Abstract

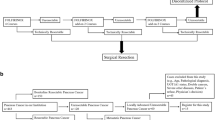

The biggest impact on increasing survival for pancreatic cancer has come about by combining surgical resection with systemic chemotherapy. This groundbreaking paradigm has come under increasing scrutiny relating to the choice of adding chemoradiotherapy to chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone, neoadjuvant versus adjuvant therapy and the optimal regimens. The paradigm has also been challenged in that a distinction needs to be made between ‘resected’ with ‘resectable’ pancreatic cancer, since if only the former is considered, this leads to a biased prognostically favourable patient group being analysed. Moreover, the distinction between resectable, borderline resectable and unresectable cancers is claimed to be so unreliable that this classification should be discouraged in favour of upfront chemotherapy for all patients and not necessarily using either FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine-capecitabine. The results of a series of recent trials including the RTOG0848 trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with or without chemoradiation and the NORPACT-1 trial of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX versus upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer have significantly contributed to the clarification of some these questions. The results of long-term follow-up studies of the adjuvant PRODIGE24 trial comparing FOLFIRINOX with gemcitabine and the ESPAC4 trial of gemcitabine-capecitabine versus gemcitabine have also consolidated and expanded the applicability of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adjuvant chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic cancer challenged as the established reference standard

The pivotal European Study Group (ESPAC) ESPAC1 and ESPAC1-Plus trials published in the Lancet and New England Journal of Medicine in 2001-2004, showed that post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy but not radiochemotherapy substantially improved overall and 5 year survival rates compared to surgical removal alone in patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [1, 2]. These trials were based on using only 5-fluorouracil (5FU) monotherapy (with the 5FU enhancer leucovorin) as the adjuvant therapy, and received considerable scepticism and criticism especially from radiation oncologists in the USA [3, 4]. Further studies from the ESPAC, Charité Onkologie (CONKO) and Japan Adjuvant Study Group of Pancreatic Cancer (JASPAC) teams have confirmed the survival advantage of adjuvant monochemotherapy not only with 5FU but also with gemcitabine, and the oral agent S1 (comprising the 5FU prodrug tegafur, plus the enhancers gimeracil and oteracil potassium) [5,6,7,8].

These trials evolved into adjuvant combination chemotherapy regimens providing even greater overall and 3–5 year survival rates [9, 10]. The ESPAC4 study showed improved overall survival with the combination of gemcitabine with the oral 5-FU prodrug capecitabine (GemCap) finding an increased 5-year overall survival of 28.8% compared to 16.3% for gemcitabine monotherapy [9]. The ESPAC4 study had relatively unrestricted eligibility criteria with no upper age limit and no constraints on serum CA19-9 levels [9]. The France-Canada PRODIGE24-CCTG PA.6 trial demonstrated even more striking results using modified (m)FOLFIRINOX (comprising 5-FU, FA, irinotecan and oxaliplatin) with a 3-year overall survival of 63.4% compared to 48.6% using gemcitabine [10]. mFOLFIRINOX however was associated with greater toxicity than gemcitabine and the PRODIGE24 trial was more stringent in its selection criteria, requiring patients aged 79 years or less, with a WHO performance status of 0 or 1, no significant cardiovascular disease and a postoperative serum tumour marker CA19-9 level <180 KU/L [10]. In real world practice, this additional toxicity burden translates into less than 50% of patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy having mFOLFIRINOX, falling to less than 10% of those aged >70 years [11, 12].

Interestingly, the APACT study comparing gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel against gemcitabine did not meet its primary end point of independently assessed median disease free survival (19.4 versus 18.8 months respectively, hazard ratio [HR] of 0.88 with 95% confidence [CI], 0.729–1.063; P = 0.18), although the median investigator-assessed disease free survival was significant (16.6 versus 13.7 months respectively, HR of 0.82 [95% CI, 0.694–0.965]; P = 0.02), and also overall survival was not significantly different initially but was on further follow up [13]. This apparent discrepancy highlights the challenges of surrogate endpoints such as disease free survival and local investigator versus independent review for adjuvant studies in PDAC. At the 5-year follow-up point the median overall survival was 41.8 months for gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel versus 37.7 months for gemcitabine monotherapy, with 5 year overall survival rates of 38% and 31% respectively with an HR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.678–0.947; P = 0.0091) [13]. Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel is not approved by the FDA as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. The current European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) pancreatic cancer guidelines also state that there is no role for gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel in the adjuvant setting, whilst mFOLFIRINOX is the established reference standard for fit patients, with GemCap as an option, although typically this combination is now reserved for patients not eligible for, or choosing not to have, mFOLFIRINOX [14].

A post hoc analysis of the ESPAC3 trial identified completion of all six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy as a key favourable prognostic factor for overall survival rather than starting the chemotherapy earlier after resection, which was later confirmed by the PRODIGE24/CCTG PA.6 trial [15, 16].

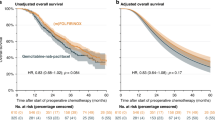

The CONKO-001 trial when first reported only found a significant difference for disease free survival with gemcitabine compared to observation but with prolonged follow up there was significant overall survival difference (Table 1) [5, 17]. Extended median follow up of 69.7 months in the PRODIGE24/CCTG PA.6 trial showed sustained improvement in median survival differences and a 5 year overall survival rate 43.2% for mFOLFIRINOX versus 31.4% for gemcitabine [16]. With further follow up now of 104 months in the ESPAC4 trial there was a sustained median overall survival of 31.6 months in the GemCap group compared to 28.4 months with gemcitabine alone, translating into 5 year survival estimates of 32% (95% CI, 27–36) and 25% (95% CI, 21–30), respectively [18].

Despite the ESMO recommendations being consistent with other international guidelines notably the USA National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology and the England National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) in recommending adjuvant chemotherapy as standard practice for resectable PDAC, there are a number of challenges to this position [19, 20]. Firstly, it is argued that that a distinction needs to be made in clinical trials comparing ‘resected’ with ‘resectable’ pancreatic cancer, since if we only consider the former then the inclusion criteria are biased leading to a prognostically false favourable patient group being analysed [21, 22]. Secondly the distinction between ‘resectable’ and ‘borderline resectable’ groups is so unreliable these should be considered as single entity that we refer to as ‘resectable(*)’ [23,24,25]. Reni and Orsi stated ‘that surgical classification (i.e. distinguishing between resectable, borderline resectable and unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinomas), apart from lacking prognostic validation, is irreproducible and its use should be discouraged’ [26]. Thus we can only consider two categories of clinically relevant patient groups namely non-metastatic (1) locally ‘resectable (*)’ and (2) ‘unresectable’. In which case and thirdly all ‘resectable(*)’ and ‘non-resectable’ patients should be treated in the same way with upfront systemic therapies, using neoadjuvant and induction combination chemotherapy regimens [27]. Finally according to Reni and colleagues since mFOLFIRINOX and GemCap have never been tested in the ‘resectable (*)’ setting then neither can be considered the reference standard, and they recommend consideration of alternative regimens such as PAXG (cisplatin, nab-paclitaxel, capecitabine and gemcitabine) which in the case of PAXG has been tested in ‘resectable(*)’ patients [28]. Further analysis of these arguments using published data also needs to be based on a thorough understanding of modern surgical developments as the cornerstone of multi-modality treatments.

