Abstract

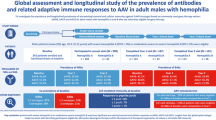

Gene therapy with AAV vectors is a promising approach for treating numerous genetic disorders but is often hindered by preexisting antibodies that neutralize the vectors. Given that females may exhibit stronger immune responses than males, this study hypothesizes that females may have higher preexisting antibody titers against AAV. Serum samples from two U.S. cohorts were analyzed for antibody titers, antibody subtypes, and transduction inhibition activity against AAV serotypes AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, AAV8, and AAV9. We found that among seropositive samples, females had higher preexisting antibody levels and neutralizing activities against AAV9 and other serotypes. Immunoglobulin subclass analysis showed IgG1 dominance in both sexes, but females had higher IgA levels, whereas males had higher levels of IgG2. We further evaluated the cellular level of this differential immune response to AAV by stimulation of male and female human PBMCs. We observed dose-dependent increase in cytokines and chemokines in female PBMCs which suggests a differential inflammatory response. Altogether, our findings suggest that the enhanced immune response in females could lead to neutralization and faster clearance of AAV vectors with potential to impact the efficacy of gene therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) mediated gene therapies represent highly promising and rapidly evolving treatments for many rare diseases [1]. It offers solutions to rare genetic disorders that historically had no cure and are common to both sexes as well as disorders that are unique to females such as Rett syndrome [2] or disproportionally associated with females such as Alzheimer and dementia [3, 4]. Despite the great progress in AAV manufacturing and AAV targeting, the efficacy of this vehicle is highly hindered by the humoral immunogenicity of AAV. High titers of preexisting antibodies against the AAV due to natural infection or previous therapies have been shown to cause clearance and neutralization of the gene delivery vector [5] and present a barrier to successful AAV therapy. These preexisting antibodies can also form immune complexes and induce antibody mediated complement activation that has been proposed to contribute to various toxicities [6, 7]. Furthermore, immune complexes can activate antigen presenting cells and accelerate the overall immune response against the gene therapy including T cell activation. In recent years, innate immunity to AAV has gained increasing attention as one of the possible triggers of immune-mediated toxicities [8]. Antibody mediated innate activation has been proposed to involve complement activation and the development of thrombotic microangiopathies [7].

Studies analyzing the impact of sex on the immune response to viral infections or vaccines show that there are sex-based differences in immune responses to pathogens and self-antigens [9]. Females have greater antibody responses to some vaccines, and typically experience more adverse reactions, in response to vaccination [10, 11]. Furthermore, females exhibit increased susceptibility to various autoimmune diseases, and males on the other hand, have preferential susceptibility to some viral, bacterial, parasitic and fungal infection (reviewed in [12]). This susceptibility in males may be attributed to their relatively lower immunological protection. The increased immune protection in females can become a double-edged sword in viral mediated gene therapy where the immune response may cause stronger and faster clearance and neutralization of the gene delivery vector.

Sex differences of the immune response to AAV gene therapy has not been investigated. The Seven AAV products that have been approved by the FDA thus far either target very young patients [13,14,15] that produce low levels of sex hormones or target x-linked disorders such as Hemophilia A, Hemophilia B and Duchenne Muscular dystrophy for which the gene therapy trials did not include females [16,17,18]. Gene therapy studies in mice show sex differences in efficacy of gene delivery; female mice had weaker transgene expression and shorter persistence of the gene which was recovered in oophorectomized mice treated with androgens [19, 20]. These studies also identified a striking difference between males and females in the level of AAV DNA in hepatocytes in immune competent and immune compromised mice, suggesting a secondary mechanism of sex differences involving AAV accessibility to the cells.

Here we evaluated the preexisting antibodies and cellular response to AAV9 and other natural AAV serotypes that are frequently utilized in gene therapy. We first focused on AAV9 because it was the first AAV vector that was approved for licensure by the US Food and Drug administration to be administered systemically [13]. We tested two cohorts of serum samples from different geographic regions within the United States and compared the binding titers, antibody subtype and transduction inhibition activity between male and female samples against various AAV serotypes that are commonly used in gene therapy. Secretome analysis of cells from males and females further suggests a differential inflammatory response between males and females.

Material and methods

Human serum samples

Ethics approval and consent to participate

For Cohort 1, fresh blood samples are collected from the NIH blood bank under a protocol approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board (CBER-047). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Serum was extracted by centrifugation of whole blood samples for 10 min at 2000 rpm at 20 oC. Serum was collected and cryopreserved in –80 oC for later use. For cohort 2, frozen sera samples were purchased from BiolVT. Age, sex and date of collection are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2.

Production of AAV vectors and sham control

AAV vectors were prepared as previously described with minor changes [21]. Briefly, AAV and sham control were made side by side by triple transfection of suspension HEK293 Viral Production Cells 2.0 with three plasmids for the capsid, for transgene and a helper plasmid. Plasmids information and sources are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Sham control underwent all the steps of AAV production and purification with a single change: cells in the sham control were treated with PBS instead of plasmids during the step of triple transfection. At 72 h post-infection, the supernatant was collected, and the cell lysate was resuspended in 10 mL lysis buffer per 2 x 108 cells. AAV vectors were released from the cells by 3 freeze thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen and 37 °C water bath followed by sonication. Unencapsidated DNA was degraded using 100 units per mL of cell lysate of Benzonase (Millipore Sigma, Billerica, MA). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation for 20 min at 10,000 × g. Finally, AAV vectors were purified using two iodixanol ultracentrifugation gradients and concentrated in 100-kDa concentration columns (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantification of AAV

Purified AAVs were subjected to quantification of the viral genome using Taqman quantitative PCR (qPCR) as well as total particles by ELISA as described below.

