Abstract

Renal impairment (RI) is a serious complication in multiple myeloma (MM), linked to poor survival and early mortality. Rapid renal recovery improves outcomes, yet patients with RI have been excluded from most key trials in transplant-eligible newly diagnosed (TE-ND) MM. REMNANT is an ongoing, academic, multicenter phase 2/3 study in TE-NDMM patients aged 18–75, regardless of baseline renal function. Here, we report a subanalysis of the non-randomized phase 2 component. All patients received four 21-day cycles of induction with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone. Lenalidomide was dosed higher than the recommended standard of care: 25 mg/day for eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m² and 15 mg/day for eGFR <30. Between August 2020 and September 2024, 382 patients were enrolled; 81 (21%) had RI, including seven (2%) on dialysis during cycle 1. Renal response was achieved in 77%, with complete renal response in 57%. Five dialysis-dependent patients became dialysis-independent. Overall response rates were similar, and adverse events were comparable between RI and non-RI groups, except for higher rates of anemia and thrombocytopenia in the RI cohort. Four RI patients (5%) experienced worsening renal function; two cases were possibly related to lenalidomide, both reversible. These findings support the safety and efficacy of increased lenalidomide-dosing during induction in TE-NDMM patients with RI, including those with severe impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal impairment (RI) is a myeloma-defining event within the CRAB criteria [1], and a well-recognized adverse prognostic factor [2]. Even after adjusting for relevant cofactors and comorbidities, RI significantly reduces overall survival (OS) [3,4,5]. Real-world data confirms that acute kidney injury at diagnosis is particularly unfavorable, with the highest excess mortality occurring in the first six months of therapy [4, 6]. Rapid renal recovery is therefore a critical treatment goal, as it is consistently associated with improved clinical outcomes [6, 7]. Achieving a serum-free light chain (FLC) level <500 mg/L early in therapy is the most important determinant of such recovery [8, 9].

For transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (TE-NDMM) patients, lenalidomide-based induction regimens are the current standard of care [10]. The approved schedule for induction is lenalidomide at 25 mg/day on days 1–14 of a 21-day cycle or 25 mg/day on days 1–21 of a 28-day cycle. Because lenalidomide is primarily renally excreted, with minimal hepatic metabolism, current prescribing information recommends dose reductions in patients with glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 50 mL/min/1.73m2: 10 mg/day for moderate RI (eGFR 30-49 mL/min/1.73m2), 7.5 mg/day for severe RI (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2, not requiring dialysis) and 5 mg/day for dialysis-dependent patients [3, 11]. These adjustments are based on the pharmacokinetic study by Chen et al. [12], in which a single 25 mg dose of lenalidomide in 30 non-myeloma RI patients demonstrated increased systemic exposure with worsening renal function.

However, a previous clinical trial from the Mayo Clinic challenged the necessity of such conservative dosing. In the prospective phase 1/2 PrE1003 trial of lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory MM, full-dose lenalidomide (25 mg/day) was well tolerated in patients with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73m2 and 15 mg/day was tolerated even in patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2, including those receiving dialysis [13]. These findings raise the possibility that higher-than-label doses could be safely used in NDMM patients with RI, potentially facilitating faster serum-FLC reduction and renal recovery.

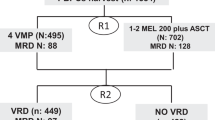

The REMNANT study [14] is an ongoing academic, multicenter, open-label phase 2/3 trial in TE-NDMM patients. It is designed to evaluate whether treating measurable residual disease (MRD) relapse after first-line therapy prolongs progression-free survival (PFS) and OS in patients with MM. In the non-randomized phase 2 component, TE-NDMM patients received induction therapy with bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone (VRd). After induction, patients underwent single or tandem autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) with high-dose melphalan, followed by VRd consolidation and lenalidomide maintenance. This phase serves as a feeder for the subsequent randomized phase 3 trial, which enrolls patients who achieve MRD-negative complete response (CR) following first-line treatment.

Within this non-randomized phase 2 component, we prospectively evaluated the safety, renal response and overall response rate of higher-dose lenalidomide as part of induction therapy with bortezomib and dexamethasone in TE-NDMM patients presenting with RI at diagnosis. Patients with an eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73m2 received lenalidomide 25 mg on days 1–14 of a 21-day cycle, while those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2—including dialysis-dependent patients—received 15 mg on the same schedule. Here, we report on the safety and tolerability of lenalidomide at doses higher than label recommendations in TE NDMM with RI at diagnosis, along with renal and overall response rates across renal function groups from baseline through four cycles of VRd induction.

