Abstract

PET after 2 ABVD cycles (PET-2) is widely adopted to select patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), who might benefit from intensifying or de-escalating therapy. Prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) has been reported in PET-2 positive patients switched to escalated BEACOPP (eBEACOPP) or BEACOPP-14. Nevertheless, the subgroup of patients with a PET-2 scored 5 according to Deauville score (PET-2 DS5) are known to poorly benefit from treatment intensification. To elucidate PET-2 DS5 outcome along with possible predictive factors of response to intensification, a pooled analysis from three multicenter trials, GITIL/FIL HD0607, RATHL, and SWOG S0816, was conducted. PFS and overall survival (OS) were assessed after 41-month median follow-up, the prognostic value of clinical, laboratory, and PET parameters at diagnosis was evaluated. Among 2231 patients, 136 (6%) PET-2 DS5 patients were identified. Their 3-year PFS was 32% (95% CI, 25–42), while the 3-year OS was 82% (95% CI, 75–89). In multivariate analysis low lymphocyte (< 600/mm3) counts were adversely associated with PFS, whereas age ≥ 45 years and leukocytes cells count <15 × 103/μL were barely associated with short OS. The study confirms on a suitable cohort of PET-2 DS5 patients, that this high-risk cHL subgroup has an inadequate response to treatment intensification. Nevertheless, PET-2 DS5 patients may still have good outcome after subsequent salvage treatments with > 80% survival at 3 years, thus excluding a real disease refractoriness. Few distinct parameters may have specific prediction for PFS or OS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Early-interim positron emission tomography/computerized tomography (PET/CT) scan, performed after the first two cycles of chemotherapy (PET-2), is nowadays widely accepted as a prognostic tool in advanced stage (AS) classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), thus confirming the role of an early chemosensitivity assessment as surrogate of the final treatment outcome. Several prospective trials have confirmed that a response–adapted approach, using PET-2 to select patients who might benefit from intensifying or de-escalating therapy, is safe and results in improved progression-free survival (PFS) or reduced toxicity compared to results obtained in historical controls with six cycles of ABVD (doxorubicin hydrochloride [Adriamycin], bleomycin sulfate, vinblastine sulfate, dacarbazine) or six to eight cycles of escalated BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin hydrochloride [Adriamycin], cyclophosphamide, vincristine [Oncovin], procarbazine, prednisone) (eBEACOPP) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

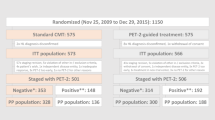

PET positivity after the first two cycles of ABVD (PET-2+), defined as a score of 4 or 5 on the five-point Deauville scale (DS) [13, 14], is highly predictive for refractory outcomes when continuing with ABVD [15]. The early treatment intensification with eBEACOPP, as tested in the RATHL, SWOG S0816, and GITIL/FIL HD0607 trials, proved able to overcome the ABVD chemoresistance in PET-2 positive patients, resulting in PFS of 60% to 67.5% at 2 or 3 years [5, 6, 8].

Patients with PET-2 DS 5 represented no more than 3%–6% of the entire patient population enrolled in these trials and, due to small numbers, to date no clinical characteristic nor biological marker predictive of response has been identified.

To define the overall outcome and identify possible predictive markers in this patient subset, we performed a pooled analysis of individual patient data of the three multicenter studies, RATHL, SWOG S0816, and GITIL/FIL HD0607, focusing on patients with PET-2 DS 5 who had intensified treatment with eBEACOPP or BEACOPP-14 after two ABVD courses. The primary aim of the study was to define both PFS following treatment intensification and the overall life expectancy of this cohort of high-risk patients. Moreover, we retrospectively evaluated new and old predictive/prognostic factors recorded at baseline, in order to identify possible clinical and laboratory characteristics able to early predict response to salvage treatment and the overall long-term outcome in this small patient subset.

