Abstract

Elevated aortic blood pressure is more strongly related to the onset of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than elevated brachial blood pressure. On the other hand, erectile dysfunction (ED) is a peripheral vascular disfunction and is also associated with CVD; however, the association between aortic blood pressure and ED has not yet been clarified. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the association between ED severity and aortic blood pressure in adult men. In 253 Japanese adult men (59 ± 16 years), aortic (estimated using a generalized transfer function) and peripheral hemodynamics were measured. Erectile function was assessed with a questionnaire (the International Index of Erectile Function 5: IIEF5), and participants were stratified into three groups based on the IIEF5 score (no ED, mild-to-moderate ED, and moderate-to-severe ED). Aortic systolic blood pressure (SBP) and pulse pressure (PP) were significantly higher in subjects with moderate-to-severe ED than in subjects with no ED or mild-to-moderate ED. In addition, the severity of ED was significantly associated with the time to reflection, augmentation pressure, and augmentation index. Multivariate linear regression analyses suggested that moderate-to-severe ED was significantly associated with aortic SBP and PP (β = 0.129; p = 0.047, β = 0.165; p = 0.013, respectively) but not brachial SBP or PP, after confounding factors were considered. These results suggest that moderate-to-severe ED is associated with elevated aortic blood pressure due to an earlier arrival of the reflected wave and is an independent predictor of elevated aortic blood pressure in Japanese men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide; an estimated 17.7 million people died from CVD in 2015, accounting for 31% of all global deaths that year [1]. Blood pressure is an independent risk factor for CVD, and central blood pressure is more strongly related to CVD than brachial blood pressure [2,3,4]. Previously, central blood pressure was evaluated using a catheter, which was an invasive strategy that could not be efficiently applied in daily medical practice. Although noninvasive methods have recently been developed, they have not been sufficiently implemented in clinical practice. Moreover, it is now widely recognized that hypertension is a “silent killer” [5, 6], with no subjective symptoms present when blood pressure is elevated. Thus, it is necessary to establish subjective markers that reflect elevated blood pressure, especially central blood pressure.

Erectile dysfunction (ED), defined as an inability to attain or maintain penile erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance [7], is another common clinical problem worldwide [8, 9]. It is now widely accepted that ED is not only a sexual dysfunction but also a vascular dysfunction [10, 11]. Indeed, several studies have reported that ED is a risk factor for CVD [12, 13], and a previous meta-analysis suggested that men with ED exhibited significantly higher risks for CVD (48%), coronary heart disease (46%), and stroke (35%) than men without ED [14]. In addition, it has been shown that the onset of ED was earlier than that of coronary artery disease in most patients with chronic coronary syndrome by a mean time interval of 24 months [15]. Taken together, these studies suggest that ED could potentially be an early indicator of CVD risks, such as elevated brachial blood pressure and central blood pressure. However, these possible associations remain poorly understood.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the association between erectile function and central blood pressure in adult men. We hypothesized that ED is associated with central blood pressure and, more specifically, that deteriorating erectile function could be a potential subjective marker of elevated central blood pressure. To test our hypothesis, we assessed erectile function and central blood pressure in a cross-sectional study of Japanese adult men.

Materials and methods

Participants

We recruited subjects using local newspaper advertisements. A total of 253 adult Japanese men (age range: 23–88 years old) participated in this study. The number of participants who used antihypertensive medication, antihypercholesterolemic medication, and antihyperglycemic medication were 67 (26.5%), 34 (13.4%), and 14 (5.5%), respectively. Moreover, seven (2.8%) participants had a history of angina, three (1.2%) participants had a history of myocardial infarction, and six (2.4%) participants had a history of stroke. Sixteen (6.3%) participants were current smokers. We excluded participants who underwent ED treatment and who lacked central hemodynamic or sexual function data. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Health and Sport Sciences at the University of Tsukuba. The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all participants were asked to provide written informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Anthropometric measurements

A digital scale was used to measure body weight to the nearest 0.1 kg. A wall-mounted stadiometer was used to measure height to the nearest 0.1 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the participants’ weight (kg) by their height (m2).

