Abstract

The cerebral cortex provides the main input to the striatum, constituting the first step in cortico-basal ganglia loops. Decades of careful anatomical tract-tracing research have established the exquisite topography of each cortical region’s projection to the striatum in nonhuman primates. In parallel, neuroimaging research has demonstrated the relationship between cortico-striatal resting-state functional connectivity and specific cognitive, behavioral, psychiatric, and neurological states in humans. However, still unclear is the extent to which functional connectivity recapitulates the specific topographies of cortico-striatal anatomical connectivity. Here, we combined datasets of cortico-striatal anatomical and functional connectivity in macaques to determine the degree of overlap between the two. Across multiple metrics of similarity, we found that anatomical and functional connectivity demonstrated higher correspondence in the frontal and primary somatosensory cortices, with lower correspondence in other brain regions. This suggests that there are many regions in the brain in which cortico-striatal functional connectivity may not be driven by direct anatomical connectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The gateway to the basal ganglia, the striatum is involved in a diverse array of functions, ranging from motivation and emotion to cognition and motor control [1,2,3,4]. Numerous anatomical tract-tracing studies have demonstrated that the projection to the striatum from the cerebral cortex is both highly topographic (meaning each cortical region has a unique projection pattern) and overlapping (meaning striatal projections from differing cortical regions can overlap in their territories) (e.g., [5,6,7,8,9]). These topographic and overlapping projections are thought to subserve the diverse and integrative functions of cortico-basal ganglia loops.

Cortico-striatal functional connectivity, as measured with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), has proved useful in characterizing many brain disorders (e.g., [10,11,12]). These studies show that each disorder has a unique, altered connectivity fingerprint, as might be expected if the connections between a subset of cortical regions have impaired connectivity with their distinct striatal target zones. For example, patients with Parkinson’s Disease show reduced functional connectivity between the posterior putamen and the somatosensory cortex but enhanced functional connectivity between the anterior putamen and the inferior parietal cortex [13]. Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have greater functional connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the caudate nucleus [14]. Depressed patients have reduced ventromedial prefrontal cortex - ventral striatal functional connectivity and enhanced dorsolateral prefrontal cortex - dorsal striatal functional connectivity [15].

Furthermore, functional connectivity within distinct cortico-striatal circuits has been successfully linked to specific cognitive and emotional processes in healthy brains (e.g., [16,17,18]. For example, functional connectivity between the caudate and cortical oculomotor regions correlates with the impact of motivation on oculomotor control [19]. Functional connectivity between the posterior putamen and sensorimotor cortices strengthens as humans learn to navigate a virtual maze [20]. Functional connectivity of anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices with the ventral striatum varies with the impact of reward on memory performance [21].

Functional connectivity has also been used to group cortical regions into networks, such as the default mode network, the salience network, and the frontoparietal network [22]. Fluctuations and perturbations in these networks are uniquely associated with specific brain disorders and cognitive, behavioral, and emotional processes. Each cortical network, in turn, appears to have a distinct pattern of functional connectivity with the striatum. For example, the limbic network functionally connects with the rostral ventral striatum; the frontoparietal control network and default mode network functionally connect with different portions of the caudate and ventral putamen [23].

All of these studies–on health, disease, and relationships to cortical networks–emphasize the importance of cortico-striatal functional connectivity. However, they do not explain its underlying biological framework. Still, cortico-striatal patterns of functional connectivity appear to recapitulate the complex topographies of anatomical connectivity as measured with tract-tracing. For example, in humans, a seed placed in the dorsal caudate functionally connects with the lateral prefrontal cortex, while a seed placed in the ventral striatum connects with the orbitofrontal cortex [24], reflecting known anatomical connections in monkeys and rodents [5, 7, 25]. Similarly, human medial orbitofrontal cortex functionally connects with the central and ventromedial portions of the rostral striatum, while the lateral orbitofrontal cortex functionally connects with the central and dorsal parts of the rostral striatum, mirroring the overlapping topographies observed in anatomical connectivity in nonhuman primates [26]. At an even finer-grained level, foot vs tongue representations of the human motor cortex functionally connect with dorsal vs ventral putamen, a pattern also seen in monkey tract-tracing [23, 27]. Many of these patterns are also recapitulated using diffusion tractography [28].

Despite the wealth of information on cortico-striatal functional connectivity, the degree to which it reflects underlying anatomical connectivity has only been qualitatively, rather than quantitatively, assessed [23, 29, 30]. Part of this is due to study species: most studies of resting-state cortico-striatal functional connectivity have been performed in humans, in whom tract-tracing is not possible. Thus, functional connectivity in humans is compared to tract-tracing in nonhuman animals, confounding claims of match vs mismatch [23, 29]. Therefore, here, we both quantitatively and qualitatively compared resting-state cortico-striatal functional connectivity to anatomical connectivity, both within macaques. Another potential issue is differences across brain regions: most comparisons have been performed using a small sampling of brain regions. However, nearly the entire cerebral cortex projects to the striatum. Furthermore, the qualitative nature of the observations may have limited the ability to discern differences across regions in multimodal connectivity overlap [30]. Thus, we wanted to know whether the relationship between anatomical and functional connectivity would differ based on the specific cortical brain region.

Prior work quantitatively characterizing the relationship between functional and anatomical connectivity has not focused on cortico-striatal circuits. It has, however, highlighted that 1:1 relationships between these two types of connectivity are rare. In one analysis in marmosets (which did not include cortico-striatal connectivity), the correlation between functional and anatomical connectivity was moderate at short distances (r = 0.45), but disappeared at long distances (r = -0.031) [31]. Functional and anatomical cortico-cortical connectivity in macaques are moderately correlated [32], and these correlations increase with stronger connectivity values [33]. Based on these findings, we did not expect that cortico-striatal anatomical and functional connectivity would necessarily show perfect correspondence.

Methods

fMRI

FMRI data collection procedures were described in detail previously in [34, 35]. Subjects were 9 macaques (mixed Macaca fascicularis and mulatta; 6 females and 3 males). Procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All subjects were fed ad libitum and pair-housed within a light and temperature-controlled colony room. Animals were not water restricted. None of the subjects had any prior implant or cranial surgery. Animals were fasted for 14–16 h prior to imaging.

