Abstract

Chronic systemic inflammation is a key driver of polycythemia vera (PV) progression, but the immunomodulatory effects of current treatments remain poorly defined. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is an accessible biomarker of systemic inflammation proven in other contexts, but its role in monitoring PV disease activity has not been established. Using data from three of the largest PV clinical trials, we evaluated the effects of PV therapies on NLR and its relationship with molecular response and clinical outcomes. In 404 hematocrit-controlled patients from the ECLAP study, hydroxyurea (HU) failed to significantly lower NLR (p = 0.11) due to the parallel declines in ANC and ALC. Neither leukocyte counts nor NLR were significantly reduced by phlebotomy in ECLAP patients treated without cytoreductive therapy. In contrast, the Low-PV study showed that while phlebotomy tended to increase NLR, low-dose ropeginterferon alfa-2b (Ropeg) significantly reduced NLR (−18.2% and −36.3% in patients with low and high baseline NLR, respectively) by suppressing ANC rather than lymphocytes. NLR reduction correlated with the primary Low-PV endpoint (p = 0.021) and reduction of JAK2 variant allele frequency (VAF) [1]. The PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV study confirmed the superior effect of Ropeg over HU, with a significantly greater NLR reduction at 60 months (−56.5% versus −33.6%, respectively, p = 0.019) in patients with high baseline NLR. Moreover, NLR reduction was associated with decreased JAK2V617F VAF (p < 0.0001) and improved event-free survival (p = 0.010). These findings identify NLR as a dynamic biomarker of treatment response and prognosis in PV and support its incorporation into routine monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Standard therapy for all patients with polycythemia vera (PV) includes regular phlebotomy to maintain hematocrit below 45% and low-dose aspirin. Cytoreductive therapy is currently reserved for patients with higher thrombotic risk (age >60 years or prior thrombotic events), with hydroxyurea (HU) or pegylated interferon-alpha as first-line agents, and busulfan or ruxolitinib as second-line options [2,3,4]. All of these PV treatment strategies focus on reducing thrombotic events, the leading cause of mortality, yet emerging evidence highlights the role of chronic inflammation in the pathobiology of PV. Inflammation, driven by the JAK2 mutation present in over 95% of PV cases, is increasingly recognized as a key driver of leukocyte activation, thrombosis, disease progression, and reduced survival in this disease [5,6,7,8].

Neutrophils play a pivotal role in this process, promoting endothelial injury and thrombosis through the release of cytokines, reactive oxygen species, and neutrophil extracellular traps, thereby amplifying local and systemic inflammation [9,10,11]. Lymphocytes, particularly regulatory T cells and CD8 + T cells, modulate immune responses, with distinct subtypes influencing inflammatory pathways [12,13,14]. Both neutrophil counts and lymphocyte counts are directly affected by the presence of the JAK2V617F mutation found in virtually all patients with PV [15].

While absolute neutrophil count (ANC) and absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) have been linked to prognosis in essential thrombocythemia (ET) [16], and have also been validated in a cohort of patients with PV [17], the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) may provide a more integrated assessment of inflammatory burden by capturing both innate and adaptive immune activity [18]. NLR is a readily available and extensively studied biomarker with prognostic value in cardiovascular disease (e.g., prediction of myocardial infarction and stroke) and cancer (e.g., tumor progression and treatment resistance) [19]. Recent studies in PV also link elevated NLR to risk of venous thrombosis [20] and reduced overall survival [21].

This study uses prospective data from three of the largest PV clinical trials to evaluate whether NLR could serve as a dynamic biomarker of treatment response and clinical outcomes. We used data collected as part of the ECLAP study to compare hydroxyurea to phlebotomy in 404 propensity score matched patients with PV. Data from 126 low-risk PV patients enrolled on the randomized phase II Low-PV trial allowed comparison of the effects of Ropeginterferon alfa-2b (Ropeg) versus phlebotomy alone on leukocyte counts and NLR. Finally, data from the PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV study enabled a direct HU vs. Ropeg comparison, assessing NLR dynamics and its association with JAK2V617F VAF reduction and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Patients

Patient data were sourced from three databases tracking WBC, ANC, ALC, and NLR.

ECLAP Database [22]

Included 1638 PV patients treated with PHL or HU to maintain hematocrit <45% and platelet counts <400 × 10⁹/L, with annual follow-ups for up to 5 years. Only patients exclusively on PHL (n = 202) or HU (n = 202), appropriately matched by propensity score, were analyzed.

Low-PV Study [23, 24]

A randomized phase II trial of 127 PV patients assigned to PHL alone (n = 64) or Ropeg (100 μg every 2 weeks) plus PHL (n = 63) for 12 months.

PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV [25]

A phase III trial where PV patients received Ropeg (n = 127) or HU (n = 127) for 12 months, with response-driven dose escalation from 100 µg up to a maximum of 500 µg every 2 weeks (Ropeg) or up to 3,000 mg daily (HU). In the 5-year extension (CONTINUATION-PV), 88% of HU-treated patients remained on HU despite switching options.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In each study, patients provided written informed consent. In ECLAP study, approval of each local ethics committee was obtained before the start of the trial. Protocols for Low-PV (#NCT03003325), PROUD-PV (#NCT01949805) and CONTINUATION-PV (#NCT02218047) were approved by the relevant institutional review board or ethics committee at each participating institution according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Statistical methods

Analysis of data from the ECLAP and Low-PV cohorts was performed by A.G.; analysis of the PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV datasets was performed by the responsible biostatistician. All authors had access to primary clinical trial data.

To ensure comparability between the HU and PHL groups in the ECLAP database, propensity score (PS) matching was performed. A logistic regression model was used to estimate PS based on baseline covariates, including age, gender, years since diagnosis, prior thrombosis, aspirin use, smoking, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, platelet count, WBC count, hematocrit, and NLR. One-to-one nearest neighbor matching without replacement was applied, using a caliper width of 0.2 of the pooled standard deviation of the logit of PS.

Baseline characteristics of HU/PHL (ECLAP), Ropeg/PHL (Low-PV) and Ropeg/HU (PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV) groups were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Leukocyte-derived biomarkers were assessed in the full cohort and in the subgroup of patients with baseline values above the median.

Linear mixed-effects models with treatment, time and treatment-time interaction as fixed effects and patient as random intercept (to account for patient variability), were used to evaluate whether the temporal trend of each biomarker differed between the two treatments in each database. Moreover, changes in leukocyte-derived inflammatory biomarkers over time were reported as median relative changes, stratified by treatment and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate, where appropriate.

The impact of the inflammatory biomarkers on thrombosis and mortality risk in ECLAP database was assessed using multivariable Cox regression models adjusting for the effect of age, treatment received and cardiovascular risk factors. To account for their variation over time, the biomarkers were included as time-dependent variables. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.

To assess the robustness of the results, a joint modeling approach was used to simultaneously analyze biomarker trajectories and time to thrombosis/death. Biomarker evolution over time was modeled with a linear mixed-effects model (random intercept and slope, unstructured covariance) and for the survival submodel a Weibull proportional hazards model was used.

Median relative changes in JAK2V617F VAF at 12 months according to the extent of NLR reduction in patients treated with Ropeg was reported for PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV and Low-PV databases. Moreover, in PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV database, association between NLR at last assessment and risk events (thromboembolic events, disease progression to myelofibrosis or acute myeloid leukemia, or death) was performed as time to first event analysis (i.e. event-free survival, EFS) in subgroups based on NLR levels. The log-rank test was used to compare the group-specific Kaplan-Meier curves. Moreover, frequency of events was reported according to NLR groups.

Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA software (version 16; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and SAS 9.4.

Results

ECLAP Cohort

Baseline characteristics of PHL and HU groups after PS-matching

After 1:1 PS-matching, baseline characteristics of patients from the ECLAP cohort (Table S1) were analyzed. The matched groups were all maintained with HCT < 45% either by phlebotomy alone (PHL, N = 207) or with HU (500–1500 mg/day, N = 207). PS matching ensured that the two groups were well balanced across key variables including demographics, prior thrombosis, median time since PV diagnosis, duration of follow-up, cardiovascular risk-factors, and blood counts. The only exception was a clinically insignificant difference in baseline HCT.

Events during follow-up

After a median follow-up of 3 years (range 0.3–4.6) in the ECLAP study, outcomes and the effects of PHL or HU treatments on WBC, NLR, neutrophils, and lymphocytes were assessed at 12, 24, and 36 months. Total thromboses were registered in 44 patients (10.6%): of these, 24 events (5.8%) and 20 (4.8%) were arterial and venous, respectively. Disease progression was documented in 13 cases (3.1%): myelofibrosis in 11 (2.7%) and blast phase in 4 (1.0%). Solid tumors and deaths occurred in 18 (4.3%) and in 37 (8.9%) cases.

Effects of Phlebotomy and Hydroxyurea on Leukocyte Biomarkers

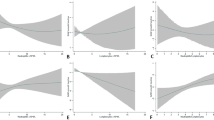

Figure 1 shows 36-month trends in WBC, NLR, ANC, and ALC across the overall ECLAP cohort and in subgroups with elevated baseline values. PHL had no significant effects on any measure at any time. HU modestly reduced WBC over time, but this was not significantly different from PHL (p = 0.71, Fig. 1A). Neither PHL nor HU significantly reduced NLR in the full cohort (p = 0.21) or in those with elevated baseline NLR ≥ 3.3 (p = 0.18, Fig. 1B). HU significantly reduced ANC (p = 0.020) in patients with baseline ANC ≥ 6.0 × 10⁹/L, confirming its cytoreductive effect, but ANC remained stable in the full ECLAP cohort (p = 0.54, Fig. 1C). ALC remained largely unchanged (p = 0.11); however, in patients with baseline ALC ≥ 1.8 × 10⁹/L, HU drove a noticeable decline at 12 and 24 months, whereas PHL had no significant effect (Fig. 1D). As a result, HU’s reduction of ANC was offset by a parallel decrease in ALC, leading to no significant impact on NLR in patients with elevated baseline values.