Advances in surgery underpinning multi-modality treatment

Whilst surgery remains the only curative modality for a small proportion of patients with non-metastatic PDAC, its role and scope have significantly evolved in the era of multimodal therapy with very low post-operative mortality rates and improving long-term survival and good quality of life measures [29, 30]. Anatomical/empirical criteria for resectability, internationally accepted and applied in the form of the Alliance and NCCN staging systems widely guide surgical decisions (Table 1; Fig. 1a, b) [19, 31]. There is also increasing recognition of the desirability of considering biological parameters in the classification of resectability [32, 33]. At the present time however attempted staging by tumour biology is rather crude, using parameters such as CA19-9 levels and lymph node involvement [32, 33]. Given the evolutionary clonality of PDAC accurate tumour biologic staging requires integrating the genotypic (DNA) and phenotypic (mRNA) features of the PDAC tumour necessitating biopsies for sequencing and assessment of tumour microenvironment subtypes [34,35,36]. Liquid biopsies for tumour biotyping and minimal residual disease detection are still at a relatively early stage of evolution but will be of increasing importance with technology advancements [37, 38]. Radical surgery including adequate lymphadenectomy, vascular resection and retroperitoneal clearance is essential to achieving margin-negative resections (R0) and optimising long-term outcomes in patients with empirical classification (Em) resectable (EmR) and borderline resectable (EmBR) disease [39, 40].

a CT image of resectable cancer in the head of the pancreas. b CT image of borderline resectable cancer in the head of the pancreas. c Surgical site after partial pancreato-duodenectomy with venous resection, triangle dissection and splenorenal shunt for borderline rectable disease following induction chemotherapy disease. AA abdominal aorta, CHA common hepatic artery, SMA superior mesenteric artery, HPV hepatic portal vein, SMV superior mesenteric vein, SA splenic artery, IVC inferior vena cava, * hepatic portal vein resection, ** splenorenal shunt, T triangle.

In patients with EmR, the tumour is anatomically resectable, CA19-9 is within an acceptable range and the patient’s performance status supports upfront surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy remains the standard of care [30, 41,42,43]. The precise CA19-9 level favouring surgery is not fully established, although a post-operative upper limit of normal of ≤2.5 as in CONKO-01 or <180 KU/L as in PRODIGE24 are often cited, and according to ESMO guidelines a preoperative serum CA19-9 level ≥500 KU/L indicates a worse prognosis after surgery and immediate surgery should be considered with caution [10, 14, 17, 19]. The operative approach for EmR tumours typically includes partial pancreato-duodenectomy, left (distal) pancreatectomy with splenectomy, or total pancreatectomy, depending on the exact tumour location [44]. In tumours with contact to the coeliac axis or the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), an artery-first approach, via posterior, medial, or inferior approaches, is performed to reduce blood loss, enable early assessment of resectability and to avoid R2 resections [45]. A systematic lymphadenectomy is performed, including complete clearance of lymphatic tissue along the right aspect of the SMA and the coeliac trunk [39, 46]. By achieving an R0 resection in the upfront setting a median overall survival is achieved of 41.6 months with a 5-year survival rate of 37.7% for pancreatic head tumours which is even higher for pancreatic body and tail tumours with 62.4 months and a 5-year survival rate of 52%, respectively [40, 47, 48].

Patients with EmBR tumours often present with anatomical findings such as venous abutment, short-segment involvement of the portal vein or SMV, compression of the SMA, and elevated CA19-9 [49, 50]. Though technically resectable, these tumours are associated with higher risk of R1 resection and early relapse. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy increases survival in this setting irrespective of resectability although surgical resection remains the central potentially curative step in this setting [30, 34]. Surgical resection in EmBR disease frequently involves venous resection and reconstruction and in selected cases, arterial divestment or resection [49, 50]. Besides this the TRIANGLE dissection, involving en bloc skeletonization of the SMA, celiac axis and portal vein has emerged as the benchmark approach for tumours located in the pancreatic head, allowing clearance of perineural and lymphovascular tissue planes commonly harbouring residual disease (Fig. 1c) [51]. To gain high-level evidence for this approach a randomised controlled trial is now ongoing in Germany [52].

Surgical management of resectable and borderline resectable PDAC must be performed in centres with high case volume, multidisciplinary decision-making and excellent perioperative care. Mortality rates for PDAC surgery in such centres have fallen below 5%, and morbidity, although still significant, can be mitigated through standardised pathways (e.g. drain management, early sepsis detection, enhanced recovery). Failure to rescue, defined as mortality after a major complication, is now recognised as a text book outcome benchmark of surgical quality [53]. While more radical surgery including vascular resection and extended dissection may carry increased risk, evidence suggests that when performed in appropriate centres, these techniques do not increase mortality and can significantly improve long-term survival by achieving margin-negative resection in biologically fit patients.

Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy controversy

Whilst the role of adjuvant chemotherapy has been consolidated these past 25 years through well designed randomised trials, the controversy over the role of chemoradiation has never quite settled amongst radiation oncologists especially in the USA (Table 2) [3, 4, 54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. The Radiation oncology Group (RTOG) led by Ross Abrams responded to the ESPAC gamechanger by designing a 2-step adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation trial [61, 62]. This was essentially with a 2 × 2 factorial design that had previously been heavily criticised in ESPAC1 [3, 4]. The RTOG0848 trial initially (step 1) randomised patients to 5 cycles of gemcitabine with or without erlotinib, and if there was no disease relapse patients were then further randomised (step 2) to either a further cycle of gemcitabine or combination chemotherapy or to a further cycle of gemcitabine or combination chemotherapy plus chemoradiation with either capecitabine or 5FU based chemoradiation [61, 62]. Recruitment commenced in 2009, the results of patients randomised in step 1 were published in 2020, and the final results of patients randomised to step 2 were recently reported following complete target accrual in October 2018 (Table 1) [61, 62]. Despite the headline finding that the trial failed to achieve its primary endpoint of improved overall survival with the addition of chemoradiotherapy, it is still being promoted for patients with negative lymph nodes [62]. This small subgroup had a median overall survival of 3.9 years in the chemoradiation group (n = 49) compared to 3.0 years in the chemotherapy group (n = 42), with 5-year overall survival estimates of 48.1% and 28.6% respectively [62]. It is noteworthy that there was no survival benefit for chemoradiation for the patients with positive margins (R1) or positive lymph nodes, yet these are the same exact subgroups that had been advocated for previously as benefitting from chemoradiotherapy [62]. Methodologically it would be difficult to support this specific use given the post hoc nature of the analysis and the prior unspecified application of a one-sided alpha that was used to show significance (p = 0.03) [62]. Contrasting these findings, the ESPAC4 study found that the 5-year overall survival rate for node-negative patients was 59% for patients receiving GemCap and 53% for patients just receiving gemcitabine [18]. The ESMO pancreatic cancer guidelines do not recommend adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and it should not be given to patients following surgery outside the setting of a clinical trial [14]. Understanding the biological basis of the failure of chemoradiotherapy to impact on any improvement in survival in pancreatic cancer is essential in order to determine whether this modality can be used in some way in pancreatic cancer compared to other potentially effective therapies [66,67,68,69].

