Abstract

Approximately 23% of the men and women who participated in rescue and recovery efforts at the 9/11 World Trade Center (WTC) site experience persistent, clinically significant post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Recent structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies demonstrate significant neural differences between WTC responders with and without PTSD. Here, we used brain age, a novel MRI-based data-driven biomarker optimized to detect accelerated structural aging and examined the impact of PTSD on this process. Using BrainAgeNeX, a novel convolutional neural network that bypasses brain parcellation and has been trained and validated on over 11,000 T1-weighted MRI scans, we predicted brain age in WTC responders with PTSD (WTC-PTSD, n = 47) and age/sex matched responders without PTSD (non-PTSD, n = 52). Brain Age Difference (BAD) was then calculated for each WTC responder by subtracting chronological age from brain age. We found that BAD was significantly older in WTC-PTSD compared to non-PTSD responders (BADno_PTSD = −0.43 y; BADWTC_PTSD = 3.07 y; p < 0.001). Further, we found that WTC exposure duration (months working on site) moderates the association between PTSD and BAD (p = 0.005). Our results suggest that brain age is a relevant marker of structural damage in WTC responders with and without PTSD. PTSD may be a risk factor for accelerated aging in trauma-exposed populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals involved in rescue and recovery efforts at the World Trade Center (WTC) site following the 9/11 attacks exhibit a notably higher prevalence of chronic, clinically significant post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [1, 2], exceeding rates observed in the general U.S. population [3]. PTSD is a neuropsychiatric condition triggered by the experience of traumatic events, characterized by hypervigilance and hyperarousal, intrusive and recurrent flashbacks or dreams, and psychological and physiological distress in response to trauma-resembling cues [4]. Among WTC responders and, more generally, in the PTSD patient population, PTSD has been linked to several epigenomic, immune, and inflammatory biomarkers indicative of accelerated cellular aging, compared to chronological aging [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Individuals with PTSD have been identified as being at increased risk of age-related medical conditions, such as premature cognitive decline [16, 17]. Individuals diagnosed with PTSD early in life ( < 40 years old) are twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s later in life [16, 17] with neurodegenerative pathological signatures including hippocampal volume loss [18,19,20,21], cortical thinning [22,23,24], changes in white matter connectivity, and amyloidosis [25]. These brain changes indicating pathological aging culminate to increased morbidity and mortality [26], posing a significant health threat to this already vulnerable population. These brain changes are especially notable in the population of WTC responders, who face an exacerbated prevalence of premature cognitive impairment and its neuropathological underpinnings in mid-life, decades earlier than when age-expected neurocognitive decline typically is observed [27,28,29].

Recent neuroimaging studies of WTC responders, including work from our group, leverage a diverse array of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) modalities to examine structural brain changes [30,31,32] and functional neural mechanisms [32,33,34,35,36,37], such as reduced cortical complexity [32], observed in responders with PTSD (WTC-PTSD) and those without PTSD (non-PTSD). Several studies have shown that responders with greater exposure to the disaster site and more severe PTSD symptoms show increased vulnerability to brain changes, including cortical atrophy and neuropathy [27, 37,38,39]. These findings underscore the neurological burden experienced by WTC responders with PTSD. Cortical atrophy and peripheral neuropathy were previously observed in this population and are consistent with patterns of accelerated brain aging, which have been increasingly recognized among individuals with chronic stress-related disorders such as PTSD [29, 40]. Yet, the identification of a whole-brain aging biomarker applicable to the population of WTC responders has yet to be established.

The pressing need to disentangle PTSD and its impact on the trajectory of healthy brain aging necessitates the identification of prodromal biomarkers sensitive to accelerated aging and related neurodegeneration. This prodromal biomarker will help to inform diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment intervention. “Brain age” is an estimate of the biological age of the brain based on MRI scans. MRI-based brain age has proven to be a valuable marker for identifying accelerated aging, particularly by detecting subtle brain atrophy and early neurodegenerative changes that may not be found in a standard clinical assessment [41]. Here, we apply a state-of-the-art whole-brain MRI-based brain age estimation method sensitive to accelerated brain aging across the entire human lifespan. Among WTC responders with and without PTSD, we calculate and compare responders’ “brain age” to chronological age to derive “brain age difference (BAD) [42, 43], a prodromal biomarker of an individual’s brain aging with reference to normative brain aging curvatures. Using BAD, we compare neurological aging signatures between responders with and without PTSD, identify brain regions associated with BAD, and gain insight into the neural mechanisms driving accelerated brain aging in PTSD. Finally, we examine how the association between BAD and PTSD is moderated by the duration of responders’ WTC-related exposure. This study expands our knowledge of the neurological basis linking PTSD and brain aging, highlighting the impact of exposures during 9/11 rescue and recovery efforts on the human brain in WTC-responders.

Methods and materials

Participants

In 2002, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), through the World Trade Center (WTC) Health Program, began monitoring over 50,000 WTC responders using a comprehensive health surveillance protocol at several clinical centers throughout the New York City metropolitan area [44,45,46]. The Stony Brook University (SBU) site monitors law enforcement and non-law enforcement responders (e.g., construction workers, utility personnel, and volunteers) who primarily reside on Long Island, New York [45, 47]. These responders are evaluated for a range of health conditions, including PTSD and cognitive status. A subset of the individuals at the SBU site participated in a voluntary substudy involving structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [27, 37, 45, 47]. Briefly, all participants had been involved in rescue, recovery, cleanup, or related operations following the 9/11 attacks [45, 46]. Eligible participants were between the ages of 44 and 65, fluent in English, and met MRI safety criteria (e.g., no metal implants, no shrapnel, no claustrophobia, no history of traumatic brain injury, and BMI ≤ 40).