Quantification of viral genome

Quantification by Taqman (qPCR) was done as previously described [22] using the following primers that target the AAV-2 ITR which was identical in all AAV capsids prepared : ITR (forward: 5ʹ-CGGCCTCAGTGAGCGA-3ʹ, reverse: 5ʹ- GGAACCCCTAGTGATGGAGTT-3ʹ). The targets were amplified using SsoAdvanced Universal Probes Supermix (catalog# 1725281, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and thermocycling conditions were 3 min at 95 °C and then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s and 58 °C for 30 s on a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ Multicolor Real-Time PCR Detection System.

Quantification of total viral particles

Commercial capture ELISA kits were used to quantify the different serotypes following the manufacturer instructions (Progen Heidelburg, DE). Each Kit is made for a specific serotype and utilized a standard curve with the specific serotype (AAV1 Cat #PRAAV1 | AAV2 Cat #PRATV | AAV5 Cat3# PRAAV5 | AAV8 Cat# PRAA8 | AAV9 Cat# PRAAV9).

Human serum capture ELISA for total Ig

ELISA was used to determine preexisting antibodies to AAV serotypes AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, AAV8 and AAV9. Plates were coated overnight in 4 °C with 5 x 1010- 1x 1011 viral particles/ml (vp/ml) of the appropriate AAV in 50μL/well in half volume clear polystyrene microplates (Corning, Cat# 29442-318). Corresponding plates were coated with 1:200 dilution of sham in assay buffer (0.1% BSA in PBS-T). Next plates were washed four times with PBS-T containing 0.05% Tween20. Plates were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS-T buffer for two hours, washed and serum was added. For signal to noise assays, sera were added after a pre-dilution 1:20. For AAV9 titering assays, an initial dilution of 1:20 was followed by five or seven 1:5 dilutions. Plates were incubated at room temp for 1 h, washed and incubated with anti-human IgG antibodies conjugated with HRP at a dilution of 1:25,000 (Jackson lab, Bar Harbor, ME, Cat# 115035008) for 1 h, followed by enzymatic development (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)) (Sureblue Cat# 95059-286). Reaction was stopped by adding 35 μl of 0.667 N H2SO4.

Human Serum capture ELISA for total subclasses antibodies IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, IgM, & IgA

Coating with AAV9 and serum dilutions for all subclasses antibodies was performed in the same way as the total Ig ELISA. Detection of subclasses antibodies IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 was done using secondary and tertiary antibodies. Mouse anti human FC-isotype specific antibodies with no cross reactivity to other isotypes: IgG1 (Cat# I9388), IgG2 (Cat# I9513), IgG3 (Cat# I7260), IgG4 (Cat# I9888) (all four antibodies from Sigma, USA) were used at 1:1000 to capture the human subclasses. Tertiary HRP-labeled goat anti mouse IgA was used for detection at dilution of 1:10,000. Detection of subclasses IgA and IgM was done with HRP-labeled isotype specific antibodies (109035011 and 10903504, Jackson immune research) at dilution of 1:25,000.

Neutralization assays

HEK293 cells (Promega NC1001) and AAV9-NanoLuc® Luciferase virus (Promega) were utilized to assess neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) in human serum. Serum samples were serially diluted in PBS, then mixed with AAV9-NanoLuc, which had been diluted to a final MOI of 3,000 in viral dilution buffer (PBS + 0.1% Pluronic F68 (Gibco 24040032)). In a 50 μL reaction, 30 μL of DMEM, 10 μL diluted serum, and 10 μL of diluted AAV were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in a 96-well tissue culture plate (Corning 3917).

Frozen HEK293 cells were thawed, diluted in DMEM with 1% FBS, and seeded at 20,000 cells per well in 50 μL. The cells were plated directly onto the assay plate containing the mixture of virus and serum. The cells were then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Following incubation, extracellular NanoLuc® inhibitor (Promega N235B) and NanoLuc® live cell substrate (Promega N205B) were diluted to 5X and 25 μL of each was added to each well. Luminescence was measured using a GloMax® Discover plate reader (Promega).

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) stimulation

Human PBMCs were isolated from apheresis samples of 4 male and 4 female healthy donors under protocols approved by the National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board (CBER-047). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and informed consent was obtained from all participants. Cells were isolated using gradient-density separation with Ficoll-Hypaque (GE Healthcare) according to manufacturer instructions and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until assayed.

Cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed, washed, counted, and resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells per well in 96 well plates, in RPMI media containing 10% heat-inactivated human serum, 1% Glutamax (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 10 mM HEPES (Thermo Fisher Scientific), MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were cultured with purified AAV9 at capsid concentration of 5 x 1010 particles/ml or 1 x 1011 particles/ml for 48 h. Cells were blocked with BD GolgiPlug™ and GolgiStop (BD Bioscience) following manufacturers recommendation for the final 2–5 h of stimulation. At 48 h timepoint, cells were pelleted by centrifugation and supernatants were analyzed for protein profiling.

nELISA-based secretome analysis (NOMIC analysis)

For quantification of soluble proteins, supernatants from treated cells were frozen and sent to Nomic Bio (Montreal, Canada) for nELISA-based secretome analysis using standard protocols, as described previously [23]. Briefly, the nELISA pre-assembles antibody pairs on spectrally encoded microparticles, enabling multiplexing of multiple ELISA test in parallel. Protein concentrations on microparticles were read out by high-throughput flow cytometry (Bio-Rad ZE5 cell analyzer) and decoded using Nomic’s proprietary software. Standard curves for all targets were generated to derive pg/mL values from cytometry fluorescence units. The nELISA panel was used to quantify analytes in each sample. For the purpose of statistical analysis, when a result was below or above the known limit of detection, they received the value of the lower or higher limit of detection respectively.