Neoadjuvant therapy is not superior to adjuvant chemotherapy

Dissipation of the notion that adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was a ‘must have’ in the treatment of pancreatic cancer slowly followed solidification of evidence against its use from 2000 onwards. Pari passu was the emergence of a similar notion that neoadjuvant therapy (including chemoradiotherapy) is a ‘must have’ for all stages of pancreas cancer including resectable pancreatic cancer [70, 71]. This opinionated perception fails to take into account the most modern concept of tumour plasticity which reflects the continuing biological evolution of PDAC, determined by temporal and intrinsic and extrinsic tumour microenvironment pressures, that are quite independent of standard TNM UICC and AJCC classifications [68, 72,73,74,75]. This concept translates into a new understanding that not all pancreatic cancers are the same but are biologically different even though they may appear to be similar macroscopically and histologically. The empirical classification (Em) of resectable (EmR), borderline resectable (EmBR), locally advanced unresectable (EmUR), oligometastatic (EmOM), and polymetastatic (EmPM), equates to a distinct biological transitioning of stages, that requires differing treatment strategies [34, 76]. Thus, an effective therapeutic sequence strategy for one empirical stage cannot automatically be assumed to be applicable to another [32, 74].

Randomised trials demonstrate that whilst neoadjuvant approaches have shown improvement in overall survival in patients with EmBR tumours this has not been the case for patients with EmR tumours (Table 3) [28, 77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. A number of studies (notably PREOPANC1, PREOPANC2, and most recently Prep-02/JSAP05 and CASSANDRA) have caused considerable confusion in interpretation by combining recruitment of patients with both EmR and EmBR tumours and drawing conclusions for both when this might not be the case as in PREOPANC1which showed a neoadjuvant therapy survival benefit in the patients with EmBR tumours but not those with EmR [28, 80, 81, 86, 88]. The Prep-02/JSAP05 trial is a case in point, having originally presented the results at the Asssociation of Clinical Oncolgy Meeting in 2019, the full manuscript has only just now been published [88]. This multicenter trial from Japan recruited 364 patients that were randomly allocated to upfront surgery (n = 182) and were ‘strongly advised’ to take adjuvant S1, or neoadjuvant gemcitabine plus S-1 followed by surgery and also ‘strongly advised’ to take adjuvant S1 (n = 182) [88]. The distinction between EmR and EmBR was ambiguous throughout the manuscript. The primary endpoint itself was ‘to confirm the superiority of neoadjuvant therapy with GS (gemcitabine plus S-1) over the standard strategy of upfront surgery in patients with resectable PDAC.’ Enrolment took place between January 2013 and January 2016, and analysis was undertaken using data collected up to September 2018, 2 years and 9 months after the final enrolment. The median overall survival was 26.6 months (95% CI, 21.5–31.5) in the upfront surgery group and 37.0 months (95% CI, 28.6–43.3) in the neoadjuvant group (p = 0.018) [88]. Critically, the protocol is not available and there is no mention of the statistical analysis plan.

As we know from the ESPAC and the PRODIGE studies, chemotherapy dose intensities are critical in determining overall survival, but this information is lacking in Prep-02/JSAP05 and both groups were ‘strongly advised’ to take adjuvant therapy, but not required to do so [15, 16, 88]. The overall survival results are worse than the JASPAC-01 trial presumably because of the inclusion of patients with EmBR tumours as well as the apparent lower total chemotherapy doses [8, 88]. The overall survival with upfront surgery and ‘advised’ adjuvant S-1 was 26.6 months (95% CI, 21.5–31.5) In JSAP-05 compared to 46·5 months (95% CI, 37·8–63·7) with upfront surgery and required adjuvant S-1 in JASPAC-01; the overall survival with neoadjuvant gemcitabine plus S-1, surgery and advised adjuvant S-1 in JSAP-05 was only 37.0 months (95% CI, 28.6–43.3) [8, 88]. As aforementioned this is where comparing the ‘resected’ patients of adjuvant trials with the ‘resectable’ patients of neo-adjuvant trials is problematic. The authors concluded that ‘The Prep-02/JSAP05 trial results showed that neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus S-1 significantly extends survival compared with upfront surgery in patients with resectable PDAC’ but this statement does not seem to be supported by the data [88]. The Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer 2022 of the Japan Pancreas Society does not strongly recommend this approach [89, 90].

The 2 × 2 factorial CASSANDRA superiority trial was conducted in 260 patients with EmR/EmBR PDAC tumours aged 75 years or less [28]. In the first randomisation patients were enroled to either 4 months induction PAXG (capecitabine, cisplatin, nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine) or to 4 months induction mFOLFIRINOX. Then in the second randomisation they were allocated to either 2 more months of chemotherapy before surgery and no further chemotherapy or surgery followed by 2 months adjuvant chemotherapy. The primary endpoint was event-free survival (EFS) at 3 years defined as one or more of the following: no progression, no recurrence, two consecutive CA19-9 increases by 20% separated by 4 or more weeks, non-resection, intraoperative metastasis and death. The preliminary findings of the first randomisation were presented at ASCO 2025, but for an unspecified reason not the second randomisation. After a median follow-up of 23.9 months, the 3 year median (95% CI) EFS with PAXG was 30% (20, 40) with 14% (5–23) with mFOLFIRINOX with an HR of 0.66 (0.49–0.89; p = 0.005) [28]. The trial however included patients with both EmR (n = 126) and EmBR (n = 134) cancers with 3 year median EFS rates according to the forest plot in the EmR patients of 47.2 vs 22.0% respectively and in the EmBR patients of 18.8 vs 8.9% respectively. The median overall survival in the mixed groups was 37.3 months (26.9-not reached) in the PAXG group and 26.0 months (23.6–39.4) in the mFOLFIRINOX group with an HR of 0.70 (0.47,1.04; P = 0.07) [28]. As well as showing no significant difference for overall survival between the two groups on preliminary analysis, dose intensities were not mentioned in the presentation [28]. The primary endpoint of event free survival as defined in this study does not seem to have been previously validated. There was no control comparator of standard therapy, namely immediate surgery plus adjuvant treatment for the EmR subgroup, and no data on the second randomisation of 2 more months additional chemotherapy prior to surgery versus surgery then 2 months adjuvant chemotherapy therefore indicating differences in, and potentially suboptimal, adjuvant chemotherapy.

The PREOPANC2 trial compared neoadjuvant full-dose FOLFIRINOX but with no scheduled adjuvant chemotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and gemcitabine plus adjuvant gemcitabine in both EmR and EmBR patients with no significant differences in overall survival [86]. In other words, there was no proper control group for the EmR patients which is resection followed by 6 months adjuvant mFOLFIRINOX. Survival estimates for separated resected EmR, EmBR, FOLFIRINOX and chemoradiotherapy groups were not provided preventing inter-trial comparisons.