Blood biochemistry

Blood samples were collected from each subject in the morning after a 12-h overnight fast. Serum concentrations of triglycerides, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and plasma concentrations of glucose and HbA1c were determined using standard enzymatic techniques. Serum total testosterone levels were measured using a chemiluminescent immunoassay in a commercial laboratory (LSI medience, Ibaraki, Japan).

Hemodynamic parameters

Brachial systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured by a semiautomatic vascular testing device equipped with oscillometric extremity cuffs (form PWV/ABI; Colin, Komaki, Japan). Pulse pressure (PP) was calculated as the difference between systolic and DBP. The mean arterial pressure was calculated as DBP plus one-third of the PP. The pressure waves at the carotid artery were recorded with an applanation tonometry sensor (form PWV/ABI; Colin, Komaki, Japan). Using general transfer function-based pulse wave analysis software (SphygmoCor version 8.0, AtCor Medical, Australia), central (aortic) pressure pulse waves were computed from the carotid pressure waveforms as we reported previously [16, 17]. Based on the physiological principle that mean and DBPs remain almost unchanged from the central elastic artery to the peripheral muscular artery, the aortic pressure waveforms were calibrated by brachial mean and DBP [18]. Augmentation pressure (AP) was calculated as the difference between the early and late systolic peaks of the synthesized aortic pressure waveform, and the augmentation index (AI) was calculated as the ratio of augmented pressure to PP. Time to reflection was defined as the round-trip travel time of the pressure waveform between the heart and the effective reflection site and was calculated as the time lag between the initial upstroke of aortic pressure and the systolic inflection point.

Male sexual function

Erectile function was assessed by using a questionnaire: the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) 5. The IIEF questionnaire has been adopted as the gold standard for ED assessment [19] and was developed and validated in 1997 [20]. The IIEF5 is the short form of the IIEF, and IIEF5 scores range from 5 to 25 points; lower scores indicate worse erectile function. According to previous studies, individuals with 5–11 points on the IIEF5 were diagnosed with moderate-to-severe ED, those with 12–21 points were diagnosed with mild-to-moderate ED, and those with 22–25 points were diagnosed with no ED [21, 22].

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess the normality of all parameters. Data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SDs) or frequency counts (for categorical data). Values were analyzed using the Tukey–Kramer test or the Steel–Dwass test, as appropriate. The relationship between the IIEF5 score and hemodynamics was analyzed using linear and/or curvilinear regression analyses. The variables with skewed distributions were log-transformed to obtain normal distributions before multivariate linear regression analyses were performed. Independent correlates of log-transformed SBP and PP were examined using multivariate linear regression analysis. Age, height, BMI, HDL-cholesterol levels, LDL-cholesterol levels, triglyceride levels, medication use, smoking, history of angina, history of myocardial infarction, history of stroke, and ED severity were included in the multivariate linear regression models as covariates. ED severity was included as three categories and as ordinal numbers to test for a trend. Statistical significance for all comparisons was set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed). Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro version 12 (SAS Institute).

Results

The characteristics of the studied subjects are summarized in Table 1. The IIEF5 score was significantly correlated with brachial SBP (r = −0.255, p < 0.001), brachial DBP (r = −0.175, p = 0.005), brachial PP (r = −0.179, p = 0.004), aortic SBP (r = −0.281, p < 0.001), aortic DBP (r = −0.174, p = 0.006), and aortic PP (r = −0.223, p < 0.001). Serum testosterone levels were significantly correlated with brachial SBP (r = −0.206, p = 0.001), brachial DBP (r = −0.254, p < 0.005), aortic SBP (r = −0.210, p < 0.001), aortic DBP (r = −0.254, p < 0.001), and BMI (r = −0.292, p < 0.001) but not age (r = −0.089, p = 0.159).