Methods

Study design and participants

The REMNANT phase 2 component is an ongoing academic, multicenter, open-label study in TE-NDMM patients aged 18-75 years, with measurable disease defined as serum M-protein ≥10 g/L or involved FLC >100 mg/L. Urine M-protein was not assessed, as it was not routinely available across Norwegian hospitals and has limited diagnostic and prognostic contribution in MM [15,16,17]. Eligibility criteria allowed inclusion of patients with RI, while the key exclusion criterion was prior treatment exceeding one induction cycle (appendix p 2). The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, with approval from national regulatory authorities and the institutional ethics committee in Norway. All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. The trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04513639).

Procedures

In the induction phase, all patients received four 21-day cycles of bortezomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Bortezomib was administered subcutaneously at 1.3 mg/m² on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 (modified to days 1 and 8 after 50% enrollment). Lenalidomide was given orally at 25 mg/day on days 1-14 in patients with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73m2 and at 15 mg/day in those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2, including dialysis-dependent patients (appendix p 3). For patients initiating therapy prior to enrollment (maximum 1 cycle), lenalidomide dosing was adjusted at inclusion. During treatment, lenalidomide dosing was maintained at 15 mg/day for patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 at the start of each cycle, and up to 25 mg/day for those with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2. Dexamethasone was given orally at 20 mg on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12.

Herpes zoster prophylaxis was recommended for all patients. Thromboprophylaxis consisted of low-dose aspirin for standard-risk patients and a direct oral anticoagulant for those with at least one thrombotic risk factor. There was no recommendation on the prophylactic use of antibiotics or immunoglobulins per protocol.

High-risk cytogenetics were defined per International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria [18] as the presence of one or more of del17p, t(4;14) or t(14;16).

Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0). For this sub study, only grade ≥2 AEs deemed relevant to lenalidomide and requiring intervention were included. AEs are reported once per patient.

Renal response was evaluated according to IMWG renal response criteria [19] in patients with baseline eGFR <50 mL/min/1.73m2. eGFR was calculated using the CKD-EPI (creatinine-based) formula.

Disease response was assessed at the start of each cycle by investigators using local laboratory M-protein (g/L), serum free light chain parameters (mg/L) and bone marrow aspirate or biopsy. As previously described, urine M-protein was not measured. A modified response definition, based on the 2016 IMWG criteria for response [20], was applied, in line with the as-yet unpublished updated IMWG criteria for response. The modified definition requires reduction in both M-protein and difference in serum FLC for all response grades when both were measurable at baseline, and normalization of the FLC ratio for complete response in all patients (appendix pp 3-4).

Dose intensity was defined as the ratio of total administered dose to total planned dose. For patients who initiated induction prior to enrollment, the total planned dosed of lenalidomide for treatment days outside the protocol was based on label recommendations: 10 mg/day for eGFR 30-49 mL/min/1.73m2, 7.5 mg/day for eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73m2 in non-dialysis patients and 5 mg/day for dialysis-dependent patients.

Outcomes

This analysis aimed to: (1) assess the safety and tolerability of lenalidomide 25 mg/day (days 1–14), as part of induction therapy, in patients with eGFR 30–49 mL/min/1.73 m²; (2) evaluate the safety and tolerability of lenalidomide 15 mg/day (days 1–14), as part of induction therapy, in patients with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m², including those requiring dialysis; (3) determine renal response during induction in all patients with baseline eGFR <50 mL/min/1.73 m²; and (4) determine overall response rates in patients with eGFR ≥50 mL/min/1.73 m², eGFR 30–49 mL/min/1.73 m² and eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m² from cycle 1 day 1 through the first post-induction visit.

Statistical analysis

Participant characteristics were summarized using proportions for categorical variables and median for continuous variables. For comparisons between groups, the Chi-Square test or Fisher’s exact test (in case of expected cell count below 5 and low total number) were used for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U for continuous variables. All calculations were performed using R-Studio (version 4.4.0).

Results

Baseline characteristics

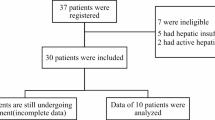

Between August 2020 and September 2024, 382 patients were enrolled across 13 Norwegian institutions and included in this analysis. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of these, 301 patients (79%) had eGFR ≥50 mL/min/1.73 m² (Group A) while 81 (21%) had RI: 37 patients (10%) with eGFR between 30–49 mL/min/1.73 m² (Group B) and 44 (12%) with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m² (Group C), including seven (2%) who were dialysis-dependent during cycle 1.

