Abstract

Red cell distribution width (RDW), a measure of variation in red blood cell size, is routinely reported in the results of a complete blood count. Recent studies have found that RDW is a predictor of high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, previous cross-sectional studies have shown a possible association between high RDW and hypertension. However, the longitudinal relationship between high RDW and incident hypertension is uncertain. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between RDW and the development of hypertension. In this retrospective cohort study, we analyzed 124,261 participants without hypertension at baseline who underwent two health checkups at 4-year intervals from 2005 to 2016. The subjects were divided into quartiles (Q1–Q4) according to their baseline RDW levels. Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the OR and 95% CI for the development of hypertension after 4 years. After 4 years, 6827 cases (5.5%) of incident hypertension were observed. The incidence rates of hypertension were 4.66%, 5.66%, 5.99%, and 5.46% for Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 of RDW, respectively. The ORs (95% CIs) for incident hypertension compared with Q1 were 1.19 (1.10–1.29), 1.28 (1.18–1.39), and 1.32 (1.22–1.44) for Q2, Q3, and Q4 of RDW, respectively. High RDW was significantly and independently associated with the development of hypertension in Korean adults. Further research is warranted to verify the mechanism underlying this relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Red cell distribution width (RDW), a measurement of the variation in red blood cell size, is reported in a routine complete blood count (CBC) [1]. A higher RDW indicates greater variation in size. The normal reference range of RDW in humans is 11.5–14.5%. Traditionally, RDW in association with mean corpuscular volume (MCV) has been used to identify specific anemias, such as iron deficiency, sickle cell disease, myelodysplasia, and chronic liver disease [2].

Studies on the clinical efficacy of RDW in areas other than hematology have suggested the possibility of using RDW as a risk-prediction tool, as it is inexpensive and easy to measure. RDW is a predictor of high mortality, not only in cases of cardiovascular, lung, liver, and kidney diseases but also in the general population [3]. Furthermore, this factor is a predictor of the incidence and progression of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease [4].

Hypertension is an important risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and chronic kidney disease [5]. This condition is the leading cause of global disease burden and the most important cause of death worldwide [5,6,7]. Because hypertension is preventable and reversible, it is important to understand the risk factors and pathophysiology of hypertension.

Previous small cross-sectional studies have suggested an association between RDW and hypertension [8, 9]. However, this association is uncertain, and few longitudinal studies have been conducted on the relationship between RDW and hypertension. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between RDW and the development of hypertension. We analyzed participants in a health checkup program at a tertiary hospital in Korea.

Methods

Study population

The Kangbuk Samsung Health Study consisted of participants who received a comprehensive health examination at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital Health Screening Centers in Seoul and Suwon, South Korea. The 138,912 people who underwent two health checkups at 4-year intervals from January 2005 to December 2016 were considered potential study subjects. For those who had several health checkups, the data from the last examination were used. We excluded 702 records due to missing variables of interest. We also excluded 13,949 subjects with hypertension at baseline, leaving 124,261 participants for the study (Fig. 1). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, and the requirement for informed consent was waived because personal information was removed prior to accession.

Measurements

The health checkup consisted of anthropometric measurements, biochemistry studies, and a self-administered questionnaire on medical history, medication use, and health-related behavior. Anthropometric data were collected by standardized protocols and trained staff. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2).

Blood pressure (BP) was measured three times by trained nurses while the subjects were seated with the arm supported at heart level, and the three readings were averaged to obtain systolic BP and diastolic BP. We used a standard mercury sphygmomanometer (from 2005 to 2011) and automated oscillometric devices (53000-E2, Welch Allyn, NY, USA; from 2012 to 2016) to measure BP. Hypertension was defined as high BP (systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg) or the current use of antihypertensive medication.

Hemoglobin, MCV, and RDW were measured with the Sysmex XE-2100D Automated Hematology Analysis System (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan) and Advia 2120 (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, New York, NY, USA). Serum glucose, total cholesterol, and uric acid levels were determined using an enzymatic colorimetric assay. Serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) was determined with a particle-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay on a Modular Analytics P800 apparatus (Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan). Serum insulin was measured with an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on a Modular Analytics E170 apparatus (Roche Diagnostics). We calculated the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation [10].

Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dL, a history of diabetes, or the use of medication for diabetes. Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol >240 mg/dL or a history of dyslipidemia. The Laboratory Medicine Department at Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul, Korea has been accredited by the Korean Society of Laboratory Medicine and the Korean Association of Quality Assurance for Clinical Laboratories. The laboratory participates in the College of American Pathologists Survey/Proficiency Testing program.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. The participants were divided into quartiles according to baseline RDW (Q1–Q4).

A comparison of the subjects according to RDW quartiles was performed using one-way analysis of variance, Kruskal–Wallis H, and chi-square tests. Logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between RDW quartile and incident hypertension at follow-up. Covariates in multivariate logistic regression were age, sex, BMI, systolic BP, diabetes, dyslipidemia, eGFR, hsCRP, hemoglobin, MCV, current smoker, alcohol intake, and regular exercise. To test for linear trends according to RDW quartile, category numbers were used as a continuous variable and tested their statistical significance in the regression model. To test the improvement of the hypertension prediction model by adding RDW, C-statistics were compared (roccomp command in Stata). In addition, we performed subgroup analyses stratified by age (<40 vs. ≥40 years), sex (female vs. male), BMI (<23.5 vs. ≥23.5 kg/m2), diabetes (non-DM vs. DM), smoking status (never/former smoker vs. current smoker), alcohol intake (<10 vs. ≥10 g/day), regular vigorous exercise (<2 vs. ≥2 times per week) and hsCRP (<0.02 vs. ≥0.02 mg/L).

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Reported P values were two-tailed, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 124,261 participants were enrolled in this study. The participants were classified into RDW quartiles as follows: Q1 (≤12.2), Q2 (12.3–12.6), Q3 (12.7–13.0) and Q4 (≥13.1). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants according to RDW quartiles. The mean age of the participants was 37.0 ± 6.3 years, and the proportion of males was 55.9%. As the RDW increased, the age increased and the proportion of men decreased. The mean systolic and diastolic BP were 108 ± 11 mmHg and 69 ± 8 mmHg, respectively. The systolic and diastolic BP decreased as the RDW increased. As the RDW increased, Hb, MCV, and ferritin decreased and total iron-binding capacity increased.

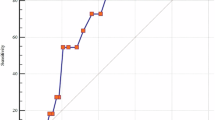

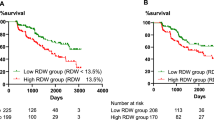

After 4 years, 6827 (5.5%) cases of incident hypertension were observed. The incidence rates of hypertension were 4.66%, 5.66%, 5.99%, and 5.46% for Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4 of RDW, respectively. Systolic and diastolic BP changes and the numbers of new patients on hypertension medication after 4 years increased as the levels of baseline RDW increased (Fig. 2).

Table 2 shows the association between RDW and incident hypertension. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, the OR for incident hypertension was 1.15 per 1% increase in RDW. When RDW was categorized, adjusted ORs significantly increased in Q2, Q3, and Q4 compared with Q1 (P for trend <0.001). The fully adjusted ORs were 1.19 (1.10–1.29), 1.28 (1.18–1.39) and 1.32 (1.22–1.44), respectively.

The addition of RDW quartiles significantly improved the C-statistic [95% CI] of the model predicting the development of hypertension (0.8379 [0.8336–0.8423] vs. 0.8372 [0.8329–0.8416], P < 0.001).

In the sensitivity analysis, the association between RDW categories and incident hypertension was similar across clinically relevant subgroups (Table 3). There were no significant interactions according to age (<40 years vs. ≥40 years), sex (female vs. male), BMI (<23.5 kg/m2 vs. ≥23.5 kg/m2), diabetes (no vs. yes), current smoking habit (no vs. yes), alcohol intake (<10 g/day vs. ≥10 g/day), vigorous exercise two or more times per week (no vs. yes), or hsCRP value (<0.02 mg/dL vs. ≥0.02 mg/dL).

Discussion

This large retrospective cohort study showed that the increases in systolic and diastolic BP and the numbers of new patients on hypertension medication were higher after 4 years in participants with high RDW levels. Overall, increased RDW categories were positively associated with an increased risk of incident hypertension. This association was independent of various traditional risk factors and potential mediators. In addition, the association between high RDW and incident hypertension was stronger in participants with higher RDW levels and persisted in different clinically relevant subgroups. Furthermore, adding RDW to a regression model significantly improved the prediction of incident hypertension.

