Abstract

We examined the clinical course and risk factors for late onset neurotoxicities, including nerve palsies (IEC-NP) and parkinsonism (IEC-PKS), in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) treated with ciltacabtagene autoleucel (cilta-cel) in standard-of-care practice (SOC). Among 235 RRMM patients who received cilta-cel, 15 (6.4%) developed IEC-NP and 9 (3.8%) developed IEC-PKS with one patient developing both. Pre-infusion, patients with age >75 years, bone marrow plasma cells ≥20%, or involved free light chain ≥20 mg/dL had increased odds of IEC-PKS. Post-infusion, patients who developed ICANS, received higher cumulative steroid doses or received >1 dose of tocilizumab also had increased odds of IEC-PKS. High peak absolute lymphocyte count (ALCpeak) was a statistically significant predictor on univariate and multivariate analysis for IEC-NP and IEC-PKS. ALCpeak ≥ 3 × 109/L was identified as a meaningful threshold (AUC = 0.838) to predict for late onset neurotoxicity. An ALCpeak ≥ 3 × 109/L conferred a positive predictive value for delayed neurotoxicity of 31% vs a negative predictive value of 98% in patients with ALCpeak < 3 × 109/L. All IEC-NP patients received steroid +/- IVIG; 87% had complete resolution of their cranial neuropathies (median 57 days). Four patients with IEC-PKS received cyclophosphamide (1.5–2 g/m2) within 1-13 days of symptom onset and all had observable symptom improvement within 1–2 days.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Cilta-cel, CARVYKTI) is a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) targeting chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR-T) that is FDA approved for patients with relapsed, refractory multiple myeloma. While highly effective, uncommon but potentially devastating treatment-related delayed toxicities have been reported, including delayed neurotoxicity, such as immune-effector cell associated nerve palsies (IEC-NP) and Parkinsonism (IEC-PKS) [1]. These toxicities generally occur within one to six months post cilta-cel infusion and have been previously reported at an incidence rate of 5–10% and 2–5%, respectively [2,3,4,5] in clinical trials and standard-of-care (SOC) practice. IEC-NP, which predominantly affects the cranial nerves (facial nerve being the most common) can resolve with corticosteroids and/or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) treatment. However, a few rare exceptions, which include acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) and phrenic nerve palsy, have previously been reported [1, 5, 6]. Of note, post-hoc analysis of the CARTITUDE clinical trials has identified higher CAR-T cell expansion as a risk factor for IEC-NP [5]. Conversely, IEC-PKS, which presents with typical Parkinson’s disease-like features such as slow gait, flat affect, psychomotor retardation, bradykinesia with hypomimia, hypophonia, and postural instability, is generally non-responsive to systemic corticosteroids, follows a protracted course, and may be fatal in up to 50-60% of cases [7, 8]. Symptom onset occurs as early as the 3rd week from CAR-T infusion, independent from any cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and/or immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) episode [3]. Previously reported risk factors from the CARTITUDE-1 cohort include high tumor burden, high grade CRS or any grade ICANS together with high CAR T-cell expansion and persistence [3]. There is currently a paucity of studies examining risk factors and potential mitigating and management strategies in SOC practice. Herein, we aim to identify associated risk factors for these delayed neurotoxicities and describe current management strategies and outcomes using a Mayo Clinic SOC cohort.

Methods

Patient population

Medical records of patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma who received Cilta-cel as standard of care between 1st Feb 2022 to 31st Dec 2024 at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Florida and Arizona campuses were reviewed. CRS and ICANS were graded using American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) consensus criteria [9]. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Case definition, identification and clinical course description

Cases of delayed neurotoxicity (IEC-NP and IEC-PKS) among patients treated with cilta-cel between 1st Feb 2022 to 31st Dec 2024 were identified through a prospectively maintained IEC (immune effector cell) program compliance database. Both IEC-PKS and IEC-NP were diagnosed based on patient history, presenting symptoms and physical findings. Diagnosis was confirmed after assessment by neurologists at the respective Mayo Clinic campuses. Final description of neurologic course was centrally reviewed by A.Z.

CAR-T immunophenotype flow

EDTA-anticoagulated blood was lysed for RBC and stained with antibodies for lineage markers CD45 (clone 2D1, fluorochrome PO, Sysmex), CD3 (clone UCHT1, APC-750, Beckman Coulter), CD4 (clone 1338.2, APC, Beckman Coulter), CD8 (clone B9.11, APC-700, Beckman Coulter), and anti-VHH CAR (clone 96A3F5, PE, GenScript). Calibrated beads (Flow-Count Fluorospheres, Beckman Coulter, CAT #7547053) were added to the sample according to manufacturer’s instruction and analyzed by CytoFLex flow cytometer. Analysis was performed using Kaluza software version 2.3.

Statistical analysis

Differences in distributions of patient characteristics between delayed neurotoxicity (cases) and no toxicity groups (controls) were tested using the nonparametric Wilcoxon Rank-sum test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Patients with insufficient data, those who died within 30 days of cilta-cel or had less than 30 days of follow up were excluded from the risk factor analysis. Univariate logistic regression was used to identify potential factors associated with increased odds of delayed onset neurotoxicity. Multivariable models were constructed to determine if predictors of interest when examined concurrently, were still associated with delayed neurotoxicity. Variables that were statistically significant in univariable analyses were included in the multivariable model. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to identify appropriate cut-points for continuous variables using Youden index. This was subsequently used in logistic regression analyses for odds ratio calculation. For all ROC analyses, the outcome measure was development of any delayed neurotoxicity (IEC-PKS or IEC-NP). Statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP®, Version 18. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2023.