Diagnostic assessment of PTSD was determined from the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID-IV) [48], a semi-structured interview administered by trained clinical interviewers. The PTSD module used WTC exposures as the index trauma. Eligibility criteria for PTSD status was presence (PTSD)/absence (non-PTSD) of current PTSD diagnosis. Symptom subdomains were measured using subscales calculated based on reported symptom severity in the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (SCID-IV) for the following symptom domains: re-experiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal, and negative thoughts (scores ranging from [10–30], [14–42], [10–30], [8–24], respectively). Major depressive disorder (MDD) was also assessed using the SCID-IV, the presence or absence of current (i.e., active in the past month) MDD was determined. Current MDD is a common comorbidity of PTSD and was not an exclusion criterion.

Upon enrollment, case (WTC-PTSD) and control (non-PTSD) groups were matched based on age, sex, race/ethnicity, occupation (i.e., law enforcement), cognitive status, and education at the time of 9/11. Supplemental details on participants’ ethnicity, occupation, time of arrival on 9/11/2001, exposure to human remains, dust cloud exposure, witnessing the suffering of a family member, friend, or colleague, and whether they experienced personal loss can be found in supplementary material (Table S1).

Ethics

Study procedures that follow the Declaration of Helsinki, were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both Stony Brook University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. All participants signed informed consents upon explanation of study procedures prior to enrollment.

WTC exposure duration

Upon enrollment into the WTC General Responders Cohort [45], all responders completed a questionnaire about their experience during rescue and recovery efforts. WTC exposure was calculated from self-reported responses to items regarding the time spent (expressed in months and collected at enrollment in the parent study) working on the WTC sites [28, 49]. This exposure variable was not available for 10 participants in our study. There were no significant differences in any demographic characteristics or PTSD status between participants with missing exposure data (n = 10) compared to those with complete exposure data (n = 89; Table 1). Therefore, we imputed missing exposure data using the chained equations method available through the mice package in R. This approach estimates missing values by leveraging the relationships among variables in the dataset and accounts for the uncertainty introduced by the imputation process.

MRI data acquisition and preprocessing

MRI data acquisition was performed on a 3-Tesla SIEMENS mMR Biograph scanner using a 20-channel head and neck coil. For each WTC responder, a high-resolution 3D T1-weighted structural brain scan was acquired using a MPRAGE sequence (TR=1900ms, TE = 2.49 ms, TI = 900 ms, flip angle=9, acquisition matrix=256 × 256 and 224 slices with final voxel size=0.89 × 0.89 × 0.89 mm). All T1w images underwent skull-stripping using SynthStrip [50], N4 bias field correction with default parameters, and linear registration with 6 degrees of freedom to the MNI152 1 mm isotropic space with ANTs [51]. This minimal preprocessing ensures that all anatomical images are in the same space, enabling consistent analysis across subjects.

Brain age prediction: BrainAgeNeXt

To predict brain age, we applied the BrainAgeNeXt model [52], a novel convolutional neural network (CNN) designed for accurate brain age estimation from T1-weighted MRI scans. BrainAgeNeXt is based on the MedNeXt architecture, a transformer-inspired CNN developed specifically for 3D medical images [53]. The original MedNeXt segmentation network has been adapted by using only the encoder path for the brain age regression task. The model automatically extracts relevant features from the entire 3D volume of T1-weighted MRI scans, offering a significant advantage over older machine learning methods that rely on pre-extracted brain volumetric features [54]. BrainAgeNeXt [52] was trained on a large dataset of 11,574 1.5 T and 3 T MRI scans from healthy individuals, aged 5 to 95 years, who were imaged at 75 sites. The method consists of five individual models, all trained in the same way with randomly initialized weights, and the final output is obtained by combining their predictions using a mean ensemble approach. On a separate testing set of 1,523 MRI scans, BrainAgeNeXt achieved a mean age error (MAE) of 2.78 ± 3.64 years, outperforming state-of-the-art methods [55, 56]. MAE is defined as the average absolute difference between the predicted brain age and the true chronological age. This metric is commonly used to evaluate brain age models because it directly reflects the accuracy of age prediction in healthy individuals, where the chronological age serves as the ground truth. In our study, each subject’s T1-weighted scan was processed through BrainAgeNeXt to obtain the predicted brain age. We then calculated the difference between brain age and chronological age to determine the Brain Age Difference (BAD) as it serves as a quantitative marker of brain aging. To demonstrate the robustness of this new model, we applied two additional algorithms to predict brain age, brainageR [55] and pyment [56] (Table 2). Then, to better understand BrainAgeNeXt predictions, we investigated monotonic correlations between brain volumes as obtained using SynthSeg [57] based on FreeSurfer [56], a segmentation approach based on CNN trained with synthetic data, and BAD were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation in all 99 WTC-responders and then, stratified by responders with PTSD (WTC-PTSD) and without PTSD (non-PTSD; Fig. 2).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in the R statistical software package, version 4.4.3. To examine differences in clinical and demographic characteristic across groups (WTC-PTSD and non-PTSD), pairwise Student t-test with Welch’s correction for continuous variables and \({\chi }_{2}\) tests for categorical variables were used. To assess model performance, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficient (R) and the explained variance of the model (VE) between chronological age and predicted brain age. BAD (predicted brain age - chronological age) was calculated for each subject, using BrainAgeNeXt, and was used as the primary outcome measure. To quantify differences in predicted age and BAD between WTC responders with and without PTSD, pairwise Student t-tests were used. To quantify differences in brain volumes, we combined brain volumes from the left and right hemispheres, and each volume was normalized by the total intracranial volume. Statistical significance was determined using a p-value threshold of 0.05. Finally, to test our hypothesis that WTC exposure duration (months on site) moderated the association between PTSD and BAD, general linear model (GLM) regressions were computed using current PTSD diagnosis and cumulative WTC exposure duration expressed in months as predictors and BAD as the outcome.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 1 reports the clinical and demographic characteristics for the 99 WTC responders included in this study stratified by responders with PTSD (WTC-PTSD) and without PTSD (non-PTSD). Responders were in their mid-fifties at the time of the imaging data acquisition (55.8 ± 5.2 years) and the majority were male (78%). By design, the groups were matched, resulting in no significant differences in age at the time of neuroimaging, sex, race/ethnicity, or educational attainment. Current MDD and PTSD symptoms scales (DSM-IV SCID trauma screen) significantly differ between groups: WTC-PTSD had a significantly higher prevalence of MDD compared to non-PTSD (40% vs 0%) and had higher scores across the PTSD symptom sub scales (Table 1). No significant difference in WTC exposure duration was found between WTC responders with/without PTSD (average months on site for WTC-PTSD = 2.88 and non-PTSD = 2.58, p = 0.771).

