Abstract

Background

Adverse events during postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy may reflect prognosis in resectable advanced colorectal cancer. This study assessed the association between these events and survival in advanced colorectal cancer patients.

Methods

We analysed patient data from four Japanese randomised controlled trials on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II or III colorectal cancer. Adverse events were defined as the maximum grade within 6 months. The primary outcome was overall survival, analysed using a multivariate-adjusted Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

A total of 4,046 patients with advanced colorectal cancer undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy were included. Maximum adverse event grades were: 739 (18%) grade 0, 960 (24%) grade 1, 1511 (37%) grade 2, 779 (19%) grade 3 and 57 (1.4%) grade 4. Compared to grade 0, hazard ratios for overall survival were 0.77 (95% CI, 0.61–0.98) for grade 1, 0.70 (95% CI, 0.56–0.87) for grade 2, 0.69 (95% CI, 0.53–0.91) for grade 3 and 1.12 (95% CI, 0.62–2.04) for grade 4.

Conclusions

The severity of adverse events during adjuvant chemotherapy correlated with survival outcomes in advanced colorectal cancer. Mild to moderate events were linked to improved prognosis, while absence suggested poorer outcomes, indicating a need for alternative treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common and deadly malignancies worldwide [1]. Surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy is a standard treatment for locally advanced CRC [2, 3]. Despite advancements in adjuvant chemotherapy regimens [4], approximately 20–30% of patients with advanced CRC develop recurrence, which is often incurable [5, 6]. Accurate assessment of recurrence risk during treatment is essential to guide treatment decisions and optimise therapeutic strategies.

Emerging evidence suggests that chemotherapy-related adverse events may serve as prognostic markers for CRC treatment efficacy. While adverse events often lead to dose reductions and treatment interruptions, which may negatively impact prognosis, some studies have reported a paradoxical association between adverse events and improved outcomes in metastatic CRC. A meta-analysis showed that the occurrence of skin rash during systemic chemotherapy with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor drugs represents a better prognosis in metastatic CRC [7]. Similarly, clinical studies have reported that hand-foot syndrome during capecitabine-based chemotherapy was associated with improved prognosis in metastatic CRC treated with capecitabine-based systemic chemotherapy [8,9,10]. Despite these findings, the association between adverse events and prognosis in patients with advanced CRC who receive adjuvant chemotherapy remains unclear. Therefore, we hypothesised that the severity of adverse events during adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced CRC is associated with prognosis.

To test this hypothesis, we leveraged resources from four randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to assess the prognostic impact of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with advanced CRC. Our findings may help refine adjuvant chemotherapy selection by incorporating adverse event severity into treatment decision-making.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a pooled analysis of individual patient data from four RCTs [11,12,13,14] conducted by the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer (JFMC). These studies evaluated the prognostic effect of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with resected pathological stage II or III CRC, classified according to the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) version 6.

This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic impact of adverse events occurring within 6 months after the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy. The following adjuvant chemotherapy regimens were used in each clinical trial: uracil-tegafur plus leucovorin (UFT/LV) for six or 18 months in JFMC 33 [11], uracil and tegafur (UFT) or tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil/potassium (S-1) for 12 months in JFMC 35 [12], capecitabine for 6 or 12 months in JFMC 37 [13], and modified FOLFOX6 (mFOLFOX6) for 6 months in JFMC 41 [14]. Eligible patients underwent curative resection with D2–3 lymph node dissection (intermediate or extended main lymph node dissection) [15] for accurate staging and therapy. We excluded patients with either (1) stage I or IV, (2) D1 lymph node dissection (complete pericolic/perirectal lymph node dissection) [15] or insufficient data on lymph node dissection, or (3) missing data on adverse events.

Definition of adverse event

Each study prespecified that physicians must report the maximum grade of any adverse events every 6 months after the start of adjuvant chemotherapy, according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 3.0 or 4.0. All information on adverse events was extracted from the case report forms for each trial.