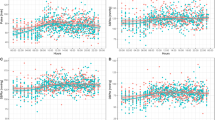

The subjects with ED exhibited significantly higher brachial SBP (119 ± 9 vs. 127 ± 14 mmHg, p < 0.001), brachial DBP (74 ± 9 vs. 79 ± 9 mmHg, p < 0.001), brachial PP (45 ± 6 vs. 48 ± 9 mmHg, p < 0.001), aortic SBP (107 ± 10 vs. 116 ± 13 mmHg, p < 0.001), aortic DBP (74 ± 9 vs. 79 ± 9 mmHg, p < 0.001), and aortic PP (33 ± 6 vs. 37 ± 8 mmHg, p < 0.001). Table 2 shows the characteristics of the subjects classified by ED severity. Age, height, glucose, and HbA1c were significantly different between each group. Brachial and aortic SBP, DBP, PP, APHR75, AIHR75, and time to reflection were significantly different between the ED severity groups (Table 2) (Fig. 1). Interestingly, although the IIEF5 score was significantly correlated with APHR75, AIHR75 and time to reflection in both the linear (R2 = 0.171, R2 = 0.146, R2 = 0.158, respectively) and curvilinear (R2 = 0.183, R2 = 0.187, R2 = 0.176, respectively) regression analyses, the curvilinear regressions showed higher R2 values than the linear regressions (Fig. 2).

To investigate the further associations between brachial and aortic blood pressure and ED severity, we applied a multivariate linear regression analysis (Table 3). Age, height, BMI, HDL-cholesterol levels, LDL-cholesterol levels, triglyceride levels, medications, smoking, history of angina, history of myocardial infarction, history of stroke, and ED severity were included in the multiple linear regression models as covariates. The severity of ED as an ordinal number (test for trend) was not significantly associated with log-transformed brachial SBP (β = 0.037; 95% CI = −0.008, 0.015; p = 0.578), brachial PP (β = 0.072; 95% CI = −0.009, 0.028; p = 0.314), aortic SBP (β = 0.099; 95% CI = −0.003, 0.021; p = 0.147), or aortic PP (β = 0.070; 95% CI = −0.011, 0.033; p = 0.317). On the other hand, moderate-to-severe ED was significantly associated with log-transformed aortic SBP (β = 0.129; 95% CI = 0.000, 0.040; p = 0.047) and aortic PP (β = 0.165; 95% CI = 0.010, 0.080; p = 0.013) but not brachial SBP (β = 0.026; 95% CI = −0.015, 0.023; p = 0.681) or brachial PP (β = 0.122; 95% CI = −0.002, 0.057; p = 0.071) (Table 3). Furthermore, after including brachial SBP as a covariate, moderate-to-severe ED was significantly associated with aortic SBP (β = 0.113; 95% CI = 0.002, 0.033; p = 0.031) and aortic PP (β = 0.151; 95% CI = 0.011, 0.071; p = 0.008).

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the association between penile erectile function and blood pressure in adult Japanese men. Although the degree of severity of ED was significantly associated with both brachial and aortic SBP and PP, multivariate linear regression analyses suggested that ED was only significantly associated with aortic SBP and PP after confounding factors were taken into consideration. On the other hand, the IIEF5 score was significantly associated with time to reflection, APHR75, and AIHR75. These results suggest that the deterioration of erectile function, as assessed via a questionnaire, is associated with elevated aortic blood pressure through an earlier arrival of the reflected wave and is an independent predictor of elevated aortic blood pressure in Japanese men.

It has been suggested that ED is an indicator of future CVD events [14, 23]. Although several previous studies have reported that atherosclerosis [13, 24, 25], endothelial dysfunction [12], and arterial stiffness [11] were associated with erectile function, the relationship between central hemodynamics, a strong predictor of CVD [2,3,4, 26, 27], and ED was poorly understood. The present study demonstrated that the IIEF5 score, as an index of erectile function, was significantly correlated with both brachial and central blood pressure. After confounding factors were considered, moderate-to-severe ED was associated with only central blood pressure but not brachial blood pressure. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the influence of ED on brachial and central blood pressure and demonstrated that moderate-to-severe ED is significantly associated with elevated central blood pressure. These findings provide a possible new explanation for the association between ED and CVD.

Vlachopoulos et al. reported that CVD risk was higher in hypertensive patients with ED than in patients without ED [28]. Supporting the results of this study, we recently demonstrated that ED was significantly associated with elevated arterial stiffness in adult men [11]. These studies suggest that men with ED exhibit higher CVD risk than men without ED. In addition to these findings and in line with the results of Vlachopoulos et al., the risks of CVD and major adverse cardiovascular events were significantly different, even in patients with ED [11, 29], which suggests that a more detailed classification is necessary for predicting CVD risk in patients with ED. The present study demonstrated that only moderate-to-severe ED was associated with aortic blood pressure but not mild-to-moderate ED. Taken together, previous findings and our present results suggest that a detailed classification of ED is effective for identifying increased CVD risk in adult men.

