Abstract

Aim

To investigate the effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy (MSDP) on the development of dental conditions in human offspring, as presented in current literature.

Methods

Observational studies from six databases (MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science and Maternity and Infant Care (MIC)) were systematically searched in July 2024. Articles were screened based on their investigation of the effect of MSDP on the development of dental conditions in offspring. Methodological quality was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS), while the quality of evidence was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) approach.

Results

A total of 17 articles were included in this review, focusing on the primary dental developmental outcomes: molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH), enamel defects (other than MIH), missing teeth, dental eruption, and short root anomaly. Due to high levels of heterogeneity among the studies, meta-analysis was not performed. The majority of studies demonstrated good methodological quality (n = 10), with three assessed as fair and four as poor. The quality of evidence was categorised, with three outcomes receiving a low quality of evidence classification, and tooth eruption and short root anomaly being classed as very low quality. Statistically significant associations between MSDP and each dental outcome had varied results across studies. Most studies concluded an association between MSDP and conditions such as enamel defects (other than MIH), missing teeth, and short root anomaly. Some studies found associations with MIH, while the majority found no link between MSDP and tooth eruption in offspring.

Conclusion

This review suggests a potential association between MSDP and dental development conditions in offspring. However, due to the low quality of evidence and inconsistencies in findings across observational studies, a definitive association cannot be drawn. Further, novel and high-quality research is needed to understand the impact MSDP on dental development in offspring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Conditions affecting the orofacial complex can significantly hamper the quality of life of individuals1. Understanding the potential causes of these conditions is critical in developing education and early intervention strategies for parents and their babies. It is accepted that in addition to genetic variations, complex combinations of environmental and maternal exposures to noxious stimuli can disrupt molecular pathways during early development stages, ultimately contributing to conditions arising from defects in tooth morpho/agenesis2. Maternal smoking during pregnancy (MSDP) is recognized as a human teratogen and risk factor for adverse health outcomes and developmental disorders, including those involving the craniofacial complex3. In 2021, one in 12 Australian women reported smoking during pregnancy4. This is particularly significant given that tooth development begins around the sixth week in utero and continues throughout gestation and the first years of life. Disturbances during these stages have the potential to affect tooth number, shape and mineralization5.

Tooth development, or odontogenesis, involves the formation of three hard tissues—enamel, dentine, and cementum—along with the neurovascular dental pulp6 Odontogenesis begins at around six weeks in utero and continues into the first few months after birth7. This process is divided into four stages, classified based on their histological appearance: initiation which begins at six weeks in utero, bud (eight weeks in utero), cap (nine weeks in utero), and bell stages (11 weeks in utero)8. The eruption of the primary dentition can vary but typically starts from 8.6 ± 2.0 (mean ± SD) months and continues until 27.9 ± 4.4 months9, while their permanent counterparts replace them between 6.0 ± 2.0 years and 12.0 ± 1.9 years10. The crowns of primary teeth mineralize by one year, whilst permanent teeth complete crown formation from 8 to 9 year ± 9.0 (mean ± SD) months (excluding third molars)11,12. Root formation continues two to three years after tooth eruption12.

Disruptions during these critical windows of tooth development and enamel formation often can only be detected later through chemical, physical and radiographic examination. Impacting processes within these stages may have the potential to influence the number or morphological characteristics of developing teeth. For instance, an interruption during the initiation phase may affect dental placode formation thus affecting tooth number. Likewise, key morphological features of the tooth, such as cusp position and crown size, are determined in the bell stage and thus could be affected if disrupted13. Alterations to the normal development of the tooth may also manifest as enamel hypomineralisation or irregular tooth eruptions, both of which significantly impact on the health of the individual’s dentition and quality of life14.

Despite a general understanding of how tooth development progresses, there are gaps in research that directly connect MSDP to specific dental anomalies. While conditions like caries15,16,17 and cleft lip/palate18,19 are reported to be associated with MSDP, other dental abnormalities such as hypodontia, irregular tooth eruption, short roots, molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH), and other enamel defects remain underexplored. Hypodontia is the failure of development of six teeth or less20. Irregular tooth eruption describes an eruption pattern that differs to the statistical average population data collected by previous literature for deciduous and permanent dentition21,22. Short root anomaly is classed when the root-crown ratio is ≤1.023. MIH and enamel defects are qualitative defects causing hypomineralisation of enamel on the surface24,25. These anomalies can significantly affect a child’s oral function and aesthetics, with potential long-term impacts on self-confidence and quality of life1. Given that these conditions can arise from disruptions to the tooth development process in utero, MSDP may have an association with their occurrence.