The present study categorised adverse events into the following seven major categories: haematological, gastrointestinal, metabolism and nutrition, skin and subcutaneous tissue, hepatic, renal and other disorders. The haematological adverse events included leukopenia, neutropenia, lymphopenia, febrile neutropenia, anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Gastrointestinal disorders comprised diarrhoea, mucositis, stomatitis, nausea and vomiting. Metabolism and nutrition disorders were indicated by appetite loss and fatigue. Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders involved rash, desquamation, hyperpigmentation, hand-foot syndrome and alopecia. Hepatic disorders were characterised by elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, hypoproteinaemia and hypoalbuminaemia. Renal disorders included increased creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels. Other adverse events included dysgeusia, peripheral sensory neuropathy, arrhythmias, allergic reactions and pneumonitis.

We defined total adverse events as the maximum grade of the seven categorised adverse events. We used the maximum grade of total adverse events within 6 months after the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy as the primary analysis.

Outcome

The primary outcome was overall survival (OS), calculated as the number of days from the registration date of the clinical trials until death, loss to follow-up, or survival within the cutoff period of 5 years. Patients who had not experienced any event of interest were censored at the last follow-up date or at the end of the 5-year observational period. The secondary outcome was relapse-free survival (RFS), which was defined as the period between the registration date and recurrence or death.

Covariates

We classified the following data on patient covariates: age (<70 vs. ≥70 years), sex (male vs. female), body mass index (BMI) (18.5–25 vs. <18.5 vs. >25 kg/m2), performance status (PS; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG]; 0 vs. 1 or 2), tumour location (colon vs. rectum [segment from the height of the sacral promontory to the anal verge] (15)), tumour differentiation (well to moderate vs. other), UICC pathological T-stage (T1–T3 vs. T4) and pathological N-stage (N0 vs. N1 vs. N2).

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics were reported as descriptive statistics, with continuous variables expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. Binary and categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Cumulative survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. To evaluate the association of the maximum grade of total adverse events with OS and RFS, we used Cox proportional hazards models including the above covariates. The remaining individuals, with missing or unclassified data, were assigned to the majority category.

As a sensitivity analysis, we excluded patients who discontinued treatment or died within 6 months to reduce bias from non-treatment-related mortality and ensure that only those receiving adequate chemotherapy exposure were analysed. Additionally, we analysed the association between the maximum grade of each of the seven adverse events and OS.

For subgroup analyses, we examined the association between the maximum grade of total adverse events and OS, stratified by chemotherapy regimen (single-agent [UFT/LV, S-1 or capecitabine] vs. double-agent [mFOLFOX6]) and treatment duration (6 months vs. more than 6 months).

All significance tests were two-sided, and p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

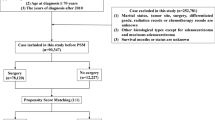

Among the four JFMC clinical trials, we documented data on 4046 patients with curatively resected stage II or III CRC, excluding five patients with stage I or IV, 15 patients who had undergone D1 lymphadenectomy, and eight patients with missing adverse event grade data (Fig. 1).

aThe stage was determined based on clinicopathological diagnosis and the UICC TNM classification, version 6. bD1, complete pericolic or perirectal lymph node dissection. AE adverse event, JFMC Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer, S-1 tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil/potassium, UFT/LV uracil and tegafur, UFT/LV uracil-tegafur plus leucovorin.

Adverse events during adjuvant chemotherapy

Among those included in the study, the number of patients who experienced the maximum adverse events within 6 months after the start of adjuvant chemotherapy was 739 (18%) with Grade 0, 960 (24%) with Grade 1, 1511 (37%) with Grade 2, 779 (19%) with Grade 3 and 57 (1.4%) with Grade 4. The number of patients who experienced maximum adverse events during the entire follow-up period was 608 (15%) in Grade 0, 932 (23%) with Grade 1, 1643 (40%) with Grade 2, 853 (21%) with Grade 3 and 63 (1.5%) with Grade 4 (Table 1).