Median baseline eGFRs were 89 (IQR 76–93; range 51–135), 39 (35–47; 30-49), and 18 (14–22; 4–29) mL/min/1.73 m² in Groups A, B, and C, respectively. Median age was 63 (IQR 56–67; range 32–75) (A), 66 (61–68; 50–73) (B), and 62 years (56–66; 38–72) (C), with males comprising 58%, 70%, and 61% of each group. An involved serum FLC >500 mg/L was observed in 35%, 62%, and 86% in Groups A, B and C, respectively, and median differences in serum FLC levels were 299 (IQR 76–883; range 0–100,256) (A), 1712 (206–4432; 0–26,527) (B), and 2119 (883–5925; 58–21,390) (C) mg/L. Anemia (hemoglobin <10 g/dL or >2 g/dL below lower limit of normal) was present in 43%, 73%, and 93% and bone marrow plasma cell infiltration >50% in 44%, 65%, and 70% of patients in Group A, B and C, respectively. ISS stage III disease was more frequent with worsening RI: 12% (A), 65% (B), and 93% (C). High-risk cytogenetics were identified in 21% (A), 27% (B), and 16% (C). Comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus were similar distributed between the RI and-non RI patients, while non-myeloma-related kidney disease (5% vs 1%, p <0.05) were more frequent in patients with RI.

Safety and adverse events

From baseline through the first post-induction visit, lenalidomide relevant AEs of grade 2 or higher are presented in Table 2. Worsening renal function occurred significantly more often in patients with baseline RI compared to those without (5% vs 0%, p <0.005). Four renal events were recorded in patients with RI: two grade 4 in Group C and two grade 2 events in Group B. In Group C, both patients developed grade 4 worsening renal function requiring dialysis. The first event occurred on day 18 of induction cycle 1 and was considered possibly related to lenalidomide; treatment had already been withheld from day 8 due to a grade 3 COVID-19 infection. The patient became dialysis-independent after 14 days and resumed lenalidomide (15 mg/day) from cycle 2. The second grade 4 event occurred on day 14 of induction cycle 1 during a concurrent grade 3 pneumonia infection, was deemed unrelated to lenalidomide and was followed by fatal varicella infection. In Group B, two patients developed grade 2 renal events. One possibly related to lenalidomide, resolved following temporary interruption and resumption at a reduced dose (15 mg/day). The other, deemed unrelated, resolved after dose-reduction (15 mg/day). Other AEs significantly more frequent in patients with RI included anemia (12% vs 2%, p <0.001) and thrombocytopenia (7% vs 0.3%, p <0.001).

No patient who completed induction demonstrated a decrease in eGFR compared to baseline.

Median relative dose intensity (RDI) for lenalidomide was 100% across all renal function groups for cycles 1–4 (appendix p 5). In cycle 1, RDI medians were 100% (IQR 100–100; range 0–143) for patients with eGFR ≥50 mL/min/1.73 m², 100% (100–100; 0–150) for those with eGFR 30–49 mL/min/1.73 m², and 100% (71–100; 0–133) for those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m². Comparable medians were observed in cycles 2–4; however, lower IQR values were noted in the eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m²group, from cycle 2 onwards (e.g., cycle 2: 100% [IQR 60–100; range 0–100]).

Disease progression occurred in 13 patients (3%): nine in Group A, two in Group B and two in Group C. Five patients (1%) died from AEs—three in Group A (cardiac arrest, infection and flail chest due to myeloma), none in Group B and two in Group C (both infections). None were considered related to lenalidomide. Other reasons for treatment discontinuation included patient choice (n = 7; A: 5, B: 2, C: 0) adverse events (n = 3; A: 2, B: 1, C: 0), physicians decision (n = 6; A: 3, B: 0, C: 3), withdrawal of consent (n = 1; Group A,) and inability to comply (n = 1; Group C). AEs leading to discontinuation included intractable atrial flutter (related to lenalidomide and bortezomib; Group A), diaphragmatic paresis (related to bortezomib; Group A) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (related to lenalidomide and bortezomib; Group B).

