Abstract

Crosslinked rubbers and gels derive their softness and toughness from a three-dimensional network of junction points connected by polymer strands. Classical affine and phantom network models qualitatively relate the network architecture to the shear modulus but fail to predict absolute values owing to elastically ineffective defects such as loops and dangling chains. In the present study, we employed coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations combined with an iterative defect-removal algorithm to compare four model networks formed under various cross-linking protocols and binding ratios: three-/four-armed star polymer networks (SPNs) and three-/four-armed telechelic polymer networks (TPNs). We directly counted elastically effective junctions and eliminated primitive and even higher-order defects. The SPNs exhibited higher shear moduli than the TPNs did, which was a consequence of more rapid generation and greater density of effective junctions as well as suppressed loop formation. Remarkably, in both network types, the simulated modulus G obeyed:

where Gph represents the prediction by the phantom network model using the actual effective junction, which is independent of the cross-linking protocols, binding ratio, or functionality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cross‑linked rubbers and gels are soft materials that are widely used in structural applications that require both softness and toughness, such as tires and isolators for buildings. The distinctive mechanical behavior of these materials is attributed to a polymer network that is composed of junction points connected by network strands. Many theoretical models have been developed for rubbers [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] and gels [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] to determine the relationship between this network architecture and their bulk properties. The affine [1, 2] and phantom [3,4,5,6] network models are two of the most widely used classical models.

In both frameworks, junction points are assumed to deform affinely with macroscopic strain, and the elastic forces of the network originate from the loss of conformational entropy of the strands. Moreover, all strands are assumed to deform uniformly, irrespective of their length. The affine network model predicts the following:

whereas the phantom network model yields:

where ν represents the number density of strands, μ denotes the number density of junctions, and kBT indicates the thermal energy at temperature T. Although these models qualitatively capture trends, such as the increase in the shear modulus with cross-link density, they do not quantitatively provide accurate values.

The root of this discrepancy is elastically ineffective structures (e.g., dangling chains and loops) and more complex defects (e.g., superloops and superbridges) [26, 27], which do not contribute to elasticity but nonetheless affect the apparent junction and strand density. To increase model accuracy, researchers have designed model networks that minimize these defects, typically by using a uniform strand length [28]. Common examples include telechelic polymer networks (TPNs), which are composed of linear chains and a multifunctional telechelic cross-linker, e.g., polydimethylsiloxane [29] (PDMS; hereafter, we refer to these networks as TPNs with reference to the literature [28]), and star polymer networks, which are composed of multiple terfunctional macromers, e.g., tetra‑ or tri‑polyethylene glycol (PEG) gels [30, 31] (hereafter, we refer to these networks as SPNs with reference to the literature [28]).

The Scanlan–Case criterion[11, 12], i.e., a junction that is connected to the percolated network via at least three independent paths, is widely used to define an elastically effective structure. In practice, the mean-field approximation of Miller and Macosko [13] is used to estimate the number of these junctions. The resulting Miller–Macosko model accurately predicts the effectiveness of the junctions, as confirmed by mechanical tests [18,19,20, 32, 33] and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structural analyses [34]. Coarse‑grained molecular dynamics simulations by Gusev and Schwarz further validated this theory, reporting that it reliably predicts the plateau moduli of end cross-linking PDMS, despite the omission of explicit percolation mechanisms [35].

Unfortunately, experiments were unable to determine the absolute numbers of primitive defects (e.g., loops and dangling ends) until direct molecular simulations enabled their enumeration [36,37,38,39]. Among these studies, Furuya and Koga conducted comprehensive investigations into the cross-linking structures of SPNs and TPNs, focusing on the effects of polymer chain length and initial concentration during the cross-linking process. The authors examined fully cross-linked SPNs and TPNs over a range of initial polymer concentrations and evaluated their mechanical properties under various swelling conditions. Their findings revealed that SPNs have higher densities of effective strands—and consequently higher shear moduli—than TPNs do [39]. In their analysis, junctions with three or more connected strands were considered “elastically effective”. However, their work was limited to nearly fully cross-linked networks, and exploring the structure or defect distribution in incompletely cross-linked systems, particularly in the prepercolation regime, was difficult.

