Abstract

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and arterial stiffness are closely related and may behave reciprocally as cause or effect, interacting in a vicious cycle. Both SBP and arterial stiffness increase with age in populations in most developed countries. However, the age-related increase in SBP appears to be absent in indigenous populations, partially because of their lifelong low-sodium and high-potassium diets, whereas age-related arterial stiffening in these populations remains to be determined. We performed a field survey of the indigenous population of Soroba, a small village located in the central highlands of Papua, Indonesia. Blood pressure levels and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) were measured using an automatic device. A total of 125 native Papuans 16–75 years of age (59% women) were included in this study. SBP and pulse pressure were not correlated with age. However, diastolic and mean arterial pressure levels increased with age. The prevalence of hypertension was 5% (n = 6; all women), and baPWV significantly increased with age. Compared with participants 45 years of age and older, those younger than 45 years had a higher body mass index (BMI) and spot urine sodium-to-potassium ratio but lower baPWV; however, SBP was not different between these age groups. Multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that SBP was independently associated with baPWV, sex and BMI but not with age; baPWV was independently associated with SBP, age, BMI, sex and heart rate. SBP and baPWV were closely related, but the age-related changes in these measurements differed in this highland Papuan population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) increases with age in most developed countries, and hypertension is a major global health problem [1]. Hypertension affects more than 40% of the world’s population 25 years of age and older and approximately 80% of people 75 years of age and older, and it is considered to be a leading cause of death, stroke, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and chronic renal failure. Arterial stiffening, which is associated with pulse wave velocity (PWV), is also an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events, even after adjusting for blood pressure, age, and other known risk factors [2]. Both SBP and arterial stiffness increase in parallel with age in most developed countries, and they are often thought to be an inevitable part of the aging process [3, 4]. Blood pressure is transmitted into the arterial wall, where it promotes progressive degeneration resulting in a progressively stiffer artery [5]. The aorta and large arteries become progressively less distensible, and the ability to absorb pulsations from the ejecting ventricle is reduced with advancing age. Therefore, SBP and arterial stiffness are closely related and may behave reciprocally as cause or effect, interacting in a vicious cycle. Several studies have found that aortic PWV was an independent predictor of a longitudinal increase in SBP and incident hypertension [6, 7], suggesting that the age-related increase in arterial stiffness has a causative effect on the age-related SBP increase. However, the relationship between SBP and arterial stiffness is more complicated. Recent studies have reported that higher SBP was associated with a greater rate of increase in aortic PWV over time [8].

SBP is positively associated with sodium excretion and urine sodium-to-potassium (Na/K) excretion ratio, and it is inversely associated with potassium excretion [9, 10]. Arterial stiffness is also positively associated with sodium excretion [11,12,13], and it is inversely associated with potassium excretion [14]. An understanding of the interactions among these factors—aging, blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and diet (sodium and potassium)—is a major public health priority.

The international study of salt and blood pressure showed that four remote populations—the Yanomami and Xingu Indians of Brazil and rural populations in Kenya and Papua New Guinea—had the lowest average blood pressure levels among all populations included in the study, as well as little or no age-related increase in blood pressure, likely because of their low salt intake (<3 g/day) and/or high consumption of vegetables [15]. Arterial stiffness in these indigenous populations has not yet been examined.

We have recently reported that SBP did not increase with age in 100 native Papuans 30 years of age or older [16]. This study aimed to investigate the age-related changes in arterial stiffness and blood pressure levels among indigenous Papuan highland people.

Methods

Subjects

In 2014, as part of health promotion activities, we performed a field survey of the indigenous population of Soroba, a small village located in the central highlands of Papua, situated at an altitude of 1600 m, approximately 10 km from the city of Wamena, Republic of Indonesia. Most villagers maintain a traditional lifestyle, even today. There is no running water. Sweet and taro potatoes are their staple food; however, their lifestyle is changing, including food use. Alcohol consumption is prohibited by the government, and no villagers take any regular medications.

