Abstract

Aberrant mucin expression is implicated in lower gastrointestinal tract (GIT) cancers, yet its clinicopathological relevance remains poorly understood. To identify distinct mucin signatures in association with (pre)tumour subtypes, anatomical location, and clinical outcomes, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of MEDLINE articles published between January 2001 and September 2025. Studies were included if they assessed mucin expression in lower GIT (pre)malignant lesions. Fifty-eight studies were eligible. MUC2 and MUC5AC expression was upregulated in serrated polyps and mucinous- and microsatellite instability (MSI)-associated proximal adenocarcinomas, whereas a downregulation of MUC2 was noted in advanced adenomas and non-mucinous distal tumours. Discrepancies in survival in relation to high-level or low-level MUC2 further suggested that this glycoprotein cooperates with other mucins during carcinogenesis. Notably, abundant MUC1 expression was seen in adenomas with high-grade dysplasia and together with high-level MUC13 correlated with (non-)mucinous CRC types and poor prognosis. Similar mucin signatures were also found in small intestinal adenocarcinoma, yet MUC2 was downregulated and increased MUC5AC rather associated with a worse survival, emphasizing the role of tumour location in influencing tumour behaviour. In conclusion, aberrant mucin signatures reflect distinct molecular pathways in (pre)malignant GIT lesions and highlight their potential utility as biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

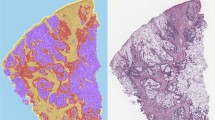

Schematic representation of the main findings regarding altered mucin signalling in several precancerous lesions (adenomatous (i.e., conventional pathway 1) and serrated polyps (i.e. pathway 2)) and small intestinal (SIA) and colorectal (CRC) adenocarcinomas and its clinicopathological significance (outcome, anatomical location (proximal/distal), molecular subtypes (MSI, (non)-mucinous).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. The 5-year survival is 70% in stage I disease but drops enormously to 12% in metastatic cases [1]. Most CRC cases are sporadic adenocarcinomas developing slowly over several decades through a multistep process starting from benign adenomatous polyps (i.e., tubular or tubulovillous adenoma) on the inner wall of the colon and rectum and further develop into an advanced adenoma and carcinoma in situ, invasive carcinoma, and eventually distant metastases [2]. Additionally, non-adenomatous polyps (i.e., hyperplastic polyps) may develop into serrated adenomas, an aggressive type of adenoma and another precursor lesion that can develop into CRC through BRAF mutations [2]. Several subtypes of CRC can be differentiated. These include microsatellite instable (MSI) and stable (MSS) subtypes, consensus molecular subtypes (CMS1-CMS4) based on bulk RNA sequencing profiles, and two major intrinsic epithelial subtypes (iCMS2-iCMS3) based on single-cell RNA sequencing profiles [3]. Furthermore, the anatomical location (rectum, left- (distal) and right-sided (proximal)), somatic mutational (e.g., APC, KRAS, BRAF, TP53) and epigenetic profiles (e.g., high-level CpG island methylator (CIMP-H)), mucinous (accounting for 10–15% of the CRC cases) and non-mucinous phenotypes, also add to the large heterogeneity of CRC [4]. Primary adenocarcinoma can also occur in the small intestine and are often detected in advanced stages, compromising survival times [5].

One of the hallmark features of adenocarcinomas is aberrant mucin (MUC) expression, which drives the transition from inflammation towards cancer and has been linked to the initiation, progression, and poor prognosis [6]. Mucins are the gatekeepers of the mucus barrier covering the epithelium underneath and are heavily glycosylated. They are expressed at the apical surfaces of epithelial cells either as secretory or transmembrane mucins [7]. Besides having a protective function, transmembrane mucins also participate in intracellular signal transduction and play an important role in epithelial cell homeostasis [7]. The intestinal epithelium represents thus a defensive barrier by carrying out several critical functions including mucin expression and maintaining a tight physical barrier via the regulation of controlled cell death [7].

During carcinogenesis, however, aberrant mucin expression contributes to a dysfunctional mucus barrier, dysregulated programmed cell death, and ultimately cancer development [6, 7]. Mucin expression and distribution vary considerably in CRC with transmembrane mucins being often redistributed across the entire tumour cell membrane, thereby promoting cell growth and survival [6, 7]. Furthermore, inhibition of aberrant mucin expression may sensitize tumour cells to chemotherapeutics, highlighting their potential as attractive novel targets for cancer treatment [8]. Yet, the clinical importance of aberrant mucin expression in intestinal-type adenocarcinomas still remains inconsistent in the context of clinicopathological factors, such as disease outcome. We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of available studies evaluating mucin expression in patients with adenocarcinomas of the lower gastrointestinal tract (GIT) or their precursor lesions compared to controls to better define the clinical significance of aberrant mucin expression in relation to survival rate, tumour subtypes, and anatomical location in the intestinal tract.

Methods

Search strategy

A search of the online bibliographic database MEDLINE was carried out by two independent researchers to identify articles published between January 2001 and September 2025, according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) statement [9]. The following search terms were used: lower gastrointestinal tract, colorectal, small intestines, intestinal diseases, tumour, cancer, carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, adenoma, polyp, mucin, transmembrane, secreted, MUC1, MUC2, MUC3, MUC3A, MUC3B, MUC4, MUC5AC, MUC5B MUC6, MUC7, MUC9, MUC12, MUC13, MUC14, MUC15, MUC16, MUC17, MUC18, MUC19, MUC20, MUC21, immunohistochemistry (IHC), RT-qPCR, microarray, FISH. Synonyms and word variations were combined using the AND and OR function. The following negative search terms were also added to exclude the following organ systems and diseases: duodenum, genitourinary system, respiratory system, liver, pancreas, inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, infections.