The present result that only moderate-to-severe ED was associated with elevated aortic blood pressure may reflect the progression of atherosclerosis pathology. Aortic blood pressure is composed of a wave elicited by the left ventricular ejection and a reflected wave from the peripheral vasculature [30]. Since the stiffened artery causes the wave to travel faster and return earlier than does a nonstiffened artery, it elevates aortic blood pressure. In the present study, although the time to reflection, as a marker of arterial stiffness [11], was shortened with the lowering of the IIEF5 score in the subjects with over 12 points on the IIEF5, the relationship almost plateaued in the subjects with under 12 points on the IIEF5 (Fig. 2c), which suggests the presence of a factor other than a stiffened artery. It is well known that the progression of atherosclerosis is associated with atherosclerotic plaques, and the presence of plaques may move the reflection point closer to the central artery. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that atherosclerotic plaque was present in the femoral artery in ED patients [31]. Overall, it is possible that moderate-to-severe ED reflects the existence of atherosclerotic plaques because only moderate-to-severe ED was associated with elevated aortic blood pressure in the present study.

Testosterone, the primary male sex hormone, is associated with both cardiovascular and erectile function [32,33,34], and the administration of testosterone improves both cardiovascular and erectile function [35,36,37]. However, although serum testosterone levels were significantly correlated with brachial and aortic blood pressure, there were no significant differences between the no ED, mild-to-moderate ED, and moderate-to-severe ED groups. This inconsistent result regarding the relationship between testosterone and ED may be caused by differences in circulating testosterone levels. A previous study in subjects with normal testosterone levels demonstrated that there was no significant relationship between circulating testosterone levels and sexual function assessed by the Aging Males’ Symptoms questionnaire [38], which supports our present result. In addition, testosterone replacement therapy is available for patients with low testosterone levels, not for patients with normal testosterone levels. These results implied that circulating testosterone levels below the normal range may be associated with ED in men.

Aging is the leading cause of lower circulating testosterone levels and reductions in circulating testosterone levels by ~1.6%/year in the Western population [39]. However, it has been suggested that aging did not influence circulating testosterone levels in the Japanese population [40], and the present study showed a similar result in adult Japanese men. However, circulating testosterone levels were significantly correlated with BMI (r = −0.292, p < 0.001). Taken together, these results suggest that circulating total testosterone levels are influenced by obesity and not aging in the Japanese population.

The present study has several limitations. First, the participants were recruited using local newspaper advertisements, which may limit recruitment to the relatively healthy population and a limited ethnicity. Indeed, the levels of serum total testosterone were within the normal range, and the ethnicity of the population was only Japanese. Second, the present assessment could not eliminate the possibility of misclassification since male sexual function was assessed by only a self-reported questionnaire. Although several studies have demonstrated the objective assessment of ED using ultrasound, this method has substantial ethical problems in the general population. Third, the details of antihypertensive drug use were not considered in the present study. It has been reported that the effects of specific antihypertensive drugs, such as angiotensin II receptor blockers, diuretics, and beta-blockers, on erectile function were different [41,42,43]. In summary, further studies that consider these limitations are necessary.

In the present study, we investigated the association between penile erectile function and blood pressure in adult Japanese men. Although ED severity was significantly associated with both brachial and aortic blood pressure, multivariate linear regression analyses suggested that ED severity, especially moderate-to-severe ED, was significantly associated with only aortic blood pressure after age and brachial blood pressure were taken into consideration. On the other hand, the IIEF5 score was significantly correlated with time to reflection, APHR75 and AIHR75, which suggested that erectile function was associated with elevated aortic blood pressure due to an earlier arrival of the reflected wave from the peripheral vasculature. Overall, the deterioration of erectile function, as assessed via a simple questionnaire, has the potential to be a personal and independent marker of central hypertension, which is known as a “silent killer.” Earlier detection of elevated central blood pressure based on male erectile function may contribute to the preventive or treatment of CVD.

