Abstract

Suicidal thoughts and behaviours (STBs) are major public health concerns. Despite much research focus on grey matter abnormalities in STBs, the study of white matter tracts that connect the brain regions implicated in STBs has received relatively less attention. Hence, we conducted the first meta-analysis of whole-brain voxel-based diffusion tensor imaging studies in STBs to elucidate the most robust white matter microstructure abnormalities relative to controls. Fourteen DTI datasets were included, comprising 289 individuals with a history of STBs and 506 controls. Anisotropic effect-size signed differential mapping, a voxel-based meta-analytic method, was used to examine regions of altered fractional anisotropy (FA) in individuals with STBs compared to controls. Individuals with a history of STBs had significantly lower FA in bilateral inferior longitudinal fasciculus, inferior frontal-occipital fasciculus, uncinate fasciculus, fornix, cingulum bundle and corpus callosum body than controls. There were no regions with increased FA. Findings remained in subgroup analyses of adult and drug-free samples. Decreased FA in the right fronto-limbic-occipital cluster was more severe in younger individuals and females with STBs than controls. STBs are associated with microstructural abnormalities particularly evident in the ventral fronto-limbic, visual-limbic-OFC and callosal body pathways, suggesting that the neural pathways involved in emotion and sensory processing are specifically compromised in this population. Insights into the neurobiological abnormalities associated with STBs are important as they encourage greater efforts to examine treatments to normalise these morphological alterations and reduce suicide deaths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicidal thoughts and behaviours (STBs) are major public health concerns. Around 1 million people die by suicide yearly and suicide is the second leading cause of death among youths globally [1]. Currently, the predictive value of identified non-biological risk factors for STBs is still limited [2]. The identification of a neural signature of STBs could be a potential biomarker for suicide risk, particularly when suicidal intentions are denied or unrecognised in initial evaluations. Hence, it is crucial to advance our understanding of the neural mechanisms underpinning STBs and elucidate reliable biological risk markers to develop more effective preventive strategies and targeted treatments to reduce suicide fatalities.

Emerging evidence underscores the role of emotion dysregulation in STBs. Recent MRI review studies reported that across mental disorders, STBs are associated with grey matter volume (GMV) reductions in several brain regions subserving emotion and impulse regulation including the ventral prefrontal cortex (VPFC), dorsal prefrontal cortex (DPFC), anterior cingulate, amygdala, insula and middle/superior temporal cortices [3, 4]. Functionally, STBs are associated with increased lateral VPFC activation during cognitive control, response inhibition and processing of negative emotions, with increased middle/superior temporal activation during emotion processing, with blunted ventral striatal activation during reward processing and with reduced frontolimbic connectivity during resting-state [3, 4]. It has been further proposed that alterations within the extended VPFC system may potentiate suicidal thoughts and together with perturbations in top-down and bottom-up connections contribute to suicidal behaviours [4].

Despite much research focus on GMV abnormalities in STBs, the study of white matter (WM) tracts that connect the brain regions implicated in STBs has received relatively less attention. Increasing evidence suggests a dysconnectivity hypothesis that STBs may be related to inefficient or abnormal WM pathways [5]. Brain regions do not function independently; they are interconnected through a complex system of short-and long-range WM tracts [6]. WM connections convey information between distant brain regions, regulating the speed and timing of activation across neural networks, which are essential for optimal performance of higher-order tasks that rely on integrated information processing [7].

Diffusion imaging measures the diffusion of water molecules and can be used to either indirectly model trajectories of WM tracts or show subtle variability within WM using MR images based on diffusion metrics [8]. Fractional anisotropy (FA) is a commonly used metric calculated using the relative directionality of water diffusion within single voxels [9], which may reflect aspects of membrane integrity and myelin thickness, where decreased FA is usually associated with WM disruption [9]. Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) is a fully automated approach that allows whole-brain analysis of WM in a voxel-wise manner, which allows the identification of differences within specific regions of WM instead of averaging across the entire tract bundle [10].

Several whole-brain and regions-of-interest (ROI) studies have reported that STBs are associated with reduced FA in various large WM tracts, particularly the uncinate fasciculus connecting the anterior temporal lobe with the medial and lateral OFC [11,12,13] corpus callosum connecting the left and right cerebral hemispheres [5, 12, 14]; inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF) connecting the occipital and OFC areas via the external capsule [5, 12, 15]; inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) connecting the occipital with the anterior temporal cortex [16, 17]; and cingulum bundle (CB) connecting subcortical nuclei to the cingulate gyrus [16, 18].

Therefore, the focus of this meta-analysis of whole-brain voxel-based DTI studies in STBs was to reliably identify WM microstructural abnormalities measured by changes in anisotropy most consistently implicated in STBs. Given that STBs are increasingly considered as transdiagnostic symptoms occurring in a variety of psychiatric disorders and they can also occur in the absence of manifest psychopathology; hence, this meta-analysis examined STBs as psychopathological phenomena of a disturbed mental state across various comorbid psychiatric conditions. We hypothesised that STBs would be associated with reduced FA in major fronto-limbic tracts subserving emotion and impulse regulation.