Patients’ characteristics according to the maximum grade of adverse events within the first 6 months

Table 2 shows the patients’ characteristics according to the maximum grade of total adverse events within the first 6 months. The Grade 0 group exhibited a trend toward younger age (median age: 62 years in Grade 0, 64 years in Grade 1, 64 years in Grade 2, 64 years in Grade 3 and 68 years in Grade 4) and had a higher proportion of males (67% in Grade 0, 61% in Grade 1, 51% in Grade 2, 50% in Grade 3 and 51% in Grade 4). Additionally, the BMI was higher in the Grade 0 group (median BMI: 22.0 kg/m2 in Grade 0, 21.8 kg/m2 in Grade 1, 21.7 kg/m2 in Grade 2, 21.5 kg/m2 in Grade 3 and 20.9 kg/m2 in Grade 4), and the proportion of rectal cancer cases was also elevated (54% in Grade 0, 42% in Grade 1, 37% in Grade 2, 27% in Grade 3 and 33% in Grade 4). Furthermore, the Grade 0 group demonstrated a higher proportion of pN0 cases (22% in Grade 0, 15% in Grade 1, 13% in Grade 2, 13% in Grade 3 and 11% in Grade 4). Regarding the scheduled administration period of adjuvant chemotherapy, the proportion of patients who received treatment for more than 6 months was higher in the Grade 0 group (70% in Grade 0, 57% in Grade 1, 49% in Grade 2, 35% in Grade 3 and 19% in Grade 4).

Treatment discontinuation, dose reduction, and dose suspension rates stratified by maximum adverse event grade are summarised in Table 2. As expected, higher-grade adverse events were associated with increased rates of treatment modifications.

Overall survival (OS) and relapse free survival (RFS)

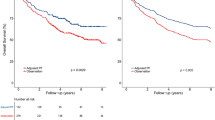

The Grade 0 group was associated with poorer OS than the Grade 1–3 groups. Conversely, the Grade 4 group exhibited poor OS, similar to the poor prognosis observed in the Grade 0 group. Kaplan-Meier curves for OS, presented in Fig. 2, demonstrate a significant difference among the groups (P = 0.011). Compared to Grade 0, the multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of the maximum grade of total adverse events within the first 6 months for OS was 0.77 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61–0.98, P = 0.035) in Grade 1; 0.70 (95% CI, 0.56–0.87, P = 0.0017) in Grade 2; 0.69 (95% CI, 0.53–0.91, P = 0.0074) in Grade 3; and 1.12 (95% CI, 0.62–2.04, P = 0.71) in Grade 4 (Table 3).

We also examined the association between adverse event severity and OS within each chemotherapy regimen (Supplementary Table 1). The trend of improved prognosis among patients with Grade 1–3 adverse events, compared with those with Grade 0, was generally consistent across different regimens. However, in the UFT/LV for 6 months subgroup, patients with Grade 2 or Grade 3 adverse events, and in the mFOLFOX6 for 6 months subgroup, those with Grade 1, exhibited a trend toward poorer OS than Grade 0, although these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Similarly, the Grade 0 group had a poorer RFS than the Grade 1–3 groups. The Grade 4 group also showed poor RFS, comparable to the unfavourable prognosis of the Grade 0 group. Kaplan-Meier curves for RFS, presented in Fig. 3, also showed a significant difference among the groups (P < 0.0001). Compared to Grade 0, the multivariable-adjusted HR of the maximum grade of total adverse events within the first 6 months for RFS was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.62–0.87; P = 0.0004) in Grade 1, 0.73 (95% CI, 0.62–0.86; P = 0.0001) in Grade 2, 0.67 (95% CI, 0.56–0.82; P < 0.0001) in Grade 3 and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.66–1.64; P = 0.87) in Grade 4 (Table 4).

