Abstract

Transplantation of peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) from matched unrelated donors (MUD) is still associated with a significant risk for graft vs. host disease (GvHD), especially in pediatric patients receiving grafts from adult donors containing high amounts of T cells. Here, we present long-term follow-up results on 25 pediatric patients, (acute leukemia n = 15, NHL n = 3, CML n = 3, MDS n = 5), transplanted with CD34 or CD133 positively selected PBSC from MUDs supplemented with an add-back of 1 × 107/kg body weight (kgBW) unselected T cells resulting in a median T-cell depletion (TCD) of 1.97 log. A total of 24/25 (96%) patients had primary engraftment. Early T-cell recovery was significantly improved compared to patients receiving CD34-selected grafts without T-cell add-back and similar to patients receiving unmanipulated bone marrow. GvHD incidence was low with 8/4% aGvHD grade II/III, no grade IV and 13% limited cGvHD. In total, 16/25 (64%) patients are alive after a median follow-up of 10 years. Five-year event-free survival (EFS) was 68%, relapse probability 24% and transplantation-related mortality (TRM) 12%. Thus, in PBSC allotransplants from MUD, partial TCD with serotherapy and CSA/MTX prophylaxis, can effectively reduce GvHD without hampering engraftment and immune reconstitution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHSCT) from matched unrelated donors (MUD) has become a well-established and routinely performed treatment strategy in various malignant and non-malignant hematological disorders [1]. Early post-transplant T-cell recovery and function is likely to be beneficial in alloHSCT due to suppression of graft rejection, reduction of infectious complications and mediation of a graft-vs.-leukemia effect [2,3,4]. In contrast, subsets of donor T cells are essentially linked to the pathogenesis of graft-vs.-host disease (GvHD), which remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in alloHSCT [5,6,7]. The risk for GvHD is positively correlated with the amount of T cells infused [8,9,10,11]. Especially in the setting of young pediatric patients with low BW and adult MUDs, grafts with high numbers of stem cells may inevitably contain considerable numbers of T cells, potentially raising the risk for acute GvHD (aGvHD) and chronic GvHD (cGvHD). Several groups have shown that ex vivo T-cell depletion (TCD) can substantially reduce the incidence of GvHD in children [12,13,14]. However, this benefit was counterbalanced by an increased risk for graft failure, delayed immune reconstitution, and consecutively higher risk for life-threatening viral and fungal infections and malignant relapse [12, 13, 15,16,17]. In an attempt to counteract these shortcomings of TCD, add-backs of unselected CD3+ T cells at various dose levels have been transplanted with the graft, demonstrating improvements [14, 18]. However, important questions, such as the optimal dosage of T cells, whether immunosuppression should be used and how serotherapy might interfere, have not been resolved. Thus, we analyzed a cohort of pediatric patients receiving CD34 or CD133 positively selected hematopoietic stem cells with a defined add-back of 1 × 107/kgBW T cells from MUDs along with serotherapy (ATG-Fresenius) and CSA/MTX GvHD prophylaxis.

Patients and methods

All 25 pediatric patients who received transplants of purified CD34+ (n = 8) or CD133+ (n = 17) stem cells and a defined add-back of 1 × 107/kgBW CD3+ T cells from matched unrelated donors (MUD) were included. Patients receiving anti-CD34 or anti-CD133 positively selected grafts were merged for analysis, since both methods are very likely to enrich the same CD34+/CD133+ double-positive stem cell population. Neither CD34+/CD133− nor CD34−/CD133+ cells have been detected after enrichment [19]. Indications for transplantation are given in Table 1. Patients were considered for transplantation according to German ALL BFM 2000/2004, AML BFM, CML paed or EWOG-MDS treatment protocols. The study protocol was approved by the local ethical committees and by the German Federal Agency “Paul-Ehrlich-Institut”. Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians or patients. The primary endpoint of the study was immune recovery at day +90. Secondary endpoints were TRM and EFS at 1 year. At the University Children’s Hospital in Tuebingen, all patients (n = 20) receiving MUD grafts in the years 2001 to 2005 were treated in the study. At the University Children’s Hospital in Wuerzburg, the protocol was offered to patients receiving PBSC grafts from MUDs between 2007 and 2010 as a standard of care in order to reduce the risk of severe GvHD (n = 5). To evaluate the effect of the add-back strategy on T-cell reconstitution, immune recovery of the study group was compared to that of two historical controls cohorts. The 1st control group (ctrl. group deplete) consists of 31 patients transplanted with highly purified CD34+ selected stem cells within a clinical trial as previously published [12]. The 2nd control group (ctrl. group replete) consists of 22 patients receiving unmanipulated bone marrow (BM) grafts. All patients were transplanted between 1990 and 2002 at the University Children’s Hospital in Tuebingen. Distribution of diagnosis among the three groups was considered similar (lymphoid or myeloid malignancies or MDS RCC). Patient characteristics and graft compositions are given in Table 1.