The village leader agreed to participate in the survey, the purpose of which was explained to all villagers. All subjects volunteered to participate after the announcement of the availability of medical checkups. A total of 129 native Papuans 15 to 75 years old, 59% of whom were women, were included in this study. The studies were of healthy volunteers. All participants except for one agreed to undergo measurements of brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) and ankle-brachial index (ABI). A 15-year-old male was diagnosed with sequelae of encephalitis by a local doctor and was excluded from this analysis. Consent forms were fingerprinted by non-literate participants. The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the University of the Ryukyus.

Indonesian collaborators and those co-authors who spoke both English and Indonesian, local people who spoke both Indonesian and the local language of Soroba village, and co-author E.G., who spoke English, Indonesian and Japanese, served as interpreters. The ages of 12 participants were established by checking their Indonesian identity cards (the Kartu Tanda Penduduk). However, the other participants did not know their exact ages; the criteria for estimating age were physical appearance, number and age of children, personal knowledge of the interpreters, and calendars of local events.

ABI and baPWV measurements

ABI and baPWV were measured using a validated automatic device (BP-203RPE, III form PWV/ABI: Omron-Colin Co., Tokyo, Japan), which simultaneously measured pulse volume in the brachial and ankle arteries using an oscillometric method, together with bilateral arm and ankle blood pressure [17]. Both ABI and baPWV were measured at rest in the supine position for at least 5 min. All measurements were performed by the same person (A.I.). Hypertension was defined as supine SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg recorded with subjects in the supine position for at least 5 min. Pulse pressure (PP) was calculated as SBP—DBP. As severe atherosclerotic arterial stenosis affects the recording and accuracy of baPWV, a 65-year-old woman with an ABI of 0.89 was excluded from this analysis.

Spot urine salt concentration and Na/K ratio

Semi-quantitative spot urine salt concentration was estimated using salt titration tape (Eiken, Tochigi, Japan) [18]. The salt titration tape was dipped in urine, and the chloride concentration was read directly from the strip 1 min later, according to the red-to-yellow color change. Spot urine Na/K ratio was measured using a handy-sized urinary Na/K ratio monitor (HEU-001F, Omron healthcare, Kyoto, Japan).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, or as percentages for categorical variables. Two-sided tests with significance levels <0.05 were used. The means and medians were compared using Student’s t test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, respectively. Proportions were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Univariate regression and correlation analyses were used to analyze the relations between variables of interest. Multiple regression analyses were performed to determine independent predictors of SBP and baPWV. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP (version 8.0.2).

Results

Characteristics

The average ages were 38 and 43 years for women and men, respectively (Table 1). Women represented 59% of observations. Compared with men, women were shorter and had lower body mass indexs (BMIs). BMI was negatively associated with age (Table 2). Participants 45 years of age and older had a higher prevalence of underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2) than those younger than 45 years (41% vs. 7%, p < 0.001). Women had a higher prevalence of underweight than men (28% vs. 4%, p < 0.001). The prevalence of overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2) was 5% and 12% for women and men, respectively (p = 0.316), and only one man was obese (BMI 33 kg/m2).

Spot urine salt concentration and Na/K ratio

Spot urine Na/K ratio was positively correlated with spot urine salt concentration (Fig. 1). Urine salt concentrations of ≤ 4 g/L were more common in participants 45 years of age and older than in those younger than 45 years (28% vs. 4%, p < 0.001). The urine Na/K ratio was inversely associated with age (r2 = 0.09, p < 0.001) (Table 2), and participants 45 years of age and older had a significantly lower mean urine Na/K ratio than those younger than 45 years old (1.00 ± 1.01 vs. 1.80 ± 1.44, p = 0.002).

Blood pressure, prevalence of hypertension, and baPWV

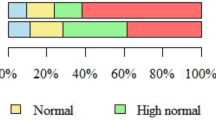

Compared with men, women had a higher heart rate, DBP, and MAP (Table 1). The prevalence of hypertension was 5%, representing six individuals, all of whom were women. Isolated systolic and diastolic hypertension accounted for 4 (3%) and 1 (1%), respectively. SBP, PP, and baPWV did not differ between women and men. The age-adjusted analysis, however, revealed that SBP (p = 0.024), DBP (p = 0.001), and MAP (p < 0.001) were higher in women than in men, whereas PP (p = 0.839) and baPWV (p = 0.693) did not differ between women and men.

