the lack of a control group and the open-label study design, a placebo effect secondary to the surgical procedure, DBS adjustment, and continuous follow-up cannot be excluded to confirm the accurate efficacy of DBS treatment. The variability introduced by the use of different DBS devices and leads cannot be ignored. However, the small sample size made it difficult to detect the significant impact of variability in DBS device vendors, lead configurations, locations of activate contacts, angles of lead placement and stimulation parameters on the clinical outcomes of patients. In the methodology, nonrigid registration to the MNI space introduces inevitable inaccuracies. The instruments used to assess the impact of DBS are limited in their specificity for heroin-addicted individuals, and more targeted evaluations of how DBS influences patients’ ability to experience pleasure and motivation, e.g., the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS), are needed in future studies. In addition, all patients who underwent surgery were willing and strongly motivated to cease their drug using, which may not accurately represent the overall population of individuals with heroin addiction; thus, the implications of self-selection bias due to participants’ high motivation to abstain reduce the reliability of conclusions regarding the efficacy of DBS. Finally, the optimal stimulation parameters (e.g., low frequency versus high frequency) and modes (e.g., continuous versus intermittent or close-looped stimulation) could not be determined in the present study, and the influence of the various settings for stimulating parameters on clinical outcomes still needs to be investigated in future studies with larger sample sizes and delicate designs.

Data availability

Some of the data are available at ClinicalTrials.gov and https://doi.org/10.17632/y57h5wtnk5.1, and all the detailed data can be shared by contacting the corresponding author.

References

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Miles To Go: Closing Gaps, Breaking Barriers, Righting Injustices; 2018. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents//2018/global-aids-update.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2022: Global Overview Drug Demand Supply; 2022. Available at: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2022.html.

China National Narcotic Control Committee. China Drug Situation Report; 2022. Available at: http://www.nncc626.com/2023-06/21/c_1212236289_3.htm.

Gov.uk. Adult Substance Misuse Treatment Statistics 2019 to 2020: Report; 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/substance-misuse-treatment-for-adults-statistics-2019-to-2020/adult-substance-misuse-treatment-statistics-2019-to-2020-report#Overview.

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. America’s drug overdose epidemic: putting data to action;2022 Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/prescription-drug-overdose/index.html.

Black, DC Review of Drugs - Evidence Relating to Drug Use, Supply and Effects, Including Current Trends and Future Risks. 2021. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/882953/Review_of_Drugs_Evidence_Pack.pdf.

United States Joint Economic Committee. The Economic Toll of the Opioid Crisis Reached Nearly $1.5 Trillion in 2020; 2022. Available at: https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/.

Volkow ND, Blanco C. Fentanyl and other opioid use disorders: treatment and research needs. Am J Psychiatry. 2023;180:410–7.

Degenhardt L, Clark B, Macpherson G, Leppan O, Nielsen S, Zahra E, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and observational studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10:386–402.

Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2004:CD002207.

Sees KL, Delucchi KL, Masson C, Rosen A, Clark HW, Robillard H, et al. Methadone maintenance vs 180-day psychosocially enriched detoxification for treatment of opioid dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1303–10.

Strang J, Metrebian N, Lintzeris N, Potts L, Carnwath T, Mayet S, et al. Supervised injectable heroin or injectable methadone versus optimised oral methadone as treatment for chronic heroin addicts in England after persistent failure in orthodox treatment (RIOTT): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1885–95.

Wang TR, Moosa S, Dallapiazza RF, Elias WJ, Lynch WJ. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of drug addiction. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;45:E11.

Kuhn J, Lenartz D, Huff W, Lee S, Koulousakis A, Klosterkoetter J, et al. Remission of alcohol dependency following deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens: valuable therapeutic implications?. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1152–3.

Hassan O, Phan S, Wiecks N, Joaquin C, Bondarenko V. Outcomes of deep brain stimulation surgery for substance use disorder: a systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2021;44:1967–76.

Zammit Dimech D, Zammit Dimech A-A, Hughes M, Zrinzo L. A systematic review of deep brain stimulation for substance use disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14:361.

Bach P, Luderer M, Müller UJ, Jakobs M, Baldermann JC, Voges J, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens in treatment-resistant alcohol use disorder: a double-blind randomized controlled multi-center trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:49.

Zhou H, Xu J, Jiang J. Deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens on heroin-seeking behaviors: a case report. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:e41–2.

Valencia-Alfonso C-E, Luigjes J, Smolders R, Cohen MX, Levar N, Mazaheri A, et al. Effective deep brain stimulation in heroin addiction: a case report with complementary intracranial electroencephalogram. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:e35–7.