Patients and methods

Patients

Individual patient data from the databases of three multicenter trials, GITIL/FIL HD0607 (n = 782), RATHL (n = 1203), and SWOG S0816 trial (n = 336), evaluating PET-adapted treatment in AS cHL, were analysed. All PET-2 DS 5 patients were included in this study: 58 patients from RATHL, 29 patients from SWOG and 49 patients from HD0607 trials. Patient demographics along with the classic prognostic factors at baseline (i.e., date of birth, sex, date of diagnosis, stage, IPS, bulky disease, number of involved nodal and extranodal sites, leukocyte, lymphocyte, neutrophil, monocyte counts, hemoglobin values) were collected. Among new prognostic factors total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) and Total lesion glycolysis (TLG) were assessed. Furthermore, date of diagnosis, date of ABVD start, date of PET-2- DS 5, date of treatment intensification (eBEACOPP(BEACOPP-14) start, date and results of PET-3 according to DS, date of therapy change (if any), information on subsequent therapies, date of ASCT(s) and allo-SCT(if performed), date of CMR achievement, based on the Lugano 2014 criteria [16], date of progression or relapse, date and cause of death, date and type of second malignancy (if any), date of last follow-up and status at last FU were collected.

Treatment

In the three studies, patients received 2 cycles of ABVD followed by early-interim PET scan (PET-2). In the RATHL trial, PET-2+ patients received either three cycles of eBEACOPP or four cycles of BEACOPP-14, chosen in advance by each treatment center. Thereafter, patients were reassessed with a third PET-CT scan (PET-3) and patients with a negative PET-3 received one more cycle of eBEACOPP or two further cycles of BEACOPP-14. Patients with a positive PET-3 underwent further salvage treatment in accordance with local protocols [5].

In SWOG S0816, PET-2+ patients received 6 cycles of eBEACOPP [7].

In GITIL/FIL HD0607, 4-eBEACOPP plus 4-BEACOPP baseline with or without Rituximab were administered to PET-2+ patients [10].

All patients provided written, informed consent before enrolment in each study. Data use agreements were made between the RATHL Network, the SWOG Cancer Research Network, the HD0607 Network and investigators at the European Institute of Oncology; the study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the participating centers and was done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

PET imaging and calculation of TMTV

PET/CT scans at diagnosis and after two ABVD cycles were acquired on accredited scanners in all the three trials as previously described [5, 7, 10]. All PET/CT scans were centrally reviewed during these trials. The scans of the RATHL trial were preliminary reviewed because the cutoff value used to distinguish a score 4 from a score 5 was different in the original RATHL publication compared to SWOG S0816 and HD0607: in the former the cutoff value was set to 300% of the standardized maximum liver uptake value (SUVMax) while in the two latter studies the threshold was set to 200% of the liver SUVMax. For the purpose of the present study DS 5 was assigned to lesions having uptake at least twofold higher than the maximum liver uptake and/or the appearance of new lesions compatible with lymphoma. For the RATHL and HD0607 trials the data were analysed also according to the definition of DS 5 scored more than threefold the maximum liver uptake and/or the appearance of new lesions. For this project, three nuclear medicine physician(s) (SB, SH, LG) additionally reviewed the scans, blinded to patient history, clinical data, and treatment outcome, identifying the location of the most active lesion in PET-2 (reference lesion) that was visually scored according to DS as described elsewhere [13].

TMTV was segmented on PET/CT images using a fixed standardized uptake value of 4.0 using the recently published benchmark method [17]. First, automated segmentation was performed using the software, then, if necessary, manual addition of lesions and editing to subtract physiological uptake was undertaken.

Only focal extranodal and splenic lesions were included in the volume of interest, whereas diffuse increase in 18F-FDG uptake in the spleen and/or bone marrow was excluded. The TMTV was obtained by summing the metabolic volumes of all nodal and extranodal lesions. TLG was calculated as the product of TMTV and average SUV in the contoured lesions.