Prediction of brain age in WTC responders

Brain age in WTC responders was estimated using three algorithms: brainageR, pyment, and BrainAgeNeXt (Table 2). Across all three methods, we observed a statistically significant difference between PTSD– and PTSD+ participants, with the PTSD+ group showing, on average, higher brain age estimates relative to their chronological age. Among the three algorithms, BrainAgeNeXt has previously demonstrated superior performance in terms of mean age error when evaluated on an independent test dataset of 1,523 MRI scans from healthy volunteers [52]. This evidence supports our decision to adopt BrainAgeNeXt as the primary brain age prediction approach for the subsequent analyses of the present study.

Predicted brain age from BrainAgeNeXt and chronological age were significantly and positively correlated (R = 0.77 and VE = 59.31%), while there is no significant correlation between BAD and chronological age (R = 0.11, p = 0.25). By design, sample subgroups were matched on chronological age at the time of scan thus there were no differences in chronological age between WTC-PTSD and non-PTSD (p = 0.33; Table 3 and Fig. 1, panel A). No significant difference was observed in predicted brain age between WTC-PTSD and non-PTSD (p = 0.099; Table 3 and Fig. 1, panel B). BAD differed significantly between WTC-PTSD and non-PTSD responders where WTC-PTSD shown a higher mean BAD of 3.1 years [minimum of −9.4 and maximum of 11.7 years] compared to non-PTSD responders, who had a mean BAD of −0.4 years, p < 0.001 (Table 3 and Fig. 1, panel C).

Density plots showing the distribution of chronological age (Panel A), predicted brain age (Panel B) and Brain Age Difference (BAD; Panel C) stratified by WTC-PTSD (orange line) and non-PTSD (blue line). Only BAD differed significantly between WTC-PTSD and non-PTSD groups. Significance level: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Brain volumes and BAD

Across All WTC-responders (Fig. 2, panel A), BAD was most strongly correlated with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and ventricular volumes: fourth ventricle (r = 0.424, p < 0.001), third ventricle (r = 0.621, p < 0.001), lateral ventricle (r = 0.461, p < 0.001), inferior lateral ventricle (r = 0.452, p < 0.001) and cerebrospinal fluid (r = 0.424, p < 0.001). For non-PTSD responders (Fig. 2, panel B), BAD was significantly correlated with the fourth ventricle (r = 0.615, p < 0.001), third ventricle (r = 0.611, p < 0.001), inferior lateral ventricle (r = 0.519, p < 0.001) and cerebrospinal fluid (r = 0.51, p < 0.001). For WTC-PTSD responders (Fig. 2, panel C), BAD correlated significantly with the third ventricle (r = 0.591, p < 0.001) and lateral ventricle (r = 0.581, p < 0.001). Correlations between brain volumes and predicted brain age are reported in supplementary materials (Figure S1). Interestingly, the thalamus emerged as the only non-ventricular brain region negatively associated with increased predicted brain age in WTC-PTSD responders but not in those without PTSD (Figure S1). Finally, CSF and ventricular volumes that were significantly correlated with BAD and/or predicted brain age metrics were not significantly different between responders with and without PTSD (Table S2).

Correlations between brain volumes (normalized for intracranial brain volume) and BAD for all 99 WTC responders (Panel A), non-PTSD (Panel B) and WTC-PTSD (Panel C). Brain parcellation was performed with SynthSeg (FreeSurfer) [57]. Significance level: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Impact of WTC exposure on BAD

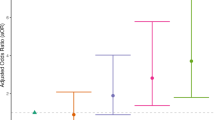

Results from generalized linear modeling suggest that WTC exposure duration (months on site) moderates the association between PTSD and BAD (p-value for interaction = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.01, 1.12]; Fig. 3, Table 4). In WTC-PTSD responders, prolonged WTC exposure is associated with increased BAD. Models that used chronological and predicted age as outcomes are reported in supplementary materials (Figure S2). Supplementary materials report results of prolonged WTC exposure and BAD adjusting for chronological age and MDD (Table S3).

This graph plots the relationship (interaction) between WTC exposure duration in months (x-axis) and brain age difference (BAD) (y-axis) stratified by WTC-PTSD (orange dots) and non-PTSD (blue dots). WTC exposure duration (months on site) moderates the association between PTSD status and BAD (p-value for interaction = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.01, 1.12]).

Discussion

MRI-based brain age models are key to understanding healthy aging trajectories, identifying deviations from these patterns, and identifying prodromal biomarkers that may indicate accelerated brain aging. These models provide valuable insights into the brain’s structural changes, helping to link early signs of neurodegenerative diseases with long-term clinical outcomes. In this study, we investigated the relationship between traumatic exposures, PTSD, and brain age among WTC responders. Using a novel convolutional neural network (BrainAgeNeXt), we determined predicted-brain age, estimating the BAD, an imaging biomarker derived from anatomical MRI that captures structural brain variations with high precision for each WTC responder. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that depend on pre-extracted volumetric features, BrainAgeNeXt automatically extracts relevant features from the full 3D volume of T1-weighted MRI scans, offering a significant methodological advantage [54]. We found a significant increase in BAD among responders with PTSD compared to those without (p < 0.001), providing evidence of an association between PTSD and premature brain aging. To further establish the robustness of this finding, we also tested two additional brain age models, and the pattern of accelerated aging among responders with PTSD was observed across methods, indicating that the finding is agnostic to the specifics of any single algorithm. Additionally, the duration of WTC exposure (months on site working in rescue and recovery efforts) moderated the association between PTSD and BAD (p = 0.05). These findings demonstrate a link between PTSD and brain aging, highlighting CSF and ventricular volumes that may be associated with greater BAD among responders with PTSD. This suggests that PTSD is a substantial risk factor for accelerated brain aging – a process moderated by the degree of exposure to the rescue and recovery site. Our findings also provide support for the use of “brain age” and “BAD” as promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for accelerated aging in the broader vulnerable population of aging individuals diagnosed with PTSD.