Li N, Wang J, Wang X, Chang C, Ge S, Gao L, et al. Nucleus accumbens surgery for addiction. World Neurosurg. 2013;80:S28.e9–19.

Kuhn J, Möller M, Treppmann JF, Bartsch C, Lenartz D, Gruendler TOJ, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens and its usefulness in severe opioid addiction. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:145–6.

Ge S, Geng X, Wang X, Li N, Chen L, Zhang X, et al. Oscillatory local field potentials of the nucleus accumbens and the anterior limb of the internal capsule in heroin addicts. Clin Neurophysiol. 2018;129:1242–53.

Zhang C, Huang Y, Zheng F, Zeljic K, Pan J, Sun B. Death from opioid overdose after deep brain stimulation: a case report. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83:e9–e10.

Chen L, Li N, Ge S, Lozano AM, Lee DJ, Yang C, et al. Long-term results after deep brain stimulation of nucleus accumbens and the anterior limb of the internal capsule for preventing heroin relapse: An open-label pilot study. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:175–83.

Zhang C, Li J, Li D, Sun B. Deep brain stimulation removal after successful treatment for heroin addiction. Aust N. Z J Psychiatry. 2020;54:543–44.

Rezai AR, Mahoney JJ, Ranjan M, Haut MW, Zheng W, Lander LR, et al. Safety and feasibility clinical trial of nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation for treatment-refractory opioid use disorder. J Neurosurg. 2023;140:231–39.

Hser YI. Predicting long-term stable recovery from heroin addiction: findings from a 33-year follow-up study. J Addict Dis. 2007;26:51–60.

Pettersen H, Landheim A, Skeie I, Biong S, Brodahl M, Benson V, et al. Why do those with long-term substance use disorders stop abusing substances? a qualitative study. Substance Abus. 2018;12:1178221817752678.

Moeller SJ, Hajcak G, Parvaz MA, Dunning JP, Volkow ND, Goldstein RZ. Psychophysiological prediction of choice: relevance to insight and drug addiction. Brain. 2012;135:3481–94.

Parvaz MA, Moeller SJ, Goldstein RZ. Incubation of cue-induced craving in adults addicted to cocaine measured by electroencephalography. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:1127–34.

Bracht T, Soravia L, Moggi F, Stein M, Grieder M, Federspiel A, et al. The role of the orbitofrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens for craving in alcohol use disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:267.

Horn A, Kühn AA. Lead-DBS: a toolbox for deep brain stimulation electrode localizations and visualizations. NeuroImage. 2015;107:127–35.

Horn A, Li N, Dembek TA, Kappel A, Boulay C, Ewert S, et al. Lead-DBS v2: Towards a comprehensive pipeline for deep brain stimulation imaging. NeuroImage. 2019;184:293–316.

Bai L, Ma H, Huang Y, Luo Y. The development of native Chinese affective picture system-a pretest in 46 college students. Chin Ment Health J. 2005;19:719–22.

Parvaz MA, Moeller SJ, Malaker P, Sinha R, Alia-Klein N, Goldstein RZ. Abstinence reverses EEG-indexed attention bias between drug-related and pleasant stimuli in cocaine-addicted individuals. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41:150358.

Maisto SA, Connors GJ. Relapse in the addictive behaviors: integration and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:229–31.

Di Chiara G. Nucleus accumbens shell and core dopamine: differential role in behavior and addiction. Behav Brain Res. 2002;137:75–114.

Salgado S, Kaplitt MG. The nucleus accumbens: a comprehensive review. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93:75–93.

Müller UJ, Voges J, Steiner J, Galazky I, Heinze H-J, Möller M, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens for the treatment of addiction. Ann N. Y Acad Sci. 2013;1282:119–28.

Yuen J, Kouzani AZ, Berk M, Tye SJ, Rusheen AE, Blaha CD, et al. Deep brain stimulation for addictive disorders-where are we now?. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19:1193–215.

Cao Z, Ottino-Gonzalez J, Cupertino RB, Schwab N, Hoke C, Catherine O, et al. Mapping cortical and subcortical asymmetries in substance dependence: Findings from the ENIGMA Addiction Working Group. Addict Biol. 2021;26:e13010.

Grodin EN, Momenan R. Decreased subcortical volumes in alcohol dependent individuals: effect of polysubstance use disorder. Addict Biol. 2017;22:1426–37.

Fenoy AJ, Quevedo J, Soares JC. Deep brain stimulation of the “medial forebrain bundle”: a strategy to modulate the reward system and manage treatment-resistant depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:574–92.