The recent single centre study from Zhejiang University Hospital, Hangzhou, randomised 324 patients with EmR PDAC to neoadjuvant Gem-NabP plus mFOLFIRINOX or upfront surgery [89]. Patients in the neoadjuvant therapy group received nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine concurrently on days 1, 8 and 15, followed by mFOLFIRINOX on days 29 and 43. Four cycles of adjuvant GemCap were ‘recommended’ in the neoadjuvant group and six cycles of adjuvant GemCap were ‘recommended’ for the upfront surgery group [89]. From 135 patients (83%) resected in the neoadjuvant group 112 patients started adjuvant therapy (69% of those randomised; 83% of those resected) of whom 84 patients (75%) had mFOLFIRINOX and 11 patients (10%) had GemCap. From 149 patients (92%) resected in the upfront surgery group 114 patients started adjuvant therapy (70% of those randomised; 76% of those resected) of whom 86 patients (75%) had mFOLFIRINOX and 10 patients (9%) had GemCap. Only 169 (52%) patients randomized ‘completed’ chemotherapy: 89 patients (55%) in the neoadjuvant group and 80 patients (49%) in the upfront surgery group and most importantly no total dose intensities for either group were provided. The median overall survival was 35.4 months (95% CI, 27.9–45.1) in the neoadjuvant therapy group versus 27.2 months (95% CI, 19.8–33.5) in the upfront surgery group (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.53–1.00; p = 0.0477) [89]. As well as being potentially biased as an open labelled single centre trial and unspecified adjuvant therapy, the conclusions of this trial are further questionable by the short median follow-up (18.7 months, interquartile range 13.0, 32.0), a high proportion of patients with a CA19-9 > 500KU/L (in 138, 43%), an unusually low R0 rate (in 237, 83%) and a very high proportion of left pancreatectomies (in 147, 52%) [89].

Of particular interest is the NORPACT-1 multicenter trial from hospitals in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden, that randomized patients with resectable PDAC to receive either neoadjuvant mFOLFIRINOX (four cycles before surgery then adjuvant chemotherapy) or upfront surgery group (followed by adjuvant chemotherapy) [85]. Initially, adjuvant chemotherapy was GemCap (four cycles in the neoadjuvant group, and six cycles in the upfront surgery group), and was subsequently amended to permit use of adjuvant mFOLFIRINOX (eight cycles in the neoadjuvant group, and 12 cycles in the upfront surgery group) [85]. The primary endpoint was overall survival at 18 months. The proportion of patients alive at 18 months was 60% (95% CI. 49–71) in the 77 patients in the neoadjuvant group versus 73% (95% CI, 62–84) in the 63 patients in upfront surgery group (p = 0·032). The median overall survival was 25·1 months (95% CI, 17·2–34·9) versus 38·5 months (95% CI, 27·6–not reached) respectively, with a hazard ratio of 1·52 (95% CI, 1·00–2·33; p = 0·050). 85 Thus not only was the primary endpoint not reached but patients who underwent upfront surgery with adjuvant chemotherapy had longer survival [85]. Even though it has not been shown beneficial to use a neoadjuvant approach for the EmR group as a whole this does not necessarily rule out that certain biological subgroups of patients—yet to be established—would benefit from a neoadjuvant approach, which future studies should try to address.

Advantages and disadvantages of adjuvant therapy with mFOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine-capecitabine

The long-term follow-up results from both ESPAC4 and PRODIGE 24 have enabled some important information of how these regimens can be used optimally for particular patients [16, 18].

Long-term follow up of 732 patients randomized in the ESPAC4 trial confirmed the overall and relapse-free survival superiority of the gemcitabine-capecitabine combination over gemcitabine. The GemCap combination produced particularly striking survival results in patients with resection margin free (R0) tumours and lymph node negative resections [18]. The gemcitabine-capecitabine combination in R0 patients had a median overall survival of 49.9 months (95% CI, 39.0–82.3) compared to 32.2 months (95% CI, 27.9–41.6) with gemcitabine and a 5 year overall survival of 45% (95% CI, 38–54) versus 31% (95% CI, 25–40) respectively with a hazard ratio of 0.63 (0.47–0.84; p = 0.002) [16]. Interestingly the PRODIGE24 trial found an opposite effect with a non-significant hazard ratio of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.63–1.19) in patients with R0 tumours for mFOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine but with a significant effect in patients with R1 tumours with a hazard ratio of 0.60 (95% CI, 0.43–0.83) [16].

In ESPAC4 patients with lymph node negative tumours had significantly higher 5 year overall survival rates with gemcitabine-capecitabine of 59% (95% CI, 49–71) than gemcitabine showing 53% (95% CI, 42–66), with a hazard ratio of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.41 – 0.98) (p = 0.04) but not those with positive lymph nodes (p = 0.225) [18]. Again, the opposite effect was seen in PRODIGE24 with a non-significant hazard ratio of 1.07 (95% CI, 0.63–1.81) for mFOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine in patients with lymph node negative tumours compared to a significant hazard ratio of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.49–0.81) in patients with lymph node positive tumours [16]. In a sense these findings might be considered to mirror the contrasting effects between these two regimens in advanced disease, with FOLFIRINOX being more effective than gemcitabine in the metastatic setting but not in locally advanced disease whilst gemcitabine-capecitabine seems more effective than gemcitabine in patients with locally advanced disease but less so for metastatic [16, 18, 91,92,93,94]. Note that in the NEOPAN study which randomized patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer to FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine monotherapy, the median progression free survival (the primary end-point) was 9.7 months (95% CI, 7.0–11.7) versus 7.7 months (95% CI, 6.2–9.2) respectively, with a hazard ratio of 0.7 (95% CI, 0.5–1.0; p = 0.04) [94]. On the other hand the median overall survival was 15.7 months (95% CI, 11.9–20.4) in the FOLFIRINOX group compared to 15.4 months (95% CI, 11.7–18.6) in the gemcitabine group with a hazard ratio of 1.02 (95% CI, 0.73–1.43; p = 0.95), somewhat reflecting the findings of the ESPAC5 neoadjuvant randomized trial with not dissimilar overall survival between the GemCap and mFOLFIRINOX groups [94, 95].

In the long term follow-up study of ESPAC4, it was found that the median relapse-free survival rate was 18.3 months (95% CI, 16.3–21.0) in the gemcitabine group and 21.3 months (95% CI, 18.3–24.5) in the gemcitabine-capecitabine group with a hazard ratio of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.72–1.00; p = 0.053) [18]. These results are now very similar to the PRODIGE24 findings with a median disease-free survival of 12.8 months (95%CI, 11.6–15.2) with gemcitabine and 21.4 months (95%CI, 17.5–26.7) with mFOLFIRINOX with a hazard ratio of 0.66 (95%CI, 0.54–0.82; p < 0.001) [16]. It is not clear why the median disease-free survival rates are apparently similar whilst the overall survival rates are disparate, but may relate to greater use of second line therapies in PRODIGE24, and or different biological effects between GemCap and mFOLFIRINOX.

The ESPAC4 long term follow-up study also found significantly improved overall and relapse-free survival for gemcitabine-capecitabine over gemcitabine in the 193 (26.4%) of 732 ESPAC4 patients who would not have been eligible for mFOLFIRINOX using the PRODIGE24 trial criteria [18]. This is a very important finding for standard clinical practice showing that if a patient is not eligible for mFOLFIRINOX then they should be offered gemcitabine-capecitabine rather than gemcitabine since the manageable toxicities of the latter two are comparable yet the overall survival benefits are greater with the gemcitabine-capecitabine combination.

