Abstract

Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) is an autosomal dominant vascular disorder characterized by mucocutaneous telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in internal organs. It is mainly caused by heterozygous pathogenic variants in ENG, ACVRL1 or SMAD4. Somatic mosaic mutations in the functional allele of HHT-causing genes have been identified in skin telangiectasias and AVMs of HHT patients, which is suspected to drive formation of telangiectasias and AVMs. Our objective was to further support and clarify the pathogenetic mechanism of HHT lesion genesis by analysing several HHT lesion biopsies; all from a single HHT patient caused by a germline deletion of the entire ACVRL1 gene. Deep exome sequencing was performed on DNA from multiple fresh tissue biopsies from the same HHT patient; six hepatic AVM samples, two macroscopic normal hepatic control samples, and three mucocutaneous telangiectasia biopsies. Somatic mosaic lesion-specific ACVRL1 variants were identified in four hepatic AVM samples and in one telangiectasia. Two different somatic variants (c.293A>G; p.Asn98Ser and c.1378-199C>A) were identified in several lesions from the same liver. Additionally, a third lesion-specific somatic variant (c.614T>G; p.Val205Gly) was identified in one skin telangiectasia. We identified in total 3 different somatic variants, which are expected to contribute to the pathogenesis of HHT vascular lesions. These data further support the second-hit pathophysiological mechanism to explain the multifocality of vascular lesions in HHT. This is the first report to perform deep sequencing on multiple samples from both several visceral AVMs and telangiectasias originating from one single HHT patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hereditary Haemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) (OMIM 187300, 600376 and 175050) is an autosomal dominant vascular disorder characterized by abnormal blood vessel formation, due to genetic mutations in the TGF-beta pathway, which regulate angiogenesis and vasculogenesis [1]. This condition leads to a predisposition for telangiectatic lesions in cutaneous and mucosal tissue, and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) in visceral organs, including liver, lungs and brain. AVMs can cause serious complications such as hemorrhage, anemia, and hemodynamic alterations. The clinical manifestations of HHT are highly heterogeneous, even within families, and the disorder is multifocal with high, however age-dependent, penetrance.

Most HHT AVMs are believed to be congenital, whereas mucocutaneous telangiectasias increase in number over the years, predominantly in adult life [2,3,4].

HHT is mainly associated with germline pathogenic variants in three genes: ENG (Endoglin, OMIM 131195), ACVRL1 (activin receptor-like kinase 1, OMIM 601284) and SMAD4 (OMIM 600993), all of which play important roles in the regulation of angiogenesis and vascular integrity [5,6,7].

The HHT diagnosis is based on the clinical consensus ‘Curaçao Criteria’, and fulfilling at least 3 of 4 criteria are diagnostic of HHT [8]. It can be problematic to base the diagnosis only on clinical examination, due to the age-dependent nature of the disorder, hence genetic testing is often a useful part of the HHT diagnostics.

Originally, HHT was thought to follow a haploinsufficiency model, which was proposed because individuals with a single germline mutation in either ENG or ACVRL1 exhibited clinical features of HHT, suggesting that the reduction in gene dosage alone could cause the disease manifestations [9,10,11]. However, haploinsufficiency does not comprehensively explain the clinical heterogeneity and multifocality observed in HHT patients. Therefore, for years, it has been postulated that the clinical heterogeneity and multifocality observed in HHT patients, could be due to the existence of additional triggers, including a somatic loss of the second allele, via a Knudsonian two-hit mechanism [12]. According to this model, individuals inherit a germline mutation in one allele of a disease-associated gene (first hit), predisposing them to the condition. A second, acquired genetic alteration of the wild-type copy of the gene (second hit) is required for HHT lesions to develop. The germline variant and somatic second hit in combination result in the functional impairment of the corresponding gene-encoded protein and subsequent development of AVMs. HHT would, according to this model, be dominantly inherited, but recessively expressed following a second post-zygotic somatic genetic or epigenetic event. The variability of the time of occurrence of this second event could explain the variable age of onset of the various HHT lesions. Endothelial cells are considered the target cell in HHT.