To investigate defect structures and the effective network in more inhomogeneous systems that contain large-scale defects, we recently developed an iterative algorithm that identifies and removes all primitive and higher-order defects—including superloops and superdangling chains—by tracing paths to the percolated network. We applied this method to SPNs to show that the Miller–Macosko approximation very precisely predicts the remaining number of effective junctions [40]. We also showed that the shear moduli are approximately twice those predicted by the phantom network model with the detected effective junctions in the case of SPNs.

In the present study, we extended that approach to incompletely cross‑linked networks formed under different protocols. We compared PDMS-like TPNs and tetra‑/tri-PEG gel-like SPNs across various binding ratios and determined how their formation mechanisms affect defect populations and mechanical responses. We discovered that the SPNs inherently reincorporated loops into elastically effective strands, yielding a higher fraction of effective strands, whereas the TPNs tended to trap loops. Consequently, the measured shear moduli were approximately twice those predicted by the phantom network model with an effective network, independent of the cross-linking protocol, binding ratio, or junction functionality.

Methods

Coarse-grained models and system setup

The network was based on the classical Kremer–Grest model [41]. We prepared two TPN systems, each comprising a telechelic polymer and a multifunctional cross-linker, and two SPNs comprising different terfunctional macromers (Fig. 1). We also used two values (3 and 4) to represent the functionality of branch f. The number of beads in the telechelic polymer was 8, and the number of beads in the multifunctional cross-linker was f + 1. The number of beads per arm in the terfunctional macromer was 5. In this way, the resulting structures were designed to have 10 uniform beads per network strand in the ideally cross-linked state, as shown in Fig. 1.

The beads at the ends of the arms were assigned as reactive beads, and the other beads were assigned as normal beads (C). For the SPNs, we prepared two types of macromers with different reactive beads (A and B), as shown in Fig. 1. For the TPNs, the terminal beads of the cross-linker molecules and the telechelic polymers were A and B, respectively. By utilizing the reaction calculation only between beads A and B to form an A–B bond, we obtained the structures of the end-cross-linked elastomer, as shown in Fig. 1.

The nonbonding interaction is expressed by the repulsive Lennard Jones potential, which is known as the Weeks–Chandler–Andersen (WCA) potential below:

We used finitely extensible nonlinear elastic (FENE)–Lennard‒Jones (LJ) potential as a bonding potential (UWCA + UFENE):

where σ and ε0 represent the units of length and energy, respectively, and Rmax denotes the maximum length of the FENE potential. All the simulations were performed on the NVT ensemble (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) using the Langevin equation with a friction constant Γ = 0.5τ−1, where τ represents the unit of time. We also examined the effect of the friction constant Γ on the mechanical properties, as discussed in Section 3.3.

Generation of the cross-linked structure and uniaxial elongation

We generated the cross-linked structures of the 3- and 4-armed systems with the TPN- and SPN-type cross-linking protocols, resulting in a total of four systems. For each system, the same numbers of A- and B-type macromers were randomly placed in the box while keeping the total number of beads in the system approximately 105 under the condition that the number density of beads ρN = 0.85 σ−3 in the isotropic box. The parameters of the four systems are listed in Table 1. Note that we unified the box size and the number of network strands in an ideally cross-linked state (rA–B = 1), thereby ensuring that the moduli should have the same value according to the affine network model.