Methods

Study selection

Using PubMed, ScienceDirect, Web of Knowledge, and Scopus, we conducted a comprehensive literature search to identify DTI papers in STBs published up to 30 December 2023 with the following search terms: “suicide,” “suicidal,” and “suicidality” (separated by OR) in combination with the terms “diffusion tensor imaging,” “DTI,” “diffusion weighted imaging,” “TBSS,” and “whole-brain” (separated by OR). In addition, reference lists of included studies were hand-searched for suitable papers. We systematically checked study quality concerning design, demographic/clinical characteristics (e.g., overlap of study samples) and precision of result coordinates. As there is no standard checklist or tool for the quality assessment of MRI studies, we adopted a quality assessment tool for this meta-analysis based on a previous meta-analysis [19] (Table S2). In cases where articles provided insufficient data such as conference presentations, corresponding authors were contacted to obtain the required information. Studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) be published in English in a peer-reviewed journal, (2) use whole-brain analysis, (3) include comparison subjects, (4) use DTI as the imaging methodology reporting differences in FA, and (5) include more than 10 participants. We limited our analysis to the FA results as other diffusivity measures were reported too infrequently to allow useful meta-analysis. Studies were excluded if peak coordinates or parametric maps could not be retrieved from the published article or after contacting the authors, and if they did not use consistent statistical thresholds throughout the brain. The authors (LL and JR) independently evaluated the identified studies for inclusion. We made no restrictions concerning age, psychiatric comorbidities, medication status and drug abuse history to ensure maximal study coverage, but we conducted several sub-group analyses later on. Finally, literature search results were compiled and uploaded to EndNote library (X9), a specialised software for organising bibliographies. MOOSE guidelines for meta-analysis of observational studies were followed [20] (Table S1).

SDM meta-analysis

Regional differences in FA between individuals with STBs and controls were analysed using the Anisotropic Effect Size-Signed Differential Mapping (AES-SDM) software version 5.15 (https://www.sdmproject.com/). As previously described [21, 22], AES-SDM first creates an effect-size map and a variance map for each study based on peak information (coordinates, effect size and direction of change) reported and a template of the TBSS and the spatial covariance of FA [23]. Notably, those peaks that did not appear statistically significant at the whole-brain level, were excluded; that is, while different studies may employ different thresholds, we ensured that the same statistical threshold throughout the brain was used in each study. This was intended to avoid biases towards liberally thresholded brain regions, which is common for small volume corrections and ROIs. Study maps were then meta-analysed using standard random-effects meta-analytic methods which take into account sample size, study precision and between-study heterogeneity. Finally, the meta-analytic effect-size map is statistically assessed by comparison to a null distribution created with a permutation algorithm.

We took a detailed approach to ensure that only the most replicable and robust results were retained. First, a jackknife sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the reproducibility of the results by iteratively repeating the same analysis, excluding one data set at a time to establish whether the results remained significant [24]. Similarly, a heterogeneity analysis was conducted to determine whether there was significant unexplained between-study variability within the results [21]; following usual convention, we defined relevant heterogeneity as either an I2 statistic ≥50%. In case of relevant heterogeneity, we would check whether it decreases in subgroup analyses or meta-regressions. To examine publication bias, asymmetry of funnel plots was tested using Eggerʼs test as implemented in the AES-SDM software.

Finally, we conducted sensitivity subgroup analyses on studies that included only adults, drug-free participants or suicide attempters, as well as meta-regression analyses with age and gender. The standard AES-SDM threshold of p = 0.005 with peak Z > 1 and a cluster extent of >10 voxels was used for all the analyses to provide the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity [21].

Tract identification

The clusters obtained through the SDM analysis were next analysed with the lesion analysis tool in MegaTrack Atlas (https://megatrackatlas.org/) to determine which tracts intersected the clusters. We chose the BRC Atlas dataset and included the full available sample (age range 18–84 years), yielding a probabilistic WM atlas based on 140 brains. We tested the clusters against tractography derived from both the tensor model and spherical deconvolution, and only included tracts that had more than 25% probability of intersecting the clusters (this is the default setting in the MegaTrack lesion analysis tool).

Results

Sample characteristics

The search yielded 20 whole-brain TBSS studies, six of which were excluded: two studies examined correlations with STBs measures without a control group, two studies did not report the peak MNI coordinates and the authors contacted no longer have access to the original data, and two studies were conference proceedings and the authors were uncontactable. The quality of the included studies was deemed good (Table 1).

