Abstract

Background and purpose

Rapidly progressive dementia (RPD) represents a heterogeneous group of clinical dementia syndromes characterized by a precipitous decline in cognitive function, typically occurring over weeks to months, with diverse underlying etiologies. To elucidate the evolving etiological spectrum of RPD and investigate temporal trends, we conducted a comprehensive systematic review incorporating temporal subgroup analyses.

Method

English-language studies published prior to December 31, 2024 were searched in the Medline (PubMed), ISI Web of Science and the Cochrane Library databases. Study design, study period, patient characteristics, etiologies of RPD in each study were retrieved.

Result

We encompassed 13 studies in our final systematic review, involving a total of 1,701 patients with RPD. Our findings revealed that neurodegenerative diseases (459 cases, 27.0%), neuroimmune diseases (327 cases, 19.2%), and central nervous system infections (295 cases, 17.3%) represented the most prevalent etiological categories associated with RPD. Among distinct disease entities, autoimmune encephalitis (AE, 266 cases, 15.6%), Alzheimer’s disease (214 cases, 12.6%), and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (214 cases, 12.6%) were identified as the three most frequently observed etiologies of RPD. Temporally, neuroimmune diseases, particularly AE, exhibited a significant upward trend in prevalence over the study period.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the evolving etiological spectrum of RPD and emphasize the need for ongoing research and targeted diagnostic strategies to address the rising incidence of neuroimmune-related RPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rapidly progressive dementia (RPD) is a term commonly employed to characterize a cohort of cognitive disorders that exhibit a swift progression to dementia. While the precise definition of ‘rapidly’ may vary, it is generally agreed upon that the time span from the initial manifestation of disease-related symptoms to the development of dementia is typically within weeks to months, with the majority of patients reaching this stage within 1 to 2 years [1]. Owing to the significant heterogeneity in study design and the varying definitions utilized, the incidence and prevalence of RPD are subject to variation. In two single-center cohorts, approximately one-quarter of admitted patients with dementia were categorized as RPD, with specific figures of 24% (68/279) in Greece [2] and 27% (187/693) in India [3]. The occurrence rates of RPD among patients referred to the neurological department were 3.7% (61/1,648) in a tertiary hospital from Brazil [4], and 0.9% (149/15,731) in one from China [5].

RPD was first described and published in 1957, characterizing this syndrome within the context of demyelinating diseases [6]. Since its initial recognition, RPD has been increasingly identified across a spectrum of heterogeneous disorders, encompassing Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), atypically rapid forms of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs), central nervous system (CNS) infections, neuroimmune diseases, metabolic and toxic encephalopathies, and brain tumors. The most frequent symptoms at the onset of sporadic CJD were cognitive and visual impairment, myoclonus, cerebellar ataxia, and psychiatric symptoms. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) usually begins with memory deficit, cognitive decline, and psychiatric symptoms, whereas frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with behavioral changes and language deficits, Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) with motor dysfunction, cognitive impairment, and psychiatric symptoms. The most frequent initial symptoms of CNS infections were fever, headache, altered mental status, seizures, and cognitive impairment, while neuroimmune diseases, such as autoimmune encephalitis (AE), typically manifest with psychiatric symptoms, seizures, and cognitive impairment. With the exception of CJD and NDDs, the majority of RPD etiologies are amenable to treatment and potentially reversible. Consequently, early evaluation and prompt diagnosis of patients presenting with RPD are of paramount importance for precision treatment and improved prognosis.

The etiological factors contributing to RPD are multifaceted, which poses significant challenges to the prompt diagnosis and effective treatment. Prior studies have concentrated on elucidating the etiologies of RPD within cohorts of patients who were initially suspected of having RPD, however, the findings have been inconsistent. NDDs have been identified as the most frequent cause of RPD in certain studies [2, 7], whereas CNS infections or neuroimmune diseases have been found to predominate in other investigations [4, 8, 9]. In this context, we undertook a systematic review to clarify the evolving spectrum of etiologies associated with RPD and conducted a temporal-based grouping analysis to further investigate these trends.

Materials and methods

Study selection

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines for conducting a systematic review [10]. Two authors (MHL and LJC) independently searched all relevant articles in Medline (PubMed), ISI Web of Science and the Cochrane Library databases for the period prior to December 31, 2024. The search terms included “rapid* progressive dementia* [Title/Abstract] OR rapid* progressive cogniti* [Title/Abstract]”. The literature search was restricted to English-language studies involving human subjects. A comprehensive retrieval of all relevant articles was conducted, and their reference lists were meticulously reviewed to identify additional pertinent studies, thereby maximizing the pool of relevant literature. Given that all analyses were based on previously published studies, no ethical approval or patient consents were deemed necessary.