36-months trends of WBC (A), NLR (B), neutrophils (C), and lymphocytes (D) by treatment received in ECLAP database. The trend for the whole cohort and a focus on the subgroup of patients with high baseline values (above the median value) are reported in each panel. Global differences between the two treatments and differences over time were evaluated by a linear mixed-effect model with treatment, time and treatment-time interaction as fixed effects and patient as random intercept. *p-value for the main effect of treatment; **p-values for treatment-time interaction: a significant p-value indicates that the trend of each biomarker over time is different in the two arms, suggesting that the treatment affects how the parameter changes over time.

Figure S1 confirms these trends, showing that HU reduced WBC more significantly in patients with high baseline levels, where the relative reduction from baseline at 36 months was −27.4% compared to an increase of +5.2% in the PHL group (p < 0.001). While HU modestly lowered NLR (−10.4%) by 36 months, reductions in patients with high baseline NLR were not sustained. HU significantly reduced ANC, with the greatest decline (−32.6%) at 36 months in patients with baseline ANC ≥ 6.0 × 10⁹/L, whereas PHL had little effect (p < 0.001). ALC decline with HU was more pronounced at 12 and 24 months in patients with baseline ALC ≥ 1.8 × 10⁹/L but was not significantly different from PHL at 36 months (p = 0.19). HU lowered both ANC and ALC in parallel, limiting its ability to sustain NLR reduction. An initial NLR decline at 12 months, likely driven by ANC reduction, did not persist as ANC and ALC decreased together.

Impact leukocyte biomarkers on the risk of thrombosis and mortality

A multivariable Cox model (Fig. 2) showed that persistently high NLR ( ≥ 3.3) was significantly associated with increased mortality (HR: 3.59, p = 0.008) and total thrombosis (HR: 2.26, p = 0.013). As always, age was a risk factor for death (HR: 1.07, p = 0.001) and was borderline for thrombosis (p = 0.054). Cardiovascular risk factors strongly predicted thrombosis (HR: 4.92, p = 0.011). Changes in total WBC were not associated with these outcomes, highlighting NLR as a better risk predictor.

Estimates were obtained using a multivariable Cox regression model that included the effect of both WBC and NLR over time as time-dependent variables, adjusting for age, HU treatment, and cardiovascular (CV) risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, congestive heart failure, and smoking). Hazard ratios (HRs) for thrombosis (blue triangles) and mortality (red diamonds) were plotted with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (solid lines). In this model, total thromboses were considered, rather than separating arterial and venous thromboses, to ensure adequate statistical power.

These results were confirmed using a joint model, which showed that higher longitudinal NLR values were associated with increased thrombotic and mortality risk (Table S4). Each unit increase in NLR corresponded to a 10% increase in the risk of thrombosis (HR 1.10, 95% CI: 1.02–1.18, p = 0.010) and death (HR 1.10, 95% CI: 1.02–1.17, p = 0.012).

Low-PV Cohort

Baseline characteristics of PHL and Ropeg groups

Table S2 compares baseline characteristics in the Low-PV database between PHL- and Ropeg-treated patients. The Ropeg group had more males (73% vs. 62%) and a slightly higher median age (52 vs. 48 years). Cardiovascular risk factors were similar (48% vs. 55%), with comparable frequency of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes. Hematologic parameters, including hematocrit, platelet, and leukocyte counts, were also similar.

Trends Over Time in Leukocyte-Derived Biomarkers comparing PHL vs. Ropeg

Figure 3 shows 12-month trends in WBC, NLR, ANC, and ALC across the entire Low-PV cohort and in the subgroups with elevated baseline values. Across all patients, PHL had minimal effects on any of these measures but in those with elevated baseline values, WBC, ANC and NLR tended to increase over time. In contrast, Ropeg significantly reduced WBC, NLR, and ANC. WBC was stably reduced by Ropeg (p < 0.001), whereas PHL resulted in stable or slightly increasing levels. In patients with baseline WBC ≥ 8.8 × 10⁹/L, Ropeg produced a continuous decline, while PHL had little impact (p < 0.001, Fig. 3A). Ropeg progressively reduced NLR (p = 0.018), while PHL-treated patients showed stable or increasing values. In patients with baseline NLR ≥ 3.3, Ropeg’s effect was stronger, leading to a significant decline (p < 0.001, Fig. 3B), driven primarily by strong neutrophil suppression and relative lymphocyte sparing. Ropeg continuously suppressed ANC (p < 0.001), particularly in patients with baseline ANC ≥ 6.0 × 10⁹/L, where neutrophil levels declined progressively, while PHL had little effect or even a slight increase (Fig. 3C). Lymphocyte levels remained stable in both groups (p = NS, Fig. 3D).

