Abstract

Background

Children with brain tumours often suffer from late diagnosis, impacting cure rates and risk of permanent sequelae. Ophthalmological symptoms are common, and we aimed to investigate the frequency, diagnostic interval, and prognostic value of early-onset ophthalmological brain tumour signs.

Methods

The study is based on data from national Danish health registries and medical files from hospitals and private ophthalmologists collected from all children diagnosed with a primary brain tumour in Denmark during 2007–2017.

Results

Among 437 included children, 51.7% (n = 226) had ophthalmological tumour signs prior to diagnosis, and 10.8% (n = 47) had ophthalmological symptoms as their initial tumour manifestation. The most common ophthalmological signs in total before diagnosis were reduced visual acuity (n = 73; 16.7%), diplopia (n = 65; 14.9%), abnormal optic nerve (n = 59; 13.5%), and strabismus (n = 50; 11.4%). The median time from initial symptom onset to diagnosis was 12.6 weeks for all children, 15.9 weeks for those with ophthalmological symptoms as their initial tumour sign (p = 0.28), and 12.5 weeks for those with ophthalmological tumour signs at any time before diagnosis (p = 0.71). Children with ophthalmological signs before diagnosis had a higher risk of death (HR: 2.11; 95% CI: 1.32–3.39; p = 0.002).

Conclusions

Ophthalmological tumour signs are frequent in children with brain tumours, and the diagnostic interval is long regardless of ophthalmological tumour signs being present or not. Taken together with the higher risk of death in the group with ophthalmological tumour signs, this study emphasises the importance of the ophthalmological assessment to ensure timely diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Brain tumours are the most frequent solid tumours in children, accounting for 20–25% of childhood neoplasms with an estimated annual incidence of 3–5 per 100.000 children [1]. Furthermore, brain tumours are the leading cause of cancer-related mortality in children and the leading non-accidental cause of childhood death in high-income countries [2,3,4]. The five-year survival rate has improved to 70–80% in past decades [1, 3]. However, many survivors experience a reduced quality of life due to long-term sequelae such as cognitive, endocrine, and visual impairment [2, 5,6,7,8,9,10].

Children with brain tumours often suffer from a diagnostic delay [2, 7, 11], which may be associated with an even worse prognosis [7, 8, 12, 13]. An increased interest in earlier detection has emerged in recent years [11, 14, 15]. The time from the onset of the initial tumour sign to the diagnosis is defined as the total diagnostic interval (TDI). Following the introduction of HeadSmart in the UK, a paediatric brain tumour awareness campaign, the median TDI was reduced from 14.4 weeks to 6.7 weeks [14, 16]. Reducing TDI improves the opportunities for earlier and better treatment and, thus, a better prognosis by lowering subsequent morbidity and perhaps even mortality [7, 8, 12, 13, 17].

Initial symptoms often tend to vary and be nonspecific with headache and vomiting being the most common, followed by ophthalmological symptoms [2, 11, 16, 18]. Common eye symptoms, such as reduced visual acuity and strabismus, may not initially be acknowledged as a tumour sign owing to the frequency of these conditions in otherwise healthy children [7, 15, 19, 20].

Enhanced knowledge of ophthalmological tumour signs can potentially reduce the diagnostic interval [7, 21,22,23] and the aim of this study is consequently to investigate the frequency, diagnostic interval, and prognostic value of ophthalmological tumour signs in Danish children 0–18 years of age with primary brain tumours.

Materials and methods

This study is a national retrospective study. Using data from the Danish Childhood Cancer Registry (DCCR), we identified all children aged 0–18 years diagnosed with a central nervous system (CNS) tumour in Denmark from 2007 to 2017. DCCR contains information on all children (<18 years) diagnosed with cancer in Denmark [24]. We extracted data from DCCR, including patient ID, the date of diagnosis, tumour location, histopathology, survival status, and date of death (if applicable). We identified a total population of 528 children and obtained hospital files from two years before the diagnosis. The Danish National Health Insurance Service Registry (NHSR) holds information regarding the citizens’ visits to the Danish health care system. Hence, we collected medical files from private ophthalmologists who had examined the children up to two years prior to the diagnosis. The last day of follow-up was the 1st of May 2019.