Age-related change in blood pressure and baPWV

Overall, no significant correlation between SBP and age was observed (Table 2; Fig. 2a). Linear regression analysis showed that DBP and MAP increased with age, whereas PP and heart rate did not change significantly with age (Table 2, Fig. 2b–e). baPWV was positively correlated with age (Table 2, Fig. 2f). Compared with participants younger than 45 years, those 45 years and older had higher MAP and DBP, even after adjusting for sex, BMI, and heart rate. Neither SBP, PP nor heart rate differed between participants younger than 45 years and 45 years and older (Table 1). baPWV was significantly higher in participants 45 years and older than those younger than 45 years, even after adjusting for SBP, sex, BMI, and heart rate.

Determinants of SBP, DBP, and baPWV

Univariate analyses showed that SBP was positively correlated with baPWV but not with age (Table 3). Multiple regression analysis revealed that baPWV, sex, and BMI were independent determinants of SBP, accounting for 40% of the variability of SBP in this population. DBP was positively associated with SBP, baPWV, heart rate, and age, and it was inversely correlated with BMI. Multiple regression analysis revealed that baPWV, heart rate, and sex were independent determinants of DBP. Univariate analyses demonstrated that baPWV was positively correlated with age, SBP, and heart rate, and it was inversely correlated with BMI. Multiple regression analysis revealed that SBP, age, BMI, sex, and heart rate were independent predictors of baPWV, accounting for 60% of its variability. Spot urine Na/K was not associated with SBP and baPWV.

Discussion

This study showed that even today, there is still no significant age-related increase in SBP and PP in indigenous highland Papuan populations. In contrast, baPWV, MAP, and DBP increased with age, and there was also an age-related decrease in BMI, spot urine salt concentration, and Na/K ratio. The results of this study indicate that an SBP increase may not always precede arterial stiffening or that a traditional lifestyle, particularly a traditional dietary habit, may attenuate arterial stiffness-induced increases in SBP. The results of this study also indicate that sodium restriction and/or higher potassium intake could prevent an age-related increase in SBP but possibly not in arterial stiffening.

Previous epidemiological studies showed that SBP and arterial stiffness increase in parallel with age, interacting with each other and resulting in a vicious cycle [3, 4]; therefore, it is still unclear whether arterial stiffness is a cause of hypertension or an effect. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging showed that PWV was an independent predictor of the longitudinal increase in SBP and of incident hypertension in community-dwelling populations followed up for over 4 years [6]. The Framingham Heart Study showed that PWV at baseline was associated with SBP at follow-up; however, the opposite was not true, as SBP at baseline was not associated with PWV at follow-up [7]. These studies indicate that arterial stiffening is not simply a result of hypertension; rather, when it is accelerated, arterial stiffening is an underlying pathophysiological cause of the increase in blood pressure. In this study of indigenous Papuan populations, however, we found a dissociation in the age-related change of SBP and PWV with advancing age, similar to the results of another recent longitudinal study [19]. PWV increased with advancing age, despite a decrease in SBP with age over 60 years in men. The authors speculated that the age-related aortic dilatation may affect the dissociation of the PWV and SBP trajectories. In animal experiments, an increase in PWV that occurs independently of blood pressure change has been reported [20, 21]. Further studies are needed to understand the age-related relationship between PWV and SBP.

Sex and baPWV were associated with both SBP and DBP; however, BMI was only associated with SBP, and heart rate was only associated with DBP. The different effects of BMI and heart rate on SBP and DBP are unclear from this study.

Coupling and cross-talk between small and large artery changes are attributable to hypertension [22]. Structural alterations of small arteries increase total peripheral resistance, and DBP/MAP may in turn increase large artery stiffness through the loading of stiff components of the arterial wall at high blood pressure levels; finally, the increased large artery stiffness may be a primary determinant of the increased SBP/PP, which, in turn, damages small arteries in target organs. In conjunction with these findings, baPWV was positively associated with both SBP and DBP.