12-months trends of WBC (A), NLR (B), neutrophils (C), and lymphocytes (D) by treatment received in Low-PV database. The trend for the whole cohort and a focus on the subgroup of patients with high baseline values (above the median value) are reported in each panel. Global differences between the two treatments and differences over time were evaluated by a linear mixed-effect model with treatment, time and treatment-time interaction as fixed effects and patient as random intercept. *p-value for the main effect of treatment; **p-values for treatment-time interaction: a significant p-value indicates that the trend of each biomarker over time is different in the two arms, suggesting that the treatment affects how the parameter changes over time.

Figure S2 confirms these trends, showing the relative changes in biomarkers from baseline. Ropeg reduced WBC by −45.5% overall and −46.8% in patients with baseline WBC ≥ 8.8 × 10⁹/L, while PHL increased WBC by +11.3% (p < 0.001), confirming Ropeg’s strong cytoreductive effect. Ropeg decreased NLR by −26.6% overall and −36.3% in patients with baseline NLR ≥ 3.3, whereas PHL increased NLR by +5.4% (p < 0.001). Ropeg reduced ANC by −50.9% overall and −56.7% in high ANC patients, while PHL increased ANC ( + 18.9%) (p < 0.001), explaining most of the NLR decline. Although Ropeg also reduced ALC (−32.0% overall, −37.0% in high ALC patients), the NLR drop resulted from the relatively stronger neutrophil suppression compared to lymphocyte depletion.

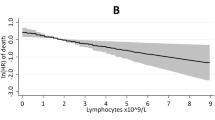

Correlation between changes in Leukocyte-Derived Biomarkers and JAK2V617F VAF

A significant correlation between changes in WBC, NLR, ANC and JAK2V617F allele burden (Pearson’s r = 0.43, r = 0.45 and r = 0.51; p < 0.001, p = 0.002 and p < 0.001) was found (Figure S4). In contrast, changes in ALC showed no statistically significant correlation with JAK2V617F VAF reduction (r = 0.20; p = 0.18), suggesting that the predictive utility of NLR is primarily driven by neutrophil dynamics. In the subgroup of patients with elevated baseline levels of inflammatory biomarkers, the same results were found (Figure S5).

Direct comparison of Ropeg versus HU within PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV studies

Baseline characteristics of HU and Ropeg groups

Baseline patient characteristics (i.e. at screening in PROUD-PV) among patients who enrolled in the long-term CONTINUATION-PV study are shown in Table S3. The treatment arms were well balanced regarding demographic and other parameters such as time since diagnosis of PV and JAK2V617F VAF.

Head-to-Head Comparative trajectories in Leukocyte-Derived Inflammatory Biomarkers

Figure 4 shows comparative 60-month trajectories in leukocyte-derived inflammatory biomarkers from the PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV trial, aligning with findings from ECLAP for HU and Low-PV for Ropeg. Ropeg led to a more sustained WBC reduction than HU in both the overall cohort and in patients with baseline WBC ≥ 10.9 × 10⁹/L (p < 0.001, Fig. 4A). Ropeg progressively reduced NLR, while HU showed an initial decline followed by an increase (p = 0.004, Fig. 4B), with a stronger effect in patients with baseline NLR ≥ 4.3. Ropeg also stably and progressively reduced ANC, whereas HU initially lowered ANC but this effect was lost over time (p < 0.001, Fig. 4C), particularly in patients with baseline ANC ≥ 7.8 × 10⁹/L. Both treatments reduced ALC, and although Ropeg had a greater effect initially, especially in patients with baseline ALC ≥ 1.8 × 10⁹/L (Fig. 4D), the difference with HU did not persist past 48 months.

60-months trends of NLR values by treatment received in PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV. The trend for the whole cohort and a focus on the subgroup of patients with high baseline values (above the median value) are reported in each panel. Global differences between the two treatments and differences over time were evaluated by a linear mixed-effect model with treatment, time and treatment-time interaction as fixed effects and patient as random intercept. *p-value for the main effect of treatment; **p-values for treatment-time interaction: a significant p-value indicates that the trend of NLR over time is different in the two arms, suggesting that the treatment affects how the parameter changes over time.

Figure S3 confirms these findings, showing relative changes from baseline in each biomarker. Ropeg induced a greater and more sustained WBC reduction than HU, with significant differences emerging from 24 months onward (p < 0.001). At 60 months, WBC decreased by −67.3% with Ropeg vs. −45.1% with HU (p < 0.001) in patients with baseline WBC ≥ 10.9×10⁹/L. Ropeg reduced NLR by −38.5% vs. −19.1% with HU (p = 0.045), with an even more pronounced effect in patients with baseline NLR ≥ 4.3. Ropeg also produced a deeper and sustained ANC reduction, achieving −65.8% vs. −44.4% with HU (p = 0.002), particularly in patients with baseline ANC ≥ 7.8 × 10⁹/L. Ropeg led to a greater ALC decline at 12 months (−37.8% vs. −28.4% with HU, p = 0.025), but at 60 months, ALC reductions with Ropeg (−34.7%) and HU (−30.3%) were not significantly different (p = 0.13). These results from this randomized, prospective clinical trial underscore Ropeg’s stronger impact on neutrophil suppression, its ability to modulate inflammation, and its capacity to better maintain lymphocyte balance compared to HU.