After reviewing all the medical files, we excluded 91 children, resulting in a total population of 437. Exclusion criteria included tumours with extracerebral origin (n = 26), not having a neoplastic tumour (n = 17), no connection to the Danish health care system at the time of diagnosis (n = 6), lack of sufficient data (n = 5), age >18 years old when diagnosed (n = 5), and diagnosis before 2007 (n = 3). Further, 29 children were excluded because they had a genetic tumour predisposition syndrome that was already known before the diagnosis (neurofibromatosis type 1 n = 22; tuberous sclerosis n = 3; von Hippel-Lindau syndrome n = 2; neurofibromatosis type 2 n = 1; Gorlin syndrome n = 1). These children are enrolled in a tumour screening program, and the events leading to the diagnosis were, therefore, not comparable to the rest of the group. Children whose tumour predisposition syndromes were not known at the time of the brain tumour diagnosis were included.

Only tumour signs present before the diagnosis were registered. Both subjective complaints and clinical findings were included as tumour signs if they were verified by the clinical examination and/or not found to be caused by another more likely reason. Whether to include a sign as a tumour sign was decided by two medical specialists (one a paediatric ophthalmologist) after a thorough evaluation of the information given in the medical files. If there was doubt about whether to include the sign, another paediatric ophthalmologist was consulted. Parents and the children themselves were the primary observers of initial symptoms. Clinical findings were identified by ophthalmologists, general practitioners (GPs), and paediatricians. Reduced visual acuity included both monocular and binocular impairment. The tests used were Teller and Cardiff for the youngest children, figure charts and Standard Snellen charts with letters for school-age children. Symptoms with onset more than two years before the diagnosis were not recorded unless clearly stated as a tumour sign in the medical files. We registered the initial tumour sign for every child, which was the symptom or clinical finding with the earliest onset. In the analyses, we differentiated between initial signs and signs occurring at any time before the diagnosis (total tumour signs which also included initial tumour signs). The group of children with initial tumour signs being ophthalmological are referred to as the IOS group.

TDI was defined as the interval from the initial tumour sign onset to the diagnosis (defined as the date of tumour identification with CT or MR imaging). Age, tumour grade, and location were subdivided (Table 1), and tumour signs were subcategorised (Table 2).

Statistical analyses were performed with R (version 4.1.0). Differences in median time to diagnosis were calculated with the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis tests (Table 3). The chi-squared test and the t-test were applied for other subgroup comparisons as appropriate.

The relative importance of the various tumour signs for particularly long TDI (three horizons: TDI > 1 month; TDI > 3 months; TDI > 1 year) in each of the three age groups was investigated with dominance analysis. In such analysis, the relative contributions of the tumour signs to the coefficient of determination (R2) in a multivariable regression model were calculated by averaging the increase in R2 due to an addition of a specific sign to the model, over all possible model configurations [25]. Subsequently, the top 3 signs in each analysis were evaluated in a multivariable logistic regression model to determine the direction of the effect, i.e. odds ratio (OR) < 1 implies shorter TDI when the sign is present and identifies the sign as a helpful diagnostic sign, while OR > 1 implies longer TDI when the sign is present and identifies it as not facilitating the diagnosis within the specified timeframe (Supplementary Table 1).

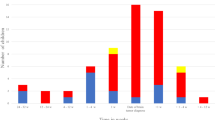

The associations between ophthalmological tumour signs and mortality were evaluated in multivariable Cox regression models. In these models, the occurrence of ophthalmological tumour signs before diagnosis (in three categories: initial sign, subsequent sign, none) was associated with the incidence of (all-cause) death with hazard ratios (HRs) (Table 4). The log-rank test was used to compare Kaplan–Meier survival curves (Fig. 1).