In 2019, Snellings et al. showed that biallelic loss of ENG or ACVRL1, in fact, may be required in the development of HHT telangiectasia [13]. In examining multiple dermal telangiectasias from several HHT patients, they identified low-frequency somatic mutations in the same gene as the causal germline mutation, and they showed that independent lesions from a single patient harbor lesion-specific somatic mutations. In 2024 and 2025, three studies, investigating HHT AVM samples, identified low-frequency somatic mutations in tissue from multiple AVMs from multiple HHT patients carrying germline variants in ENG, ACVRL1 or SMAD4 [14,15,16].

It has been suggested that, besides somatic mutations in the wildtype HHT gene allele, there could be other triggers involved in generating the vascular lesions. These triggers may be mechanical trauma, inflammation, vascular injury, angiogenic stimuli, shear stress, and modifier genes [17]. These triggers may act as secondary events in combination with the somatic second hit to provoke HHT lesions, or they may precede the somatic mutation and contribute to its induction [18].

In other multifocal vascular disorders, similar to HHT, multiple publications have demonstrated somatic second hits as part of the disease mechanism to explain the development of multifocal vascular lesions. These include somatic mutations in RASA1 in lesions from patients with capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation (CM-AVM) and TIE2 (TEK) somatic mutations in lesions from patients with venous malformations [19, 20].

To our knowledge, this is the first report to perform deep sequencing on multiple samples from both several visceral AVMs and telangiectasias originating from one single HHT patient.

Material and methods

Patient

A female, age 40, with clinically and genetically diagnosed HHT, was evaluated at the HHT centre at Odense University Hospital, exhibited hepatic arteriovenous malformations (HAVM) grade 4 according to the Buscarini score [21]. Previous Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis had identified an ACVRL1 whole-gene deletion. Right sided heart catheterization showed signs of high output cardiac failure, but no pulmonary hypertension (CO 9.8 L/min, CI 5.3 L/min/m2, PAP 19 mmHg, PCWP 11 mmHg). The patient did not have pulmonary AVMs but experienced epistaxis, anaemia and iron deficiency, which was corrected with laser treatment and iron supplement. The patient underwent three treatments of Bevacizumab, however, due to continuing rise in especially ALP and ALAT, and severe side effects, the patient was listed for a liver transplant. The liver transplantation was performed without complications.

Sample collection

Biopsies from the hepatic vascular lesions were collected immediately after liver-extraction. A total of 8 biopsies were collected, six from objectively AVM affected areas (G142-1-6) (two biopsies each from liver segments 5, 6, and 7) and two from macroscopic normal tissue (G142-N1-2) (from liver segment 4). Segments 5 and 7 had macroscopic more severe AVM formation than segment 6. Figure 1 shows the liver after extraction and a CT scan of the liver.

a Extracted liver displaying visible arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and multiple focal nodular hyperplasias (FNH). b Coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan in the arterial phase, showing the liver before transplantation with clearly visible intrahepatic arteries and multiple FNH lesions. Biopsies were taken from marked areas: (1) HAVM in hepatic segment 7 (sample ID: G142-3 and G142-4), (2) HAVM in hepatic segment 6 (sample ID: G142-1 and G142-2), (3) HAVM in hepatic segment 5 (sample ID: G142-5 and G142-6), and (4) macroscopic normal tissue in hepatic segment 4 (sample ID: G142-N1 and G142-N2). Created with BioRender.com.

Biopsies from the nasal and cutaneous telangiectasias were collected by an experienced rhinologist in local anesthesia and contained macroscopically visible telangiectasias. The biopsies were collected as close to the telangiectatic lesion as possible ensuring inclusion of the lesion in the biopsy. All AVM and mucocutaneous telangiectasia samples were immediately preserved in RNAlater solution (ThermoFisher Scientific). An EDTA-blood sample was collected.

DNA extraction

Blood samples: DNA was purified using the Maxwell® RSC DNA Blood DNA Kit (Promega, Sweden).

Tissue, skin and mucosal samples: DNA was purified using the Maxwell® RSC DNA Tissue DNA Kit, AS1610 (Promega, Sweden).

Exome sequencing and Data Analysis

Sample preparation was performed using 400 ng DNA after Covaris mechanical fragmentation. Library preparation was conducted following the Twist Exome 2.0 hybridization protocol (Twist Bioscience, Inc.). Validated libraries were pooled and sequenced in paired-end mode 2 × 150 bp the on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, Inc.). The sequencing quality criteria obliged a minimum coverage of 20x in 95% of the coding regions. The mean coverage was around 1200X.