Study objectives

The primary objectives were to evaluate PFS and OS in AS cHL patients with a PET-2 DS 5 in a pooled database analysis of all three multicenter studies, comparing patients who progressed (non-responders) after intensified treatment with eBEACOPP or BEACOPP-14, with those who did not progress or relapse (responders). Secondary objectives were to retrospectively evaluate potential predictors of treatment outcome, including patient characteristics, histology, disease extent, international prognostic score, laboratory parameters, PET TMTV and TLG, at diagnosis, comparing non-responders to responders.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used. Differences in categorical parameters were evaluated using chi-squared of Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Differences in continuous parameters were evaluated using Mann–Whitney U test. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analyses were performed to evaluate the prognostic value of TMTV and TLG. The analysis of differences in TMTV and TLG among the three trials were evaluated by Wilcoxon pairwise comparisons.

PFS was measured from the date of PET-2 until the date of disease progression, disease relapse after CR, or lack of CR at the end of per protocol therapy, or death from any cause. If none of these events occurred, patients were censored at the date of information on HL status at last follow-up.

Duration of CR (DCR) was measured from the date of CR or CMR achievement to the date of disease progression, relapse, or death from any cause. If none of these events occurred, DCR was calculated as the date of information on HL-free status at last follow-up.

OS was measured from the date of PET-2 until the date of death of any cause. Patients alive were censored based on the date of last information on survival status.

Survival outcomes were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. The association between factors with PFS or OS events was evaluated using univariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailored P value of 0.05. All analyses were performed with R software, version 4.3.0.

Results

From 2321 patients recruited in the three trials with available baseline and PET-2 scans, 136 patients (6%) with PET-2 DS 5 were included in this study.

Patient demographics and characteristics, laboratory parameters, TMTV, and TLG values at diagnosis are detailed in Table 1.

Since the SWOG trial only recruited patients with stage III or IV, whereas RATHL and HD0607 trials included also stage II with adverse features, the following differences in patient characteristics emerged among the trials: stage III and IPS > 3 were significantly more frequent by study design, median hemoglobin level was lower and TMTV and TLG values were higher in the patients enrolled on the SWOG S0816 trial compared to RATHL and HD0607 subgroups. B symptoms were more frequently reported in patients enrolled on the HD0607 trial.

Overall, 56 out of 136 PET-2 DS 5 patients (41.2%) achieved a metabolic complete remission (CMR) with a negative PET at the end of treatment intensification (EOT-PET) with eBEACOPP or BEACOPP-14, 32 patients had partial remission (23.5%), 5 patients (3.7%) had stable disease, 31 (22.8%) progressed. One toxic death, due to septic shock following Klebsiella pneumoniae, occurred. Data of response to intensified treatment were not available in 7 patients (5.1%) and 4 patients (2.9%) were withdrawn after PET-2 and did not receive intensified treatment due to patient or principal investigator decisions.

As shown in Fig. 1A, B, after a median follow-up of 41 months (range, 1–36), the 3-year PFS and OS were 32% (95%CI, 25–42) and 82% (95%CI, 75–89), respectively. The 3-year PFS and OS analysed in 106 patients of the RATHL and HD0607 trials according to the definition of DS 5 scored >300% the maximum liver uptake, were 31% and 79%, respectively, without significant differences compared to DS 5 scored 200–300% of the liver, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1A, B. Most patients (96%) who achieved a CR and did not relapse within 2 years, had a prolonged PFS (Supplementary Fig. 2). The 3-year DCR for intensified treatment was 70% (95% CI, 58–84) (Fig. 2). Patients who achieved CR with intensified treatment (n = 56) had a longer 3-year OS compared to those not in CR (n = 69) (91% vs 74%, P = 0.0073) (Fig. 3). No factor at baseline was associated with the probability of achieving CR after intensified treatment as shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Patients progressing after BEACOPP-like intensification regimens were not homogeneously treated and missing data for most patients prevented a detail description of salvage treatments received.