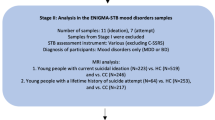

The 14 studies included in the final meta-analysis comprised 289 individuals (82 adolescents/young adults and 207 adults) with STBs and 506 controls (111 adolescents/young adults and 395 adults). There were 10 adult studies (mean age > 21 years) and four adolescent/young adult studies (mean age < 21 years). Studies classified participants as suicide attempters if they had at least one past suicide attempt with intent to die assessed through clinical interviews including the Columbia Suicide History Form [25] and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) [26]. Participants with current suicidal ideation was classified using the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS) suicide items [27] and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) suicidality assessment [28]. All studies excluded participants with medical conditions that could have adversely affected growth and development. Three studies recruited unmedicated participants and 11 studies included drug-free participants. All studies examined participants with comorbid psychiatric conditions, particularly major depressive disorder (MDD) (6 studies), bipolar disorder (BD) (6 studies) and schizophrenia (2 studies). No significant differences in age were found between participants with STBs and controls, reflecting the group matching in the original studies. Table 1 summarises the participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics. All studies had received ethical approval from their respective ethics boards.

Changes in fractional anisotropy

Individuals with STBs, relative to controls, showed significantly reduced FA in three clusters: a left and a right fronto-temporo-occipital cluster consisting of the UF, ILF, IFOF and fornix as well as a cluster comprising the body of the corpus callosum and right cingulum bundle. There were no regions with increased FA (Table 2, Fig. 1).

A AES-SDM identified three white matter clusters of significantly reduced FA in individuals with STBs compared to controls. B The MegaTrack Atlas lesion analysis tool showed that the three clusters intersect with six major white matter tracts. The tracts are visualised here along with the clusters (shown in white). CC: corpus callosum; Cing: cingulum; Fnx: fornix; IFOF: inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus; ILF: inferior longitudinal fasciculus; Unc: uncinate fasciculus.

We did not detect relevant heterogeneity (I2 ≤ 50%) or publication bias (Egger’s test p values > 0.05) in these findings (Figure S1).

Reliability and subgroup analyses

Jackknife sensitivity analyses revealed that reduced FA in the three clusters, namely: the left fronto-temporo-occipital, right fronto-temporo-occipital and corpus callosum clusters were highly replicable as they remained significant in 14 combinations of studies (Table S3).

The main meta-analysis findings remained in subgroup analyses of 10 adult studies (207 STBs and 395 controls), 11 drug-free studies (226 STBs and 413 controls) and 13 suicide-attempter studies (268 STBs and 453 controls) (Figure S2). (i.e., the subgroups analyses showed statistically significantly reduced FA in clusters that were visually similar to the three of the main analysis; Table S4).

Meta-regression analyses: effects of age and gender

Age, as measured by the mean age of participants reported in each included study, was positively correlated with FA of the right fronto-temporo-occipital cluster (x = 42, y = −2, z = −28; Z = 1.33, p = 9×10−7), which has been robustly detected as atypical in the main analysis (Figure S3a). Younger individuals with STBs had smaller FA in the right fronto-temporo-occipital cluster relative to age-matched controls. Female participants with STBs also had significantly smaller FA in the right fronto-temporo-occipital cluster (x = 40, y = −2, z = −24; Z = 1.08, p = 2×10−5) than female controls (Figure S3b).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of whole-brain voxel-based DTI studies in STBs. Individuals with STBs, across psychiatric diagnoses, exhibited significantly reduced FA in left and right fronto-temporo-occipital clusters comprising the UF, ILF, IFOF and fornix as well as in a cluster comprising the corpus callosum body and right cingulum bundle relative to controls. The findings are robust and remained in subgroup analyses of adult, drug-free and suicide attempter samples. Decreased FA in the right fronto-temporo-occipital cluster was also more severe in younger individuals and females with STBs relative to controls.

Increasing evidence implicates abnormalities in the limbic system in STBs. Recent reviews of brain correlates of STBs have consistently underscored the critical role of amygdala that subserves emotional processing and regulation [4, 29]. The UF, which is part of the limbic system, connects the OFC to the anterior temporal lobes and plays a major role in social emotional processing that is instrumental in decision-making and shaping behaviours, where disruption of the UF may affect social reward processing and social learning [30]. Hence, UF perturbation may possibly underlie the dysfunctional emotional processing and regulation commonly observed in suicidal individuals, as well as disrupt the individual’s ability to acquire social reward or punishment-based learning [31], which manifest as poor decision making such as suicide attempt.

The current meta-analytic association between STBs and microstructural abnormalities of the UF is consistent with recent ROI studies that reported lower FA in the UF in adolescents and young adults with future STBs [32], self-injury behaviours [16] and prior suicide attempts [13] relative to controls, and is further underpinned by finding of a negative correlation between UF FA and suicide ideation [13]. Additionally, a post-mortem study reported significantly lower relative telomere length in oligodendrocytes obtained from the UF of brain donors with MDD who died by suicide relative to healthy age-matched control donors, which further support the association between UF abnormalities and suicidal behaviour [33].