Eligibility assessment

Two authors (AVM and JG) independently reviewed studies, extracted the data and organized it into a spreadsheet. Studies (i.e., cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies) were included if they examined mucin expression in intestinal tissue samples obtained via surgical resection or endoscopy from patients of any age with adenocarcinoma or precancerous lesions of the lower GIT. The Newcastle and Ottawa scale was used for assessing quality of the included studies [10]. Studies without focus on mucins, the lower GIT and/or neoplastic growth as well as animal studies and in vitro studies were excluded. Studies that failed to provide a description of the methodology or with a quality score lower than 4 were also excluded.

Data extraction

The data collected included the following: patient characteristics (country, sample type (control or (pre-)tumour (sub)type (mucinous vs non-mucinous, microsatellite instability)) and number, tumour stage, survival rate, anatomical location (ileum, proximal/distal colon or rectum)), mucin expression assessment method, mucin type (transmembrane or secreted; gastric (MUC5AC and MUC6) or intestinal) and mucin expression differences between groups with significant P-value < 0.05.

Meta-analysis

From eligible studies, data were extracted from univariate Kaplan-Meier curves using WebPlotDigitizer (automeris.io) and individual patient data reconstructed using the IPDfromKM R-package (v. 0.1.10) [11]. To estimate the hazards ratio (HR) and associated standard error (SE(HR)), a univariate Cox-Proportional Hazards model was fitted. All models compared the low expression group to the high expression group of a certain mucin to evaluate the association between aberrant expression of a specific mucin type and survival outcomes, i.e., overall survival (OS) and cancer-specific survival (CSS). Final generic inverse variance meta-analysis was performed using meta R-package (v. 8.2-1). A random effects model was fitted to estimate pooled effect and it’s 95% confidence interval. Forest plots were constructed to visualize HRs of individual studies as well as the pooled HR for each mucin investigated. A pooled HR > 1 indicated a worse prognosis in patients with high expression of the investigated mucin, whereas a pooled HR ≤ 1 suggested a better outcome. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the χ2, with alpha set at 0.1, I² statistic for estimating magnitude of heterogeneity and τ2 for between study variance estimation, while potential publication bias was examined with Begg’s funnel plots and Egger’s linear regression test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate significant publication bias. Meta-analysis was performed using the meta package in R (RStudio) including at least 2 eligible studies investigating survival endpoints in relation to aberrant expression of a certain mucin type.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The literature search identified 322 records that were screened against title and abstract and from this excluded 226 studies. Ninety-one studies were assessed for full-text eligibility (Fig. 1). Of these, 58 studies were retained, including 49 evaluating mucin expression in adenocarcinomas (i.e., 37 in CRC, 5 in intestinal adenocarcinomas, and 7 in rare tumours) and 16 in benign precursor lesions. Seven out of 58 investigated mucin expression in both benign and malignant lesions (Fig. 1). The majority of papers investigated mucin expression by immunohistochemical staining while a minority used RNA-based approaches (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Among the 58 articles reviewed, MUC2 was the most frequently investigated mucin as its expression was explored in 41 studies (Fig. 2a–f). MUC5AC was the second most often studied mucin, being described in 37 studies followed by MUC1 (26 studies) and MUC6 (19 studies; Fig. 2a–f). Co-expression of MUC1, MUC2 and MUC5AC was also often studied, as visualized in the upset plots and network charts (Fig. 2a–d). A detailed summary of the included studies can be found in Supplementary Tables S1–S3, whereas an overview of the number of mucins investigated per study and the total number of studies investigating each lesion type are depicted in Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3. Most studies (53%) assessed mucin expression in tissue samples from Asian populations, but North-American (12%), European (25%), North-African (5%), and Australian (4%) populations were also explored (Supplementary Tables S1–S3 and Fig. S4).

a, b Upset plots visualizing mucin distribution in benign precursor lesions (a) and malignant tumours (b). Each bar above the matrix represents the number of studies that examined a specific mucin signature. c, d Mucin network charts for benign precursor lesions (c) and malignant tumours (d). The number between brackets indicates how many times a mucin was investigated in the included studies and represents the thickness of the dots. The thickness of each line represents how often mucins were co-examined. e, f Sankey chart visualizing the distribution of mucins across the various types of precancerous lesions (adenomatous and serrated polyps) (e) and adenocarcinomas (colorectal cancer (CRC), small intestinal adenocarcinoma (SIA) and rare tumours) (f). The width of each flow indicates how frequently a mucin is investigated in a (pre)malignant lesion type and the number between brackets indicates the number of studies investigating a mucin in a (pre)malignant lesion type.