Data analysis

ΔO.D was calculated by subtraction of the O.D of the background (binding to sham control plate) from the signal in the AAV coated plates. Titer was interpolated using a 4-parameter curve fit in Graphapad Prism. The cut point that represents the ΔO.D of negative samples was calculated by the sum of 3 x the standard deviation and average of all donors with negative ΔO.D values at the highest concentration. A separate cut point was established for each Ig subclass.

Transduction efficiency was calculated by normalizing sample luminescence to the negative control at corresponding dilutions using the formula:

NC50 was calculated by a 4 parameter curve fit using Graphpad Prism and interpolation of the dilution that results in 50% inhibition.

Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA and Mann–Whitney test were used. Data are shown as mean. *, ** or **** denotes p < 0.05, p < 0.01 or <p < 0.0001 respectively.

Results

Establishment of a signal to noise and titer binding anti AAV9 antibody assays

To evaluate the level of preexisting antibodies against AAV9, two quantitative methods were established: a “signal to noise” approach and a titer calculation. In the Signal to noise approach, the optical density at 450 nm (O.D) of each sample after 1:20 dilution was subtracted by the O.D of the same sample in a “sham” coated plate. Samples with ΔO.D ≥ 0 were considered seropositive. In the titer approach, each serum sample was serially diluted in AAV coated plates as well as in sham coated plates. The O.D for each sample and each dilution factor in the sham coated plates was subtracted from the O.D of the corresponding wells in the AAV coated plates. Next, ΔO.D for the titration was fitted to a 4 parameter curve fit and the dilution factor at which the ΔO.D was 0.12 was interpolated for each sample. We calculated an interpolation cut-point of ΔO.D- 0.12 by the averaging the ΔO.D of all samples deemed negative (all samples that had no change in ΔO.D after dilution) plus 3 x STDEV.

Female serum has higher levels or preexisting antibodies against AAV9 in two cohorts

To compare the level of preexisting antibodies against AAV we evaluated two cohorts of serum samples. Cohort 1 included 98 samples (61 male and 37 female) that was supplemented towards the end of the study to 120 samples (61 males and 59 females) collected by the NIH blood bank in Bethesda, MD between the years 2021–2023. Cohort 2 included 160 samples (80 male and 80 female) collected by BioIVT from multiple collection sites located in Florida, Tennessee and Pennsylvania between the years 2021 and 2022. Evaluation of two cohorts from different geographic locations decreases the chance of a geographic bias or unrepresentative sampling [24, 25].

Titer analysis of preexisting antibodies to AAV9 in cohorts 1 and 2 showed that most samples in both cohorts were seropositive with a slightly higher rate of seronegative samples in cohort 1. Seronegativity rate between males and females was not different (Fig. 1A, B), indicating that males and females encounter AAV9 at a similar rate. Interestingly, analysis of the seropositive samples in both cohorts revealed that seropositive females have significantly higher preexisting titers with a mean titer of 611 and 334 in females and 434 and 252 in males in cohorts 1 and 2 respectively (Fig. 1C, D).

Serum samples from two separate cohorts were collected in two different geographic regions and tested for presence of preexisting antibodies against AAV9. Seroprevalence and titer grouping in cohort 1 (61 male and 37 female) collected in Bethesda, MD (A) and Cohort 2 included (80 male and 80 female) collected in Florida, Tennessee, and Pennsylvania (B). Titers were divided to four groups representing negative (zero) and groups of high, medium and low ΔO.D. Cut point for high medium and low represent 25%, 50% and 75% of the highest obtained signal. Seronegative samples were excluded, and mean titer (C, D) or signal to noise analysis (E, F) are shown for cohort 1 (39 male and 20 female) (C, E) and Cohort 2 (70 male and 66 female) (D, F). * or ** denotes p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively in Mann–Whitney test.

Signal to noise analysis of the same samples revealed a similar trend in which female samples had higher ΔO.D than males with a mean ΔO.D of 1.0 and 0.69 in females and 0.64 and 0.55 in males in cohorts 1 and 2 respectively (Fig. 1E, F). Of note, the rate of seropositivity observed during the signal to noise analysis was higher than the rate of seropositivity observed in the titer analysis but showed similar trends to those observed in titer analysis. Altogether, this data indicates that female samples have higher pre-existing binding antibodies than male samples (Supplementary Figs. S1a and S1b).

Variable AAV9 specific immunoglobulin subclass patterns in male and female samples

Immune responses to AAV are typically polyclonal and consist of various immunoglobulin subclasses, with different immunological effector functions [26, 27]. We compared the relative levels of AAV9 specific antibody isotypes IgM, IgA, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 in male and female serum samples in cohort 1. Plates coated with either AAV9 or with sham control were incubated with serum samples from cohort 1 and detection was performed with HRP-conjugated IgG subclass-specific secondary antibodies. Figure 2A shows that IgG1 is the most prevalent isotype in both male and female anti AAV9 antibodies. These results are in agreement with previous work [28]. Mean IgG1 titers in females were significantly higher than male. This result of IgG1 dominance in the total preexisting titer is not surprising given the dominancy of IgG1 within the total immunoglobulins. It is likely that the increased IgG1 in females is the factor contributing to the increased titers observed in the total IgG. Interestingly, the immunoglobulin subclass distribution for subclasses that are not IgG1 was different between male and females (p < 0.0001 CHI test). The subdominant subclass in males was IgG2 and in females it was IgA (Fig. 2B). Comparison of the seropositivity of immunoglobulin subclasses is shown in Fig. 2C and shows that more females were positive to IgG1 than males. No other differences in subclass seropositivity were observed.