MSDP has long been recognized as a public health issue, linked to adverse outcomes such as low birthweight, preterm birth, miscarriage, and ectopic pregnancies26. As recognized earlier, disruption to any of the numerous phases of odontogenesis has the potential to result in abnormalities in the dentition. Research directly examining MSDP as a primary factor influencing dental abnormalities has been limited and inconsistent. Given these uncertainties, this review aims to comprehensively assess current literature to determine whether MSDP has a direct effect on the development of teeth, focusing on anomalies such as deviations in root and crown shape, tooth number, hard tissue mineralization, and eruption patterns.

Materials and methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines27,28,29.

Developing a focused question

Using the PICO format, a focused research question was developed to include the population of human offspring, intervention group of pregnancies where the mother smoked during, comparator being pregnancies where the mother did not smoke and our outcome being the presence of dental developmental conditions. The research question for this systematic review was “What is the effect of smoking during pregnancy on the occurrence of dental development conditions in offspring when compared to non-smoking controls?”.

Selection criteria

This review included observational studies such as cross-sectional, longitudinal/cohort studies and case-control studies performed on human participants. Studies published from 2000 – July 2024, written in the English language and have the full text available were included. Assessing a dental developmental outcome and including participant groups where the mother smoked during pregnancy and those that did not were also considered as inclusion criteria. The age of inclusion for the offspring in studies was from 0 to 19 years. Articles that were reviews or editorials, did not include a dental development outcome or were not assessing the outcome in offspring of mothers who either smoked or did not during pregnancy were excluded.

Search strategy

A search strategy was developed to cover three main parameters of our PICO question: smoking, mothers/pregnant women, and dental developmental conditions. In total, six electronic databases were searched, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, Web of Science and Maternity and Infant Care (MIC) using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 1. Grey literature and articles from bibliographies were also screened for inclusion.

Data extraction and synthesis

Articles captured in the database search were exported into Covidence. After removing the duplicates, title and abstract screening was completed by two independent reviewers (HT and MM) with any discrepancies resolved through discussion and where necessary with the help of a third reviewer (SL). Articles shortlisted in title and abstract screening progressed to full-text review using the above listed inclusion and exclusion criteria by two independent reviewers (HT and SL). Any disagreements between the two reviewers were solved through discussion or with the assistance of a third reviewer (MM). Data from selected articles was extracted by two independent reviewers (HT and MM) with any discrepancies resolved through a third reviewer (SL), into a predesigned extraction file using Microsoft Excel (Version 16.88). Extracted data included study design, population characteristics, outcomes measured and statistical results including study estimates, confidence intervals and p values. Extracted data was assessed for suitability to conduct meta-analysis, however, due to the perceived high heterogeneity of the primary studies, this was not completed. Sources of heterogeneity from included studies involved the differences in study designs, variability in each studies definition of maternal smoking as the exposure and differences between how individual outcomes were measured across studies. Additionally, individual studies differed in their adjustment for confounders further limiting the ability for meta-analysis to be performed.

Quality assessment

To assess the methodological quality of each article, the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used30. Assessment of both case-control and cohort studies was completed using a selection score from 0 to 4, comparability score from 0 to 2 and an outcome score from 0 to 330. Assessment of methodological quality in cross-sectional studies was conducted using an adapted form of the NOS to best reflect these studies31. As such, selection criteria could score from 0 to 3, comparability from 0 to 2 and outcomes from 0 to 2. All three reviewers (HT, HM, SL) completed quality assessment so that each article was assessed by two independent reviewers with the third to assist in solving any discrepancies.

A final quality score was assigned to each article to correlate with the quality of methodology. Good quality was defined as three or four points in selection and two points in comparability and two or three points in outcome/exposure domain. Fair quality included two points in selection and one or two points in comparability and two or three points in outcome/exposure. Finally, Poor quality consisted of zero or one point in selection or zero points in comparability or zero to one point in outcome/exposure domain (Reproduced from18).

An assessment of the quality of evidence for each identified dental developmental outcome was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework32. Outcomes were assessed independently by three reviewers (HT, MM and SL), any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Quality of evidence for the included studies was assessed initially based on the study type and then adjusted based on the performance in outcomes of methodological limitations, indirectness, imprecision, inconsistency and publication bias. Scores for each category were graded as either not serious, borderline or serious. The combined results of these were then used to give an overall rating to the evidence quality using the categories high, moderate, low or very low.