For each of these four systems, we performed 106τ structural relaxation simulations followed by a reaction calculation. For the reaction conditions, a bond was kinetically fabricated at an acceptance rate of 0.01 between reaction bead A and reaction bead B when they approached the criterion radius rc = 1.3σ of each other, in reference to classical work [42]. The bond formation decision is made at every MD time step with the acceptance rate. Shorter rc values are often used recently; we also examined the effect of this rc value on the cross-linking structures, as shown in Section S1 in the Supporting Information. The binding ratio of the sample was defined as rA–B = 2nA–B/(nA + nB + 2nA–B), where nA–B, nA, and nB were the numbers of A–B bonds, unbonded A beads and unbonded B beads in the system, respectively. Reaction times greater than 104 τ were used for the reaction calculation, enabling the binding ratios at all the final states rA–B, final to ultimately exceed 0.96, as shown in Table 1.

We performed mechanical and structural analyses on the structures formed during the reaction procedure. We selected target binding ratios of rA–B,target = 0.25, 0.40, 0.55, 0.70, 0.85, 0.95, and the final state and recorded the structure at the time when rA–B exceeded the target binding ratio rA–B,target for the uniaxial elongation calculations. The resulting binding ratios rA–B are summarized in Table 2. The recorded structures were then equilibrated for 105 τ at 1T0 as the 2nd structural relaxation.

Uniaxial elongation simulations along the z-axis were performed for the resulting 28 structures at a speed of 1.0 × 10−6 τ. The maximum elongation ratio was 1.4. We analyzed the obtained snapshots to obtain the stress–extension ratio curves by defining the stress tensor \({{{\boldsymbol{\sigma }}}}\) on the basis of the virial:

where V represents the volume of the cell, \(\dot{{{{{\boldsymbol{r}}}}}_{{{{\boldsymbol{n}}}}}}\) denotes the velocity of the nth bead, rnm indicates the position of the nth bead relative to the mth bead, and Fnm represents the force on the nth bead generated from the potential of the mth bead. We then calculate the engineering stress σeng using the diagonal components \({\sigma }_{{xx}},{\sigma }_{{yy}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{zz}}\):

The equilibrium and elongation simulations were performed using LAMMPS [43], and the reaction simulations were conducted using COGNAC101 on OCTA 84 [44].

Structural analysis

We used our proposed methods [40], which are based on the Scanlan–Case criteria, for extraction of the elastically effective network from the cross-linked network. In our algorithm [40], the effective junctions and strands are extracted by recursively eliminating the elastically ineffective junctions from the original network. The ineffective junctions can be considered the following four network defects (Fig. 2a–d):

-

1.

Sols: the junctions not connected to the effective network.

-

2.

Dangling fronts: the junctions connected to the effective network by one path.

-

3.

Bridge centers: the junctions connected to the effective network by two paths.

-

4.

Ineffective loops: paths connected to the same junction.

We used iterative algorithms to self-consistently eliminate higher-order defects, i.e., superdanglings, superloops, and superbridges (Fig. 2e–g). Consequently, no such defects were detected. The practical analysis process is summarized in our previous paper [40] and briefly presented in Section S2 in the Supporting Information. Some examples of the procedures for the bridge center and dangling end are shown in Section S3 in the Supporting Information. With these procedures, the superloops and superdangling chains are also eliminated. The detected numbers of dangling ends (f = 1), bridge centers (f = 2), and n-armed effective chains (f > 3) are represented by Nbridge, Ndangling, and Neffective,f, respectively. The number of sols (f = 0) is calculated by subtraction of Nbridge, Ndangling, and Neffective from the total number of junctions, i.e., the number of macromers or the number of multifunctional CLs in Table 1.