Mucin alterations in benign precursor lesions of CRC

Serrated polyps

Eleven studies examined mucin expression in serrated polyps (Fig. 2e; Supplementary Table S1). There was an overall consensus that the expression of the secreted mucins MUC2 and MUC5AC was significantly increased in serrated polyps (Fig. 3b) [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Although MUC5AC is a gastric mucin type with low-level intestinal expression (Fig. 3a), this glycoprotein is aberrantly expressed in the upper segment of crypts near the luminal cell surface in serrated polyps [13, 14]. Furthermore, MUC5AC hypomethylation, which impacts the MUC5AC gene promotor and thus its expression level, was also more frequently detected in serrated polyps harbouring BRAF mutations, CIMP-H and/or MSI phenotypes [17]. By comparison, MUC2 hypomethylation was seen in polyps harbouring or lacking oncogenic mutations and correlated with the proximal colonic location in microvesicular hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated lesions [17]. Additionally, expression of MUC6, another gastric mucin that is absent in the normal intestinal mucosa (Fig. 3a), is also increased in serrated polyps and predominantly in sessile serrated lesions and traditional serrated adenomas from the proximal colon (Fig. 3b) [14, 18,19,20]. Regarding the transmembrane mucins, expression of MUC1 seems to be increased in sessile serrated lesions, whereas a reduced expression was noted in hyperplastic polyps (Fig. 3b). This study also revealed that positive IHC staining for MUC1 and MUC6 and negative IHC staining for MUC2 in colorectal polyps associated with an increased risk of invasion in the mucosa or muscularis mucosae [18]. Besides, one study found a positive MUC13 staining in hyperplastic polyps (Fig. 3b), albeit with a sample size of two polyps [21].

a Mucin distribution in normal colon. b Mucin distribution in precancerous lesions and their subtypes (serrated polyps: hyperplastic polyps (HP), sessile serrated lesions (SSL), traditional serrated adenomas (TSA); adenomatous polyps: tubular adenomas (TA), villous adenomas (VA), tubulovillous adenomas (TVA)). c Mucin distribution in small intestinal (SIA) and colorectal (CRC) adenocarcinoma and their subtypes. d Mucin distribution in intestinal rare tumour types. For each study, the number of a (pre)cancerous lesion type showing expression of a specific mucin were pooled across all studies examining the same mucin in the same lesion type, resulting in an overall proportion (%) of lesions with aberrant expression of a certain mucin. Expression levels were also compared to those in normal intestinal tissue (if available): green indicates higher expression and red indicates lower expression relative to normal colon. If no comparison with healthy tissue was available, dots are highlighted in grey. If no data were available for a specific mucin in a given lesion subtype, no dot is shown.

Adenomatous polyps and progression towards adenocarcinoma

Eight studies investigated mucin expression in adenomatous polyps (Fig. 2e; Supplementary Table S1). They also found significant higher expression levels of MUC2 and MUC5AC (Fig. 3b) albeit with a lower IHC staining intensity compared to what has been described in serrated polyps [15, 22, 23]. Additionally, MUC5AC hypomethylation seems to be absent in conventional adenomas [15, 16, 23]. Expression of the secreted MUC5B and MUC6 mucins was evident in only a fraction of adenomas, i.e., 27% and 10%, respectively [12], whereas the presence of the transmembrane MUC1 and MUC17 mucins was overall more pronounced in these precursor lesions [12]. Furthermore, multivariate regression analyses showed that aberrant MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC17 signatures have the potential to discriminate between adenoma-adenocarcinoma progression and hyperplastic polyps [12], while other studies highlighted that high-level MUC1 and low-level MUC2 expression (Fig. 3b) correlates with a more severe precursor lesion and progression towards adenocarcinoma [24, 25]. More specifically, expression of MUC1 is low in the healthy intestinal mucosa (Fig. 3a) and in adenomas with mild to moderate dysplasia whereas its expression level significantly increased with the grade of dysplasia and further progression towards adenocarcinoma. The opposite was however seen for MUC2. This intestinal-type secreted mucin is abundantly secreted by intestinal goblet cells in the healthy mucosa (Fig. 3a), but its expression decreases in adenomas with mild dysplasia and is even lower in adenomas with moderate and severe dysplasia [24].

Clinical significance of aberrant mucin signatures in colorectal adenocarcinomas

A significant loss of MUC2 expression in CRC adenocarcinomas compared to normal colorectal tissues was reported in most of the included studies (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Table S2) [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] and such tumours particularly originated from the distal (left-sided) colon and rectum. On the contrary, significant increased MUC2 expression was also described in CRC adenocarcinomas, specifically in the mucinous CRC subtypes (Fig. 3c) that arose in the proximal (right-sided) colon [26, 28, 33,34,35,36,37,38]. Regarding CRC outcome, low-level MUC2 significantly correlated with a poor overall survival in CRC, disease recurrence and disease progression, whereas high-level MUC2 was rather linked to a longer disease-free survival in patients with CRC of any tumour stage [31, 32, 34, 39,40,41]. However, others highlighted that the overall 3-year survival is significantly improved in mucinous adenocarcinoma with low-level MUC2 than high-level MUC2 [42]. This discrepancy in survival between high and low MUC2 expression was also reflected in the meta-analysis, which found no significant association between MUC2 expression and overall survival (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S11). A significant association between low-level MUC2 and worse outcome when investigating cancer-specific data was however, seen (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Figs. S7, S9). Of note, the pooled studies did not distinguish between mucinous and non-mucinous adenocarcinomas. Several studies also reported de novo expression of MUC5AC in CRC adenocarcinomas [12, 35, 43,44,45,46]. Interestingly, MUC5AC hypomethylation associated with high MUC5AC expression and together with aberrant MUC2 expression, are linked to the MSI CRC subtype [28]. Furthermore, high-level MUC5AC expression correlated with the proximal tumour location, an increased overall survival (as supported by the meta-analysis; Fig. 4c; Supplementary Figs. S10, S12), longer progression-free survival, improved disease free survival and a decreased risk of recurrence or metastatic disease in the post-operative period [34, 43, 47]. MUC5B, highly expressed in the lower crypts of the healthy colon, was not significantly altered in CRC tumours compared to their normal counterparts [12, 44], although its expression was associated with the presence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and mucinous differentiation [35]. Similarly to MUC5AC, MUC6 is significantly upregulated in CRC (Fig. 3c) [34, 35] and correlated with the presence of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes, proximal colonic location, mucinous tumour differentiation, and 100% progression-free survival (Supplementary Table S2) [34, 35].