Sensitivity analysis

To evaluate whether early treatment discontinuation affected survival outcomes, we reanalysed the data excluding patients who either died or discontinued treatment within the first 6 months (Supplementary Table 2). Similar to the main analysis, the Grade 0 group exhibited poorer OS than the Grade 1–3 groups (HR: 0.68 [95%CI, 0.51–0.91, P = 0.010] in Grade 1; HR: 0.72 [95%CI, 0.55–0.95, P = 0.019] in Grade 2; and HR: 0.66 [95%CI, 0.45–0.96, P = 0.031] in Grade 3). Conversely, the Grade 4 group had poor OS, comparable to the poor prognosis observed in the Grade 0 group (HR: 1.31 [95%CI, 0.47–3.60, P = 0.61]).

Furthermore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to assess the association between the maximum grade of each of the seven adverse events and OS (Supplementary Table 3). Similar to the findings for total adverse events, Grade 1–3 haematological adverse events were significantly associated with improved OS (HR: 0.80 [95% CI, 0.66–0.98; P = 0.034] for Grade 1; HR: 0.67 [95% CI, 0.52–0.87; P = 0.0021] for Grade 2; HR: 0.64 [95% CI, 0.42–1.00; P = 0.048] for Grade 3). Additionally, Grade 1 skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders were significantly associated with improved OS (HR: 0.64 [95% CI, 0.51–0.82; P = 0.0003]), whereas higher grades did not exhibit a consistent trend.

Subgroup analysis

Regarding chemotherapy regimens, the Grade 0 group was associated with poorer OS than the Grade 1–3 groups treated with single-agent therapy (Supplementary Table 4). In contrast, among those receiving double-agent therapy, Grade 1 showed a trend toward poorer OS compared to Grade 0 (HR: 1.31 [95% CI: 0.38–4.56]), though this difference was not statistically significant. Regarding the scheduled administration period, the Grade 0 group was consistently associated with a poorer prognosis than the Grade 1–3 groups, regardless of treatment duration (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

This study demonstrated that the severity of adverse events during adjuvant chemotherapy is associated with survival outcomes in patients with stage II or III CRC. Mild to moderate adverse events (Grade 1–3) were associated with improved OS and RFS, suggesting their potential role as surrogate markers of effective chemotherapy. In contrast, the absence of adverse events (Grade 0) was consistently linked to a poorer prognosis, highlighting the need for alternative treatment strategies for these patients. These findings suggest that monitoring and managing adverse events can provide valuable insights into the treatment efficacy and guide individualised therapeutic strategies in the adjuvant setting for CRC.

This study is the first to demonstrate the association between the severity of various adverse events and prognosis in patients with stage II and III CRC undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy. A post hoc analysis in a clinical trial to evaluate the prognostic effect of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with advanced CRC indicated that patients with hand-foot syndrome had a better prognosis than those without adverse events [16]. Our study expanded on this finding by investigating not only hand-foot syndrome but also the severity of any other adverse events and their association with prognosis. A previous study on systemic chemotherapy for metastatic CRC reported that fewer adverse events were associated with poorer prognosis [17]. This finding may partially support the results of our study, highlighting the complex interplay between treatment-related toxicity and patient outcomes.

The underlying mechanism linking the absence of adverse events (Grade 0) to poor prognosis may be rooted in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of chemotherapy. Adverse events are often considered surrogate markers for adequate drug exposure and therapeutic efficacy. For example, studies have shown that the occurrence of specific toxicities, such as peripheral neuropathy or hand-foot syndrome, is associated with improved survival in patients receiving oxaliplatin or capecitabine, respectively, suggesting that such toxicities may indicate sufficient drug delivery and activity [10, 18]. In contrast, patients who do not experience adverse events may metabolise chemotherapeutic agents too rapidly or inefficiently, leading to sub-therapeutic drug levels. Rapid metabolism can prevent drugs from achieving the necessary blood concentrations to exert cytotoxic effects on tumour cells [19]. This phenomenon could explain why these patients lacked both adverse events and sufficient therapeutic benefits, ultimately resulting in poorer outcomes.