Results and discussion

Mechanical properties

Each stress–elongation ratio curve obtained in the simulations is shown in Fig. 3. For all the systems, the stress increases as the binding ratio increases. This is natural behavior considering classical rubber elasticity theories. The binding ratio rA–B has a criterion for stress emergence and should determine the percolation point. Because all curves can be fitted with Neo-Hookean curves, the elastic moduli Gsim were evaluated using the following equation:

We also took the Mooney‒Rivlin plots in Section S4 (Fig. S8) in the Supporting Information and confirmed that the curves clearly show a plateau corresponding to the modulus G obtained by Neo-Hookean fitting. The resulting G values are summarized and plotted against rA–B in Fig. 4. We also show the predicted percolation points rA–Bgel as arrows using the theoretical Miller–Macosko model in the same figure as the arrows. Our analysis confirmed that the elastic modulus emerged just after the predicted percolation point in all the systems. Therefore, the Miller–Macosko approximation is reasonable and validates our own work [40] and that of Gusev and Schwarz [35]. The elastic moduli of the TPN systems were lower than those of the SPN systems for both numbers of arms, whereas the network strand density in an ideally cross-linked state was the same. This finding reveals that the SPN mechanism makes elastically effective strands more efficiently than the TPN mechanism does, as suggested by the work of Furuya and Koga [39].

Shear moduli obtained from uniaxial elongation plotted against the binding ratio rA–B. The arrows indicate theoretical predictions of the percolation point rA–Bgel included in Table 3 and the Appendix

Structural analysis

To determine the correlation between this elasticity and the cross-linking structure, especially under cross-linking procedures, we performed a structural analysis using graph theory-based effective network analysis, as described in the Methods section. We plotted Nsol, Ndangling, Nbridge, Neffective,3, and Neffective,4 against the binding ratio, as shown in Fig. 5a–d. All the systems exhibited a similar tendency with respect to Ndangling and Nbridge. First, the number of dangling fronts increased, and then, the dangling fronts saturate (step I), and the bridge center (step II) increases. Second, the effective junctions emerged, and the number of dangling fronts and bridge centers simultaneously decreased (step III). The general mechanism is that shown in our literature [40] (for SPNs) and in Fig. 5e: Region I corresponds to the connection process of multifunctional CLs or macromers to neighboring CLs because only Ndangling increases. Region II corresponds to the elongation process of long superdangling chains because Ndangling remains constant, but Nbridge increases.

Number of elastically ineffective/effective junctions in the a TPN 3-arm, b TPN 4-arm, c SPN 3-arm, and d SPN 4-arm. e Suggested general percolation mechanism for the TPN and SPN. The arrows indicate the theoretical prediction of the percolation points rA–Bgel included in Table 3 and the Appendix. (TPN represents the telechelic polymer network; SPN represents the star polymer network)

The delay of the transition from I to II and from II to III in TPNs should correspond to the delay in the percolation points. According to the discussion of the Miller–Macosko model and Appendix in the present paper, the probability of the connection of two junctions in the TPN system is represented as rA–B2, whereas that in the SPN system is represented as rA–B. Therefore, more A/B reactions are needed to form a network with the same number of network strands by the TPN mechanism than by the SPN mechanism.

We also obtained the number of effective strands and the number of elastically ineffective loops in the networks Nloop from the structural analysis. The total number of effective strands is plotted against rA–B in Fig. 6a. The curves reveal behavior that is similar to that shown in Fig. 4, which was produced by mechanical analysis. Furthermore, the effective chains emerged immediately after the percolation points, which was the same behavior as the G values. This finding confirms that the occurrence of effective junctions and percolation were synchronized and clearly indicates that there were fewer effective strands in the TPNs than in the SPNs.

a Number of detected effective strands plotted against rA–B, b number of ineffective loops plotted against rA–B, and c suggested mechanism for the formation and transformation of ineffective loops. The arrows indicate the theoretically predicted percolation points rA–Bgel included in Table 3 and the Appendix. (TPN represents the telechelic polymer network; SPN represents the star polymer network)

We also counted the number of ineffective loops eliminated in the graph transformation process (Section 2.3). The number of detected loops is plotted against rA–B, as shown in Fig. 6b. The TPNs clearly had more ineffective loops. The number of loops in the SPNs decreased immediately after the percolation point, as indicated by the arrows, which is the same behavior as Ndangling and Nbridge. However, the number of ineffective loops in the TPNs simply increased and never decreased. Consequently, we consider that SPNs reduce the number of ineffective loops to several effective strands by the proceeding reaction, whereas TPNs do not have this mechanism when the smallest loops are fabricated (Fig. 6c). Therefore, it is obvious that SPNs should have fewer ineffective loops and consequently have more effective strands and higher moduli.