Brain age significantly differs between WTC responders with and without PTSD, with those experiencing WTC-related PTSD showing accelerated brain aging, as reflected by higher Predicted Age Difference (BAD) estimates - the gap between brain predicted and chronological age (Table 3, Fig. 1). Previous studies have already linked PTSD among WTC responders to anatomical [32, 35] and functional neural changes [33], as well as a range of aging-related conditions manifesting clinically as memory loss [28], increased risk of cognitive impairment [58,59,60] and physical functional limitations [61]. Additionally, studies within the broader WTC cohort have shown that markers of epigenetic and transcriptomic aging, such as gene expression [62] and DNA methylation [15], suggest that WTC responders with PTSD are aging at a significantly faster rate than those without PTSD [9]. These molecular findings, along with observed structural and functional brain changes, provide compelling evidence linking PTSD to accelerated aging in the WTC responder population. Taken together, these findings highlight the profound impact of PTSD on long-term brain health, underscoring that PTSD is not only a chronic psychological condition but also a significant contributor to accelerated biological aging [12, 63], with its underlying neural mechanisms playing a key role in this process. Future analyses investigating the relationship between brain age and measures of epigenetic and transcriptomic aging in this unique cohort are warranted to further elucidate these associations Table 4.

As our population ages, there is an increasing need to understand where and how the brain changes over time and the clinical implications of these changes [64]. A notable strength of our study was using a convolutional neural network to derive brain age [52]. One of the key advantages of BrainAgeNeXt is its ability to learn directly from 3D MRI data without relying on pre-extracted volumetric features. While this approach mitigates the issues associated with brain parcellation variability and facilitates the model’s applicability to real-world clinical settings, a limitation is understanding the neural drivers of prediction. To overcome this, we explored which brain area volumes were most correlated with BAD. Among WTC responders, we found that BAD was correlated with CSF and several ventricular volumes (Fig. 2). These findings align with well-established aging patterns, where increased CSF volume reflects brain atrophy, including cortical shrinkage and ventricular enlargement [65]. This volumetric increase in CSF is typical of normal aging, indicating brain atrophy [66, 67], but is often more pronounced in neurodegenerative conditions [68,69,70]. Finally, as interest grows in identifying methods to monitor increased risk of neurodegeneration conditions, our findings establish that brain age is a valuable and robust biomarker for detecting accelerated aging processes in PTSD. Our findings underscore the need for continued research in this area. Future studies should explore whether therapeutic interventions in WTC responders can slow the rate of accelerated aging, particularly among those with PTSD. Additionally, there is a critical need to investigate the relationship between the influence of trauma exposure and PTSD severity on accelerated brain aging. Understanding these connections could pave the way for targeted interventions to promote healthier brain aging in populations affected by PTSD.

We investigated the correlation between the predicted brain age and brain volumes. Interestingly, the thalamus emerged as the only non-ventricular brain region negatively associated with increased predicted age in WTC-PTSD responders but not in those without PTSD (Figure S1). None of these brain volumes showed statistically significant differences between responders with and without PTSD (Table S2). The thalamus plays a key role in sensory, emotional, and fear regulation, acting as a relay between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. In animal models, the thalamus showed vulnerability to the cumulative effects of both psychological and environmental stress [71]. Neuronal cell death was observed in brain areas, including the thalamus, among rats with combined exposure to stress and low doses of environmental neurotoxins [71]. Reduced thalamic volume has been observed in structural MRI studies of PTSD, consistent with our finding that smaller thalamic volumes are linked to greater predicted age in responders with PTSD [72, 73]. Among the WTC cohort, previous studies identified reduced white matter integrity in the thalamic radiation, a connection between the thalamus to the cerebral cortex [74]. Intriguingly, epidemiologic studies in this cohort and others have reported evidence of slowed cognitive and physical responses, which may be consistent with thalamic aging [59, 61]. Further studies are necessary to explore the specific role of the thalamus and other brain structures most vulnerable to this decline, which may become key targets for clinical therapies aimed at mitigating and slowing down the accelerated neurodegenerative processes.

Among the more than 35,000 responders enrolled in the ongoing WTC-HP, 23% of them continue to experience chronic WTC-related PTSD [1, 26, 75]. In this study of responders selected based on PTSD case status (WTC-PTSD vs WTC non-PTSD), the duration of WTC exposure (i.e., number of months spent at the WTC site in rescue and recovery efforts) did not differ between responders with PTSD and those without PTSD (Table 1). While all responders experienced some degree of traumatic exposure, not all responders developed PTSD. Among responders with PTSD, greater BAD is associated with prolonged WTC exposure during search and rescue efforts during and following 9/11 (Fig. 3), suggesting that prolonged exposure may exacerbate the already adverse effects of PTSD on brain aging in this vulnerable population. During these months on the pile, WTC responders experienced psychologically traumatic stressors and inhaled dust and smoke containing many pollutants (i.e., particulate matter, lead, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and dioxins). Circulating particulates and/or toxicants may have reached the brain through the olfactory system, disrupting blood-brain barrier function, and inducing neuroinflammation at the global-network [28, 49]. This unique combined exposure to traumatic stressors and environmental toxicants may play a role in the anatomical and functional changes observed in our population [76,77,78,79]. Although all participants were WTC responders, we lack detailed individual-level data on specific airborne toxin or pollutant exposure. As such, we used “time on the pile” as a proxy for exposure in this work; while informative, it does not provide the resolution necessary to assess differential exposure across individuals. However, our results are consistent with previous studies within the WTC cohort that found associations between longer-duration WTC exposure and greater structural changes such as reduced cortical volumetric and decreased cortical complexity [32, 35]. Synthesizing our results and prior literature, there may be a synergistic interaction between PTSD and prolonged exposure to psychological and environmental stressors at play, amplifying responders’ susceptibility to accelerated aging.

Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of using a whole-brain MRI-based “brain age” biomarker to identify and quantify deviations from healthy aging trajectories, assessing an increased risk of accelerated aging. “Brain age” is a well-validated measure in healthy individuals and has been extensively studied in populations with neurodegenerative diseases [80,81,82] and neuropsychiatric disorders [52, 83,84,85]. However, the application of “brain age” to PTSD is largely underexplored. While recent studies suggest a potential link between PTSD and accelerated brain aging as measured by BAD [55, 86], these findings have been inconsistent and suffer from methodological biases. One study found preliminary evidence that PTSD may be associated with accelerated brain aging [86], but it had several limitations including a younger participant sample and imbalanced group sizes. Another study reported that young males with PTSD had a higher BAD compared to both young and old male controls [55]. However, older males with PTSD exhibited a lower BAD, contradicting growing evidence that PTSD likely contributes to accelerated brain aging [55]. Like the previous study [86], this one was also limited by the young average and broad age range of participants, with an average age of 35.6 years, a stage at which significant neurodegenerative changes are generally not prominent, making it difficult to accurately capture BAD [55]. Despite these intriguing preliminary results, the underlying mechanisms by which psychological trauma, such as PTSD, might disrupt healthy brain aging — particularly at a neurological level — remain unclear. Our study sample and design presented a unique opportunity to examine brain aging in regard to a homogenous traumatic experience, the 9/11 World Trade Center tragedy and its aftermath. Having an age-matched control group without PTSD who experienced the same trauma as their counterparts who with PTSD, allows us to isolate the effects of the psychological and physiological sequelae of PTSD rather than the less specific effects of trauma-exposure or environmental toxic exposures. This minimizes potential confounding external variables between groups, providing more support for a causal inference and overall validity of our results.

Limitations of our study design include the small sample size and lack of an external control group (non-WTC). A larger sample size might improve statistical power. While a strong effort was made to increase the recruitment of underrepresented populations including women and people of color to the point of doubling the numbers of both in this sample compared to the responder population enrolled in our program [37, 49, 58], our sample could nevertheless benefit from improved diversity in order to facilitate subgroup analyzes that are out of reach of this study. The age range of WTC-responders included in this study (mean age of 55 years, ranging from 44 to 65) might be considered a limitation to the generalizability of our results as other PTSD studies typically focus on younger-aged groups rather than late adulthood. However, less is known about the effect of PTSD on the brain in individuals in this later stage of life and there is a need for more studies in this understudied age category. The exposure questionnaire, from which we gather self-reported experience during WTC rescue and recovery efforts, was often first administered years after 9/11 experiences were completed and may therefore be subject to recall bias. Although WTC exposure was used as the index trauma in this study, comprehensive data on participants’ prior trauma histories for this cohort were not available. As a result, we cannot rule out the potential influence of other trauma exposures on the observed outcomes, and this limitation further underscores that our findings are correlational in nature and do not support causal inferences. Finally, we lack accurate assessments of life trauma and/or PTSD status and MRI scans in WTC responders prior to 9/11, and we lack a comparison group of responders with subsyndromal, mild, heterogeneous, or remitted PTSD. Additionally, the lack of data on traumas endorsed prior to or following the 9/11 efforts (i.e., Criterion A) limits our ability to examine the potential compounding effects of cumulative trauma exposure on differences in BAD between groups. The complexity of factors influencing brain aging, such as toxic exposures, physical health comorbidities, and barriers to care, may interact in several ways with PTSD progression in this cohort. While these limitations may reduce the generalizability of these findings to the broader population, it is important to recognize that individuals exposed to traumatic circumstances often differ from the general population in meaningful ways - psychologically, socially, and biologically. As such, studying trauma-exposed populations provides unique and essential insight that may not be captured in the general population. In this study, the relationship between PTSD and brain age was assessed cross-sectionally at a single time point. Thus, we cannot infer causality or determine the directionality of the relationship between PTSD and potential accelerated brain aging. Future studies could benefit from examining PTSD and brain aging longitudinally in similarly homogeneous cohorts, which could help clarify the temporal dynamics of this association while minimizing some of the confounding factors present in this dataset.

To conclude, this is the first study to investigate the link between PTSD and brain aging, highlighting the impact of traumatic stressors in WTC responders. We successfully derived Brain Age Difference (BAD) from MR imaging using a novel convolutional neural network to compute brain age in a PTSD population. Our results suggest that responders who developed WTC-related PTSD present significantly accelerated brain aging compared to non-PTSD responders. This effect was consistent across three different brain age prediction methods, underscoring the robustness and generalizability of the finding. BAD is correlated with volumes of specific brain areas previously shown to be associated with aging and PTSD. Finally, brain age is associated with WTC-exposure. By offering a reliable biomarker to assess aging trajectories, this study expands our understanding of the neurobiological impact of PTSD in WTC responders and highlights the broader potential of “brain age” to inform targeted individual and public health interventions aimed at promoting healthy brain aging across the lifespan.

Data availability

De-identified data will be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author; raw image files can be accessed upon completion of a data use agreement.

References

Azofeifa A. World Trade Center Health Program — United States, 2012−2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2021;70:1–21.

Liu B, Tarigan LH, Bromet EJ, Kim H. World Trade Center disaster exposure-related probable posttraumatic stress disorder among responders and civilians: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101491.

Alegría M, Fortuna LR, Lin JY, Norris FH, Gao S, Takeuchi DT, et al. Prevalence, risk, and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder across ethnic and racial minority groups in the U.S. Med Care. 2013;51:1114.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR. (2022).

O’Donovan A, Ahmadian AJ, Neylan TC, Pacult MA, Edmondson D, Cohen BE. Current posttraumatic stress disorder and exaggerated threat sensitivity associated with elevated inflammation in the Mind Your Heart Study. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;60:198–205.