On scanning days, anesthesia was first induced by intramuscular injection of ketamine hydrochloride (7.5 mg/kg) and dexmedetomidine (13 µg/kg). Subjects were transported to the scanner anteroom and intubated using an endotracheal tube. Initial anesthesia was maintained using 1.0–2% isoflurane mixed with oxygen (1 L/m during intubation and 2 L/m during scanning to compensate for the 12-m length of the tubing used). For functional imaging, the isoflurane level was lowered to <=1%.

Subjects were placed onto a custom-built coil bed with integrated head fixation by placing stereotactic ear bars into the ear canals [36]. The position of the animal corresponds to the sphinx position. Experiments were performed with animals freely breathing. An initial bolus injection of 1.5 µg/kg fentanyl was administered IV followed by a continuous administration of 3 µg/kg/hr using a syringe pump. Rectal temperature ( ~ 99.6 F), respiration (10–15 breaths/min), end-tidal CO2 (25–40), electrocardiogram (70–150 bpm), and SpO2 (>90%) were monitored using an MRI compatible monitor (IRADIMED 3880 MRI Monitor, USA). Temperature was maintained using a circulating water bath as well as chemical heating pads and padding for thermal insulation.

Data were acquired on a passively shielded 10.5 T, 88-cm diameter clear bore magnet coupled to Siemens gradients (‘SC72’ body gradients operating at a slew rate of 200 mT/m/s, and 70 mT/m maximal strength), and electronics (Magnetom 10.5 T Plus) (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Within the gradient set and the bore-liner, the space available for subject insertion had a 60-cm diameter.

The 10.5-T system operates on the E-line (E12U) platform which is directly comparable to clinical platforms (3 T Prisma/Skyra, 7 T Terra). As such, the user interface and pulse sequences were identical to those running on clinical platforms. A custom in-house built and designed RF coil with an 8-channel transmit/receive end-loaded dipole array of 18-cm length (individually) combined with a close-fitting 16-channel loop receive array head cap, and an 8-channel loop receive array of 50 × 100 mm2 size located under the chin [36]. The size of 14 individual receive loops of the head cap was 37 mm with two larger ear loops of 80 mm—all receiver loops were arranged in an overlapping configuration for nearest neighbor decoupling. The resulting combined 32 receive channels were used for all experiments and supported threefold acceleration in phase encoding direction. The coil holder was designed to be a semi-stereotaxic instrument holding the head of the animal in a centered sphinx position via customized ear bars. The receive elements were modeled to adhere as close to the surface of the animal’s skulls as possible. Transmit phases for the individual transmit channels were fine-tuned for excitation uniformity for one representative mid-sized animal and the calculated phases were then used for all subsequent acquisitions. Magnetic field homogenization (B0 shimming) was performed using a customized field of view with the Siemens internal 3D mapping routines. Multiple iterations of the shims (using the adjusted FOV shim parameters) were performed, and further fine adjustment was performed manually on each animal. Third-order shim elements were ignored for these procedures.

In all animals, a B1+ (transmit B1) fieldmap was acquired using a vendor provided flip angle mapping sequence and then power calibrated for each individual. Following B1+ transmit calibration, 3–5 averages (23 min) of a T1 weighted magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo protocol (3D MP-RAGE) were acquired for anatomical processing (TR = 3300 ms, TE = 3.56 ms, TI = 1140 ms, flip angle=5°, slices=256, matrix=320 × 260, acquisition voxel size=0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm3). Images were acquired using in-plane acceleration GRAPPA = 2. A resolution and FOV matched T2 weighted 3D turbo spin-echo sequence (variable flip angle) was run to facilitate B1 inhomogeneity correction.

Before the start of the functional data acquisition, five images were acquired in both phase-encoding directions (R/L and L/R) for offline EPI distortion correction. Five to six runs of fMRI time series, each consisting of 700 continuous 2D multiband (MB)/Simultaneous Multi Slice (SMS) EPI [37,38,39] functional volumes (TR = 1110 ms; TE = 17.6 ms; flip angle=60°, slices=58, matrix=108 × 154; FOV = 81 × 115.5 mm2; acquisition voxel size=0.75 × 0.75 × 0.75 mm2) were acquired. Images were acquired with a left-right phase encoding direction using in plane acceleration factor GRAPPA = 3, partial Fourier=7/8th, and MB or simultaneous multislice factor=2 (i.e., the number of simultaneously excited slices=2). Since macaques were scanned in sphinx positions, the orientations noted here are what is consistent with a (headfirst supine) typical human brain study (in terms of gradients) but translate differently to the actual macaque orientation.

Image processing was performed using a custom pipeline relying on FSL [40], ANTs [41, 42], AFNI [43], and a heavily modified CONN [44] toolbox. Images were first motion corrected using mcflirt (registration to the first image). Motion parameters never exceeded 0.5 mm or 0.4° rotation except in one run of one animal, which was discarded (the animal experienced anesthesia-induced emesis during the last run). Images were slice-time corrected and EPI distortion corrected using topup. High magnetic fields and large matrix sizes are commonly associated with severe EPI distortions. Anatomical images were nonlinearly warped into the ‘National Institute of Mental Health Macaque Template’ (NMT v2.0) [45] template using ANTs and 3DQwarp in AFNI. The distortion correction, motion correction, and normalization were performed using a single sinc interpolation. Functional images were spatially smoothed (FWHM = 2 mm), linear detrended, denoised using a linear regression approach including heart rate and respiration, as well as a five-component nuisance regressor of the masked white matter and cerebrospinal fluid and band-pass filtering (0.008–0.09 Hz) [46]. The functional images were then warped into the same NMT v2.0 template using ANTs and 3DQwarp in AFNI.

Tract-tracing

Cortico-striatal tract-tracing data were drawn from two sources: the literature and tissue from the Heilbronner Lab. For both sources, injection sites and dense striatal terminations for each case were registered to the NMT v1.2 standard space for comparison with fMRI [47].

In total, there were 88 cases, with each case representing the injection of a single anterograde or bidirectional tract-tracer into the macaque brain and resulting striatal terminal field label. This number was necessary to sufficiently tile the macaque cerebral cortex.