Results

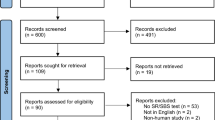

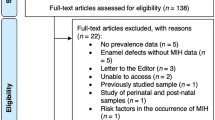

Study selection

Figure 1 presents the review process in a PRISMA flowchart. From the six databases searched, 4167 articles were identified, no additional studies were identified through manual or grey literature searches. Following duplicate removal, 2872 citations had their title and abstract screened with 39 progressing to full-text review. Of the articles screened during full-text, 22 were excluded for the following reasons: 11 for assessing the wrong outcome, 10 for using the wrong study design, and one due to the full-text not being available (Appendix 2). As such, 17 articles were included in the final review presented.

Characteristics of studies

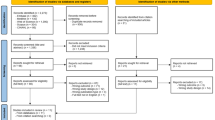

The characteristics of included studies is summarised in Table 1. Studies were grouped based on the outcome assessed. Of the included studies, six evaluate the effect of MSDP on MIH, three assessed enamel defects other than MIH, two investigated missing teeth, five eruption timing, and one investigated short root anomaly. Categorising MIH studies separate to other enamel defect studies aimed to facilitate accurate comparisons between these specific outcomes. Studies grouped under enamel defects other than MIH included examination of hypomineralised second primary molars (HSPM), enamel hypoplasia and enamel opacities. Articles were published from 2007 until 2023. In total, there were four case-control, three cross-sectional and ten cohort studies. The number of participants was defined as the number of offsprings who were assessed for the dental development outcomes which varied from 102 to 5536. The age of participants was defined as the age recorded of the offspring participating in the study which ranged from six months to 19 years. Of the included studies, most examined smoking at any stage of pregnancy, two studies examined smoking during specific trimester of pregnancy and were noted. The dose of cigarette smoking was only investigated in two studies whilst most simply examined any amount of smoking.

Of the included studies, 13 defined smoking during pregnancy as any period, whilst Silva et al.33 examined it at each trimester. Boyer et al.34 recorded information on smoking at the beginning of the study, Aktoren et al.22 only recorded smoking during the first trimester of gestation and Hanioka et al.35 categorised smoking as occurring every day or sometimes/ceased partway. Finally, 15 of the 17 studies recorded smoking as either a binary yes or no, whilst only two studies reported the volume of cigarette consumption during the pregnancy.

Confounders

The confounders for each included study as listed by the authors is evident in Table 2. Of the included studies, seven did not mention any adjustments for confounders in their analysis. The remaining studies adjusted for a variety of confounders including sex, age, socioeconomic status and some pre and peri-natal maternal factors.

Molar incisor hypomineralisation

The outcomes of the six studies investigating MIH all compared the presence of this defect in offspring and MSDP (Table 3). The results varied, with an equal number of studies demonstrating a significant association or an increased incidence of MIH and MSDP as those showing no association. Two studies reported a statistically significant difference in the presence of MIH in offspring between the mothers who smoked during pregnancy and those who did not36,37. An increased incidence of MIH in offspring exposed to MSDP was also found (OR = 2, 95% CI 0.8–4.4)34. In contrast, Lim et al. found that, after adjusting to confounders, the incidence of MIH in offspring of smoking mothers attenuated to the null (OR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.608–1.38)38. Franco et al. found no significant association between MIH and MSDP in molars alone and molars and incisors measured together (p = 0.15 and p = 0.58, respectively)39. In addition, a retrospective study concluded that there was no significant association between smoking status during pregnancy and MIH in children born in both urban and rural settings (p = 0.602 and p = 0.853, respectively)40.

Enamel defects other than MIH

Across the three included studies, all demonstrated an association between MSDP and enamel defects that were not MIH, specifically enamel hypoplasia (Table 3). The study by Silva et al.33 which analysed data based on specific periods of smoking throughout pregnancy demonstrated that maternal smoking during the second and third trimesters were statistically significant (p = 0.01 and 0.005, respectively)33. However, their analysis based on smoking at any time during pregnancy, as well as smoking limited to the first trimester, was not statistically significant (p = 0.225 and p = 0.185, respectively)33. They also combined the second and third trimester and analysed using two models (with and without the covariate of birth vitamin D data), the first model showed no statistical significance (p = 0.055), whilst the second model indicated a significant association (p = 0.007)33. Vello et al. examined both enamel hypoplasia and enamel opacity as outcomes for enamel defects41. While the presence of enamel opacities was not statistically significant (p = 0.274), enamel hypoplasia alone showed a significant association with MSDP (p = 0.028). However, the combined effect of both these defects was not significant (p = 0.246)41. A case control study conducted by Ford et al. also concluded that there was a significant association between MSDP and the combined enamel defects measured, compared to controls (p = 0.007)42.