The study was approved by the Danish Patient Safety Authority (3-3013-2800/1) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (VD-2019-84). The study was evaluated by the Regional Research Ethical Committee of the Capital Region, Copenhagen, Denmark, and did not require ethics approval. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

In total, 437 children with a primary brain tumour were included in the study (Table 1). The gender distribution was equal, and the median age at diagnosis was 8.0 years. In our population, 10.8% (n = 47) of the children had an ophthalmological tumour sign as their initial sign (IOS group) and 51.7% (n = 226) had at least one ophthalmological tumour sign at any time before they were diagnosed (Table 1). In total, 37.5% (n = 164) of the children were examined by an ophthalmologist before the diagnosis. Among the 226 children with ophthalmological tumour signs, 53.1% (n = 120) were examined by an ophthalmologist before diagnosis (Table 1).

Ophthalmological tumour signs

The most common initial ophthalmological tumour signs (IOS group) were reduced visual acuity (n = 14; 3.2%) and strabismus (n = 14; 3.2%) (Table 2). Diplopia (n = 7; 1.6%), nystagmus (n = 4; 0.9%), and proptosis (n = 4; 0.9%) were less common initial ophthalmological signs. Reduced visual acuity (n = 73; 16.7%) and strabismus (n = 50; 11.4%) were also among the most frequent ophthalmological tumour signs in total prior to diagnosis (Table 2).

Diagnostic interval and ophthalmological tumour signs

TDI was 12.6 weeks for the 431 children with symptoms. For the IOS group, the median TDI was 15.9 weeks compared with 12.3 weeks for children with non-ophthalmological initial signs (p = 0.28) (Table 3). There was no difference in median time to diagnosis for children with ophthalmological tumour signs at any time before the diagnosis and those without (12.5 weeks vs 12.6 weeks; p = 0.71).

The ophthalmological signs with the longest median diagnostic interval (time from onset of the sign to diagnosis in children presenting the sign, regardless of when it appeared before diagnosis) were proptosis (47.5 days), reduced visual acuity (46 days) and strabismus (20.5 days) (Table 2). Papilledema was the sign with the shortest diagnostic interval overall (median 0 days; mean 1 day).

Relative diagnostic importance

Strabismus was one of the initial ophthalmological tumour signs with the highest relative importance (RI) related to the diagnostic interval (Supplementary Table 1). As the initial tumour sign in both the oldest and youngest children, strabismus was a sign that precluded a diagnostic delay of >1 year (OR = 0). In the youngest children, strabismus as an initial tumour sign hindered quick diagnosis, i.e., a TDI < 1 month was not likely (OR = 2.89). Among the oldest children, diplopia had a top-3 highest RI among all tumour signs. For analyses with diagnostic delay >1 month, >3 months, and >1 year, diplopia was an initial tumour sign with ORs in the interval 0–0.20, thereby a sign facilitating faster diagnosis.

General tumour signs, sex, age and tumour grade, and location

More girls than boys had initial ophthalmological tumour signs (p = 0.001) as well as ophthalmological signs at any time before diagnosis (p = 0.02) (Supplementary Table 2). Girls had a mean number of total tumour signs before the diagnosis of 4.0, compared with 3.7 for boys (p = 0.04). Nearly 90% (n = 383) of the children had a minimum of two tumour signs at the time of diagnosis. The most common general tumour signs were headache (n = 255; 58.4%), nausea/vomiting (n = 245; 56.1%), change of behaviour (n = 196; 44.9%), and ataxia/vertigo/balance problems (n = 170; 38.9%) (Table 2). The distribution of children with ophthalmological signs at any time before diagnosis according to age groups differed significantly, as proportionally more children had ophthalmological manifestations with increasing age (p = 0.03) (Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, there was a significantly higher distribution of high-grade tumours among the children with ophthalmological signs at any time before diagnosis (p = 0.046) (Supplementary Table 2). A significantly higher proportion of high-grade tumours were located infratentorial rather than supratentorial (p < 0.001). High-grade tumours and death were highly correlated (p < 0.001).