Quantitative evaluation of the classical model

For a quantitative evaluation, we compared the elastic modulus G obtained by uniaxial elongation calculation with the predicted values Gaf obtained from the affine network model and Gph obtained from the phantom network model calculated from the structural analysis.

Affine network model:

Phantom network model:

where f represents the effective functionality of the junction; ξ denotes the cycle rank, the number density of closed cycles in the network; ν indicates the network strand density, and μf represents the junction density with functionality of f. In the 3-armed system, f is uniformly equal to 3. For the 4-armed system, the effective branching number varies during the crosslinking procedure, as shown in Fig. 5b, d.

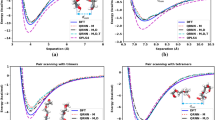

A comparison with the Gaf values revealed that there was no linear dependence between G and Gaf in the case of 4 arms in either the SPNs or the TPNs as illustrated in Fig. 7a. However, a comparison with the Gph values (Fig. 7b) revealed that the values of both the SPNs and TPNs exhibited a proportional relationship with the same proportional constant, independent of the number of arms (G ≈ 2Gph). This equation was confirmed only for SPNs in previous work [40]. However, the present work confirms that the elastic modulus is approximately twice that predicted by the phantom network model with the Scanlan–Case criterion, regardless of the number of branches or cross-linking protocols. This proportionality between G analyzed by mechanical tests and Gph predicted by the phantom network model with an effective network was also confirmed experimentally by Sakumichi et al. (G ≈ 2.4Gph) using the Miller‒Macosko approximation for structural prediction [25], confirming the approximate twofold discrepancy between the theoretical predictions and the experimental observations of elastic moduli.

Several possible explanations are considered for this factor of 2 discrepancy, including nonlinear spring behavior, excluded volume effects, Brownian forces, and flaws such as the double counting of closed circuits. To investigate this issue further, we conducted additional elongation simulations starting from the final binding states, systematically varying parameters such as the binding potential, excluded volume interaction (Eq. 1), and the friction constant Γ in the Langevin equation.

For the friction constant in Langevin dynamics, we tested values of Γ = 1.0 and 2.0 [τ-1]. To evaluate the effect of the excluded volume, we turned off the nonbonding potential (virtual chain). For the bonding potential, we replaced the FENE-LJ potential with a harmonic potential defined by

with K = 1000 [ε/σ2] and equilibrium bond length r0 = 1.0 σ.

The results shown in Fig. 8 indicate that the friction constant has a minimal effect on the stress‒elongation ratio curve. Furthermore, the virtual chain exhibits slightly higher moduli than the real chain does, which can be attributed to variations in the relative extension rate of network strands compared with free chains. The harmonic spring slightly reduced elasticity, but not nearly enough to account for the twofold discrepancy between the theoretical prediction and experimental observation of the elastic modulus. Overall, these parameters had minimal impacts on the uniaxial elongation curves. Additionally, stress evaluations via energy-minimized networks, such as those performed by Svaneborg et al. [45], Nishi et al. [19, 20], and Masubuchi et al. [46], may provide further insights, which we will investigate in future studies.