As previously described, five on-study deaths were reported, all considered unrelated to lenalidomide. Two occurred in Group C in patients with baseline eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m² who were on dialysis during cycle 1: one patient, who had become dialysis-independent, died from varicella encephalitis, and the other died from Legionnaires’ disease while remaining on dialysis. An additional death in Group C, also in a patient on dialysis at baseline, occurred due to progressive disease within 30 days after the end of treatment, with the patient still receiving dialysis.

Efficacy outcomes

Among the 81 patients with baseline eGFR <50 mL/min/1.73 m² (Groups B and C), 62 (77%) achieved a renal response and 46 (57%) achieved a complete renal response during induction (Table 3). Median eGFR improved from 39 to 66 (IQR 54–86; range 43–100) mL/min/1.73 m² in Group B and from 18 to 58 (38-84; 15–101) mL/min/1.73 m² in Group C, while renal function remained stable in Group A (Fig. 1A). Of the seven patients requiring dialysis during cycle 1, five became dialysis-independent. The remaining two patients died—one from infection while on dialysis and one from progressive disease within 30 days of study completion.

Overall response rates were comparable across groups, 89%, 95% and 82%, in Groups A, B and C, respectively, and very good partial response or better was achieved in 60% (A), 59% (B) and 64% (C) (Table 4). Median differences in serum FLC decreased from 299 to 0 (IQR 0–32; range 0–34,799) mg/L (A), 1712 to 0 (0–102; 0–1140) mg/L (B), and 2119 to 0 (0–129; 0–4799) mg/L (C). (Fig. 1B).

Discussion

This subanalysis of the non-randomized phase 2 component of the REMNANT study demonstrates that lenalidomide, administered at 25 mg/day for patients with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 and at 15 mg/day for those with eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, is both safe and effective as part of induction therapy in TE-NDMM patients with renal impairment. Patients were assessed from baseline through four induction cycles, as rapid reduction of involved serum FLC is the most critical factor for improving renal function [8, 9]. Consequently, efficacious treatment during this period is of utmost importance.

Baseline RI in our study was associated with markers of higher disease burden, as evidenced by more frequent anemia (84% vs 43%, p <0.001), marrow infiltration >50% (68% vs 44%, p <0.001) and involved serum FLC levels >500 mg/l (75% vs 35%, p <0.05). However, other non-myeloma factors may also have contributed to RI [21]. Although patients with RI in our study did not exhibit a higher prevalence of hypertension or diabetes mellitus, non-myeloma kidney disease was significantly more common in these patients compared with those without (5% vs 1%, p <0.05). That being considered, it is likely that renal dysfunction in our study was attributable to aggressive myeloma biology rather than underlying comorbidities in most patients. This observation aligns with prior reports linking high tumor burden and elevated serum FLC to myeloma-related kidney injury, underscoring the importance of early disease control to support renal recovery [4, 6].

Lenalidomide was generally well tolerated. The higher incidence of worsening renal function in patients with RI (5% vs 0%, p <0.005) was largely reversible and often infection related. These findings suggest that lenalidomide-related renal toxicity, though possible, is infrequent and manageable with temporary interruption or dose modification. The higher rates of grade ≥2 anemia and thrombocytopenia (12% vs 2% and 7% vs 0.3%, respectively, both p <0.001) in RI patients are likely multifactorial. Lenalidomide-related myelosuppression is a recognized risk, reduced erythropoietin production due to renal dysfunction, and higher disease burden impairing hematopoiesis (e.g. >50% marrow infiltration in 68% vs 44%, p <0.001), likely contributed. Erythropoietin levels, however, were not assessed. Importantly, neutropenia was not increased in RI patients, and the median relative dose intensity for lenalidomide was maintained at 100% through cycles 1–4, supporting the feasibility of these doses, with appropriate monitoring and supportive care, even in patients with severe RI.

Treatment discontinuations due to AEs were rare (0.8%), and all on-study deaths were considered unrelated to lenalidomide, occurring primarily in patients with severe RI and infection. This underscores that severe RI—particularly in dialyses-dependent patients—is associated with higher infection-related mortality [22], even when events are not directly drug-related. No prophylactic antibiotic regimen was mandated per protocol, and these findings may justify enhanced infectious prophylaxis and closer monitoring in this high-risk subgroup.