Survival

In an adjusted multivariable Cox regression analysis for our total population, children with ophthalmological tumour signs before diagnosis (but not as initial signs, i.e. subsequent) had a significantly higher risk of death (HR: 2.11; 95% CI: 1.32–3.39; p = 0.002) (Table 4 and Fig. 1). Among children with TDI ≤ 30 days, both initial and subsequent ophthalmological signs were significantly correlated with a higher risk of death (HR: 4.87; 95% CI: 1.41–16.83; p = 0.012 and HR: 2.80; 95% CI: 1.25–6.29; p = 0.013). In addition, children with a TDI between 91 and 365 days showed a significant association between ophthalmological signs before diagnosis (subsequent) and death (HR: 4.06; 95% CI: 1.11–14.88; p = 0.035).

Discussion

This study provides an overview of ophthalmological and general tumour signs prior to the diagnosis in a nationwide population of 437 children diagnosed with a primary brain tumour during an 11-year period in Denmark. We found a high prevalence of ophthalmological tumour signs before the diagnosis (51.7%), with 10.8% of the population presenting with one of these signs as their initial symptom (IOS group). Reduced visual acuity (16.7%), diplopia (14.9%), abnormal optic nerve (13.5%), and strabismus (11.4%) were the most common ophthalmological signs prior to diagnosis. Having ophthalmological tumour signs was associated with an increased risk of death.

Compared with our 51.7% with ophthalmological tumour signs at any time before diagnosis, both higher and lower frequencies are reported [2, 15, 19, 23, 26]. Nuijts et al. [27] found ophthalmological abnormalities in 79% of children with newly diagnosed brain tumours and also discovered that many children had ophthalmological abnormalities when examined despite not having any ophthalmological complaints. In our study, only 38% of the children were examined by an ophthalmologist before the diagnosis. Of the children with ophthalmological tumour signs, only 53% were seen by an ophthalmologist. Therefore, the prevalence of ophthalmological tumour signs is likely higher than our results show.

Reduced visual acuity and strabismus were among the most frequent ophthalmological tumour signs (16.7% and 11.4%), but also the ophthalmological signs with the most prolonged median diagnostic interval (46 and 20.5 days), which is in agreement with other studies [15, 19]. However, reduced visual acuity and strabismus are also common ophthalmological complaints in the general paediatric population due to less severe conditions such as refractive errors and amblyopia etc. [28,29,30,31]. Consequently, common and early-onset ophthalmological tumour signs hold the potential to mimic more frequent and less severe ophthalmological disorders, which might explain the longer diagnostic interval [26]. To distinguish these tumour signs from the common differential diagnoses, factors such as sudden-onset strabismus, pupil abnormalities, and co-existing other general tumour signs should raise suspicion for intracranial pathology [9]. The RI analyses confirmed that the youngest children with strabismus as their initial tumour sign had poor chances of being diagnosed <1 month from the onset of the symptom (OR = 2.89). Only when looking at diagnoses made within one year did the RI analyses demonstrate strabismus as a symptom with low OR (OR = 0), indicating that the diagnosis had a high chance of being established within that timeframe.

Diplopia, the second-most frequent ophthalmological tumour sign (14.9%), had a shorter median time to diagnosis (14 days) than reduced visual acuity and strabismus. The RI analyses for the oldest children with diplopia as their initial tumour sign demonstrated that the symptom was associated with a quick diagnosis, indicating that this symptom is well-recognised as a potential sign of intracranial pathology. Falcone and colleagues [32] reported a higher risk of life-threatening conditions in children with diplopia and associated neurologic signs, which highlights the importance of investigating alarming patterns in children’s presenting symptoms.

Papilledema had a median diagnostic interval of 0 days, which indicates that the children are promptly scanned once the clinical finding is observed. However, how long the papilledema has been present before being diagnosed remains unknown. Papilledema was observed in 9.4% of the children. Nuijts et al. [27] found that papilledema was the most frequent ophthalmological abnormality (52%). The variance in the prevalence of papilledema in the studies may be explained by the fact that Nuijts et al. [27] examined all children after a standardised protocol performed by ophthalmologists, whereas not all children in our study underwent ophthalmological assessments. Papilledema is an important and well-known sign of increased intracranial pressure that can lead to permanent vision loss, making early detection and intervention crucial [22]. However, it requires clinical assessment to be recognised and taken together, this illustrates the importance of timely ophthalmological evaluation.