The Framingham Study has shown that changes in blood pressure are linked with age [23]. During early adult life, an age-related increase in peripheral vascular resistance predominates over an increase in large artery stiffness, causing the increase in DBP with age to be greater than the increase in SBP; consequently, PP decreases with age [24]. Concordant with these findings, an age-related increase in MAP and DBP but not in SBP and PP was observed in this study. These results indicate that structural alteration of small resistance arteries and arterial stiffness are precursors rather than consequences of elevated SBP.

SBP increases with age in most developed countries. The INTERSALT study, however, revealed that four indigenous populations had a low-sodium diet (0.004–1.18 g/day) and a low urine Na/K ratio (<0.01–1.78) but had little or no hypertension or increase in blood pressure with age [15]. Exact urine sodium and potassium concentrations were not measured in this study; however, the spot urine Na/K ratio was low, particularly in participants 45 years of age and older, such as the value of remote INTERSALT populations. We performed a nutrition assessment using a 24-hour recall method in six women 30–39 years of age and two men 50–59 years of age, and we found that the average sodium and potassium intakes were 816 mg/day and 6165 mg/day, respectively. These results indicate that although the lifestyle is changing in Papuan populations, particularly in populations younger than 45 years of age, they still maintain a low-sodium and high-potassium diet compared to inhabitants of developed countries. Several studies have shown that the 24-h collected and spot urine Na/K ratios were positively associated with SBP [9, 10, 25]. However, the association between estimated sodium excretion and SBP was small in subjects consuming a lower-sodium diet (3–5 g/day) and was not significant in those with the lowest-sodium diet (<3 g/day) [10]. Concordant with these results, the spot urine Na/K ratio was not associated with SBP in this study.

Although sodium balance and blockade of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system are important factors in preventing arterial stiffening, potential adverse effect of extreme sodium depletion on the arterial stiffening and cardiovascular events has been reported [26, 27]. A cross-sectional study has shown that the relationship between sodium intake and carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (cfPWV) resembles a J-shaped curve [26]. Further studies are needed to identify an adequate level of sodium and potassium intake to lower the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (i.e., the bottom of the J-curve for the arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events).

In this study, women had higher blood pressure levels and heart rates compared with men, despite having lower BMIs. These results suggest that higher blood pressure in women might be caused by sympathetic overactivity. However, SBP and DBP levels were higher in women than in men, even after adjusting for heart rate, indicating that other factors, except for heart rate, might be present in the difference of blood pressure by sex.

Obesity is one of the greatest public health concerns worldwide. Social globalization influences lifestyle changes, particularly dietary habit, in younger Papuan populations, resulting in an increase in body weight. In this study, BMI was negatively associated with age and was significantly lower in participants 45 years of age and older than those younger than 45 years of age. Multiple regression analysis showed that BMI was positively associated with SBP, indicating that an age-related increase in SBP might be partly prevented by a reduction in body weight. A previous study has reported that BMI is positively and linearly associated with both SBP and DBP [28]. The different effects of BMI on SBP and DBP in this study are uncertain. The relationship between obesity and arterial stiffness remains controversial [29, 30]. In most previous studies from developed countries, the average BMI was over 25 kg/m2. The average BMI of the Papuan population was 22 kg/m2 in men and 20 kg/m2 in women, and BMI was inversely correlated with baPWV before and after adjusting for covariates. This finding is compatible with a recent study that showed a U-shaped association between BMI and aortic PWV in young Swedish adults [31].