Eligibility criteria

The studies were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (i) the included cohort was restricted to RPD; (ii) original data from clinical studies; (iii) including various etiologies that cause RPD. The studies were excluded from the systematic review if they fulfilled the exclusion criteria: (i) single case reports or small case series (<10 cases) of RPD; (ii) data with significant selection bias, e.g. RPD cohorts from CJD referral centers had a pronounced selection bias favoring CJD.; (iii) in instances where the patient cohorts exhibited overlap across multiple articles, as determined through an assessment of sample origin and temporal period, only the study providing the most comprehensive information and possessing the largest sample size was selected for inclusion. The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using an 11-item assessment scale developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), which is specifically recommended for assessing cross-sectional studies [11]. Based on the total scores obtained, the studies were categorized into three quality levels: low quality (scoring 0-3), moderate quality (scoring 4-7), and high quality (scoring 8-11).

Data extraction and statistical analysis

All the studies were evaluated and examined carefully by 2 authors (RL and YEZ). The following data were retrieved for each study: author, publication year, country, study period, study design, sample size, gender, age, spectrum and frequency of clinical diagnoses in patients with RPD. Potential discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus with other authors. The included studies were divided into 3 groups according to the end time of study period: Group 1 (prior to 2012), Group 2 (2013 ~ 2017), and Group 3 (2018 ~ 2023). The current classification scheme was informed by the development of landmark diagnostic criteria for major RPD-related diseases (e.g. CJD in 2009 [12], AD in 2011 [13], AE in 2016 [14]), along with the publication timeline of the included studies. For descriptive statistics, categorical variables were expressed as percentages.

Results

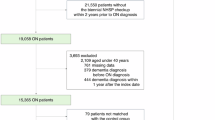

The PRISMA flowchart is displayed in Fig. 1. A total of 13 studies [2,3,4,5, 7,8,9, 15,16,17,18,19,20] encompassing 1,701 patients with RPD were included in our final systematic review. The mean/median age of RPD patients across the different studies varied from 48.0 to 72.4 years, and the proportion of female patients ranged from 34.8 to 63.9%. All of the 13 included studies were retrospective in study design. Geographically, five studies were conducted in Asia [3, 5, 8, 9, 20], four in Europe [2, 7, 15, 18] and the remaining four in America [4, 16, 17, 19]. The definition of RPD was based on the interval from the first disease-related symptom onset to the development of dementia being less than 1 year in seven studies [2, 3, 7, 8, 18,19,20] and less than 2 years in six studies [4, 5, 9, 15,16,17]. The diagnostic criteria of dementia was according to diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth or fifth edition (DSM-4/5) [21, 22] in six studies [2, 3, 7, 9, 17, 19], National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroup recommendations [13] in one study [4], not available in remaining six studies [5, 8, 15, 16, 18, 20]. Regarding the quality of the included studies, all achieved moderate to high quality, as detailed in Table 1.

Among the 1,701 patients, NDDs were the most common causes of RPD, accounting for 27.0% (459 patients) of cases. This category included AD (214 patients, 12.6%), FTD (110 patients, 6.5%), DLB (67 patients, 3.9%), neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease (NIID, 5 patients, 0.3%), and other NDDs (63 patients, 3.7%). Neuroimmune diseases of the CNS were the second most common causes of RPD, representing 19.2% (327 patients) of cases. This group comprised AE (266 patients, 15.6%), CNS vasculitis (26 patients, 1.5%), CNS demyelinating disease (16 patients, 0.9%), and other inflammatory disorders (19 patients, 1.1%). CNS infections were the third most common causes of RPD, making up 17.3% (295 patients) of cases, and included viral encephalitis (87, 5.1%), neurocysticercosis (66 patients, 0.9%), neurosyphilis (64 patients, 3.8%), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (11 patients, 0.6%), and other infections (67 patients, 3.9%). Other causes, ranked from most to least frequent, included CJD (214 patients, 12.6%), vascular dementia (VaD, 95 patients, 5.6%), metabolic or toxic diseases (95 patients, 5.6%), intracranial tumors (67 patients, 3.9%), normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH, 23 patients, 1.4%), hereditary diseases (12 patients, 0.7%), and cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation (CAA-RI, 8 patients, 0.5%), as depicted in Table 2 and Fig. 2. As distinct disease entities, AE, AD, and CJD represented the three most frequent etiologies of RPD.

