Abstract

Teclistamab, a bispecific antibody targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), is effective in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM), but its impact on patients with soft tissue plasmacytomas is unclear. We studied 385 RRMM patients treated with teclistamab at 13 U.S. centers through September 2023, with follow-up to April 2024. Soft tissue plasmacytomas were classified as true extramedullary disease (EMD; not contiguous with bone) or paraskeletal plasmacytomas (PSK; contiguous with bone). Patients with the simultaneous presence of both were classified as true-EMD, reflecting its adverse prognosis. Of those, 109 (28%) had true EMD, 33 (9%) had PSK, and 243 (63%) had no soft tissue plasmacytoma (No-STP). Median follow-up was 9.9 months. Overall response rates were 38% in true-EMD, 54.1% in PSK, and 62.4% in No-STP (p < 0.001). Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 1.4 months in true-EMD, 6.51 months in PSK, and 8.95 months in No-STP (p < 0.0001). Median overall survival (OS) was 9.54 months for true EMD, 13.1 months for PSK, and not reached in No-STP (p = 0.00012). In multivariable analysis, true-EMD was independently associated with inferior PFS and OS, while PSK showed numerically lower outcomes. These findings highlight the need for tailored strategies in patients with soft tissue plasmacytomas, particularly those with true-EMD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, particularly in advanced stages, is associated with the development of aggressive disease features, including extramedullary disease (EMD). EMD develops within an immunosuppressive microenvironment characterized by poor tumor vascularization and stromal barriers that may impede effective T-cell function, posing significant treatment challenges.

True-EMD refers to soft tissue plasmacytomas arising from hematogenous dissemination without connection to bony involvement, commonly affecting sites such as the skin, muscle, liver, kidneys, lymph nodes, CNS, breast, pleura, and pericardium [1]. In contrast, paraskeletal disease (PSK) refers to bone-based plasmacytomas where tumor growth extends into soft tissue following cortical bone disruption. Historically, PSK and true-EMD were grouped together, but newer definitions distinguish true-EMD based on its hematogenous spread [1, 2].

The prevalence of true-EMD has increased in later treatment lines, while PSK remains stable from diagnosis [3]. However, that data is based on the era before the availability of T-cell therapies, and with improving survival, PFS, and shifting treatment landscapes, the true prevalence in the current era of T-cell therapy remains uncertain. Patients with true-EMD experience the shortest survival [4, 5], whereas PSK has historically had less severe, but still adverse, impact on survival [6]. These differences underscore the importance of accurate classification, particularly when evaluating T-cell redirection therapies.

Teclistamab, a bispecific antibody (BsAb) targeting CD3 on T cells and B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) on myeloma cells, was approved in the United States (U.S.) in October 2022 for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) for patients previously treated with four or more prior therapies, including an immunomodulatory agent (IMiD), a proteasome inhibitor (PI), and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody. In the pivotal MajesTEC-1 trial, EMD was defined as soft-tissue lesions not related to bone (true-EMD) [5]. Lesions arising from bone were excluded from EMD classification, in alignment with the previous definition [1]. Among the 165 patients treated with teclistamab, 17% had true-EMD, with a lower ORR of 35% compared to 63% in the overall population [5]. With a median follow-up of 30 months, updated results showed that among responders, the 24-month duration of response (DOR) was 50% in both the true-EMD group (10/28) and the overall recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) cohort (104/165). Rates of death due to disease progression were higher in true-EMD (53.6%) compared to the overall RP2D population (33.9%) [4].

While MajesTEC-1 provided insights into true-EMD outcomes, it did not assess PSK separately or compare it to marrow-contained disease, who have no soft tissue plasmacytomas. Additionally, real-world patients often differ from clinical trial populations in terms of prior treatments, comorbidities, and response patterns. This study evaluated teclistamab’s real-world efficacy across distinct EMD classifications—true-EMD, PSK, and No-STP (without soft tissue plasmacytoma)—to address these gaps and provide a more comprehensive understanding of outcomes beyond controlled trial settings.

Methods

This was a retrospective multicenter study, evaluating patients with RRMM at 13 medical centers in the U.S. Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium, who received teclistamab by September 2023, with follow-up through April 30, 2024 (Supplementary Fig. 1—Consort diagram). Each center obtained independent Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent in accordance with institutional requirements.

Patients included in the study were classified into three groups based on center-reported data: (1) true-EMD, defined as soft tissue (visceral or non visceral) plasmacytomas non-contiguous with bone; (2) PSK, characterized by soft tissue extension from bone-based lesions; and (3) No-STP, patients without soft tissue plasmacytomas. Patients with both PSK and true-EMD simultaneously were categorized as true-EMD, due to its adverse prognosis. Patients were classified into three cytogenetic risk groups based on a modified version of the 2025 International Myeloma Society (IMS)/International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) consensus criteria [7]: (1) standard risk, (2) confirmed high-risk, defined as t(4;14), t(14;16), or t(14;20) in combination with either gain/amp(1q) or del(1p), or concomitant gain/amp(1q) and del(1p) (including cases with concurrent del(17p)), and (3) isolated del(17p), categorized separately if not meeting criteria for confirmed high-risk, regardless of variant allele frequency or clonal fraction, given the absence of TP53 mutation data and incomplete FISH threshold information. In our study, patients reported with plasma cell leukemia (PCL) diagnosed between 2017 and 2022 were included based on chart documentation. During this period, the diagnostic criteria for PCL changed (from ≥2 × 10⁹/L circulating plasma cells before 2021 to ≥5% circulating plasma cells or ≥0.5 × 10⁹ cells/L of plasma cells in peripheral blood [8]; therefore, PCL classification was based on the documented diagnosis rather than uniform reapplication of updated definitions. Additionally, information regarding primary versus secondary PCL was not available in the dataset.