Efficacy was preserved across all levels of baseline renal function. Overall response rates were high, with approximately 60% of patients in each group achieving a very good partial response or better. Importantly, RI, including severe RI and dialysis dependence, did not significantly impair hematologic response depth. Renal improvement was observed in the majority of patients with baseline eGFR <50 mL/min/1.73 m2, with 77% achieving a renal response and 57% achieving a complete renal response during induction. Median eGFRs improved markedly in both moderate and severe RI groups, and no patient experienced worsening renal function at the post induction time-point. Additionally, five of seven dialysis-dependent patients became dialysis-independent during induction. These findings are consistent with prior reports [4, 23] demonstrating that effective myeloma-directed therapy can achieve comparable response rates in patients with and without RI, and that rapid disease control improves renal outcomes.

The current IMWG renal response criteria [24] do not classify partial or minor response for patients with baseline eGFR between 30-49 mL/min/1.73m2. This limitation may lead to underestimation of clinically meaningful renal improvement in this subgroup. Of the nine patients in this subgroup who had a stable renal response, four had eGFR >50 ml/min per 1.73 m2 after completing induction. For all nine patients, median eGFR improved from 37 (IQR 36–41; range 30–49) to 49 (46–56; 43–57) mL/min/1.73 m2.

Limitations of this study include its non-randomized design, relatively small size of the RI subgroups and lack of long-term follow-up. Despite these limitations, the low incidence of treatment-related toxicity, the high renal response rate and preserved efficacy across all levels of renal function support the use of full-dose or moderately reduced-dose lenalidomide as part of induction therapy in TE-NDMM patients with RI.

Data availability

De-identified participant data underlying the results reported in this Article will be made available upon reasonable request directed to the corresponding author. The sponsor of the trial, Oslo University Hospital, via the corresponding author, reserves the right to decide on whether to share the data.

References

Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos MV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e538–48.

Chen X, Luo X, Zu Y, Issa HA, Li L, Ye H, et al. Severe renal impairment as an adverse prognostic factor for survival in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34:e23416.

Leung N, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma with acute light chain cast nephropathy. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:46.

Courant M, Orazio S, Monnereau A, Preterre J, Combe C, Rigothier C. Incidence, prognostic impact and clinical outcomes of renal impairment in patients with multiple myeloma: a population-based registry. Nephrol Dialysis Transplant. 2021;36:482–90.

Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou V, Bamias A, Gika D, Simeonidis A, Pouli A, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. Renal failure in multiple myeloma: incidence, correlations, and prognostic significance. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:337–41.

Gonsalves W, Leung N, Rajkumar S, Dispenzieri A, Lacy M, Hayman S, et al. Improvement in renal function and its impact on survival in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e296–e.

Sharma R, Jain A, Jandial A, Lad D, Khadwal A, Prakash G, et al. Lack of renal recovery predicts poor survival in patients of multiple myeloma with renal impairment. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22:626–34.

Szabo AG, Thorsen J, Iversen KF, Hansen CT, Teodorescu EM, Pedersen SB, et al. Clinically-suspected cast nephropathy: a retrospective, national, real-world study. Am J Hematol. 2020;95:1352–60.

Bridoux F, Arnulf B, Karlin L, Blin N, Rabot N, Macro M, et al. Randomized trial comparing double versus triple bortezomib-based regimen in patients with multiple myeloma and acute kidney injury due to cast nephropathy. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2647–57.

Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Boccadoro M, Moreau P, Mateos M-V, Zweegman S, et al. EHA–EMN Evidence-Based Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients with multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2025:1–21.

Agency EM Lenalidomide Accord: EPAR—Product information 2024 [Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/lenalidomide-accord#product-info.

Chen N, Lau H, Kong L, Kumar G, Zeldis JB, Knight R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of lenalidomide in subjects with various degrees of renal impairment and in subjects on hemodialysis. J Clin Pharm. 2007;47:1466–75.

Mikhael J, Manola J, Dueck AC, Hayman S, Oettel K, Kanate AS, et al. Lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma and impaired renal function: PrE1003, a PrECOG study. Blood. Cancer J. 2018;8:86.

Rasmussen A-M, Askeland FB, Schjesvold F. The next step for MRD in myeloma? Treating MRD relapse after first line treatment in the REMNANT study. Hemato. 2020;1:8.

Katzmann JA, Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Snyder MR, Plevak MF, Larson DR, et al. editors. Elimination of the need for urine studies in the screening algorithm for monoclonal gammopathies by using serum immunofixation and free light chain assays. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006.