Cases from Heilbronner Lab

We injected tract-tracers into the cerebral cortex of 7 adult macaque subjects (6 males, 1 female, all Macaca mulatta). Prior to surgery, anatomical T1 and T2-weighted MRIs were obtained at University of Minnesota’s Center for Magnetic Resonance Research. Stereotaxic earbars were filled with Vitamin E solution to visualize on the MRI and guide tracer placement relative to stereotaxic zero. Only one subject from this cohort was also part of the rs-fMRI cohort, precluding within-subjects analyses.

On the day of surgery, monkeys were tranquilized by intramusculuar injections of ketamine (10 mg/kg), midazolam (0.25 mg/kg) and atropine (0.04 mg/kg). A surgical plane of anesthesia was then maintained via the administration of inhalation of isofluorane (1–3%). Monkeys were placed in a stereotaxic instrument (Kopf Instruments), a midline scalp incision was made, and the muscle and fascia were displaced laterally to expose the skull. A craniotomy ( ~ 2–3 cm2) was made over the area of interest, and small dural incisions were made only at injection sites. Monkeys received injections of fluororuby (FR, 50 nl, 10% in 0.1 M PB, pH 7.4, Invitrogen) or AAV5-CaMKII-hM4Di-mCherry (1.25 * 1014, 20 ul) into the cerebral cortex. (Additional injections of other tracers were performed in some animals, in other regions. These do not cross-react with FR and were made distant from the sites described here). Tracers were pressure-injected over 10 min using Hamilton syringe. Following each injection, the syringe remained in situ for 5–20 min. Twelve to 14 days (FR) or 131 days (AAV) after surgery, monkeys were again deeply anesthetized and perfused with 4 L of saline followed by 6 L of a 4% paraformaldehyde/1.5% sucrose solution in 0.1 M PB, pH 7.4. Brains were postfixed overnight and cryoprotected in increasing gradients of sucrose (10, 20, and 30%). Serial sections of 50 μm were cut on a freezing microtome into cryoprotectant solution.

One in eight sections was processed free-floating for immunocytochemistry to visualize the tracer. Tissue was incubated in primary anti-FR (1:6000; Invitrogen) or primary anti-mCherry antibody (1:1000 Abcam) in 10% NGS and 0.3% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PO4 for 4 nights at 4 °C. After extensive rinsing, the tissue was incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody followed by incubation with the avidin-biotin complex solution (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Laboratories). Immunoreactivity was visualized using standard DAB procedures. Staining was intensified by incubating the tissue for 5–15 s in a solution of 0.05% DAB tetrahydrochloride, 0.025% cobalt chloride, 0.02% nickel ammonium sulfate, and 0.01% H2O2. Sections were mounted onto gel-coated slides, dehydrated, defatted in xylene, and coverslipped with Permount.

Using a Zeiss M2 AxioImager, light microscopy was used to outline brain sections, injection sites and striatal terminal fields on 1 in 24 sections (1.2 mm apart). Terminal fields were outlined in darkfield using a 2.0, 4.0, or 10× objective with Neurolucida software (MicroBrightField Bioscience). Terminal fields were considered dense when they could be visualized at a low objective (2.0×); otherwise, terminal fields were considered sparse. Thin, labeled fibers containing boutons were marked as terminating; thick fibers without boutons were considered passing.

Archival cases

Cases drawn from the literature were from adult animals (Macaca mulatta, fascicularis, arctoides, and nemestrina), with well-confined injection sites without white matter contamination, and where figures included the original charts of anterograde striatal labeling and photomicrographs or diagrams of the injection site [6, 7, 25, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. As in our prior work [61, 62], the locations of dense striatal terminal fields and injection sites were determined using provided figures and textual descriptions, then incorporated on the appropriate section in the reference model. For full methods from cases in the literature, see the corresponding articles in Fig. 1.

A summary of tract-tracing cases categorized by source publication and the targeted brain region. Each bar represents the number of cases reported by a given study or lab, with colors indicating the specific brain region involved. A total of 88 cases were included. Registered tract-tracing and matched, averaged resting-state functional connectivity MRI (rs-fcMRI) data can be downloaded from https://github.com/srheilbronner/corticostriatal.

Analysis

Tract-tracing data registration

Cases were registered and rendered in 3D in the following way. For each case, a stack of 2D coronal sections was created from its Neurolucida chartings. This stack was imported into IMOD (Boulder Laboratory for 3D Electron Microscopy), and a 3D reconstruction that contained the injection sites, dense terminal fields, and cells was created for each case separately. To render these and merge cases together, we used a reference model from the NIMH Macaque Template (NMT v1.2), imported into IMOD. Placement of all contours—injection sites, dense terminal fields, area outlines—were assessed according to cortical and subcortical landmarks in the brain, then checked with the original case and corrected as needed.

Functional connectivity

Functional connectivity was computed following these steps: 1) We extracted the coordinates of the injection site contours from IMOD and created binary masks in the NMT v1.2 MRI space. 2) The injection site masks were then registered to the NMT v2.0 fMRI space. In each monkey, BOLD time series were extracted from each mask and averaged across voxels as the seed time series. 3) For injection site, in each monkey and within each run, Pearson’s correlation was computed between the seed time series and the BOLD time series of every voxel in the striatum, with the region of striatum defined by the SARM atlas (level 4 parcellation, [63]). The correlation scores then underwent Fisher’s z transformation and were averaged across runs, resulting in one functional connectivity volume for each injection and each monkey.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, cases were classified as belonging to the frontal (including anterior cingulate), associative parietal (including posterior cingulate), primary somatosensory, insula, extrastriate visual, and temporal cortical areas.

We completed several analyses to quantify the relationship between functional and anatomical connectivity. The first metric of interest was the Dice coefficient for the overlap between functional and anatomical connectivity. For this, we registered the functional connectivity volumes to the NMT v1.2 space for computing the Dice coefficients. We focus on positive Pearson’s correlation here for assessing the overlap with tract-tracing data (dense terminal fields). It is possible that direct anatomical connectivity results in strong negative correlations of BOLD activity. We differentiate this scenario from that with positive BOLD correlations, as the latter was mainly observed with the frontal cortex, and we would like the Dice coefficient to preserve this region-specificity).