The association between RDW and BP has been the subject of several previous studies. Tanindi et al. analyzed 128 patients with hypertension, 74 patients with prehypertension, and 36 healthy controls in Turkey and found that RDW is higher in prehypertensive and hypertensive patients than in healthy controls after adjusting for age, inflammatory status, and anemia [8]. In addition, there was a strong correlation between higher RDW levels and higher systolic and diastolic BP. A study by Gunebakmaz et al. analyzed 123 hypertensive patients and 65 age- and gender-matched normotensive subjects in Turkey. The patients were divided into dippers and nondippers according to their BP patterns at nighttime. Gunebakmaz et al. also found that hypertensive patients had higher RDW levels. Furthermore, compared with dipping, nondipping, which is a poor cardiovascular prognostic factor, was associated with higher RDW levels [11]. Jiang et al. analyzed 302,527 health checkup participants in China. Interestingly, the participants demonstrated an inverted U-shaped relationship between RDW and systolic and diastolic BP [12]. After adjusting for age, white blood cells, BMI, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, the risk of hypertension peaked at an RDW level of 14.2% in both men and women.

All three studies were cross-sectional studies. Recently, the first longitudinal study on RDW and hypertension was reported [13]. A study by Pilling et al. observed 240,477 healthy UK Biobank study volunteers without hypertension for a mean of 7 years. In their study, RDW was predictive of incident hypertension after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, education level, hemoglobin, MCV, smoking status, and physical activity. However, these authors did not measure BP and defined hypertension through self-reports or in-patient disease diagnosis with an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD)-10 code. Considering that the awareness of hypertension is only 40–60% [14], this lack is a major limitation in a study of hypertension. To our knowledge, our study is the first longitudinal study to verify the effects of RDW on changes in BP and the future development of hypertension.

The mechanism underlying the association between high RDW and the development of hypertension is uncertain, but we can suggest a few possibilities. First, high RDW may have a direct effect on hypertension through endothelial dysfunction. Patel et al. showed that elevated RDW is associated with decreased red blood cell deformability [15], which can cause regional circulation impairment and hypoxia [16]. Hypoxia is an important mechanism causing endothelial cell death and dysfunction [17]. A previous clinical study showed that high RDW is independently related to endothelial dysfunction measured by decreased flow-mediated dilatation [18]. Endothelial dysfunction is an important pathogenesis underlying hypertension, and a complex and bidirectional relationship exists between endothelial dysfunction and hypertension [19, 20]. Second, high RDW may be a mere marker of comorbidities or pathophysiology related to hypertension rather than a direct inducer of hypertension. Older age, obesity, and metabolic syndromes are associated with the high RDW and are also well-known risk factors for hypertension [21,22,23]. Similarly, high RDW is thought to be a sign of inflammation and oxidative stress [3], which are important pathogeneses underlying hypertension [20]. Although we attempted to adjust for these confounders or mediators in this analysis, it is impossible to completely eliminate their effects.

RDW is reported in routine CBCs and is therefore easily identified without additional costs. Because hypertension is the most important and preventable disease burden worldwide, it is meaningful that we found a new and simple risk-stratification tool for hypertension. Screening for hypertension with a regular checkup and preventing hypertension through lifestyle modification would be a reasonable approach for individuals with high RDW.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting this study. First, during the study period, BP-measuring technology changed from standard mercury sphygmomanometers (from 2005 to 2011) to automated oscillometric devices (from 2012 to 2016). However, a relatively large number of participants offset this limitation, and it is unlikely that BP differences from the different devices were unevenly distributed according to the RDW categories. Second, the study population comprised relatively young and healthy Korean adults participating in a health checkup program at a single center in Korea. Therefore, these findings might not be generalizable to other settings or other ethnicities. However, our study has multiple strengths, including the large sample size, the longitudinal design, the incorporation of well-organized and structured health checkup protocols, and detailed information on various risk factors related to hypertension.

In conclusion, high RDW was associated with an increased risk of incident hypertension. The association was independent of established risk factors, progressive with increased RDW, and preserved in different clinically relevant subgroups. Further research is required to elucidate the possible mechanisms responsible for this relationship. Individuals with high RDW need to be carefully monitored for the development of hypertension and are advised to apply measures to reduce the risk of hypertension.