Banerjee R, Fritz AR, Akhtar OS, Freeman CL, Cowan AJ, Shah N, et al. Urine-free response criteria predict progression-free survival in multiple myeloma: a post hoc analysis of BMT CTN 0702. Leukemia. 2025:1–4.

Dejoie T, Corre J, Caillon H, Hulin C, Perrot A, Caillot D, et al. Serum free light chains, not urine specimens, should be used to evaluate response in light-chain multiple myeloma. Blood, J Am Soc Hematol. 2016;128:2941–8.

Sonneveld P, Avet-Loiseau H, Lonial S, Usmani S, Siegel D, Anderson KC, et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma with high-risk cytogenetics: a consensus of the International Myeloma Working Group. Blood. J Am Soc Hematol. 2016;127:2955–62.

Dimopoulos MA, Merlini G, Bridoux F, Leung N, Mikhael J, Harrison SJ, et al. Management of multiple myeloma-related renal impairment: recommendations from the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:e293–e311.

Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, Durie B, Landgren O, Moreau P, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e328–e46.

Nasr SH, Valeri AM, Sethi S, Fidler ME, Cornell LD, Gertz MA, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in multiple myeloma: a case series of 190 patients with kidney biopsies. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:786–94.

Hutchison CA, Cockwell P, Moroz V, Bradwell AR, Fifer L, Gillmore JD, et al. High cutoff versus high-flux haemodialysis for myeloma cast nephropathy in patients receiving bortezomib-based chemotherapy (EuLITE): a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6:e217–e28.

Uttervall K, Duru AD, Lund J, Liwing J, Gahrton G, Holmberg E, et al. The use of novel drugs can effectively improve response, delay relapse and enhance overall survival in multiple myeloma patients with renal impairment. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101819.

Dimopoulos MA, Sonneveld P, Leung N, Merlini G, Ludwig H, Kastritis E, et al. International Myeloma Working Group recommendations for the diagnosis and management of myeloma-related renal impairment. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1544–57.

Acknowledgements

This is an investigator-initiated study supported by the Norwegian Government (KLINBEFORSK), the Norwegian Cancer Society, MATRIX, J&J Innovative Medicine, BMS/Celgene, the Binding Site, and GSK. The trial is sponsored by Oslo University Hospital (Oslo, Norway). We thank all the patients at centers whose willingness to participate made this study possible; all principal investigators, subinvestigators, study nurses, and research support staff; and the laboratory teams for their contribution to the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FBA revised the protocol, conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. VHB analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. A-MR wrote the protocol, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. AL analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. EH conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. MM conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. ALE conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. GT conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. BDE conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. NML conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. JR conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. VS conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. ES conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. RFH conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. DS conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. AAH conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. ASN conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. TSS conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript. PA analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. FS designed the study, revised the protocol, conducted the clinical trial, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

FBA has received honoraria or payments from J&J and Sanofi, and has participated in advisory boards for J&J and Sanofi. EH has received honoraria or payments from J&J and has participated in advisory boards for Sanofi. MM has received honoraria or payments from J&J and AbbVie, and has participated in advisory boards for Sanofi, AbbVie, Shire, and Lilly. ALE has received honoraria or payments from J&J, Bayer, Pfizer, and Incyte; and participated in advisory boards for Sanofi, J&J, Pfizer, and GSK. GT has received honoraria or payments from J&J, Sanofi, SOBI, and Grifols, and has participated in advisory boards for J&J, Sanofi, SOBI, and Grifols. VS has received honoraria or payments from J&J. TSS has received honoraria for lectures and educational material from Takeda, Celgene, Amgen, J&J, AbbVie, and Pfizer; has received consulting fees from BMS, GSK, Sanofi, Pfizer, and Menarini Group; and has participated in advisory boards for Amgen, Celgene, GSK, J&J, Sanofi, and BMS. FS has received grants from Targovax; has received consulting fees from Caedo Therapeutics; has received honoraria/payment from Amgen, BMS, Takeda, Sanofi, Menarini, AbbVie, J&J, Oncopeptides, and GSK; has participated on advisory boards or data safety monitoring for GSK, Takeda, BMS, J&J, Oncopeptides, Regeneron, Sanofi, XNK Therapeutics, Galapagos, and Pfizer; and is the president of the Nordic Myeloma Study Group (academic group). All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Askeland, F.B., Bugge, V.H., Rasmussen, AM. et al. Optimizing lenalidomide therapy in renal impairment: analysis of renal response in the prospective REMNANT study in transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 15, 214 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01407-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01407-5