Results

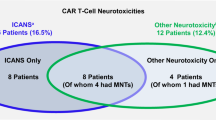

Incidence of IEC-NP and IEC-PKS

Between 1st February 2022 and 31st December 2024, 235 patients were treated with cilta-cel across the 3 Mayo Clinic sites, among which 15 (6.4%) developed IEC-NP and 9 (3.8%) developed IEC-PKS. One patient developed both.

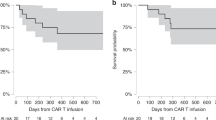

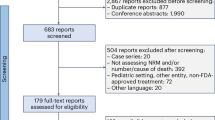

Baseline characteristics of the entire cohort

Of the 235 patients who received SOC Cilta-cel, 174 had complete data available. Final risk factor analysis included 169 patients after exclusion for early death before 30 days (n = 1) and other non-neurologic late toxicities (n = 4 with IEC-enterocolitis without delayed neurotoxicity, Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of the whole cohort are summarized in Table 1. Overall response rate of the final analysis cohort was 95% (160/169 patients) with 84% (142/169 patients) achieving a deep response (very good partial response or better). At a median follow up of 11.7 months (95% CI 9.0–13.6), thirty-four patients had either progressed or died and 12-month PFS was 81% (SE 3.52). There were no significant differences in the ORR (100% vs 95%, p = 0.60), deep response rate (96% vs 82%, p = 0.13) or PFS between the IEC-neurotoxicity and control cohorts (12-month PFS 84% vs 81%, p = 0.72). Of the twenty-two patients who died, eight were from disease progression, six from infection, three from delayed neurotoxicity (2 IEC-PKS, 1 IEC-AIDP), one from sudden cardiac arrest and four from non-specified causes. Non-relapse mortality rate was 17% (4/19) in patients with delayed neurotoxicity and 6.9% (10/146) in the control cohorts (p = 0.10).

CONSORT diagram of cohort (Created in https://BioRender.com).

IEC-nerve Palsy and associated risk factors

Fifteen patients developed IEC-NP. These included eleven patients with isolated facial nerve palsy (three bilateral and eight unilateral) and one with bilateral abducens nerve palsy. One patient (patient 15) developed concurrent IEC-PKS. A second patient (patient 9) developed sequentially orthopnea with bilateral phrenic nerve palsies on day 8 post infusion (without pain or other signs of plexopathy) followed by a pupil-sparing oculomotor nerve palsy (day 39) and a facial nerve palsy (day 46). A third patient (patient 11) had multiple cranial nerve (oculomotor, trigeminal, abducens and bilateral facial) involvement as well as electrodiagnostic evidence of a severe diffuse axonal polyradiculoneuropathy affecting upper and lower extremities, and a dorsal column tractopathy and limit-low levels of vitamin B12. Finally, a patient (patient 12) presented with unilateral facial nerve palsy on day 24 post infusion, followed 1.5 months later by a complex neurological presentation affecting upper and lower extremities with a chronic predominant axonal, sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy and superimposed radiculopathies (possible polyradiculoneuropathy) as well as possible post-synaptic neuromuscular junction disorder and compressive myelopathy. Nine of the fifteen patients with cranial nerve palsy had a brain MRI of which four (44%) had enhancement of the affected nerve.

The median time to onset of IEC-NP was 21 days (range 7–91). Of note, the patient who developed concurrent IEC-PKS and was not included in the pair-wise analysis for IEC-NP. Risk factor analysis compared characteristics between 14 patients with IEC-NP against 146 patients without delayed toxicities (controls, Tables 1, 2, Supplemental Table 1).

At evaluation, patients with IEC-NP had lower rates of prior autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) when compared to the controls (64% vs 88%, p = 0.027). At time of lymphodepletion, patients with IEC-NP had significantly lower median involved free light chain value compared to the controls (median FLC 0.94 vs 6.9 mg/dL, p = 0.0073). However, there were no observable differences in M-protein level, bone marrow plasma cell burden or rates of extramedullary involvement. Post-infusion, patients with IEC-NP also had a higher peak absolute lymphocyte count (ALCpeak) (median 5.3 vs 1.8 × 109/L, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2C). No differences in peak CRP (C-reactive protein), peak serum ferritin (supplemental Table 1), rates of CRS, ICANS, IEC-HS and patterns of corticosteroid or tocilizumab usage were seen in IEC-NP cases compared to the controls.

Serum Ferritin, CRP and ALC (median, interquartile range) expansion from cilta-cel infusion to 28 days of the controls, IEC-NP and IEC-PKS groups are plotted in (A) and calculated as area under the curve for 28 days (AUC28) and shown in (B). C Comparisons of ALC at different time points in patients with IEC-NP and IEC-PKS vs controls. D CAR+ cells are plotted versus lymphocyte count in samples collected at 2nd week after CAR-T infusion. E Comparisons of serum ferritin at different time points in patients with IEC-NP and IEC-PKS vs controls. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