For each analysis the low expression level was set as a reference. The following analysis were performed: overall survival (OS) for MUC2 expression (a); cancer specific survival (CSS) for MUC2 expression (b); OS for MUC5AC expression (c); OS for MUC1 expression (d) and CSS for MUC1 expression (e). The size of the boxes are related to the weight of each study in the pooled HR estimate of the random effects model. The full line indicates HR = 1 or no difference in survival between both groups, while the dotted line indicates the estimated pooled HR. Heterogeneity measures I2 and τ2 are reported for each analysis and a χ2 test was performed (p < 0.1 indicates significant heterogeneity between study findings). Significance of the random effects model pooled hazards ratio was tested using the Z-test (z-score and associated p-value).

Regarding transmembrane mucin expression, a significant heterogeneity in the included studies investigating MUC1 expression was noted. Whereas some stated that MUC1 expression was not detectable in the healthy mucosa [48,49,50] compared to others, all studies highlighted a significant increased MUC1 expression in CRC (Fig. 3c), albeit with a variability in MUC1 positive staining [43]. MUC1 expression also positively correlated with the development of high-grade dysplasia, tumour stage (i.e., pTNM and pM, but not pN), and the depth of tumour, lymphatic and venous invasion [25, 34, 51,52,53]. Well and moderately differentiated CRC adenocarcinomas seemed to have a significantly lower MUC1 expression than poorly differentiated CRC tumours whereas significant increased MUC1 expression can occur in both mucinous and non-mucinous tumour subtypes (Fig. 3c) [24,25,26, 30, 34, 54]. One study, investigating the difference in MUC1 expression between the tumour centre and invasion front, even highlighted that the intensity of MUC1 expression was the strongest in the tumour centre of poorly differentiated CRCs [39]. Furthermore, increased MUC1 expression significantly associated with worse overall and cancer-specific survival (as supported by the meta-analysis; Fig. 4d, e; Supplementary Figs. S5, S6, S8, S13), depending on the cellular location (i.e., cytoplasm versus apical staining) [51, 55], as well as with poorer post-operative survival in CRC tumours showing stromal-dominant MUC1 staining [55]. One study reported aberrant MUC3 expression in 84% of the investigated CRC tumours [56], whereas others [12] highlighted a significant increase in MUC4 expression in mucinous adenocarcinomas (Fig. 3c). MUC13, a predominant transmembrane mucin expressed in the normal colorectal epithelium and mainly by columnar epithelial cells (Fig. 3a), is aberrantly expressed (Fig. 3c) in the cytoplasm of CRC tumour cells [21]. Such high cytoplasmic MUC13 expression associated with poorly differentiated and late-stage tumours, specifically of the non-mucinous left-sided tumour subtype, and worse overall survival [21]. Other studies further described a reduced MUC12 and MUC15 expression in CRC tumours (Fig. 3c) [57, 58], whereas significant increased MUC20 expression also associated with poor prognosis in CRC (Supplementary Table S2; Fig. 3c) [59].

Clinical significance of aberrant mucin signatures in small intestinal adenocarcinomas

In total, 5 studies investigated mucin expression in adenocarcinomas of the middle (jejunum) and distal part (ileum) of the small intestine (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table S2) [52, 60,61,62,63]. A significant loss of MUC2 expression was described in small intestinal adenocarcinomas (Fig. 3c) and occurred more often in this type of malignancy compared to CRC adenocarcinomas [52, 60]. Furthermore, loss of this secreted glycoprotein was also linked to the tumour’s behaviour as its expression level negatively associated with lymphatic invasion, tumour size and non-mucinous, poorly differentiated tumours (Supplementary Table S2) [60]. Also a significant increase in MUC5AC expression was noted in a large amount of small intestinal adenocarcinoma samples compared to non-neoplastic intestinal epithelium (Fig. 3c), albeit at a lower frequency compared to CRC tumours [52, 60]. Regarding associations with clinicopathological findings, increased MUC5AC expression positively correlated with low-grade tumours, poor prognosis, lymph node metastasis and MSI in combination with low MUC2 secretion (Supplementary Table S2) [61, 62]. Small intestinal tumours with high MUC6 expression were associated with lymph node metastasis [60], whereas other studies reported that MUC6-positive tumours were more often characterized by a lower T-classification (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table S2) [61]. Whereas a significant increase of MUC1 expression was found in small intestinal adenocarcinomas, particularly in poorly differentiated tumours, no clear difference in MUC4 and MUC16 expression was seen compared to the normal intestinal mucosa (Fig. 3c) [52, 60, 61]. Furthermore, expression of MUC1 and MUC16 was also higher in cases with deeper invasion depth and venous invasion and their expression level positively correlated with a poor outcome (Supplementary Table S2) [60, 61, 63].

