Abstract

Background

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and comorbid intellectual disability (ID) are particularly vulnerable to poor developmental trajectories. These individuals are at increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) relative to those without comorbid ID and the general population. Considering that there could be an important mechanistic link underlying ASD and AD, individuals with these conditions may stand to benefit from similar psychopharmacological treatments.

Methods

This scoping review aimed to evaluate and synthesize the evidence on the effect of AD medications on neurocognitive outcomes in children and adolescents with ASD and low intelligence quotient (IQ). We performed the search according to PRISMA guidelines from inception to May 21st, 2025 in four databases: PubMed, PsycInfo, Scopus, and Web of Science. We included studies of children and adolescents (2 – 21 years) with ASD and low IQ (<85) treated with at least one Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved AD medication (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, benzgalantamine, memantine, aducanumab, lecanemab or donanemab) and investigating neurocognitive outcomes.

Results

Twelve studies met the eligibility criteria. Six studies reported on neurocognitive outcomes from N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist treatment and six studies from cholinesterase inhibitor treatment. Among studies reporting on cholinesterase inhibitors, significant improvement was detected in language (60% of five reporting studies), executive function (100% of two reporting studies), complex attention (100% of one reporting study), and general cognitive ability (50% of two reporting studies). Among the NMDA receptor antagonist studies, evidence of improvement was detected in language (60% of five reporting studies), executive function (75% of four reporting studies), learning and memory (100% of two reporting studies), perceptual-motor functioning (66.6% of three reporting studies), complex attention (100% of one reporting study), and general cognitive ability (50% of two reporting studies). Across studies, treatment with either a cholinesterase inhibitor or an NMDA receptor antagonist was associated with improvements in language, executive function, complex attention, and general cognitive ability. A pattern of significance was detected with age, in that younger children may benefit more from these medications than adolescents.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified promising evidence of neurocognitive improvement in children and adolescents with ASD and low IQ following treatment with either a cholinesterase inhibitor or an NMDA receptor antagonist. Considering the lack of FDA-approved treatments for the cognitive deficits associated with ASD and an absence of medications approved to treat core features of ASD, our findings highlight an opportunity for innovative directions in autism research and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder, defined by persistent impairment in social communication and the presence of restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities [1]. One in 31 children aged eight years and one in 34 children aged four years have been identified with ASD [2]. Furthermore, the expression of ASD is heterogeneous, often presenting with medical and psychiatric comorbidities [3,4,5,6]. A frequently occurring comorbidity with ASD is intellectual disability (ID), which is characterized by deficits in cognitive abilities (Intelligence Quotient [IQ] < 70) and adaptive functioning [1]. Specifically, 39.6% of children aged eight years with ASD also have ID [2]. Among children aged four years with ASD, the prevalence of co-occurring ID is 48.5% (based on the most recent available data from the 2020 ADDM early identification report; estimates for 2022 were not reported) [7]. Individuals with ASD and ID are particularly vulnerable to poor developmental trajectories, showing steady decreases in verbal and nonverbal abilities from 2 to 19 years old [8]. Comparatively, those with ASD in the absence of ID show improvements in verbal and nonverbal abilities over time [8]. Given the dynamic period of brain growth associated with ASD in early life [9], some researchers argue that early cognitive impairment along with the co-occurring period of substantial neuroplasticity may provide a greater risk of negatively altering developmental trajectories [10]. Earlier ASD diagnosis and intervention may counter poor developmental trajectories that lead to worse outcomes [10,11,12,13].

The medical evaluation of children with ASD and co-occurring ID often includes first-tier genetic testing, notably chromosomal microarray to detect copy-number variants and targeted FMR1 CGG repeat analysis to screen for Fragile X syndrome [14]. This practice reflects the growing understanding that ASD with ID is genetically heterogeneous, with many cases linked to rare pathogenic variants [15,16,17]. Recent advances in precision medicine have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of gene-targeted interventions, including Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-based base editing–a technique capable of correcting single-nucleotide variants in vivo [18]. In one recent case, a patient-specific CRISPR base-editing therapy was successfully developed and delivered via lipid nanoparticles to correct a life-threatening urea cycle disorder in infancy [19]. Emerging data also support the use of fetal gene therapy to intervene during prenatal development, a critical period during which irreversible neurodevelopmental damage may begin to accumulate [20]. This evidence suggests that cognitive impairment linked to monogenic causes may not be static and, if targeted early, could be modified before the onset of structural and functional deficits. Although no gene editing therapies have yet been used to directly target cognition-associated genes in humans, gene-targeted interventions are entering clinical use in conditions where cognitive decline is a core feature. For example, a first-in-human intrathecal antisense oligonucleotide (PRAX‑222) targeting gain-of-function SCN2A mutations was administered in pediatric patients with early-onset epileptic encephalopathy under the EMBRAVE trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05737784), demonstrating up to ~44% seizure reduction and absence of treatment-related serious adverse events [21]. Similarly, case studies of GRIN2A and GRIN2B gain-of-function variants have guided NMDA receptor antagonist use (e.g., memantine) in children, showing both seizure control and neurodevelopmental improvement [22, 23]. These therapies demonstrate how gene-informed interventions can be administered before or during early cognitive deterioration. Moreover, recent in vivo animal studies have demonstrated that gene-targeted interventions can reverse or prevent cognitive and neurobehavioral deficits. In a tauopathy mouse model, hippocampal delivery of an adenine base editor (NG-ABE8e) via AAV corrected a pathogenic MAPT variant, reducing tau pathology and rescuing spatial and object memory performance [24]. Similarly, targeted CRISPR activation of the remaining wild-type SCN2A allele in haploinsufficient mice restores vestibulo-ocular reflex plasticity, a neurobehavioral correlate of learning, highlighting the therapeutic relevance of in vivo modulation of cognition-associated genes [25]. Collectively, these findings underscore that cognitive impairment–particularly when rooted in known neurobiological or genetic mechanisms–may be amenable to early therapeutic intervention. While gene-targeted therapies offer long-term potential, pharmacologic strategies that modulate implicated pathways represent a promising and more immediately accessible avenue to enhance neurocognitive outcomes in children and adolescents with ASD and co-occurring ID.

Some individuals with ASD have average or above average intelligence and go on to attend college, maintain employment, and start families [26]. Other individuals have significant deficits in intellectual and adaptive functioning, often requiring continuous lifelong care [26]. Recently, there has been support in the field for the need to recognize differences in IQ to better understand individuals with ASD as well as the differences between individuals [26]. It is now well established that early deficits in cognitive abilities precede ASD manifestation. Low IQ in early infancy and toddlerhood is predictive of ASD diagnosis and may indicate a different etiology relative to children with ASD with IQ scores within or above the average range [27]. Given the potential influence of early individual differences in cognitive abilities on developmental trajectories and the role of IQ in early ASD diagnosis, the question of whether early cognitive enhancement may improve future outcomes remains unexplored.