Specific subclass of anti AAV9 preexisting antibodies were determined by isotype specific ELISA for IgM, IgA, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 among the seropositive samples in cohort 1 (n = 36 males and 19 females). A Mean titer of each subclass. * or ** demotes p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 respectively in Mann–Whitney test. B The percent of samples with specific subclass positivity significance in CHI test <0.0001. C Relative distribution of each subclass within male and female serum samples.

Female sera have higher levels of preexisting antibodies against other natural AAV serotypes

To confirm that the increased levels of preexisting antibodies observed in females was true to other natural AAV serotypes, we manufactured AAV1, AAV2, AAV5 and AAV8 vectors and coated ELISA plates with each product. These serotypes were selected to represent distinct serotypes in AAV phylogeny that are commonly used in clinical development in their native form or with some additional capsid engineering [29,30,31,32,33]. Due to the high amount of AAV capsid required for titering assays, we used the “Signal to noise” ΔO.D approach that reduces the amount of AAV required for analysis by 6-8 fold. To provide wider sampling coverage, we supplemented cohort 1 with more female samples. Expanded cohort 1 that previously included samples from 37 females and 61 males now includes samples from 59 females and 61 males. The increased titers against AAV9 shown in Fig. 1 were repeated with the supplemented cohort as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Comparison of the mean ΔO.D for the four AAVs in the supplemented cohort 1 revealed that females have higher ΔO.D with means of 0.40, 0.56 and 0.42 in females and 0.36, 0.44 and 0.33 in males for AAV1, AAV5 and AAV8 respectively, but not for AAV2 (Fig. 3A–D). The difference between females and males were statistically significant for AAV5 and AAV8 (p = 0.006 and 0.04) and near significant for AAV1 (p = 0.14), but not for AAV2 that had comparable mean ΔO.D for male and female. This can be explained by the higher level of AAV2 seronegative female samples compared to the other serotypes (Fig. 3E). Co-prevalence of AAV specific IgG for each one of the 120 serum sample is shown in the heat map in Fig. 3E. All donors were seropositive to at least two serotype, with most donors being seropositive to three serotypes. No sex dependent co-prevalence differences were observed.

Plates were coated with various serotypes of AAV and used to test for binding of preexisting antibodies in serum from 120 human donors (61 males and 59 females). Signal to noise ratio is shown with ΔO.D. (A) AAV1, (B) AAV2, (C) AAV5 and (D) AAV8. * or ** demotes p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 respectively in Mann–Whitney test. Panel (E) shows coprevalence of the different AAV serotypes for each of the 120 samples.

Female sera have higher neutralization activity

To compare the neutralization activity of AAV9 transduction activity in male and female sera, AAV9- NanoLuc® Luciferase was incubated with serially diluted serum and added to HEK293 cells. Transduction inhibition of 30 male and 30 female samples randomly selected from cohort 2 is shown in Fig. 4A. More female samples had neutralization activity and this neutralization was apparent at higher dilutions in females. Overall, neutralization was higher in females than males (p < 0.0001 in Two-way ANOVA for sex effect). To compare the dilution factor of serum required to neutralize 50% of the AAV9-NanoLuc activity (NC50) between male and female samples, we fitted the luminescence signal to a 4 parameter curve fit for all samples in cohort 1 and 30 male and 30 female samples randomly selected from cohort 2. The NC50 results of the two cohorts were combined to increase statistical power. We found that, in agreement with the observation that females have higher total preexisting antibodies against AAV9, they also have significantly higher neutralization NC50. This indicates that the higher binding titers in females correlate to higher neutralization titers. To examine if serum from males with similar titer has different neutralization activity as female serum, we selected three samples in three groups of low medium and high titers and show the neutralization activity of male and female sera (supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, female samples had somewhat stronger neutralization activity at higher dilutions compared to male samples with similar titer.

HEK293 cells were transduced with a combination of AAV9-nanoLuc and serum from males and females at various dilutions. A NanoLuc luminescence after AAV transduction in 60 serum samples (30 males and 30 females) from cohort 2. Samples were selected randomly. B Neutralizing concentration that leads to 50% neutralization (NC50) was calculated based on a 4 parameter curve fit. 91 male and 65 female were randomly selected from cohorts 1 and 2. * demotes p < 0.05 in Mann–Whitney test.

Based on the similar observations for anti AAV9 binding titers and the AAV9 neutralizing titers, we next examines each serum sample in cohorts 1 and 2 to see if it was seropositive for binding, ΔO.D and neutralization (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 4b). We observed some correlation between the binding titers and neutralizing titers (R2 = 0.83) in which 73% of the samples were double positive to both binding and neutralization and only 2% of the samples were double negative. Five samples (5%) had a positive, albeit weak, neutralizing titer and negative binding titer. 20% of the samples had binding titers but had negative neutralization titer. This indicates that not all binding antibodies are also neutralizing. Signal to noise (ΔO.D) results had somewhat similar trend with the Nab titers, with lower correlation (R2 = 0.54). No sex dependent differences in the correlation between binding and neutralizing titers were observes. Cohort 2 had similar trends with 52% double positive samples, 13% double negative samples, 35% of the samples were positive in the ELISA assay but not in the Nab assay and no samples were found positive in the Nab assay but negative in the ELISA. The correlation between the ELISA and the Nab assay (R2 = 0.65) in cohort 2 was similar to the correlation between the signal to noise and the Nab (R2 = 0.62) (Supplementary Fig. 4a and 4c).