Stress‒elongation ratio curves of the Γ = 1.0 and 2.0 [τ-1] chains, chains without excluded volumes (virtual chains), and virtual chains with a harmonic bonding potential at the final binding states for the a TPN 3-arm, b TPN 4-arm, c SPN 3-arm, and d SPN 4-arm (TPN represent the telechelic polymer network; SPN represent the star polymer network)

We also performed additional structural analyses on SPNs to recalculate the theoretical Gph by removing not only the three primitive defects (Fig. 2b–d) but also multiple binding strands, as described in Section S5 in the Supporting Information. Nevertheless, the relation G ≈ 2Gph held, suggesting that the effect of multiple binding events is negligible. Notably, Masubuchi et al. reported a proportionality factor of approximately 0.3 between the elastic modulus G and the phantom network model prediction with the Miller‒Macosko approximation in simulations of energy-minimized networks without conformational fluctuations [46]. However, their simulations were conducted at much higher polymer densities (ρ = 2‒16) than our conditions (ρ = 0.85), and the force field used during cross-linking (virtual chain model) is different from that used in our work (Kremer‒Grest model). This finding suggests that the proportionality factor can be sensitive to these factors, as well as to the conformational fluctuations of the network strands.

In the virtual chain model employed by Masubuchi et al., when the reaction progresses and the clusters become larger, the clusters may collapse excessively. As a result, neighboring clusters are weakly connected after cluster formation, resembling network formation in poor solvents. Therefore, the proportionality factor between G and Gph may rely on the polymer concentration and the choice of the force field during cross-linking, as well as these conditions used during mechanical analysis. A systematic investigation of these dependencies, including reaction kinetics and network architecture, remains an important topic for future studies.

Overall, the molecular origin of Factor 2 remains unknown. We now hypothesize that the conformation entropy of the closed cycles (effective loops) should also be considered because the Gph values are proportional to the number density of the closed cycles in the network (cycle rank). Calculations and analyses to verify this hypothesis will be conducted and reported in future works.

Conclusions

In the present study, we used coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the relationships among cross-linking mechanisms, cross-linking structures, and mechanical properties, especially by focusing on two cross-linking mechanisms: TPNs and SPNs. The results showed that the moduli of SPNs are greater than those of TPNs. A delay occurs in the generation of elastically effective junctions and a decrease in the number of effective junctions in TPNs compared with those in SPNs, which is caused by a decrease in the probability of forming strands between junctions (rA–B to rA–B2) and by an increase in the number of ineffective loops. We consider that these ineffective loops are a consequence of the absence of a mechanism by which they are transformed into several effective strands, as shown in Fig. 6c. We also confirmed that the elastic modulus can be predicted (G = 2Gph) by the phantom network model with respect to the number of effective junctions, regardless of the cross-linking protocols, binding rate, or number of branches. These findings will provide fresh insights into classical rubber-elasticity theory and elucidate how cross-linking protocols control network structure—particularly loop formation—and thereby determine mechanical properties.

Appendix

Theoretical expression of the percolation points of SPNs and TPNs using the Miller–Macosko model.

The Miller–Macosko model [13] makes the following assumption:

-

1.

The rates of reaction of all the reaction points are the same.

-

2.

No intramolecular reaction occurs.

The authors assumed the rate of reaction A–B to be p, where p had the same value as the binding ratio rA–B in our simulation. The authors also defined the probability that one n-armed terminal (bead A or B) did not belong to the effective network P(F = n), where F represents the total functionality of the macromer or multifunctional CL. In the case of the SPN, P(F = n) is expressed as:

The first term assumes that the terminal bead (“A” in Fig. 9a) does not belong to the effective network if the A–B bond is not formed, as shown in Fig. 9aI. The second term assumes that the terminal bead does not belong to the effective network and that the rest of the terminals of the opponent macromer are not connected to the effective network, each of which has a probability of P(F = 4), as shown in Fig. 9aII. For the 3-armed system (F = 3), the probability P(F = 3) can be expressed as:

With p = rA–B, P(F = 3) and P(F = 4) can then be expressed as follows:

In the case of the TPN, p is replaced by p2 because two multifunctional CLs are connected only when two A–B reactions occur between a multifunctional CL and a telechelic chain and between the telechelic chain and another multifunctional CL, as shown in Fig. 9b:

This model predicts only postpercolated structures. Therefore, the equivalent domain of definition rA–Bgel < rA–B < 1 can be estimated from the value range condition 0 ≤ P(F = n)≤1 and from Eqs. (10), (11), (14), and (15). The percolation points rA–Bgel are listed in Table 3.