IEC-Parkinsonism and associated factors

Nine patients developed IEC-PKS. The median time to onset of symptoms from CAR-T infusion was 24 days (range 15-96). One patient with IEC-PKS developed concurrent facial nerve palsy. All patients presented with hypomimia and in most, different degrees and presentations of frontal involvement were documented, including apathy, bradyphrenia, echolalia and decreased decision making (supplemental Table 2). All patients had some degree of axial and bilateral appendicular extrapyramidal involvement, presenting with rigidity and bradykinesia; all but three patients had symmetric involvement. Five patients also had appendicular tremor; tremor characteristics varied including resting, postural and kinetic tremor. No patients complained of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD) symptoms. Only one had documented orthostatic hypotension. At neurological nadir, all patients had a Hoen and Yahr scale score of at least 3 (5 being the most severe), except for one patient (patient 7) with mild presentation (Hoen and Yahr score = 2) [10]. At neurological nadir, median modified Rankin score was 3 (range 2-6) [11]. Eight patients underwent brain MRI at time of diagnosis of which six (75%) had a normal result. Two patients had basal ganglia T1 hyperintensities (supplemental Fig. 1). One of them also had faint gadolinium enhancement that persisted in a repeat MRI 3 months later, after the patient had received steroids and carbidopa/levodopa with improvement but persistence of her Parkinsonian syndrome. Cerebral spinal fluid analysis was performed in four patients (median time from symptom onset to CSF analysis 53 days, [range 1-183]) of which two (50%) had elevated white cells (range 19–33 cells/microL), which were predominantly lymphocytes ( > 90%). Three (75%) patients had elevated CSF protein (range 48–72 mg/dL). Infectious CSF testing and neural antibody testing were negative.

For identification of associated factors, comparisons were made between the 9 cases of IEC-PKS and the same 146 patient controls used in the IEC-NP analysis. Details of variables at time of evaluation and pre-lymphodepletion are shown in Table 1. There was a higher proportion of patients over 75 years old in the IEC-PKS group vs those with no delayed neurotoxicity (56% vs 5%, p = 0.0011). At time of lymphodepletion, patients with IEC-PKS had higher bone marrow plasma cell (BMPC) burden compared to the control group (median BMPC 25% vs 4%, p = 0.03).

Details of post-infusion variables are presented in Table 2. When comparing patients who developed IEC-PKS against the control group, there were no differences in the rates of CRS and rates of high-grade CRS ( ≥ grade 2). Rate of ICANS was higher in patients with IEC-PKS (33% vs 8%, p = 0.036). Patients with IEC-PKS had a higher rate of systemic corticosteroid use (89% vs 44%, p = 0.0163). They also had longer duration of corticosteroid use (median 4 vs 1 days, p = 0.0006) and higher cumulative corticosteroid doses (median 55 vs 10 mg dexamethasone or equivalent, p = 0.04 prior to ALCpeak (Table 2). Although there was no difference in the rate of tocilizumab usage (100% vs 85%, p = 0.11), patients with IEC-PKS had a higher rate of repeated ( > 1) tocilizumab use (100% vs 30%, P < 0.0001). There were no differences in the rates of IEC-HS and the use of anakinra. Patients with IEC-PKS also had a higher median ALCpeak (11.1 vs 1.8 × 109/L, p < 0.0001) and higher median day 28 ALC (Fig. 2C). Patients with IEC-PKS also had higher peak (median 1922 vs 652, p = 0.04) and day 28 serum ferritin level (median 628 vs 198 mcg/L, p = 0.04) (Fig. 2E).

High peak absolute lymphocyte expansion correlates with development of delayed neurotoxicities

CRP, serum ferritin and ALC were compared in the IEC-NP and IEC-PKS cohorts against the controls post CAR-T infusion for one month and at month 3 (Fig. 2A-C). CRP peak trended prior to ALCpeak, but were not statistically different among the groups, with median time to CRP peak for controls, IEC-NP and IEC-PKS at 8, 7.5 and 7 days, respectively (p = 0.24, supplemental Table 1). Serum ferritin started to rise at day 7 in all groups (Fig. 2A) and peaked at a median of 9 days (IQR 8–11). Quantifying serum ferritin levels over time for 28 days post CAR-T infusion (AUC28), patients with IEC-PKS had a higher median AUC28 compared to the controls (Fig. 2B). ALC expansion began after day 8 and peaked at a median of 12 days (IQR 11-13) after infusion (Fig. 2A). The median time to ALCpeak among patients with no delayed toxicity was 12 days (IQR 11-13) after CAR-T infusion. This was not significantly different compared to patients with IEC-NP (12 days, IQR 11–13, p = 0.58) and IEC-PKS (13 days, IQR 11–13.5, p = 0.45). The controls with no toxicity had a median ALCpeak of 1.82 × 109/L (IQR 0.97–4.05) which was significantly lower than patients with IEC-NP (5.33 ×109/L, IQR 3.36–10.97, p = 0.0008) and IEC-PKS (11.1 × 109/L, IQR 7.83–15.3, p < 0.0001, Fig. 2C). ALC at 1 month was higher in patients with IEC-PKS than in those with no delayed toxicity. Comparing total ALC expansion in the first month post cilta-cel infusion (area under the curve, AUC for day 0–28), median AUC28 was significantly higher in patients with IEC-NP compared to the controls (29.6 vs 20.7 AUC28, p = 0.03) and in those with IEC-PKS compared to the controls (67.8 vs 20.7 AUC28, p = 0.0014) (Fig. 2B). There was no statistically significant difference in ALC at 3 months between patients with IEC-PKS, IEC-NP and patients with no delayed toxicity (Fig. 2C).

To confirm that ALC can be a clinically accessible surrogate for CAR-T expansion, we compared CAR + T cells with ALC at day 14 (Fig. 2D). Indeed, lymphocyte count correlated with CAR + T cells (R = 0.9815, p < 0.0001).

To determine an ALCpeak threshold that would delineate risk for delayed neurotoxicity, an ROC analysis identified ALCpeak ≥ 3 × 109/L as a meaningful threshold value (AUC = 0.838). This is also the upper limit of normal for Mayo Clinic lab. Patients with ALCpeak ≥ 3.0 × 109/L had increased odds of developing any delayed neurotoxicity (OR 14.0; 95% CI 4.5-61.7), IEC-PKS (OR 16.9; 3.0–317.2) and IEC-NP (OR 12.6; 3.3–83.3). Using this threshold as a predictor for any delayed neurotoxicity yielded a positive predictive value (PPV) of 31% for ALCpeak ≥ 3 × 109/L compared to a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98% in those ALCpeak < 3.0 × 109/L (Table 3). PPV for IEC-NP was 21% in patients with ALCpeak ≥ 3 × 109/L and NPV was 99% in those ALCpeak < 3.0 × 109/L. PPV for IEC-PKS was 12% in those with ALCpeak ≥ 3 × 109/L and NPV was 99% in those with ALCpeak < 3.0 × 109/L.