Recent research investigated developmental trajectories among individuals with ASD and ID. An epidemiological study that examined the prevalence and incidence of dementia among individuals with ASD found that those with ASD and co-occurring ID had a nearly three times increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias in adulthood relative to the general population [28]. Individuals with ASD and co-occurring ID had the highest risk of dementia even when compared to those without co-occurring ID, in addition to being more likely to be diagnosed with early-onset dementia [28]. Given that there could be an important mechanistic link underlying ASD and AD, individuals with these conditions may benefit from similar pharmacotherapeutic treatments.

AD is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by memory impairment and cognitive decline [29]. The first signs often manifest as memory problems (i.e., memory decline that disrupts daily functioning) followed by a decline in other neurocognitive domains [30]. However, biological markers of AD can precede cognitive symptoms by years [30]. Neuropathological changes associated with AD include the aggregation of β-amyloid into plaques, neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau, and brain atrophy [31]. These changes result in neurocognitive impairments associated with AD including deficits in learning, memory, language, and visuospatial skills [32]. Accordingly, it is critical to detect signs of neurocognitive deficits as early as possible to initiate treatment and prevent or delay progression.

There are eight FDA-approved medications to treat cognitive impairment in AD: donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, benzgalantamine, memantine, aducanumab, lecanemab and donanemab. Aducanumab, lecanemab, and donanemab were the most recent drugs that were FDA-approved for the treatment of AD and are monoclonal antibodies that work to substantially reduce β-amyloid aggregates [33,34,35].

Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and benzgalantamine are cholinesterase inhibitors that work by inhibiting the breakdown of acetylcholine released into the synapse, by blocking acetylcholinesterase, thus enhancing cholinergic transmission [36]. In addition to its involvement in AD pathology, the cholinergic system has also been implicated as a potential therapeutic target in ASD [37,38,39,40]. Structural differences in the basal forebrain cholinergic neurons have been identified in postmortem samples from individuals with ASD, including both children and adults [37]. Postmortem studies of adults with ASD have revealed cholinergic dysfunction, including loss of nicotinic receptor in the cerebral cortex and thalamus and reduced muscarinic M1 receptor binding in the cortex [38,39,40].

Memantine is a low affinity antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor [41]. Excessive glutamate-induced excitation plays a role in AD pathology, and memantine is thought to function in preventing excitotoxicity through modulating glutamate activity [41]. The imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission during early development has been proposed as one mechanism involved in the pathology of ASD [42, 43]. Previous clinical studies have reported elevated plasma glutamate levels in individuals with ASD compared to neurotypical controls [44,45,46]. Moreover, neuroimaging studies have reported increased brain glutamate levels in individuals with ASD compared to neurotypical controls, with one study reporting a significant negative association between glutamate levels and IQ [45, 47].

Currently, pharmacological treatments for ASD are limited to addressing irritability, not core symptoms or associated comorbidities [13]. Risperidone (for ages 5 to 16 years) and aripiprazole (for ages 6 to 17 years) are the only FDA-approved medications indicated for the treatment of irritability in ASD [13]. Individuals with ASD are frequently treated with off-label medications (e.g., selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors, stimulants, alpha-2-adrenergic agonists, melatonin, and metformin), but robust evidence regarding their safety and efficacy in pediatric ASD populations remains limited [13, 48]. No pharmacological agents are approved for the cognitive deficits that characterize ASD.

Given the potential neurobiological link between ASD and AD, along with the need for FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of cognitive impairment associated with ASD, it remains to be investigated whether neurocognitive outcomes among individuals with ASD can be improved following treatment with AD medications. A previous systematic review that examined the use of AD medications in ASD was done about 15 years ago and included a sample of individuals across a range of cognitive abilities, however since then, there may have been some new developments [49]. The effect of AD medications on neurocognitive outcomes specific to children and adolescents with ASD and intellectual disability remains to be explored.

Accordingly, the objective herein was to evaluate and synthesize the existing evidence on whether treatment with FDA-approved medications for the cognitive deficits associated with AD impacts neurocognitive outcomes among children and adolescents with ASD and low IQ. Our research questions were: (1) How do AD medications affect neurocognitive outcomes in children and adolescents with ASD and low IQ? (2) Is there evidence for improvement in neurocognitive outcomes from AD medications in children and adolescents with ASD and low IQ? Neurocognitive outcomes were assessed across six neurocognitive domains as recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5): complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor function, and social cognition [1, 50]. Further details are provided in the methods section.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for scoping reviews [51] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [52]. This scoping review was conducted in accordance with an a priori protocol, which was registered on Open Science Framework (https://OSF.IO/8PKRC) [53]. Due to the nature of this scoping review and the guidelines outlined by JBI, critical appraisal of the study methodology was not performed.

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate published empirical studies in humans. An initial limited search of PubMed/MEDLINE was undertaken to identify articles on the topic. The text words contained in the titles and abstracts of relevant articles, and the index terms used to describe the articles were used to develop a full search strategy. The full search strategy was built according to the PCC framework (Population/Concept/Context) in consultation with a librarian and is explained in detail below. The databases that were searched included: PubMed, PsycInfo, Scopus, and Web of Science.

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, we explicitly report both the databases searched and the specific platforms through which each was accessed. PubMed—considered both a database and a search platform and inclusive of MEDLINE records—was searched directly. PsycInfo was searched via the EBSCO platform, Scopus via the Elsevier platform, and Web of Science via the Clarivate platform. In addition to database searching, we conducted backward citation searching (i.e., reference list screening) for all included studies to identify additional relevant records. If any newly identified articles had met inclusion criteria through this process, we planned to perform iterative citation chasing on those as well. This supplementary method ensured that potentially relevant literature not captured by the primary database searches was also considered.

The full search strategies are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Articles published from database inception to May 21st, 2025 were included. Studies published in any language were considered for inclusion. Non-English studies were translated using publicly available tools (e.g., https://translate.google.com/), where necessary, to assess eligibility and extract data.

The search was restricted to published empirical studies involving human participants, using a double NOT strategy—also referred to as a human search hedge. To ensure reproducibility and sensitivity, we applied customized human hedges across databases. For PubMed, the following human hedge was used: NOT ((“Animals”[MeSH] OR “Animal Experimentation”[MeSH] OR “Models, Animal”[MeSH] OR “Vertebrates”[MeSH]) NOT (“Humans”[MeSH] OR “Human experimentation”[MeSH])). Comparable human search hedges were developed for PsycInfo, Scopus, and Embase (see Supplementary Table 1).