The fornix is a major limbic tract connecting the hippocampus to the hypothalamus, two key stress-regulatory structures of the brain [34], and is involved in the regulation of emotion brain regions [35] and in stress response [36]. Reduced FA of the fornix is associated with chronic stress [37], prolonged cortisol reactivity to psychological stress [38] and childhood trauma [39]. The fornix is also pivotal for episodic memory functioning that guide decisions [40]. Notably, emerging findings including meta-analytic evidence underscore an association between memory impairment and STBs [41, 42]. Hence, given that STBs result from a complex interplay between stressful events and cognitive vulnerability factors including memory deficits, perturbations in this structure may attenuate memory function impeding individuals with STBs from using past experiences to solve current problems effectively leading to suicide decisions.

The CB, another key limbic tract, supports not only affective processing but also bottom-up somatosensorial affective processing and emotional expression or experiential emotion regulation, which facilitates the modulation of negative emotional experiences and recovery from emotionally stressful events [43]. Hence, microstructural abnormalities of the CB may possibly contribute to an overall maladaptive emotion functioning that hinders the effective regulation of an emotionally painful episode during a suicide crisis. Earlier ROI and correlational studies have reported negative associations between cingulum FA and suicidality in adults with BD [44], and self-injury severity [45] and duration [16] in adolescents and young adults with MDD. Hu et al. further successfully differentiated between MDD patients with and without self-injury using both the cingulum FA and emotional dysregulation score.

Several lines of research suggest that callosal interaction is necessary for transferring emotional information between the hemispheres to facilitate emotional interpretation and expression underscoring the critical role of the corpus callosum in cognitive processing of emotions [46]. Given that individuals who engaged in self-harming behaviours have atypical pain tolerance and threshold [47], some studies have proposed that a generalised deficit in the somatosensory information processing and modulation may potentially underlie the emotional dysregulation observed in self-harming suicidal individuals [48]. Hence, given that the body of the corpus callosum connects the motor and sensory cortices with projections to medial frontal regions implicated in top-down emotion control [34], callosal body abnormalities, in particular, may contribute to the disturbances in emotional and sensory processing associated with STBs.

The current finding of reduced microstructural integrity of the callosal body extends prior ROI studies that reported lower callosal body FA in suicidal patients with BD or MDD relative to non-suicidal patients and healthy controls [49, 50], as well as in adolescents and young adults with self-injury behaviours across psychiatric diagnoses [16], where FA of the callosal body was furthermore negatively related to the number of suicide attempts [49], thereby suggesting a specific implication of this region in the severity of the suicidal behaviour. The finding also extends earlier MRI studies that consistently reported macrostructural abnormalities in the corpus callosum in individuals with STBs, independently from any psychiatry disorders [51, 52].

The ILF and IFOF are key components of the visual-limbic pathway involved in the visual processing of emotionally significant stimuli [53]. Consistent with the current findings, prior ROI studies reported microstructural abnormalities of the ILF and IFOF in adolescents and young adults with self-injury behaviours [16] and in suicidal patients with panic disorder [54]. Furthermore, functional connectivity studies also reported negative correlation between fronto-visual networks and suicidal ideation in MDD patients [55].

The Emotional paiN and social Disconnect (END) brain model of suicidality posits two key neural circuits implicated in suicidal behaviour; the emotional pain circuit consisting of the amygdala, hippocampus and cerebellum, and the social disconnect circuit consisting of the lateral OFC, temporal gyri and the connections between them [56], which also correspond to the suicide risk-related diathesis traits of excessive subjective distress and social distortion in the brain-centric model of suicidal behaviour [57]. The current meta-analytical findings of structural connectivity abnormalities in STBs showed similar aberrations in the neural circuitries implicated in the models, particularly the OFC-temporal and limbic networks. This is also consistent with a recent review that highlighted alterations in the frontal, temporal and limbic regions in STBs [29].

In addition, we propose incorporating the sensory system in the brain model of STBs. For instance, disruption in sensory processing may affect the individual’s ability to detect and interpret social cues accurately thereby increasing the occurrence of interpersonal stress and experience of social disconnect, which may heighten suicide risk. Deficits in sensory modulation may result in over-reaction to external stimuli and together with deficits in emotional regulation further exacerbate emotional distress and increase suicide tendency. Studies using network-based statistical approaches also reported decreased functional connectivity in suicide attempters relative to heathy controls in subnetworks including the visual [55] motor and somatosensory regions [58, 59]. It has been postulated that abnormalities in functional connectivity reflect abnormal WM microstructure which shapes brain connectivity [60]. Hence, the findings of WM alterations in the callosal body and fronto-limbic-visual pathways may suggest disruption in the networks mediating sensory integration and cognitive or emotion regulation to sensory stimuli, which may possibly underlie the atypical emotion and sensory processing in suicidal individuals [48].