Precision targeting of chemotherapy

Due to tumour heterogeneity and plasticity, it has become apparent that PDAC tumours will respond non-homogeneously to one or other cytotoxic drug regimen [68, 73,74,75]. A variety of transcriptomic signatures have been developed to predict responses to gemcitabine-based versus oxaliplatin-based regimens based on the initial work by David Tuveson and Steve Gallinger that was focused on human derived pancreatic cancer organoids [96]. The PurIST (Purity Independent Subtyping of Tumours) signature is a 16-gene single sample classifier that can distinguish patients more likely to respond to mFOLFIRINOX rather than gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel [97,98,99]. Initial studies have suggested that in advanced PDAC patients with PurIST classical-like tumours and low ECOG scores have longer overall survival with first line mFOLFIRINOX treatment compared to first line gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel [99]. An open-label, phase II study in patients with resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer using PurIST subtyping is allocating patients with classical-like to mFOLFIRINOX and patients with basal-like subtypes to gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT04683315).

The GemPred RNA signature containing thousands of transcripts was derived from preclinical models, but predictions suffered from being associated with the basal-like and classical-like PDAC subtypes [100]. In an attempt to overcome this bias, patient derived pancreatic organoid sequencing data were included in the signature identification strategy, resulting in an ‘Improved GemPred’ signature [100]. This was further refined into the ‘GemCore’ signature containing < 100 transcripts and most recently into an artificial intelligence-driven tool called ‘PancreasView’ incorporating human PDAC stromal sequencing data [101, 102]. A post-hoc analysis of patients in the PRODIGE-24/CCTG PA6 trial showed that the ‘PancreasView’ Instrument could predict 30% of patients receiving gemcitabine monotherapy with comparable survival to those given mFOLFIRINOX, and with fewer adverse events [103]. The gemcitabine response prediction by PancreasView is independent of molecular subtype prediction but not the mFOLFIRINOX prediction [103]. Ongoing prospective studies are aimed at validation (NCT05475366, advanced PDAC, PACsign; NCT06046794, GemCore+ in metastatic PDAC, GemSign-01; NCT06046794, neoadjuvant for EmBR, NeoPREDICT). The GemciTest is a blood-based RNA signature, that measures the expression levels of nine genes using real-time polymerase chain reaction processes, which predicts longer survival in gemcitabine treated patients but not in fluoropyrimidine-based treated patients [104].

The NeoPancOne phase II study of peri-operative mFOLFIRINOX in patients with EmR PDAC, was recently reported at ASCO 2025 [105]. The aim of NeoPancOne is to prospectively investigate the expression levels of the transcription factor GATA6 which can distinguish between classical-like (high GATA6 expression) and basal-like (low GATA6 expression) molecular subtypes [106, 107]. The NeoPancOne study found that disease progression within 6 months occurred in nearly 50% of patients with low tumour GATA6 expression such that neoadjuvant mFOLFIRINOX might no longer be considered the standard of care in these patients [105]. The ESPAC6 randomized European multicenter trial aims to compare standard adjuvant therapy in EmR patients with an experimental arm in which patients are allocated to mFOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine plus capecitabine based on a 236 gene transcriptomic signature (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05314998). The ESPAC signature is unique in having been developed using machine learning exclusively from RNA sequencing of human PDAC tumours.

Precision targeting of chemotherapies is currently and in the foreseeable future very important, since while there is optimism for precision therapy using novel agents, there is still much caution required. Although targeted therapies for PDAC are applicable to perhaps less than 5% of patients at present, remarkable advances are now being made in targeted therapies and immunotherapies, but these novel treatments have yet to show a significant improvement in overall survival [69, 108]. In metastatic pancreatic cancer, despite FDA approval of first line NALIRIFOX (nanoliposomal irinotecan, 5FU and oxaliplatin) based on the NAPOLI trial and olaparib maintenance for patients with germline BRCA variants based on the POLO trial, both trials have been these criticised as producing positive results due to schemed trial design rather than being aimed at improving patient outcomes [109,110,111,112]. It has been strongly argued that the principles governing Common Sense Oncology should form the basis for improving the design, analysis and reporting of randomized controlled phase III clinical trials evaluating cancer treatments, emphasising that control treatment should be the best current standard of care and that the preferred primary endpoint is overall survival or a validated surrogate [113].

Conclusions: main findings and implications

Current practice and future trends are itemised in the Summary Box 1. The NRG Oncology/RTOG 0848 trial from the USA of adjuvant chemotherapy with or without chemoradiation, has shown that the addition of chemoradiation to systemic chemotherapy had no overall survival advantage compared to chemotherapy alone. In particular there was no survival benefit for patients with resection margin positive or lymph node positive tumours.

No randomized trial has shown convincingly that neoadjuvant therapy improves overall survival in patients with resectable as opposed to improved survival in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. The NORPACT-1 trial of neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX versus upfront surgery from the Nordic countries, even showed that there was increased survival in patients that had upfront surgery with adjuvant therapy rather than patients that had neoadjuvant therapy.

Long-term follow-up of the France-Canada PRODIGE24 and the European ESPAC4 trials has confirmed mFOLFIRINOX as the reference standard for adjuvant chemotherapy. We learn however from the ESPAC4 trial that an additional 26% of patients can be treated with gemcitabine-capecitabine (rather than gemcitabine) who are not eligible (or decline) mFOLFIRINOX. Although there was no direct head-to-head comparison mFOLFIRINOX seems to especially benefit patients with resection margin positive or lymph positive tumours, whilst gemcitabine-capecitabine especially benefits patients with resection margin negative or lymph node negative tumours. In the near future molecular signatures may help to further refine selection of induction, neoadjuvant and adjuvant systemic therapies.

References

Neoptolemos JP, Dunn JA, Stocken DD, Almond J, Link K, Beger H, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1576–85.

Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, Bassi C, Dunn JA, Hickey H, et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–10.

Abrams RA, Lillemoe KD, Piantadosi S. Continuing controversy over adjuvant therapy of pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2001;358:1565–6.

Koshy MC, Landry JC, Cavanaugh SX, Fuller CD, Willett CG, Abrams RA, et al. A challenge to the therapeutic nihilism of ESPAC-1. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:965–6.

Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–77.

Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Tudur Smith C, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Owen E, et al. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid vs observation for pancreatic cancer: composite data from the ESPAC-1 and -3(v1) trials. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:246–50.

Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, Ghaneh P, Cunningham D, Goldstein D, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1073–81.

Uesaka K, Boku N, Fukutomi A, Okamura Y, Konishi M, Matsumoto I, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy of S-1 versus gemcitabine for resected pancreatic cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial (JASPAC 01). Lancet. 2016;388:248–57.

Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, Psarelli EE, Valle JW, Halloran CM, et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1011–24.

Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, Ben Abdelghani M, Wei AC, Raoul JL, et al. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2395–406.

Hegewisch-Becker S, Kratz-Albers K, Wierecky J, Gerhardt S, Reschke D, Borchardt J, et al. Current treatment landscape of pancreatic cancer patients in a network of office-based oncologists in Germany. Future Oncol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2022-0141.

Chase M, Friedman HS, Joo S, Navaratnam P. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment patterns among resectable pancreatic cancer patients in the USA. Future Oncol. 2022;18:3929–39.

Tempero MA, Pelzer U, O’Reilly EM, Winter J, Oh DY, Li CP, et al. Adjuvant nab-Paclitaxel + gemcitabine in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: results from a randomized, open-label, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2007–19.

Conroy T, Pfeiffer P, Vilgrain V, Lamarca A, Seufferlein T, O’Reilly EM, et al. Pancreatic cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34:987–1002.

Valle JW, Palmer D, Jackson R, Cox T, Neoptolemos JP, Ghaneh P, et al. Optimal duration and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after definitive surgery for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: ongoing lessons from the ESPAC-3 study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:504–12.