Response was assessed by treating investigators using the IMWG criteria [9]. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, not all IMWG criteria were strictly applied. Confirmatory testing for complete responses (CR) was not required, and therefore, some CRs may not fully meet IMWG criteria. Patients with hematologic response, but imaging progression, were classified as having progressive disease for the overall response rate (ORR) analysis. If imaging was unavailable during the best hematologic response, the response was determined based on available hematologic criteria. For patients with true-EMD or PSK, hematologic and radiographic responses were evaluated when available. Radiographic response was assessed based on available imaging modalities as reported by each center, recognizing variability in imaging timelines and methods across institutions. Imaging methods, including PET/CT, CT, or MRI, depending on institutional practice (Supplementary Table 1). Any increases in plasmacytomas during Cycle 1 were not considered disease progression to avoid misinterpreting tumor flares [10,11,12]. Patients who died before response assessment were classified as hematological non-responders.

Statistical analysis

For the overall cohort, comparisons among groups of interest (true-EMD vs. PSK vs. No-STP) were conducted using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum tests for continuous variables. Duration of response (DOR) was measured from the first documented response (PR or better) until disease progression. Patients without progression at the last follow-up or those who died without progression were censored. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from initiation of teclistamab to progression or death, whichever occurred first. Patients who remained alive and free from progression were censored at their last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from initiation of teclistamab until death. Survival distributions were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and subgroups were compared using the log-rank test. Univariate Cox regression models were constructed, incorporating pre-specified covariates, including age at first teclistamab, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status at teclistamab, PCL at any time through the myeloma course, STP type at the time of teclistamab initiation, cytogenetic abnormalities per Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) at any time, prior BCMA-directed therapy, triple-class, and penta-refractory status. Variables with a p value < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 4.3.1), and SPSS (V29.0). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of 385 patients treated with teclistamab, 109 (28%) had true-EMD, 33 (9%) had PSK, and 243 (63%) had No-STP at the time of teclistamab initiation. In the true-EMD cohort, 54% (n = 59) had visceral disease involvement, and 72% (n = 79) presented with more than one EMD lesion at teclistamab initiation. One third of patients with true-EMD had known concurrent PSK disease (n = 33, 30%), while the presence of PSK along with EMD is unknown for 38% (n = 41) of patients. In the PSK cohort, 45% (n = 15) had multiple disease sites.

The median age of the entire cohort was 68 years (range, 31.2–92), with 50% having received prior BCMA-directed therapy. The median time from MM diagnosis to teclistamab initiation was 5.8 years (interquartile range (IQR), 3.5–9.3 years).

Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2, and were generally comparable across the three groups, except that patients with true-EMD and PSK were younger and had received more prior BCMA-directed therapies. There were no significant differences between groups regarding high-risk cytogenetics, penta-refractory disease, or median prior lines of therapy.

Safety

Adverse effects are summarized in Table 2. There were no significant differences observed in the incidence and severity of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) between true-EMD, PSK, and No-STP (any grade: 52% vs. 54.5% vs. 59%, p = 0.3; grade ≥2: 8% vs. 6% vs. 12%, p = 0.4). There was no difference in median onset and duration of CRS across groups.

There were no significant differences observed in the incidence of immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) between true-EMD, PSK, and No-STP (any grade: 16% vs. 15% vs. 13%, p = 0.7), however, patients in the PSK group had a higher rate of ICANS grade ≥2 at 15%, compared to 9% in the true-EMD group and 5% in the No-STP group (p = 0.045). The median time to onset of ICANS was comparable across groups (p = 0.2).

There were no differences between groups regarding the use of tocilizumab, corticosteroids, or anakinra for either CRS or ICANS, except for a higher use of corticosteroid in the PSK group, which attributed to a greater incidence of high-grade ICANS. The primary cause of treatment discontinuation across all groups was disease progression, with a significantly higher incidence in the true-EMD group (82%) compared to 65% in the PSK group and 60% in the No-STP group (p = 0.003).

Response rates

The hematologic and radiographic response rates for each STP group are presented in Fig. 1. The hematologic overall response rate (ORR; partial response [PR] or better) was 38% in the true-EMD group, 54.1% in the PSK group, and 62.4% in the No-STP group (p < 0.001). The rates of complete response (CR) or better were 12%, 21%, and 28% in the true-EMD, PSK, and No-STP groups, respectively (p = 0.006). Pairwise comparisons showed no significant difference in ORR between the No-STP and PSK groups (OR = 0.69, 95% CI: 0.3–1.4, p = 0.33), while patients with true-EMD had significantly lower odds of response compared with those without STP (OR = 0.37, 95% CI: 0.23–0.59, p < 0.001), corresponding to an approximately 63% decrease in odds of response. The comparison between true-EMD and PSK trended toward lower odds but was not statistically significant (OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.24–1.16, p = 0.11). Similar patterns were observed for CR (data not shown).