O’Donovan A, Chao LL, Paulson J, Samuelson KW, Shigenaga JK, Grunfeld C, et al. Altered inflammatory activity associated with reduced hippocampal volume and more severe posttraumatic stress symptoms in Gulf War veterans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:557–66.

O’Donovan A, Sun B, Cole S, Rempel H, Lenoci M, Pulliam L, et al. Transcriptional control of monocyte gene expression in post-traumatic stress disorder. Dis Markers. 2011;30:123–32.

Pace TWW, Wingenfeld K, Schmidt I, Meinlschmidt G, Hellhammer DH, Heim CM. Increased peripheral NF-κB pathway activity in women with childhood abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:13–17.

Bourassa KJ, Garrett ME, Caspi A, Dennis M, Hall KS, Moffitt TE, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder, trauma, and accelerated biological aging among post-9/11 veterans. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14:1–8.

Miller MW, Sadeh N. Traumatic stress, oxidative stress and post-traumatic stress disorder: neurodegeneration and the accelerated-aging hypothesis. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:1156–62.

Aiello AE, Dowd JB, Jayabalasingham B, Feinstein L, Uddin M, Simanek AM, et al. PTSD is associated with an increase in aged T cell phenotypes in adults living in Detroit. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;67:133.

Wolf EJ, Morrison FG. Traumatic stress and accelerated cellular aging: from epigenetics to cardiometabolic disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:75.

Wolf EJ, Miller MW, Hawn SE, Zhao X, Wallander SE, McCormick B, et al. Longitudinal study of traumatic-stress related cellular and cognitive aging. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;115:494–504.

Wolf EJ, Logue MW, Hayes JP, Sadeh N, Schichman SA, Stone A, et al. Accelerated DNA methylation age: Associations with PTSD and neural integrity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:155–62.

Kuan P-F, Ren X, Clouston S, Yang X, Jonas K, Kotov R, et al. PTSD is associated with accelerated transcriptional aging in World Trade Center responders. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:1–8.

Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, Barnes D, Covinsky KE, Neylan T, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:608–13.

Desmarais P, Weidman D, Wassef A, Bruneau MA, Friedland J, Bajsarowicz P, et al. The interplay between post-traumatic stress disorder and dementia: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:48–60.

Felmingham K, Williams LM, Whitford TJ, Falconer E, Kemp AH, Peduto A, et al. Duration of posttraumatic stress disorder predicts hippocampal grey matter loss. Neuroreport. 2009;20:1402–6.

Bremner JD, Randall P, Scott TM, Bronen RA, Seibyl JP, Southwick SM, et al. MRI-based measurement of hippocampal volume in patients with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:973–81.

Apfel BA, Ross J, Hlavin J, Meyerhoff DJ, Metzler TJ, Marmar CR, et al. Hippocampal volume differences in Gulf War veterans with current versus lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:541–8.

Gurvits TV, Shenton ME, Hokama H, Ohta H, Lasko NB, Gilbertson MW, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging study of hippocampal volume in chronic, combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;40:1091–9.

Lindemer ER, Salat DH, Leritz EC, McGlinchey RE, Milberg WP. Reduced cortical thickness with increased lifetime burden of PTSD in OEF/OIF Veterans and the impact of comorbid TBI. Neuroimage Clin. 2013;2:601–11.

Wrocklage KM, Averill LA, Cobb Scott J, Averill CL, Schweinsburg B, Trejo M, et al. Cortical thickness reduction in combat exposed U.S. veterans with and without PTSD. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;27:515–25.

Wang X, Xie H, Chen T, Cotton AS, Salminen LE, Logue MW, et al. Cortical volume abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder: an ENIGMA-psychiatric genomics consortium PTSD workgroup mega-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:4331–43.

Mohamed AZ, Cumming P, Srour H, Gunasena T, Uchida A, Haller CN, et al. Amyloid pathology fingerprint differentiates post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;19:716–26.

Giesinger I, Li J, Takemoto E, Cone JE, Farfel MR, Brackbill RM. Association between posttraumatic stress disorder and mortality among responders and civilians following the September 11, 2001, disaster. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e1920476.

Clouston SA, Kotov R, Pietrzak RH, Luft BJ, Gonzalez A, Richards M, et al. Cognitive impairment among World Trade Center responders: Long-term implications of re-experiencing the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Alzheimer’s Dement (Amst, Neth). 2016;4:67–75.

Clouston S, Pietrzak RH, Kotov R, Richards M, Spiro A 3rd, Scott S, et al. Traumatic exposures, posttraumatic stress disorder, and cognitive functioning in World Trade Center responders. Alzheimer’s Dement (N. Y, N. Y). 2017;3:593–602.

Clouston SAP, Hall CB, Kritikos M, Bennett DA, DeKosky S, Edwards J, et al. Cognitive impairment and World Trade Centre-related exposures. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;18:103–16.

Huang C, Kritikos M, Sosa MS, Hagan T, Domkan A, Meliker J, et al. World Trade Center site exposure duration is associated with hippocampal and cerebral white matter neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol. 2023;60:160–70.

Huang C, Hagan T, Kritikos M, Suite D, Zhao T, Carr MA, et al. Graph theory-based analysis reveals neural anatomical network alterations in chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Imaging Neurosci. 2024;2:141 https://doi.org/10.1162/imag_a_00141.

Kritikos M, Clouston SAP, Huang C, Pellecchia AC, Mejia-Santiago S, Carr MA, et al. Cortical complexity in world trade center responders with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:1–10.

Invernizzi A, Rechtman E, Curtin P, Papazaharias DM, Jalees M, Pellecchia AC, et al. Functional changes in neural mechanisms underlying post-traumatic stress disorder in World Trade Center responders. Transl Psychiatry. 2023;13:239.