The primary strength of this study is that the effects of medicines, particularly antihypertensive drugs, on blood pressure and urine sodium and potassium excretion were completely excluded. The study had a small sample size and a cross-sectional design; thus, it cannot establish longitudinal relationships among sodium and potassium intake and blood pressure and arterial stiffness. We were not able to confirm all participants’ exact ages from national identity cards, which is the major limitation of this study. However, the values of BMI, spot urine Na/K excretion ratio, and baPWV provided reasonable results. We evaluated the Na/K excretion ratio from spot urine specimens, and we estimated urine sodium excretion concentration using salt titration tape. Although the quantitativity and reliability of these methods to estimate 24-hour urinary sodium and potassium excretions are low and actual measurement of 24-hour urine sodium and potassium excretion would be ideal, such an approach was impractical for this region. We used baPWV instead of cfPWV, the gold standard index of large arterial stiffness; however, we can simultaneously measure bilateral arm and ankle blood pressure with this apparatus. baPWV reflects the stiffness in large- to middle-sized arteries. A strong positive association between baPWV and cfPWV (r = 0.76) has been previously reported [32]. cfPWV is the primary independent correlate of baPWV, explaining 58% of the total variance in baPWV, whereas an additional 23% of the variance was explained by femoral-ankle PWV. In contrast with the exponential increase in aortic (elastic artery) PWV with age, peripheral muscular arterial PWV increases much more gradually or may even decrease with age [33]. This finding suggests that the age-related increase in baPWV was largely attributable to aortic stiffness in older age. Further studies are needed to demonstrate the large arterial PWV in Papuan populations.

The present study provides the first evidence that an age-related increase in baPWV is not necessarily associated with an age-related increase in SBP in indigenous Papuan populations who maintain traditional lifestyles even today. Lifelong dietary habits may affect the differences in the age-related changes of SBP and baPWV.

References

Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–223.

Vlachopoulos C, Xaplanteris P, Aboyans V, Brodmann M, Cífková R, Cosentino F et al. The role of vascular biomarkers for primary and secondary prevention. A position paper from the European society of cardiology working group on peripheral circulation. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:507–532.

McEniery CM, Wilkinson IB. The pressures of aging. Hypertension. 2013;62:823–824.

O’Rourke MF, Hashimoto J. Mechanical factors in arterial aging: a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1–13.

AlGhatrif M, Lakatta EG. The conundrum of arterial stiffness, elevated blood pressure, and aging. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17:523

Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Shetty V, Wright JG, Muller DC, Fleg JL et al. Pulse wave velocity is an independent predictor of the longitudinal increase in systolic blood pressure and of incident hypertension in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1377–1383.

Kaess BM, Rong J, Larson MG, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, Levy D et al. Aortic stiffness, blood pressure progression, and incident hypertension. JAMA. 2012;308:875–881.

AlGhatrif M, Strait JB, Morrell CH, Canepa M, Wright J, Elango P et al. Longitudinal trajectories of arterial stiffness and the role of blood pressure: The Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Hypertension. 2013;62:934–941.

Intersalt. Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood. BMJ. 1988;297:319–328.

Mente A, O’Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Poirier P, Wielgosz A et al. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:601–611.

Avolio A, Deng FQ, Li WQ, Luo YF, Huang ZD, Xing LF et al. Effects of aging on arterial distensibility in populations with high and low prevalence of hypertension: comparison between urban and rural communities in China. Circulation. 1985;71:202–210.

Safar ME, Temmar M, Kakou A, Lacolley P, Thornton SN. Sodium intake and vascular stiffness in hypertension. Hypertension. 2009;54:203–209.

Han W, Han X, Sun N, Chen Y, Jiang S, Li M. Relationships between urinary electrolytes excretion and central hemodynamics, and arterial stiffness in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2017;40:746–751.

Dart AM, Qi QiXL. Determinants of arterial stiffness in Chinese migrants to Australia. Atherosclerosis. 1995;117:263–272.

Carvalho JJ, Baruzzi RG, Howard PF, Poulter N, Alpers MP, Franco LJ et al. Blood pressure in four remote populations in the INTERSALT Study. Hypertension. 1989;14:238–246.

Fujisawa M, Ishimoto Y, Chen W, Ida I, Manuaba B, Garcia E et al. Correlation of systolic blood pressure with age and body mass index in native Papuan populations. Hypertens Res. 2012;35:1–2.