Missing teeth (hypodontia)

The prevalence of hypodontia and MSDP was seen to be significant and associated with the number of cigarettes consumed (Table 3). A case control study reported that smoking at any level during pregnancy was significantly associated with the presence of missing teeth in the offspring (p = 0.004)43. However, when examining the dose relationship by categorising the participants as either one to nine cigarettes per day or smoking 10+ cigarettes per day, only smoking 10+ cigarettes per day was statistically significant (p = 0.007) with the presence of hypodontia, whilst smoking one to nine cigarettes per day was not (p = 0.232)43. Results presented by Kang et al.44 also found that, after adjusting for confounders, smoking 6+ cigarettes per day was statistically significantly associated with missing teeth (p = 0.024) even though a similar observation was not present in the participants who smoked 1-5 cigarettes per day. However, the authors noted an odds ratio greater than 1 for this group (OR = 2.8, 95% CI: 0.52-15.06)44.

Eruption

The investigation of dental eruption patterns provided varied results (Table 3). Whilst some studies found an association between MSDP and altered dental eruption, the majority did not. A prospective cohort study conducted in Brazil showed that there was no statistically significant association between MSDP and any observed tooth emergence patterns in offspring and MSDP45. Similarly, Hanioka et al. found no significant association between high or medium doses of smoking and early tooth eruption, both in crude results and after adjusting for confounders (p = 0.888, p = 0.631)35. Another retrospective cohort study also reported no statistically significant association between MSDP and either early or late-stage eruption (p = 0.561, p = 0.632)22. However, Ntani et al. reported statistically significant associations, reporting that MSDP was associated with early eruption of the first tooth (p = 0.035), a greater number of teeth present at one year old (p = <0.001), and a higher likelihood of having more than 16 teeth by the age of two (p = 0.002) in children whose mothers smoked during pregnancy21.

Short root anomaly

Only one study investigated the effect of MSDP on root development and identified a significant association with MDSP (Table 3). This study reported both crude and adjusted results, indicating that MSDP was significantly associated with short root anomaly (p = 0.002, p = 0.004, respectively)23. The adjusted odds ratio showed that offspring of mothers who smoked were more likely to develop short root anomaly compared to non-smokers (OR = 4.95, 95% CI: 1.65–14.79)23.

Quality assessment of included studies

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)

The studies included were categorsied based on their study design using the NOS, as shown in Table 4. Of these studies, ten were rated as good quality, three as fair quality, and four as poor quality. The studies rated as poor quality failed to meet the required standards either in the comparability of subjects or in the measurement of study outcomes.

GRADE scale

The overall quality of evidence for each dental development outcome is summarised in Table 5. The GRADE scale analysis indicated that the evidence related to MIH, enamel defects, and missing teeth was of low quality, whilst studies examining eruption patterns and short root anomaly were classified as very low quality. Overall, the studies presented showed a lack of high quality evidence based on methodological limitations, indirectness, imprecision, inconsistency and publication bias.

Discussion

Dental developmental conditions describe anomalies that may affect the number, shape, size, or colour of teeth46 and can significantly impact quality of life1. With MSDP already being linked to conditions such as caries15 and cleft-lip/palate18, along with Australia’s high prevalence of maternal smoking4, investigation into the effect of MSDP on tooth development is necessary. This review aimed to investigate the effect of MSDP on dental developmental conditions affecting tooth shape, size, number, roots and hard tissue development. From the literature reviewed, associations between MSDP and enamel defects and hypodontia were identified, however quality of the evidence was generally low, with some studies indicating a link with MIH as well.