Overall, in 136 PET-2 DS 5 patients, seven second malignancies occurred, after a median of 34 months (range, 11–61) from the date of PET-2: one medullary thyroid carcinoma, one kidney carcinoma, one melanoma, one nasopharyngeal carcinoma, one non-small cell lung cancer, one anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and one acute lymphoblastic leukemia. All second cancers were reported in patients who achieved CR after intensified treatment; six patients were alive after a median of 28 months (range, 0–85) from the diagnosis of second cancer, while one patient died 10 months after the diagnosis of ALCL.

As detailed in Table 2, in univariate analysis low lymphocyte count (<600/μL) was significantly associated with poor PFS (<600/μL vs ≥ 600/μL: HR 3.19; P = 0.0007) as well as absence of marked leukocytosis (<15 × 103/μL vs ≥ 15 × 103/μL: HR 0.63; P = 0.0385). On the other hand, age ≥ 45 years, leukocyte cells count <15 × 103/μL, and low monocyte (<0.5 × 103/μL) counts significantly shortened OS. As shown in Table 3, in multivariable analysis low lymphocyte count was an independent negative prognostic factor for PFS, whereas age ≥ 45 years and leukocyte cells count <15 × 103/μL adversely affected OS.

Overall, the median TMTV4 at baseline was 243 cm3 (range, 1.6–4266) and baseline median TLG 4 was 1476 cm3 (range, 7.3–29386) for the whole patient population. However, a significant difference in these values emerged among the three trials, as shown in Supplementary Table 3, with higher TMTV and TLG values in patients included in the SWOG trial, who had more advanced disease (stage III or IV). The ROC curve analysis of the prognostic performance of TMTV 4 and TLG for 3-year PFS showed an AUC of 0.41 and 0.40, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we report survival outcomes for 136 out of 2231 (6%) patients with AS cHL enrolled in three multicenter studies, RATHL, SWOG S0816, and GITIL/FIL HD0607 GITIL/FIL, who had a positive PET DS 5 after two ABVD cycles. The results of the pooled analysis confirm the unsatisfactory response of these patients to intensified treatment with eBEACOPP or BEACOPP-14, with a 3-year PFS of 32% (95% CI, 25–42). Nevertheless, the 3-year OS was 82% (95% CI, 75–89), due to effective further salvage treatments.

In univariate analysis, low lymphocyte count (<600/μL) and leukocyte cells count <15 × 103/μL measured at diagnosis were able to detect refractory outcomes to intensification therapy whereas age ≥ 45 years and leukocyte cells count <15 × 103/μL were significantly associated with short OS. The unfavorable prognostic value of leukocyte cells count <15 × 103/μL is an unexpected finding. However, it is confirmed for OS at the multivariable analysis and seems a peculiar feature for this cHL subset.

PET-2 DS 5 patients behave quite similarly to patients with primary refractory disease, defined as progression or non-response during induction treatment or within 90 days of completing treatment. Indeed, PET-2 DS 5 patients have a high likelihood of a PFS event, and they frequently require several subsequent therapies, including autologous stem cell transplantation or even allogeneic transplantation. The long-term iatrogenic effects in survivors, in particular therapy-related myelodysplastic syndromes or acute leukemias and solid second malignancies are well documented [18].

Early interim PET demonstrated prognostic relevance in all trials that have tested PET-adapted treatment strategies in AS HL [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. The assessment of TMTV measured on baseline PET scans has been shown to be an independent prognostic factor in a post-hoc analysis of the EORTC H10 trial in early-stage HL: 5-year PFS was 71% in the high-TMTV (>147 cm3) group vs 92% in the low-TMTV group (≤147 cm3) segmented using a threshold of 41% of the maximum SUV [19]. Furthermore, in a retrospective study on 115 patients with stage IIB, III, and IV HL treated with ABVD, TMTV was predictive of overall 5-year PFS (p = 0.0079) with an HR of 2.29 but only in the subgroup of patients who received ABVD and not in the group who received eBEACOPP [20]. Among 65 transplant-eligible patients with relapsed/refractory HL, baseline MTV and refractory disease predicted outcome, with 3-year PFS of 100% in patients with low MTV (<109.5 cm3) and relapsed disease [21]. However, the results of our study show that baseline PET parameters of TMTV and TLG did not provide additional predictive value in patients with a positive PET DS 5 after two cycles of ABVD chemotherapy who have inferior outcomes even after intensified conventional chemotherapy with BEACOPP-based regimens, and who still represent an unmet clinical need.