Mucin expression in other rare adenocarcinomas of the lower GIT

Aberrant expression of MUC1, MUC2, and MUC5AC has also been described in colonic signet-ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) (Fig. 3d) [64]. Expression of MUC1 and MUC2 was not significantly different in medullary colon carcinoma, compared to poorly differentiated colonic carcinoma (Fig. 3d) [65]. Furthermore, colorectal adenocarcinomas with enteroblastic differentiation (CAED) and high-level MUC5AC tend to have larger tumour masses and originate from the right side of the colon [66]. Finally, different types of mucinous appendiceal neoplasms, namely low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) and mucinous appendiceal adenocarcinoma, have also shown to positively correlate with increased MUC2 and MUC5AC expression [67,68,69,70].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive review demonstrating a significant role for aberrant mucin expression levels in the biological behaviour of precursor lesions and adenocarcinomas of the lower gastrointestinal tract (GIT; Graphical abstract). Significant alterations of distinct mucins were observed in (pre-)cancer cohorts. The most striking observations in the precursor lesions of CRC were the increased expression levels of MUC2 and MUC5AC [12,13,14,15,16, 22, 23]. Furthermore, MUC5AC hypomethylation seems to be specific for serrated polyps harbouring oncogenic mutations, highlighting that such genetic modifications may serve as biomarker to identify serrated pathway-related neoplastic precursors [17]. Contrarily, MUC1 expression was more pronounced in adenomatous polyps, and its expression level positively correlated with the grade of dysplasia and the progression towards adenocarcinoma (Graphical abstract) [12, 24, 25]. The opposite was however seen for MUC2 where a low-level expression was demonstrated in adenomas with increasing dysplasia grade (Graphical abstract) [12, 24, 25]. This difference in altered MUC2 expression, i.e., high-level expression in serrated polyps and low-level expression in adenomas with high-grade dysplasia, was also further shown in CRC adenocarcinomas with distinct pathological features [26, 42]. More specifically, tumours with increased MUC2 expression were associated with mucinous and MSI subtypes and tend to arise in the proximal colon, whereas tumours with low MUC2 expression typically originate from the left-sided colon and rectum (Graphical abstract) [26, 28, 33,34,35, 39, 42]. Furthermore, discrepancies in overall survival have also been reported in relation to high- or low-level MUC2 (Graphical abstract), indicating that this glycoprotein is in fact not acting alone in the carcinogenesis process but cooperates with other mucins of the mucus barrier, as highlighted before [7]. Indeed, altered MUC2 expression in association with increased expression of MUC5AC and MUC6 has been observed in mucinous CRC adenocarcinomas of the proximal colon [34, 39,40,41]. The abundant presence of MUC5AC and MUC6 has been linked to a more favourable prognosis in most studies [34, 43, 47], suggesting that the tumour’s behaviour and molecular characteristics may be influenced by its colonic location (Fig. 4). As right-sided tumours are more frequently associated with poor outcomes [71], it remains to be further investigated whether such tumours simultaneously express MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6, and whether they originate from the serrated or conventional adenoma pathway. Notably, since MUC2 and ectopic MUC5AC expression are more frequently observed in serrated polyps and mucinous adenocarcinomas, this suggests that the simultaneous activation of differentiation pathways of goblet cells and gastric foveolar cells may contribute to the pathogenesis of these lesions. In addition, similar signatures for MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6 have also been described in small intestinal adenocarcinomas [52, 60,61,62], although high MUC5AC expression was associated with poor prognosis (Fig. 4). This finding reinforces the notion that tumour location matters, as it affects tumour behaviour and suggests that the mechanisms driving carcinogenesis may vary depending on the anatomical location within the intestinal tract. Besides alterations in secreted mucin expression, changes in transmembrane mucin expression have also been observed in both mucinous and non-mucinous colorectal cancer subtypes and linked to disease outcome as well (Fig. 4). In particular, increased cytoplasmic expression of MUC1 and MUC13 in tumour cells has been correlated with poorer survival [21, 28, 30, 35, 51], further underscoring their key role in the pathogenesis and progression of colorectal cancer as well as their potential as therapeutic targets and prognostic biomarkers, as described before [7].

This systematic review had some limitations. First, methodological heterogeneity to assess mucin expression resulted in discrepancies. Another limitation was the lack of healthy tissue as a comparison in some studies when investigating mucin expression in benign and malignant lesions. Thirdly, this review is also subject to clinical variability as different clinicopathological features (like 3-year/5-year overall, cancer-specific or progression-free survival) and patient characteristics (particularly geographical distribution) have been investigated among the included studies. Furthermore, heterogeneity in the reporting of survival outcomes (i.e., univariate versus multivariate analyses), the limited range of mucin types investigated, distinct clinical parameters assessed and tumor heterogeneity (mucinous versus non-mucinous tumors), introduced bias into the meta-analyses and resulted in a limited number of eligible studies.

Nevertheless, aberrant mucin signatures reflect distinct molecular pathways in benign and malignant lesions of the lower GIT (Graphical abstract). Furthermore, understanding the differential expression and functional impact of combined secreted and transmembrane mucin signatures may contribute to the refinement of molecular subtyping and the development of prognostic biomarkers for patient stratification and targeted therapeutic strategies in CRC. Besides, mucins are highly polymorphic, and the presence of genetic differences can alter gene expression, resulting in several mRNA isoforms via alternative splicing. While most isoforms encode similar biological functions, some alter protein function, resulting in progression toward disease [7]. Therefore, integrating mucin (isoform)-based markers into diagnostic and molecular stratification frameworks may improve personalized treatment strategies and guide clinical decision-making in intestinal-type cancer management.

References

Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72:338–44.

Dornblaser D, Young S, Shaukat A. Colon polyps: updates in classification and management. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2024;40:14–20.

Joanito I, Wirapati P, Zhao N, Nawaz Z, Yeo G, Lee F, et al. Single-cell and bulk transcriptome sequencing identifies two epithelial tumor cell states and refines the consensus molecular classification of colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2022;54:963–75.