Eligibility criteria

Population

This scoping review focused on individuals aged 2–21 years with a diagnosis of ASD. The minimum age was set based on the generally agreed upon reliability of ASD diagnoses starting around 2–3 years of age [54]. The maximum age was set based on the end of adolescence [55]. Because there was no limitation on publication date, studies were expected to have diagnoses from the DSM-4 as well as the DSM-5 [1, 56]. Therefore, ASD diagnoses were based on DSM-5 or DSM-4 criteria (Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Syndrome, or Pervasive Development Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified). All or a subset of participants had low IQ. While individuals with ID have IQ scores approximately two standard deviations or more below the mean (IQ < 70), studies were included with IQ scores that reflected one standard deviation or more below the mean (IQ < 85). Since the focus of this scoping review was not limited to individuals with ID, but to those with below average IQ, only including studies with IQ scores that fell two standard deviations or more below the mean would have been too restrictive. Thus, for the purposes of this scoping review, low IQ was defined as an IQ score that fell one standard deviation or more below the mean.

Concept

This scoping review included studies with the administration of at least one of the following FDA-approved pharmacological interventions for the treatment of neurocognitive symptoms of AD: donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, benzgalantamine, memantine, aducanumab, lecanemab or donanemab. These included studies must have at least one estimate of intellectual ability and assessment of neurocognitive ability. To ascertain if there was evidence of neurocognitive improvement in studies lacking comparison groups, data at baseline and after treatment were compared.

This scoping review included studies that assessed neurocognitive outcomes from at least one neurocognitive domain. The DSM-5 recognizes six neurocognitive domains, each with subdomains: (a) complex attention (i.e., sustained attention, divided attention, selective attention, and processing speed), (b) executive function (i.e., planning, reasoning, working memory, inhibition, and cognitive flexibility), (c) learning and memory (i.e., immediate memory, recent memory, semantic memory, and implicit learning), (d) language (i.e., expressive and receptive), (e) perceptual-motor function (visuospatial and motor), and (f) social cognition (recognition of emotions and theory of mind) [1, 50, 57].

Context

This scoping review included studies conducted in any geographic location and setting, with no limitation on publication date. The search was limited to published empirical papers reporting original work including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, case series, case reports, case control studies, and cross-sectional studies.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they focused on non-ASD populations, individuals without a diagnosis of ASD, individuals with an IQ score greater than 85, and those less than or greater than two and 21 years old, respectively. Studies that did not have at least one estimate of intellectual ability at baseline were excluded. Studies that did not include the administration of at least one AD medication and one assessment of neurocognitive ability were not considered. Reviews, opinion papers, letters to editors, commentaries, and unpublished studies were excluded.

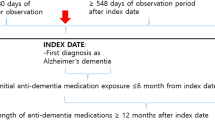

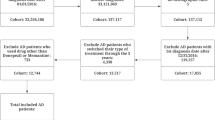

Source of evidence selection

Following the search, all identified records were collated and uploaded into Zotero and duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full and imported into Covidence [58]. The full text of selected citations was assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria. Full-text articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and reasons for their exclusion are provided in Fig. 1. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from included studies by two independent reviewers using a data extraction tool developed in accordance with JBI methodology for scoping reviews [51]. The data extracted included specific details about the author(s), year of publication, country of origin, study population, sample size, study design, intervention and dosage, control, IQ, and neurocognitive outcomes. To assess improvements in neurocognitive outcomes following intervention, outcomes were extracted at baseline and at least one additional timepoint thereafter. In studies that also assessed estimates of IQ (general cognitive ability) following intervention, improvement in IQ was examined. If needed, corresponding authors of included papers were contacted to request missing or additional information.

Results

Study inclusion

The search strategy yielded 404 records after duplicates were removed. Of the 404 records, 16 were identified for full-text review. Twelve studies including a total of 353 participants (range N = 1 – 151) met inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process. The included studies were published between 2002 and 2024. Most of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 9), followed by Canada (n = 1) and Israel (n = 2). Four studies were RCTs [59,60,61,62], one was a prospective open-label trial [63], one was a retrospective open-label trial [64], two were retrospective observational studies [65, 66], three were retrospective case series [67,68,69] and one was a case report [70]. Two RCTs were followed by an open-label extension study [59, 61].

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 12 included studies, six studies (152 participants) reported neurocognitive outcomes following treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor and six studies (201 participants) with an NMDA receptor antagonist in children and adolescents with ASD. Among the cholinesterase inhibitor studies, donepezil treatment was initiated at a dose of 2.5 or 5 mg/day and titrated to maintenance doses ranging from 5 to 10 mg/day; the one rivastigmine tartrate study initiated and maintained treatment at a dose of 0.4 mg twice daily. Treatment duration ranged from 8 to 52 weeks. For the NMDA receptor antagonist studies, memantine treatment was initiated at doses ranging from 2.5 to 10 mg/day and titrated to maintenance doses ranging from 2.5 to 30 mg/day. Treatment duration was variable and ranged from 1.5 to 212 weeks. The full details of the 12 included studies are outlined in Table 1. Tables 2 and 3 provide summaries of the neurocognitive outcomes from RCTs and non-randomized studies, respectively. Table 4 summarizes the neurocognitive outcomes from Handen et al.’s [61] open-label extension studies.

Neurocognitive outcomes following cholinesterase inhibitor treatment in ASD

Six studies [59,60,61, 64, 67, 69] reported neurocognitive outcomes following cholinesterase inhibitor treatment. Of the five studies that reported on language [59,60,61, 67, 69], three (60%) found significant improvements. Gabis et al.’s [60] RCT of 60 children and adolescents reported significant improvements from baseline on the Preschool Language Scale–Fourth Edition [71] after a 24-week washout period (36 weeks from baseline), but not after 12 weeks of treatment with donepezil. Separate analyses of children (age range 5 – 10 years) and adolescents (age range 10 – 16 years) revealed significant improvements in receptive language ability in children, but not adolescents, after 12 weeks of treatment; these improvements persisted after the 24-week washout. Chez et al.’s [59] RCT of 43 children reported significant improvements from baseline on both the Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (ROWPVT) [72] and Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (EOWPVT) [73] after 6- and 12-weeks of treatment with donepezil. Moreover, Chez et al.’s [67] retrospective case series of 32 children detected significant improvements on the EOWPVT following 12 weeks of treatment with rivastigmine tartrate. Nissenkorn et al.’s [69] retrospective case series of 4 children reported significant increases on the expressive language subtest of the Child Development Inventory (CDI) [74] following 12-months of treatment with donepezil, with one patient showing a 94% increase in the subtest score.