Stem cell mobilization, purification of progenitor cells by CD34+ or CD133+ selection and graft composition

All donors agreed to donate peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC). Donors were matched for HLA-A/B (medium resolution typing) and DRB1/DQB1 (high resolution). PBSC were mobilized by 10 µg/kgBW G-CSF daily for 5 days and harvested by leukapheresis. In one patient, experiencing graft failure, a second donor was recruited. We sought to obtain 1 × 107 progenitors per kgBW. Selection of progenitors with anti-CD34 (n = 8) or anti-CD133 coated microbeads (n = 17) was carried out using the automated CliniMACS® device (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) as described previously [20]. Before and after separation, cell populations were stained with anti-CD34, antiCD133, antiCD3, antiCD19, and antiCD45 mAbs and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) on FACSCalibur™ instruments (Becton-Dickinson, Munich, Germany) according to the ISHAGE guidelines [21]. A median of 7 × 103/kgBW CD3+ T cells remained in the graft after enrichment. An unselected aliquot from the non-manipulated donor’s leukapheresis product containing 1 × 107/kgBW T cells was added to the purified stem cell graft before infusion into the patient.

Treatment protocol

Myeloablative conditioning regimens were based on either total body irradiation (TBI) (six fractions of 2 Gy each, n = 11), intravenous busulfan (Bu) (12.8 mg/kgBW for age > 3 years and 16 mg/kgBW for age < 3 years, n = 10) or treosulfan/melphalan (n = 2) with specific modifications according to the underlying treatment protocols, summarized in Table 2. Patients with MDS RCC received a non-myeloablative regimen (n = 4) consisting of fludarabine and thiotepa. Serotherapy with ATG F 40–60 mg/kgBW was administered in all patients. One patient experiencing graft rejection (CML, ATG, Bu, Cy), was re-conditioned with total lymphoid irradiation (7 Gy), thymoglobulin (6 mg/kgBW and fludarabine (160 mg/m2). Patients received G-CSF only in case of prolonged aplasia or infections for a short period of time (n = 14). Prophylactic post-transplant immunosuppression consisted of methotrexate (MTX) (10 mg/m2, on days +1, +3, and +6) and ciclosporin A (CSA) (3 mg/kgBW, adjusted to blood levels 80–120 µg/l) starting day −2 until day +100. Supportive care was carried out as previously described [12]. In ctrl. group deplete, no post-transplant immunosuppression was applied. Patients in ctrl. group replete received the same prophylactic post-transplant immunosuppression as the study group. Serotherapy with ATG F 40–60 mg/kgBW was administered in all groups at days −4, −3, and −2.

Assessment of engraftment, chimerism, and immune reconstitution

The day of engraftment was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days on which the absolute leukocyte count (ALC) was >1 × 109/l. Chimerism was assessed weekly in peripheral blood samples until day +100 followed by 3 month intervals. Reconstitution of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, CD19+, and CD56+ lymphocytes was monitored weekly by FACS analysis until T-cell recovery began and was subsequently assessed every 3 months.

Statistical analysis

The probability of EFS, defined as survival without evidence of persistence or relapse of the underlying disease at any time post-transplant, was estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier. Cumulative incidence of aGvHD, relapse and TRM was calculated considering competing risks after Gooley at al. [22, 23]. Numbers of competing events consider were 4 for aGvHD, 4 for relapse and 6 for TRM. Unpaired t-test was used to compare T-cell reconstitution, in the study and control groups. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute), and PRISM 7 (Graph-Pad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Graft composition

Patients received a median of 1 × 107/kgBW CD34+ or CD133+ purified CD34+ progenitor cells (range 0.45 to 3 × 107/kgWB cells). The median purity after separation was 98.0%, with a viability >95%. A product with a defined add-back of CD3+ T cells to a fixed intended number of 1 × 107/kgBW was infused in all patients (Fig. 1). The final median TCD efficacy was 1.97 log (range 0.8 to 4.8 log).