Correlation between NLR and JAK2V617F VAF levels

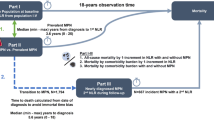

NLR was strongly associated with JAK2V617F VAF in the PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV cohort (p < 0.001), with greater NLR reductions correlating with larger JAK2V617F VAF declines at 12 months (Fig. 5A). A similar trend was observed in the Low-PV cohort (p = 0.002), where patients with unchanged NLR had only a minor JAK2 VAF reduction (−13.0%), while those with >50% NLR reduction showed the most significant VAF decline (−59.3%) (Fig. 5B).

Outcomes related to NLR in PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV

Event-free survival (EFS)—with events including thrombosis, progression to myelofibrosis/AML, or death—was significantly better in patients with NLR < 4.3 at the last assessment compared to those with NLR ≥ 4.3 (Log-rank p = 0.006) (Fig. 6). In this exploratory analysis, PV related events occurred in 9/44 vs. 8/125 patients in the high and low NLR groups, respectively (HR: 3.50, 95% CI 1.35–9.09, p = 0.010).

Association between NLR at last available assessment and the occurrence of risk events (thromboembolic events, disease progression to myelofibrosis or acute myeloid leukemia, or death) shown by time-to-first-risk-event analysis in subgroups based on NLR over or under the threshold of 4.3 (the median level recorded at baseline).

Figure 7 illustrates the frequency of events based on NLR dynamics. Patients with persistently low NLR had the lowest frequency (4.3%), while those with persistently high NLR had the highest (25.0%). Importantly, those with persistently high or rising NLR were significantly more likely to experience a PV event than those with persistently low or decreasing NLR (9/44, 20% vs. 8/125, 6.4%, Fisher’s p = 0.016, odds ratio 3.7-fold higher).

The figure shows the proportion of patients experiencing events based on NLR categories. Patients were categorized based on their baseline and final NLR values into four groups: (i) persistently low NLR (low NLR at baseline and at the final assessment), (ii) increasing NLR (low NLR at baseline but high NLR at the final assessment), (iii) decreasing NLR (high NLR at baseline but low NLR at the final assessment), and (iv) persistently high NLR (high NLR at both baseline and final assessment). The cutoff used to define high and low values corresponds to the median baseline NLR of 4.3.

Discussion

This study investigated the effects of PHL, HU and Ropeg on leukocyte-derived inflammatory biomarkers—WBC count, ANC, ALC and NLR—in three different large and balanced cohorts of patients with PV. The results provide valuable insights into how different treatment strategies modulate systemic inflammation, reported by NLR, and its potential impact on thrombotic risk and disease progression.

In both the ECLAP and Low-PV studies, PHL had minimal effect on inflammatory markers across the entire cohort, with WBC, ANC and NLR remaining stable or increasing over time, particularly in those with elevated baseline values. Unlike cytoreductive therapies, PHL did not meaningfully suppress ANC or lower NLR, reinforcing its limited role in inflammation control beyond HCT reduction. Notably, in patients with higher baseline WBC ( ≥ 8.8 × 10⁹/L) or ANC (ANC ≥ 6.0 × 10⁹/L), PHL-alone treated patients exhibited worsening inflammatory profiles over time, suggesting the need for cytoreduction in selected patients.

In contrast, HU demonstrated a modest ability to lower WBC counts, as seen in both the ECLAP and PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV studies, but its impact on systemic inflammation, as measured by NLR, was limited. In ECLAP, HU had a stronger effect on ANC suppression (particularly in patients with baseline ANC ≥ 6.0 × 10⁹/L, p < 0.001), but this was offset by concurrent ALC reductions, leading to no sustained change in NLR over time. Although HU initially lowered NLR in the first 12 months, this effect was not sustained at 24 or 36 months, with no significant difference vs. PHL (p = 0.53 and p = 0.11, respectively).

The PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV trial further confirmed these observations, showing that HU-treated patients exhibited only transient reductions in NLR, followed by a rebound. This inability to consistently suppress systemic inflammation suggests important clinical implications, as persistently high NLR after 12 months of HU therapy was associated with increased thrombosis risk (HR = 2.26, 95% CI 1.19–4.30) and worse survival (HR = 3.59, 95% CI 1.41–9.19). These findings contrast with sickle cell disease (SCD), where HU significantly reduces NLR and improves inflammatory profiles [26,27,28]. The likely explanation lies in fundamental differences in disease biology: in non-clonal disorders such as SCD, lymphocyte suppression is less pronounced, preserving adaptive immunity, whereas in PV, lymphocyte depletion is influenced by both HU and the JAK2V617F mutation itself [15]. The latter finding was derived from experimental animal models showing that JAK2V617F consistently blocks lymphoid differentiation from committed T and B cell precursors and is of particular importance for lymphopoiesis in JAK2V617F-driven clonal diseases such as PV. Over time, JAK2V617F-associated lymphopenia, which could also be a predictable consequence of long-term JAK2V617F MPNs regardless of therapy [15], may favor the emergence of abnormal lymphocyte subsets [29] and T-cell exhaustion [30], potentially promoting late complications associated with impaired immunity such as disease progression and solid tumors [31].

In contrast to both PHL and HU, Ropeg achieved a significant and sustained reduction in NLR, as demonstrated in both the Low-PV and PROUD-PV/CONTI-PV studies. Unlike HU, Ropeg’s ability to lower NLR was primarily driven by selective ANC suppression rather than broad leukocyte depletion, leading to a more favorable inflammatory balance. In the Low-PV trial, Ropeg-treated patients with baseline NLR ≥ 3.3 experienced a 36.3% reduction, compared to an increase with PHL (p < 0.001). This effect was sustained over time, particularly in patients with high baseline ANC ( ≥ 6.0 × 10⁹/L), where Ropeg produced continuous and significant ANC suppression while better preserving lymphocyte counts.

The PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV trial further validated Ropeg’s superiority over HU, showing that Ropeg led to a deeper and more sustained suppression of ANC and NLR. In patients with baseline NLR ≥ 4.3, Ropeg reduced NLR by 38.5% at 60 months vs. only 19.1% with HU (p = 0.027). Notably, this longitudinal pattern of NLR reduction mirrored the decline in JAK2V617F VAF, suggesting that Ropeg’s anti-inflammatory effects are directly linked to its ability to target clonal burden.

We also found a significant correlation between WBC/ANC changes and JAK2 VAF reflecting the proliferative myeloid component of PV that correlates with JAK2-driven myelopoiesis, but NLR captures the broader biological impact of the disease by integrating both innate immune activation (neutrophilia) and suppression of adaptive immunity (lymphopenia). This duality, driven by the JAK2V617F mutation [15], has been shown to correlate strongly and precisely with molecular response and clinical outcome.

Consistent with this interpretation are the findings in HU-treated patients in whom NLR remains elevated after 12 months of treatment. In the Cox multivariable analyses, the inclusion of NLR, but not leukocytosis, was independently associated with thrombosis and survival (HR = 2.26, p = 0.013 and HR = 3.59, p = 0.008, respectively). These findings suggest that NLR captures residual post-treatment inflammation and immune dysregulation beyond conventional blood counts, as confirmed by joint modeling, which more precisely links its longitudinal changes to thrombotic and mortality risk.

Thus, NLR may serve not only as a prognostic biomarker, but also as a dynamic surrogate of molecular and therapeutic response in PV—providing a more comprehensive, accessible and clinically actionable tool than ANC or total leukocyte count alone.

However, NLR must be interpreted within the clinical context, considering confounders like chronic inflammation, occult infections, or iron deficiency from phlebotomy. As a ratio, NLR has limitations, especially when both neutrophils and lymphocytes are affected by treatment or comorbidities; thus, absolute counts remain essential for accurate interpretation in both research and practice.

In addition, Ropeg’s selective neutrophil suppression with relative lymphocyte preservation reinforces its potential role as a potent anti-inflammatory therapy, distinct from HU. The greater and more durable effect on NLR suppression observed in PROUD-PV/CONTI-PV compared to Low-PV may be explained by differences in cohort characteristics or Ropeg doses between the two studies. The PROUD-PV/CONTI-PV [25] cohort enrolled patients with higher thrombotic risk PV compared to Low-PV patients [23, 24] and received Ropeg at doses escalated according to response, whereas Low-PV used a low fixed dose (cumulative 4-weekly median dose 499 µg vs. fixed 100 µg every two weeks in Low-PV).

A critical finding across these studies was that NLR reduction closely tracked with JAK2V617F VAF suppression, particularly in Ropeg-treated patients. Patients who experienced a greater than 50% NLR reduction also demonstrated a −59.3% decline in JAK2V617F VAF, whereas those with minimal NLR change exhibited only a −13.0% reduction. Interestingly, this activity was near identical for those treated on the Low-PV or PROUD/CONTI-PV studies with reduction in NLR closely mirroring reduction in JAK2V617F VAF. This suggests that NLR may serve as a surrogate marker for molecular response, reflecting suppression of the JAK2-mutant clone.

Additionally, NLR reduction was strongly associated with improved event-free survival (EFS), reinforcing its potential as a predictive biomarker rather than just an inflammatory marker.