The alignment and variant calling was performed using Illumina DRAGEN Bio.IT Platform (Illumina, Inc.). Sequencing data was aligned to reference GRCh38. Variant calling was performed by using DRAGEN DNA pipeline somatic mode and tumor-normal mode. Copy number variant (CNV) analysis was performed by using VarSeq 2.5.0 (GoldenHelix, Inc.). Large somatic loss of heterozygosity was estimated by manually evaluation of the ratio value of copy number calculated by VarSeq.

VarSeq 2.5.0 was used for variant annotation and downstream filtering of the variants.

Variant detection and evaluation

We specifically searched for variants in the ACVRL1 gene. Clinical significance of the variants were evaluated according to ClinGen Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia Expert Panel Specifications to the ACMG/AMPVariant Interpretation Guidelines for ACVRL1 Version 1.0.0 (https://cspec.genome.network/cspec/ui/svi/doc/GN135) [22]. The Genome Aggregation Database v.4.1.0 (GnomAD) was used to evaluate the allele frequency of the variants in the background population. For missense variants, the prediction software SIFT, Polyphen2.0, FATHMM, Mutation Taster and MutationAssessor were used. For splicing prediction SpliceSiteFinder-like, MaxEntScan and SpliceAI values were used.

To rule out involvement of other genetic variants a panel of HHT-related genes (ENG, ACVRL1, SMAD4, RASA1, EPHB4, GDF2) was examined.

Results

We examined the hepatic AVM and telangiectasia samples with deep exome sequencing, focusing on mainly the ACVRL1 gene, to investigate the presence and nature of second-hit somatic mutations in the ACVRL1 gene. Further, a blood sample from the patient was examined with deep exome sequencing.

Germline ACVRL1 whole-gene deletion

The germline heterozygous whole-gene deletion of ACVRL1 was previously identified with MLPA analysis [23]. In this study, exome sequencing confirmed the deletion and showed it to be a heterozygous large deletion, approximately 130 kb, (NC_000012.12: g.(51847454_51888187)_(52014201_52014694)del), including the entire ACVRL1 gene (pathogenic – C5) and four additional genes (ACVR1B, ANKRD33, RNU5-574P and TAMALIN), of which none are OMIM morbid genes. One break point locates upstream of ANKRD33, and the other breakpoint locates in the intron before the last coding exon in TAMALIN. The germline ACVRL1 deletion was confirmed in all hepatic AVM and mucocutaneous telangiectasia samples, in the two macroscopically normal hepatic samples, and in the blood sample, consistent with the patient’s HHT diagnosis.

Identification of somatic second-hit variants

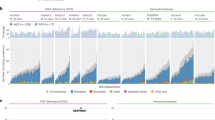

Four out of six hepatic AVM samples and one of three mucocutaneous telangiectasias showed mosaic somatic variants in the ACVRL1 gene (Table 1 and Fig. 2). These mutations were in trans with the germline deletion and not identified in the blood sample (Fig. 3).

Interestingly, two distinct somatic variants (ACVRL1, NM_000020.3: c.293A>G; p.Asn98Ser and ACVRL1, NM_000020.3: c.1378-199C>A) were identified in multiple lesions from different segments of the liver (Fig. 2). The somatic variant p.Asn98Ser was identified in AVM tissues in segment 5 and in segment 7 of the liver. Additionally, the somatic variant c.1378-199C>A was identified in other AVM biopsies from segments 5 and 7. A third somatic variant (ACVRL1; NM_000020.3: c.614T>G; p.Val205Gly) was identified in a cutaneous telangiectasia removed from the forehead of the patient (Fig. 2). Biopsy tissue details, in addition to germline and somatic variant findings are listed in Table 1.

ACVRL1 somatic mosaicism ranged from 2.2–8.0%, with an average ACVRL1 local total read depth of 825X. However, as one allele is deleted, due to the germline ACVRL1 whole-gene deletion, that equals a total read depth of around 1650X. The mean total exome coverage in the biopsy samples was around 1130X.

Manual evaluation of large somatic loss of heterozygosity did not reveal any large somatic deletions in the region of ACVRL1.