The human brain is a highly plastic organ that is continually modified by experience and undergoes changes across the lifespan [61]. Adverse childhood experiences, particularly childhood maltreatment, are associated with increased risk of attempted suicide throughout the life-span [62] and widespread reduced WM integrity [39, 63]. It is worth noting the similarities between the neural correlates of STBs and childhood maltreatment. For instance, meta-analyses of structural connectivity and GMV studies in childhood maltreatment also reported significantly reduced FA in the callosal body and fronto-limbic-occipital pathways presumably involved in conveying and processing the (aversive) experience [39], as well as reduced GMV in OFC-limbic-temporal regions that mediates top-down affect control and in the sensorimotor cortex that mediates sensory functions [64]. Hence, we cautiously speculate that early interpersonal stressful experiences may possibly contribute to the observed aberrations in neural pathways linking frontal, limbic and sensory regions in STBs. Furthermore, given that the UF, ILF and IFOF have a relatively protracted development with FA increase peaking in early adulthood [65], these fronto-limbic and visual-limbic-OFC pathways may also be susceptible to impairment in individuals exposed to stressful events later in adulthood thereby exacerbating their vulnerability for STBs. However, the adverse impact of stress may be more detrimental during early developmental period as suggested by the current meta-regression finding that showed an age effect on lower FA in the visual-emotional processing tracts in younger suicidal individuals.

The observed sex effect of reduced FA in the visual-emotional processing tracts is noteworthy and highlights the need to identify sex-specific biomarkers associated with suicide. Emerging research underscores the role of ovarian hormone fluctuations in STBs given the strong association between the perimenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle and acute risk for STBs [66, 67]. Specifically, the perimenstrual phase is associated with increases in negative affect, inhibitory control deficits and interpersonal rejection sensitivity, which may contribute to emotional distress and social disconnectedness and in turn heighten risk for STBs, particularly for at-risk girls with early-life adversity [66, 68]. Furthermore, a recent study reported that females exhibited lower FA in several WM tracts including the ILF and IFOF than males when exposed to stress, and they were also more affected when early-life stress is followed by recent stress in adulthood [69]. Hence, it seems that the adverse effect of stress exposure on the WM microstructure integrity may be greater in females, particularly adolescent girls, which may further increase their vulnerability for STBs. Furthermore, given the consistently reported sex differences in MDD, particularly in epidemiology, clinical symptomatology and brain morphology [70,71,72], the current meta-analytical finding of sex differences in the visual-emotional processing tracts may plausibly reflect the underlying sex differences in structural brain alterations in MDD as most of the studies included patients with depression. Nonetheless, future longitudinal studies may explore this sex effect further, as these potential sex-specific neural markers may aid the development of sex-specific targeted interventions thereby improving clinical outcomes.

From a translational/clinical perspective, the identification of brain networks associated with suicide risk combined with sophisticated machine learning approaches could be used to identify at-risk individuals, which would be particularly useful when suicidal intentions are denied or unrecognised in initial traditional clinical assessments. Also, the more detailed delineation of brain networks involved in suicide risk could be used to target specific regions for treatments. For instance, transcranial magnetic stimulation of the DLPFC influences functional activity in the OFC, one of the key regions associated with the neural pathways identified in this meta-analysis and has been found to be dysfunctional in prior functional MRI studies of suicide [4, 73].

Limitations

This meta-analysis has several limitations, some of which are inherent to meta-analyses. First, it was based on peak coordinates and effect sizes from published studies, rather than raw statistical brain maps, and this approach may result in less accurate results [21]. Second, while voxel-wise meta-analytic methods provide excellent control for false positive results, false negative results are more difficult to avoid [21]. Third, the studies included participants with various comorbid psychiatric conditions making it difficult to elucidate the shared vs. independent neural substrates of STBs across different mental disorders. Notably, the STBs literature largely includes studies on mood disorders particularly depression, with converging evidence suggest that uncinate fasciculus and corpus callosal FA reductions may be important in suicide risk across mood disorders [4]. This is consistent with the current meta-analytic findings which also include depression as the predominant comorbidity. Recent multicentre studies comparing suicidal and non-suicidal MDD patients reported altered pattern of brain network organisation, particularly the fronto-limbic networks, more specifically related to suicide [74, 75]. Furthermore, using machine learning, STBs detection was primarily driven by the somatomotor network (SMN) while default mode network contributed to MDD identification [74], which further supports our proposal to incorporate the sensory system in the brain model of STBs. Previous machine learning studies have also reported structural and functional abnormalities within the SMN that were related to suicidal risk level [76, 77]. Nonetheless, given that majority of the STBs studies focused mainly on depression, it may be worthwhile for future empirical studies to examine STBs across a wider spectrum of psychiatric conditions (beyond mood disorders) within the same study. Fourth, there were not enough adolescent studies (<10 studies) for a separate subgroup analysis though the main findings remained in the subgroup analysis of adult samples. Thus, the findings should be interpreted cautiously for younger populations. All studies were cross-sectional, and hence the meta-analytic findings are still correlational. Lastly, the preliminary meta-analytic results may change in the future as more studies using whole-brain-analysis methods are available.