Levy D, Shabat-Simon M, Shalev U, Barnea-Ygael N, Cooper A, Zangen A. Repeated electrical stimulation of reward-related brain regions affects cocaine but not “natural” reinforcement. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14179–89.

Goodman WK, Foote KD, Greenberg BD, Ricciuti N, Bauer B, Ward H, et al. Deep brain stimulation for intractable obsessive compulsive disorder: pilot study using a blinded, staggered-onset design. Biol psychiatry. 2010;67:535–42.

Okun MS, Mann G, Foote KD, Shapira NA, Bowers D, Springer U, et al. Deep brain stimulation in the internal capsule and nucleus accumbens region: responses observed during active and sham programming. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:310–4.

Haq IU, Foote KD, Goodman WG, Wu SS, Sudhyadhom A, Ricciuti N, et al. Smile and laughter induction and intraoperative predictors of response to deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder. NeuroImage. 2011;54:S247–55.

Chaturvedi A, Luján JL, McIntyre CC. Artificial neural network based characterization of the volume of tissue activated during deep brain stimulation. J Neural Eng. 2013;10:056023.

Anderson CJ, Anderson DN, Pulst SM, Butson CR, Dorval AD. Neural selectivity, efficiency, and dose equivalence in deep brain stimulation through pulse width tuning and segmented electrodes. Brain stimul. 2020;13:1040–50.

Ramasubbu R, Clark DL, Golding S, Dobson KS, Mackie A, Haffenden A, et al. Long versus short pulse width subcallosal cingulate stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:29–40.

Morishita T, Fayad SM, Goodman WK, Foote KD, Chen D, Peace DA, et al. Surgical neuroanatomy and programming in deep brain stimulation for obsessive compulsive disorder. Neuromodulation. 2014;17:312–9.

Bewernick BH, Hurlemann R, Matusch A, Kayser S, Grubert C, Hadrysiewicz B, et al. Nucleus accumbens deep brain stimulation decreases ratings of depression and anxiety in treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:110–6.

Henderson MB, Green AI, Bradford PS, Chau DT, Roberts DW, Leiter JC. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens reduces alcohol intake in alcohol-preferring rats. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29:E12.

Franken IH, Kroon LY, Wiers RW, Jansen A. Selective cognitive processing of drug cues in heroin dependence. J Psychopharmacol. 2000;14:395–400.

Franken IH, Stam CJ, Hendriks VM, van den Brink W. Neurophysiological evidence for abnormal cognitive processing of drug cues in heroin dependence. Psychopharmacology. 2003;170:205–12.

Vassoler FM, Schmidt HD, Gerard ME, Famous KR, Ciraulo DA, Kornetsky C, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens shell attenuates cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking in rats. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8735–39.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82171489; No. 81971244; No. 81671366), the Young Stars of Science and Technology Project of Shaanxi Province (No. 2019KJXX-085) and the Science and Technology Innovation Project of Shaanxi Province (No. 2011KTCL03-08) and was sponsored by Suzhou Sceneray Co. Ltd., China, who provided a free DBS apparatus for some patients.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ge SN, Li N, Wang XL and Gao GD designed the clinical trial; Ge SN, Li N, Wang X, Su MM, Zheng ZH, Li JM, Wang X, Wang J and Wang XL performed the surgical procedure and perioperative management for the patients; Chen L recruited the patients and programmed the stimulation parameter of DBS; Qiu C performed the instrument evaluation and followed the clinical outcomes of the patients; Gao GD and Qu Y supervised the implementation of the trial; Li Y and Liu T were responsible for the processing and analysis of the medical images; Li W was responsible for the acquisition and processing of the EEG data; Cai YN conducted the statistical analysis; Ge SN and Li N wrote the manuscript; and Qu Y revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Chen L worked in and received payments from Suzhou Sceneray Co. Ltd. after completing the research work in this trial and graduating from Tangdu Hospital. Owing to the purely academic collaboration, Suzhou Sceneray Co. Ltd. was committed to promoting innovations in DBS treatment for refractory psychiatric disorders and provided only a free DBS apparatus for some patients and instructions for the usage of the apparatus. They were not involved in the study design and implementation, patient care and surgery, or data analysis and interpretation, which were all conducted independently by researchers. All the other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, S., Wang, X., Chen, L. et al. Effects of deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens and anterior limb of the internal capsule on heroin addiction: Over five years of long-term follow-up in a prospective open-label pilot study. Transl Psychiatry 15, 415 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03635-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03635-6