To compute the Dice coefficient, we binarized the functional connectivity with a stability-justified threshold (the justification is detailed below) and applied the following formula to each injection site and each monkey:

where Nb is the number of voxels covered by tract-tracing terminal fields in which functional connectivity was positive, Nfc is the total number of voxels with positive functional connectivity, and Ntt is the total number of voxels covered by tract-tracing dense terminal fields. To determine the threshold for functional connectivity, we tested the stability of Dice coefficients over gradually changing thresholds by percentile, calculated over the pooled functional connectivity of all the cases and monkeys. Across cases and monkeys, the Dice coefficient stayed at a consistent level before showing steady decrease at thresholds between the 40th and 25th percentiles. We chose the value of the 25th percentile as the fixed threshold for computing the Dice coefficient, following the rationale that it selects the strongest quarter of functional connectivity for comparing with the tract-tracing data, while lowering this threshold would not substantially affect the degree of their overlap (the average Dice coefficient dropped by ~6% from the 40th- to the 25th-percentile thresholding).

Importantly, comparisons for each case were only performed on those coronal slices for which there was associated tract-tracing data, such that missing data was not misinterpreted as a lack of connection. Terminal field size (normalized by number of available sections) was related to cortical brain region (Kruskal Wallis F(5, 82) = 13.62, p = 0.018). Post-hoc Dunn analyses revealed that this was mainly due to small terminal fields following parietal injections, with the comparison between parietal and frontal the only one achieving significance (p = 0.01). Because we were concerned that terminal field size could vary across cortical region, biasing the Dice coefficient, we used a random sampling procedure to control for size. For each of the terminal fields except the smallest one, we randomly sampled a subset of voxels (without replacement) to match the size of the smallest terminal field. We then computed the Dice coefficients based on the sampled voxels. The mean Dice coefficient over 100 random samples was computed for each case and each monkey.

Second, we asked about differences in functional connectivity inside of the anatomical terminal field vs outside of the anatomical terminal field, again taking only those coronal sections with data provided into account.

Finally, we evaluated functional and anatomical connectivity with the three major divisions of the striatum (caudate, putamen, nucleus accumbens). Using NMT SARM subdivisions, we determined the average functional connectivity within each nucleus, for each case and monkey separately. Next, we quantified the size of the terminal field within each nucleus for each case, normalized by the size of the nucleus. We averaged functional connectivity across monkeys to obtain one value for each case.

Results

Overview

We qualitatively and quantitatively compared the degree of overlap between functional and anatomical connectivity for six categories of macaque cerebral cortical brain areas (frontal, parietal, extrastriate, temporal, somatosensory, and insular cortices) with the striatum. Both types of cortico-striatal projection patterns were both highly topographically unique to the specific region and overlapping across regions.

Frontal cases (Fig. 2A). Frontal anatomical connectivity with the striatum was highly differentiable based on the region injected, as previously described [6, 7, 25]. However, these are not randomly distributed by region, but are highly topographic according to relative location in the cerebral cortex [64]. Consistent with prior reports, a similar pattern could be observed in the cortico-striatal functional connectivity results, with more ventral and medial frontal cortical injection sites projecting ventrally and medially within the striatum from dorsal and lateral frontal cortical injection sites. Thus, there was often high concordance between anatomical and functional connectivity.

White outline indicates area of dense terminal field labeling following an injection in the region listed. Functional connectivity from a matching seed is shown in heat map form. A Frontal cases from [25] (i), [7] (ii), and [6] (iii). B Somatosensory cases from [54] (i-iii). C Insular cases from [52] (i), [49] (ii), and [6] (iii).

Somatosensory cases(Fig. 2B). Projections from the primary somatosensory cortex are distributed along the anterior-posterior extent of the putamen, particularly its lateral half [54]. Functional connectivity appeared to largely preserve this pattern.

Insular cases (Fig. 2C). Like the frontal cortex projection to the striatum, the insular cortical projection to the striatum is topographic according to area of origin. Posterior and dorsal parts of the insula (which are granular) project dorsolaterally within the striatum, while anterior and ventral parts of the insula (which are agranular/dysgranular) project ventromedially within the striatum [49]. Functional connectivity was largely consistent with this pattern, although there was often excessive connectivity with the lateral putamen, potentially because of its position close to the insular cortex.

Temporal cases (Fig. 3A). As detailed in [48, 50, 59, 60], temporal cortex anatomical projections span both the dorsal and ventral striatum, with differences according to region of origin. The temporal pole projects to the ventromedial striatum; area TE projects to ventrolateral striatum as well as caudal caudate. Projections from the medial temporal lobe split, such that the same injection resulted in terminals in both the ventral striatum and the dorsal caudate. Projections from the superior temporal gyrus are mainly to the central striatum, with some regions also projecting ventrally or dorsally. In some cases, functional connectivity from these regions appears to be largely unrelated to patterns of anatomical connectivity. For example, a seed placed to match an injection in the temporal pole results in widespread functional connectivity throughout the central striatum, whereas anatomical connectivity is confined to the ventromedial striatum. However, in other cases, there were remarkable patterns of overlap. A seed matched to an injection site in inferior temporal cortex was able to match the observed anatomical connectivity to the caudal caudate and ventral putamen.

White outline indicates area of dense terminal field labeling following an injection in the region listed. Functional connectivity from a matching seed is shown in heat map form. A Temporal cases from [60] (i-iii) B Parietal cases from Heilbronner Laboratory (i), [48] (ii), and [58] (iii). C Extrastriate cases from [59] (i-ii).

Associative parietal cases (Fig. 3B). Anatomical connectivity from the parietal cortex is largely with the dorsal striatum. Projections from posterior cingulate cortex, for example, mainly terminate in a band along the dorsalmost portion of the caudate nucleus. Projections from the inferior parietal lobule extend slightly ventral to this point, but are still inside the dorsal caudate [51, 58]. Functional connectivity patterns were quite different. For example, a seed in the posterior cingulate cortex resulted in functional connectivity with the ventral striatum, but not with the dorsal caudate (which showed negative functional connectivity values).

Extrastriate visual cases (Fig. 3C). As detailed in [59], anatomical projections from extrastriate cortical regions terminate mainly in the dorsal caudate and putamen, particularly the lateral sector of the caudate and the caudal putamen. Seeds placed in extrastriate regions seemed to result in functional connectivity largely unrelated to the observed anatomical connectivity. Much of the extrastriate-striatal functional connectivity was negative in nature, making it challenging to interpret. However, there were areas of positive connectivity, but these seemed to be in different zones than the anatomical projections.