Conclusions

Results of the meta-analysis underscore the widespread involvement of the ventral fronto-limbic and visual-limbic-OFC and callosal body pathways in STBs. Diminished structural integrity of these circuitries may impede emotional regulation and sensory functioning thereby rendering the individual vulnerable to suicidal crisis. Insights into the neurobiological abnormalities associated with STBs are important as they encourage greater efforts to examine treatments to normalise these morphological alterations and reduce suicide deaths.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

WHO. World Health Statistics 2019: Monitoring Health for the SDGs. 2019.

Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143:187–232.

Auerbach RP, Pagliaccio D, Allison GO, Alqueza KL, Alonso MF. Neural correlates associated with suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury in youth. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89:119–33.

Schmaal L, van Harmelen A-L, Chatzi V, Lippard ETC, Toenders YJ, Averill LA, et al. Imaging suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A comprehensive review of 2 decades of neuroimaging studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:408–27.

Tian F, Wang X, Long X, Roberts N, Feng C, Yue S, et al. The correlation of reduced fractional anisotropy in the cingulum with suicide risk in bipolar disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:707622.

Catani M, Bambini V. A model for social communication and language evolution and development (SCALED). Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014;28:165–71.

Fields RD. White matter in learning, cognition and psychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:361–70.

Catani M. Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging tractography in cognitive disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;19:599–606.

Beaulieu C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system - a technical review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:435–55.

Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1487–505.

Johnston JAY, Wang F, Liu J, Blond BN, Wallace A, Liu J, et al. Multimodal neuroimaging of frontolimbic structure. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:667–75.

Wei S, Womer FY, Edmiston EK, Zhang R, Jiang X, Wu F, et al. Structural alterations associated with suicide attempts in major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;98:109827.

Fan S, Lippard ETC, Sankar A, Wallace A, Johnston JAY, Wang F, et al. Grey and white matter differences in adolescents and young adults with prior suicide attempts across bipolar and major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:1089–97.

Long Y, Ouyang X, Liu Z, Chen X, Hu X, Lee E, et al. Associations among suicidal ideation, white matter integrity and cognitive deficit in first-episode schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:391.

Vandeloo KL, Burhunduli P, Bouix S, Owsia K, Cho KIK, Fang Z, et al. Free-water diffusion magnetic resonance imaging differentiates suicidal ideation from suicide attempt in treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2023;8:471–81.

Westlund Schreiner M, Mueller BA, Klimes-Dougan B, Begnel ED, Fiecas M, Hill D, et al. White matter microstructure in adolescents and young adults with non-suicidal self-Injury. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:1019.

Lee SJ, Kim B, Oh D, Kim MK, Kim KH, Bang SY, et al. White matter alterations associated with suicide in patients with schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2016;248:23–9.

Lippard ETC, Johnston JAY, Spencer L, Quatrano S, Fan S, Sankar A, et al. Preliminary examination of grey and white matter structure and longitudinal structural changes in frontal systems associated with future suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults with mood disorders. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:1139–48.

Chen G, Hu X, Li L, Huang X, Lui S, Kuang W, et al. Disorganisation of white matter architecture in major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging with tract-based spatial statistics. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21825.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12.

Radua J, Mataix-Cols D. Meta-analytic methods for neuroimaging data explained. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2012;2:6.

Radua J, Rubia K, Canales-Rodriguez EJ, Pomarol-Clotet E, Fusar-Poli P, Mataix-Cols D. Anisotropic kernels for coordinate-based meta-analyses of neuroimaging studies. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:13.

Peters BD, Szeszko PR, Radua J, Ikuta T, Gruner P, DeRosse P, et al. White matter development in adolescence: diffusion tensor imaging and meta-analytic results. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:1308–17.

Radua J, Mataix-Cols D. Voxel-wise meta-analysis of grey matter changes in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:393–402.

Oquendo MA, Halberstam B, Mann JJ. Chapter 4. risk factors for suicidal behavior: the utility and limitations of research instruments. : Standardized evaluation Clin Pract: Rev psychiatry. 2024;22:103–30.

Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, et al. The columbia-suicide severity rating scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–77.

Addington J, Shah H, Liu L, Addington D. Reliability and validity of the calgary depression scale for schizophrenia (CDSS) in youth at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2014;153:64–7.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33.

Vieira R, Faria AR, Ribeiro D, Picó-Pérez M, Bessa JM. Structural and functional brain correlates of suicidal ideation and behaviors in depression: a scoping review of MRI studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2023;126:110799.

Coad BM, Postans M, Hodgetts CJ, Muhlert N, Graham KS, Lawrence AD. Structural connections support emotional connections: uncinate fasciculus microstructure is related to the ability to decode facial emotion expressions. Neuropsychologia. 2020;145:106562.

O’ Brien S, Sethi A, Blair J, Viding E, Beyh A, Mehta MA, et al. Rapid white matter changes in children with conduct problems during a parenting intervention. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:339.