Of the included studies, three studies were categorized into Group 1 (prior to 2012), seven studies into Group 2 (2013–2017), and the remaining three studies into Group 3 (2018–2023). In Group 1 studies, the top three most common causes of RPD were NDDs (60/154, 39.0%), CJD (35/154, 22.7%), and VaD (17/154, 11.0%). In Group 2, the top three most common causes were CNS infections (225/920, 24.5%), NDDs (214/920, 23.3%), and neuroimmune diseases (184/920, 20.0%). In Group 3, the top three most common causes were NDDs (185/627, 29.5%), neuroimmune diseases (127/627, 20.3%), and CJD (74/627, 11.8%). From a temporal perspective, neurosyphilis, neuroimmune diseases, AE, and metabolic or toxic diseases exhibited an upward trend, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

AD Alzheimer’s disease, AE Autoimmune encephalitis, CAA-RI Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation, CJD Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, CNS central nervous system, DLB dementia with Lewy bodies, FTD frontotemporal dementia, HIV human immunodeficiency virus; NDD, neurodegenerative disease, NIID neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease, NPH normal pressure hydrocephalus, VaD vascular dementia.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we undertook an extensive investigation into the etiologies of RPD, and our findings revealed that NDDs were the predominant causes of RPD, both in the overall analysis and across various temporal cohorts. AD was the most prevalent type of NDDs, and emerged as the second most prevailing disease entity responsible for RPD. AD typically manifest as a chronically progressive clinical course. The term rapidly progressive AD has been introduced to designate AD patients with a swift progression of dementia. The synergistic interaction of Aβ, tau, and neuroinflammation (particularly microglia activation) creates an amplifying cascade effect termed pathological storm, leading to rapid cognitive decline and dementia [23]. The prevalence of rapidly progressive AD varied among studies, accounting for approximately 10 to 30% of patients with AD, thereby illustrating that this subtype of AD is not an infrequent occurrence [24, 25]. Rapidly progressive AD has been identified as being associated with an earlier occurrence of non-cognitive symptoms, extrapyramidal motor disturbances, and lower amyloid-beta (Aβ) 1–42 concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [26]. With the advancement of disease-modifying therapies for AD, early diagnosis and prompt initiation of anti-amyloid immunotherapy may potentially delay disease progression and improve the prognosis. Due to the high incidence and substantial disease burden of NDDs, even a small proportion of patients presenting with rapid cognitive decline accounts for a significant percentage of total RPD cases [27]. For elderly RPD patients presenting with neuropsychiatric symptoms, language impairment, or motor dysfunction, the possibility of rapidly progressive NDDs should always be considered.

NIID has not been recognized as a frequent cause of RPD, accounting for 0.3% of all included cases, but up to 2.7% in a recent Chinese cohort of RPD [5]. The diagnosis of NIID has historically relied on post-mortem pathological findings, which has constrained the number of reported cases. However, with the identification of characteristic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings and intranuclear inclusions in skin biopsy, the number of confirmed cases has increased rapidly in recent years [28, 29]. The discovery of GGC-repeat expansions in the NOTCH2NLC gene associated with NIID has further facilitated diagnosis and understanding of the disease. Although the clinical manifestations of NIID are highly heterogeneous, progressive cognitive impairment emerges as the most prevalent clinical feature [28, 29]. Consequently, NIID may be an underrecognized cause of RPD. In RPD patients presenting with autonomic dysfunction, episodic neurogenic events, or movement disorders, particularly those exhibiting corticomedullary hyperintensities on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), NIID should be entertained as a differential diagnosis.

Despite its rarity, CJD remains a crucial consideration in the context of RPD. As a distinct disease entity, CJD tied with AD for the second most frequent etiologies of RPD in our study. Patients with CJD typically present with a constellation of clinical features, including rapidly progressive cognitive decline, cerebellar ataxia, myoclonus, and pyramidal and extrapyramidal signs [30]. The identification of characteristic hyperintensities in the cerebral cortex (referred to as “cortical ribboning”), basal ganglia, and thalamus on DWI of brain MRI, the detection of 14–3–3 proteins in CSF, and the presence of periodic sharp and slow wave complexes on electroencephalogram (EEG) have collectively enhanced the diagnostic convenience and efficiency. The recently developed real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) assay is a highly sensitive and specific method for detecting misfolded prion protein (PrPSc) in CSF, thereby providing a robust and reliable diagnostic tool for sporadic CJD [31]. The incidence and prevalence of CJD has increased over the past few decades, probably due to the improved diagnostic techniques. Consequently, for patients presenting with RPD and other associated clinical manifestations, as well as characteristic paraclinical features, the possibility of CJD should always be considered.