Quantitative comparison of anatomical vs functional connectivity

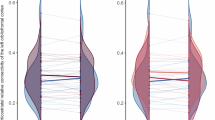

We were interested in whether the overlap between anatomical and functional connectivity, measured by the Dice coefficient, differed according to cortical regions. We first verified that the Dice coefficients across animals followed a non-normal distribution by performing an Anderson-Darling test for normality. The null hypothesis that residuals are normally distributed was rejected. Thus, we used aligned-rank transformation (ART) ANOVA [65], a non-parametric alternative to repeated measures ANOVA to test for a within-subject fixed effect of cortical regions, treating animals (subjects) as a random effect. Indeed, ART ANOVA revealed a significant effect of region F(5, 82) = 14.2, p < 0.001 (Fig. 4A). After applying adjustment for multiple-comparisons, follow-up contrasts (Fig. 4B) suggest that sites can be categorized into three groups: 1) frontal, insula and somatosensory, 2) extrastriate and parietal, and 3) temporal. Sites in group 1 show significant contrasts with sites in group 2, with a greater mean Dice coefficient in group 1. Visualization of the Dice coefficient on the cortical surface across injection sites showed a consistent pattern with the suggested grouping (Fig. 4C).

A Boxplot of Dice coefficients according to brain region. Black dots mark the outliers beyond three times the distance from the upper quartile (upper edge of the box) to the median (middle line in each box). B Post hoc contrasts between sites. C Visualization of Dice coefficient for corresponding injection site/ROI on an inflated surface of the NMT template.

We next wanted to know whether there were differences in functional connectivity inside vs outside of the terminal fields according to cortical region of origins. We first verified that the difference between functional connectivity values in vs out of the terminal field followed a non-normal distribution by performing an Anderson-Darling test for normality. The null hypothesis that residuals are normally distributed was rejected. ART ANOVA revealed a significant effect of region F(5, 82) = 6.12, p < 0.001 (Fig. 5A). After applying adjustment for multiple-comparisons, follow-up contrasts (Fig. 5B, C) suggest that somatosensory and frontal cortices have greater differences in functional connectivity inside vs outside their anatomical terminal field than other regions.

A Boxplot of functional connectivity difference (inside terminal field – outside terminal field) according to brain region. Black dots mark the outliers beyond three times the distance from the upper quartile (upper edge of the box) to the median (middle line in each box). B Post hoc contrasts between sites. C Visualization of functional connectivity differences for corresponding injection site/ROI on an inflated surface of the NMT template.

Dice coefficients were not different between cynomolgus and rhesus macaques (Wilcoxon rank sum test: p > 0.1), but functional connectivity inside vs outside the terminal field was higher for rhesus macaques than cynomolgus (p = 0.03). Furthermore, although the literature suggests a strong relationship between cortico-basal ganglia loops and motor control, cases from prefrontal regions did not have significantly reduced differences in functional connectivity between the areas inside vs outside of the terminal field than those from motor/premotor regions (F(1, 29) = -1.62, p > 0.1), nor did they have different Dice coefficients (F(1, 29) = 1.1, p > 0.2) (Supplementary Figure 1).

Finally, we asked about how functional and anatomical connectivity were distributed across the caudate, putamen, and nucleus accumbens (Fig. 6). Average functional connectivity in each nucleus was significantly correlated with terminal field size within each nucleus for frontal (r = .54, p < 0.0001) and somatosensory (r = 0.894, p < 0.0001) cases, but not extrastriate (r = 0.10, p = .64), temporal (r = 0.06, p = .67), insula (r = 0.24, p = 0.23), or parietal (r = 0.18, p = 0.29) cases.

Discussion

The topography of cortico-striatal anatomical connectivity has been well-defined in nonhuman animal models, including in macaques, which have strong cerebral cortical homologies with humans. In parallel, cortico-striatal functional connectivity is routinely evaluated in humans, and relationships have been found between these measures and disease, cognition, and development, amongst other metrics. Here, we sought to formally evaluate the relationship between anatomical and functional cortico-striatal connectivity in macaques, a species in which tract-tracing is possible. We found uneven levels of correspondence across different parts of the cerebral cortex. In particular, overlap between functional and anatomical connectivity was highest in the frontal, somatosensory, and insular cortices. It was lowest in the extrastriate and parietal cortices, with the temporal cortex occupying a middle level of overlap. The difference in functional connectivity inside vs outside the anatomical terminal field was likewise higher for frontal and somatosensory (but not insular or temporal) cortices, as was the match of connectivity distribution across striatal nuclei.

In general, mean Dice coefficients were not high ( < 0.5). However, we think it is unlikely that this represents the ceiling for overlap between functional and anatomical connectivity. Registration issues, species differences (the template was drawn exclusively from rhesus macaques, whereas anatomical and functional datasets were drawn from mixed macaque species), the fact that anatomy and fMRI datasets were from different cohorts, the relatively arbitrary cutoff for determining functional connectivity, the anesthesia used (isoflurane can impact resting-state fMRI), and incomplete anatomical data (particularly in the anterior-posterior dimension) certainly limit the Dice coefficient values. That is why we have focused on comparisons across regions, as well as thorough qualitative examinations of the data. (We have included Dice coefficients from an awake resting-state functional connectivity dataset (n = 2) in Supplementary Figure 2 to broadly confirm our results.)

There are several potential reasons to explain cortical region-specific results. Although we have long known that (nearly) the entire cerebral cortex projects to the striatum [66], traditionally we think of the frontal cortex as providing the strongest input [67]. Thus, one possibility is that the results shown here are the result of much stronger anatomical input to the striatum from some brain regions versus others. Determining the quantitative strength of the frontal cortex’s input to the striatum, relative to other cortical regions, is not straightforward. Answering this question is made challenging by the topographic nature of the striatum; that is, any given striatal injection site involves many cortical afferents, but it may not be in the zone of densest projection for some of them. Still, there is some quantitative evidence. Guo et al. [68] separately evaluated inputs to D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons and cholinergic interneurons to the dorsal striatum in mice. Indeed, the strongest inputs were from frontal regions (cingulate and motor cortices). However, projections from primary somatosensory cortex and visual cortices were only slightly lower. Following injections in the head of the caudate and the putamen in nonhuman primates, Weiss et al. [69] noted high levels of retrograde cell labeling in the frontal lobe relative to other cortical areas, with the exception of the insula, which they also noted as having high labeling. Similarly, McHale et al. [70] found in monkeys that projections to the ventral striatum from the insula, particularly the anterior insula, rival those from the prefrontal cortex in their strength. In addition, even older studies using degenerative techniques noted that projections from the frontal and somatosensory cortices were wider spread than those from visual cortex, although this is not the same as being denser [66]. Thus, while this question remains incompletely answered, it does seem plausible that the density of the cortico-striatal anatomical connection may account for observed matches and mismatches.