Engraftment and donor chimerism

Initial engraftment occurred in 24 out of 25 patients. The median time to an ALC > 1 × 109/l without G-CSF stimulation was 18 days (range 12 to 30 days; n = 11 patients). Patients who received G-CSF (5 µg/kgBW) had a median ALC > 1 × 109/l at 28 days (range 13 to 40 days; n = 13 patients). In total, 24 out of 25 patients showed sustained engraftment after initial transplantation. One patient experiencing graft rejection was re-transplanted with 2.14 × 107/kgBW CD34+ purified progenitor and 1 × 107/kgBW CD3+ T cells from a different MUD, reaching an ANC > 1 × 109/l at day +9 and a sustained engraftment thereafter. Thus, all patients finally engrafted (Table 3). At day +100, 23 out of 25 patients were alive, achieving complete donor chimerism in 22 (96%) and stable mixed chimerism (20–30% autologous proportion) in 1 CML patient.

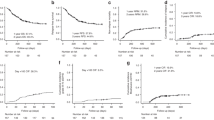

Platelet recovery and immune reconstitution

The median time to platelet recovery, defined as the time to reach independence from substitution, was 16 days (range 9 to 87 days). Recovery of major immune cell subsets is illustrated in Figure 2a. CD56+ NK cell recovery was rapid with a clear peak around day +30 and a mean number of 289 cells/µl (range 1 to 909 cells/µl). B-cell recovery was acceptable. No sustained deficiency of CD19+ cells was observed. Beginning at day +60, patients with T-cell add-back showed a significantly improved T-cell recovery compared to T-cell deplete grafts with mean CD3+ T cells counts of 253 vs. 56 cells/μl (p = 0.009), mean CD3+CD4+ counts of 59 vs. 10 cells/μl (p = < 0.0001) and mean CD3+CD8+ counts of 184 vs. 27 cells/μl (p = 0.006). Significantly improved recovery was also seen at day +90 and day +180 for total CD3+ (p = 0.019 and p = 0.0009) as well as CD3+CD8+ T cells (p = 0.021 and p = 0.0006). CD3+ T cell counts of >100 cells/μl were achieved at a median of 56 days in the add-back group compared to 154 days in the T-cell deplete group. After day +30, no significant difference in T-cell reconstitution compared to unmanipulated BM grafts was detected. Reconstitution of CD3+, CD3+CD4+, and CD3+ CD8+ T cells for all groups is illustrated in Figure 2b, c.

Immune reconstitution after transplantation. a Reconstitution of CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+ T cells, CD19+ B cells and CD16/56+ NK cells in the first year after transplantation, points represent mean values/µl. b CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+ T cell counts/µl at days +30, +60, and +90 in comparison to control groups (T-cell depleted and replete unmanipulated BM). p values represent the difference in mean values between the groups. c Reconstitution of CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+ T cell in the first year after transplantation in comparison to control groups (T-cell depleted and replete unmanipulated BM), points represent mean values/µl

Graft vs. host disease

Acute GvHD

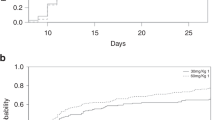

A total of 15 patients (60%) presented without any symptoms of aGvHD. aGvHD grade I was seen in 7 (28%), grade II in two (8%), grade III in one patient (4%). No patient showed grade IV (Table 3, Fig. 3a). In 9 out of 10 patients, aGvHD was limited to the skin and responsive to topical therapy (steroids and tacrolimus) (n = 6) or systemic steroids (n = 3). One patient experienced visceral aGvHD manifestation (liver stage, intestine stage 3) after secondary transplantation, which was responsive to systemic steroids, tacrolimus, ATG, and donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells.