Of the two studies that reported on executive function [61, 64], both (100%) detected significant improvements. Hardan & Handen’s [64] retrospective open-label trial of eight children and adolescents reported significant improvement in ratings of hyperactivity on the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) [75] after eight weeks of treatment. Although no treatment effect was detected following the RCT, Handen et al.’s [61] open-label extension study of 14 children and adolescents revealed significant improvements on the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) Sorting Test [76] after 10 weeks of treatment compared to baseline (Table 4) [61].

The one study that reported on complex attention [67] detected significant improvements on the Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS) [77] after 6- and 12-weeks of treatment.

Of the two studies that reported on general cognitive ability (61, 70), one (50%) found significant improvements. Specifically, Nissenkorn et. al.’s study reported significant increases in performance on the CDI [74] following 12 months of treatment.

Neurocognitive outcomes following NMDA receptor antagonist treatment in ASD

Six studies [62, 63, 65, 66, 68, 70] reported neurocognitive outcomes in children and adolescents with ASD following NMDA receptor antagonist treatment. Significant evidence of improvement in learning and memory following memantine administration was found in the two (100%) reporting studies [62, 63]. In Soorya et al.’s [62] RCT of 23 children, significant improvements on the NEPSY-II Narrative Memory-Recognition subtest [78] were reported following 24 weeks, but not after 12 weeks of treatment. Additionally, Owley et al.’s [63] prospective open-label trial of 14 children reported significant improvements on the Children’s Memory Scale–The Dot Locations Subtest [79] after eight weeks of treatment.

Of the five studies [62, 63, 65, 68, 70] that reported on language, three (60%) detected improvements following treatment. Chez et al.’s [68] retrospective case series of 151 children detected significant improvements in language ability following 4 – 8 weeks of treatment. Despite the lack of formal statistical analysis, Bouhadoun et al.’s [65] retrospective observational study of eight children and adolescents found improvements in receptive and expressive language abilities in two patients (treatment duration 2.5 – 53 months) on the basis of clinical evaluations and caregiver reports. Similarly, based on clinical evaluations and caregiver reports, Cosme-Cruz et al. [70] described a 13-year-old male who demonstrated improvements in expressive language after 48 weeks of treatment.

Of the four studies [62, 63, 65, 66] that reported on executive function, three (75%) found improvements following treatment. Bouhadoun et al. [65] reported improvements in working memory in one individual at a 12-month follow-up neuropsychological evaluation after treatment discontinuation. Erikson et al.’s (2007) retrospective cohort study of 18 children and adolescents reported significant improvement in ratings of hyperactivity on the ABC [75]. Significant improvement on the hyperactivity subscale of the ABC was also detected by Owley et al.’s [63] study.

Of the three studies [62, 65, 70] that reported on perceptual-motor functioning, two (66.6%) showed improvements in visuospatial abilities. In Bouhadoun et al.’s [65] study, improvements in visuospatial abilities were reported in one individual at a 12-month follow-up neuropsychological evaluation after treatment discontinuation. Moreover, Cosme-Cruz et al.’s [70] case report detected improvements in visuospatial skills.

The one study [65] that reported on complex attention found improvements. Bouhadoun et al. [65] reported improvements in ratings of attentiveness in one individual following 14 months of memantine treatment.

Of the two studies [62, 63] that reported on general cognitive ability, one (50%) indicated improvements in verbal abilities in memantine-treated individuals. In Soorya et al.’s [62] study, 5 of 7 participants receiving memantine showed ≥10-point improvements in verbal IQ (VIQ), compared with none in the placebo group, indicating a marked treatment-related effect on verbal intelligence.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to evaluate and synthesize the existing evidence on the effect of FDA-approved AD medications on neurocognitive outcomes in children and adolescents with ASD and low IQ. Twelve studies met eligibility for inclusion, and all showed significant evidence for improvement in at least one neurocognitive domain or general cognitive ability following treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor or NMDA receptor antagonist. Of the FDA-approved medications for the treatment of cognitive deficits associated with AD, only three met eligibility criteria for inclusion in this scoping review (i.e., donepezil, rivastigmine tartrate, and memantine). Following treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors, children and adolescents with ASD and low IQ showed neurocognitive improvements in language (60% of five reporting studies), executive function (100% of two reporting studies), complex attention (100% of one reporting study), and general cognitive ability (50% of two reporting studies). Furthermore, NMDA receptor antagonist-treated individuals showed substantial improvements in learning and memory (100% of two reporting studies), language (60% of five reporting studies), executive function (75% of four reporting studies), perceptual-motor function (66.6% of three reporting studies), complex attention (100% of one reporting study), and general cognitive ability (50% of two reporting studies).

The findings from this scoping review revealed improvements in general cognitive ability with memantine treatment among children with ASD and low IQ. It is important to recognize that neurocognitive domains are highly interdependent [57]. General cognitive ability, in particular, supports early information acquisition, which in turn relies on sensory-motor integration, a foundational process in which other cognitive skills emerge [27, 80]. For example, infant memory performance has been linked to later language outcomes and predicts are associated language development beyond 36 months of age [81, 82]. In children with ASD and low IQ, early deficits in general cognition may therefore exert cascading effects on the subsequent development of more specific cognitive domains.

Early learning and verbal ability appear to be impacted by memantine treatment, with two studies [62, 63] reporting significant improvements in learning and memory and one study reporting improvements of 10 points or greater in VIQ [62]. The developmental course of the human central nervous system includes critical periods of increased neuroplasticity in which myriad cellular processes are coordinated, and cognitive abilities develop [9]. Pharmacological interventions targeting these critical periods may be important for redirecting development along optimal trajectories [82]. Research examining prognostic factors of outcomes in ASD consistently indicates that individuals with higher IQs and verbal abilities by age 5 are more likely to have better outcomes in adulthood and that low IQ is predictive of poorer outcomes [83,84,85,86]. Given evidence that early intervention improves outcomes in ASD and preliminary findings suggesting memantine's potential positive effects on verbal and general cognitive abilities, future studies should prioritize younger children with lower cognitive ability who may derive the greatest benefit from treatments targeting early language and learning processes [8, 11].

Overall, a consistent pattern of improvement in executive functioning was observed following treatment with either drug class, as reported in two cholinesterase inhibitor studies [61, 64] and three NMDA receptor antagonist studies [63, 65, 66]. Executive dysfunction in ASD has been implicated across multiple subdomains including planning, cognitive flexibility, and inhibition [87]. Significant improvements in executive function were detected using both standardized and non-standardized measures, suggesting broad effects of treatment across assessment modalities. Age-related patterns also emerged across studies, with younger participants demonstrating earlier or greater neurocognitive gains, consistent with developmental models of executive function maturation [87, 88]. Considering the differences in patterns of executive dysfunction in ASD across developmental periods, future investigations may benefit in conducting separate analyses in children and adolescents when assessing treatment effects.