In our study, neuroimmune diseases of the CNS constituted the second most prevalent etiological group for RPD, with AE emerging as the most frequent specific disease entity within this category. AE is a group of non-infectious inflammatory disorders of the CNS, characterized by autoantibodies directed against neuronal cell-surface and synaptic antigens, and intracellular antigens. Patients with AE typically present with acute or subacute onset of cognitive impairment, psychiatric symptoms, epileptic seizures, movement disorders, and symptoms involving the brainstem and cerebellum [32]. The diagnosis of AE relies on a combination of typical clinical manifestations, alterations in MRI, CSF, and EEG, and the detection of autoantibodies [14]. Over the past two decades, the incidence rate of AE has been increasing, which is consistent with our results. This upward trend is multifactorial, primarily driven by the progressive expansion of the antibody spectrum, the widespread adoption and improvement of antibody detection techniques, and the heightened vigilance and diagnostic acumen of clinicians in recognizing and managing AE [33].

In the study, CNS infections emerged as the third most prevalent etiological category contributing to RPD. CNS infections can trigger or accelerate neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment through multiple interconnected mechanisms, primarily involving neuroinflammation, microglial activation, direct neuronal damage, blood-brain barrier disruption, protein misfolding (amyloid β and Tau protein), and systemic immune dysregulation [34, 35]. Among these etiologies, viral encephalitis, neurocysticercosis, and neurosyphilis were identified as the predominant causative agents of RPD. Viral infections remain the most common etiologic agents of encephalitis globally, with herpesviruses, arboviruses, enteroviruses, and respiratory viruses being the primary causative pathogens [36]. For instance, herpes simplex virus encephalitis most frequently affects the medial temporal and insular lobes, and typically presents with fever, headache, behavioral changes, cognitive impairment, and seizures [37]. Neurocysticercosis and other parasitic infections of CNS contributed to the burden of RPD, particularly in less developed countries, including Latin America, Africa, and large parts of Asia. With increased migration from endemic to nonendemic regions, cases of neurocysticercosis are being observed with greater frequency in areas where it is previously uncommon, which necessitates heightened awareness and vigilance among clinicians in nonendemic regions [38]. The incidence of neurosyphilis has been increasing in recent years, paralleling the overall rise in the rates of syphilis over the past two decades [39]. This trend is consistent with our finding and highlights the need for enhanced surveillance and targeted interventions, particularly among high-risk populations such as men who have sex with men and individuals living with HIV. As a classic manifestation of late neurosyphilis, progressive dementia with an insidious onset typically develops decades after the initial infection [40]. Abnormal findings of serum and CSF serologic tests, along with elevated CSF white-cell count and protein concentration, collectively contribute to the diagnosis of neurosyphilis.

Metabolic or toxic diseases, VaD, and intracranial tumors each accounted for approximately 5% of RPD. Less frequently, NPH and hereditary diseases each accounted for around 1% of RPD. Although uncommon, these disorders should be included in the differential diagnosis of RPD. Lastly, CAA-RI emerged as a rare etiology of RPD. CAA-RI is a rare subtype of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy, characterized by spontaneous perivascular inflammation in the context of amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition within the cerebral blood vessels. In a systematic review and meta-analysis comprising 378 patients, cognitive decline (70%) was the most common clinical manifestation, and white matter T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintensities and lobar cerebral microbleeds were identified as the most prevalent MRI findings [41]. Considering that CAA-RI constituted merely 0.5% of RPD in our study, and that most studies lacked inclusion of patients with CAA-RI, it is likely that this condition has been under-recognized and underdiagnosed in clinical settings. A definite diagnosis of CAA-RI necessitates histopathologic findings, while a probable or possible diagnosis can be established based on the combination of clinical features and brain MRI characteristics [42, 43]. Early diagnosis and prompt initiation of immunosuppressive therapy may improve the clinical outcome.