Lan YT, Chang SC, Lin PC, Lin CC, Lin HH, Huang SC, et al. Clinicopathological and Molecular Features of Colorectal Cancer Patients With Mucinous and Non-Mucinous Adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:620146.

Yamashita K, Oka S, Yamada T, Mitsui K, Yamamoto H, Takahashi K, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of primary small bowel adenocarcinoma: a large multicenter analysis of the JSCCR database in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2024;59:376–88.

Kufe DW. Mucins in cancer: function, prognosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:874–85.

Breugelmans T, Oosterlinck B, Arras W, Ceuleers H, De Man J, Hold GL, et al. The role of mucins in gastrointestinal barrier function during health and disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:455–71.

Cantero-Recasens G, Alonso-Marañón J, Lobo-Jarne T, Garrido M, Iglesias M, Espinosa L, et al. Reversing chemorefraction in colorectal cancer cells by controlling mucin secretion. eLife. 2022;11:e73926.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n71.

Gierisch JMBC, Shapiro A, et al. Health Disparities in Quality Indicators of Healthcare Among Adults with Mental Illness: APPENDIX B, NEWCASTLE-OTTAWA SCALE CODING MANUAL FOR COHORT STUDIES. In. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2014.

Liu N, Zhou Y, Lee JJ. IPDfromKM: reconstruct individual patient data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:111.

Krishn SR, Kaur S, Smith LM, Johansson SL, Jain M, Patel A, et al. Mucins and associated glycan signatures in colon adenoma-carcinoma sequence: Prospective pathological implication(s) for early diagnosis of colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016;374:304–14.

Khaidakov M, Lai KK, Roudachevski D, Sargsyan J, Goyne HE, Pai RK, et al. Gastric Proteins MUC5AC and TFF1 as Potential Diagnostic Markers of Colonic Sessile Serrated Adenomas/Polyps. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146:530–7.

Mochizuka A, Uehara T, Nakamura T, Kobayashi Y, Ota H. Hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated ‘adenomas’ of the colon and rectum display gastric pyloric differentiation. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;128:445–55.

Higuchi T, Sugihara K, Jass JR. Demographic and pathological characteristics of serrated polyps of colorectum. Histopathology. 2005;47:32–40.

Hiromoto T, Murakami T, Akazawa Y, Sasahara N, Saito T, Sakamoto N, et al. Immunohistochemical and genetic characteristics of a colorectal mucin-rich variant of traditional serrated adenoma. Histopathology. 2018;73:444–53.

Renaud F, Mariette C, Vincent A, Wacrenier A, Maunoury V, Leclerc J, et al. The serrated neoplasia pathway of colorectal tumors: Identification of MUC5AC hypomethylation as an early marker of polyps with malignant potential. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:1472–81.

Molaei M, Mansoori BK, Mashayekhi R, Vahedi M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Fatemi SR, et al. Mucins in neoplastic spectrum of colorectal polyps: can they provide predictions?. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:537.

Bartley AN, Thompson PA, Buckmeier JA, Kepler CY, Hsu CH, Snyder MS, et al. Expression of gastric pyloric mucin, MUC6, in colorectal serrated polyps. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:169–76.

Owens SR, Chiosea SI, Kuan SF. Selective expression of gastric mucin MUC6 in colonic sessile serrated adenoma but not in hyperplastic polyp aids in morphological diagnosis of serrated polyps. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:660–9.

Walsh MD, Young JP, Leggett BA, Williams SH, Jass JR, McGuckin MA. The MUC13 cell surface mucin is highly expressed by human colorectal carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:883–92.

Cansiz Ersöz C, Kiremitci S, Savas B, Ensari A. Differential diagnosis of traditional serrated adenomas and tubulovillous adenomas: a compartmental morphologic and immunohistochemical analysis. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2020;83:549–56.

Myerscough N, Sylvester PA, Warren BF, Biddolph S, Durdey P, Thomas MG, et al. Abnormal subcellular distribution of mature MUC2 and de novo MUC5AC mucins in adenomas of the rectum: immunohistochemical detection using non-VNTR antibodies to MUC2 and MUC5AC peptide. Glycoconj J. 2001;18:907–14.

Li A, Goto M, Horinouchi M, Tanaka S, Imai K, Kim YS, et al. Expression of MUC1 and MUC2 mucins and relationship with cell proliferative activity in human colorectal neoplasia. Pathol Int. 2001;51:853–60.

Baldus SE, Hanisch FG, Pütz C, Flucke U, Mönig SP, Schneider PM, et al. Immunoreactivity of Lewis blood group and mucin peptide core antigens: correlations with grade of dysplasia and malignant transformation in the colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Histol Histopathol. 2002;17:191–8.

Park SY, Lee HS, Choe G, Chung JH, Kim WH. Clinicopathological characteristics, microsatellite instability, and expression of mucin core proteins and p53 in colorectal mucinous adenocarcinomas in relation to location. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:40–47.

Kim DH, Kim JW, Cho JH, Baek SH, Kakar S, Kim GE, et al. Expression of mucin core proteins, trefoil factors, APC and p21 in subsets of colorectal polyps and cancers suggests a distinct pathway of pathogenesis of mucinous carcinoma of the colorectum. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:957–64.

Renaud F, Vincent A, Mariette C, Crépin M, Stechly L, Truant S, et al. MUC5AC hypomethylation is a predictor of microsatellite instability independently of clinical factors associated with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2811–21.