Current evidence suggests a plausible mechanism between MSDP and dental anomalies involves increased oxidative stress47,48 and placental hypoxia49. Both passive and active smoking during pregnancy can adversely affect the neural crest cells responsible for forming deciduous teeth, potentially preventing their maturation and resulting in hypodontia47,48. Chronic foetal hypoxia due to nicotine exposure may lead to developmental delays, further inhibiting proper tooth development13,50. Additionally, nicotine can disrupt the deposition of enamel and dentine matrices, leading to inadequate mineralisation and resulting in hypomineralisation and enamel defects51.

Several studies have demonstrated a positive association between MSDP and MIH34,36,37. These results are in contrast to a recent review examining the aetiology of MIH, which, following a meta-analysis, reported no significant association between MSDP and MIH52. Notably, four out of the six MIH studies included in this review were published after the systematic review examining the aetiology of MIH by Garot et al., with three of these findings contributing to the observed significant positive associations36,37 or an increased incidence of MIH34. This discrepancy may stem from the inclusion of more recent studies in our review. In addition to MIH, other enamel defects were also positively associated with MSDP33,41,42. With both conditions involving the defects in the development of enamel it is unsurprising that a correlation exists. Specifically, significant association between enamel hypoplasia and MSDP were found41, particularly with maternal smoking during the second or third trimesters33. Animal studies have further demonstrated that smoking negatively impacts ameloblast function, which is the cell type responsible for enamel development53. These mechanisms highlight the potential adverse effects of nicotine and smoking on enamel formation, supporting the associations identified between MSDP, enamel defects and possibly MIH.

An association between hypodontia and MSDP is also supported by the literature43,44. Both a New Zealand case-control study43 and a Japanese cohort study44 indicate a dose-dependent relationship between hypodontia and MSDP. Specifically, Al-Ani et al. identified that smoking ten or more cigarettes per day increases the risk of hypodontia43, whilst Nakagawa Kang et al. reported a similar association but with six or more cigarettes44. The presence of a dose-dependent relationship strengthens the evidence of a causal relationship between MSDP and hypodontia rather than a mere association. Identification of this biological gradient aligns with the parameters from Bradford Hills criteria for causation54. This relationship suggest that elevated levels of smoking-related toxins may heighten the risk of hypodontia, potentially through increased oxidative stress damaging neural crest cells13,47,48,50.

Most studies did not find a significant association between MSDP and tooth eruption patterns. The aetiology of dental eruption patterns is likely to be a complex interconnected process between both environment and genes55. A recent review indicates that the Runt-related transcription factor-2 (RUNX2) gene plays a key role in dental eruption56, with delays in eruption previously linked to malnutrition and low birthweight57. It has been hypothesised that smoking during the first trimester which coincides with the initiation, bud and cap stages of odontogenesis, may lead to accelerated eruption timings51. Despite most studies showing no association, two studies reported a significant association21,58, consistent with previous research59. The overall evidence for this relationship was rated very low, largely due to the reliance on self-reported data from mothers regarding eruption timing and a lack of consensus on measuring maternal smoking, which may have contributed to conflicting results. Only a single study examining short root anomalies was identified, which showed an association with MSDP, however, the lack of comparability among studies rendered the evidence very low quality. Smoking has been shown to induce DNA methylation of the EVC2 protein complex60, which mediates epithelial-mesenchymal interactions that influence root length61,62. While some evidence suggests an association a possible association between MSDP and short roots, the lack of studies limits clinical applicability.

A key strength of this review is that it incorporates a range of different dental developmental conditions. The comprehensive search strategy used across databases allowed for an extensive search of the research and inclusion of a wide range of studies that fit the inclusion criteria. However, a meta-analysis was not conducted due to the heterogeneity in the study designs, differences in exposure and outcome definitions, outcome assessments, and analyses to adjust for the confounders. Instead, the quality of evidence was graded using a subjective measure. The studies included were graded as having either low or very low quality of evidence, an additional limitation in clinical applicability of these results. Factors significant in the poor methodological quality of studies included the risk of recall and social desirability bias. Studies relied on the self-reporting of both smoking data and in some cases the dental outcome itself. Additionally, many studies did not adjust data for key confounders including passive smoking, maternal health status or other pre and peri-natal factors such as alcohol consumption. Inconsistency in methodologies and poor comparability between studies is a significant factor in improving the clinical relevance of these results. An additional limitation of this review includes the lack of inter-rater reliability measures for assessment of agreement between reviewers during study selection and quality assessment. Further, the lack of sub-group analysis is also a limitation of this review. Sub-group analysis was not feasible due to the heterogeneity across the included studies. Specifically, there were inconsistencies in adjusting for confounders, insufficient details to allow for stratification of data by key factors including age, disease severity and exposure measurements. The incorporation of subgroup analysis could have provided further insights into the differences in effect sizes across different contexts and strengthened the rationale behind the narrative synthesis. As mentioned earlier, disruptions in tooth development at different stages can influence the type of dental anomalies in offspring8. However, there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions on this aspect as only one included study examined the effects of smoking during different stages of pregnancy. Therefore, the lack of reporting of these time periods is a significant limitation of the included studies.