Conroy T, Castan F, Lopez A, Turpin A, Ben Abdelghani M, Wei AC, et al. Five-year outcomes of FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine as adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1571–8.

Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, Hartmann JT, Gellert K, Ridwelski K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310:1473–81.

Palmer DH, Jackson R, Springfeld C, Ghaneh P, Rawcliffe C, Halloran CM, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: long-term outcomes of adjuvant therapy in the ESPAC4 phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:1240–53.

Tempero MA, Malafa MP, Benson AB, Cardin DB, Chiorean EG, Chung V, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®). Version 3.2024, 08/02/2024 © 2024 National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®), NCCN.org.

O’Reilly D, Fou L, Hasler E, Hawkins J, O’Connell S, Pelone F, et al. Diagnosis and management of pancreatic cancer in adults: a summary of guidelines from the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pancreatology. 2018;18:962–70.

Reni M, Macchini M, Orsi G. Is the Delphi’s oracle pertinent to patients with resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma?. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1851.

Pijnappel EN, Suurmeijer JA, Koerkamp BG, Kos M, Siveke JT, Salvia R, et al. Consensus statement on mandatory measurements for pancreatic cancer trials for patients with resectable or borderline resectable disease (COMM-PACT-RB): a systematic review and Delphi consensus statement. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:929–37.

Ahmad SA, Duong M, Sohal DPS, Gandhi NS, Beg MS, et al. Surgical outcome results from SWOG S1505: a randomized clinical trial of mFOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel for perioperative treatment of resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2020;272:481–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004155.

Giannone F, Capretti G, Abu Hilal M, Boggi U, Campra D, Cappelli C, et al. Resectability of pancreatic cancer is in the eye of the observer: a multicenter, blinded, prospective assessment of interobserver agreement on NCCN resectability status criteria. Ann Surg Open. 2021;2:e087. https://doi.org/10.1097/AS9.0000000000000087.

Badgery HE, Muhlen-Schulte T, Zalcberg JR, D’souza B, Gerstenmaier JF, Pickett C, et al. Determination of “borderline resectable” pancreatic cancer—a global assessment of 30 shades of grey. HPB. 2023;25:1393–401.

Reni M, Orsi G. Lessons and open questions in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:101–2.

Reni M, Zanon S, Balzano G, Nobile S, Pircher CC, Chiaravalli M, et al. Selecting patients for resection after primary chemotherapy for non-metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2786–92.

Reni M, Macchini M, Orsi G, Procaccio L, Malleo G, Balzano G, et al. Results of a randomized phase III trial of pre-operative chemotherapy with mFOLFIRINOX or PAXG regimen for stage I-III pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:LBA4004.

Kleeff J, Korc M, Apte M, La Vecchia C, Johnson CD, Biankin AV, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2016;2:16022.

Strobel O, Neoptolemos J, Jäger D, Büchler MW. Optimizing the outcomes of pancreatic cancer surgery. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2019;16:479–92.

Katz MH, Shi Q, Ahmad SA, Herman JM, Marsh RdeW, Collisson E, et al. Preoperative modified FOLFIRINOX treatment followed by capecitabine-based chemoradiation for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: alliance for clinical trials in oncology trial A021101. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:e161137.

Hartwig W, Strobel O, Hinz U, Fritz S, Hackert T, Roth C, et al. CA19-9 in potentially resectable pancreatic cancer: perspective to adjust surgical and perioperative therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2188–96.

Hank T, Hinz U, Reiner T, Malleo G, König AK, Maggino L, et al. A pretreatment prognostic score to stratify survival in pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2022;276:e601–e9.

Neoptolemos JP, Hu K, Bailey P, Springfeld C, Cai B, Miao Y, et al. Personalized treatment in localized pancreatic cancer. Eur Surg. 2024;56:93–109.

Ho IL, Li CY, Wang F, Zhao L, Liu J, Yen EY, et al. Clonal dominance defines metastatic dissemination in pancreatic cancer. Sci Adv. 2024;10:eadd9342.

Kalfakakou D, Cameron DC, Kawaler EA, Tsuda M, Wang L, Jing X, et al. Clonal Heterogeneity in Human Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Its Impact on Tumor Progression. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025 https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.11.637729.

Botta GP, Abdelrahim M, Drengler RL, Aushev VN, Esmail A, Laliotis G, et al. Association of personalized and tumor-informed ctDNA with patient survival outcomes in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2024;29:859–69. Erratum in: Oncologist. 2024 Nov 4;29:e1630.

Lee B, Tie J, Wang Y, Cohen J, Shapiro JD, Wong R, et al. The potential role of serial circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) testing after upfront surgery to guide adjuvant chemotherapy for early stage pancreatic cancer: The AGITG DYNAMIC-Pancreas trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:107.

Strobel O, Hinz U, Gluth A, Hank T, Hackert T, Bergmann F, et al. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: number of positive nodes allows to distinguish several N categories. Ann Surg. 2015;261:961–9.

Strobel O, Hank T, Hinz U, Bergmann F, Schneider L, Springfeld C, et al. Pancreatic cancer surgery: the new R-status counts. Ann Surg. 2017;265:565–73.

Hartwig W, Hackert T, Hinz U, Gluth A, Bergmann F, Strobel O, et al. Pancreatic cancer surgery in the new millennium: better prediction of outcome. Ann Surg. 2011;396:469–80.

Schneider M, Hackert T, Strobel O, Büchler MW. Technical advances in surgery for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2021;5:245–52.

Strobel O, Lorenz P, Hinz U, Gaida M, König AK, Hank T, et al. Actual five-year survival after upfront resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: who beats the odds?. Ann Surg. 2022;275:962–71.

Malleo G, Maggino L, Ferrone CR, Marchegiani G, Luchini C, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. Does site matter? Impact of tumor location on pathologic characteristics, recurrence, and survival of resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2020;272:1080–8.

Müller PC, Müller BP, Hackert T. Contemporary artery-first approaches in pancreatoduodenectomy. BJS Open. 2023;408:261.

Tarantino I, Warschkow R, Hackert T, Schmied BM, Büchler MW, Strobel O, et al. Staging of pancreatic cancer based on the number of positive lymph nodes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:723–31.

Nitschke P, Volk A, Welsch T, Hackl J, Reissfelder C, Rahbari M, et al. Impact of intraoperative re-resection to achieve R0 status on survival in patients with pancreatic cancer: a single-center experience with 483 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:887–93.

Hank T, Hinz U, Tarantino I, Kaiser J, Niesen W, Bergmann F, et al. Validation of at least 1 mm as cut-off for resection margins for pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the body and tail. Ann Surg. 2018;268:411–7.

Bockhorn M, Uzunoglu FG, Adham M, Imrie C, Milicevic M, Sandberg AA, et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: a consensus statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2014;155:977–88.

Hackert T, Klaiber U, Hinz U, Strunk S, Loos M, Strobel O, et al. Portal vein resection in pancreatic cancer surgery: risk of thrombosis and radicality determine survival. Ann Surg. 2023;277:113–21.

Hackert T, Strobel O, Michalski CW, Mihaljevic AL, Mehrabi A, Müller-Stich BP, et al. The TRIANGLE operation – radical surgery after neoadjuvant treatment for advanced pancreatic cancer: a single arm observational study. HPB (Oxf). 2017;19:1001–7.