Noteworthy improvements in the language domain were also detected following treatment with either drug class, as evidenced by three cholinesterase inhibitor [59, 60, 70] and three NMDA receptor antagonist [65, 68, 69] studies. Research examining early language patterns in ASD indicates substantial language delays in toddlers with ASD relative to those with developmental delay in the absence of ASD [89]. Considering that early language ability in ASD is a strong predictor of broader outcomes later in development, the potential for language improvement in children may have profound implications on developmental trajectories [84]. As those with ASD and ID show steady decreases in broad abilities from as early as 2 years of age, the potential benefit from early interventions targeting language improvement is promising [8].

Gabis et al. [60] failed to detect any significant neurocognitive improvements in donepezil-treated children and adolescents after 12 weeks, however, a pattern of significance emerged with age. When assessing for neurocognitive improvement in children (aged < 10 years) and adolescents (aged > 10 years) separately, Gabis et al. [60] found that children showed significant improvements in receptive language 12 weeks earlier than adolescents, suggesting a differential effect of donepezil across developmental periods. Moreover, this improvement was sustained for an additional 6 months following treatment discontinuation. In comparison, Handen et al. [61] did not find significant differences in language outcomes between the treatment and placebo groups after 10 weeks. Given that the sample was older (Mean age = 11.5 years), the absence of significant findings is consistent with patterns detected in Gabis et al. [60].

Notably, there were also important differences across studies with respect to treatment and study durations. Neurocognitive improvements could emerge at different timepoints following treatment and may depend on several factors. Compared to Gabis et al.’s [60] study in which treatment duration lasted 12 weeks, Handen et al. [61] only acquired endpoint measurements following 10 weeks of treatment. Gabis et al. [60] also acquired neurocognitive measurements at 6 months following treatment discontinuation. Additionally, out of the five included NMDA receptor antagonist studies, two studies that reported significant improvements in expressive and receptive language following memantine treatment had the longest treatment durations across participants (10 – 230 weeks) [65, 70]. Future research should address the potential influence of treatment and study durations on neurocognitive improvement.

The precise mechanisms through which NMDA receptor antagonists and cholinesterase inhibitors exert cognitive effects in children remain poorly understood. As noted in the introduction, memantine functions as an NMDA receptor antagonist, whereas donepezil and rivastigmine tartrate are classified as cholinesterase inhibitors [36, 41]. In addition to NMDA receptor antagonism, memantine also exhibits antagonist activity at the serotonergic type 3 (5-HT3) and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors [90,91,92]. Furthermore, there is evidence suggesting memantine is also a dopamine D2 receptor agonist [92, 93]. In addition to its role as a cholinesterase inhibitor, donepezil upregulates nicotinic receptors in cortical neurons and downregulates NMDA receptors [94, 95]. Notably, safety and efficacy data on many medications for the pediatric population are limited and there is much that is still unknown about how these drugs work in this population [96]. The influence of developmental changes on drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, interactions between receptors, and the consequences of these interactions must be studied. It is well established that several factors can alter the effect of a medication including developmental differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [97, 98]. Developmental differences in metabolism, for example, are related to growth and maturational changes throughout development [98]. As influenced by the ratio of liver weight to body weight, liver blood flow is increased in young children compared to adults and can affect metabolic clearance [98]. To date, few studies have evaluated the safety and efficacy of memantine or donepezil in the pediatric population [61, 99, 100]. Well-designed controlled studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of these medications and particularly those looking at younger children with lower IQ are needed to provide clinical recommendations.

A strength of this scoping review is that it has an original focus on the effect of AD medications on neurocognitive outcomes in children and adolescents with ASD and low IQ. Given the promising evidence synthesized in the present scoping review, there may be a need to shift focus from treating core symptoms of ASD (social communication, restricted or repetitive behaviors or interests) to cognitive abilities. Previous large clinical trials that focused on outcomes of core social and communication symptoms failed to show improvement following pharmacological treatment (e.g., oxytocin, citalopram) [101, 102]. Moreover, previous systematic reviews that investigated the effects of one or more AD medications in individuals with ASD focused on outcomes of behavioral or core symptoms of autism and did not focus on neurocognitive outcomes [49, 103]. The original focus of this scoping review and the promising neurocognitive findings across included studies encourage future research towards a new direction of ASD treatment.

This scoping review uncovered important limitations of the literature. Considering the few identified studies for inclusion, additional research is needed to further delineate the effect of AD medications on neurocognitive outcomes in ASD, particularly studies that utilize longitudinal or RCT study designs. Nevertheless, all twelve studies included in this scoping review found evidence of improvement in at least one neurocognitive domain, highlighting an opportunity for new and innovative clinical trials. Particularly, new empirical studies are needed that focus on children with ASD and low IQ. Notably, some studies did not meet eligibility for this scoping review due to the absence of a baseline estimate of cognitive ability. To recognize differences in IQ, future studies should obtain baseline estimates of cognitive ability using well-established standardized instruments (e.g., Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Differential Ability Scales, Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, Mullen Scales of Early Learning, etc.) [104,105,106,107]. Furthermore, information about medical comorbidities for some studies was lacking. Conditions that are known to be related to ASD can alter the presentation of the disorder as well as outcomes from treatment and heterogeneity may obscure potentially therapeutic benefits for more individuals [1, 108, 109]. Moreover, future studies would benefit from the collection of biological specimens to investigate structural and sequence-level genetic variants, which may help clarify individual differences in both the etiology of cognitive impairment and responsiveness to pharmacologic or emerging genetic treatments.

This scoping review identified promising evidence of neurocognitive improvement following treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors or an NMDA receptor antagonist in children and adolescents with ASD and low IQ. Across included studies, NMDA receptor antagonist treatment was associated with improvements in language, executive function, learning and memory, perceptual-motor function, complex attention, and general cognitive ability, with particular gains in VIQ. Cholinesterase inhibitor treatment showed improvements primarily in language, executive function, and complex attention. Treatment effects may vary by developmental stage, with younger children appearing to derive greater benefit. However, the limited number of studies underscores the need for rigorous, well-controlled trials to more precisely evaluate efficacy, mechanisms, and long-term outcomes of these interventions. Future research should employ longer treatment durations, standardized cognitive assessments, and extended follow-up periods. Given the lack of FDA-approved treatments for cognitive impairment or core features of ASD, these findings highlight a critical opportunity to explore the therapeutic potential of these pharmacologic classes for improving neurocognition in this population.