Serum samples from 96 donors in cohort 1 were evaluated in the two methods: anti AAV9 ELISA titer and neutralization activity after transduction with AAV9-NanoLuc. Results from ELISA are represented as interpolated titer value and results from the neutralization assay are represented as the interpolated concentration that leads to 50% neutralization (NC50). Dotted lines represent a dilution factor greater than 1.

Human PBMC from females show differential secretome pattern than male

To investigate potential sex-based differences in the response to AAV9 on a cellular level, we analyzed the secretion profiles of a selected list of chemokines and cytokines in the supernatant of stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Selection of cytokine and chemokine for evaluation was based on common secretome involved in responses to viral infection [34, 35]. PBMCs from 4 randomly selected male and female donors were stimulated with recombinant ds-GFP-AAV9 with a low and a high dose (5 x 1010 particles/ml and 1 x 1011 particles/ml; respectively), and the secretion profiles were characterized after 48 h using nELISA-based secretome.

A fold change analysis of protein secretion revealed that AAV9 stimulation induced a differential cytokine expression pattern between males and females. Females showed activation of more cytokines after stimulation with a high dose of AAV9 (Fig. 6A). IL6 and IL1β have been previously shown to increase as a result of AAV2 stimulation. Indeed, we observed a similar increase after stimulation with AAV9 [36] suggesting that AAV9 stimulation could trigger inflammatory responses regardless of the sex differences. Strikingly, we found that female samples had a stronger overall as well as relative secretion of IL6 compared to unstimulated cells than males (Fig. 6B). A similar trend was observed in IL1β, though not statistically significant, probably due to the high variability in responses across the female samples. Notably, a significant increase in GM-CSF was observed between the high dose in females and the high dose in male. Flow cytometry analysis of 3 male and 3 female PBMC samples that were used in the secretome analysis revealed that the main cells producing the IL6 were CD19 and CD3 negative cells, consisting of >80% of the gated cells (Supplementary Fig. 5), indicating that the difference in IL6 secretion between males and females are not attributed to B cells which are major antibody secreting cells. Even though we did not observe change in IL6 expression in CD19 cells after AAV activation, we further investigated the activation of specific B cell population. We expanded the cells for 7 days with AAV9 and used cellular markers for antigen secreting cells (CD3-CD19 + CD24- CD27 + CD38 + B cells) (Supplementary Fig. 6). We found that AAV9 induces a mild increase in this cell population. But the increase was not different between male and female samples.

PBMC from 4 male and 4 female donors were stimulated with AAV9 with 5 x 1010 particles/ml, 1 x 1011 particles/ml or vehicle for 48 h. Supernatant were analyzed for secretion of 8 human cytokines by multiplexed nELISA. A Fold change analysis of cytokines secretion. B Levels of individual cytokines: interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1 beta (IL-1β), IL-2, Granulocytes colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-1α, and IL-8. Data (n = 4 donors of each sex) are shown as Mean ± Standard error of the mean (SEM) on a Log 2 scale. Two-way ANOVA was performed, with * indicating p < 0.05.

A fold change analysis of chemokine secretion revealed a similar trend, that AAV9 stimulation induced a differential protein expression pattern between males and females (Fig. 7A). Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10) and CXCL9 show strong activation after AAV9 stimulation (Fig. 7B). Notably, in females, we observed a dose-dependent increase in chemokines associated with various immune cells migration and activation. Specifically, higher doses of AAV9 significantly increased the levels of Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5) (RANTES) and CCL7 (monocyte chemotactic protein3- MCP-3) in female PBMCs compared to males.

PBMC from 4 male and 4 female donors were stimulated with AAV9 with 5 x 1010 particles/ml, 1 x 1011 particles/ml or vehicle for 48 h. Supernatant were analyzed for secretion of 10 human chemokines by multiplexed nELISA. A Fold change analysis of chemokine secretion. B Levels of individual chemokines: Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10), CXCL9, CCL2, CXCL 1, CCL3, CCL7 (monocyte chemotactic protein3- MCP-3), CCL5 (RANTES), CCL4, CXCL 11 and CXCL 4 in female PBMCs compared to males. Data (n = 4 donors of each sex) are shown as Mean ± SEM on a Log 2 scale. Two-way ANOVA was performed, with * indicating p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.0005, and *** for p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Sex based differences of the immune system can impact susceptibility, and prognosis of diseases, including autoimmune diseases, infections, and cancer. The current study shows an enhanced and more neutralizing titers against various AAV serotypes in serum samples from female donors compared to male donors.

Previous studies focusing on sex differences of the immune response showed that sex and age are two major factors affecting the immune response [37]. Young females have stronger immune response than older females or young males. We did not observe any trends associated with age of the donor and the preexisting titer (Supplementary tables 1 and 2). This can be explained by the fact that we investigated evidence to past exposure to AAV and not necessarily recent exposures. AAV exposure and seroprevalence are known to increase with age [25] and therefore, the increased exposure can affect the titers and prevent from detecting any age correlations.