References

Kuhn W. Über die Gestalt fadenförmiger Moleküle in Lösungen. Kolloid-Z. 1934;68:2–15.

Kuhn W. Beziehungen zwischen Molekülgröße, statistischer Molekülgestalt und elastischen Eigenschaften hochpolymerer Stoffe. Kolloid-Z. 1936;76:258–71.

Treloar LRG. The statistical length of long-chain molecules. Trans Faraday Soc. 1946;42:77.

Guth E, James HM. Elastic and thermoelastic properties of rubber like materials. Ind Eng Chem. 1941;33:624–9.

James HM, Guth E. Theory of the Elastic Properties of Rubber. J Chem Phys. 1943;11:455–81.

James HM, Guth E. Theory of the Elasticity of Rubber. J Appl Phys. 1944;15:294–303.

Flory PJ. Statistical thermodynamics of random networks. Proc R Soc Lond A. 1976;351:351–80.

Flory PJ. Molecular theory of rubber elasticity. Polym J. 1985;17:1–12.

Tobolsky AV, Callinan TD. Properties and Structure of Polymers. J Electrochem Soc. 1960;107:243C.

Wang MC, Guth E. Statistical theory of networks of non-Gaussian flexible chains. J Chem Phys. 1952;20:1144–57.

Scanlan J. The effect of network flaws on the elastic properties of vulcanizates. J Polym Sci. 1960;43:501–8.

Case LC. Branching in polymers. I. Network defects. J Polym Sci. 1960;45:397–404.

Miller DR, Macosko CW. A new derivation of post gel properties of network polymers. Macromolecules. 1976;9:206–11.

Langley NR. Elastically effective strand density in polymer networks. Macromolecules. 1968;1:348–52.

Pearson DS. Scattered Intensity from a Chain in a Rubber Network. Macromolecules. 1977;10:696–701.

Ball RC, Doi M, Edwards SF, Warner M. Elasticity of entangled networks. Polymer. 1981;22:1010–8.

Edwards SF. & Vilgis, Th. The effect of entanglements in rubber elasticity. Polymer. 1986;27:483–92.

Akagi Y, Matsunaga T, Shibayama M, Chung U, Sakai T. Evaluation of topological defects in tetra-PEG Gels. Macromolecules. 2010;43:488–93.

Nishi K, Fujii K, Chung U, Shibayama M, Sakai T. Experimental observation of two features unexpected from the classical theories of rubber elasticity. Phys Rev Lett. 2017;119:267801.

Nishi K, Noguchi H, Sakai T, Shibayama M. Rubber elasticity for percolation network consisting of Gaussian chains. J Chem Phys. 2015;143:184905.

Wang R, Alexander-Katz A, Johnson JA, Olsen BD. Universal cyclic topology in polymer networks. Phys Rev Lett. 2016;116:188302.

Zhong M, Wang R, Kawamoto K, Olsen BD, Johnson JA. Quantifying the impact of molecular defects on polymer network elasticity. Science. 2016;353:1264–8.

Gu Y, et al. Semibatch monomer addition as a general method to tune and enhance the mechanics of polymer networks via loop-defect control. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:4875–80.

Yoshikawa Y, Sakumichi N, Chung U, Sakai T. Negative Energy Elasticity in a Rubberlike Gel. Phys Rev X. 2021;11:011045.

Sakumichi N, Yoshikawa Y, Sakai T. Linear elasticity of polymer gels in terms of negative energy elasticity. Polym J. 2021;53:1293–303.