We next limited the comparisons of post-infusion characteristics to controls with ALCpeak ≥ 3 × 109/L. Whilst no differences were seen between patients with IEC-NP and the controls, patients with IEC-PKS had a longer duration of CRS (median 3 vs 1 days, p = 0.028) and a higher rate of repeated ( > 1) tocilizumab use (100% vs 40%, p = 0.0018) (see Table 2).

Multivariate analysis for IEC-nerve palsy risk factors

On interrogation of baseline factors, patients with involved serum FLC < 20.0 mg/dL (OR 6.0, 95% CI 1.1–111.0) and no prior autologous stem cell transplant (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.2–13.8) appeared to have increased odds to develop IEC-NP. Full univariate logistic regression analysis is shown in supplemental Table 3.

Post-infusion, patients who had ALCpeak of ≥3.0 × 109/L had increased odds of developing IEC-NP (OR 27.4, 95% CI 5.2–504.6). After multivariate analysis, all three risk factors retained statistical significance suggesting independence of each other. Adjusted OR for ALCpeak of ≥3.0 ×109/L was 6.78 (4.6–935.1).

Multivariate analysis for IEC-Parkinsonism risk factors

Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine potential factors associated with IEC-PKS and shown in Fig. 3 (supplemental Table 3for full analysis). Our analysis showed an association between IEC-PKS and older age (>75 years), increased tumor burden (bone marrow plasma cells >20% or involved FLC > 20.0 mg/dL), development of ICANS, use of ≥2 doses of tocilizumab, ≥20 mg cumulative dose of dexamethasone or equivalent, elevated pre- and post-infusion ferritin and post-infusion peak ALC of above ≥3 × 109/L (Fig. 3). Of note, patients who had ALCpeak of ≥3.0 × 109/L had increased odds of developing IEC-PKS (OR 16.9, 95% CI 3.0–317.2). We next included all significant variables seen on univariate analysis in our multivariate model. On multivariate analysis, ALCpeak ≥ 3 ×109/L and the use of ≥2 tocilizumab doses remained the only two independent significant variables.

Key: ALC: absolute lymphocyte count; BM: bone marrow; CI: confidence interval; ICANS: immune-effector cell associated neurotoxicity syndrome; IEC-HS: immune effector cell associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like syndrome; IEC-PKS: immune effector cell associated parkinsonism; LC: light chains.

Management and outcomes of IEC-nerve palsy

Fourteen (94%) patients received systemic or oral corticosteroid treatment; twelve had prednisolone equivalent dose of 1–2 mg/kg and two with 1 gram of methylprednisolone for a total of 5–7 days followed by a steroid taper (Fig. 4A). Median time from symptom onset to treatment initiation was 1 day (range 0–5) and median duration of steroid taper was 12 days (range 6–83). One patient was managed by close observation and antiviral therapy alone. At the time of analysis, fourteen (93%) patients had complete resolution of symptoms. Median time to complete resolution from start of therapy was 57 days (range 8–253).

A Timing of toxicities and treatment in patients with IEC-NP. B Timing of toxicities and treatment in patients with IEC-PKS. CRS cytokine release syndrome, ICANS immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome, IEC-NP immune effector cell-associated nerve palsies, IEC-PKS immune effector cell-associated parkinsonism, IVIG intravenous immunoglobulin. CRS (purple bars), ICANS (blue bars), duration with delayed neurotoxicity symptoms (green bars), duration without toxicity (white bars), corticosteroid treatment (yellow triangle), IVIG treatment (yellow diamond in (A)), cyclophosphamide treatment (yellow diamond in (B)), carvidopa/levadopa (yellow square), death (black cross), alive at last follow-up (red circle).

All patients with IEC-NP and further neurological involvement described above received additional treatment. The patient (patient 9) with bilateral phrenic nerve palsy and multiple cranial neuropathies received IVIG and high dose steroids, including an extended 6-week course of weekly methylprednisolone after the cranial nerve presentations. At 260 days of follow up, the patient had ongoing symptoms. The patient (patient 11) with the facial neuropathy, axonal neuropathy, compressive myelopathy and possible myasthenic syndrome received IVIG, plasmapheresis and methylprednisolone but died from neurological complications 189 days after symptom onset. The patient (patient 12) with the severe axonal polyradiculoneuropathy, multiple cranial neuropathies and dorsal column tractopathy, received IVIG, plasmapheresis and methylprednisolone and was improving at 365 days of follow up. Finally, the patient (patient 15) with concurrent IEC-PKS received high dose methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide and IVIG within 5 days of presentation. His cranial nerve palsy was largely resolved at 45 days with improvement of his IEC-PKS symptoms. Two patients with IEC-NP went on to develop IEC-enterocolitis.