In this study we used two approaches to evaluate the strength of antibody binding. A “signal to noise” approach where the signal of each sample after 1:20 dilution was subtracted by the signal of the same sample in a “sham” coated plate and a titer approach in which each serum sample was serially diluted in AAV coated plates as well as in sham coated plates. The signal for each sample and each dilution factor in the sham coated plates was subtracted from the signal of the corresponding wells in the AAV coated plates. Most of the experiments were performed by both methods, with the exception of the screens for AAV serotypes other than AAV9 (Fig. 3). In those assays, the signal to noise approach was used to conserve AAV products because the titration assay requires testing each sample in multiple wells and dilutions. Using signal to noise ratio has become a potential alternative to titering assays of ADA response [38] and in some cases was shown to have a correlation to clinical outcome [39]. Indeed, our studies show some agreement between the results of the titer and signal to noise assessment (Supplementary Fig. 4) for most samples. Some samples did not have good agreement between the titer and the signal to noise approach. These samples were mostly, samples with very low to intermediate titers. It is possible that these samples had a higher signal in the “noise” wells meaning high binding to the sham controls that did not contain any AAV, which resulted in a lower ΔO.D signal but did not have such effect in the serial dilution.

Immunoglobulin subclass characterization showed that the subdominant subclass in females after IgG1 was IgA while the subdominant subclass male was IgG2 (Fig. 2B). This observation is in agreement with findings of female primates exhibiting greater IgA antibody titers to simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) which resulted in stronger ability of these females to clear infection upon challenge [40].

In this study, we examined the preexisting antibodies against five natural AAV serotypes that are commonly used in clinical development. We found a high level of cross reactivity or co- prevalence of antibodies against multiple serotypes. Interestingly, while AAV5, AAV8 and AAV9 had a disproportional higher titer in females, AAV1 and AAV2 had similar signals in males and females. It can be implied that AAV1 and AAV2 may be more appropriate for gene therapies for primarily female patients while AAV5, 8 and 9 may have lower patient qualification by females. It can also be implied that non-natural and engineered AAV vectors that have lower homology of capsid sequence and fewer common epitopes may be more effective for female patients.

Due to the observational and retrospective aspects of our study, it may be subjected to some bias. Particularly, geographic and racial bias that may be associated with the locations of the blood collection facilities [41]. In addition, samples in cohort 2 were purchased from a commercial vendor that compensated the donors for their time which may introduce socioeconomic bias [42]. Nevertheless, the increased titers in females were observed in both cohorts which reduces the concern that these population biases affected the conclusions. Other bias may be introduced by technical aspects of the experiment such as the presence of empty capsids in the preparations of the different AAV serotypes [43] or contaminants in the AAV preparation that may cause nonspecific binding in the ELISA binding assays. To reduce these technical biases, the AAV vectors used in this study were quantified using an ELISA assay that quantifies the number of vectors and not the number of viral copies. In addition, a negative control for each sample in each dilution was included by coating plates with “sham reagent” and background signal were subtracted.

Of note, many of the titers measured in our study were medium or low. While there is a consensus about the neutralizing effect of high titers, the impact of low and medium titers against the AAV has contradicting evidence. Evidences showing that in vivo neutralization can occur by titers as low as 1:5 or 1:10 have been shown in mice [44] and NHP [45]. Clinical evidence in Hemophilia patients suggested that neutralizing titers as low as 1:1 may have inhibitory impact on AAV vector transduction [46]. Low titers have been associated with decreased therapeutic efficacy when compared with patients with no evidence of pre-existing Nabs [47]. On the other hand, recent evidence using highly sensitive Nab assay suggests that low titers such as 1:5 may not induce neutralization in NHP, particularly in cases where the Nab titer does not correlate with results of binding titer [48]. Meadows et al. identified a titer of 1:400 as a the threshold for transduction interference of AAV9 in NHP [49] and Majowicz et al. found that a titer of 1:1030 did not cause interference of AAV5 in NHP. Intriguingly, the same study identified 3 human patients that were treated with AAV5 gene therapy and had acceptable efficacy, despite the fact that they had titers up to 1:340 [50]. These observations were further investigated and reported in a large clinical study with AAV5 that treated male patients with pre-existing antibodies to AAV. They found that clinical benefits and safety were observed in participants with AAV5 neutralizing antibody titers up to 1:700 [51]. A possible explanation to this apparent discrepancy may lay within the assay design. Different binding assay use different cells, AAV concentration, standards, dilution schemes and different interpolation points [52]. Furthermore, Nab assays are also sensitive to the dose, quality and purity of the AAV vector used in the assay. For example, the amount of empty capsid in the AAV used in the assay have been shown to cause variability within the same protocol [43]. Of note, most of the studies described above focused on male NHP and male patients due to the focus on Hemophilia. The clinical effect of low dose neutralizing antibodies in females is even less clear.

To further evaluate if the observed differences in titers also represent differences in the cellular level and could possibly indicate differences in the immune response to AAV gene therapy, we evaluated the effect of AAV stimulation in male and female human PBMC. We observed a dose-dependent increase in cytokines and chemokines in female PBMCs which suggests a differential inflammatory response potentially linked to sex-based differences in immune regulation. We note that donor to donor variability, though expected [53], resulted in some of the trends not showing statistically significant differences between the sexes. These differences warrant further investigation into the underlying mechanisms that may contribute to variations in immune activation and antibody response between males and females.

Conclusions and significance

The increased pre-immunity described herein may result in lower qualification of adult female patients in gene therapy clinical trials that exclude patients with preexisting antibodies to the viral vector. Alternatively, it may result in lower efficacy of the gene therapy in adult female patients in clinical trials that do not exclude patients with preexisting antibodies to the viral vector, particularly in individuals with high titers. Further studies are needed to identify the immunological basis for this sex-based differences and potentially develop mitigation strategies and to investigate the clinical significance of these sex differences.