None of the samples had pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (C4-C5) identified using an in silico panel of additional HHT-related genes (ENG, SMAD4, RASA1, EPHB4, GDF2).

Finally, to rule out the possibility that the somatic variants were germline mosaic variants, we conducted deep sequencing of DNA extracted from peripheral blood DNA from the patient. All the detected somatic variant was absent from the blood. The mean total exome coverage in the blood sample was 864X.

Classification of somatic second-hit variants

ACVRL1, NM_000020.3: c.293A>G; p.Asn98Ser is a heterozygous missense variant previously described as pathogenic or likely pathogenic and causing HHT in several publications [24,25,26]. The variant is not described in GnomAD 4.1.0, thus not observed in around 800,000 healthy individuals, and predicted damaging by 4 out of 5 prediction software. In ClinVar the variant is classified twice as pathogenic and once as a variant of uncertain significance. Based on ACMG guidelines (PS1, PM2_supporting, PP3) the variant is classified as likely pathogenic (C4).

The putative splice site variant in ACVRL1, NM_000020.3: c.1378-199C>A has not previously been described, in either Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD®), GnomAD 4.1.0 or in ClinVar. The variant is predicted pathogenic in SpliceSiteFinder-like, MaxEntScan, NNSPLICE and GeneSplicer, while predicted benign in SpliceAI. Based on ACMG guidelines (PM2, PP3) the variant is classified as a variant of uncertain significance (C3). Further investigation would be required in order to reclassify the variant as likely pathogenic or pathogenic.

ACVRL1; NM_000020.3: c.614T>G; p.Val205Gly is a heterozygous missense variant previously described as a pathogenic variant causing HHT in several publications [27, 28]. The variant is not described in GnomAD 4.1.0 or in ClinVar and predicted damaging by 3 out of 5 prediction software. SpliceAI predicts a donor loss effect with delta score of 0.55. Based on ACMG guidelines (PS1, PM2_supporting, PP3) the variant is classified as likely pathogenic (C4).

Discussion

In analysing several biopsies from both hepatic AVMs and cutaneous telangiectasias, all from a single HHT patient, we show independent mosaic lesion-specific somatic ACVRL1 variants in trans with the germline ACVRL1 deletion. We identified three different independent lesion-specific somatic variants, of which two were observed in multiple hepatic AVM samples. Our findings support the two-hit hypothesis in the pathogenesis of HHT-related AVMs and telangiectasias, indicating that a somatic mutation in the remaining wild-type copy of the inherited mutant gene is a necessary event in HHT lesion formation.

The identification of two distinct somatic variants in different segments of the liver highlights the heterogeneity of the somatic variant landscape and show that AVMs within the same organ can arise independently and have multiple somatic second-hit variants. Remarkably the HHT vascular lesions are both localized and tissue specific. The localized formation of vascular lesions could be explained by sporadic somatic variants generating biallelic mutations [18]. Besides somatic variants in the wildtype HHT gene allele, other triggers may contribute to vascular lesions, such as mechanical trauma, inflammation, vascular injury, angiogenic stimuli, shear stress, and modifier genes. These may act alongside or lead to the somatic second hit that provokes HHT lesions.

The identified second-hit variants were located in trans with the germline deletion, meaning they occur on the allele not affected by the germline deletion, leading to complete functional loss of ACVRL1 -encoded protein in the endothelial cells. It can be challenging to clearly confirm whether the identified germline and somatic variants are located in trans however, in this study, we can establish that conclusively as the germline variant is a whole-gene deletion. In this study the Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) was 2.2–8.0%, with the highest VAF in AVM tissue compared to the telangiectasias, possibly because visceral AVMs are larger than cutaneous telangiectasias allowing the biopsies to include a higher proportion of vascular tissue. Because the germline mutation in our study involves a complete gene deletion, the variant allele frequency of any second-hit somatic mutation reflects the full proportion of mutant cells in the sample. This contrasts with germline point mutations, where the VAF corresponds to roughly half the number of mutant cells due to the presence of one wild-type allele. Consequently, in this study we have an advantageous germline variant/deletion. Further, all biopsies inevitably include other tissue types, which will not be affected by the mutations that are located in the AVM. Further, it is well known that collection of HHT-associated lesion specimens is challenging. Biopsies are collected based on manual tissue inspection and evaluation. It is challenging to ensure a high proportion of endothelial cells in the tissue. If the endothelial cell proportion in the biopsy is low, the chance of detecting the second-hit somatic mutation decreases significantly, which also may explain the variation in VAF. In this study, we did not identify somatic second-hit in hepatic segment 6 which exhibited less severe AVM formations, possibly indicating that the tissue was less representative of the pathological state or had a lower degree of somatic mosaicism, than possible to identify with the used methodology.