Another possibility is that cortico-basal ganglia loops may not complete (return to where they began) equally in all areas. The final link in the loops, the projection from the thalamus to the cortex, is surprisingly obscure. That is, we know a great deal about the thalamocortical projection in general; however, which thalamic neurons receive inputs from the globus pallidus internus and substantia nigra pars reticulata, and are thus capable of closing the cortico-basal ganglia loop, is unclear. This is an especially challenging problem to solve, because it requires careful, multisynaptic tract-tracing. Older views, focused on movement, were that the only portion of the loop that completely closed was the motor portion. In other words, it was thought that the basal ganglia directed its output only to the motor and premotor cortices [71]. Taking advantage of the transneuronal properties of the herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) [72], Strick and colleagues were able to identify some output channels in nonhuman primates. Injections into the primary motor cortex, the supplementary motor area, frontal eye fields, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the ventral premotor area all resulted in (retrograde, transsynaptic) labeling in the GPi/SNr, demonstrating that these cortical areas are the targets of basal ganglia-thalamic output [73,74,75]. Additional studies showed basal ganglia outputs to the inferotemporal cortex [76]. Beyond this limited set of regions, at this point, which cortical regions do and do not receive basal ganglia output are unclear.

Finally, there are different types of striatally-projecting cortical neurons. These neurons can be found in both layers III and V, and they can be intra-telencephalic (potentially projecting elsewhere in the telencephalon) or pyramidal tract (projecting outside of the telencephalon) [77,78,79]. Although the current study precludes evaluating cases according to proportions of these cell types, more recent, advanced methods for single axon reconstruction in the macaque offer just such a possibility in the future [80,81,82].

Matches (and mismatches) between anatomical and functional connectivity have been directly compared in the past. In one study of cortico-cortical connectivity, anatomical and functional connectivities were correlated at r = 0.3465, but correspondence was greatest for the strongest connections [33]. Another study of cortico-cortical connectivity, this one in marmosets, found a large range of correlation coefficients (0.2-0.8), depending on region [31]. Other, qualitative comparisons of functional vs anatomical cortico-striatal connectivity also find good correspondence in the frontal and somatosensory cortices, consistent with our results [23, 30]. Furthermore, Gordon and colleagues [83] used precision functional mapping (with a total of five hours of resting-state functional MRI data collected across 10 sessions) to identify cortico-striatal networks in the human brain. Importantly, they found that the frontal cortex was responsible for the majority of strong cortico-striatal functional connections.

Conclusion

In a direct, within-species examination of the overlap between functional and anatomical cortico-striatal connectivity, the frontal and somatosensory cortices stood out as having the strongest correspondence across multiple measures. Given that qualitative examinations of the extrastriate visual and associative parietal maps in particular showed very little overlap, it seems reasonable to conclude that cortico-striatal functional connectivity from these areas may not be driven by direct anatomical connectivity. Instead, extrastriate and associative parietal functional cortico-striatal connectivity may be determined, at least in part, by their cortico-cortical interactions with frontal and somatosensory cortices. Additional work will be needed to verify, at a network level, whether this is the case.

Data availability

Data are available at https://github.com/srheilbronner/corticostriatal.

References

Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–81.

Balleine BW, Delgado MR, Hikosaka O. The role of the dorsal striatum in reward and decision-making. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8161–5.

Graybiel AM, Grafton ST. The striatum: where skills and habits meet. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7:a021691.

Haber SN. Corticostriatal circuitry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18:7–21.

Berendse HW, Galisde Graaf Y, Groenewegen HJ. Topographical organization and relationship with ventral striatal compartments of prefrontal corticostriatal projections in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1992;316:314–47.

Ferry AT, Ongur D, An X, Price JL. Prefrontal cortical projections to the striatum in macaque monkeys: evidence for an organization related to prefrontal networks. Journal Comp Neurol. 2000;425:447–70.

Haber SN, Kim KS, Mailly P, Calzavara R. Reward-related cortical inputs define a large striatal region in primates that interface with associative cortical connections, providing a substrate for incentive-based learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8368–76.

Hintiryan H, Foster NN, Bowman I, Bay M, Song MY, Gou L, et al. The mouse cortico-striatal projectome. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1100–14.

Mailly P, Aliane V, Groenewegen HJ, Haber SN, Deniau JM. The rat prefrontostriatal system analyzed in 3D: evidence for multiple interacting functional units. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5718–27.

Dogan I, Eickhoff CR, Fox PT, Laird AR, Schulz JB, Eickhoff SB, et al. Functional connectivity modeling of consistent cortico-striatal degeneration in Huntington’s disease. NeuroImage: Clin. 2015;7:640–52.

Fettes P, Schulze L, Downar J. Cortico-striatal-thalamic loop circuits of the orbitofrontal cortex: promising therapeutic targets in psychiatric illness. Front Syst Neurosci. 2017;11:25.

Peters SK, Dunlop K, Downar J. Cortico-striatal-thalamic loop circuits of the salience network: a central pathway in psychiatric disease and treatment. Front Syst Neurosci. 2016;10:104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2016.00104.

Helmich RC, Derikx LC, Bakker M, Scheeringa R, Bloem BR, Toni I. Spatial remapping of cortico-striatal connectivity in Parkinson’s Disease. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:1175–86.

Sha Z, Versace A, Edmiston EK, Fournier J, Graur S, Greenberg T, et al. Functional disruption in prefrontal-striatal network in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res: Neuroimaging. 2020;300:111081.

Furman DJ, Hamilton JP, Gotlib IH. Frontostriatal functional connectivity in major depressive disorder. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord. 2011;1:1–11.

Haag L, Quetscher C, Dharmadhikari S, Dydak U, Schmidt-Wilcke T, Beste C. Interrelation of resting state functional connectivity, striatal GABA levels, and cognitive control processes. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4383–93.