This study has several strengths. First, this is the first study to investigate the association between various adverse events, including haematological toxicity, hand-foot syndrome and prognosis. Second, this study represents the largest analysis to date, including 4,046 patients with locally advanced CRC treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Third, the data were accurately collected with minimal missing values, as this study was a pooled analysis of RCTs. The large sample size and comprehensive data collection enhanced the reliability of the findings and provided valuable insights into the prognostic significance of adverse events in this context.

This study has some limitations. First, unmeasured confounding factors related to adverse events and prognoses may exist. For instance, the current study lacked biomarker information, such as MSI, RAS, and BRAF, which are important prognostic factors for predicting the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy [20, 21]. Future studies, including subgroup analyses of each of these biomarkers, are needed. Second, the pooled analysis included patients treated with various regimens, some of which are not currently recommended as standard adjuvant chemotherapy (e.g. three or 6 months) [5], such as UFT/LV for 18 months in JFMC 33 [11], UFT/LV or S-1 for 12 months in JFMC 35 [12] and capecitabine for 12 months in JFMC 37 [13, 22]. However, sensitivity analysis showed similar results for subgroups with durations of 6 months and more than 6 months, suggesting that the impact of this limitation is minimal (Supplementary Table 4). When further stratified by individual regimens, we observed that in certain regimens, patients with mild to moderate adverse events showed a trend toward poorer prognosis compared with those with no adverse events (Supplementary Table 1). This discrepancy is likely attributable to the small sample sizes in these subgroups, indicating the need for further accumulation of cases to validate these findings. Future large-scale clinical trials focusing on currently recommended adjuvant chemotherapy regimens are warranted to confirm these results. Third, the study population consisted solely of Japanese patients, with 95% having a good performance status (PS 0), raising questions regarding the generalisability of the findings to other racial or ethnic groups. Differences in adverse event profiles and prognoses among populations necessitate further validation in diverse cohorts.

In conclusion, the prognosis of patients with advanced CRC is associated with the severity of adverse events during adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients who did not experience adverse events had poorer survival outcomes, suggesting that they may have received suboptimal chemotherapy exposure. These findings highlight the potential role of adverse events as surrogate markers of chemotherapy efficacy. Further research is needed to determine whether modifying chemotherapy intensity or introducing alternative regimens could improve outcomes in patients who experience few or no adverse events.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49.

Argilés G, Tabernero J, Labianca R, Hochhauser D, Salazar R, Iveson T, et al. Localised colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1291–305.

Yoshino T, Argilés G, Oki E, Martinelli E, Taniguchi H, Arnold D, et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis treatment and follow-up of patients with localised colon cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1496–510.

Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:1–42.

Grothey A, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, Yoshino T, Paul J, Taieb J, et al. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1177–88.

Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:233–54.

Petrelli F, Borgonovo K, Barni S. The predictive role of skin rash with cetuximab and panitumumab in colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published trials. Target Oncol. 2013;8:173–81.

Stintzing S, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Vehling-Kaiser U, Stauch M, Hass HG, Dietzfelbinger H, et al. Correlation of capecitabine-induced skin toxicity with treatment efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the German AIO KRK-0104 trial. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:206–11.

Hofheinz RD, Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Laubender RP, Gencer D, Burkholder I, et al. Capecitabine-associated hand-foot-skin reaction is an independent clinical predictor of improved survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1678–83.

Watts K, Wills C, Madi A, Palles C, Maughan TS, Kaplan R, et al. Genetic variation in ST6GAL1 is a determinant of capecitabine and oxaliplatin induced hand-foot syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2022;151:957–66.