Heger P, Hackert T, Diener MK, Feißt M, Klose C, Dörr-Harim C, et al. Conventional partial pancreatoduodenectomy versus an extended pancreatoduodenectomy (triangle operation) for pancreatic head cancers—study protocol for the randomised controlled TRIANGLE trial. Trials. 2023;24:400.

Kinny-Köster B, Halm D, Tran D, Kaiser J, Heckler M, Hank T, et al. Who do we fail to rescue after pancreatoduodenectomy? Outcomes among >4000 procedures expose windows of opportunity. Ann Surg. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000006429.

Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Hop WC, Erdmann J, Tran KC, Debois M, et al. Long-term survival and metastatic pattern of pancreatic and periampullary cancer after adjuvant chemoradiation or observation: long-term results of EORTC trial 40891. Ann Surg. 2007;246:734–40.

Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, Safran H, Hoffman JP, Konski A, et al. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1019–26.

Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams R, Safran H, Hoffman JP, Konski A, et al. Fluorouracil-based chemoradiation with either gemcitabine or fluorouracil chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: 5-year analysis of the U.S. Intergroup/RTOG 9704 phase III trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1319–26.

Ueno H, Kosuge T, Matsuyama Y, Yamamoto J, Nakao A, Egawa S, et al. A randomised phase III trial comparing gemcitabine with surgery-only in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japanese Study Group of Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:908–15.

Schmidt J, Abel U, Debus J, Harig S, Hoffmann K, Herrmann T, et al. Open-label, multicenter, randomized phase III trial of adjuvant chemoradiation plus interferon Alfa-2b versus fluorouracil and folinic acid for patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4077–83.

Sinn M, Bahra M, Liersch T, Gellert K, Messmann H, Bechstein W, et al. CONKO-005: Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus erlotinib versus gemcitabine alone in patients after R0 resection of pancreatic cancer: a multicenter randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3330–7.

Sinn M, Liersch T, Riess H, Gellert K, Stübs P, Waldschmidt D, et al. CONKO-006: A randomised double-blinded phase IIb-study of additive therapy with gemcitabine + sorafenib/placebo in patients with R1 resection of pancreatic cancer - Final results. Eur J Cancer. 2020;138:172–81.

Abrams RA, Winter KA, Safran H, Goodman KA, Regine WF, Berger AC, et al. Results of the NRG oncology/RTOG 0848 adjuvant chemotherapy question erlotinib + gemcitabine for resected cancer of the pancreatic head: a phase II randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Oncol. 2020;43:173–9.

Abrams RA, Winter KA, Goodman KA, Regine R, Safran H, Berger AC, et al. NRG Oncology/RTOG 0848: Results after adjuvant chemotherapy +/- chemoradiation for patients with resected periampullary pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PA). J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:4005.

Twombly R. Adjuvant chemoradiation for pancreatic cancer: few good data, much debate. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1670–1.

Merchant N, Berlin J. Past and future of pancreas cancer: are we ready to move forward together?. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3478–80.

Palmer DH, Jackson RJ, Springfeld C, Hackert T, Michalski CW, Neoptolemos JP. Reply to: adjuvant treatment options and modalities in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: insights from ESPAC4. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:2229–30.

Seifert L, Werba G, Tiwari S, Giao Ly NN, Nguy S, Alothman S, et al. Radiation therapy induces macrophages to suppress t-cell responses against pancreatic tumors in mice. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1659–72.

Lee SY, Jeong EK, Ju MK, Jeon HM, Kim MY, Kim CH, et al. Induction of metastasis, cancer stem cell phenotype, and oncogenic metabolism in cancer cells by ionizing radiation. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:10.

Hwang WL, Jagadeesh KA, Guo JA, Hoffman HI, Yadollahpour P, Reeves JW, et al. Single-nucleus and spatial transcriptome profiling of pancreatic cancer identifies multicellular dynamics associated with neoadjuvant treatment. Nat Genet. 2022;54:1178–91.

Hu ZI, O’Reilly EM. Therapeutic developments in pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;21:7–24.

Hall WA, Dawson LA, Hong TS, Palta M, Herman JM, Evans DB, et al. Value of Neoadjuvant radiation therapy in the management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:3773–7.

Cucchetti A, Djulbegovic B, Crippa S, Hozo I, Sbrancia M, Tsalatsanis A, et al. Regret affects the choice between neoadjuvant therapy and upfront surgery for potentially resectable pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2023;173:1421–7.

Notta F, Chan-Seng-Yue M, Lemire M, Li Y, Wilson GW, Connor AA, et al. A renewed model of pancreatic cancer evolution based on genomic rearrangement patterns. Nature. 2016;538:378–82.

Chan-Seng-Yue M, Kim JC, Wilson GW, Ng K, Figueroa EF, O’Kane GM, et al. Transcription phenotypes of pancreatic cancer are driven by genomic events during tumor evolution. Nat Genet. 2020;52:231–40.

Grünwald BT, Devisme A, Andrieux G, Vyas F, Aliar K, McCloskey CW, et al. Spatially confined sub-tumor microenvironments in pancreatic cancer. Cell. 2021;184:5577–92.e18.

Zhou X, An J, Kurilov R, Brors B, Hu K, Peccerella T, et al. Persister cell phenotypes contribute to poor patient outcomes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in PDAC. Nat Cancer. 2023;4:1362–81.

Springfeld C, Ferrone CR, Katz MHG, Philip PA, Hong TS, Hackert T, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:318–37.

Golcher H, Brunner TB, Witzigmann H, Marti L, Bechstein WO, Bruns C, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy with gemcitabine/cisplatin and surgery versus immediate surgery in resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the first prospective randomized phase II trial. Strahlenther Onkol. 2015;191:7–16.

Casadei R, Di Marco M, Ricci C, Santini D, Serra C, Calculli L, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy and surgery versus surgery alone in resectable pancreatic cancer: a single-center prospective, randomized, controlled trial which failed to achieve accrual targets. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1802–12.

Reni M, Balzano G, Zanon S, Zerbi A, Rimassa L, Castoldi R, et al. Safety and efficacy of preoperative or postoperative chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PACT-15): a randomised, open-label, phase 2-3 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3:413–23.

Versteijne E, Suker M, Groothuis K, Akkermans-Vogelaar JM, Besselink MG, Bonsing BA, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy versus immediate surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the dutch randomized phase III PREOPANC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1763–73.

Versteijne E, van Dam JL, Suker M, Janssen QP, Groothuis K, Akkermans-Vogelaar JM, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus upfront surgery for resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: long-term results of the dutch randomized PREOPANC trial. J Clin Oncol: J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2022;40:1220–30.

Sohal DPS, Duong M, Ahmad SA, Gandhi NS, Beg MS, Wang-Gillam A, et al. Efficacy of perioperative chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:421–7.

Seufferlein T, Uhl W, Kornmann M, Algul H, Friess H, Konig A, et al. vgb or only adjuvant gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel for resectable pancreatic cancer (NEONAX)—a randomized phase II trial of the AIO pancreatic cancer group. Ann Oncol: J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2023;34:91–100.

Schwarz L, Bachet JB, Meurisse A, Bouché O, Assenat E, Piessen G, et al. Neoadjuvant FOLF(IRIN)OX chemotherapy for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: multicenter randomized noncomparative phase II trial (PANACHE01 FRENCH08 PRODIGE48 study). J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:1984–96.