References

American Psychiatric Association D 5 TF. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5TM., 5th ed. [Internet]. 2013. Available from: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=e771ad0f-c0fd-3446-98be-cf79086f265d

Shaw KA, Williams S, Patrick ME, Valencia-Prado M, Durkin MS, Howerton EM, et al. Prevalence and early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 and 8 years – autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 16 Sites, United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill Summaries. 2025;74:1–22.

Charman T, Chandler S, Pickles A, Simonoff E, Loucas T, Baird G. IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders: data from the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Psychol Med. 2011;41:619–27.

Chawner SJ, Doherty JL, Anney RJ, Antshel KM, Bearden CE, Bernier R, et al. A genetics-first approach to dissecting the heterogeneity of autism: phenotypic comparison of autism risk copy number variants. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:77–86. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=222731b6-fb1e-3ebf-85b0-aa822363007d.

Fountain C, Winter AS, Bearman PS. Six developmental trajectories characterize children with autism. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1112–20.

Kim SH, Macari S, Koller J, Chawarska K. Examining the phenotypic heterogeneity of early autism spectrum disorder: subtypes and short-term outcomes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57:93–102.

Shaw KA, McArthur D, Williams AR, Amoakohene E, Hughes MM, Williams S, et al. Early identification of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 4 Years — autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summaries. 2023;72:3–16.

Lord C, Bishop S, Anderson D. Developmental trajectories as autism phenotypes. Am J Med Genet Part C, Semin Med Genet. 2015;169:198–208.

Silbereis JC, Pochareddy S, Zhu Y, Li M, Sestan N. The cellular and molecular landscapes of the developing human central nervous system. Neuron. 2016;89:248–68.

Zwaigenbaum L, Bauman ML, Choueiri R, Kasari C, Carter A, Granpeesheh D, et al. Early intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder under 3 years of age: recommendations for practice and research. Pediatrics. 2015;136:S60–81.

Dawson G. Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:775–803.

Gabbay-Dizdar N, Ilan M, Meiri G, Faroy M, Michaelovski A, Flusser H, et al. Early diagnosis of autism in the community is associated with marked improvement in social symptoms within 1–2years. Autism: Int J Res Pract. 2022;26:1353–63.

Hyman SL, Levy SE, Myers SM. Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. 2020;145:1–64.

Schaefer GB, Mendelsohn NJ. Clinical genetics evaluation in identifying the etiology of autism spectrum disorders: 2013 guideline revisions. Genet Med. 2013;15:399–407.

Myers SM, Challman TD, Bernier R, Bourgeron T, Chung WK, Constantino JN, et al. Insufficient evidence for “Autism-Specific” genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;106:587–95.

Zhou X, Feliciano P, Shu C, Wang T, Astrovskaya I, Hall JB, et al. Integrating de novo and inherited variants in 42,607 autism cases identifies mutations in new moderate-risk genes. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1305–19.

Huang QQ, Wigdor EM, Malawsky DS, Campbell P, Samocha KE, Chundru VK, et al. Examining the role of common variants in rare neurodevelopmental conditions. Nature. 2024;636:404–11.

Komor AC, Kim YB, Packer MS, Zuris JA, Liu DR. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533:420–4 https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=f40475dc-ac5a-3108-be3a-0fcaaa5332bc.

Musunuru K, Grandinette SA, Wang X, Hudson TR, Briseno K, Berry AM, et al. Patient-specific in vivo gene editing to treat a rare genetic disease. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:2235–43.

Jeanne M, Chung WK. Opportunities and challenges of fetal gene therapy. Prenat Diagn. 2025;45:764–71.

Frizzo S A Seamless, Clinical Trial to Investigate the Safety and Efficacy of Multiple Doses of PRAX-222 in Pediatric Participants with Early Onset SCN2A Developmental and Epileptic Encephalopathy [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 13]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05737784

Pierson TM, Yuan H, Marsh ED, Fuentes-Fajardo K, Adams DR, Markello T, et al. GRIN2A mutation and early-onset epileptic encephalopathy: personalized therapy with memantine. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2014;1:190–8. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=f54ae7c9-c662-3102-bcfa-d1684db15a90.

Platzer K, Yuan H, Schütz H, Winschel A, Chen W, Hu C, et al. GRIN2B encephalopathy: novel findings on phenotype, variant clustering, functional consequences and treatment aspects. J Med Genet. 2017;54:460–70.

Gee MS, Kwon E, Song MH, Jeon SH, Kim N, Lee JK, et al. CRISPR base editing-mediated correction of a tau mutation rescues cognitive decline in a mouse model of tauopathy. Transl Neurodegener. 2024;13:1–5.

Tamura S, Nelson AD, Spratt PWE, Hamada EC, Zhou X, Kyoung H, et al. CRISPR activation for SCN2A-related neurodevelopmental disorders. Nature. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09522-w.

Lord C, Charman T, Havdahl A, Carbone P, Anagnostou E, Boyd B, et al. The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. Lancet. 2022;399:271–334.

Denisova K, Lin Z. The importance of low IQ to early diagnosis of autism. Autism Res. 2023;16:122–42.

Vivanti G, Tao S, Lyall K, Robins DL, Shea LL. The prevalence and incidence of early-onset dementia among adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2021;14:2189–99.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:535–62. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=f21f92f4-a85d-3df5-8b2a-aa0c7dccc087.

Weintraub S, Wicklund AH, Salmon DP. The neuropsychological profile of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006171.

Raskin J, Cummings J, Hardy J, Schuh K, Dean RA. Neurobiology of alzheimer’s disease: integrated molecular, physiological, anatomical, biomarker, and cognitive dimensions. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12:712–22.

Corey-Bloom J. The ABC of Alzheimer’s disease: cognitive changes and their management in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(Suppl 1):51–75.

Haddad HW, Malone GW, Comardelle NJ, Degueure AE, Kaye AM, Kaye AD. Aducanumab, a novel anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody, for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: a comprehensive review. Health Psychol Res. 2022;10:31925. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=6dc22770-38a8-34eb-abba-15248b3fc989.

van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, Bateman RJ, Chen C, Gee M, et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:9–21.

Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, Lu M, Ardayfio P, Sparks J, et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330:512–27.

Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2006:CD005593 https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=eb180f79-df50-32b4-95ae-9c7cf642f341.

Kemper TL, Bauman M. Neuropathology of Infantile Autism. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:645.

Lee M, Martin-Ruiz C, Graham A, Court J, Jaros E, Perry R, et al. Nicotinic receptor abnormalities in the cerebellar cortex in autism. Brain. 2002;125:1483–95.

Perry EK, Lee MLW, Martin-Ruiz CM, Court JA, Volsen SG, Merrit J, et al. Cholinergic activity in autism: abnormalities in the cerebral cortex and basal forebrain. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1058.