Radiographic data were available for 79% (112/142) of patients with soft tissue plasmacytoma (true-EMD or PSK) at baseline. Among patients who did not experience early death (<1 month) or progression within the first treatment cycle, radiographic follow-up was available in 87% (92/106).

Radiographic response was evaluable in 62% (n = 68) of the true-EMD group and 73% (n = 24) of the PSK group. Among the true-EMD group, 56% (38/68) had progression of disease (PD), or stable disease (SD) as best response, 10% (7/68) achieved PR, and 34% (23/68) achieved CR, with ORR of 44%. In the PSK group, 33% (8/24) had best response of PD, or SD, 37.5% (9/24) achieved PR, and 29% (7/24) achieved CR, with ORR of 66.5% (p = 0.009). Among the remaining 50 true-EMD or PSK patients, radiographic response was not evaluable if they died or progressed rapidly within the first month of treatment or unable to complete the first cycle of treatment for other reasons (38/50; 76%), lacked available imaging (12/50; 24%) (Supplementary Table 3).

The DOR was evaluable in 80% (169/210) of responders. The median DOR was 8.06 months (95% CI: 6.18–NR) for the true-EMD, 8.49 months (95% CI: 6.45–NR) for the PSK, and 12.86 months (95% CI: 11.05–NR) for the No-STP group (p = 0.011) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Pairwise comparisons showed a significantly shorter DOR in true-EMD compared to No-STP (p = 0.008), while differences between true-EMD and PSK (p = 0.6) and between PSK and No-STP (p = 0.1) were not statistically significant.

Survival outcomes

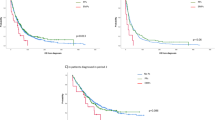

The median follow-up time from teclistamab initiation was 9.9 months (95% CI: 9.5–10.6 months). The median PFS for the entire cohort was 6.1 months (95% CI: 4.6–8.1); the median PFS was 1.4 months (95% CI: 0.98–3.98) for the true-EMD, 6.51 months (95% CI: 3.48–NR) for the PSK, and 8.95 months (95% CI: 6.7–12.1) for the No-STP group (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A). Pairwise comparisons showed no significant difference between No-STP and PSK groups (p = 0.28), while both true-EMD vs. No-STP (p = 0.000000014) and true-EMD vs. PSK (p = 0.041) were statistically significant.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of PFS (A) and OS (B) in patients with RRMM who received teclistamab. Total of 137 events (progressions n = 101; deaths from any other causes n = 36); The median PFS was 1.4 months (95% CI: 0.98–3.98) for the true-EMD, 6.51 months (95% CI: 3.48–NR) for the PSK, and 8.95 months (95% CI: 6.7–12.1) for the No-STP group (p < 0.0001). The median OS was 9.54 months (95% CI: 4.54–NR) for the true-EMD, NR (95% CI: 13.12–NR) for the PSK, and NR for the No-STP group (95% CI: 16.1–NR) (p = 0.00012).

The median OS for the entire cohort was 16.1 months (95% CI: 14.3–NR). By group, the median OS was 9.54 months (95% CI: 4.54–NR) for the true-EMD, NR (95% CI: 13.12–NR) for the PSK, and NR for the No-STP group (95% CI: 16.1–NR) (p = 0.00012) (Fig. 2B). Pairwise comparisons showed no significant difference between No-STP and PSK groups (p = 0.9). There was a trend toward worse OS between true-EMD compared with PSK (p = 0.074), while true-EMD had significantly worse OS compared with No-STP (p = 0.000084).

Across the cohort, 137 deaths were recorded, with 74% (101/137) primarily attributed to disease progression. Among those who died, progression accounted for 82% (45/55) in the true-EMD group, 80% (8/10) in the PSK group, and 67% (48/72) in the No-STP group. The cumulative incidence of non-relapse mortality (NRM) was 26% (36/137), with infection being the leading cause (47%,17/36). The distribution of NRM was similar across the groups, occurring in 9% (10/109) in the true-EMD, 6% (2/33) in the PSK, and 10% (24/243) in the No-STP group (Table 2).

Factors predicting survival

We conducted a univariate analysis to assess the impact of various factors on PFS and OS. Variables with a p value < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were incorporated into the multivariable model. The results are summarized in Table 3.

In the multivariable analysis of the entire cohort, true-EMD at the time of teclistamab (p < 0.001; HR = 1.93; 95% CI, 1.44–2.60) was independently associated with inferior PFS. Additionally, younger age, poor performance status at the time of teclistamab and confirmed high-risk cytogenetic were associated with worse PFS.

For OS, the multivariable analysis found true-EMD at the time of teclistamab (p < 0.001; HR = 2.40; 95% CI, 1.65–3.50) as an association with worse outcome. Additionally, penta-refractory disease, PCL at any time, and poor performance status at the time of teclistamab were associated with inferior OS. Consistent results for both PFS and OS were observed after excluding patients who had PCL at any time point (N = 12) from the analysis (Supplementary Table 4).