Chronic GvHD

Patients were considered evaluable for chronic GvHD if they engrafted and survived for more than 100 days. Only 3 of the 23 evaluable patients (13%) experienced chronic GvHD, which was limited and transient in all cases (Table 3).

Survival

As of December 2016, 16 of the 25 patients (64%) are alive and disease free, with a median follow-up of 10 years. The 5-year EFS in all patients was 68% (Fig. 3b) and itemized by diagnosis 50% for lymphoid malignancies (ALL/NHL), 67% for myeloid malignancies (AML/MDS(RAEB)/CML/JMML) (Fig. 3c) and 4 out of 4 for MDS RCC patients. The cumulative incidence of relapse among patients with malignant disease (n = 21) was 24% (Fig. 3d). All patients experiencing a relapse died (ALL n = 1, NHL n = 1, AML n = 2, JMML n = 1). The cumulative incidence of TRM was 12% (Fig. 3e). Two ALL patients, tested negative for ADV by PCR prior to transplant, died from ADV sepsis on days +72 and +392 post-transplant. Both patients never showed T-cell reconstitution with 0/µl CD3+ T-cell at day +60 and 39/µl at 1 year, respectively. One ALL patient died from acute right heart failure associated with thrombotic microangiopathy. One patient with trisomy 21 as the underlying condition experienced sudden death most likely unrelated to the allotransplant almost 6 years later. No death was found to be directly associated with GvHD (Table 3). There was no case of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD) observed.

Discussion

In the present study, we report long-term follow-up results from a cohort of 25 pediatric patients, transplanted with T cell-depleted PBSC grafts from MUDs using positive immunomagnetic selection of CD34+ or CD133+ hematopoietic stem cells. To investigate the feasibility and safety of transplanting a defined number of donor T cells along with the stem cell graft, patients received an add-back of 1 × 107/kgBW unselected CD3+ T cells resulting in a median total TCD of 1.97 log together with ATG and CSA/MTX.

One major challenge in alloHSCT is the prevention of GvHD. In previous studies we were able to demonstrate, that depletion of T cells by positive selection of CD34+ PBSCs, along with serotherapy (ATG), can minimize the risk for aGvHD and cGvHD [12, 13]. Importantly, using an add-back of 1 × 107/kgBW unselected CD3+ T cells, along with serotherapy (ATG) and CSA/MTX, did not majorly alter this low incidence compared to our historical group of patients receiving T cell-depleted grafts with 12% vs. 10% of aGvHD grade II–IV and 13% vs. 7.5% of cGvHD, respectively [12].

Compared to reports by Bunin et al. and Geyer et al. [14, 18], who administered add-backs between 1 and 5 × 105/kgBW CD3+ T cells, we infused a 20 to 100-fold higher number of CD3+ T cells. Nevertheless, all three trials report similar rates of aGvHD II–IV (12 vs. 8.3% vs. 15.8%). The incidence of cGvHD, however, was remarkably lower in our cohort with 13% vs. 61.5% vs. 23.3% in evaluable patients [14, 18]. We assume that this difference can be attributed to the combined use of CSA/MTX for post-transplant immunosuppression in our cohort, whereas the other groups employed only CSA or tacrolimus [24]. Serotherapy, using ATG, was applied in all three studies. Compared to trials using unmanipulated BM or T-cell replete PBSC grafts in combination with CSA/MTX or tacrolimus/ATG or alemtuzumab for GvHD prophylaxis, reporting high rates of aGvHD grade II–IV (40 to 55%) and cGvHD (18 to 53%) [5,6,7, 25,26,27], we found a clear reduction in aGvHD grade II–IV as well as cGvHD in our patients. Importantly, there was no death associated with GvHD compared to up to 20% for patients transplanted with unmanipulated PBSC grafts [27]. Taken together, partial ex vivo TCD in combination with serotherapy (ATG) and CSA/MTX results in GvHD rates similar to complete ex vivo TCD without post-transplant immunosuppression and on the other hand to clearly reduced GvHD rates compared to unmanipulated PBSC grafts.