Nevertheless, the VAFs we detected are relatively high, likely due to our careful collection of samples to better represent a larger proportion of relevant tissue, as these samples were specifically collected for this study. Further, our samples were fresh tissue, to avoid the bias that formalin-fixed-paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue would impose on genetic analysis.

Interestingly, this study identified two different somatic variants (c.293A>G: Asn98Ser and NM_000020.3: c.1378-199C>A) both observed in different liver segments (segments 5 and 7), which highlights the heterogeneity of mutational events and suggest that different AVMs within the same organ can arise independently. The presence of two postzygotic variants with differing VAFs in the same tissue suggests two individual clones with a clonal expansion process, demonstrating subclonal heterogeneity. This gives rise to thoughts concerning the timing of the occurrence of the somatic second-hit variants. In contrast to most organs, the liver is a homogenous mass, which in the embryo derives from the endoderm during gastrulation, this forms into the hepatic bud, which later, through proliferation and differentiation, develops into the mesenchymal liver components [29]. The vasculature in the liver arises in gestational week 10 deriving from the epithelium, the final vasculature is a result of a tightly controlled development, involving both angiogenesis and vasculogenesis [30]. As this study identified two different somatic variants in different areas of the liver, one can contemplate, that these variants must have happened during the development of the organ, allowing for the clonal expansion individually through the liver vasculature. It is deemed unlikely that the same somatic variant should be identified in different areas of the liver, if the variants were developed after the liver has fully developed. The occurrence of two independent somatic mutations in the liver AVM, may be partly responsible of the large size of the hepatic AVM in this patient. Moreover, the findings in this study support that hepatic AVM formation can be congenital. This is further substantiated by the previous findings of infantile intrahepatic vascular malformations [31]. The mucocutaneous telangiectasias, however, are acquired through life, increasing in numbers over the years, predominantly in adult life and in locations susceptible to sun exposure or mechanical trauma.

In our study, we detected second-hit somatic variants in the ACVRL1 gene in 5 out of 9 samples. Two hepatic AVM samples, G142-3 and G142-6, share the same C4 variant, another two hepatic AVM samples, G142-4 and G142-5, share the same C3 variant, and one cutaneous telangiectasias sample has a different C4 variant. We did not identify second-hit somatic variants in 4 out of 9 samples; 2 hepatic AVM samples, 1 cutaneous lesion and 1 nasal mucosal telangiectasia. That is in line with previous similar studies that also did not demonstrate somatic variants in every HHT lesion studied [13,14,15,16], which could be due to tissue heterogeneity, as addressed above, or due to methodological limitations.

We used NGS exome sequencing to identify second-hit somatic variants. Exome sequencing covers the protein-coding regions of the genome and the nearby intronic regions, but it does not cover deep intronic areas, promoters, enhancers, or other regulatory regions. This could be one reason why second-hit mutations were not identified in all of the samples. Our patient has a germline heterozygous deletion of the entire ACVRL1 gene, which complicates the detection of somatic copy number variants (CNVs). As a result, a somatic CNV may have gone undetected. The same limitation applies to somatic structural chromosome abnormalities, as the exome sequencing is not ideal for detecting those either. Somatic variant detection depends heavily on the coverage. Both sensitivity and specificity increase with coverage. The mean coverage of our exome sequencing is around 1,130X, which is quite high, but this is not always sufficient for somatic variant detection. Our method’s sensitivity is lower for variants with very low allele frequency. Lastly, variant allele frequency is also influenced by the proportion of endothelial cells in the tissue, which varies with sampling.

Beyond pathogenic CNVs/single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in the ACVRL1 gene, other mechanisms that sequencing cannot detect may lead to gene deactivation. Somatic Loss of Heterozygosity has been reported, and furthermore, abnormal DNA methylation may promote gene silencing [15, 16, 32, 33].