In infants and young children with open fontanelles, macrocephaly and sunset eyes can be signs of raised intracranial pressure [33, 34], and these signs also had short median diagnostic intervals (6.5 days and 1.5 days). Other tumour signs with short median diagnostic intervals included pupil abnormalities (1 day), cranial nerve palsies (3 days), nystagmus (6 days), and visual field defects (9 days). These signs share the characteristic that they have a higher predictive value for raised intracranial pressure and intracranial space-occupying lesions [7, 9, 15, 22, 35].

The occurrence of ophthalmological tumour signs at any time before diagnosis differed significantly in the age groups, with more children having ophthalmological signs in the older groups (5–11 and 12–18 years compared with <5 years). This association might be due to the ability to describe more complex symptoms, better cooperation, and biological development [2, 9, 11, 21]. The youngest children and particularly pre-verbal children cannot describe their symptoms in the same manner as older children and the tumour signs observed are only those that the parents may observe and the results of the clinical examination.

Girls had significantly more tumour signs than boys. Other studies have shown a similar trend in other CNS-related diseases in adolescents and adults [36,37,38]. However, little is known about the differences in symptomatology in children according to gender. In our study, girls also constituted a significantly higher proportion of the children with ophthalmological signs.

Overall, the median TDI was 12.6 weeks, ranking poorly compared with other studies with TDI varying from a few weeks to 2–3 months [11, 13, 19, 26, 39]. The IOS group had a longer TDI than children with other initial signs (15.9 vs 12.3 weeks), but the difference was not significant. In our study, we did not differentiate between patient delay (symptom onset to first medical consultation) and the system interval (first health care contact to diagnosis) [14]. Therefore, the longer TDI in our IOS group may be the result of a lack of awareness in both the general population and among health care professionals. Diagnostic delay may, however, be influenced by a number of other factors including socioeconomic aspects [40]. In Denmark, patients typically consult a GP before referral to an ophthalmologist or paediatric specialist, but they can also access private ophthalmologists directly, with all health care services being free of cost and covering the entire population. Despite this, socioeconomic factors play an important role in how the system is used in Denmark [41]. A campaign similar to HeadSmart (“Hjernetegn”) has been introduced in Denmark to guide and inform health care professionals how to act if specific symptoms occur, which tumour signs to be aware of, and when the child should be referred [42]. Hopefully, this initiative will help reduce system delay.

We found a higher distribution of high-grade tumours in children with ophthalmological tumour signs at any time prior to diagnosis than those without (41.1% vs 30.7%; p = 0.046). It is well-established that high-grade tumours are associated with both death and short TDI [11, 14, 15, 43, 44]. High-grade tumours grow more rapidly and aggressively, thus giving a higher risk of infiltration and compression of visual pathway structures and involvement of more anatomical sites [11, 34]. However, even when adjusting for tumour grade, we found an association between ophthalmological tumour signs before diagnosis and death for both our total population (HR: 2.11; 95% CI: 1.32–3.39; p = 0.002) and the subgroup of patients with short TDI (HR: 2.80; 95% CI: 1.25–6.29; p = 0.013). Specifically for the children with short TDI, we found that the IOS group had a higher risk of death (HR: 4.87; 95% CI: 1.41–16.83; p = 0.012), emphasising the importance of awareness of early ophthalmological tumour signs. In addition, children with a TDI between 91 and 365 days combined with ophthalmological tumour signs before diagnosis had a significantly higher risk of death in adjusted Cox regression analyses. Some studies have demonstrated an association between a TDI of 3–6 months and death [12, 43], suggesting that tumours diagnosed within an intermediate diagnostic interval could be of specific histopathologic subtypes or tumour locations, causing this link between death, ophthalmological tumour signs, and diagnostic interval. This association between ophthalmological tumour signs and an increased risk of death may be because children with ophthalmological tumour signs have tumours at a more advanced stage, where there is already growth into regions not yet affected in children without eye symptoms at the time of diagnosis.