We previously reported a graft failure rate of 16% in patients transplanted with highly enriched CD34+ PBSC grafts [12, 13]. The median CD3+ T-cell dose in these cohorts was 6 × 103/kgBW. Low T-cell numbers (<2 × 105/kgBW CD3+ T cells) in the graft have been reported to be associated with poor engraftment also in adult patients [28]. In the present study, we experienced graft failure in only one patient (4%) who could be successfully re-transplanted from a different MUD. In line with published data [14, 18], these results suggest that defined T-cell add-backs are a reasonable strategy to improve engraftment.

Another major challenge in T cell-depleted HSCT is the delayed T-cell immune reconstitution, which may increase the risk for infection and malignant relapse. Using a T-cell add-back of 1 × 107/kgBW unselected CD3+ T cells we found significantly higher numbers of CD3+, CD3+CD4+, and CD3+CD8+ positive cell at day +60 and CD3+ and CD3+CD8+ at day +90 and +180 post transplantation, to patients in our T cell-depleted control group. Importantly, there was no significant difference in numerical T-cell reconstitution after day +60 in comparison with patients receiving unmanipulated BM, indicating that 1 × 107/kgBW unselected CD3+ T cells are a sufficient number to ensure early and stable T-cell recovery like in BM grafts. Similar T-cell reconstitution data have been reported by Greyer et al. around day +100 [18]. Unfortunately, no earlier time points were assessed in this study. Besides quantity of T cells, the T-cell receptor (TCR)-repertoire after T cell-depleted HSCT is severely skewed and shows significantly reduced diversity during the first year as previously reported [29]. Add-backs of unselected CD3+ T cells should be able to improve TCR repertoire diversity.

We previously reported an increased risk for lethal infectious complications (16% viral, 10% fungal) in the first 6 months post-transplant after T cell-depleted HSCT [12]. In contrast, the current study shows an infection-associated mortality of only 8%. This reduction might be attributed to the improved T-cell recovery in the early post transplantation phase. Both patients dying from ADV infection in the current study never showed any T-cell reconstitution. Our results are in line with infection-associated TRM-rates (9–14.4%) reported from studies using BM or PBSC grafts. [6, 27]. The cumulative incidence of TRM in the present study was 12%. In comparisons to other studies this is a considerable reduction, achieved by the elimination of GvHD-related deaths. TRM of 24% [6, 7, 27, 30] and 31%, of which 11% was due to GvHD [6, 7, 27, 30] was reported for children receiving BM or PBSC graft from MUDs. In adults, transplantation from MUDs resulted in a TRM of 21%, with 12.5% GvHD related, for BM and 23%, with 23% GvHD related, for PBSC grafts [6, 7, 27, 30].

EFS was 64% and the probability of relapse 24% among the 21 patients with malignant disease. These results do not substantially differ from results obtained for pediatric patients in trials using BM or unmanipulated PBSC grafts [6, 7, 26]. However, owing to the low patient number and heterogeneity of underlying diseases, comprehensive conclusions on EFS cannot be drawn. Remarkable, the four MDS patients receiving non-myeloablative conditioning all engrafted with four out of four EFS.

Positive selection of hematopoietic stem cells still represents a reliable and beneficial graft manipulation procedure, receiving renewed attention since a large randomized trial demonstrated significant advantages for AML patients transplanted with CD34-selected PBSC grafts from matched sibling donors [25].

Furthermore, tailored grafts composed of positively selected hematopoietic stem cells with specifically designed T-cell add-backs, e.g., by using negative depletion strategies against TCRαβ+ or CD45RA+, should be considered to enhance safety and improve survival [31,32,33,34].

Bleakley et al. evaluated grafts combining CD34+-selected progenitors with an add-back of up to 1 × 107/kgBW CD45RA+-depleted T cells from MUDs using only tacrolimus, no serotherapy, for GvHD prophylaxis [32]. Rapid T-cell recovery and transfer of protective virus-specific immunity was demonstrated. However, the observed rate of aGvHD grade II–IV was 66%, raising the question, whether combined use of serotherapy, calcineurin inhibitors and MTX might be more efficient in this context.

In conclusion, our approach demonstrates that in pediatric allotransplant recipients, who often receive grafts from adult donors with extraordinarily high T-cell numbers, a partial TCD, down to a defined dosage of 1 × 107 CD3+/kgBW, in combination with CSA/MTX post-transplant GvHD prophylaxis, is feasible and safe in terms of ensured engraftment, low rates of GvHD, fast immune recovery, and a relapse rate within the expected range. Larger trials are warranted to confirm these data.