Ray MA, Graham AJ, Lee M, Perry RH, Court JA, Perry EK. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits in autism: an immunohistochemical investigation in the thalamus. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;19:366–77.

McShane R, Westby MJ, Roberts E, Minakaran N, Schneider L, Farrimond LE, et al. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD003154 https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=7cc300df-eb2d-3e32-a701-1307d15052eb.

Hollestein V, Poelmans G, Forde NJ, Beckmann CF, Ecker C, Mann C, et al. Excitatory/inhibitory imbalance in autism: the role of glutamate and GABA gene-sets in symptoms and cortical brain structure. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:1–9.

Rubenstein JLR, Merzenich MM. Review Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:255–67.

Aldred S, Moore KM, Fitzgerald M, Waring RH. Plasma amino acid levels in children with autism and their families. J Autism Dev Disord. 2003;33:93–7.

Hassan TH, Abdelrahman HM, Abdel Fattah NR, El-Masry NM, Hashim HM, El-Gerby KM, et al. Blood and brain glutamate levels in children with autistic disorder. Res Autism Spectr Discord. 2013;7:541–8.

Shinohe A, Hashimoto K, Nakamura K, Tsujii M, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, et al. Increased serum levels of glutamate in adult patients with autism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:1472–7.

Cochran DM, Sikoglu EM, Hodge SM, Edden RAE, Foley A, Kennedy DN, et al. Relationship among glutamine, γ-Aminobutyric acid, and social cognition in autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2015;25:314–22.

Aishworiya R, Valica T, Hagerman R, Restrepo B. An update on psychopharmacological treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Focus. 2024;22:198–211.

Rossignol D, Frye RE. The use of medications approved for Alzheimer’s disease in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2014;2:87. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=cfd919f3-2938-3194-a498-41d6126b7e5f.

Sachdev PS, Blacker D, Blazer DG, Ganguli M, Jeste DV, Paulsen JS, et al. Classifying neurocognitive disorders: the DSM-5 approach. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:634.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. Int J Evid-Based Healthc. 2021;19:3–10.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Diamandis N. Effect of Alzheimer’s disease medications on neurocognitive outcomes in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and low IQ: a scoping review protocol. 2025. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8PKRC

Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore PS, Shulman C, Thurm A, Pickles A. Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:694–701.

Hardin AP, Hackell JM. Age limit of pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2017;140:1–3.

American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed.. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Harvey PD. Domains of cognition and their assessment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2019;21:227–37.

Covidence Systematic Review Software [Internet]. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; Available from: www.covidence.org

Chez MG, Buchanan TM, Becker M, Kessler J, Aimonovitch MC, Mrazek SR. Donepezil hydrochloride: a double-blind study in autistic children. J Pediatr Neurol. 2003;1:83–8.

Gabis LV, Ben-Hur R, Shefer S, Jokel A, Shalom DB. Improvement of language in children with autism with combined donepezil and choline treatment. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;69:224–34.

Handen BL, Johnson CR, McAuliffe-Bellin S, Murray PJ, Hardan AY. Safety and efficacy of donepezil in children and adolescents with autism: neuropsychological measures. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21:43–50.

Soorya LV, Fogg L, Ocampo E, Printen M, Youngkin S, Halpern D, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes from memantine: a pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2021;31:475–84.

Owley T, Salt J, Guter S, Grieve A, Walton L, Ayuyao N, et al. A prospective, open-label trial of memantine in the treatment of cognitive, behavioral, and memory dysfunction in pervasive developmental disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16:517–24.

Hardan AY, Handen BL. A retrospective open trial of adjunctive donepezil in children and adolescents with autistic disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2002;12:237–41.

Bouhadoun S, Poulin C, Berrahmoune S, Myers KA. A retrospective analysis of memantine use in a pediatric neurology clinic. Brain Dev. 2021;43:997–1003.

Erickson CA, Posey DJ, Stigler KA, Mullett J, Katschke AR, McDougle CJ. A retrospective study of memantine in children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007;191:141–7.

Chez MG, Aimonovitch M, Buchanan T, Mrazek S, Tremb RJ. Treating autistic spectrum disorders in children: Utility of the cholinesterase inhibitor rivastigmine tartrate. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:165–9.

Chez MG, Burton Q, Dowling T, Mina C, Khanna P, Kramer C. Memantine as adjunctive therapy in children diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders: an observation of initial clinical response and maintenance tolerability. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:574–9.

Nissenkorn A, Bar L, Ben-Bassat A, Rothstein L, Abdelrahim H, Sokol R, et al. Donepezil as a new therapeutic potential in KCNQ2- and KCNQ3-related autism. Front Cell Neurosci. 2024;18:1380442 https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=850c4711-a92c-3673-b307-1475555ec103.

Cosme-Cruz RM, de Leon Jauregui M, Hussain M. Cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome: a case report and literature review of available treatments. Psychiatr Ann. 2022;52:41 https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=2eda45ca-bf29-34dd-bfe2-27c798e7a35d.

Zimmerman IL, Steiner VG, Pond RE. Preschool Language Scale, Fourth Edition. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2002.

Gardner MF Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test: ROWPVT. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications; 1985.

Gardner MF Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test (Revised): EOWPVT-R. Novato, CA: Academic Therapy Publications; 1990.

Ireton H, Glascoe FP. Assessing children’s development using parents’ reports: The Child Development Inventory. Clin Pediatr (Philos). 1995;34:248–55.

Aman MG. The aberrant behavior checklist: a behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am J Ment Defic. 1985;89:485–91.

Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001.

Conners CK. Conners’ Parent Rating Scale. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc; 1989.

Korkman M, Kirk U, Kemp S. NEPSY-II: Clinical and interpretive manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2007.

Cohen MJ. Children’s Memory Scale: Administration manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1997.

Kuhl PK. Brain mechanisms in early language acquisition. Neuron. 2010;67:713–27.

Rose SA, Feldman JF, Jankowski JJ. A cognitive approach to the development of early language. Child Dev. 2009;80:134–50.

Nelson CA III, Gabard-Durnam LJ. Early adversity and critical periods: neurodevelopmental consequences of violating the expectable environment. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43:133–43.

Chenausky K, Norton A, Tager-Flusberg H, Schlaug G. Behavioral predictors of improved speech output in minimally verbal children with autism. Autism Res. 2018;11:1356–65.

Howlin P, Klin A, Cohen D, Volkmar FR, Paul R. Outcomes in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2005. pp. 201–20.

Venter A, Lord C, Schopler E. A follow-up study of high-functioning autistic children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1992;33:489–597.

Matson J, Horovitz M. Stability of autism spectrum disorders symptoms over time. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2010;22:331–42.

Hill EL. Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:26–32.