Raghanti MA, Miller EN, Jones DN, Smith HN, Munger EL, Edler MK, et al. Hedonic eating, obesity, and addiction result from increased neuropeptide Y in the nucleus accumbens during human brain evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120:e2311118120.

Toni I. Changes of cortico-striatal effective connectivity during visuomotor learning. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:1040–7.

Harsay HA, Cohen MX, Oosterhof NN, Forstmann BU, Mars RB, Ridderinkhof KR. Functional connectivity of the striatum links motivation to action control in humans. Journal Neurosci. 2011;31:10701–11.

Horga G, Maia TV, Marsh R, Hao X, Xu D, Duan Y, et al. Changes in corticostriatal connectivity during reinforcement learning in humans. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:793–803.

Frank LE, Preston AR, Zeithamova D. Functional connectivity between memory and reward centers across task and rest track memory sensitivity to reward. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2019;19:503–22.

Yeo BT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–65.

Choi EY, Yeo BT, Buckner RL. The organization of the human striatum estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2012;108:2242–63.

Di Martino A, Scheres A, Margulies DS, Kelly AM, Uddin LQ, Shehzad Z, et al. Functional connectivity of human striatum: a resting state FMRI study. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:2735–47.

Calzavara R, Mailly P, Haber SN. Relationship between the corticostriatal terminals from areas 9 and 46, and those from area 8A, dorsal and rostral premotor cortex and area 24c: an anatomical substrate for cognition to action. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:2005–24.

Zald DH, McHugo M, Ray KL, Glahn DC, Eickhoff SB, Laird AR. Meta-analytic connectivity modeling reveals differential functional connectivity of the medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:232–48.

Flaherty AW, Graybiel AM. Two input systems for body representations in the primate striatal matrix: experimental evidence in the squirrel monkey. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1120–37.

Draganski B, Kherif F, Klöppel S, Cook PA, Alexander DC, Parker GJM, et al. Evidence for segregated and integrative connectivity patterns in the human basal ganglia. Journal Neurosci. 2008;28:7143–52.

Marquand AF, Haak KV, Beckmann CF. Functional corticostriatal connection topographies predict goal-directed behaviour in humans. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1:0146.

Peng X, Trambaiolli LR, Choi EY, Lehman JF, Linn G, Russ BE, et al. Cross-species striatal hubs: Linking anatomy to resting-state connectivity. Neuroimage. 2024;301:120866.

Hori Y, Schaeffer DJ, Gilbert KM, Hayrynen LK, Cléry JC, Gati JS, et al. Comparison of resting-state functional connectivity in marmosets with tracer-based cellular connectivity. Neuroimage. 2020;204:116241.

Shen K, Bezgin G, Hutchison RM, Gati JS, Menon RS, Everling S, et al. Information processing architecture of functionally defined clusters in the macaque cortex. J Neurosci. 2012;32:17465–76.

Miranda-Dominguez O, Mills BD, Grayson D, Woodall A, Grant KA, Kroenke CD, et al. Bridging the gap between the human and macaque connectome: a quantitative comparison of global interspecies structure-function relationships and network topology. J Neurosci. 2014;34:5552–63.

Manea AM, Zilverstand A, Ugurbil K, Heilbronner SR, Zimmermann J. Intrinsic timescales as an organizational principle of neural processing across the whole rhesus macaque brain. eLife. 2022;11:e75540.

Yacoub E, Grier MD, Auerbach EJ, Lagore RL, Harel N, Adriany G, et al. Ultra-high field (10.5 T) resting state fMRI in the macaque. Neuroimage. 2020;223:117349.

Lagore RL, Moeller S, Zimmermann J, DelaBarre L, Radder J, Grant A, et al. An 8-dipole transceive and 24-loop receive array for non-human primate head imaging at 10.5 T. NMR Biomed. 2021;34:1–11.

Moeller S, Yacoub E, Olman CA, Auerbach E, Strupp J, Harel N, et al. Multiband multislice GE-EPI at 7 tesla, with 16-fold acceleration using partial parallel imaging with application to high spatial and temporal whole-brain fMRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:1144–53.

Setsompop K, Cohen-Adad J, Gagoski BA, Raij T, Yendiki A, Keil B, et al. Improving diffusion MRI using simultaneous multi-slice echo planar imaging. Neuroimage. 2012;63:569–80.

Ugurbil K, Xu J, Auerbach EJ, Moeller S, Vu AT, Duarte-Carvajalino JM, et al. Pushing spatial and temporal resolution for functional and diffusion MRI in the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage. 2013;80:80–104.

Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782–90.

Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2033–44.

Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Stauffer M, Song G, Wu B, Gee JC. The Insight ToolKit image registration framework. Front Neuroinform. 2014;8:1–13.

Cox RW. AFNI: Software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–73.

Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Nieto-Castanon A. Conn: A functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect. 2012;2:125–41.

Seidlitz J, Sponheim C, Glen D, Ye FQ, Saleem KS, Leopold DA, et al. A population MRI brain template and analysis tools for the macaque. Neuroimage. 2018;170:121–31.

Hallquist MN, Hwang K, Luna B. The nuisance of nuisance regression: Spectral misspecification in a common approach to resting-state fMRI preprocessing reintroduces noise and obscures functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2013;82:208–25.

Seidlitz J, Sponheim C, Glen D, Ye FQ, Saleem KS, Leopold DA. A population MRI brain template and analysis tools for the macaque. NeuroImage. 2017;170:121–31.

Baizer JS, Desimone R, Ungerleider LG. Comparison of subcortical connections of inferior temporal and posterior parietal cortex in monkeys. Vis Neurosci. 1993;10:59–72.

Chikama M, McFarland NR, Amaral DG, Haber SN. Insular cortical projections to functional regions of the striatum correlate with cortical cytoarchitectonic organization in the primate. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9686–705.

Choi EY, Ding S-L, Haber SN. Combinatorial inputs to the ventral striatum from the temporal cortex, frontal cortex, and amygdala: implications for segmenting the striatum. eNeuro. 2017;4:ENEURO.0392-17.2017.

Choi EY, Tanimura Y, Vage PR, Yates EH, Haber SN. Convergence of prefrontal and parietal anatomical projections in a connectional hub in the striatum. Neuroimage. 2017;146:821–32.