Within the true-EMD cohort only, multivariable analysis revealed that younger age was associated with worse PFS. Similarly, younger age, in addition to PCL at any time point, and poor performance status, were associated with inferior OS (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

This multicenter retrospective study represents the first analysis of the impact of soft tissue plasmacytomas (true-EMD and PSK) on outcomes in a large cohort of RRMM patients treated with teclistamab. Our findings highlight that true-EMD is independently associated with inferior PFS and OS, providing valuable insights into the management of these complex cases.

True-EMD remains a strong predictor of poor prognosis even in the era of immune effector cell therapies such as BsAbs and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy. In the phase II KarMMa trial of idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel), 39% of patients had soft tissue plasmacytoma (true-EMD and PSK), with an ORR of about 70%, comparable to the 73% response rate in the overall population [13]. However, data on DOR and PFS specifically for patients with STP were not reported. Similarly, CARTITUDE-1, which evaluated ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel), included 20% of patients with soft tissue plasmacytomas (13% true-EMD, 6% PSK), reporting a 100% ORR but shorter median DOR (12.9 months) and PFS (13.8 months) compared to the overall cohort (not reached). At 27 months, PFS and OS rates were lower in the STP subgroup (47.4% vs. 54.9% and 52.1% vs. 70.4%, respectively) [14]. A retrospective real-world study of cilta-cel beyond the 4th line found that true-EMD was independently associated with poorer outcomes. Patients with true-EMD (26% of the cohort) had significantly shorter median PFS (9.1 vs. 12.9 months in those without, p < 0.001). True-EMD was associated with inferior PFS (HR: 1.96, p = 0.009) and OS (HR: 1.88, p = 0.04) in multivariable analysis [15]. Other studies also confirmed worse outcomes for true-EMD with significantly shorter PFS and OS with BCMA CAR-T therapy [16,17,18]. Similarly, the MyCARe model, developed to predict early relapse after BCMA CAR-T therapy, identified the presence of true-EMD or PCL as a significant risk factor for early progression (HR: 1.92, p < 0.001) [19].

T cell engager anti-BCMA BsAb therapies have also shown poorer outcomes in soft tissue plasmacytomas. Understanding the factors driving this resistance is crucial for optimizing treatment strategies. The MajesTEC-1 trial, which led to approval of teclistamab, defined EMD as true-EMD and included 17% patients with EMD. EMD patients had a lower ORR of 35%, compared to 63% in the overall population; however, among responders, the 24-month DOR was comparable (50% in both groups) [5]. Similarly, the MagnetisMM-3 trial, which led to elranatamab’s approval, defined EMD more broadly (including both true-EMD and PSK), and reported an ORR of 38.5% in patients with soft tissue plasmacytomas, compared to 71.4% in those without. Despite lower initial responses, the 15-month DOR was similar (77.9% vs. 70.6%) [20]. This may suggest that while soft tissue plasmacytomas are less responsive initially, once a response is achieved, durability is maintained. However, limited data exist regarding the differential outcomes of PSK compared to true-EMD, with PSK often being inconsistently categorized in clinical trial datasets.

Our retrospective study confirms the negative impact of true-EMD on survival outcomes [16, 17]. By distinguishing true-EMD from PSK, our study emphasizes that only true-EMD carries an adverse prognostic significance, thereby refining the understanding of extramedullary disease in this setting. Although PSK did not emerge as an independent predictor of outcome, patients with PSK experienced numerically lower response rate, shorter DOR, and survival compared to those without STP. These findings suggest that PSK remains clinically relevant, even if not a standalone prognostic factor. Unlike prior studies that reported similar DOR among responders with and without soft tissue plasmacytomas, our findings indicate a shorter DOR in true-EMD patients. However, this should be interpreted with caution, as our timing of baseline first response for calculation of DOR was primarily based on hematologic response criteria, which were more readily available in the majority of cases. This could have influenced DOR estimates, particularly in the absence of standardized imaging at response confirmation. Additionally, the retrospective nature of our study limits direct comparison with prospective trials that have reported durable responses among soft tissue plasmacytoma responders. Our clinical findings align with existing research on the genomic complexity of soft tissue plasmacytoma, offering a clearer understanding of the progression and its impact on clinical outcomes. Genomic studies show that PSK and true-EMD have increased complexity compared to bone marrow-based myeloma, with true-EMD displaying the highest genomic complexity [21]. Transcriptomic analysis of true-EMD samples identified the co-occurrence of 1q21 gain/amplification and MAPK pathway mutations in 79% (11/14) of cases [22]. The CoMMpass dataset confirmed this correlation, showing that only KRAS mutations combined with 1q21 gain/amplification, rather than either alone at diagnosis, elevated the risk of developing soft tissue plasmacytomas (HR = 2.4, p = 0.011) [22]. Additionally, NRAS, KRAS, BRAF, and TP53 mutations were identified in true-EMD cases, highlighting the potential for targeting the RAS-MAPK pathway as a therapeutic strategy [23]. While our study lacks access to pathway mutation data, we specifically evaluated 1q gain/amplification and found no significant difference between our compared groups (data not shown), suggesting that additional genomic drivers may be at play in our cohort.