Bergh S, Scheeren A, Begeer S, Koot H, Geurts H. Age related differences of executive functioning problems in everyday life of children and adolescents in the autism spectrum. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44:1959–71.

Weismer SE, Lord C, Esler A. Early language patterns of toddlers on the autism spectrum compared to toddlers with developmental delay. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40:1259–73.

Aracava Y, Pereira EFR, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX. Memantine Blocks α7* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors more potently than N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptors in rat hippocampal neurons. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2005;312:1195–205.

Rammes G, Rupprecht R, Ferrari U, Zieglgänsberger W, Parsons CG. The N-methyl- d-aspartate receptor channel blockers memantine, MRZ 2/579 and other amino-alkyl-cyclohexanes antagonise 5-HT 3 receptor currents in cultured HEK-293 and N1E-115 cell systems in a non-competitive manner. Neurosci Lett. 2001;306:81–4.

Seeman P, Caruso C, Lasaga M. Memantine agonist action at dopamine D2High receptors. Synapse. 2008;62:149–53.

Spanagel R, Eilbacher B, Wilke R. Memantine-induced dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex and striatum of the rat — a pharmacokinetic microdialysis study. Eur J Pharm. 1994;262:21–6.

Reid RT, Sabbagh MN. Effects of donepezil treatment on rat nicotinic acetylcholine receptor levels in vivo and in vitro. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2003;5:429–36.

Shen H, Kihara T, Hongo H, Wu X, Kem W, Shimohama S, et al. Neuroprotection by donepezil against glutamate excitotoxicity involves stimulation of alpha7 nicotinic receptors and internalization of NMDA receptors. Br J Pharm. 2010;161:127–39.

Committee On Drugs, Neville KA, Frattarelli DAC, Galinkin JL, Green TP, Johnson TD, et al. Off-Label Use of Drugs in Children. Pediatrics. 2014;133:563–7.

Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SW, Blowey DL, Leeder JS, Kauffman RE. Developmental pharmacology — drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1157–67.

van den Anker J, Reed MD, Allegaert K, Kearns GL. Developmental Changes in Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. J Clin Pharm. 2018;58:25.

Aman MG, Findling RL, Hardan AY, Hendren RL, Melmed RD, Kehinde-Nelson O, et al. Safety and efficacy of memantine in children with autism: randomized, placebo-controlled study and open-label extension. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27:403–12.

Hardan AY, Hendren RL, Aman MG, Robb A, Melmed RD, Andersen KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of memantine in children with autism spectrum disorder: Results from three phase 2 multicenter studies. Autism. 2019;23:2096–111.

King BH, Hollander E, Sikich L, McCracken JT, Scahill L, Bregman JD, et al. Lack of efficacy of citalopram in children with autism spectrum disorders and high levels of repetitive behavior: citalopram ineffective in children with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:583–90.

Sikich L, Kolevzon A, King BH, McDougle CJ, Sanders KB, Kim SJ, et al. Intranasal oxytocin in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1462–73.

Brignell A, Marraffa C, Williams K, May T. Memantine for autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;8:CD013845 https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=d177f1c5-3287-3884-a8c2-68ca01d99f1b.

Wechsler D Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fourth Edition (WISC-IV): Administration and scoring manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003.

Elliot CD Differential Ability Scales. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment;2007.

Roid GH Standford-Binet Intelligence Scales. Fifth Edition. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2003.

Mullen EM Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service Inc.

Grove J, Ripke S, Als TD, Mattheisen M, Walters RK, Won H, et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:431–44. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=c6501d39-e631-3606-8957-c1d5358eab83.

Rolland T, Cliquet F, Anney RJL, Moreau C, Traut N, Mathieu A, et al. Phenotypic effects of genetic variants associated with autism. Nat Med. 2023;29:1671–80.

Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA California Verbal Learning Test-Second Edition (CVLT-II). The Psychological Corporation; 2000.

Buschke H. Selective reminding for analysis of memory and learning. J Verbal Learn Verbal Behav. 1973;12:543–50.

Swanson JM, Kinsbourne M. Stimulant-related state-dependent learning in hyperactive children. Science. 1976;192:1354–7.

Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition (KBIT-2) Manual. Second Edition. Bloomington, MN: Pearson; 2004.

Williams KT. Expressive Vocabulary Test, Second Edition (EVT-2). San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2007.

Bruininks RH, Bruininks BD. Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2): Manual. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson; 2005.

Dunn W Sensory Profile: User’s Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999.

Hickman LA. The apraxia profile: a descriptive assessment tool for children. San Antonio, TX: Communication Skill Builders; 1997.

Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (WASI-II). San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2011.

Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service Inc; 1959.

Raven J, Raven J. Raven Progressive Matrices. In: Handbook of nonverbal assessment [Internet]. 2003. p. 223–37. Available from: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=94df6997-bde9-3423-be71-a0dc12dc5360

Guy W, National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.). Psychopharmacology Research Branch., Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Program. ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rev. Rockville, Md: U. S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs; 1976. (DHEW publication; no. (ADM) 76-338).

Harrison P, Oakland T. Adaptive Behavior Assessment System–Second Edition Manual (ABAS-II). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment; 2002.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Jill Cirasella, MLIS, MSc, Associate Librarian for Scholarly Communication, City University of New York Graduate Center, for assistance with devising a search strategy for this scoping review. We thank Kenneth A. Myers, MD, PhD, FRCPC, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Neurology, McGill University Health Centre, for clarifying discordant data on the number of participants diagnosed with ASD in Bouhadoun et al. [65]. We also thank Latha V. Soorya, PhD, BCBA, Department of Psychiatry, Rush University Medical Center, for assistance in providing additional IQ data for Soorya et al. [62]. Finally, we thank Michael Chez, MD, FAAN, FAES, Director of Pediatric Neurology, Epilepsy & Autism at Sutter Neuroscience Institute, for providing additional information regarding the cognitive functioning of participants in Chez et al. [59, 67, 68].

Funding

The work was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH121605 (PI: Kristina Denisova), the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) under Award Number 614242 (PI: Kristina Denisova), and faculty start-up funds. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no role in study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of this report, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Denisova had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Diamandis, van den Anker, Denisova. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Diamandis, van den Anker, Denisova. Drafting of the manuscript: Diamandis, van den Anker, Denisova. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Diamandis, van den Anker, Denisova. Statistical analysis: Denisova, Diamandis. Obtained funding: Denisova. Administrative, technical, or material support: Denisova. Study supervision: Denisova.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Diamandis, N., van den Anker, J.N. & Denisova, K. Effect of Alzheimer’s disease medications on neurocognitive outcomes in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and low IQ: a scoping review. Transl Psychiatry 15, 475 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03655-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03655-2