The strength of this study is the relatively large number, but as a systematic review, our study has certain limitations. First, there was potential publication bias, since all the data were obtained from openly published literatures. Second, all included studies employed retrospective designs, rendering them susceptible to various biases (particularly selection bias), as well as issues of inconsistency and imprecision. Although the AHRQ scale rated the methodological quality of included studies as moderate to high, the overall certainty of evidence—as evaluated by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system [44]—was assessed to be low to very low. Third, the intervals from the first symptom onset to the development of dementia in the definition of RPD were different among these studies, which might lead to potential bias.

Conclusion

Our systematic review encompassed 13 studies involving a total of 1,701 patients with RPD, revealing that NDDs, neuroimmune diseases, and CNS infections constituted the most prevalent etiological categories underlying RPD. As distinct disease entities, AE, AD, and CJD emerged as the three most frequently identified etiologies of RPD. From a temporal perspective, neuroimmune diseases, particularly AE, demonstrated a marked upward trend in prevalence over time. These findings suggest a shifting etiological landscape in RPD and emphasize the growing importance of immune-mediated causes in its diagnosis and management. It is noteworthy that all studies included in this systematic review are retrospective in design and thus susceptible to bias, inconsistency, and imprecision. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution, and future large-scale prospective studies are needed to validate our results.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no new datasets were generated during the current study. The data that support the findings of this study were derived from public domain resources as referenced.

References

Hermann P, Zerr I. Rapidly progressive dementias - aetiologies, diagnosis and management. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022;18:363–76.

Papageorgiou SG, Kontaxis T, Bonakis A, Karahalios G, Kalfakis N, Vassilopoulos D. Rapidly progressive dementia: causes found in a Greek tertiary referral center in Athens. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:337–46.

Anuja P, Venugopalan V, Darakhshan N, Awadh P, Wilson V, Manoj G, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia: an eight year (2008-16) retrospective study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e189832.

Studart NA, Soares NH, Simabukuro MM, Solla DJF, Goncalves MRR, Fortini I, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia: prevalence and causes in a neurologic unit of a tertiary hospital in brazil. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2017;31:239–43.

Liu X, Sun Y, Zhang X, Liu P, Zhang K, Yu L, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of rapidly progressive dementia: a retrospective cohort study in a neurologic unit in China. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:142.

Bergin JD. Rapidly progressing dementia in disseminated sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:285–92.

Sala I, Marquie M, Sanchez-Saudinos MB, Sanchez-Valle R, Alcolea D, Gomez-Anson B, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia: experience in a tertiary care medical center. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:267–71.

Chandra SR, Viswanathan LG, Pai A, Wahatule R, Alladi S. Syndromes of rapidly progressive cognitive decline-our experience. J Neurosci Rural Pr. 2017;8:S66–71.

Zhang Y, Gao T, Tao QQ. Spectrum of noncerebrovascular rapidly progressive cognitive deterioration: a 2-year retrospective study. Clin Inter Aging. 2017;12:1655–9.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Sy R, Garritty C et al. Celiac disease. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004. Evidence reports/technology assessments, no. 104. Appendix D. Quality assessment forms https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK35156/.

Zerr I, Kallenberg K, Summers DM, Romero C, Taratuto A, Heinemann U, et al. Updated clinical diagnostic criteria for sporadic creutzfeldt-jakob disease. Brain. 2009;132:2659–68.

McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–9.

Graus F, Titulaer MJ, Balu R, Benseler S, Bien CG, Cellucci T, et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15:391–404.

Tagliapietra M, Zanusso G, Fiorini M, Bonetto N, Zarantonello G, Zambon A, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic criteria for sporadic creutzfeldt-jakob disease among rapidly progressive dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34:231–8.

Day GS, Musiek ES, Morris JC. Rapidly progressive dementia in the outpatient clinic: more than prions. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2018;32:291–7.

Acosta JN, Ricciardi ME, Alessandro L, Carnevale M, Farez MF, Nagel V, et al. Diagnosis of rapidly progressive dementia in a referral center in Argentina. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2020;34:54–58.

Stamatelos P, Kontokostas K, Liantinioti C, Giavasi C, Ioakeimidis M, Antonelou R, et al. Evolving causes of rapidly progressive dementia: a 5-year comparative study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2021;35:315–20.

Satyadev N, Tipton PW, Martens Y, Dunham SR, Geschwind MD, Morris JC, et al. Improving early recognition of treatment-responsive causes of rapidly progressive dementia: the STAM(3) P score. Ann Neurol. 2024;95:237–48.