References

Majhail NS, Farnia SH, Carpenter PA, Champlin RE, Crawford S, Marks DI, et al. Indications for autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: guidelines from the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1863–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.07.032

Welniak LA, Blazar BR, Murphy WJ. Immunobiology of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:139–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141606

Seggewiss R, Einsele H. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic transplantation and expanding options for immunomodulation: an update. Blood. 2010;115:3861–8. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-12-234096

Bleakley M, Riddell SR. Molecules and mechanisms of the graft-versus-leukaemia effect. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:371–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1365

Sedlacek P, Formankova R, Keslova P, Sramkova L, Hubacek P, Krol L, et al. Low mortality of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from 7 to 8/10 human leukocyte antigen allele-matched unrelated donors with the use of antithymocyte globulin. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:745–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1705524

Kalwak K, Porwolik J, Mielcarek M, Gorczynska E, Owoc-Lempach J, Ussowicz M, et al. Higher CD34(+) and CD3(+) cell doses in the graft promote long-term survival, and have no impact on the incidence of severe acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease after in vivo T cell-depleted unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1388–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.04.001

Shaw PJ, Kan F, Woo Ahn K, Spellman SR, Aljurf M, Ayas M, et al. Outcomes of pediatric bone marrow transplantation for leukemia and myelodysplasia using matched sibling, mismatched related, or matched unrelated donors. Blood. 2010;116:4007–15. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-01-261958

Wagner JE, Santos GW, Noga SJ, Rowley SD, Davis J, Vogelsang GB, et al. Bone marrow graft engineering by counterflow centrifugal elutriation: results of a phase I-II clinical trial. Blood. 1990;75:1370–7.

Socie G, Stone JV, Wingard JR, Weisdorf D, Henslee-Downey PJ, Bredeson C, et al. Long-term survival and late deaths after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Late Effects Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:14–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199907013410103

Lee SJ, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:215–33. https://doi.org/10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026

Remberger M, Beelen DW, Fauser A, Basara N, Basu O, Ringden O. Increased risk of extensive chronic graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation using unrelated donors. Blood. 2005;105:548–51. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-03-1000

Lang P, Handgretinger R, Niethammer D, Schlegel PG, Schumm M, Greil J, et al. Transplantation of highly purified CD34+ progenitor cells from unrelated donors in pediatric leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:1630–6. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-04-1203

Lang P, Klingebiel T, Bader P, Greil J, Schumm M, Schlegel PG, et al. Transplantation of highly purified peripheral-blood CD34+ progenitor cells from related and unrelated donors in children with nonmalignant diseases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:25–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704303

Bunin N, Aplenc R, Grupp S, Pierson G, Monos D. Unrelated donor or partially matched related donor peripheral stem cell transplant with CD34+ selection and CD3+ addback for pediatric patients with leukemias. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:143–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1705211

Marks DI, Khattry N, Cummins M, Goulden N, Green A, Harvey J, et al. Haploidentical stem cell transplantation for children with acute leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:196–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06140.x

Ball LM, Lankester AC, Bredius RG, Fibbe WE, van Tol MJ, Egeler RM. Graft dysfunction and delayed immune reconstitution following haploidentical peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35(Suppl 1):S35–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704842

Landgren O, Gilbert ES, Rizzo JD, Socie G, Banks PM, Sobocinski KA, et al. Risk factors for lymphoproliferative disorders after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113:4992–5001. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-09-178046

Geyer MB, Ricci AM, Jacobson JS, Majzner R, Duffy D, Van de Ven C, et al. T cell depletion utilizing CD34(+) stem cell selection and CD3(+) addback from unrelated adult donors in paediatric allogeneic stem cell transplantation recipients. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:205–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09048.x

Lang P, Bader P, Schumm M, Feuchtinger T, Einsele H, Fuhrer M, et al. Transplantation of a combination of CD133+ and CD34+ selected progenitor cells from alternative donors. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:72–79.