Weisenbach SL, Clouston SAP, Kaufman JR, Koppelmans V, Langenecker SA, Pellecchia AC, et al. 65 The impact of PTSD and mild cognitive impairment on resting state brain functional connectivity in World Trade Center responders. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2023;29:849–50.

Deri Y, Clouston SAP, DeLorenzo C, Gardus JD 3rd, Horton M, Tang C, et al. Selective hippocampal subfield volume reductions in World Trade Center responders with cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s Dement (Amst, Neth). 2021;13:e12165.

Deri Y, Clouston SAP, DeLorenzo C, Gardus JD 3rd, Bartlett EA, et al. Neuroinflammation in World Trade Center responders at midlife: A pilot study using [F]-FEPPA PET imaging. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;16:100287.

Clouston SAP, Deri Y, Horton M, Tang C, Diminich E, DeLorenzo C, et al. Reduced cortical thickness in World Trade Center responders with cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s Dement: Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2020;12:e12059.

Mann FD, Clouston SAP, Cuevas A, Waszczuk MA, Kuan PF, Carr MA, et al. Genetic liability, exposure severity, and post-traumatic stress disorder predict cognitive impairment in World Trade Center responders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;92:701–12.

Chen APF, Clouston SAP, Kritikos M, Richmond L, Meliker J, Mann F, et al. A deep learning approach for monitoring parietal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease in World Trade Center responders at midlife. Brain Commun. 2021;3:fcab145.

Clouston SAP, Kritikos M, Deri Y, Horton M, Pellecchia AC, Santiago-Michels S, et al. A cortical thinning signature to identify World Trade Center responders with possible dementia. Intell-Based Med. 2021;5:100032.

Elliott ML, Belsky DW, Knodt AR, Ireland D, Melzer TR, Poulton R, et al. Brain-age in midlife is associated with accelerated biological aging and cognitive decline in a longitudinal birth cohort. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:3829–38.

Cole JH, Franke K. Predicting age using neuroimaging: innovative brain ageing Biomarkers. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:681–90.

Cole JH, Ritchie SJ, Bastin ME, Valdés Hernández MC, Muñoz Maniega S, Royle N, et al. Brain age predicts mortality. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;23:1385–92.

World Trade Center Health Program. https://www.cdc.gov/wtc/.

Dasaro CR, Holden WL, Berman KD, Crane MA, Kaplan JR, Lucchini RG, et al. Cohort profile: World Trade Center health program general responder cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:e9.

Brackbill RM, Kahn AR, Li J, Zeig-Owens R, Goldfarb DG, Skerker M, et al. Combining three cohorts of World Trade Center rescue/recovery workers for assessing cancer incidence and mortality. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1386.

Luft BJ, Schechter C, Kotov R, Broihier J, Reissman D, Guerrera K, et al. Exposure, probable PTSD and lower respiratory illness among World Trade Center rescue, recovery and clean-up workers. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1069.

Gorgens KA Structured Clinical Interview For DSM-IV (SCID-I/SCID-II). In: Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 2410–7.

Clouston SAP, Diminich ED, Kotov R, Pietrzak RH, Richards M, Spiro A 3rd, et al. Incidence of mild cognitive impairment in World Trade Center responders: Long-term consequences of re-experiencing the events on 9/11/2001. Alzheimer’s Dement (Amst, Neth). 2019;11:628–36.

Hoopes A, Mora JS, Dalca AV, Fischl B, Hoffmann M. SynthStrip: skull-stripping for any brain image. Neuroimage. 2022;260:119474.

Avants, B, Tustison, NJ, Song, G Advanced Normalization Tools: V1.0. Insight J. (2009) https://doi.org/10.54294/uvnhin.

La Rosa F, Dos Santos Silva J, Dereskewicz E, Invernizzi A, Cahan N, Galasso J, et al. BrainAgeNeXt: advancing brain age modeling for individuals with multiple sclerosis. Imaging Neurosci (Camb). 2025;3:imag_a_00487 https://doi.org/10.1162/imag_a_00487. PMID: 40800843; PMCID: PMC12319810.

Roy, S, Koehler G, Ulrich C, Baumgartner M, Petersen J, Isensee F, et al. MedNeXt: Transformer-driven Scaling of ConvNets for Medical Image Segmentation. (2023).

Franke K, Gaser C. Ten years of BrainAGE as a neuroimaging biomarker of brain aging: what insights have we gained?. Front Neurol. 2019;10:789.

Clausen AN, Fercho KA, Monsour M, Disner S, Salminen L, Haswell CC, et al. Assessment of brain age in posttraumatic stress disorder: Findings from the ENIGMA PTSD and brain age working groups. Brain Behav. 2022;12:e2413.

Leonardsen EH, Peng H, Kaufmann T, Agartz I, Andreassen OA, Celius EG, et al. Deep neural networks learn general and clinically relevant representations of the ageing brain. Neuroimage. 2022;256:119210.

Billot B, Greve DN, Puonti O, Thielscher A, Van Leemput K, Fischl B, et al. SynthSeg: Segmentation of brain MRI scans of any contrast and resolution without retraining. Med Image Anal. 2023;86:102789.

Clouston SAP, Guralnik JM, Kotov R, Bromet EJ, Luft BJ. Functional limitations among responders to the World Trade Center attacks 14 years after the disaster: implications of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2017;30:443–52.

Diminich ED, Clouston SAP, Kranidis A, Kritikos M, Kotov R, Kuan P, et al. Chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid cognitive and physical impairments in World Trade Center responders. J Trauma Stress. 2021;34:616–27.

Mukherjee S, Clouston S, Kotov R, Bromet E, Luft B. Handgrip Strength of World Trade Center (WTC) responders: the role of re-experiencing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1128.

Pellecchia A, Kritikos M, Guralnik J, Ahuvia I, Santiago-Michels S, Carr M, et al. Physical functional impairment and the risk of incident mild cognitive impairment in an observational study of world trade center responders. Neurol Clin Pr. 2022;12:e162–e171.

Marchese S, Cancelmo L, Diab O, Cahn L, Aaronson C, Daskalakis NP, et al. Altered gene expression and PTSD symptom dimensions in World Trade Center responders. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:2225–46.

