Abstract

Preeclampsia (PE) is a major obstetrical complication that results in maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Aberrant epigenetic modifications are widely involved in the pathogenesis of PE. Previously, the activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM) was reported to be required for blastocyst implantation but has not been described in the context of pathological pregnancy. This study explored the expression of ALCAM and its methylation levels in the placentas and peripheral venous blood of patients with PE from a Chinese Han population. The mRNA and protein expression levels of ALCAM were downregulated in the PE placentas compared with the control placentas (P < 0.05). The methylation rate of the ALCAM gene promoter was considerably elevated in the placentas (P = 0.003, odds ratio (OR) = 0.264, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) [0.108–0.647], cases n = 47, controls n = 53) and peripheral blood (P = 0.007, OR = 0.455, 95% CI [0.256–0.806], cases n = 100, controls n = 100) of the PE patients compared with those of the normotensive women, suggesting a negative relationship between ALCAM methylation and gene transcription. Moreover, the transcriptional expression of ALCAM was dramatically increased by demethylating treatment in trophoblastic cells. ALCAM is expected to be involved in the pathogenesis of PE through methylation regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Preeclampsia (PE) is a serious pregnancy-specific disorder characterized by de novo hypertension and excess proteinuria, along with other systemic disorders; furthermore, PE affects 5–8% of all pregnancies worldwide and is a major obstetrical complication that results in maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality [1]. Regarding mothers, it is well documented that PE increases the risk of placental abruption, preterm delivery, chronic hypertension, renal failure, seizures, circulatory failure, and death. Regarding the fetus, the adverse consequences of PE are intrauterine growth restriction, fetal distress, and intrauterine death [2]. The clinical manifestations of PE probably represent the late stage of the disease, and PE may progress to eclampsia due to delayed diagnosis and treatment, resulting in more serious outcomes [3]. However, the etiology of PE remains poorly understood, and thus far, delivery of the placenta is the only cure for PE. Despite the increasing number of scientific efforts to explore the pathological and clinical aspects of PE, the incidence of this disease is not declining and is still the main cause of maternal mortality. Therefore, efforts toward the development and assessment of efficient diagnostic and treatment strategies are urgently needed for women and fetuses affected by PE.

The activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM), a member of the cell surface immunoglobulin superfamily, is expressed in a wide variety of cell types, including trophoblastic, endothelial, hematopoietic, and epithelial cells, and regulates cell motility, invasiveness, and adhesion [4]. Previous studies have shown that ALCAM may be involved in numerous developmental events and has been identified as a marker for the progression of various diseases [4, 5]. In the context of pregnancy, developmental biology studies have shown that ALCAM expression is required for blastocyst implantation [6]. Microarray analysis revealed the downregulation of ALCAM in PE placental tissue and decreased secretion of ALCAM in BeWo cells treated with PE serum in vitro [7, 8]. However, the effect of ALCAM on PE and the underlying mechanisms are largely unclear and of great interest to researchers in the field.

Epigenetic mechanisms, which reflect heritable changes to the genome that do not involve changes to the underlying DNA sequence, play an important role in the pathogenesis of PE [9,10,11,12,13,14]. In addition, abnormal CpG island methylation in the human genome, especially in the promoter region, is closely related to gene silencing [15]. Furthermore, methylation and demethylation of some specific genes can change gene expression during the differentiation of trophoblastic cells, affecting the physiological function of trophoblastic cells and participating in the onset of PE [10, 11, 16,17,18,19]. Therefore, studying DNA methylation can yield more information about the pathological changes of PE.

Based on the speculation that variations in ALCAM expression that are caused by the altered methylation status of the gene promoter might play important roles in the pathologies of PE, the aim of this study was to explore the correlation between ALCAM promoter methylation and PE, which may provide a genetic basis for the early diagnosis and treatment of this disorder.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This case–control study enrolled 100 PE patients and 100 control subjects recruited from the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University from January 2015 to November 2017. PE cases were defined according to the criteria set by the Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand [20], namely, systolic pressure ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic pressure ≥90 mmHg on two occasions at least 4 h apart and proteinuria (≥2+ on dipstick or 300 mg/24 h) that developed after the 20th week of gestation. The controls consisted of healthy women without hypertension, without hypertension-related complications and who presented for delivery at term (≥37-week gestation). The PE and healthy subjects had no history of hypertension. Severe PE was characterized either by higher blood pressure (SBP ≥ 160 mmHg or DBP ≥ 110 mmHg) or by severe proteinuria (≥5 g protein in a 24-h urine collection). Subjects exhibiting any factor that may influence methylation patterns, including prenatal smoking, drinking, chronic diseases, or assisted reproduction, were excluded from this study.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, and written consent was obtained from all of the pregnant subjects before the collections of the placentas and blood.

Sample collection

Placental samples from normal and PE pregnancies were collected for this case–control study. Two tissue samples (1.0 cm × 1.0 cm) were dissected from the placenta of the maternal face soon after each elective cesarean section. After the maternal blood cells were removed by washing the tissue in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), one block of tissue was fixed in 4% formalin for immunohistochemistry (IHC), and the remaining tissue was maintained in centrifuge tubes and RNAlater (KangWei Century, China) and then stored at −80 °C.

Approximately 2 ml of maternal peripheral blood from PE cases and controls was extracted in the last trimester. Blood samples were collected in ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes and stored at −80 °C until use.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and quantitative real-time PCR

The placenta tissue samples to be analyzed for mRNA expression were harvested and immediately immersed in the RNA stabilization reagent and stored at −80 °C until use. mRNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA) and reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Takara kit (Takara Bio Inc., Japan).