Annable T, Buscall R, Ettelaie R, Whittlestone D. The rheology of solutions of associating polymers: Comparison of experimental behavior with transient network theory. J Rheol. 1993;37:695–726.

Annable T, Buscall R, Ettelaie R. Network formation and its consequences for the physical behaviour of associating polymers in solution. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 1996;112:97–116.

Nakagawa S, Yoshie N. Star polymer networks: a toolbox for cross-linked polymers with controlled structure. Polym Chem. 2022;13:2074–107.

Mark JE, Sullivan JL. Model networks of end-linked polydimethylsiloxane chains. I. Comparisons between experimental and theoretical values of the elastic modulus and the equilibrium degree of swelling. J Chem Phys. 1977;66:1006–11.

Sakai T, et al. Design and Fabrication of a High-Strength Hydrogel with Ideally Homogeneous Network Structure from Tetrahedron-like Macromonomers. Macromolecules. 2008;41:5379–84.

Fujiyabu T, et al. Tri-branched gels: Rubbery materials with the lowest branching factor approach the ideal elastic limit. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabk0010.

Yoshikawa Y, Sakumichi N, Chung U, Sakai T. Connectivity dependence of gelation and elasticity in AB-type polymerization: an experimental comparison of the dynamic process and stoichiometrically imbalanced mixing. Soft Matter. 2019;15:5017–25.

Fujiyabu T, Yoshikawa Y, Chung U, Sakai T. Structure-property relationship of a model network containing solvent. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2019;20:608–21.

Chassé W, Lang M, Sommer J-U, Saalwächter K. Cross-Link density estimation of PDMS networks with precise consideration of networks defects. Macromolecules. 2012;45:899–912.

Gusev AA, Schwarz F. Molecular dynamics study on the validity of miller–macosko theory for entanglement and crosslink contributions to the elastic modulus of end-linked polymer networks. Macromolecules. 2022;55:8372–83.

Schwenke K, Lang M, Sommer J-U. On the Structure of star–polymer networks. Macromolecules. 2011;44:9464–72.

Lang M. Elasticity of phantom model networks with cyclic defects. ACS Macro Lett. 2018;7:536–9.

Kumar KS, Lang M. Reversible Networks Made of Star Polymers: Mean-Field Treatment with Consideration of Finite Loops. Macromolecules. 2023;56:7166–83.

Furuya T, Koga T. Molecular simulation of networks formed by end-linking of tetra-arm star polymers: Effects of network structures on mechanical properties. Polymer. 2020;189:122195.

Yasuda Y, Morita H. Structural Analysis of the Linear Elasticity of End-Cross-Linked Star Elastomers with a Number of Trapped Entanglements via Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Macromolecules. 2024;57:4804–16.

Kremer K, Grest GS. Dynamics of entangled linear polymer melts: A molecular-dynamics simulation. J Chem Phys. 1990;92:5057–86.

Duering ER, Kremer K, Grest GS. Relaxation of randomly cross-linked polymer melts. Phys Rev Lett. 1991;67:3531–4.

Thompson AP, et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput Phys Commun. 2022;271:108171.

Japan Association For Chemical Innovation, Computer Simulation of Polymeric Materials: Applications of the OCTA System. (Springer Singapore, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0815-3

Svaneborg C, Everaers R, Grest GS, Curro JG. Connectivity and entanglement stress contributions in strained polymer networks. Macromolecules. 2008;41:4920–8.

Masubuchi Y, Ishida T, Koide Y, Uneyama T. Phantom chain simulations for the fracture of star polymer networks with various strand densities. Soft Matter 10.1039.D4SM00726C, https://doi.org/10.1039/D4SM00726C (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Young Scientists (No. 22K14740). We thank Frank Kitching, MSc., from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by The University of Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Akagi, Y., Fujimoto, K. & Yasuda, Y. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations and structural analysis of end-linked polymer networks under different cross-linking protocols. Polym J 57, 1183–1194 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01089-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01089-7