Conclusion

This is, to our knowledge, the first report to perform deep sequencing on multiple samples from both several visceral AVMs and telangiectasias originating from one single HHT patient.

Our study demonstrates mosaic, lesions-specific somatic ACVRL1 variants in trans with the germline ACVRL1 deletion across several lesion biopsies from a single HHT patient. This supports that a somatic mutation in the remaining wild-type copy of the inherited mutant gene is a necessary event in HHT lesion formation.

This study highlights the complexity of the genetic pathophysiology associated with HHT.

Understanding the mechanisms underlying AVM development in HHT has profound implications for the development of targeted therapies aimed at preventing or mitigating the vascular abnormalities characteristic of HHT.

Data availability

The small somatic variant calls generated from exome sequencing of the study samples are publicly available in the European Variation Archive (EVA) at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB96743. The raw sequencing data generated during the current study are not made publicly available due to patient privacy, legal and ethical restrictions, in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Danish national legislation governing the protection of personal data. The data include identifiable genetic information and thus cannot be shared publicly.

References

van den Driesche S, Mummery CL, Westermann CJ. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: an update on transforming growth factor beta signaling in vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:20–31.

Beslow LA, Krings T, Kim H, Hetts SW, Lawton MT, Ratjen F, et al. De novo brain vascular malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Pediatr Neurol. 2024;155:120–5.

Hyldahl SJ, El-Jaji MQ, Schuster A, Kjeldsen AD. Skin and mucosal telangiectatic lesions in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia patients. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1497–505.

Letteboer TG, Mager HJ, Snijder RJ, Lindhout D, Ploos van Amstel HK, Zanen P, et al. Genotype-phenotype relationship for localization and age distribution of telangiectases in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:2733–9.

McAllister KA, Grogg KM, Johnson DW, Gallione CJ, Baldwin MA, Jackson CE, et al. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat Genet. 1994;8:345–51.

Gallione CJ, Repetto GM, Legius E, Rustgi AK, Schelley SL, Tejpar S, et al. A combined syndrome of juvenile polyposis and hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia associated with mutations in MADH4 (SMAD4). Lancet. 2004;363:852–9.

Johnson DW, Berg JN, Gallione CJ, McAllister KA, Warner JP, Helmbold EA, et al. A second locus for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia maps to chromosome 12. Genome Res. 1995;5:21–8.

Shovlin CL, Guttmacher AE, Buscarini E, Faughnan ME, Hyland RH, Westermann CJ, et al. Diagnostic criteria for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu-Osler-Weber syndrome). Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:66–7.

Abdalla SA, Letarte M. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: current views on genetics and mechanisms of disease. J Med Genet. 2006;43:97–110.

Pece-Barbara N, Cymerman U, Vera S, Marchuk DA, Letarte M. Expression analysis of four endoglin missense mutations suggests that haploinsufficiency is the predominant mechanism for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2171–81.

Pece N, Vera S, Cymerman U, White RI Jr, Wrana JL, Letarte M. Mutant endoglin in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1 is transiently expressed intracellularly and is not a dominant negative. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2568–79.

Knudson AG Jr. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:820–3.

Snellings DA, Gallione CJ, Clark DS, Vozoris NT, Faughnan ME, Marchuk DA. Somatic mutations in vascular malformations of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia result in Bi-allelic loss of ENG or ACVRL1. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105:894–906.

Whitehead KJ, Toydemir D, Wooderchak-Donahue W, Oakley GM, McRae B, Putnam A, et al. Investigation of the genetic determinants of telangiectasia and solid organ arteriovenous malformation formation in Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT). Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:7682.

DeBose-Scarlett E, Ressler AK, Gallione CJ, Sapisochin Cantis G, Friday C, Weinsheimer S, et al. Somatic mutations in arteriovenous malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia support a bi-allelic two-hit mutation mechanism of pathogenesis. Am J Hum Genet. 2024;111:2283–98.

DeBose-Scarlett E, Ressler AK, Friday C, Prickett KK, Roberts JW, Gossage JR, et al. Arteriovenous malformation from a patient with JP-HHT harbours two second-hit somatic DNA alterations in SMAD4. J Med Genet. 2025;62:281–8.

Bernabeu C, Bayrak-Toydemir P, McDonald J, Letarte M. Potential second-hits in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3571.