The importance of identifying risk factors for the development of dental conditions is critical to shaping clinical care. However, without the development of a universal measure of determining MSDP, the clinical applicability of results presented in this review is limited. Future research should focus on improving the methodological inconsistencies of current study designs to provide more high quality evidence. Reporting the specific periods of maternal smoking and dose-dependent relationships will improve the understanding on the association between MSDP and dental anomalies in offspring. Additionally, prospective cohort study designs in replacement of retrospective data collection will reduce the potential bias and improves the quality of evidence. Improvements to the measurement of maternal smoking with biomarker validation instead of reliance on self-reported data may also increase the quality of evidence and clinical applicability of these results. In addition to standardised measures of MSDP, the standardisation of the dental anomaly measurements will reduce heterogeneity and improve feasibility of meta-analyses in future. Further, adjustments for confounders such as passive smoking exposure and other environmental pollutants, genetic predisposition to anomalies, and maternal pre and peri-natal factors should be implemented to increase quality of evidence generated by future research.

In conclusion, this systematic review demonstrates that prenatal exposure to smoking does pose significant risks in the development of hypodontia and enamel defects in offspring. However, the strength of this evidence remains limited due to the methodological inconsistencies across studies. To ensure conclusive and accurate clinical interpretation of these results, further high-quality and well-controlled research is necessary to validate the risk of MSDP on development of dental conditions.

Data availability

The data supporting this article can be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

References

Geirdal A, Saltnes SS, Storhaug K, Åsten P, Nordgarden H, Jensen JL. Living with orofacial conditions: psychological distress and quality of life in adults affected with Treacher Collins syndrome, cherubism, or oligodontia/ectodermal dysplasia-a comparative study. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:927–35.

Brook AH. Multilevel complex interactions between genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors in the aetiology of anomalies of dental development. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54:S3–17.

Gilbert-Barness E. Teratogenic causes of malformations. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2010;40:99–114.

Health AIo, Welfare. National Core Maternity Indicators. Canberra: AIHW; 2023.

Ali S, Farooq I, Khurram SA Tooth Development. An Illustrated Guide to Oral Histology 2021. p. 1-13.

Gulabivala K, Ng YL. Tooth organogenesis, morphology and physiology. In: Gulabivala K, Ng Y-L, editors. Endodontics. 4th ed: Mosby; 2014. p. 2–32.

Kwon H-JE, Jiang R. Development of Teeth. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences: Elsevier; 2018.

Hovorakova M, Lesot H, Peterka M, Peterkova R. Early development of the human dentition revisited. J Anat. 2018;233:135–45.

Woodroffe S, Mihailidis S, Hughes T, Bockmann M, Seow WK, Gotjamanos T, et al. Primary tooth emergence in Australian children: timing, sequence and patterns of asymmetry. Aust Dent J. 2010;55:245–51.

Ripa LW, Leske GS, Sposato AL, Simon GA, Moresco TV. Chronology and sequence of exfoliation of primary teeth. J Am Dent Assoc. 1982;105:641–4.

Liversidge HM. The assessment and interpretation of Demirjian, Goldstein and Tanner’s dental maturity. Ann Hum Biol. 2012;39:412–31.

Nelson SJ. Wheeler’s Dental Anatomy, Physiology and Occlusion-E-Book: Wheeler’s Dental Anatomy, Physiology and Occlusion-E-Book: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014.

Larsen LG, Clausen HV, Jønsson L. Stereologic examination of placentas from mothers who smoke during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:531–7.

Berkovitz BK, Holland GR, Moxham BJ. Oral Anatomy, Histology and Embryology E-Book: Oral Anatomy, Histology and Embryology E-Book: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

Zhong Y, Tang Q, Tan B, Huang R. Correlation between maternal smoking during pregnancy and dental caries in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oral Health. 2021;2:673449.