Schumm M, Lang P, Taylor G, Kuci S, Klingebiel T, Buhring HJ, et al. Isolation of highly purified autologous and allogeneic peripheral CD34+ cells using the CliniMACS device. J Hematother. 1999;8:209–18. https://doi.org/10.1089/106161299320488

Sutherland HJ, Hogge DE, Eaves CJ. Characterization, quantitation and mobilization of early hematopoietic progenitors: implications for transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;18(Suppl 1):S1–4.

Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18:695–706.

Kohl M, Plischke M, Leffondre K, Heinze G. PSHREG: a SAS macro for proportional and nonproportional subdistribution hazards regression. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 2015;118:218–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2014.11.009

Chen GL, Zhang Y, Hahn T, Abrams S, Ross M, Liu H, et al. Acute GVHD prophylaxis with standard-dose, micro-dose or no MTX after fludarabine/melphalan conditioning. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:248–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2013.167

Pasquini MC, Devine S, Mendizabal A, Baden LR, Wingard JR, Lazarus HM, et al. Comparative outcomes of donor graft CD34+ selection and immune suppressive therapy as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in complete remission undergoing HLA-matched sibling allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3194–201. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7071

Meisel R,Klingebiel T,Dilloo D,German/Austrian Pediatric Registry for Stem Cell Transplantation Peripheral blood stem cells versus bone marrow in pediatric unrelated donor stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2013;121:863–5. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-12-469668.

Anasetti C, Logan BR, Lee SJ, Waller EK, Weisdorf DJ, Wingard JR, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1487–96. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1203517

Urbano-Ispizua A, Rozman C, Pimentel P, Solano C, de la Rubia J, Brunet S, et al. The number of donor CD3(+) cells is the most important factor for graft failure after allogeneic transplantation of CD34(+) selected cells from peripheral blood from HLA-identical siblings. Blood. 2001;97:383–7.

Eyrich M, Leiler C, Lang P, Schilbach K, Schumm M, Bader P, et al. A prospective comparison of immune reconstitution in pediatric recipients of positively selected CD34+ peripheral blood stem cells from unrelated donors vs recipients of unmanipulated bone marrow from related donors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:379–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704158

Peters C, Schrappe M, von Stackelberg A, Schrauder A, Bader P, Ebell W, et al. Stem-cell transplantation in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a prospective international multicenter trial comparing sibling donors with matched unrelated donors-The ALL-SCT-BFM-2003 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1265–74. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.9747

Lang P, Feuchtinger T, Teltschik HM, Schwinger W, Schlegel P, Pfeiffer M, et al. Improved immune recovery after transplantation of TCRalphabeta/CD19-depleted allografts from haploidentical donors in pediatric patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(Suppl 2):S6–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2015.87

Bleakley M, Heimfeld S, Loeb KR, Jones LA, Chaney C, Seropian S, et al. Outcomes of acute leukemia patients transplanted with naive T cell-depleted stem cell grafts. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2677–89. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI81229

Locatelli F, Merli P, Pagliara D, Li Pira G, Falco M, Pende D, et al. Outcome of children with acute leukemia given HLA-haploidentical HSCT after alphabeta T-cell and B-cell depletion. Blood. 2017;130:677–85. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-04-779769

Maschan M, Shelikhova L, Ilushina M, Kurnikova E, Boyakova E, Balashov D, et al. TCR-alpha/beta and CD19 depletion and treosulfan-based conditioning regimen in unrelated and haploidentical transplantation in children with acute myeloid leukemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2015.343

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 685, TP C3), from the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), partner site Tuebingen and from the Reinhold-Beitlich Stiftung to P.L. and R.H. We thank Barbara Lang, M.D. for reviewing the manuscript and the Stiftung fuer krebskranke Kinder Tuebingen e.V. for continuous support.

Author contributions

C.M.S., M.E., P.S., and P.L. collected and analyzed data, performed statistical analysis and wrote the paper. M.E., R.H., and P.L., designed the study. M.E., J.G., P.B., T.F., M.P. provided patients, M.S. provided data, C.P.S. critically reviewed the manuscript. All contributors had access to primary trial data, approved the manuscript, and agree with the presented data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seitz, C.M., Eyrich, M., Greil, J. et al. Favorable immune recovery and low rate of GvHD in children transplanted with partially T cell-depleted PBSC grafts. Bone Marrow Transplant 54, 53–62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-018-0212-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-018-0212-7