Losi L, Scarselli A, Benatti P, Ponz de Leon M, Roncucci L, Pedroni M, et al. Relationship between MUC5AC and altered expression of MLH1 protein in mucinous and non-mucinous colorectal carcinomas. Pathol Res Pr. 2004;200:371–7.

You JF, Hsieh LL, Changchien CR, Chen JS, Chen JR, Chiang JM, et al. Inverse effects of mucin on survival of matched hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer and sporadic colorectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4244–50.

Al-Maghrabi J, Sultana S, Gomaa W. Low expression of MUC2 is associated with longer disease-free survival in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:61–66.

Lugli A, Zlobec I, Baker K, Minoo P, Tornillo L, Terracciano L, et al. Prognostic significance of mucins in colorectal cancer with different DNA mismatch-repair status. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:534–9.

Nishida T, Egashira Y, Akutagawa H, Fujii M, Uchiyama K, Shibayama Y, et al. Predictors of lymph node metastasis in T1 colorectal carcinoma: an immunophenotypic analysis of 265 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:905–15.

Betge J, Schneider NI, Harbaum L, Pollheimer MJ, Lindtner RA, Kornprat P, et al. MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 in colorectal cancer: expression profiles and clinical significance. Virchows Arch. 2016;469:255–65.

Walsh MD, Clendenning M, Williamson E, Pearson SA, Walters RJ, Nagler B, et al. Expression of MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B, and MUC6 mucins in colorectal cancers and their association with the CpG island methylator phenotype. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1642–56.

Yao T, Tsutsumi S, Akaiwa Y, Takata M, Nishiyama K, Kabashima A, et al. Phenotypic expression of colorectal adenocarcinomas with reference to tumor development and biological behavior. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2001;92:755–61.

El-Sayed IH, Lotfy M, Moawad M. Immunodiagnostic potential of mucin (MUC2) and Thomsen-Friedenreich (TF) antigens in Egyptian patients with colorectal cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharm Sci. 2011;15:91–97.

Yao T, Takata M, Tustsumi S, Nishiyama K, Taguchi K, Nagai E, et al. Phenotypic expression of gastrointestinal differentiation markers in colorectal adenocarcinomas with liver metastasis. Pathology. 2002;34:556–60.

Elzagheid A, Emaetig F, Buhmeida A, Laato M, El-Faitori O, Syrjänen K, et al. Loss of MUC2 expression predicts disease recurrence and poor outcome in colorectal carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:621–8.

Hirano K, Nimura S, Mizoguchi M, Hamada Y, Yamashita Y, Iwasaki H. Early colorectal carcinomas: CD10 expression, mucin phenotype and submucosal invasion. Pathol Int. 2012;62:600–11.

Kang H, Min BS, Lee KY, Kim NK, Kim SN, Choi J, et al. Loss of E-cadherin and MUC2 expressions correlated with poor survival in patients with stages II and III colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:711–9.

Perez RO, Bresciani BH, Bresciani C, Proscurshim I, Kiss D, Gama-Rodrigues J, et al. Mucinous colorectal adenocarcinoma: influence of mucin expression (Muc1, 2 and 5) on clinico-pathological features and prognosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:757–65.

Hazgui M, Weslati M, Boughriba R, Ounissi D, Bacha D, Bouraoui S. MUC1 and MUC5AC implication in Tunisian colorectal cancer patients. Turk J Med Sci. 2021;51:309–18.

Sylvester PA, Myerscough N, Warren BF, Carlstedt I, Corfield AP, Durdey P, et al. Differential expression of the chromosome 11 mucin genes in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2001;195:327–35.

Rico SD, Höflmayer D, Büscheck F, Dum D, Luebke AM, Kluth M, et al. Elevated MUC5AC expression is associated with mismatch repair deficiency and proximal tumor location but not with cancer progression in colon cancer. Med Mol Morphol. 2021;54:156–65.

Katano T, Mizoshita T, Tsukamoto H, Nishie H, Inagaki Y, Hayashi N, et al. Ectopic Gastric and Intestinal Phenotypes, Neuroendocrine Cell Differentiation, and SOX2 Expression Correlated With Early Tumor Progression in Colorectal Laterally Spreading Tumors. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16:141–6.

Kocer B, Soran A, Erdogan S, Karabeyoglu M, Yildirim O, Eroglu A, et al. Expression of MUC5AC in colorectal carcinoma and relationship with prognosis. Pathol Int. 2002;52:470–7.

Zhang W, Tang W, Inagaki Y, Qiu M, Xu HL, Li X, et al. Positive KL-6 mucin expression combined with decreased membranous beta-catenin expression indicates worse prognosis in colorectal carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2008;20:1013–9.

Kesari MV, Gaopande VL, Joshi AR, Babanagare SV, Gogate BP, Khadilkar AV. Immunohistochemical study of MUC1, MUC2 and MUC5AC in colorectal carcinoma and review of literature. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34:63–67.

Suzuki H, Shoda J, Kawamoto T, Shinozaki E, Miyahara N, Hotta S, et al. Expression of MUC1 recognized by monoclonal antibody MY.1E12 is a useful biomarker for tumor aggressiveness of advanced colon carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21:321–9.

Baldus SE, Mönig SP, Hanisch FG, Zirbes TK, Flucke U, Oelert S, et al. Comparative evaluation of the prognostic value of MUC1, MUC2, sialyl-Lewis(a) and sialyl-Lewis(x) antigens in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Histopathology. 2002;40:440–9.