Although short TDI is paradoxically associated with a poor prognosis, studies have also shown that reducing the diagnostic interval may improve survival and the long-term sequelae [7, 8, 12, 13, 17]. Earlier tumour detection allows initiating treatment at a less progressive stage and improves treatment options [40, 45, 46]. For a GP, a paediatrician, or an ophthalmologist, information about how the child develops, any behavioural changes, visual disturbances, and other associated potential tumour signs should be routine and will often bring crucial knowledge to the health care professional. Clinical assessment for other tumour signs that might otherwise have been left unnoticed and awareness of the number and combination of potential tumour signs are essential, and children should be referred for further evaluation at the slightest doubt to ensure faster diagnosis.

Strengths and limitations

Major strengths were the nationwide collection of high-quality data, enabling us to collect medical information from hospitals and private ophthalmologists of most children. DCCR data regarding diagnosis date, tumour grade, and location were validated in the medical files. Owing to the availability of detailed data on tumour location and previous eye history, we could distinguish tumour signs from other ophthalmological issues in most cases.

However, our methods imply a risk of including symptoms or clinical findings not caused by a brain tumour. The retrospective study design implies that only reported information from our collected files from hospitals and private ophthalmologists was available. In addition, the calculations of diagnostic intervals may be affected by recall bias. The diagnostic interval did not distinguish between patient interval and system interval and did not include socioeconomic background. This study does not analyse how specific tumour sign patterns correlate with survival status, tumour grade, or location.

Conclusion

Children with brain tumours in Denmark have a prolonged diagnostic interval, but this does not differ in children with or without ophthalmological tumour signs. Ophthalmological tumour signs are frequent and associated with a worse prognosis, emphasising the importance of timely standardised ophthalmological referral and assessment performed by ophthalmologists to reduce the diagnostic interval and improve the prognosis for children with brain tumours.

Summary

What was known before

-

Children with brain tumours often suffer from late diagnosis, impacting cure rates and risk of permanent sequelae.

-

Ophthalmological symptoms are common.

What this study adds

-

This study confirms that time to diagnosis is prolonged for children with brain tumours.

-

Ophthalmological symptoms are common and observed in more than 50% of the children included in this study.

-

Children with ophthalmological tumour signs have a higher mortality compared to those without.

-

Our findings emphasise the importance of early ophthalmological assessments in ensuring timely diagnosis of children with brain tumours.

Data availability

The majority of data generated or analysed during this study is available in this published article (and its supplementary information files). Further detailed data are not publicly available owing to individual privacy of the children included in the study.

References

Helligsoe ASL, Kenborg L, Henriksen LT, Udupi A, Hasle H, Winther JF. Incidence and survival of childhood central nervous system tumors in Denmark, 1997-2019. Cancer Med. 2022;11:245–56.

Wilne S, Collier J, Kennedy C, Koller K, Grundy R, Walker D. Presentation of childhood CNS tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:685–95.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7–30.

Kyu HH, Stein CE, Boschi Pinto C, Rakovac I, Weber MW, Dannemann Purnat T, et al. Causes of death among children aged 5–14 years in the WHO European Region: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2018;2:321–37.

Macartney G, Harrison MB, VanDenKerkhof E, Stacey D, McCarthy P. Quality of life and symptoms in pediatric brain tumor survivors: a systematic review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2014;31:65–77.

Gupta P, Jalali R. Long-term survivors of childhood brain tumors: impact on general health and quality of life. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17:99.

Wilne S, Koller K, Collier J, Kennedy C, Grundy R, Walker D. The diagnosis of brain tumours in children: A guideline to assist healthcare professionals in the assessment of children who may have a brain tumour. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:534–9.

De Ruiter MA, Van Mourik R, Schouten-Van Meeteren AYN, Grootenhuis MA, Oosterlaan J. Neurocognitive consequences of a paediatric brain tumour and its treatment: a meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:408–17.