In our study, prior BCMA-directed therapy was linked to lower PFS in univariable analysis but lost significance in multivariable analysis, suggesting other risk factors may diminish its impact. This aligns with real-world cilta-cel data (p = 0.08) showing a similar trend [15]. However, the strong association of true-EMD with inferior PFS and OS underscores its critical role in treatment decisions. Importantly, although patients with true-EMD were younger and had received more prior BCMA-directed therapies, the inferior outcomes observed were unlikely to be solely attributable to prior treatment history or underlying disease burden. Rather, our findings suggest that teclistamab monotherapy may be insufficient to fully overcome the aggressive biology associated with true-EMD. The strong association of true-EMD with inferior PFS and OS underscores its critical role in treatment decisions. Similar trends have been observed in real-world data [24], which reported that the presence of true-EMD/PCL is an independent adverse prognostic factor in patients treated with BCMA-directed therapies, associated with worse PFS and OS. Notably, although outcomes varied by drug class—with CAR-T therapy achieving the best survival, followed by T-cell engagers (TCEs), and Antibody-drug-conjugates (ADCs) performing the least favorably—the negative impact of true-EMD/PCL persisted across all treatment modalities. Importantly, our sensitivity analysis demonstrated that true-EMD remains independently associated with inferior PFS and OS even when patients with PCL were excluded (Supplementary Table 4), highlighting the prognostic impact of EMD regardless of PCL status.

Several strategies are being investigated to enhance BsAb efficacy across multiple patient subgroups, including those with high-risk features such as true-EMD and PSK. First, debulking strategies have been explored to enhance immunotherapy efficacy. A case report described a patient requiring high-dose steroids and radiation (XRT) for spinal cord compression post-BCMA CAR-T, where CRS-like symptoms and inflammatory spikes coincided with >30% increased T-cell receptor (TCR) diversity, suggesting radiation-induced synergy [25]. Similarly, chemotherapy-based debulking has been investigated. Preclinical studies showed that prior chemotherapy impairs T-cell function by damaging mitochondrial reserves, reducing proliferation and persistence [26, 27]. Clinically, our retrospective analysis of bridging therapy before ide-cel found worse PFS in patients receiving intensified/infusional alkylators (primarily cyclophosphamide [Cy]) [28]. However, in contrast to CAR-T, in vivo data suggest Cy enhances BCMA BsAb therapy by reducing the exhausted T cells and regulatory T cells and preserving a functional naïve/central memory T-cell pool [29]. While a small retrospective study supported a Cy combination debulking strategy prior to BsAb [30], further validation is needed. Our study did not include data on prior alkylator use before teclistamab, limiting direct comparisons. Additionally, 12% of true-EMD patients in our cohort received XRT during teclistamab therapy, with no significant difference in PFS between the XRT and non-XRT groups. However, given the small sample size, this finding should be interpreted with caution. Second, combination therapy may enhance efficacy. In the Phase 1b RedirecTT-1 trial, teclistamab combined with the anti-GPRC5D BsAb, talquetamab, showed promising results. In the RP2D cohort, the ORR was 61% in true-EMD patients (definition was restricted to bone-independent lesions ≥2 cm) versus 92% in those without. The estimated 18-month PFS rate was 53% for true-EMD and 70% in the overall RP2D cohort, supporting its potential in these high-risk patients [31]. Overall, while retrospective data and early-phase studies suggest that debulking or combination strategies may enhance bispecific antibody efficacy, prospective trials are needed to validate these approaches across different patient subgroups, including those with true-EMD and PSK.

Our study’s strengths include its large, diverse cohort treated with teclistamab across multiple institutions, enhancing generalizability. However, as a retrospective analysis, it faces limitations such as potential selection bias, missing data, and variability in investigator-led response assessments. First, CR definitions were based on investigator assessment without confirmatory bone marrow or imaging in most cases, so rates may not reflect strict IMWG-defined CR. Second, there was no uniform requirement for whole-body imaging (e.g., PET/CT, whole-body MRI, or CT) at baseline or during follow-up, and imaging was performed and reported at the discretion of treating investigators. As a result, while baseline imaging was documented in a subset of patients (including 72% with true-EMD, 100% with PSK, and 38% with No-STP), some patients may have been misclassified as not having EMD or PSK due to unreported or undocumented imaging. Third, the dosing frequency and schedule of teclistamab were not standardized and were left to investigator discretion, which may have affected response timing and outcomes. Furthermore, the absence of a standardized imaging protocol for plasmacytoma evaluation, with responses often determined by hematologic criteria when imaging was unavailable, may introduce discrepancies, particularly between serological and plasmacytoma responses [32].

Nevertheless, the multicenter real-world nature of the cohort offers valuable insights into teclistamab outcomes, including in this high-risk subgroup.

In conclusion, our data underscores the prognostic significance of true-EMD in patients treated with teclistamab. PSK was not an independent prognostic factor, but its potential impact on response and disease progression warrants further study. Future clinical trials should differentiate true-EMD from PSK to better characterize disease patterns. Strategies targeting true-EMD, including localized debulking or rational combination therapies, may help optimize outcomes, with careful consideration of PSK when relevant.