Zhang MQ, Lin F, Hui P, Chen ZM, Ritter JH, Wang HL. Expression of mucins, SIMA, villin, and CDX2 in small-intestinal adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:808–16.

Guo Q, Tang W, Inagaki Y, Midorikawa Y, Kokudo N, Sugawara Y, et al. Clinical significance of subcellular localization of KL-6 mucin in primary colorectal adenocarcinoma and metastatic tissues. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:54–59.

Tozawa E, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Nishikura K, Mukai G, Suda T, et al. Mucin expression, p53 overexpression, and peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration of advanced colorectal carcinoma with mucus component: Is mucinous carcinoma a distinct histological entity?. Pathol Res Pr. 2007;203:567–74.

Baldus SE, Mönig SP, Huxel S, Landsberg S, Hanisch FG, Engelmann K, et al. MUC1 and nuclear beta-catenin are coexpressed at the invasion front of colorectal carcinomas and are both correlated with tumor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2790–6.

Duncan TJ, Watson NFS, Al-Attar AH, Scholefield JH, Durrant LG. The role of MUC1 and MUC3 in the biology and prognosis of colorectal cancer. World J Surgical Oncol. 2007;5:31.

Matsuyama T, Ishikawa T, Mogushi K, Yoshida T, Iida S, Uetake H, et al. MUC12 mRNA expression is an independent marker of prognosis in stage II and stage III colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2292–9.

Oh HR, An CH, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Frameshift mutations of MUC15 gene in gastric and its regional heterogeneity in gastric and colorectal cancers. Pathol Oncol Res. 2015;21:713–8.

Xiao X, Wang L, Wei P, Chi Y, Li D, Wang Q, et al. Role of MUC20 overexpression as a predictor of recurrence and poor outcome in colorectal cancer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:151.

Shibahara H, Higashi M, Koriyama C, Yokoyama S, Kitazono I, Kurumiya Y, et al. Pathobiological implications of mucin (MUC) expression in the outcome of small bowel cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86111.

Jun SY, Eom DW, Park H, Bae YK, Jang KT, Yu E, et al. Prognostic significance of CDX2 and mucin expression in small intestinal adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:1364–74.

Kumagai R, Kohashi K, Takahashi S, Yamamoto H, Hirahashi M, Taguchi K, et al. Mucinous phenotype and CD10 expression of primary adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2700–10.

Ishikawa R, Yamada H, Saitsu H, Miyazaki R, Takahashi J, Takinami R, et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular evolutionary features of jejunoileal adenocarcinoma unveiled through comparative analysis with colorectal adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia. 2025;66:101180.

Terada T. An immunohistochemical study of primary signet-ring cell carcinoma of the stomach and colorectum: II. Expression of MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 in normal mucosa and in 42 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:613–21.

Winn B, Tavares R, Fanion J, Noble L, Gao J, Sabo E, et al. Differentiating the undifferentiated: immunohistochemical profile of medullary carcinoma of the colon with an emphasis on intestinal differentiation. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:398–404.

Kurosawa T, Murakami T, Yamashiro Y, Terukina H, Hayashi T, Saito T, et al. Mucin phenotypes and clinicopathological features of colorectal adenocarcinomas: Correlation with colorectal adenocarcinoma with enteroblastic differentiation. Pathol Res Pr. 2022;232:153840.

Chang MS, Byeon SJ, Yoon SO, Kim BH, Lee HS, Kang GH, et al. Leptin, MUC2 and mTOR in appendiceal mucinous neoplasms. Pathobiology. 2012;79:45–53.

Yoon SO, Kim BH, Lee HS, Kang GH, Kim WH, Kim YA, et al. Differential protein immunoexpression profiles in appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: a special reference to classification and predictive factors. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:1102–12.

Yajima N, Wada R, Yamagishi S, Mizukami H, Itabashi C, Yagihashi S. Immunohistochemical expressions of cytokeratins, mucin core proteins, p53, and neuroendocrine cell markers in epithelial neoplasm of appendix. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:1217–25.

Elsayed B, Elshoeibi AM, Elhadary M, Al-Jubouri AM, Al-Qahtani N, Vranic S, et al. Molecular and immunohistochemical markers in appendiceal mucinous neoplasms: A systematic review and comparative analysis with ovarian mucinous neoplasms and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Histol Histopathol. 2025;40:621–33.

Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Wilkins S, Plazzer JP, Yap R, McMurrick PJ. Prognostic factors and survival disparities in right-sided versus left-sided colon cancer. Scientific Rep. 2024;14:12306.

Acknowledgements

We thank Miel Peeters for the technical support in data analysis.

Funding

AS, BYDW, and TV are supported by the internal university fund of the Antwerp University (BOF-IMPULS number: FFB240455). BO is supported by the Antwerp University Valorisation funds (IOF-POC number: FFI230207). TV is holder of Senior Clinical Investigator grant 1803723 N of the Research Foundation - Flanders (Belgium) (FWO).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AVM, JG, and AS conceived and designed the study. AS supervised the study. AVM and JG wrote the first draft of the manuscript, analysed the raw data, interpreted the obtained results, and designed the graphs. BO, TVD, JDM, and BYDW provided intellectual support in the study design. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AS and BYDW are inventors of patent applications related to mucin isoforms in diseases characterized by barrier dysfunction, including GI cancers (WO/2021/013479; WO2025/120137). All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Meer, A., Gilis, J., Oosterlinck, B. et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of mucin signatures in lower gastrointestinal cancer–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 134, 367–376 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03297-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-025-03297-7