Fudge JL, Breitbart MA, Danish M, Pannoni V. Insular and gustatory inputs to the caudal ventral striatum in primates. J Comp Neurol. 2005;490:101–18.

Jezzini A, Rozzi S, Borra E, Gallese V, Caruana F, Gerbella M. A shared neural network for emotional expression and perception: an anatomical study in the macaque monkey. Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:243. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00243.

Jones EG, Coulter JD, Burton H, Porter R. Cells of origin and terminal distribution of corticostriatal fibers arising in the sensory-motor cortex of monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1977;173:53–80.

Kunzle H. Projections from the primary somatosensory cortex to basal ganglia and thalamus in the monkey. Exp Brain Res. 1977;30:481–92.

Parvizi J, Van Hoesen GW, Buckwalter J, Damasio A. Neural connections of the posteromedial cortex in the macaque. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1563–8.

Schmahmann J, Pandya D Fiber Pathways of the Brain. Oxford University Press, Inc.: New York, 2006.

Weber JT, Yin TC. Subcortical projections of the inferior parietal cortex (area 7) in the stump-tailed monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1984;224:206–30.

Yeterian EH, Pandya DN. Corticostriatal connections of extrastriate visual areas in rhesus monkeys. Journal Comp Neurol. 1995;352:436–57.

Yeterian EH, Pandya DN. Corticostriatal connections of the superior temporal region in rhesus monkeys. Journal Comp Neurol. 1998;399:384–402.

Heilbronner SR, Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Quirk GJ, Groenewegen HJ, Haber SN. Circuit-based corticostriatal homologies between rat and primate. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:509–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.012.

Monko ME, Heilbronner SR. Retrosplenial cortical connectivity with frontal basal ganglia networks. J Cogn Neurosci. 2021;33:1096–105.

Hartig R, Glen D, Jung B, Logothetis NK, Paxinos G, Garza-Villarreal EA, et al. The subcortical atlas of the rhesus macaque (SARM) for neuroimaging. Neuroimage. 2021;235:117996.

Averbeck BB, Lehman J, Jacobson M, Haber SN. Estimates of projection overlap and zones of convergence within frontal-striatal circuits. J Neurosci. 2014;34:9497–505.

Wobbrock JO, Findlater L, Gergle D, Higgins JJ The aligned rank transform for nonparametric factorial analyses using only anova procedures. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM: Vancouver BC Canada, 2011, pp 143-6.

Kemp JM, Powell TP. The cortico-striate projection in the monkey. Brain. 1970;93:525–46.

Haber SN. The primate basal ganglia: parallel and integrative networks. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;26:317–30.

Guo Q, Wang D, He X, Feng Q, Lin R, Xu F, et al. Whole-brain mapping of inputs to projection neurons and cholinergic interneurons in the dorsal striatum. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0123381.

Weiss AR, Liguore WA, Domire JS, Button D, McBride JL. Intra-striatal AAV2.retro administration leads to extensive retrograde transport in the rhesus macaque brain: implications for disease modeling and therapeutic development. Sci Rep. 2020;10:6970. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63559-7.

McHale AC, Cho YT, Fudge JL. Cortical granularity shapes the organization of afferent paths to the amygdala and its striatal targets in nonhuman primate. J Neurosci. 2022;42:1436–53.

Kemp JM, Powell TP. The connexions of the striatum and globus pallidus: synthesis and speculation. Philosophical Trans R Soc Lond - Ser B: Biol Sci. 1971;262:441–57.

Strick PL, Card JP Transneuronal mapping of neural circuits with alpha herpesviruses. Experimental neuroanatomy: a practical approach (Bolam JP, ed) 1992; : 81–101.

Hoover JE, Strick PL. Multiple output channels in the basal ganglia. Science. 1993;259:819–21.

Lynch JC, Hoover JE, Strick PL. Input to the primate frontal eye field from the substantia nigra, superior colliculus, and dentate nucleus demonstrated by transneuronal transport. Exp Brain Res. 1994;100:181–6.

Middleton FA, Strick PL. Anatomical evidence for cerebellar and basal ganglia involvement in higher cognitive function. Science. 1994;266:458–61.

Middleton FA, Strick PL. The temporal lobe is a target of output from the basal ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8683–7.

Levesque M, Parent A. Axonal arborization of corticostriatal and corticothalamic fibers arising from prelimbic cortex in the rat. Cereb Cortex. 1998;8:602–13.

Levesque M, Parent A. The striatofugal fiber system in primates: a reevaluation of its organization based on single-axon tracing studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11888–93.

Wilson CJ. Postsynaptic potentials evoked in spiny neostriatal projection neurons by stimulation of ipsilateral and contralateral neocortex. Brain Res. 1986;367:201–13.

Gou L, Wang Y, Gao L, Liu S, Wang M, Chai Q, et al. Single-neuron projectomes of macaque prefrontal cortex reveal refined axon targeting and arborization. Cell. 2025;188:3806–22.e24.

Li S, Shen Y, Chen Y, Hong Z, Zhang L, Ding L, et al. Single-neuron reconstruction of the macaque primary motor cortex reveals the diversity of neuronal morphology. Neurosci Bull. 2025;41:525–30.

Xu F, Shen Y, Ding L, Yang C-Y, Tan H, Wang H, et al. High-throughput mapping of a whole rhesus monkey brain at micrometer resolution. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39:1521–8.

Gordon EM, Laumann TO, Marek S, Newbold DJ, Hampton JM, Seider NA, et al. Individualized functional subnetworks connect human striatum and frontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2022;32:2868–84.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Tanya Casta, Maya Wang, and Adriana Cushnie for assistance with data collection.

Funding

We acknowledge funding from R01MH118257, P30DA04872, R01EB031765, P41EB027061, and the Robert and Janice McNair Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MEM and SRH designed the study. MEM, AMGM, FAO, DH, J Zhou, J Zimmermann, and SRH collected data. WT, MEM, ZL, AMG, JZ, and SRH analyzed data. J Zimmermann and SRH contributed project funding, administration, and supervision. WT and SRH wrote the first manuscript draft. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Minnesota (PHS Approved Animal Welfare Assurance D16-00288).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, W., Monko, M.E., Liu, Z. et al. Functional vs anatomical cortico-striatal connectivity in the macaque brain. Transl Psychiatry 16, 13 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03757-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03757-x