Shi Q, Liu WS, Liu F, Zeng YX, Chen SF, Chen KL, et al. The etiology of rapidly progressive dementia: a 3-year retrospective study in a tertiary hospital in China. J Alzheimers Dis. 2024;100:77–85.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV fourth edition-text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Pascoal TA, Benedet AL, Ashton NJ, Kang MS, Therriault J, Chamoun M, et al. Microglial activation and tau propagate jointly across braak stages. Nat Med. 2021;27:1592–9.

Schmidt C, Wolff M, Weitz M, Bartlau T, Korth C, Zerr I. Rapidly progressive Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:1124–30.

Ba M, Li X, Ng KP, Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, Rosa-Neto P, et al. The prevalence and biomarkers’ characteristic of rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease from the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative database. Alzheimers Dement (N. Y.) 2017;3:107–13.

Herden JM, Hermann P, Schmidt I, Dittmar K, Canaslan S, Weglage L, et al. Comparative evaluation of clinical and cerebrospinal fluid biomarker characteristics in rapidly and non-rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15:106.

Wang S, Jiang Y, Yang A, Meng F, Zhang J. The expanding burden of neurodegenerative diseases: an unmet medical and social need. Aging Dis. 2024;16:2937–52.

Sone J, Mori K, Inagaki T, Katsumata R, Takagi S, Yokoi S, et al. Clinicopathological features of adult-onset neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Brain. 2016;139:3170–86.

Tai H, Wang A, Zhang Y, Liu S, Pan Y, Li K, et al. Clinical features and classification of neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease. Neurol Genet. 2023;9:e200057.

Zerr I, Ladogana A, Mead S, Hermann P, Forloni G, Appleby BS. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and other prion diseases. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2024;10:14.

Hermann P, Appleby B, Brandel JP, Caughey B, Collins S, Geschwin MD, et al. Biomarkers and diagnostic guidelines for sporadic creutzfeldt-jakob disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:235–46.

Lai QL, Cai MT, Zheng Y, Fang GL, Du BQ, Shen CH, et al. Evaluation of CSF albumin quotient in neuronal surface antibody-associated autoimmune encephalitis. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2022;19:93.

Varley JA, Strippel C, Handel A, Irani SR. Autoimmune encephalitis: recent clinical and biological advances. J Neurol. 2023;270:4118–31.

Kettunen P, Koistinaho J, Rolova T. Contribution of CNS and extra-CNS infections to neurodegeneration: a narrative review. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21:152.

Awan M, Mahmood F, Peng XB, Zheng F, Xu J. Underestimated virus impaired cognition-more evidence and more work to do. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1550179.

Gundamraj V, Hasbun R. Viral meningitis and encephalitis: an update. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2023;36:177–85.

Stahl JP, Mailles A. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis update. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2019;32:239–43.

Coyle CM, Bustos JA, Garcia HH. Current challenges in neurocysticercosis: recent data and where we are heading. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2024;37:313–9.

Hamill MM, Ghanem KG, Tuddenham S. State-of-the-art review: neurosyphilis. Clin Infect Dis. 2024;78:e57–68.

Ropper AH. Neurosyphilis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1358–63.

Theodorou A, Palaiodimou L, Malhotra K, Zompola C, Katsanos AH, Shoamanesh A, et al. Clinical, neuroimaging, and genetic markers in cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2023;54:178–88.

Grangeon L, Boulouis G, Capron J, Bala F, Renard D, Raposo N, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation and biopsy-positive primary angiitis of the CNS: a comparative study. Neurology. 2024;103:e209548.

Szalardy L, Fakan B, Maszlag-Torok R, Ferencz E, Reisz Z, Radics BL, et al. Identifying diagnostic and prognostic factors in cerebral amyloid angiopathy-related inflammation: A systematic analysis of published and seven new cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2024;50:e12946.

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:401–6.

Funding

This study was funded by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number LQ23H090004), Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (2023KY006, 2020KY396, 2023RC120, 2025KY525) and Zhejiang Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (2023ZL220).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MHL, QLL and SQ contributed to concept and design of the study. MHL, RL, YEZ, SRZ, LYZ, YJM and LC contributed to acquisition and analysis of the data. MHL and LJC contributed to drafting the initial manuscript. QLL and SQ contributed to revising the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, MH., Cao, LJ., Liu, R. et al. The evolving etiologies of rapidly progressive dementia: a systematic review. Transl Psychiatry 15, 535 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03777-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03777-7