References

World Health Organization. Cardiovascular disease. Fact sheet on CVDs. World Health Organization; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovasculardiseases-(cvds) 2017.

Kollias A, Lagou S, Zeniodi ME, Boubouchairopoulou N, Stergiou GS. Association of central versus brachial blood pressure with target-organ damage: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2016;67:183–90.

Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kizer JR, Lee ET, Galloway JM, Ali T, et al. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the strong heart study. Hypertension. 2007;50:197–203.

Wang KL, Cheng HM, Chuang SY, Spurgeon HA, Ting CT, Lakatta EG, et al. Central or peripheral systolic or pulse pressure: which best relates to target organs and future mortality? J Hypertens. 2009;27:461–7.

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2013 update: a report from the american heart association. Circulation . 2013;127:e6–e245.

World Health Organization. A global brief on hypertension. World Health Organization; https://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/global_brief_hypertension/en/ 2013.

Yafi FA, Jenkins L, Albersen M, Corona G, Isidori AM, Goldfarb S, et al. Erectile dysfunction. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2016;2:16003.

Ayta IA, McKinlay JB, Krane RJ. The likely worldwide increase in erectile dysfunction between 1995 and 2025 and some possible policy consequences. BJU Int. 1999;84:50–56.

Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the massachusetts male aging study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61.

Nehra A. Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease: efficacy and safety of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in men with both conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:139–48.

Kumagai H, Yoshikawa T, Myoenzono K, Kosaki K, Akazawa N, Asako ZM, et al. Sexual function is an indicator of central arterial stiffness and arterial stiffness gradient in japanese adult men. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007964.

Vlachopoulos C, Ioakeimidis N, Terentes-Printzios D, Stefanadis C. The triad: erectile dysfunction-endothelial dysfunction-cardiovascular disease. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:3700–14.

Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, Rotatori F, Briganti A, Salonia A, et al. The artery size hypothesis: a macrovascular link between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(12B):19M–23M.

Dong JY, Zhang YH, Qin LQ. Erectile dysfunction and risk of cardiovascular disease: Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1378–85.

Montorsi P, Ravagnani PM, Galli S, Rotatori F, Veglia F, Briganti A, et al. Association between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease. Role of coronary clinical presentation and extent of coronary vessels involvement: the cobra trial. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2632–9.

Yoshikawa T, Zempo-Miyaki A, Kumagai H, Myoenzono K, So R, Tsujimoto T, et al. Relationships between serum free fatty acid and pulse pressure amplification in overweight/obese men: Insights from exercise training and dietary modification. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2018;62:254–8.

Tagawa K, Choi Y, Ra SG, Yoshikawa T, Kumagai H, Maeda S. Resistance training-induced decrease in central arterial compliance is associated with decreased subendocardial viability ratio in healthy young men. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43:510–6.

Kelly R, Fitchett D. Noninvasive determination of aortic input impedance and external left ventricular power output: a validation and repeatability study of a new technique. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:952–63.

Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Gendrano N 3rd. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a state-of-the-science review. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:226–44.

Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–30.

Bohm M, Baumhakel M, Teo K, Sleight P, Probstfield J, Gao P. Investigators OTEDS et al. Erectile dysfunction predicts cardiovascular events in high-risk patients receiving telmisartan, ramipril, or both: the ongoing telmisartan alone and in combination with ramipril global endpoint trial/telmisartan randomized assessment study in ace intolerant subjects with cardiovascular disease (ontarget/transcend) trials. Circulation. 2010;121:1439–46.

Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Pena BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the international index of erectile function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–26.

Gazzaruso C, Solerte SB, Pujia A, Coppola A, Vezzoli M, Salvucci F, et al. Erectile dysfunction as a predictor of cardiovascular events and death in diabetic patients with angiographically proven asymptomatic coronary artery disease: a potential protective role for statins and 5-phosphodiesterase inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2040–4.

Gandaglia G, Briganti A, Jackson G, Kloner RA, Montorsi F, Montorsi P, et al. A systematic review of the association between erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Eur Urol. 2014;65:968–78.

Montorsi P, Montorsi F, Schulman CC. Is erectile dysfunction the “tip of the iceberg” of a systemic vascular disorder? Eur Urol. 2003;44:352–4.