New biomarkers at diagnosis are warranted to better prognosticate outcome and personalize treatment for this cohort of patients. The evaluation of the difference between baseline and PET-2 TMTV/TLG, or the combination of TMTV assessment with other sensitive biomarkers, such as circulating tumor DNA [22], so called liquid biopsy, serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine levels [23], Epstein-Barr viral whole blood or plasma load [24], small micro-RNA (miRs) contained in extracellular vesicles [25], should be evaluated to improve the accuracy of identification of those low-risk PET-2 DS 5 patients for whom escalating therapy with eBEACOPP is safe.

We are aware that our study has some limitations, the most relevant of which was the inhability to evaluate gene expression profiling of biopsies at diagnosis of PET-2 DS 5 cohort, as well as the lack of PET-2 TMTV and TLG evaluation, which both could refine the ability to be predict response to intensification to BEACOPP-based schedules.

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of PET-2 DS 5 patients reported so far. The results of our study, evaluating data from three large randomized international trials, may contribute to increase our insight on characteristics, risk factors and outcome of the cohort of patients with an interim PET scored DS 5 after 2 ABVD cycles.

Patients progressing after BEACOPP-like treatment intensification underwent one or more lines of multiple salvage therapies, ranging from intensified chemotherapy with or without autograft, allogeneic hematopoietic transplantation, brentuximab vedotin, anti-PD1 monoclonal antibodies. The high heterogeneity along with missing data for most patients prevent to analyze in detail all salvage treatments delivered. However, we can speculate that the remarkable high OS rate may be related to the use of new drugs in the salvage setting that became available in recent years.

The landscape of first-line and salvage treatment for AS and relapsed or refractory cHL has changed with the availability of effective new drugs, such as anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin (BV) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), nivolumab, and pembrolizumab. In the Echelon-1 trial, treatment of stage III-IV cHL with the combination of doxorubicin, vinblastine, dacarbazine, and brentuximab vedotin (A-AVD) yielded superior results compared to ABVD in terms of 6-year modified PFS (82.3% vs 74.5%) and OS (93.9% vs 89.4%) [26]. Although the majority (89%) of patients treated with A-AVD had a negative PET-2, patients with a positive PET-2 had a 6-year PFS of 61%. PET-2 positive patients in this trial were not escalated to eBEACOPP, although those with a PET-2 DS 5 could switch to alternative therapy at the treating physician’s discretion.

The BrECADD regimen, developed by the GHSG with the addition of BV, to the backbone of doxorubicin, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide, omitting vincristine/bleomycin, replacing procarbazine with dacarbazine, and substituting prednisone with a short course of dexamethasone, has shown improved efficacy and tolerability when compared to eBEACOPP, as reported in 1482 AS cHL patients aged 18–60 years [11]. At 4 years, OS was superimposable for the two treatment groups (98.6% vs 98.2%), with higher PFS 94.3% vs 90.9% (HR 0.66, 95% CI, 0.45–0.97; p = 0.035), even in PET-2 positive patients (90.3% vs 87.8%). Furthermore, treatment-related morbidity was significantly lower and gonadal function recovery was more common with BrECADD compared to eBEACOPP.