Management and outcomes of IEC-Parkinsonism

Management strategies for IEC-PKS included steroids, cyclophosphamide and dopamine replacement therapy (carbidopa/levodopa, Fig. 4B). Median follow-up time from symptom onset was 3.4 months (range 2.1–13.2). At the time of analysis, three patients (patients 1, 6 and 8) had received a course of systemic steroids +/- dopamine replacement therapy; of these, two had symptom improvement starting at 1 and 6 months with symptoms yet to fully resolve at 3 and 13 months, respectively. The other one died from IEC-PKS related complications. Four (patients 3, 4, 5 and 9) had received cyclophosphamide (1.5–2 g/m2) within 1–13 days of symptom onset +/- dopamine replacement therapy; all had symptom improvement with 1–2 days. All four were alive and continue to improve at the time of last follow up (range 2.6–4.3 months from cyclophosphamide). Two patients did not receive any intervention (patients 2 and 7) of which one had resolution over 2 months and one died 3 months after symptom onset from IEC-PKS related complications. The patient (patient 7) with spontaneous resolution, presented with minor symptoms mainly consisting of hypomimia, bradyprenia and reduced arm swing (Hoen and Yahr score = 2). Of note, three patients subsequently went on to develop IEC-enterocolitis.

Based on the collective experiences of our neurologist and myeloma CAR-T MDs, we have developed an expert opinion guideline for evaluation and management of IEC-neurotoxicities on mSMART.org (Fig. 5) [12].

Discussion

Cilta-cel demonstrates unprecedented efficacy in the treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma from the registration studies CARTITUDE-1 and -4 and has replicated the transformative potential of this therapy in real-world reports [2, 13, 14]. Although uncommon, delayed neurotoxicity, when it occurs, may follow a protracted course and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Some mitigating strategies were identified during the clinical trials, including reducing myeloma disease burden prior to CAR-T infusion and early intervention to reduce the severity of CRS [3]. In subsequent clinical trials, these appear to have reduced the incidence of late neurotoxicities. However, given that SOC practice treats a broader demographic of patients and adequate reduction of disease burden may not always be possible for patients in later lines of therapy, identification of risk factors may help with the development of additional mitigating strategies.

In a recent real-world study by Sidana et al., any-grade ICANS and steroid use were identified as risk factors for any delayed neurotoxicity [4]. In addition, a post-hoc analysis from the CARTITUDE-1 cohort with 5 documented cases (5%) of IEC-PKS (then called movement and neurocognitive treatment-emergent adverse events), demonstrated that high tumor burden, high grade CRS and similarly, any grade ICANS was associative [3]. Relative to the CARTITUDE-1 cohort, our cohort contained a less heavily pre-treated population (median 4 prior lines) with a lower proportion of patients (<10%) with high tumor burden. Even so, we similarly demonstrated in our analysis that higher bone marrow plasmacytosis and involved free light chain burden are associated with increased risk of IEC-PKS. Although the development of CRS ≥ grade 2 was not associated with IEC-PKS in our cohort, this is likely reflective of earlier intervention for CRS. Association of higher inflammatory state with IEC-PKS is reflected by the longer duration of CRS and higher proportion of patients receiving more than 1 dose of tocilizumab for management of CRS. ICANS was also an identified risk factor, similar to the CARTITUDE-1 analysis. Of note, older age (>75 years) appears to be a risk factor for IEC-PKS which was not previously demonstrated. So far, no risk factors have been identified for isolated cases of IEC-NP. In our IEC-NP cohort, we observed lower rates of prior ASCT treatment in the absence of any age differences, suggesting that the impact of prior lines of therapy may shape a patient’s immune and CAR-T profile [15]. Prior data have also shown that prior ASCT may be associated with shorter PFS and lower CAR-T efficacy, suggesting potential impact of ASCT on subsequent immune cell composition, impacting CAR-T outcome [16]. ALCpeak aside, risk factors identified in IEC-PKS were not replicated in IEC-NP, which possibly suggests a different underlying pathophysiology for the development of these two toxicities.

Early and rapid CAR-T expansion has been correlated to the occurrence and severity of ICANS [17]. Patients with IEC-PKS also have shown high CAR-T peak expansion [3]. However, measurement of circulating CAR transgene levels is not readily available and not a clinically validated test. In contrast, ALC measurement is a simple, readily available and routinely performed in SOC practice. Mejia Saldarriaga et al. further concluded based on flow cytometric findings that the early lymphocytosis seen in week 2-3 after CART infusion was predominantly driven by BCMA CAR-T cells, with ALC comprising of >50% of T-lymphocytes on day 14, confirming ALC as an appropriate surrogate for CAR-T expansion [18], which was also confirmed in our analysis here. Analysis from CARTITUDE-1 showed that high ALC on Days 14, 21, and 28 post cilta-cel infusion was associated with IEC-PKS [3]. In our data set, serial ALC was readily available for all patients, and we clearly demonstrate that peak ALC occurs between the 2nd and 3rd week after CAR-T infusion. We found that an ALCpeak ≥ 3.0 × 109/L was associated with a significantly higher risk for delayed neurotoxicities (31%; IEC-PKS, 12% and IEC-NP, 21%) compared to only 2% in patients with peak ALC of <3.0 ×109/L, consistent with a high negative predictive value using this threshold.

As such, intervention at the time of ALCpeak, which usually lags behind the onset of CRS could be considered as additional potential risk mitigation strategy. Earlier this year, Turner et al. reported that ALC expansion predicted for severe early toxicity (including neurotoxicity) and risk of death [19]. In addition, limited use of corticosteroid with and without tocilizumab during management of CRS and ICANS has not been found to negatively impact clinical response or PFS in the CD19 CAR-T space [20]. An intervention of 6 doses of 10 mg of dexamethasone given over 3 days (in a 40 mg, 20 mg,10 mg dosing schedule) was reported for patients who had a peak ALC > 5 × 109/L. In that report, the use of dexamethasone as prophylaxis allowed for the blunting and subsequent decrease of ALC expansion [19]. In addition, in cases where continued ALC expansion is observed despite the antecedent use of corticosteroids, therapies such as cyclophosphamide can be considered. Noting that corticosteroids or lymphotoxic drugs (i.e. cyclophosphamide) impact lymphocyte expansion and function differently, their mechanisms of action on CAR-T function and their individual impact on mitigating risk of delayed neurotoxicity requires formal study. It is also important to note that not all patients with high ALCpeak develop delayed neurotoxicity. This suggests other factors in play, possibly the expansion of specific activated T cell phenotypes or autoimmune activation. Future studies with detailed immune profiling on a large case cohort are needed to clarify these risks and identify markers for susceptibility.