Edmond JC. Pediatric brain tumors: the neuro-ophthalmic impact. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2012;52:95–106.

Jariyakosol S, Peragallo JH. The effects of primary brain tumors on vision and quality of life in pediatric patients. Semin Neurol. 2015;35:587–98.

Reulecke BC, Erker CG, Fiedler BJ, Niederstadt TU, Kurlemann G. Brain tumors in children: initial symptoms and their influence on the time span between symptom onset and diagnosis. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:178–83.

Barragán-Pérez EJ, Altamirano-Vergara CE, Alvarez-Amado DE, García-Beristain JC, Chico-Ponce-de-León F, González-Carranza V, et al. The role of time as a prognostic factor in pediatric brain tumors: a multivariate survival analysis. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26:2693–701.

Sadighi ZS, Curtis E, Zabrowksi J, Billups C, Gajjar A, Khan R, et al. Neurologic impairments from pediatric low-grade glioma by tumor location and timing of diagnosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65:1–8.

Shanmugavadivel D, Liu JF, Murphy L, Wilne S, Walker D. Accelerating diagnosis for childhood brain tumours: an analysis of the HeadSmart UK population data. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105:355–62.

Azizi AA, Heßler K, Leiss U, Grylli C, Chocholous M, Peyrl A, et al. From symptom to diagnosis—the prediagnostic symptomatic interval of pediatric central nervous system tumors in Austria. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;76:27–36.

Walker D, Grundy R, Kennedy C, Collier J, Wilne S, Koller K. The brain pathways guideline: a guideline to assist healthcare professionals in the assessment of children who may have a brain tumour. 2017;0–127. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/accreditation

Pogorzala M, Styczynski J, Wysocki M. Survival and prognostic factors in children with brain tumors: long-term follow-up single center study in Poland. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:323–6.

Peeler CE, Edmond JC, Hollander J, Alexander JK, Zurakowski D, Ullrich NJ, et al. Visual and ocular motor outcomes in children with posterior fossa tumors. J AAPOS [Internet]. 2017;21:375–9.

Wilne S, Collier J, Kennedy C, Jenkins A, Grout J, MacKie S, et al. Progression from first symptom to diagnosis in childhood brain tumours. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:87–93.

Dörner L, Fritsch MJ, Stark AM, Mehdorn HM. Posterior fossa tumors in children: how long does it take to establish the diagnosis?. Child’s Nerv Syst. 2007;23:887–90.

Chu TPC, Shah A, Walker D, Coleman MP. Pattern of symptoms and signs of primary intracranial tumours in children and young adults: a record linkage study. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:1115–22.

Peragallo JH. Effects of brain tumors on vision in children. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2018;58:83–95.

Nuijts MA, Stegeman I, Porro GL, Duvekot JC, van Egmond-Ebbeling MB, van der Linden DCP, et al. Ophthalmological evaluation in children presenting with a primary brain tumor. J Neuro-Ophthalmol. 2022;42:e99–e108.

Schrøder H, Rechnitzer C, Wehner PS. CLEP-99508-the-danish-childhood-cancer-registry. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:461–4.

Johnson JW, LeBreton JM. History and use of relative importance indices in organizational research. Organ Res Methods. 2004;7:238–57.

Stocco C, Pilotto C, Passone E, Nocerino A, Tosolini R, Pusiol A, et al. Presentation and symptom interval in children with central nervous system tumors. A single-center experience. Childs Nerv Syst. 2017;33:2109–16.

Nuijts MA, Stegeman I, Van Seeters T, Borst MD, Bennebroek CAM, Buis DR, et al. Ophthalmological findings in youths with a newly diagnosed brain tumor. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022;140:982–93.

Williams C, Northstone K, Howard M, Harvey I, Harrad RA, Sparrow JM. Prevalence and risk factors for common vision problems in children: data from the ALSPAC study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:959–64.

Sandfeld L, Weihrauch H, Tubæk G, Mortzos P. Ophthalmological data on 4.5- to 7-year-old Danish children. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:379–83.