The SWOG S1826 trial randomly comparing AVD (doxorubicin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) in combination with Nivolumab (N-AVD) with A-AVD in patients with stage III or IV cHL, aged 12 years or older, showed superior 2-year PFS with N-AVD (92% vs 83%; HR 0.45; 95%CI, 030–0.65; P < 0.001), with superimposable OS (99% vs 98%) and numerically fewer deaths (7 vs 14), albeit with a short median follow-up of 2.1 years months but this study was not PET-adapted [27]. Lynch et al. documented in a small single-arm study of concurrent pembrolizumab with AVD (doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; APVD) a 2-year PFS of 97% and OS of 100% in 30 untreated cHL patients, despite a negative PET-2 rate of only 57%, probably due to an unspecific FDG uptake due to a restored immunity of the patients [28]. Other studies evaluating PET responses after single agent checkpoint blockade in patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin lymphoma failed to demonstrate the utility of PET as a robust biomarker in this situation [29, 30].

Transient immunologic flares with increase in FDG-uptake, which can resemble disease progressions, have been reported after treatment with ICIs and new response criteria, for which the so-called Lymphoma Response to Immunomodulatory Therapy Criteria were developed [31].

The recently updated NCCN guidelines still recommend, in patients with AS cHL for whom BV or ICIs are not available or contraindicated, a PET-adapted strategy with ABVD as the preferred initial treatment with the shift to BrECADD in PET-2+ patients [32]. Given the low PFS rates reported with chemotherapy only approaches, such as eBEACOPP or BEACOPP-14, the shift to BrECADD or the addition of ICIs to conventional chemotherapy, if not introduced in the front-line treatment, should be a future focus for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and DS5 on PET-2.

Future studies should incorporate novel methodologies like this for review of imaging studies in Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as explore novel parameters on PET imaging, including metabolic tumor volume and disease dissemination, rather than only Deauville scores [33,34,35].

The efficacy of PD-1 blockade, if not introduced in front-line treatment, should be explored in the early salvage treatment of PET-2 DS 5 patients. Given the low PFS rates reported with intensified chemotherapy approaches, such as eBEACOPP or BEACOPP-14, and the lack of clear-cut baseline prognostic factors that add to the predictive value of interim PET, the addition of ICIs to conventional chemotherapy should be a future focus for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma and DS5 on PET-2.

Conclusion

cHL patients with PET-2 DS 5 after ABVD have similar outcomes to patients with refractory disease, with only 32% PFS at 3 years. Low lymphocyte count measured at diagnosis is the only parameter able to detect the later failures within the DS 5 cohort in three large phase III randomized controlled trials. Nevertheless, patients with DS-5 PET-2 can benefit from a prolonged OS, albeit at the cost of multiple subsequent treatments, including autologous and eventually allogeneic transplant. Based on the excellent results in relapsed or refractory cHL with new agents, brentuximab vedotin and PD-1 inhibitors-containing salvage regimens, the early introduction when DS 5 at PET-2 is documented, should be evaluated to improve the cure rate while sparing additional chemotherapeutic treatments, known to have low therapeutic efficacy along with long-term toxicity.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Hutchings M, Loft A, Hansen M, Pedersen LM, Buhl T, Jurlander J, et al. FDG-PET after two cycles of chemotherapy predicts treatment failure and progression-free survival in Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 107:52–9. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2005-06-2252.

Gallamini A, Rigacci L, Merli F, Nassi L, Bosi A, Capodanno I, et al. The predictive value of positron emission tomography scanning performed after two courses of standard therapy on treatment outcome in advanced stage Hodgkin’s disease. Haematologica. 2006;91:475–81.

Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, Meignan M, Hutchings M, Müeller SP, et al. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the international conference on malignant lymphomas imaging working group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3048–58. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5229.

Engert A, Haverkamp H, Kobe C, Markova J, Renner C, Ho A, et al. Reduced-intensity chemotherapy and PET-guided radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HD15 trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1791–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61940-5.

Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood A, Fosså A, Berkahn L, Carella A, et al. Adapted treatment guided by interim PET-CT scan in advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2419–29. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1510093.

Luminari S, Fossa A, Trotman J, Molin D, d’Amore F, Enblad G, et al. Long-Term follow-up of the response-adjusted therapy for advanced Hodgkin lymphoma trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:13–18. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.01177.