Sadahiro S, Tsuchiya T, Sasaki K, Kondo K, Katsumata K, Nishimura G, et al. Randomized phase III trial of treatment duration for oral uracil and tegafur plus leucovorin as adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage IIB/III colon cancer: final results of JFMC33-0502. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2274–80.

Oki E, Murata A, Yoshida K, Maeda K, Ikejiri K, Munemoto Y, et al. A randomized phase III trial comparing S-1 versus UFT as adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II/III rectal cancer (JFMC35-C1: ACTS-RC). Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1266–72.

Tomita N, Kunieda K, Maeda A, Hamada C, Yamanaka T, Sato T, et al. Phase III randomised trial comparing 6 vs. 12-month of capecitabine as adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III colon cancer: final results of the JFMC37-0801 study. Br J Cancer. 2019;120:689–96.

Yoshino T, Kotaka M, Shinozaki K, Touyama T, Manaka D, Matsui T, et al. JOIN trial: treatment outcome and recovery status of peripheral sensory neuropathy during a 3-year follow-up in patients receiving modified FOLFOX6 as adjuvant treatment for stage II/III colon cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharm. 2019;84:1269–77.

Japanese Society for Cancer of the C, Rectum. Japanese Classification of colorectal, appendiceal, and anal carcinoma: the 3d English edition [secondary publication]. J Anus Rectum Colon. 2019;3:175–95.

Twelves C, Scheithauer W, McKendrick J, Seitz JF, Van Hazel G, Wong A, et al. Capecitabine versus 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: final results from the X-ACT trial with analysis by age and preliminary evidence of a pharmacodynamic marker of efficacy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1190–7.

Schuell B, Gruenberger T, Kornek GV, Dworan N, Depisch D, Lang F, et al. Side effects during chemotherapy predict tumour response in advanced colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:744–8.

Hines RB, Schoborg C, Sumner T, Thiesfeldt DL, Zhang S. The associations of oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy, sociodemographic characteristics, and clinical characteristics with time to fall in older adults with colorectal cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2024;193:1271–80.

Hahn M, Roll SC. The influence of pharmacogenetics on the clinical relevance of pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions: drug–gene, drug–gene–gene and drug–drug–gene interactions. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:487.

Böckelman C, Engelmann BE, Kaprio T, Hansen TF, Glimelius B. Risk of recurrence in patients with colon cancer stage II and III: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:5–16.

Cohen R, Liu H, Fiskum J, Adams R, Chibaudel B, Maughan TS, et al. BRAF V600E mutation in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer: an analysis of individual patient data from the ARCAD database. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1386–95.

Suto T, Ishiguro M, Hamada C, Kunieda K, Masuko H, Kondo K, et al. Preplanned safety analysis of the JFMC37-0801 trial: a randomized phase III study of six months versus twelve months of capecitabine as adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2017;22:494–504.

Acknowledgements

This study was designed and organised by the JFMC Database Service Committee. This study was also supported in part by the nonprofit organisation Epidemiological & Clinical Research Information Network (ECRIN).

Funding

This study was supported by the Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer (JFMC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HK, MH and YN conceived the study. HK, MH, YN, KO, MM and KT designed the analyses and performed a literature search. HK, MH, YN, KO, MM and KT collected the clinical data. HK, MH, YN, KO, MM and KT analysed and interpreted the data. HK and MH drafted the manuscript. TA, MK, HM, SM, KK, JS, HY and TY critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. HK, MH, YN, KO, MM, KT, TA, MK, HM, SM, KK, JS, HY and TY contributed to the interpretation of results, approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This pooled analysis was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Epidemiological and Clinical Research Information Network (JFMC-DB2020-06).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawamura, H., Honda, M., Nakayama, Y. et al. Adverse events of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy predict survival outcomes in locally advanced colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of Japanese clinical trials. Br J Cancer 133, 1660–1667 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03199-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03199-8