Arthur HM, Roman BL. An update on preclinical models of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: Insights into disease mechanisms. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:973964.

Macmurdo CF, Wooderchak-Donahue W, Bayrak-Toydemir P, Le J, Wallenstein MB, Milla C, et al. RASA1 somatic mutation and variable expressivity in capillary malformation/arteriovenous malformation (CM/AVM) syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170:1450–4.

Cai R, Liu F, Liu Y, Chen H, Lin X. RASA-1 somatic “second hit” mutation in capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation. J Dermatol. 2018;45:1478–80.

Buscarini E, Danesino C, Olivieri C, Lupinacci G, De Grazia F, Reduzzi L, et al. Doppler ultrasonographic grading of hepatic vascular malformations in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia - results of extensive screening. Ultraschall Med. 2004;25:348–55.

DeMille D, McDonald J, Bernabeu C, Racher H, Olivieri C, Cantarini C, et al. specifications of the ACMG/AMP variant curation guidelines for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia genes—ENG and ACVRL1. Human Mutat. 2024;2024:3043736.

Torring PM, Brusgaard K, Ousager LB, Andersen PE, Kjeldsen AD. National mutation study among Danish patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Clin Genet. 2014;86:123–33.

Prigoda NL, Savas S, Abdalla SA, Piovesan B, Rushlow D, Vandezande K, et al. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: mutation detection, test sensitivity and novel mutations. J Med Genet. 2006;43:722–8.

Brakensiek K, Frye-Boukhriss H, Malzer M, Abramowicz M, Bahr MJ, von Beckerath N, et al. Detection of a significant association between mutations in the ACVRL1 gene and hepatic involvement in German patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Clin Genet. 2008;74:171–7.

Sanchez-Martinez R, Iriarte A, Mora-Lujan JM, Patier JL, Lopez-Wolf D, Ojeda A, et al. Current HHT genetic overview in Spain and its phenotypic correlation: data from RiHHTa registry. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:138.

Komiyama M, Ishiguro T, Yamada O, Morisaki H, Morisaki T. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in Japanese patients. J Hum Genet. 2014;59:37–41.

Kitayama K, Ishiguro T, Komiyama M, Morisaki T, Morisaki H, Minase G, et al. Mutational and clinical spectrum of Japanese patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. BMC Med Genom. 2021;14:288.

Douarin NM. An experimental analysis of liver development. Med Biol. 1975;53:427–55.

Gouysse G, Couvelard A, Frachon S, Bouvier R, Nejjari M, Dauge MC, et al. Relationship between vascular development and vascular differentiation during liver organogenesis in humans. J Hepatol. 2002;37:730–40.

Gallego C, Miralles M, Marin C, Muyor P, Gonzalez G, Garcia-Hidalgo E. Congenital hepatic shunts. Radiographics. 2004;24:755–72.

Nishiyama A, Nakanishi M. Navigating the DNA methylation landscape of cancer. Trends Genet. 2021;37:1012–27.

Wong VC, Chan PL, Bernabeu C, Law S, Wang LD, Li JL, et al. Identification of an invasion and tumor-suppressing gene, Endoglin (ENG), silenced by both epigenetic inactivation and allelic loss in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2816–23.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to our patient that donated multiple samples to this study.

Funding

Funding for this project is covered by the HHT centre in Odense. Open access funding provided by Odense University Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study/conceptualization: PDH, QH, KB, MJL, JK, ADK, PMT. Contributed patient materials: PDH, ADF, JK, NAS, ADK. Performed the experiments/methodology: QH, KB. Analyzed the data: QH, KB, MJL, PMT. Supervision: QH, PMT. Writing–original draft: PDH, QH, PMT. Writing–review and editing: PDH, QH, KB, MJL, BL, ADF, MSK, JK, NAS, ADK, PMT.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The project has been approved by the Danish Ethics Committee, project-ID S-20230085. Information about the project was provided both orally and in writing, and a written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Darre Haahr, P., Hao, Q., Brusgaard, K. et al. Multiple lesion-specific somatic mutations and bi-allelic loss of ACVRL1 in a single patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Eur J Hum Genet 34, 236–242 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01962-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01962-2

This article is cited by

-

Advancing genomic medicine: Guidelines, risk scores, and disease discovery

European Journal of Human Genetics (2026)