References

Sarma PR. Red cell indices. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical methods: the history, physical, and laboratory examinations, 3rd ed. Butterworths: Boston; 1990. p. 720–3.

Marks PW. Approach to anemia in the adult and child. In: Hoffman R, editor. Hematology: basic principles and practice, 6th ed. Saunders/Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA; 2013. p. 418–26.

Salvagno GL, Sanchis-Gomar F, Picanza A, Lippi G. Red blood cell distribution width: a simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2015;52:86–105.

Li N, Zhou H, Tang Q. Red blood cell distribution width: a novel predictive indicator for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Dis Markers. 2017;2017:7089493.

Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–23.

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H. et al A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2224–60.

He FJ, MacGregor GA. Blood pressure is the most important cause of death and disability in the world. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2007;9 Suppl B:B23–B28.

Tanindi A, Topal FE, Topal F, Celik B. Red cell distribution width in patients with prehypertension and hypertension. Blood Press. 2012;21:177–81.

Danese E, Lippi G, Montagnana M. Red blood cell distribution width and cardiovascular diseases. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:E402–411.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12.

Gunebakmaz O, Kaya MG, Duran M, Akpek M, Elcik D, Eryol NK. Red blood cell distribution width in ‘non-dippers’ versus ‘dippers’. Cardiology. 2012;123:154–9.

Jiang M, Zha X, Wu Z, Zhu X, Li W, Wu H et al. Inverted U-shaped curve relationship between red blood cell distribution width and hypertension in a large health checkup population in China. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2018;12:327–34.

Pilling LC, Atkins JL, Kuchel GA, Ferrucci L, Melzer D. Red cell distribution width and common disease onsets in 240,477 healthy volunteers followed for up to 9 years. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0203504.

Pereira M, Lunet N, Azevedo A, Barros H. Differences in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension between developing and developed countries. J Hypertens. 2009;27:963–75.

Patel KV, Mohanty JG, Kanapuru B, Hesdorffer C, Ershler WB, Rifkind JM. Association of the red cell distribution width with red blood cell deformability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;765:211–6.

Simchon S, Jan KM, Chien S. Influence of reduced red cell deformability on regional blood flow. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H898–903.

Stempien-Otero A, Karsan A, Cornejo CJ, Xiang H, Eunson T, Morrison RS et al. Mechanisms of hypoxia-induced endothelial cell death. Role of p53 in apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8039–45.

Solak Y, Yilmaz MI, Saglam M, Caglar K, Verim S, Unal HU et al. Red cell distribution width is independently related to endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease. Am J Med Sci. 2014;347:118–24.

Brandes RP. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;64:924–8.

Dharmashankar K, Widlansky ME. Vascular endothelial function and hypertension: insights and directions. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:448–55.

Vaya A, Carmona P, Badia N, Hernandez-Mijares A, Bautista D. Association between high red blood cell distribution width and metabolic syndrome. Influence Abdom Obes Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2011;47:75–77.

Vaya A, Alis R, Hernandez-Mijares A, Sola E, Camara R, Rivera L et al. Red blood cell distribution width is not related with inflammatory parameters in morbidly obese patients. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:464–6.

Hoffmann JJ, Nabbe KC, van den Broek NM. Effect of age and gender on reference intervals of red blood cell distribution width (RDW) and mean red cell volume (MCV). Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53:2015–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article was partly presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2018 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, SG., Lee, MY., Park, S.H. et al. The association between red cell distribution width and incident hypertension in Korean adults. Hypertens Res 43, 55–61 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0334-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0334-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Red cell distribution width and related indices in relation to target-organ damage in children with hypertension

BMC Pediatrics (2025)

-

Acute ischemic stroke prediction and predictive factors analysis using hematological indicators in elderly hypertensives post-transient ischemic attack

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Blood indices of inflammation and their association with hypertension in smokers: analysis using data mining approaches

Journal of Human Hypertension (2024)

-

Development and validation of nomograms for predicting cardiovascular disease risk in patients with prediabetes and diabetes

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Red cell distribution width: a potential marker of reduced femoral neck bone mineral density in men and postmenopausal women

Endocrine (2024)