References

Shahryari A, Saghaeian Jazi M, Mohammadi S, Razavi Nikoo H, Nazari Z, Hosseini ES, et al. Development and clinical translation of approved gene therapy products for genetic disorders. Front Genet. 2019;10:868.

Luoni M, Giannelli S, Indrigo MT, Niro A, Massimino L, Iannielli A et al. Whole brain delivery of an instability-prone Mecp2 transgene improves behavioral and molecular pathological defects in mouse models of Rett syndrome. Elife. 2020;9:e52629.

Kiyota T, Yamamoto M, Schroder B, Jacobsen MT, Swan RJ, Lambert MP, et al. AAV1/2-mediated CNS gene delivery of dominant-negative CCL2 mutant suppresses gliosis, beta-amyloidosis, and learning impairment of APP/PS1 mice. Mol Ther. 2009;17:803–9.

Hudry E, Vandenberghe LH. Therapeutic AAV gene transfer to the nervous system: a clinical reality. Neuron. 2019;101:839–62.

Smith CJ, Ross N, Kamal A, Kim KY, Kropf E, Deschatelets P, et al. Pre-existing humoral immunity and complement pathway contribute to immunogenicity of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector in human blood. Front Immunol. 2022;13:999021.

Ertl HCJ. Immunogenicity and toxicity of AAV gene therapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:975803.

Salabarria SM, Corti M, Coleman KE, Wichman MB, Berthy JA, D’Souza P et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy following systemic AAV administration is dependent on anti-capsid antibodies. J Clin Invest. 2024;134.

Costa Verdera H, Kuranda K, Mingozzi F. AAV vector immunogenicity in humans: a long journey to successful gene transfer. Mol Ther. 2020;28:723–46.

Pradhan A, Olsson PE. Sex differences in severity and mortality from COVID-19: are males more vulnerable? Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11:53.

Klein SL, Flanagan KL. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:626–38.

Scully EP, Haverfield J, Ursin RL, Tannenbaum C, Klein SL. Considering how biological sex impacts immune responses and COVID-19 outcomes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:442–7.

Forsyth KS, Jiwrajka N, Lovell CD, Toothacre NE, Anguera MC. The conneXion between sex and immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24:487–502.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Clinical Review. Onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi (Zolgensma). In. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/zolgensma 2019.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Clinical Review. delandistrogene moxeparvovec-rokl (ELEVIDYS). In. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/tissue-tissue-products/elevidys, 2023.

Therapeutics P PTC Therapeutics Announces FDA Acceptance and Priority Review of the BLA for Upstaza™. In. https://ir.ptcbio.com/news-releases/news-release-details/ptc-therapeutics-announces-fda-acceptance-and-priority-review, 2024.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Clinical Review. etranacogene dezaparvovec-drlb (Hemgenix). In. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/hemgenix, 2022.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Clinical Review. valoctocogene roxaparvovec-rvox (ROCTAVIAN). In. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/roctavian, 2023.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Clinical review, Fidanacogene elaparvovec-dzkt (BEQVEZ). In. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/beqvez, 2024.

Davidoff AM, Ng CY, Zhou J, Spence Y, Nathwani AC. Sex significantly influences transduction of murine liver by recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors through an androgen-dependent pathway. Blood. 2003;102:480–8.

Dane AP, Cunningham SC, Graf NS, Alexander IE. Sexually dimorphic patterns of episomal rAAV genome persistence in the adult mouse liver and correlation with hepatocellular proliferation. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1548–54.

Bing SJ, Justesen S, Wu WW, Sajib AM, Warrington S, Baer A, et al. Differential T cell immune responses to deamidated adeno-associated virus vector. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2022;24:255–67.

Sanmiguel J, Gao G, Vandenberghe LH. Quantitative and digital droplet-based AAV genome titration. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1950:51–83.

Dagher M, Ongo G, Robichaud N, Kong J, Rho W, Teahulos I et al. nELISA: A high-throughput, high-plex platform enables quantitative profiling of the secretome. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023.

Cao L, Ledeboer A, Pan Y, Lu Y, Meyer K. Clinical enrollment assay to detect preexisting neutralizing antibodies to AAV6 with demonstrated transgene expression in gene therapy trials. Gene Ther. 2023;30:150–9.

Klamroth R, Hayes G, Andreeva T, Gregg K, Suzuki T, Mitha IH, et al. Global seroprevalence of pre-existing immunity against AAV5 and other AAV serotypes in people with hemophilia A. Hum Gene Ther. 2022;33:432–41.

Gorovits B, Azadeh M, Buchlis G, Harrison T, Havert M, Jawa V, et al. Evaluation of the humoral response to adeno-associated virus-based gene therapy modalities using total antibody assays. AAPS J. 2021;23:108.

Long BR, Veron P, Kuranda K, Hardet R, Mitchell N, Hayes GM, et al. Early phase clinical immunogenicity of valoctocogene roxaparvovec, an AAV5-mediated gene therapy for hemophilia A. Mol Ther. 2021;29:597–610.

Boutin S, Monteilhet V, Veron P, Leborgne C, Benveniste O, Montus MF, et al. Prevalence of serum IgG and neutralizing factors against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 in the healthy population: implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:704–12.

Scott LJ. Alipogene tiparvovec: a review of its use in adults with familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency. Drugs. 2015;75:175–82.

Hoy SM. Delandistrogene moxeparvovec: first approval. Drugs. 2023;83:1323–9.