Previous attempts have been made to elucidate the pathophysiology of IEC-PKS to guide potential intervention. Imaging findings mainly show non-specific MRI changes in the brain, even though cases have been described with FLAIR/T2 basal ganglia hyperintensities [21]. In our cohort, two patients had T1 basal ganglia hyperintensities, one with faint gadolinium enhancement. Brain FDG-PET scans have demonstrated hypometabolism in the basal ganglia but also the frontal lobes [3, 7, 8]. The patients in our cohort presented with extrapyramidal signs but also prominent clinical frontal involvement corresponding to the PET abnormalities reported previously. Autopsy findings of patients with IEC-PKS further demonstrated focal gliosis and T-cell infiltrate skewed towards CD8 + T-cells in the basal ganglia with the substantia nigra appearing to be unaffected [8]. BCMA expression was demonstrated in neurons and astrocytes in the caudate nucleus and the adjacent frontal cortex of the affected patients; transcriptomic databases also suggest basal ganglia BCMA RNA expression in normal individuals [8]. All these point towards a pathological process distinct from Parkinson’s disease which explains minimal to modest response to dopamine replacement therapy in our patients, similarly seen in other case reports [3, 7, 8]. Correlative studies have, however, demonstrated the persistence of circulating CAR-T cells with an effector memory phenotype in IEC-PKS cases which points to the possible role of lymphodepleting or modulatory agents [8]. The use of high systemic doses of corticosteroids during IEC-PKS in our cohort had mixed results whilst the use of the lymphotoxic agent cyclophosphamide early at the time of symptom onset at doses between (1.5–2 g/m2) have shown the most promise with early recovery demonstrated in a few case series [7, 22, 23]. Improvement of clinical symptoms within 0.5 to 2 days were evident in the four patients who received cyclophosphamide within 1–13 days of symptom onset in our cohort. Symptom improvement also continued over several months. Further follow up is required to determine the time to symptom resolution with this intervention. A drawback to this strategy is that high dose chemotherapy can be associated with increased risk of infection, and more rigorous infection surveillance and extended antimicrobial prophylaxis should be considered. In addition, the potential impact of high dose chemotherapy on durability of CAR-T response remains to be seen and requires longer follow-up. Notably, in our IEC-NP and IEC-PKS cohorts, all had achieved BM MRDneg response at the time of their neurologic symptoms and only one patient (who did not receive cyclophosphamide) had relapsed after 9 months. A further four had died from non-relapse related causes of which three (2 with IEC-PKS and 1 with IEC-NP) from complications related to their delayed neurotoxicity. Given the high mortality rate for patients with severe IEC-PKS, it is important that we continue to elucidate pre-disposing risk factors and the optimal timing and agents for intervention.

Management and diagnosis of 21 cases with IEC-NP from the CARTITUDE trials have been previously presented with response to treatment similar to our cohort [5]. It was also noted that cases of IEC-PKS and IEC-NP did not often overlap suggesting two different pathogenic processes. However, cases of both delayed neurotoxicities have been described, including one patient from our cohort [24]. Like the CARTITUDE trials, a proportion of our IEC-NP patients with facial nerve palsy demonstrated facial nerve enhancement of MRI and our cases were treated and responded similarly (2-week course of corticosteroids, including taper, with a 2–3 month recovery time). IVIG was also used in a proportion of patients (with additional neurological involvement) at diagnosis similar to other reported cohorts [25]. The impact of corticosteroid treatment and IVIG on the disease course of IEC-NP is still uncertain but most patients have a favorable outcome. It is, however, important to highlight that IEC-NP do not only affect the cranial nerves and three of our patients developed multifocal neurological presentations, highlighting the importance of monitoring these potentially fatal toxicities up to 3 months post CART. Based on currently available literature and experience, Mayo Clinic has provided mSMART recommendations based on the expert opinions from the Mayo Clinic dysproteinemia group, and collaborating neurologists, for the evaluation and management of IEC-associated delayed neurotoxicities [12].

It is also important to note that no IEC-NP or IEC-PKS have been reported on preliminary results from BCMA-targeting anitocabtagene autoleucel (anito-cel). This CAR construct utilizes a novel D-domain binding component which allows for quick release of the CAR-T cells from their BCMA target, potentially decreasing these cells’ reactivity to BCMA in the CNS [26, 27] and is certainly a developing area of interest.

The main limitations of our study include its single center design and small number of neurotoxicity cases limiting generalizability and statistical power. Intervention strategies among the small number of cases were also heterogenous owing to lack of initial consensus guidelines disallowing any strong conclusions to be drawn. In addition, whilst we focused on the motor aspects of these neurotoxicities, there are clear neurocognitive sequelae that are still underexplored. As such, future multi-institutional collaborative efforts in validating our findings on associated factors, finding consensus in diagnosis and severity grading and standardizing management are imperative.