Press OW, Li H, Schöder H, Moskowitz CH, LeBlanc M, Rimsza LM, et al. US intergroup trial of response-adapted therapy for stage III to IV Hodgkin lymphoma using early interim fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography imaging: southwest oncology group S0816. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2020–27.

Stephens DM, Li H, Schöder H, Straus DJ, Moskowitz CH, LeBlanc M, et al. Five-year follow-up of SWOG S0816: limitations and values of a PET-adapted approach with stage III/IV Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2019;134:1238–46. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000719.

Zinzani PL, Broccoli A, Gioia DM, Castagnoli A, Ciccone G, Evangelista A, et al. Interim positron emission tomography response-adapted therapy in advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma: final results of the phase II part of the HD0801 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1376–85. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0699.

Gallamini A, Tarella C, Viviani S, Rossi A, Patti C, Mulé A, et al. Early chemotherapy intensification with escalated BEACOPP in patients with advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma with a positive interim positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan after two ABVD cycles: long-term results of the GITIL/FIL HD 0607 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:454–62. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.75.2543.

Borchmann P, Haverkamp H, Lohri A, Mey U, Kreissl S, Greil R, et al. Progression-free survival of early interim PET-positive patients with advanced stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with BEACOPPescalated alone or in combination with rituximab (HD18): an open-label, international, randomised phase 3 study by the German Hodgkin Study Group. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:454–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30103-1.

Casasnovas RO, Bouabdallah R, Brice P, Lazarovici J, Ghesquieres H, Stamatoullas A, et al. Positron emission tomography-driven strategy in advanced Hodgkin lymphoma: prolonged follow-up of the AHL2011 phase III lymphoma study association study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:1091–101. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.01777.

Meignan M, Gallamini A, Haioun C. Report on the first international workshop on interim-PET-scan in lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:1257–60.

Gallamini A, Barrington SF, Biggi A, Chauvie S, Kostakoglu L, Gregianin M, et al. The predictive role of interim positron emission tomography on Hodgkin lymphoma treatment outcome is confirmed using the 5-point scale interpretation criteria. Haematologica. 2014;99:1107–13. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2013.103218.

Gallamini A, Hutchings M, Rigacci L, Specht L, Merli F, Hansen M, et al. Early interim 2-[18F]Fluoro-2-Deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography is prognostically superior to international prognostic score in advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a report from a joint Italian-Danish study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3746–52. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6525.

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington S, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, et al. Recommendations for Initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3059–68.

Boellaard R, Buvat I, Nioche C, Ceriani L, Cottereau AS, Guerra L, et al. International benchmark for total metabolic tumor volume measurement in baseline 18F-FDG PET/CT of lymphoma patients: a milestone toward clinical implementation. J Nucl Med. 2024;65:1343–8. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.124.267789.

Socie G, Baker KS, Bhatia S. Subsequent malignant neoplasms after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2012;18:S139–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.005.

Cottereau AS, Versari A, Loft A, Casasnovas O, Bellei M, Ricci R, et al. Prognostic value of baseline metabolic tumor volume in early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma in the standard arm of the H10 trial. Blood. 2018;131:1456–63. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-07-795476.

Pinochet P, Texte E, Stamatoullas-Bastrad A, Vera P, Mihailescu SD, Becker S. Prognostic value of baseline metabolic tumour volume in advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Sci Rep. 2021;11:23195. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02734-w.

Moskowitz AJ, Schöder H, Gavane S, Thoren KL, Fleisher M, Yahalom J, et al. Prognostic significance of baseline metabolic tumor volume in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2017;130:2196–203. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-06-788877.

Spina V, Bruscaggin A, Cuccaro A, Martini M, Di Trani M, Forestieri G, et al. Circulating tumor DNA reveals genetics, clonal evolution, and residual disease in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2018;131:2413–25. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-11-812073.

Viviani S, Mazzocchi A, Pavoni C, Taverna F, Rossi A, Patti C, et al. Early serum TARC reduction predicts prognosis in advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma patients treated with a PET-adapted strategy. Hematol Oncol. 2020;38:501–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2775.