This result needs to be interpreted with caution given the limited number of events and needs to be validated in larger, prospective cohorts.

In PROUD-PV/CONTINUATION-PV [25], patients with lower NLR over time had significantly reduced rates of thrombosis and progression to myelofibrosis, along with improved overall survival. This suggests that correction of this inflammatory biomarker with Ropeg may serve as a surrogate not only for JAK2V617F VAF suppression but also for event-free survival. This biomarker is widely available and inexpensive and could serve as a valuable surrogate for monitoring molecular response in routine clinical practice, particularly for therapies such as Ropeg that target both clonal hematopoiesis and inflammation.

Given its low cost and widespread availability, NLR may serve as a practical biomarker for tracking disease response and guiding therapeutic decision-making in PV.

Conclusion

This study highlights the distinct effects of HU and Ropeg on leukocyte-derived biomarkers in PV. While both reduce leukocytosis and neutrophilia -key thrombosis drivers- Ropeg also normalizes NLR, lowers JAK2V617F VAF, and better preserves lymphopoiesis, suggesting potential to reduce thrombosis and modify disease progression. These findings support NLR as a predictive biomarker, reinforcing the importance of inflammation-targeted strategies in PV management.

Data availability

Aggregated data available by request. Patient-level data will not be shared.

References

Barbui T, Carobbio A, Guglielmelli P, Ghirardi A, Fenili F, Loscocco GG, et al. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio identifies low-risk polycythaemia vera patients for early Ropeginterferon alfa-2b therapy. Br J Haematol. 2024;205:2287–94.

Tefferi A, Barbui T. Polycythemia vera: 2024 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023;98:1465–87.

Gerds AT, Gotlib J, Ali H, Bose P, Dunbar A, Elshoury A, et al. Myeloproliferative Neoplasms, Version 3.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:1033–62.

Marchetti M, Vannucchi AM, Griesshammer M, Harrison C, Koschmieder S, Gisslinger H, et al. Appropriate management of polycythaemia vera with cytoreductive drug therapy: European LeukemiaNet 2021 recommendations. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9:e301–e311.

Hasselbalch HC. Perspectives on chronic inflammation in essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis: is chronic inflammation a trigger and driver of clonal evolution and development of accelerated atherosclerosis and second cancer? Blood. 2012;119:3219–25.

Koschmieder S, Mughal TI, Hasselbalch HC, Barosi G, Valent P, Kiladjian J-J, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms and inflammation: whether to target the malignant clone or the inflammatory process or both. Leukemia. 2016;30:1018–24.

Moliterno AR, Kaizer H, Reeves BN. JAK2 V617F allele burden in polycythemia vera: burden of proof. Blood. 2023;141:1934–42.

Barbui T, Finazzi G, Falanga A. Myeloproliferative neoplasms and thrombosis. Blood. 2013;122:2176–84.

Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473:317–25.

Kristiansen MH, Kjær L, Skov V, Larsen MK, Ellervik C, Hasselbalch HC, et al. JAK2V617F mutation is highly prevalent in patients with ischemic stroke: a case-control study. Blood Adv. 2023;7:5825–34.

Wolach O, Sellar RS, Martinod K, Cherpokova D, McConkey M, Chappell RJ, et al. Increased neutrophil extracellular trap formation promotes thrombosis in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaan8292.

Shahneh F, Grill A, Klein M, Frauhammer F, Bopp T, Schäfer K, et al. Specialized regulatory T cells control venous blood clot resolution through SPARC. Blood. 2021;137:1517–26.

Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:519–31.

Kovacsovics-Bankowski M, Kelley TW, Efimova O, Kim SJ, Wilson A, Swierczek S, et al. Changes in peripheral blood lymphocytes in polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia patients treated with pegylated-interferon alpha and correlation with JAK2V617F allelic burden. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2015;5:28.

Choi DC, Messali N, Uda NR, Abu-Zeinah G, Kermani P, Yabut MM, et al. JAK2V617F impairs lymphoid differentiation in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia. 2024;38:2487–91.

Tefferi A, Loscocco GG, Farrukh F, Szuber N, Mannelli F, Pardanani A, et al. A globally applicable ‘triple A’ risk model for essential thrombocythemia based on Age, Absolute neutrophil count, and Absolute lymphocyte count. Am J Hematol. 2023;98:1829–37.

Krecak I, Lekovic D, Arsenovic I, Holik H, Zekanovic I, Moric Peric M, et al. The triple A model (age, absolute neutrophil count, absolute lymphocyte count-AAA) predicts survival and thrombosis in polycythemia vera. Am J Hematol. 2024;99:989–92.

Larsen MK, Skov V, Kjær L, Eickhardt-Dalbøge CS, Knudsen TA, Kristiansen MH, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and all-cause mortality with and without myeloproliferative neoplasms-a Danish longitudinal study. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14:28.