Conclusion

Increased tumor burden and advanced age may be associated with increased risk for IEC-PKS highlighting the importance for careful patient selection and effective bridging therapy prior to CART therapy. Pre-treatment predictors for IEC-NP are still, however, yet to be determined. Post CART infusion peak ALC may predict the risk for delayed neurotoxicity suggesting that CART over-expansion may be a predisposing factor for IEC-PKS and to a lesser extent IEC-NP. This is despite higher prior cumulative steroid and tocilizumab doses and also reflective of an inflammatory process more refractory to current management practices for CRS. To blunt peak ALC expansion, different early mitigating strategies including dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide are being tried in SOC practice. The early use of high dose cyclophosphamide appears to induce early symptom improvement in IEC-PKS and should be considered at time of symptom onset. Since these symptoms may develop when patients have returned home from CAR-T treatment centers, education of patients, caregiver, and home primary hematologist/oncologist for early symptom identification is critical. As our understanding for management is still evolving, ongoing communication with the CAR-T center for the most updated evaluation and management practices is key and ensures the best possible patient outcome.

Ethics approval, consent to participate and inclusion statement

The study received approval from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (16-008261). All procedures adhered to applicable guidelines and regulations, and given the retrospective nature of this research, patient informed consent was not required.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Ellithi M, Elsallab M, Lunning MA, Holstein SA, Sharma S, Trinh JQ, et al. Neurotoxicity and rare adverse events in BCMA-directed CAR T cell therapy: a comprehensive analysis of real-world FAERS data. Transplant Cell Ther. 2025;31:71. e1–e14.

San-Miguel J, Dhakal B, Yong K, Spencer A, Anguille S, Mateos M-V, et al. Cilta-cel or standard care in lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:335–47.

Cohen AD, Parekh S, Santomasso BD, Gállego Pérez-Larraya J, van de Donk NW, Arnulf B, et al. Incidence and management of CAR-T neurotoxicity in patients with multiple myeloma treated with ciltacabtagene autoleucel in CARTITUDE studies. Blood Cancer J. 2022;12:32.

Sidana S, Patel KK, Peres LC, Bansal R, Kocoglu MH, Shune L, et al. Safety and efficacy of standard-of-care ciltacabtagene autoleucel for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2025;145:85–97.

Van De Donk NWCJ, Sidana S, Schecter JM, Jackson CC, Lendvai N, De Braganca KC, et al. Clinical experience with cranial nerve impairment in the CARTITUDE-1, CARTITUDE-2 Cohorts A, B, and C, and cartitude-4 studies of ciltacabtagene autoleucel (Cilta-cel). Blood. 2023;142:3501.

Fitzgerald EC, Gilbert DL, Tanner A, Lin Y, Gupta S. Orthopnea from phrenic nerve palsy after ciltacabtagene autoleucel CAR-T in a patient with multiple myeloma. Transplant Cell Ther. 2025;31:S503.

Karschnia P, Miller KC, Yee AJ, Rejeski K, Johnson PC, Raje N, et al. Neurologic toxicities following adoptive immunotherapy with BCMA-directed CAR T cells. Blood. 2023;142:1243–8.

Van Oekelen O, Aleman A, Upadhyaya B, Schnakenberg S, Madduri D, Gavane S, et al. Neurocognitive and hypokinetic movement disorder with features of Parkinsonism after BCMA-targeting CAR-T cell therapy. Nat Med. 2021;27:2099–103.

Lee DW, Santomasso BD, Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Turtle CJ, Brudno JN, et al. ASTCT consensus grading for cytokine release syndrome and neurologic toxicity associated with immune effector cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:625–38.

Goetz CG, Poewe W, Rascol O, Sampaio C, Stebbins GT, Counsell C, et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: status and recommendations the Movement Disorder Society Task Force on rating scales for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1020–8.

Banks JL, Marotta CA. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis. Stroke. 2007;38:1091–6.

mSMART. The Risk Adapted Approach to Management of Multiple Myeloma and Related Disorders: Management of CAR-T associated cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurotoxicity, and cytopenias [2025 Apr 04]. Available from: https://www.msmart.org/mm-treatment-guidelines.

Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Usmani SZ, Jakubowiak A, Agha M, Cohen AD, et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet. 2021;398:314–24.

Usmani SZ, Berdeja JG, Madduri D, Jakubowiak AJ, Agha ME, Cohen AD, et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA)-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy, in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (R/R MM): Updated results from CARTITUDE-1. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2021.

Paiva B, Manrique I, Thompson EG, Campbell TB, Guerrero C, Martin N, et al. Biological and clinical significance of endogenous and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell immune profiling in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) patients. Blood. 2024;144:900.

Gustine J, Cirstea D, Branagan AR, Yee AJ, Maus M, Frigault MJ, et al. Previous HDM/ASCT adversely impacts PFS with BCMA-Directed CAR T-Cell therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2024;144:79.

Holtzman NG, Xie H, Bentzen S, Kesari V, Bukhari A, El Chaer F, et al. Immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for lymphoma: predictive biomarkers and clinical outcomes. Neuro-Oncol. 2021;23:112–21.

Mejia Saldarriaga M, Pan D, Unkenholz C, Mouhieddine TH, Velez-Hernandez JE, Engles K, et al. Absolute lymphocyte count after BCMA CAR-T therapy is a predictor of response and outcomes in relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2024;8:3859–69.

Turner J, Forsberg PA, Nicholson S, Schade H, Matous J, Gregory TK. Prophylactic Dexamethasone Rescues Unrestrained Lymphocyte Expansion in Anti-BCMA Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy in Multiple Myeloma. Transplant Cell Ther, Off Publ Am Soc Transplant Cell Ther. 2025;31:S215–S6.

Topp MS, van Meerten T, Houot R, Minnema MC, Bouabdallah K, Lugtenburg PJ, et al. Earlier corticosteroid use for adverse event management in patients receiving axicabtagene ciloleucel for large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2021;195:388–98.