Ishida A, Miyagi M, Kinjo K, Ohya Y. Age- and sex-related effects on ankle-brachial index in a screened cohort of Japanese: the Okinawa peripheral arterial disease study (OPADS). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:712–718.

Tochikubo O, Sasaki O, Umemura S, Kaneko Y. Management of hypertension in high school students by using new salt titrator tape. Hypertension. 1986;8:1164–1171.

Scuteri A, Morrell CH, Orrù M, Strait JB, Tarasov KV, Ferreli LAP et al. Longitudinal perspective on the conundrum of central arterial stiffness, blood pressure, and aging. Hypertension. 2014;64:1219–1227.

De Marco VG, Habibi J, Jia G, Aroor AR, Ramirez-Perez FI, Martinez-Lemus LA et al. Low-dose mineralocorticoid receptor blockade prevents western diet-induced arterial stiffening in female mice. Hypertension. 2015;66:99–107.

Mattison JA, Wang M, Bernier M, Zhang J, Park S-SS, Maudsley S et al. Resveratrol prevents high fat/sucrose diet-induced central arterial wall inflammation and stiffening in nonhuman primates. Cell Metab. 2014;20:183–190.

Laurent S, Boutouyrie P. The structural factor of hypertension: large and small artery alterations. Circ Res. 2015;116:1007–1021.

Franklin SS, Gustin W, Wong ND, Larson MG, Weber MA, Kannel WB et al. Hemodynamic patterns of age-related changes in blood pressure. The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1997;96:308–315.

Vlachopoulos C, O’Rourke M. Diastolic pressure, systolic pressure, or pulse pressure? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2000;2:271–279.

Tabara Y, Takahashi Y, Kumagai K, Setoh K, Kawaguchi T, Takahashi M et al. Descriptive epidemiology of spot urine sodium-to-potassium ratio clarified close relationship with blood pressure level: the Nagahama study. J Hypertens. 2015;33:2407–2413.

García-Ortiz L, Recio-Rodríguez JI, Rodríguez-Sánchez E, Patino-Alonso MC, Agudo-Conde C, Rodríguez-Martín C et al. Sodium and potassium intake present a J-shaped relationship with arterial stiffness and carotid intima-media thickness. Atherosclerosis. 2012;225:497–503.

O’Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Wang X, Liu L et al. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:612–623.

Whilock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J. et al.Prospective Studies Collaboration. Body mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1083–1096.

Wildman RP, Mackey RH, Bostom A, Thompson T, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Measures of obesity are associated with vascular stiffness in young and older adults. Hypertension. 2003;42:468–473.

Rodrigues SL, Baldo MP, Lani L, Nogueira L, Mill JG, Sa Cunha R. De. Body mass index is not independently associated with increased aortic stiffness in a Brazilian population. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:1064–1069.

Fernberg U, Fernström M, Hurtig-Wennlöf A. Arterial stiffness is associated to cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index in young Swedish adults: the lifestyle, biomarkers, and atherosclerosis study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24:1809–1818.

Munakata M, Ito N, Nunokawa T, Yoshinaga K. Utility of automated brachial ankle pulse wave velocity measurements in hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:653–657.

Mitchell GF. Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: implications for end-organ damage. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1652–1660.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS, 21256005, 25257507) to K.O. We thank all villagers who volunteered for the survey. We thank Ms. Chihiro Ebashi and Mr. Daiji Yoshimoto at Kouchi University and Mr. Morihiro Ohta at the University of the Ryukyus for their contributions to this survey. Andre Liem and Herry Wondiwoy at the Papua Tour Guides Community provided logistical and language assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ishida, A., Fujisawa, M., del Saz, E.G. et al. Arterial stiffness, not systolic blood pressure, increases with age in native Papuan populations. Hypertens Res 41, 539–546 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0047-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0047-z

This article is cited by

-

Serum soluble (pro)renin receptor level as a prognostic factor in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Exploring and comparing definitions of healthy vascular ageing in the population: characteristics and prospective cardiovascular risk

Journal of Human Hypertension (2021)

-

Characteristics of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability in hemodialysis patients

Hypertension Research (2019)