Torp-Pedersen T, Boyd HA, Skotte L, Haargaard B, Wohlfahrt J, Holmes JM, et al. Strabismus incidence in a Danish population-based cohort of children. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135:1047–53.

Greenberg AE, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood esotropia. A population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:170–4.

Falcone MM, Osigian CJ, Persad PJ, Capo H, Cavuoto KM. Characteristics of diplopia in a pediatric population. J AAPOS. 2021;25:95.e1–95.e5.

Frühwald MC, Rutkowski S. Tumors of the central nervous system in children and adolescents. Dtsch Aerzteblatt Online [Internet]. 2011;108. Available from: https://www.aerzteblatt.de/10.3238/arztebl.2011.0390

Fleming AJ, Chi SN. Brain tumors in children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2012;42:80–103.

Aylward SC, Reem RE. Pediatric intracranial hypertension. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;66:32–43.

Brown DA, Elsass JA, Miller AJ, Reed LE, Reneker JC. Differences in symptom reporting between males and females at baseline and after a sports-related concussion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sport Med. 2015;45:1027–40.

Levin HS, Temkin NR, Barber J, Nelson LD, Robertson C, Brennan J, et al. Association of sex and age with mild traumatic brain injury-related symptoms: a TRACK-TBI study. JAMA Netw open. 2021;4:e213046.

Valko PO, Siddique A, Linsenmeier C, Zaugg K, Held U, Hofer S. Prevalence and predictors of fatigue in glioblastoma: a prospective study. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:274–81.

Dobrovoljac M, Hengartner H, Boltshauser E, Grotzer MA. Delay in the diagnosis of paediatric brain tumours. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:663–7.

Dang-Tan T, Franco EL. Diagnosis delays in childhood cancer: a review. Cancer. 2007;110:703–13.

Friis Abrahamsen C, Ahrensberg JM, Vedsted P. Utilisation of primary care before a childhood cancer diagnosis: do socioeconomic factors matter? A Danish nationwide population-based matched cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:1–9.

Weile KS. Opsporing af hjernetumorer hos børn og unge - Hjernetegn.dk. Hjernetegn. 2023. Available from: https://www.hjernetegn.dk/

Kukal K, Dobrovoljac M, Boltshauser E, Ammann RA, Grotzer MA. Does diagnostic delay result in decreased survival in paediatric brain tumours?. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:303–10.

Girardi F, Allemani C, Coleman MP. Worldwide trends in survival from common childhood brain tumors: a systematic review. J Glob Oncol. 2019;2019:1–25.

Ahrensberg JM, Fenger-Grøn M, Vedsted P. Primary care use before cancer diagnosis in adolescents and young adults - a nationwide register study. PLoS One. 2016;11:5–6.

Hayat MA. Pediatric Cancer. Vol. 3. Dordrecht: Springer; 2015. p. 174, 212–215.

Funding

The study was supported by donations from Engineer Otto Christensen’s Foundation, the Synoptik Foundation, Doctor Emil Sofus Friis and wife Olga Doris Friis’s Foundation. The work is part of the Danish nationwide research program Childhood Oncology Network Targeting Research, Organisation & Life expectancy (CONTROL) and supported by the Danish Cancer Society (R-257-A14720) and the Danish Childhood Cancer Foundation (2019-5934 and 2020-5769). The supporting foundations had no role in the design or conduct of this research. Open access funding provided by National Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SLVH was the designer behind the study and was in charge of data collection, interpretation of results, and revising the manuscript. JC took part in data collection, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. KS, SH and RM all took part in designing the study, interpreting the results and revising the manuscript. SK helped with data collection and revising the manuscript. VS performed statistical analyses and helped with revising the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Christiansen, J., Mathiasen, R., Heegaard, S. et al. Early ophthalmological tumour signs and diagnostic interval in children with brain tumours. Eye 39, 2245–2252 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-025-03837-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-025-03837-8

This article is cited by

-

Visual field defects in children with brain tumors

BMC Ophthalmology (2025)