Eguchi K, Miyashita H, Takenaka T, Tabara Y, Tomiyama H, Dohi Y, et al. High central blood pressure is associated with incident cardiovascular events in treated hypertensives: the abc-j ii study. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:947–56.

Sun P, Yang Y, Cheng G, Fan F, Qi L, Gao L, et al. Noninvasive central systolic blood pressure, not peripheral systolic blood pressure, independently predicts the progression of carotid intima-media thickness in a chinese community-based population. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:392–9.

Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Ioakeimidis N, Rokkas K, Tsekoura D, Vasiliadou C, et al. Arterial function and intima-media thickness in hypertensive patients with erectile dysfunction. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1829–36.

Vlachopoulos C, Ioakeimidis N, Aznaouridis K, Terentes-Printzios D, Rokkas K, Aggelis A, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular events with aortic stiffness in patients with erectile dysfunction. Hypertension. 2014;64:672–8.

O’Rourke MF, Hashimoto J. Mechanical factors in arterial aging: a clinical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1–13.

Goksu C, Deveer M, Sivrioglu AK, Goksu P, Cucen B, Parlak S, et al. Peripheral atherosclerosis in patients with arterial erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2014;26:55–60.

Vlachopoulos C, Ioakeimidis N, Miner M, Aggelis A, Pietri P, Terentes-Printzios D, et al. Testosterone deficiency: a determinant of aortic stiffness in men. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233:278–83.

Akishita M, Hashimoto M, Ohike Y, Ogawa S, Iijima K, Eto M, et al. Low testosterone level as a predictor of cardiovascular events in Japanese men with coronary risk factors. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210:232–6.

Caminiti G, Volterrani M, Iellamo F, Marazzi G, Massaro R, Miceli M, et al. Effect of long-acting testosterone treatment on functional exercise capacity, skeletal muscle performance, insulin resistance, and baroreflex sensitivity in elderly patients with chronic heart failure a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:919–27.

Rizk PJ, Kohn TP, Pastuszak AW, Khera M. Testosterone therapy improves erectile function and libido in hypogonadal men. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27:511–5.

Saad F, Caliber M, Doros G, Haider KS, Haider A. Long-term treatment with testosterone undecanoate injections in men with hypogonadism alleviates erectile dysfunction and reduces risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, prostate cancer, and mortality. Aging Male. 2019:1–12. [Epub ahead of print].

Traish AM, Haider A, Doros G, Saad F. Long-term testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men ameliorates elements of the metabolic syndrome: an observational, long-term registry study. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:314–29.

T’Sjoen G, Feyen E, De Kuyper P, Comhaire F, Kaufman JM. Self-referred patients in an aging male clinic: much more than androgen deficiency alone. Aging Male. 2003;6:157–65.

Feldman HA, Longcope C, Derby CA, Johannes CB, Araujo AB, Coviello AD, et al. Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:589–98.

Okamura K, Ando F, Shimokata H. Serum total and free testosterone level of japanese men: a population-based study. Int J Urol. 2005;12:810–4.

Della Chiesa A, Pfiffner D, Meier B, Hess OM. Sexual activity in hypertensive men. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:515–21.

Doumas M, Tsakiris A, Douma S, Grigorakis A, Papadopoulos A, Hounta A, et al. Factors affecting the increased prevalence of erectile dysfunction in greek hypertensive compared with normotensive subjects. J Androl. 2006;27:469–77.

Llisterri JL, Lozano Vidal JV, Aznar Vicente J, Argaya Roca M, Pol Bravo C, Sanchez Zamorano MA, et al. Sexual dysfunction in hypertensive patients treated with losartan. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321:336–41.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the research members of S.M.’s laboratory at the University of Tsukuba for their technical assistance, Dr Tsubasa Tomoto at the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine for his assistance with data analyses, and Dr Noriyuki Fuku and Dr Tetsuhiro Kidokoro at Juntendo University for their statistical assistance. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research KAKENHI from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (15K12692 to Seiji Maeda). HK and KK were recipients of a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellow from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kumagai, H., Yoshikawa, T., Kosaki, K. et al. Deterioration of sexual function is associated with central hemodynamics in adult Japanese men. Hypertens Res 43, 36–44 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0336-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0336-1