Park JH, Yoon DH, Kim S, Park JS, Park CS, Sung H, et al. Pretreatment whole blood Epstein-Barr virus-DNA is a significant prognostic marker in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:801–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-016-2610-5.

Drees EEE, Driessen J, Zwezerijnen GJC, Verkuijlen SAWM, Eertink JJ, van Eijndhoven MAJ, et al. Blood-circulating EV-miRNAs, serum TARC, and quantitative FDG-PET features in classical Hodgkin lymphoma. EJHaem. 2022;3:908–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/jha2.432.

Ansell SM, Radford J, Connors JM, Długosz-Danecka M, Kim WS, Gallamini A, et al. Overall survival with brentuximab vedotin in stage III or IV Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:310–20.

Herrera AF, LeBlanc M, Castellino SM, Li H, Rutherford SC, Evens AM, et al. Nivolumab+AVD in advanced-stage classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1379–89. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2405888.

Lynch RC, Ujjani CS, Poh C, Warren EH, Smith SD, Shadman M, et al. Concurrent pembrolizumab with AVD for untreated classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2023;141:2576–86. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022019254.

Allen PB, Lu X, Chen Q, O’Shea K, Chmiel JS, Slonim LB, et al. Sequential pembrolizumab and AVD are highly effective at any PD-L1 expression level in untreated Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2023;7:2670–6. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008116.

Voltin CA, Mettler J, van Heek L, Goergen H, Müller H, Baues C, et al. Early Response to first-line anti-PD-1 treatment in Hodgkin lymphoma: a PET-based analysis from the prospective, randomized phase II NIVAHL trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:402–7. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3303.

Cheson BD, Ansell S, Schwartz L, Gordon LI, Advani R, Jacene HA, et al. Refinement of the Lugano Classification lymphoma response criteria in the era of immunomodulatory therapy. Blood. 2016;128:2489–96. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-05-718528.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Hodgkin lymphoma (Version 2.2025). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hodgkins.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2025

Jemaa S, Ounadjela S, Wang X, El-Galaly TC, Kostakoglu L, Knapp A, et al. Automated Lugano metabolic response assessment in 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-avid non-Hodgkin lymphoma with deep learning on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:2966–77. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.01978.

Durmo R, Donati B, Rebaud L, Cottereau AS, Ruffini A, Nizzoli ME, et al. Prognostic value of lesion dissemination in doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine-treated, interimPET-negative classical Hodgkin Lymphoma patients: a radio-genomic study. Hematol Oncol. 2022;40:645–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.3025.

Tutino F, Giovannini E, Chiola S, Giovacchini G, Ciarmiello A. Assessment of response to immunotherapy in patients with hodgkin lymphoma: towards quantifying changes in tumor burden using FDG-PET/CT. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3498. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12103498.

Acknowledgements

This study was presented in part during the 12th International Symposium on Hodgkin Lymphoma (ISHL12), October 22–24, 2022.

Funding

NIH/NCI grant awards U10CA180888 and UG1CA233230; CT was partially supported by a grant from Piaggio S.p.A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SV and CT conceived the study. SV, CP, AAK, and DMS performed data extraction. CP performed statistical analysis. SFB, LG, HS, SC, MVK performed PET review. All authors (SV, CP, SFB, LG, HS, PJ, AAK, DMS, JWF, SC, MVK, SL, DM, PC, AG, AR, and CT) analyzed and interpreted the study data. All authors (SV, CP, SFB, LG, HS, PJ, AAK, DMS, JWF, SC, MVK, SL, DM, PC, AG, AR, and CT) edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committees of the participating centers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Viviani, S., Pavoni, C., Barrington, S.F. et al. Advanced stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma patients with a positive interim-PET (PET-2) Deauville score 5 after 2 ABVD cycles: a pooled analysis of three multicenter trials. Blood Cancer J. 15, 165 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01364-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01364-z