Data availability

Available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bladé J, Beksac M, Caers J, Jurczyszyn A, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Moreau P, et al. Extramedullary disease in multiple myeloma: a systematic literature review. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:45.

Bhutani M, Foureau DM, Atrash S, Voorhees PM, Usmani SZ. Extramedullary multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2020;34:1–20.

Rosiñol L, Beksac M, Zamagni E, Van de Donk N, Anderson KC, Badros A, et al. Expert review on soft-tissue plasmacytomas in multiple myeloma: definition, disease assessment and treatment considerations. Br J Haematol. 2021;194:496–507.

Costa LJ, Bahlis NJ, Usmani SZ, van de Donk NWCJ, Nooka AK, Perrot A, et al. MM-328 efficacy and safety of teclistamab in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) with high-risk (HR) features: a subgroup analysis from the phase 1/2 MajesTEC-1 study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024;24:S546–7.

Moreau P, Garfall AL, van de Donk N, Nahi H, San-Miguel JF, Oriol A, et al. Teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:495–505.

Jiménez-Segura R, Rosiñol L, Cibeira MT, Fernández de Larrea C, Tovar N, Rodríguez-Lobato LG, et al. Paraskeletal and extramedullary plasmacytomas in multiple myeloma at diagnosis and at first relapse: 50-years of experience from an academic institution. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:135.

Avet-Loiseau H, Davies FE, Samur MK, Corre J, D’Agostino M, Kaiser MF, et al. International Myeloma Society/International Myeloma Working Group consensus recommendations on the definition of high-risk multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:2739–51.

Fernández de Larrea C, Kyle R, Rosiñol L, Paiva B, Engelhardt M, Usmani S, et al. Primary plasma cell leukemia: consensus definition by the International Myeloma Working Group according to peripheral blood plasma cell percentage. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:192.

Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, Durie B, Landgren O, Moreau P, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e328–46.

Jamet B, Bodet-Milin C, Moreau P, Kraeber-Bodéré F, Touzeau C. 2-[18 F]FDG PET/CT flare-up phenomena following T-cell engager bispecific antibody in multiple myeloma. Clin Nucl Med. 2023;48:e230–1.

Leipold AM, Werner RA, Düll J, Jung P, John M, Stanojkovska E, et al. Th17.1 cell driven sarcoidosis-like inflammation after anti-BCMA CAR T cells in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2023;37:650–8.

Forsberg M, Beltran S, Goldfinger M, Janakiram M, Kalbi D, Verma A, et al. Phenomenon of tumor flare with talquetamab in a patient with extramedullary myeloma. Haematologica. 2024;109:2368–71.

Munshi NC, Anderson LD Jr, Shah N, Madduri D, Berdeja J, Lonial S, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:705–16.

Martin T, Usmani SZ, Berdeja JG, Agha M, Cohen AD, Hari P, et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, an anti-B-cell maturation antigen chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: CARTITUDE-1 2-year follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:1265–74.

Sidana S, Patel KK, Peres LC, Bansal R, Kocoglu MH, Shune L, et al. Safety and efficacy of standard-of-care ciltacabtagene autoleucel for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2025;145:85–97.

Dima D, Abdallah AO, Davis JA, Awada H, Goel U, Rashid A, et al. Impact of extraosseous extramedullary disease on outcomes of patients with relapsed-refractory multiple myeloma receiving standard-of-care chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14:90.

Zanwar S, Sidana S, Shune L, Puglianini OC, Pasvolsky O, Gonzalez R, et al. Impact of extramedullary multiple myeloma on outcomes with idecabtagene vicleucel. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17:42.

Ferment B, Lambert J, Caillot D, Lafon I, Karlin L, Lazareth A, et al. French early nationwide idecabtagene vicleucel chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy experience in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (FENIX): a real-world IFM study from the DESCAR-T registry. Br J Haematol. 2024;205:990–8.

Gagelmann N, Dima D, Merz M, Hashmi H, Ahmed N, Tovar N, et al. Development and validation of a prediction model of outcome after B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1665–75.

Lesokhin AM, Tomasson MH, Arnulf B, Bahlis NJ, Miles Prince H, Niesvizky R, et al. Elranatamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: phase 2 MagnetisMM-3 trial results. Nat Med. 2023;29:2259–67.

Maclachlan KH, Garces J-J, Shekarkhand T, Rajeeve S, Hashmi H, Hassoun H, et al. Genomic complexity correlates with the degree of marrow independence of malignant plasma cells in the context of extramedullary disease. Blood. 2024;144:248.

Jelinek T, Zihala D, Sevcikova T, Anilkumar Sithara A, Kapustova V, Sahinbegovic H, et al. Beyond the marrow: insights from comprehensive next-generation sequencing of extramedullary multiple myeloma tumors. Leukemia. 2024;38:1323–33.

Bingham N, Shah J, Wong D, Lim SL, Bergin K, Kalff A, et al. Whole genome sequencing and the genetics of extramedullary disease in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2025;15:5.