Akinkugbe AA, Brickhouse TH, Nascimento MM, Slade GD. Prenatal smoking and the risk of early childhood caries: A prospective cohort study. Preventative Med Rep. 2020;20:101201.

Sobiech P, Olczak-Kowalczyk D, Spodzieja K, Gozdowski D. The association of maternal smoking and other sociobehavioral factors with dental caries in toddlers: A cross-sectional study. Front Pediatrics. 2023;11:1115978.

Fell M, Dack K, Chummun S, Sandy J, Wren Y, Lewis S. Maternal cigarette smoking and cleft lip and palate: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofacial J. 2022;59:1185–200.

Martelli DRB, Coletta RD, Oliveira EA, Swerts MSO, Rodrigues LAM, Oliveira MC, et al. Association between maternal smoking, gender, and cleft lip and palate. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;81:514–9.

Al-Ani AH, Antoun JS, Thomson WM, Merriman TR, Farella M. Hypodontia: an update on its etiology, classification, and clinical management. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:9378325.

Ntani G, Day PF, Baird J, Godfrey KM, Robinson SM, Cooper C, et al. Maternal and early life factors of tooth emergence patterns and number of teeth at 1 and 2 years of age. J Developmental Orig Health Dis. 2015;6:299–307.

Aktoren O, Tuna E, Guven Y, Gokcay G. A study on neonatal factors and eruption time of primary teeth. Community Dent Health. 2010;27:52.

Sagawa Y, Ogawa T, Matsuyama Y, Nakagawa Kang J, Yoshizawa Araki M, Unnai Yasuda Y, et al. Association between smoking during pregnancy and short root anomaly in offspring. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:11662.

Weerheijm KL, Jälevik B, Alaluusua S. Molar–Incisor Hypomineralisation. Caries Res. 2001;35:390–1.

Almuallem Z, Busuttil-Naudi A. Molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH) – an overview. Br Dent J. 2018;225:601–9.

Avşar TS, McLeod H, Jackson L. Health outcomes of smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period: an umbrella review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:254.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n71.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj. 2021;372:n160.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000.

Patra J, Bhatia M, Suraweera W, Morris SK, Patra C, Gupta PC, et al. Exposure to second-hand smoke and the risk of tuberculosis in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 observational studies. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001835.

Murad MH, Mustafa RA, Schünemann HJ, Sultan S, Santesso N. Rating the certainty in evidence in the absence of a single estimate of effect. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2017.

Silva M, Kilpatrick N, Craig J, Manton D, Leong P, Burgner D, et al. Etiology of hypomineralized second primary molars: a prospective twin study. J Dent Res. 2019;98:77–83.

Boyer E, Monfort C, Lainé F, Gaudreau É, Tillaut H, Bonnaure-Mallet M, et al. Prenatal exposure to persistent organic pollutants and molar-incisor hypomineralization among 12-year-old children in the French mother-child cohort PELAGIE. Environ Res. 2023;231:116230.

Hanioka T, Ojima M, Tanaka K, Taniguchi N, Shimada K, Watanabe T. Association between secondhand smoke exposure and early eruption of deciduous teeth: A cross-sectional study. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2018;16.

Bagattoni S, Carli E, Gatto M, Gasperoni I, Piana G, Lardani L. Predisposing factors involved in the aetiology of Molar Incisor Hypomineralization: a case-control study. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2022;23:116–20.

Lee D-W, Kim Y-J, Oh Kim S, Choi SC, Kim J, Lee JH, et al. Factors associated with molar-incisor hypomineralization: a population-based case-control study. Pediatr Dent. 2020;42:134–40.

Lim Q-Y, Taylor K, Dudding T. The effects of modifiable maternal pregnancy exposures on offspring molar-incisor hypomineralisation: A negative control study. Community Dental Health. 2022.

Franco MM, Ribeiro CC, Ladeira LL, Thomaz EBAF, Alves CMC. Pre-and perinatal exposures associated with molar incisor hypomineralization: Birth cohort, Brazil. Oral Dis. 2024;30:3431–9.

Souza J, Costa-Silva C, Jeremias F, Santos-Pinto L, Zuanon ACC, Cordeiro. RdCL. Molar incisor hypomineralisation: possible aetiological factors in children from urban and rural areas. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2012;13:164–70.

Velló M, Martínez-Costa C, Catalá M, Fons J, Brines J, Guijarro-Martínez R. Prenatal and neonatal risk factors for the development of enamel defects in low birth weight children. Oral Dis. 2010;16:257–62.