Colic L, Villa LM, Dauvermann MR, van Velzen LS, Sankar A, Goldman DA, et al. Brain grey and white matter structural associations with future suicidal ideation and behaviors in adolescent and young adult females with mood disorders. JCPP Adv. 2022;2:e12118.

Szebeni A, Szebeni K, DiPeri T, Chandley MJ, Crawford JD, Stockmeier CA, et al. Shortened telomere length in white matter oligodendrocytes in major depression: Potential role of oxidative stress. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:1579–89.

Catani M, Thiebaut De Schotten M. Atlas of Human Brain Connections. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012.

Dalgleish T. The emotional brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:583–9.

Kim JJ, Diamond DM. The stressed hippocampus, synaptic plasticity and lost memories. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:453–62.

Savransky A, Chiappelli J, Rowland LM, Wisner K, Shukla DK, Kochunov P, et al. Fornix structural connectivity and allostatic load: Empirical evidence from schizophrenia patients and healthy controls. Psychosom Med. 2017;79:770–6.

Nugent KL, Chiappelli J, Sampath H, Rowland LM, Thangavelu K, Davis B, et al. Cortisol reactivity to stress and its association with white matter integrity in adults with schizophrenia. Psychosom Med. 2015;77:733–42.

Lim L, Howells H, Radua J, Rubia K. Aberrant structural connectivity in childhood maltreatment: a meta-analysis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2020;116:406–14.

Benear SL, Ngo CT, Olson IR. Dissecting the fornix in basic memory processes and neuropsychiatric disease: a review. Brain Connect. 2020;10:331–54.

Richard-Devantoy S, Berlim MT, Jollant F. Suicidal behaviour and memory: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16:544–66.

Hu S, Mo D, Guo P, Zheng H, Jiang X, Zhong H. Correlation between suicidal ideation and emotional memory in adolescents with depressive disorder. Sci Rep. 2022;12:5470.

Vandekerckhove M. Neural networks in bottom up ‘experiential emotion regulation. Behav Brain Res. 2020;383:111242.

Lima Santos JP, Brent D, Bertocci M, Mailliard S, Bebko G, Goldstein T, et al. White matter correlates of suicidality in adults with bipolar disorder who have been prospectively characterized since childhood. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021;6:107–16.

Hu C, Jiang W, Wu Y, Wang M, Lin J, Chen S, et al. Microstructural abnormalities of white matter in the cingulum bundle of adolescents with major depression and non-suicidal self-injury. Psychol Med. 2024;54:1113–21.

Paul LK, Pazienza SR, Brown WS. Alexithymia and somatization in agenesis of the corpus callosum. Soc Cog Affect Neurosci. 2021;16:1071–8.

Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behaviour. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:885–90.

Lanteri P, Serio I, Aurigo A, Rebora S, Chiorri C, Garbarino S, et al. psychopathology and patterns of sensory processing in non-suicidal self-injured adolescents: insights from neuropsychological and neurophysiological studies. Neuropsychiatry. 2019;9:2308–16.

Cyprien F, de Champfleur NM, Deverdun J, Olié E, Le Bars E, Bonafé A, et al. Corpus callosum integrity is affected by mood disorders and also by the suicide attempt history: A diffusion tensor imaging study. J Affect Disord. 2016;206:115–24.

Zhang R, Jiang X, Chang M, Wei S, Tang Y, Wang F. White matter abnormalities of corpus callosum in patients with bipolar disorder and suicidal ideation. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2019;18:20.

Bucker J, Muralidharan K, Torres IJ, Su W, Kozicky J, Silveira LE, et al. Childhood maltreatment and corpus callosum volume in recently diagnosed patients with bipolar i disorder: data from the systematic treatment optimization program for early mania (STOP-EM). J Psychiatr Res. 2014;48:65–72.

Teicher MH, Dumont NL, Ito Y, Vaituzis C, Giedd JN, Andersen SL. Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:80–5.

Catani M, Jones DK, Donato R, Ffytche DH. Occipito-temporal connections in the human brain. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 9):2093–107.

Kim B, Oh J, Kim MK, Lee S, Tae WS, Kim CM, et al. White matter alterations are associated with suicide attempt in patients with panic disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:139–46.

Reis JV, Vieira R, Portugal-Nunes C, Coelho A, Magalhães R, Moreira P, et al. Suicidal ideation is associated with reduced functional connectivity and white matter integrity in drug-naïve patients with major depression. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:838111.

Tymofiyeva O, Reeves KW, Shaw C, Lopez E, Aziz S, Max JE, et al. A systematic review of MRI studies and the “Emotional paiN and social disconnect (END)” brain model of suicidal behaviour in youth. Behav Neurol. 2023;2023:7254574.

Mann JJ, Rizk MM. A brain-centric model of suicidal behaviour. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:902–16.

Weng JC, Chou YS, Tsai YH, Lee CT, Hsieh MH, Chen VC. Connectome analysis of brain functional network alterations in depressive patients with suicidal attempt. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1966.