Rees MJ, Mammadzadeh A, Bolarinwa A, Elhaj ME, Bohra A, Bansal R, et al. Clinical features associated with poor response and early relapse following BCMA-directed therapies in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14:122.

Smith EL, Mailankody S, Staehr M, Wang X, Senechal B, Purdon TJ, et al. BCMA-targeted CAR T-cell therapy plus radiotherapy for the treatment of refractory myeloma reveals potential synergy. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7:1047–53.

Das RK, O’Connor RS, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Lingering effects of chemotherapy on mature T cells impair proliferation. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4653–64.

Das RK, Vernau L, Grupp SA, Barrett DM. Naïve T-cell deficits at diagnosis and after chemotherapy impair cell therapy potential in pediatric cancers. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:492–9.

Afrough A, Hashmi H, Hansen DK, Sidana S, Ahn C, Peres LC, et al. Real-world impact of bridging therapy on outcomes of ide-cel for myeloma in the U.S. Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium. Blood Cancer J. 2024;14:63.

Meermeier EW, Welsh SJ, Sharik ME, Du MT, Garbitt VM, Riggs DL, et al. Tumor burden limits bispecific antibody efficacy through T cell exhaustion averted by concurrent cytotoxic therapy. Blood Cancer Discov. 2021;2:354–69.

Chalopin T, Demarquette H, Pieragostini A, Sonntag C, Jacquet C, van De Wyngaert Z, et al. Debulking conventional chemotherapy before treatment by anti-BCMA bispecific antibody in extramedullary and/or high tumor burden relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2024;144:1986.

Cohen YC, Magen H, Gatt M, Sebag M, Kim K, Min CK, et al. Talquetamab plus teclistamab in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:138–49.