Nøst TH, Alcala K, Urbarova I, Byrne KS, Guida F, Sandanger TM, et al. Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36:841–8.

Carobbio A, Vannucchi AM, De Stefano V, Masciulli A, Guglielmelli P, Loscocco GG, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is a novel predictor of venous thrombosis in polycythemia vera. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:28.

Barbui T, Carobbio A, Ghirardi A, Fenili F, Finazzi MC, Castelli M, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic indicator of mortality in Polycythemia Vera: insights from a prospective cohort analysis. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14:195.

Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, Cacciola R, Cavazzina R, Cilloni D, et al. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N. Engl J Med. 2013;368:22–33.

Barbui T, Vannucchi AM, De Stefano V, Masciulli A, Carobbio A, Ferrari A, et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus phlebotomy in low-risk patients with polycythaemia vera (Low-PV study): a multicentre, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e175–e184.

Barbui T, Vannucchi AM, De Stefano V, Carobbio A, Ghirardi A, Carioli G, et al. Ropeginterferon versus standard therapy for low-risk patients with polycythemia vera. NEJM Evid. 2023;2:EVIDoa2200335.

Gisslinger H, Klade C, Georgiev P, Krochmalczyk D, Gercheva-Kyuchukova L, Egyed M, et al. Ropeginterferon alfa-2b versus standard therapy for polycythaemia vera (PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV): a randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial and its extension study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e196–e208.

Torres LS, Hidalgo A. Neutrophils as drivers of vascular injury in sickle cell disease. Immunol Rev. 2023;314:302–12.

Maharaj S, Chang S. Clinical utility of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in sickle cell disease with vaso-occlusive crisis. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2023;16:79–82.

Zahran AM, Nafady A, Saad K, Hetta HF, Abdallah A-EM, Abdel-Aziz SM, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea treatment on the inflammatory markers among children with sickle cell disease. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26:1076029619895111.

Sanchez C, Le Treut T, Baier C, Sébahoun G, Costello RT. Distribution of lymphocyte subpopulations in patients with polycythemia vera. Hum Immunol. 2015;76:414–6.

Veletic I, Prijic S, Manshouri T, Nogueras-Gonzalez GM, Verstovsek S, Estrov Z. Altered T-cell subset repertoire affects treatment outcome of patients with myelofibrosis. Haematologica. 2021;106:2384–96.

Vannucchi AM, Masala G, Antonioli E, Chiara Susini M, Guglielmelli P, Pieri L, et al. Increased risk of lymphoid neoplasms in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2009;18:2068–73.

Acknowledgements

The ECLAP, LOW-PV and PROUD-PV Study investigators, patients and collected clinical data.

Funding

This work is part of the RICO project (Ricerca Istituzionale Collaborativa-Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII di Bergamo) supported by “Bottega del Riuso di Mano in Mano” (Caritas Parrocchiale di Clusone), Italy; it is sponsored by FROM-Fondazione per la Ricerca Ospedale di Bergamo-ETS. The PROUD/CONTINUATION-PV studies were sponsored by AOP Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TB conceived and designed the study, supervised the analysis, and wrote the paper. AG performed statistical analyses and contributed to paper writing. FF directed the project and collected the data. GGL, AC, AI, DC, ER, VDS, PG, AR, JMS, AMV, CK and HG revised the study and contributed to paper writing. VE supervised analyses and contributed to paper writing. The manuscript was approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TB: Research grant from GSK and AOP. Advisory Board AOP and Italfarmaco. VE and CK are employees of AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals. GGL: Speaker’s bureau from Novartis and GSK. AI: Speaker honoraria from AOP Health, BMS, GSK, Incyte, Novartis and Pfizer. ER: Advisory Board AOP Health. VDS: Advisory Board AOP Health. PG: Advisory Board Novartis, Incyte and GSK; Speaker’s bureau for Novartis, Gsk, Abbvie, AOP. AMV: Advisory Board and/or lectures from Novartis, AbbVie, AOP Pharmaceuticals, BMS and Incyte. HG: grants and/or personal fees from AOP Health, Novartis, and BMS-Pharma. AR: fees for consultancies and participation in meetings, boards, and symposia sponsored by Amgen, Pfizer, Novartis, Kite‐Gilead, Jazz, Astellas, Abbvie, Incyte, and Omeros. JMS: Advisory Board or Consultant for Abbvie, Incyte, Protagonist, Novartis, SDP Oncology and Karyopharm. AG, FF, AC and DC have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barbui, T., Ghirardi, A., Empson, V. et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio as surrogate for JAK2V617F suppression and event-free survival in polycythemia vera. Blood Cancer J. 15, 132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01317-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01317-6

This article is cited by

-

Shifting treatment goals in myeloproliferative neoplasms: focusing on polycythemia vera

International Journal of Hematology (2025)

-

Results from a US modified Delphi consensus to define disease progression and disease modification in polycythemia Vera

Annals of Hematology (2025)