Ford D, Seow WK, Kazoullis S, Holcombe T, Newman B. A controlled study of risk factors for enamel hypoplasia in the permanent dentition. Pediatr Dent. 2009;31:382–8.

Al-Ani A, Antoun J, Thomson W, Merriman T, Farella M. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with offspring hypodontia. J Dent Res. 2017;96:1014–9.

Nakagawa KJ, Unnai Yasuda Y, Ogawa T, Sato M, Yamagata Z, Fujiwara T, et al. Association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and missing teeth in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:4536.

Bastos JL, Peres MA, Peres KG, Barros AJ. Infant growth, development and tooth emergence patterns: a longitudinal study from birth to 6 years of age. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:598–606.

Puri P, Shukla S, Haque I. Developmental dental anomalies and their potential role in establishing identity in post-mortem cases: a review. Med-Leg J. 2019;87:13–8.

Sakai D, Dixon J, Achilleos A, Dixon M, Trainor PA. Prevention of Treacher Collins syndrome craniofacial anomalies in mouse models via maternal antioxidant supplementation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10328.

Matsuzaki M, Haruna M, Ota E, Murayama R, Yamaguchi T, Shioji I, et al. Effects of lifestyle factors on urinary oxidative stress and serum antioxidant markers in pregnant Japanese women: A cohort study. Biosci Trends. 2014;8:176–84.

Jauniaux E, Burton GJ. Morphological and biological effects of maternal exposure to tobacco smoke on the feto-placental unit. Early Hum Devlopment. 2007;83:699–706.

Ozturk F, Sheldon E, Sharma J, Canturk KM, Otu HH, Nawshad A. Nicotine exposure during pregnancy results in Persistent Midline Epithelial seam with improper palatal fusion. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:604–12.

Samani D, Ziaei S, Musaie F, Mokhtari H, Valipour R, Etemadi M, et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and early childhood dental caries in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24:781.

Garot E, Rouas P, Somani C, Taylor G, Wong F, Lygidakis N. An update of the aetiological factors involved in molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH): a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry. 2022:1–16.

Dong Q, Wu H, Dong G, Lou B, Yang L, Zhang L. The morphology and mineralization of dental hard tissue in the offspring of passive smoking rats. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:1005–13.

Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? : Sage Publications; 1965.

AlQahtani S. Chapter 7 - Dental age estimation in fetal and children. In: Adserias-Garriga J, editor. Age Estimation: Academic Press; 2019. p. 89–106.

Xin Y, Zhao N, Wang Y. Multiple roles of Runt-related transcription factor-2 in tooth eruption: bone formation and resorption. Arch Oral Biol. 2022;141:105484.

Robinow M. The eruption of the deciduous teeth (factors involved in timing). J Tropical Pediatrics Environ Child Health. 1973;19:200–5.

Żądzińska E, Sitek A, Rosset I. Relationship between pre-natal factors, the perinatal environment, motor development in the first year of life and the timing of first deciduous tooth emergence. Ann Hum Biol. 2016;43:25–33.

Rantakallio P, Mäkinen H. Number of teeth at the age of one year in relation to maternal smoking. Ann Hum Biol. 1984;11:45–52.

Miyake K, Kawaguchi A, Miura R, Kobayashi S, Tran NQV, Kobayashi S, et al. Association between DNA methylation in cord blood and maternal smoking: The Hokkaido Study on Environment and Children’s Health. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5654.

Zhang H, Takeda H, Tsuji T, Kamiya N, Kunieda T, Mochida Y, et al. Loss of function of Evc2 in dental mesenchyme leads to hypomorphic Enamel. J Dent Res. 2017;96:421–9.

Nakatomi M, Hovorakova M, Gritli-Linde A, Blair HJ, MacArthur K, Peterka M, et al. Evc regulates a symmetrical response to Shh signaling in molar development. J Dent Res. 2013;92:222–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank the support and expertise of the academic liaison librarian, Mrs. Kanchana Ekanayake in helping develop the search strategy for this review.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TNJ and SN developed the concept and formulated the research question. HT, MM and SL searched the databases, filtered articles, assessed bias, and drafted the manuscript. TNJ, SN and HT reviewed and edited the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiernan, H., Masud, M., Lange, S. et al. The association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and dental development in offspring: a systematic review. Evid Based Dent 26, 157 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-025-01168-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-025-01168-x