Wagner G, de la Cruz F, Köhler S, Pereira F, Richard-Devantoy S, Turecki G, et al. Connectomics-based functional network alterations in both depressed patients with suicidal behaviour and healthy relatives of suicide victims. Sci Rep. 2019;9:14330.

Greicius MD, Supekar K, Menon V, Dougherty RF. Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:72–8.

Lenroot RK, Giedd JN. The changing impact of genes and environment on brain development during childhood and adolescence: initial findings from a neuroimaging study of pediatric twins. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:1161–75.

Fuller-Thomson E, Baird SL, Dhrodia R, Brennenstuhl S. The association between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and suicide attempts in a population-based study. Child Care Health Dev. 2016;42:725–34.

Flinkenflügel K, Meinert S, Thiel K, Winter A, Goltermann J, Strathausen L, et al. Negative stressful life events and social support are associated with white matter integrity in depressed patients and healthy control participants: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2023;94:650–60.

Lim L, Radua J, Rubia K. Grey matter Abnormalities in childhood maltreatment: A voxel-wise meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:854–63.

Lebel C, Gee M, Camicioli R, Wieler M, Martin W, Beaulieu C. Diffusion tensor imaging of white matter tract evolution over the lifespan. Neuroimage. 2012;60:340–52.

Owens SA, Eisenlohr-Moul T. Suicide risk and the menstrual cycle: A review of candidate RDoC mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:106.

Osborn E, Brooks J, O’Brien PMS, Wittkowski A. Suicidality in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: A systematic literature review. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2021;24:173–84.

Lambert HK, King KM, Monahan KC, McLaughlin KA. Differential associations of threat and deprivation with emotion regulation and cognitive control in adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2017;29:929–40.

Poletti S, Melloni E, Mazza E, Vai B, Benedetti F. Gender-specific differences in white matter microstructure in healthy adults exposed to mild stress. Stress. 2020;23:116–24.

Mohammadi S, Seyedmirzaei H, Salehi MA, Jahanshahi A, Zakavi SS, Dehghani Firouzabadi F, et al. Brain-based sex differences in depression: a systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Brain Imaging Behav. 2023;17:541–69.

Vetter JS, Spiller TR, Cathomas F, Robinaugh D, Brühl A, Boeker H, et al. Sex differences in depressive symptoms and their networks in a treatment-seeking population – A cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:357–64.

Li S, Zhang X, Cai Y, Zheng L, Pang H, Lou L. Sex difference in incidence of major depressive disorder: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2023;22:53.

Cho SS, Pellecchia G, Ko JH, Ray N, Obeso I, Houle S, et al. Effect of continuous theta burst stimulation of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on cerebral blood flow changes during decision making. Brain Stimul. 2012;5:116–23.

Qin K, Li H, Zhang H, Yin L, Wu B, Pan N, et al. Transcriptional patterns of brain structural covariance network abnormalities associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviours in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2024;96:435–44.

Li H, Zhang H, Qin K, Yin L, Chen Z, Zhang F, et al. Disrupted small-world white matter networks in patients with major depression and recent suicide plans or attempts. Brain Imaging Behav. 2024;18:741–52.

Chen S, Zhang X, Lin S, Zhang Y, Xu Z, Li Y, et al. Suicide risk stratification among major depressed patients based on a machine learning approach and whole-brain functional connectivity. J Affect Disord. 2023;322:173–9.

Hu J, Huang Y, Zhang X, Liao B, Hou G, Xu Z, et al. Identifying suicide attempts, ideation, and non-ideation in major depressive disorder from structural MRI data using deep learning. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;82:103511.

Jia Z, Huang X, Wu Q, Zhang T, Lui S, Zhang J, et al. High-field magnetic resonance imaging of suicidality in patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1381–90.

Mahon K, Burdick KE, Wu J, Ardekani BA, Szeszko PR. Relationship between suicidality and impulsivity in bipolar I disorder: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:80–9.

Olvet DM, Peruzzo D, Thapa-Chhetry B, Sublette ME, Sullivan GM, Oquendo MA, et al. A diffusion tensor imaging study of suicide attempters. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;51:60–67.

Taylor WD, Boyd B, McQuoid DR, Kudra K, Saleh A, MacFall JR. Widespread white matter but focal grey matter alterations in depressed individuals with thoughts of death. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015;62:22–28.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by A*STAR (SICS EPI Grant). JR is currently supported by Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation Grant No. PI22/00261, integrated into the Plan Nacional de I + D + I and co-financed by ERDF Funds from the European Commission (“A Way of Making Europe”) and CERCA Program/Generalitat de Catalunya and Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia I Coneixement Grant No. 2021 SGR 01128. The views expressed are those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. JR and AB analysed the data. All authors contributed to manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

LL, JR and AB reported no financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, L., Radua, J. & Beyh, A. Structural connectivity abnormalities in suicidal thoughts and behaviours: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry 15, 480 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03699-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03699-4