Maguire AM, Russell S, Wellman JA, Chung DC, Yu ZF, Tillman A, et al. Efficacy, safety, and durability of voretigene neparvovec-rzyl in RPE65 mutation-associated inherited retinal dystrophy: results of phase 1 and 3 trials. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:1273–85.

Sekayan T, Simmons DH, von Drygalski A. Etranacogene dezaparvovec-drlb gene therapy for patients with hemophilia B (congenital factor IX deficiency). Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2023;23:1173–84.

Dhillon S. Fidanacogene elaparvovec: first approval. Drugs. 2024;84:479–86.

Melchjorsen J, Sorensen LN, Paludan SR. Expression and function of chemokines during viral infections: from molecular mechanisms to in vivo function. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:331–43.

Mogensen TH, Paludan SR. Molecular pathways in virus-induced cytokine production. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2001;65:131–50.

Kuranda K, Jean-Alphonse P, Leborgne C, Hardet R, Collaud F, Marmier S, et al. Exposure to wild-type AAV drives distinct capsid immunity profiles in humans. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:5267–79.

Dunn SE, Perry WA, Klein SL. Mechanisms and consequences of sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024;20:37–55.

Starcevic Manning M, Kroenke MA, Lee SA, Harrison SE, Hoofring SA, Mytych DT, et al. Assay signal as an alternative to titer for assessment of magnitude of an antidrug antibody response. Bioanalysis. 2017;9:1849–58.

McCush F, Wang E, Yunis C, Schwartz P, Baltrukonis D. Anti-drug antibody magnitude and clinical relevance using signal to noise (S/N): bococizumab case study. AAPS J. 2023;25:85.

Mohanram V, Demberg T, Musich T, Tuero I, Vargas-Inchaustegui DA, Miller-Novak L, et al. B cell responses associated with vaccine-induced delayed SIVmac251 acquisition in female rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 2016;197:2316–24.

Chhabra A, Bashirians G, Petropoulos CJ, Wrin T, Paliwal Y, Henstock PV, et al. Global seroprevalence of neutralizing antibodies against adeno-associated virus serotypes used for human gene therapies. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2024;32:101273.

Khatri A, Shelke R, Guan S, Somanathan S. Higher seroprevalence of anti-adeno-associated viral vector neutralizing antibodies among racial minorities in the United States. Hum Gene Ther. 2022;33:442–50.

Earley J, Piletska E, Ronzitti G, Piletsky S. Evading and overcoming AAV neutralization in gene therapy. Trends Biotechnol. 2023;41:836–45.

Scallan CD, Jiang H, Liu T, Patarroyo-White S, Sommer JM, Zhou S, et al. Human immunoglobulin inhibits liver transduction by AAV vectors at low AAV2 neutralizing titers in SCID mice. Blood. 2006;107:1810–7.

Jiang H, Couto LB, Patarroyo-White S, Liu T, Nagy D, Vargas JA, et al. Effects of transient immunosuppression on adenoassociated, virus-mediated, liver-directed gene transfer in rhesus macaques and implications for human gene therapy. Blood. 2006;108:3321–8.

George LA, Sullivan SK, Giermasz A, Rasko JEJ, Samelson-Jones BJ, Ducore J, et al. Hemophilia B gene therapy with a high-specific-activity factor IX variant. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2215–27.

Manno CS, Pierce GF, Arruda VR, Glader B, Ragni M, Rasko JJ, et al. Successful transduction of liver in hemophilia by AAV-Factor IX and limitations imposed by the host immune response. Nat Med. 2006;12:342–7.

Long BR, Sandza K, Holcomb J, Crockett L, Hayes GM, Arens J, et al. The impact of pre-existing immunity on the non-clinical pharmacodynamics of AAV5-based gene therapy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019;13:440–52.

Meadows AS, Pineda RJ, Goodchild L, Bobo TA, Fu H. Threshold for pre-existing antibody levels limiting transduction efficiency of systemic rAAV9 gene delivery: relevance for translation. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019;13:453–62.

Majowicz A, Nijmeijer B, Lampen MH, Spronck L, de Haan M, Petry H, et al. Therapeutic hFIX activity achieved after single AAV5-hFIX treatment in hemophilia B patients and NHPs with pre-existing anti-AAV5 NABs. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2019;14:27–36.

Pipe SW, Leebeek FWG, Recht M, Key NS, Castaman G, Miesbach W, et al. Gene Therapy with etranacogene dezaparvovec for hemophilia B. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:706–18.

Gorovits B, Fiscella M, Havert M, Koren E, Long B, Milton M, et al. Recommendations for the development of cell-based anti-viral vector neutralizing antibody assays. AAPS J. 2020;22:24.

Longo DM, Louie B, Wang E, Pos Z, Marincola FM, Hawtin RE, et al. Inter-donor variation in cell subset specific immune signaling responses in healthy individuals. Am J Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;1:1–11.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Abdul Mohin Sajib and Dr. Alan Baer for training and advice on AAV manufacturing and Dr. Fei Mo and Dr. Ross Marklein for helpful review of the manuscript draft.

Funding

This work was supported by the FDA Office of Women’s Health. This project was supported in part by an appointment to the ORISE Research Participation Program at the CBER, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and FDA/Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: SW, RM, LA. Methodology: SW, TH, MS, LA, SB, SH, SS, JNP Supervision: RM. Writing (original draft): SE, LA, RM. Writing (review and editing): TH, MS, SB.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warrington, S., Hoang, T.T., Seirup, M. et al. Unveiling the sex bias: higher preexisting and neutralizing titers against AAV in females and implications for gene therapy. Gene Ther 32, 339–348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-025-00528-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41434-025-00528-7