Cook JM, Simiola V. Trauma and Aging. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2018;20:93.

Kanasi E, Ayilavarapu S, Jones J. The aging population: demographics and the biology of aging. Periodontol 2000. 2016;72:13–18.

Todd KL, Brighton T, Norton ES, Schick S, Elkins W, Pletnikova O, et al. Ventricular and periventricular anomalies in the aging and cognitively impaired brain. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:445.

Zhou L, Li Y, Sweeney EM, Wang XH, Kuceyeski A, Chiang GC, et al. Association of brain tissue cerebrospinal fluid fraction with age in healthy cognitively normal adults. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1162001.

Chiu C, Miller MC, Caralopoulos IN, Worden MS, Brinker T, Gordon ZN, et al. Temporal course of cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and amyloid accumulation in the aging rat brain from three to thirty months. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2012;9:1–8.

Matsumae M, Kikinis R, Mórocz IA, Lorenzo AV, Sándor T, Albert MS, et al. Age-related changes in intracranial compartment volumes in normal adults assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:982–91.

Nestor SM, Kikinis R, Mórocz IA, Lorenzo AV, Sándor T, Albert MS, et al. Ventricular enlargement as a possible measure of Alzheimer’s disease progression validated using the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative database. Brain. 2008;131:2443–54.

Ott BR, Cohen RA, Gongvatana A, Okonkwo OC, Johanson CE, Stopa EG, et al. Brain ventricular volume and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:647–57.

Abdel-Rahman A, Shetty AK, Abou-Donia MB. Disruption of the blood-brain barrier and neuronal cell death in cingulate cortex, dentate gyrus, thalamus, and hypothalamus in a rat model of Gulf-War syndrome. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:306–26.

Yoshii T. The role of the thalamus in post-traumatic stress disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:1730.

Yang B, Jia Y, Zheng W, Wang L, Qi Q, Qin W, et al. Structural changes in the thalamus and its subregions in regulating different symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2023;335:111706.

Kritikos M, Huang C, Clouston SAP, Pellecchia AC, Santiago-Michels S, Carr MA, et al. DTI connectometry analysis reveals white matter changes in cognitively impaired World Trade Center responders at midlife. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;89:1075.

Bromet EJ, Hobbs MJ, Clouston SA, Gonzalez A, Kotov R, Luft BJ. DSM-IV post-traumatic stress disorder among World Trade Center responders 11-13 years after the disaster of 11 September 2001 (9/11). Psychol Med. 2016;46:771–83.

Kritikos M, Gandy SE, Meliker JR, Luft BJ, Clouston SAP. Acute versus chronic exposures to inhaled particulate matter and neurocognitive dysfunction: pathways to Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78:871–86.

Gavett SH. World Trade Center fine particulate matter–chemistry and toxic respiratory effects: an overview. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:971.

Landrigan PJ, Lioy PJ, Thurston G, Berkowitz G, Chen LC, Chillrud SN, et al. Health and environmental consequences of the world trade center disaster. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:731.

Cho J, Sohn J, Noh J, Jang H, Kim W, Cho SK, et al. Association between exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and brain cortical thinning: The Environmental Pollution-Induced Neurological EFfects (EPINEF) study. Sci Total Environ. 2020;737:140097.

Wyss-Coray T. Ageing, neurodegeneration and brain rejuvenation. Nature. 2016;539:180–6.

Ran C, Yang Y, Ye C, Lv H, Ma T. Brain age vector: A measure of brain aging with enhanced neurodegenerative disorder specificity. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43:5017–31.

Hou Y, Dan X, Babbar M, Wei Y, Hasselbalch SG, Croteau DL, et al. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:565–81.

Ballester PL, Romano MT, de Azevedo Cardoso T, Hassel S, Strother SC, Kennedy SH, et al. Brain age in mood and psychotic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;145:42–55.

Constantinides C, Han LKM, Alloza C, Antonucci LA, Arango C, Ayesa-Arriola R, et al. Brain ageing in schizophrenia: evidence from 26 international cohorts via the ENIGMA Schizophrenia consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;28:1201–9.

Shahab S, Mulsant BH, Levesque ML, Calarco N, Nazeri A, Wheeler AL, et al. Brain structure, cognition, and brain age in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;44:898–906.

Liang H, Zhang F, Niu X. Investigating systematic bias in brain age estimation with application to post-traumatic stress disorders. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:3143–52.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for supporting the neuroimaging study (CDC/NIOSH U01 OH011314), the National Institute on Aging that supports research on characterization and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (NIH/NIA P50 AG005138), and aging-relates work in this population (NIH/NIA R01 AG049953). We would also like to acknowledge ongoing funding to monitor World Trade Center responders as part of the WTC Health and Wellness Program (CDC 200-2011-39361). This research was partially funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Postdoc Mobility Fellowship (P500PB_206833) and Schmidt Sciences. This work was supported in part through the computational and data resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing and Data at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) grant UL1TR004419 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure of the National Institutes of Health under award number S10OD026880 and S10OD030463. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by the Icahn School of Medicine Capital Campaign, BioMedical Engineering and Imaging Institute, and Department of Radiology, as well as by the Intramural Research Program of NINDS, NIH. This work was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs through the Multiple Sclerosis Research Program under Award No. (HT9425-24-1-0857). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AI and FLR processed the data, performed the analyses, designed the figures, and drafted the manuscript. AS and ER contributed to the analyses and manuscript drafting. IN and RSM assisted with result interpretation. ACP and SS-M collected the data. EJB, RGL, BJL, SAC, ESB, and CY provided access to the WTC cohort dataset and contributed to interpreting the findings. MKH supervised the analyses and the final manuscript preparation. All authors discussed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Invernizzi, A., La Rosa, F., Sather, A. et al. MRI signature of brain age underlying post-traumatic stress disorder in World Trade Center responders. Transl Psychiatry 16, 23 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03769-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03769-7