Zhou X, Flüchter P, Nickel K, Meckel K, Messerschmidt J, Böckle D, et al. Carfilzomib based treatment strategies in the management of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma with extramedullary disease. Cancers. 2020;12:1035.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the patients who participated in this study as well as the research personnel at all study sites.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA, DD, BR, AJC, LDA, and HCL contributed to the study design. All authors contributed to data acquisition. AA, UG, DD, BR, AJC, LDA, and HCL contributed to data analysis and interpretation. AA wrote the original draft of the manuscript and incorporated the comments by the co-authors in all subsequent drafts. AA, DD, BR, UG, AS, OP, MAV, CJF, RB, JK, JAD, MRG, AL, MSR, KJ, FA, LS, SD, AFG, EO, GDA, SPS, AJP, DS, EE, HH, LM, GK, JPM, AR, MMH, OC, FLL, SR, YL, SA, DWS, PMV, SR, ALG, SS, KKP, DKH, AJC, LDA, and HCL contributed patients to this analysis, provided critical feedback, and approved of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AA reports Advisory role for Karyopharm, BMS, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and research funding from Abbvie, Adaptive Biotech, K36-therapeutics, for Johnson & Johnson, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. DD reports Advisory role for Karyopharm. BR reports advisory role for Johnson & Johnson. CJF reports consulting: Johnson & Johnson; Research: Johnson & Johnson, Regeneron; ownership of publicly traded stock: Affimed. RB reports consulting: Adaptive Biotech, BMS, Caribou Biosciences, Genentech, Gilead, Johnson & Johnson, Karyopharm, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, Sanofi, SparkCures; Research: Abbvie, BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Pack Health, Prothena, Sanofi. JK reports consulting: GPCR, Johnson & Johnson, Prothena, Legend Biotech; research: Prothena, Ascentage, Johnson & Johnson, Karyopharm, GPCR. JAD reports consultancy for BMS, Johnson & Johnson; speaker’s bureau for Johnson & Johnson. MRG advisory board to BMS and Arcellx. KJ reports advisory board consultant for Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, and BioLineRx. FA reports advisor role and speaker for BMS, Celgene, Caribou biosciences; research funding from Allogene Therapeutic, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Caribou Biosciences. LS reports consulting for Johnson & Johnson, BMS, Novartis. AFG-C reports advisory board, speaker bureau for Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer; Advisory board for BMS, and sperak bureau for Amgen and Cellectar. SPS-A reports research from Johnson & Johnson, and consultancy for Sanofi and Johnson & Johnson. AJP reports consulting from Karyopharm, Capvision. HH reports consulting for Johnson & Johnson; speaker bureaus for Johnson & Johnson, Karyopharm. LM reports advisory board with Legend Biotech and BioLineRx. GK reports consulting: BMS, Arcellx, Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Cellectar, Pfizer, Kedrion; Research: BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Abbvie. JPM reports honoraria: Kite/scitmentum, a Gilead company, AlloVir, Nektar, Sana Biotechnology, BMA, Sanofi, Novartis, CRISPR Therapeutics, CARGO Therapeutics, Autolus, Legend Biotech. Consulting or Advisory Role: Kite, a Gilead company, Juno Therapeutics, AlloVir, Magenta Therapeutics, EcoR1 Capital, CRISPR Therapeutics, and Speakers’ Bureau: Kite/Gilead. Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Fresenius Biotech (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Bellicum Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Gamida Cell (Inst), Pluristem Therapeutics (Inst), Kite, a Gilead company (Inst), AlloVir (Inst). AR reports Consulting from Johnson & Johnson, BMS, Sanofi, Karyopharm and research support from Johnson & Johnson, Caribou, BMS. OC reports consulting from Legend Biotech Inc, BMS, and Johnson & Johnson. SR reports advisory board from Pfizer, Prothena Biosciences, and kite, and research from Nexcella Inc, Poseida and Johnson & Johnson. YL reports consulting from Johnson & Johnson, Legend, Celgene, Sanofi, BMS, Pfizer, Regeneron, Genentech, NexImmune, Caribou; research funding from Johnson & Johnson, Celgene, BMS. SA reports research funding: GSK, Amgen, Karyopharm; honoraria: Johnson & Johnson. DS reports consulting from Sanofi, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, Legend Biotech, Bioline, AstraZeneca, Arcellx, Abbvie, Genentech, Opna Bio, and research from Pfizer. PMV reports consultancy for Abbvie, AstraZeneca; BMS, Karyopharm, Lava Therapeutics, Sanofi; Regeneron, Johnson & Johnson, GSK; research funding: Abbvie, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Regeneron. SR reports honoraria from Johnson & Johnson, BMS, Genentech, Karyopharm Therapeutics, MJH LifeSciences; steering committees: Gracell Therapeutics, BMS; research support: Johnson & Johnson, BMS, C4 Therapeutics, Gracell Therapeutics, Heidelberg Pharma; consulting: Genentech, Johnson & Johnson, BMS, Karyopharm Therapeutics. FLL reports Scientific Advisory Role/Consulting Fees: A2, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Adaptimmune, Allogene, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bluebird Bio, BMS, Calibr, Caribou, EcoR1, Gerson Lehrman Group (GLG), Iovance, Kite Pharma, Janssen, Legend Biotech, Miltenyi, Novartis, Sana, Pfizer, Poseida. Data Safety Monitoring Board: Data and Safety Monitoring Board for the NCI Safety Oversight CAR T-cell Therapies Committee. Research Contracts or Grants to my Institution for Service: 2SeventyBio (Institutional), Allogene (Institutional), BMS (Institutional), Incyte (Institutional), Kite Pharma (Institutional), Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research (PI: Locke), Mark Foundation, National Cancer Institute, Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Several patents held by the institution in my name (unlicensed) in the field of cellular immunotherapy. Education or Editorial Activity: Aptitude Health, ASH, ASTCT, Clinical Care Options Oncology, Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer. ALG reports research funding: Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Tmunity, CRISPR Therapeutics; consulting: Johnson & Johnson, Gracell, BMS, GSK, Regeneron, Abbvie, Smart Immune; IDMC membership for Johnson & Johnson. SS reports research: Magenta Therapeutics, BMS, Allogene, Johnson & Johnson, Novartis, Abbvie; Advisory Board/Consultancy: BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Oncopeptides, Takeda, Regeneron, Abbvie, Pfizer, BiolineRx, Legend, Kite. KKP reports advisory/Consultancy from Johnson and Johnson, BMS, Legend Bioteh, Pfizer, Takeda, Sanofi, Oricel, Kite, Arcellx, Caribou Sciences, Novartis, Takeda, Regeneron, Poseida. DKH reports research funding from BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Karyopharm, Kite Pharma, and Adaptive Biotech; Consulting or advisory role for BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Legend Biotech, Pfizer, Kite Pharma, AstraZeneca, and Karyopharm. AJC reports consulting: Abbvie, Adaptive, BMS, HopeAI, Johnson & Johnson, Sebia, Sanofi; Research: Abbvie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Caelum, Harpoon, Nektar, BMS, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, OpnaBio, IgM Biosciences, Regeneron. LDAJ reports consulting: Johnson & Johnson, Celgene, BMS, Amgen, GSK, AbbVie, Beigene, Cellectar, Sanofi, Prothena. Research: BMS, Celgene, Johnson & Johnson, Abbvie. HCL reports consulting: BMS, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, Regeneron, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Abbvie, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Allogene Therapeutics, Menarini, Alexion Pharmaceuticals; research funding: Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, GSK, Regeneron, Takeda Pharmaceuticals. The rest of the authors have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board or ethics committee at each participating institution (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle, WA; Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC; Myeloma, Waldenstrom’s, and Amyloidosis Program, Simmons Comprehensive Cancer Center, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX; Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL; Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY; Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT; Atrium Health Levine Cancer Institute, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Charlotte, NC; University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS; Abramson Cancer Center and Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, NY; Duke University Cancer Institute, Durham, NC; and Mayo Clinic, Division of Hematology, Rochester, MN; all in the USA). Given the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived or not required by the respective IRBs in accordance with applicable federal regulations and institutional policies. All data were handled in compliance with relevant privacy and confidentiality guidelines. All authors had access to the data and contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the results. The authors confirm the accuracy and completeness of the data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Afrough, A., Dima, D., Razzo, B. et al. The impact of extramedullary and paraskeletal plasmacytomas on treatment outcomes in multiple myeloma treated with teclistamab: U.S. Myeloma Immunotherapy Consortium real-world experience. Blood Cancer J. 16, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01414-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01414-6