Labori KJ, Bratlie SO, Andersson B, Angelsen JH, Biörserud C, Björnsson B, et al. Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX versus upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic head cancer (NORPACT-1): a multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:205–17.

Janssen QP, van Dam JL, van Bekkum ML, Bonsing BA, Bos H, Bosscha KP, et al. Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX versus neoadjuvant gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy in resectable and borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (PREOPANC-2): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2025;26:1346–56.

Goetze TO, Reichart A, Bankstahl US, Pauligk C, Loose M, Kraus TW, et al. Adjuvant gemcitabine versus neoadjuvant/adjuvant FOLFIRINOX in resectable pancreatic cancer: the randomized multicenter phase II NEPAFOX trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:4073–83.

Unno M, Motoi F, Matsuyama Y, Satoi S, Toyama H, Matsumoto I, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and S-1 versus upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer: results of the randomized phase II/III Prep-02/JSAP05 trial. Ann Surg. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000006730.

Bai X, Li X, Chen Y, Qiao G, Zhang Q, Ma T, et al. Neoadjuvant nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine followed by modified FOLFIRINOX for resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomized phase 3 trial. Cancer Cell. 2025;43:1–9.

Okusaka T, Nakamura M, Yoshida M, Kitano M, Ito Y, Mizuno N, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pancreatic Cancer 2022 from the Japan Pancreas Society: a synopsis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2023;28:493–511.

Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, Valle JW, Smith D, Steward W, et al. Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5513–8.

Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouché O, Guimbaud R, Bécouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–25.

Ozaka M, Nakachi K, Kobayashi S, Ohba A, Imaoka H, Terashima T, et al. A randomised phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (JCOG1407). Eur J Cancer. 2023;181:135–44.

Ducreux M, Desgrippes R, Rinaldi Y, Di Fiore F, Guimbaud R, Evesque L, et al. PRODIGE 29-UCGI 26 (NEOPAN): a phase III randomized trial comparing chemotherapy with FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine in locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2025;43:2255–64.

Ghaneh P, Palmer D, Cicconi S, Jackson R, Halloran CM, Rawcliffe C, et al. Immediate surgery compared with short-course neoadjuvant gemcitabine plus capecitabine, FOLFIRINOX, or chemoradiotherapy in patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer (ESPAC5): a four-arm, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:157–68.

Tiriac H, Belleau P, Engle DD, Plenker D, Deschênes A, Somerville TDD, et al. Organoid profiling identifies common responders to chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1112–29.

Rashid NU, Peng XL, Jin C, Moffitt RA, Volmar KE, Belt BA, et al. Purity independent subtyping of tumors (PurIST), a clinically robust, single-sample classifier for tumor subtyping in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:82–92.

Li Y, Merker JD, Kshatriya R, Trembath DG, Morrison AB, Kuhlers PC, et al. Purity independent subtyping of tumors (purist) pancreatic cancer classifier: analytic validation of a 16-RNA expression signature distinguishing basal and classical subtypes. J Mol Diagn. 2024;26:962–70.

Wenric S, Davison JM, Guittar J, Mayhew GM, Beebe K, Zander A, et al. Real-world validation of the PurIST classifier demonstrates enhanced therapy selection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients. Cancer Res. 2024;84:2542.

Nicolle R, Gayet O, Duconseil P, Vanbrugghe C, Roques J, Bigonnet M, et al. A transcriptomic signature to predict adjuvant gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:250–60.

Nicolle R, Gayet O, Bigonnet M, Roques J, Chanez B, Puleo F, et al. Relevance of biopsy-derived pancreatic organoids in the development of efficient transcriptomic signatures to predict adjuvant chemosensitivity in pancreatic cancer. Transl Oncol. 2022;16:101315.

Fraunhoffer N, Chanez B, Teyssedou C. A transcriptomic-based tool to predict gemcitabine sensitivity in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:476–80.

Nicolle R, Bachet JB, Harlé A, Iovanna J, Hammel P, Rebours V, et al. Prediction of adjuvant gemcitabine sensitivity in resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma using the GemPred RNA signature: an ancillary study of the PRODIGE-24/CCTG PA6 clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42:1067–76.

Piquemal D, Bruno R, Bournet B, Ghiringhelli F, Noguier F, Canivet C, et al. Performance of a blood-based RNA signature for gemcitabine-based treatment in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2023;14:997–1007.

McLaughlin RM, Jonker DJ, Karanicolas PJ, Ko Y-J, Welch S, Renouf DJ, et al. NeoPancONE: GATA6 expression as a predictor of benefit to peri-operative modified FOLFIRINOX in resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma (r-PDAC): a multicentre phase II study. J Clin Oncology 2025;43:4011.

O’Kane GM, Grünwald BT, Jang GH, Masoomian M, Picardo S, Grant RC, et al. GATA6 expression distinguishes classical and basal-like subtypes in advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4901–10. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3724. Epub 2020 Mar 10. Erratum in: Clin Cancer Res. 2022; 28:2715.

Knox JJ, Jang GH, Grant RC, Zhang A, Ma L, Elimova E, et al. Whole genome and transcriptome profiling in advanced pancreatic cancer patients on the COMPASS trial. Nat Commun. 2025;16:5919.

Reiss KA, Soares KC, Torphy RJ, Gyawali B. Treatment innovations in pancreatic cancer: putting patient priorities first. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2025;45:e473204.

Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, Van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:317–27.

Wainberg ZA, Melisi D, Macarulla T, Pazo Cid R, Chandana SR, De La Fouchardière C, et al. NALIRIFOX versus nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine in treatment-naive patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (NAPOLI 3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402:1272–81.

M’Baloula J, Tougeron D, Boilève A, Jeanbert E, Guimbaud R, Ben Abdelghani M, et al. Olaparib as maintenance therapy in non resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma associated with homologous recombination deficiency profile: a French retrospective multicentric AGEO real-world study. Eur J Cancer. 2024;212:115051.

Gyawali B, Booth CM. Treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer: 25 years of innovation with little progress for patients. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25:167–70.

Gyawali B, Eisenhauer EA, van der Graaf W, Booth CM, Cherny NI, Goodman AM, et al. Common Sense Oncology principles for the design, analysis, and reporting of phase 3 randomised clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2025;26:e80–e89.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All of the authors contributed equally to the development of the concepts of the review. JPN prepared the first draft with subsequent edits and contributions by all of the co-authors. T. Hackert provided the CT scans. Thomas Hank provided the operative figure.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

CS declares advisory board membership for Astra Zeneca, Bayer, BMS, Roche, Incyte, MSD, Revolution Medicines, Servier and Taiho. DHP declares advisory board membership and consultancy for MSD, BMS, AZ, Sirtex, Taiho, Jazz, Viatris, Nucana, Medannex, Servier, and Pfizer; Research Grant Funding from BMS, Sirtex, Nucana, and Medannex. JPN declares advisory board membership for BioNTech (BNT32), and the patent 52378-704.601 PCT 23 May 2025, Combination of Irinotecan and AP-001 for treating cancer. T. Hackert, DÖ, TP, T. Hank, MWB and CWM declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All of the authors approved the final manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Springfeld, C., Hackert, T., Palmer, D.H. et al. New implications from long-term outcomes of perioperative therapy in resectable pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 134, 531–542 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03295-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03295-9