Gudera JA, Baehring JM, Fulbright RK, Dietrich J, Karschnia P. P12.10.b hypokinetic movement disorders following adoptive immunotherapy with BCMA-directed CAR T-cells: a consecutive case series. Neuro-Oncol. 2024;26:v68–v.

Blumenberg V, Puliafito BR, Graham CE, Leick MB, Chowdhury MR, King M, et al. Cyclophosphamide mitigates non-ICANS neurotoxicities following ciltacabtagene autoleucel treatment. Blood. 2025;145:2788–93.

Graham CE, Lee W-H, Wiggin HR, Supper VM, Leick MB, Birocchi F, et al. Chemotherapy-induced reversal of ciltacabtagene autoleucel–associated movement and neurocognitive toxicity. Blood. 2023;142:1248–52.

Wu AS, Hophing L, Gosse P, Motamed M, Bhella SD, Stewart K, et al. Parkinsonism and bilateral facial palsy after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2025;12:371–4.

Kumar AD, Atallah-Yunes SA, Rajeeve S, Abdelhak A, Hashmi H, Corraes A, et al. Delayed neurotoxicity after CAR-T in multiple myeloma: results from a global IMWG Registry. Blood. 2024;144:4758.

Frigault M, Rosenblatt J, Dhakal B, Raje N, Cook D, Gaballa MR, et al. Phase 1 study of CART-ddBCMA for the treatment of subjects with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2022;140:7439–40.

Bishop MR, Rosenblatt J, Dhakal B, Raje N, Cook D, Gaballa MR, et al. Phase 1 study of anitocabtagene autoleucel for the treatment of patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): efficacy and safety with 34-month median follow-up. Blood. 2024;144:4825.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Immune Effector Cell Compliance Program managers and data coordinators for sharing the CAR-T outcome data, and patients and family for participating in the study.

Funding

No relevant funding to disclose for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J.L., A.Z., Y.L.: Conceptualization, data curation, writing–original draft. K.J.L. performed the statistical analyses. R.P., S.C., K.D., A.D., D.C., M.G., L.H., H.S., P.K., M.T., T.K., R.W., J.C., M.B., P.L.B., U.Y., E.W., S.G., S.K., S.A., R.F., A.Z., Y.L.: Data curation, critical appraisal and writing-editing the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to acquisition of data, critically revised the manuscript, and gave final approval of the manuscript to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.D., A.D., D.C., L.H., H.S., P.K., M.T., T.K., R.W., J.C., M.B., U.Y., E.W., S.G.: no relevant disclosures; K.J.L.: Research funding from Sanofi; R.P.: advisory board role for Sanofi Aventis and Astra Zeneca, research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation and GlaxoSmithKline; S.C.: honoraria from Sanofi, Ascentage Pharma, Sobi, Legend Biotech, and research funding from Johnson & Johnson, Takeda, C4 Therapeutics, Abbvie, Ascentage Pharma, AstraZeneca; M.G.: personal fees from Ionis/Akcea, honorarium from Alnylym, personal fees from Prothena, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Janssen, personal fees for Data Safety Monitoring board from Abbvie & Arcellex, fees from Johnson & Johnson, Honoraria for Astra Zeneca, Medscape, Dava Oncology. Alexion; P.K.: Honoraria: Pharmacyclics, Sanofi, BeiGene, MustangBio, AstraZeneca, AbbVie. Consulting or Advisory Role: Sanofi. Research Funding: Amgen, Takeda, Sanofi, AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Sorrento Therapeutics, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Regeneron, Ichnos Sciences, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene; P.L.B.: Consultant: Oncopeptidfes. Salarius, Radmetrix, Omeros, CellCentric, AbbVie, Pfizer; S.K.: Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, Janssen Oncology, Genentech/Rocher, Abbvie, BMS/Celgene, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, K36 Therapeutics; travel, accommodation and expenses: Abbvie, Pfizer; Research funding: Takeda, Abbvie, Novartis, Sanofi, Janssen Oncology, MedImmune, Roche/Genentech, CARsgen Therapeutics, Allogene Therapeutics, GSK, Regeneron, BMS/Celgene; S.A.: Consulting or Advisory Role: Takeda, BeiGene, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Pharmacyclics, BMS, Amgen, Janssen, Regeneron, Cellectar. Research Funding: Pharmacyclics, Janssen Biotech, Cellectar, BMS, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, Ascentage Pharma, Sanofi; R.F.: consultancy for AbbVie, Adaptive, Amgen, Apple, BMS/Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, Pfizer, RA Capital, Regeneron, Sanofi. Scientific advisory board: Caris Life Sciences. Board of directors: Antengene. Patent for FISH in multiple myeloma. A.Z.: patents submitted for DACH1-IgG, PDE10A-IgG, CAMKV-IgG, Tenascin-R-IgG as biomarkers of neurological autoimmunity, received research funding from Roche/Genetech and Center for MS and Autoimmune Neurology at Mayo Clinic not relevant to this study, Consulted without personal compensation for Alexion pharmaceuticals, steering committee for the KYSA-8 study for autologous CAR-T-19 treatment for SPS; no personal compensation; Y.L.: advisory board role for Janssen, Sanofi, BMS, Regeneron, Genentech, Tessera, Legend, NexT Therapeutics, steering committee for Janssen, Kite/Gilead, research funding from Janssen, BMS, scientific advisory board for NexImmune, Caribou and data safety monitor board for Pfizer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, K.J.C., Tan, M., Parrondo, R. et al. Clinical course, risk factors and mitigating strategies for Immune effector cell-associated late onset neurotoxicities after ciltacabtagene autoleucel CAR-T in multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 16, 18 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01441-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-025-01441-3