ALCAM and β-actin sequences were amplified simultaneously by a duplex assay as described previously. The specific primers for human ALCAM were sense, 5′-CAGATTGGTGATGCCCTAC-3′, and antisense, 5′-GAGCAGTTTCGCAGACATAG-3′. The primers for human β-actin were sense, 5′-ATCTGGCACCACACCTTC-3′, and antisense, 5′-AGCCAGGTCCAGACGCA-3′.

Protein extraction and western blotting analysis

Placental protein was extracted with RIPA buffer (Biyuntian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Extracts that contained equal amounts of total protein were resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Next, the membranes were blocked in PBS/Tween-20 with 5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight with primary antibodies (Proteintech, China; ALCAM: 1/600; β-actin: 1/6000) at 4 °C. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG as a secondary antibody was used to bind primary antibodies, and β-actin was used as an endogenous control. The fluorescence signal was visualized with the luminescence substrate for HRP and examined by means of Image J software.

Immunohistochemistry

For IHC staining, the placentas were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 3-mm-thick sections. After incubation at 60 °C for 2 h, the slides were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in a graded alcohol series and washed in running water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 15 min. For antigen retrieval, the slides were incubated in 0.01 M EDTA buffer at 100 °C for 30 min. The sections were incubated with rabbit monoclonal antibodies directed against ALCAM (CST, USA; dilution 1:200) at 37 °C for 1 h followed by 4 °C overnight in a humidified chamber. An HRP-labeled secondary antibody was incubated with the slides for 1 h at 37 °C. Negative controls were generated by omitting the primary antibody. All images were captured by an Olympus microscope and evaluated by means of Image J software.

DNA extraction and bisulfite conversion

Genomic DNA was extracted from stored peripheral blood and placental tissue using the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA concentration was evaluated using a microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher, USA). Purified DNA with an optical density (OD) value between 1.8 and 2.0 was assumed to be of good quality. A total of 800 ng of DNA from the blood samples and 2.0 μg of DNA from the placental samples were modified using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (ZYMO RESEARCH, USA). The modified DNA was stored at −20 °C.

DNA methylation-specific PCR (MSP)

Methylation-specific primers were designed based on the promoter sequence of ALCAM. The primer sequences were forward, 5′-TGTTTTGCGTTGCGTTCGGGGA-3′, and reverse, 5′-ACAACAACGACGACAACGATCT-3′, for the methylated promoter and forward, 5′-TGTTTTGTGTTGTGTTTGGGGA-3′, and reverse, 5′-ACAACAACAACAACAACAATCT-3′, for the unmethylated promoter. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) regimen was as follows: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The 139-bp MSP products were isolated using electrophoresis in a 2.0% agarose gel and analyzed using an ultraviolet (UV) gel imaging system (Bio-Rad, CA).

Cell culture and treatment

The trophoblast-like cell line HTR-8/SVneo was purchased from Cell Bank (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai). The cells were maintained in DMEM (HyClone, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. Demethylating treatment was carried out with 5-Aza-dC (Sigma) at different concentrations of 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM for 24 h or at 2.5 μM for different time courses. Cells were cultured for 12 h before treatment at a confluency of 80–90%. The cells were then collected for subsequent experiments.

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The statistical significance of the variances was determined by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test, the chi-square test, or Student’s t test for comparisons. Statistical analyses involved the use of GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc, CA). Differences of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the PE cases and controls

A total of 100 PE patients and 100 control subjects were recruited for this case–control study. Blood samples were collected from all participants, and 53 control and 47 PE placental samples were collected. Specifically, the PE placental samples were taken from patients with severe PE. The clinical characteristics of the PE cases and controls, including those of the placental and blood samples, are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age or age at menarche between the two groups in either the placental or blood samples. However, in both the placental and blood samples, the BMI and blood pressure, including the systolic blood pressure and the diastolic blood pressure, were significantly higher in the PE group than in the normal control group. The gestational age and fetal weight of the PE cases were significantly lower than those of the normal controls.

Decreased ALCAM mRNA expression in PE placentas

First, we performed reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction to measure the mRNA expression levels of ALCAM in the placentas. The results showed that the mRNA expression of ALCAM was downregulated in the PE placentas compared with the control placentas (CTL vs. PE: 2.472 ± 0.6261, n = 23 vs. 0.9424 ± 0.2461, n = 23, P < 0.05) (Fig. 1).

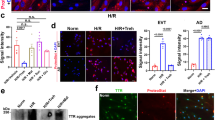

Decreased ALCAM protein expression in PE placentas

Western blotting was used to assess the protein expression of ALCAM in PE and normal placentas. The results showed that ALCAM expression was significantly reduced in the PE group compared with the control group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2a, b).

Decreased ALCAM protein expression in the preeclampsia placenta. Decreased protein expression of ALCAM is found in preeclampsia placentas. a Western blotting analysis of ALCAM protein expression in preeclampsia and normal placentas. b Statistical analysis of the protein densitometry quantification of western blots (A) by Student’s t test. c Representative images of ALCAM expression and localization in the placental tissue by IHC analysis (magnification ×200). The brownish color represents ALCAM staining. Arrows, syncytiotrophoblasts. The negative IgG control, involving a section of normal placenta, was processed with the same procedures, but with a primary antibody. CTL, IHC staining of normal placental tissue. PE, IHC staining of preeclampsia placental tissue

To further evaluate differences in the protein expression of ALCAM in the placental tissues of the PE and healthy control groups, we performed IHC staining. The results showed that ALCAM was mainly located in syncytiotrophoblasts and that the staining intensity of ALCAM in the placental tissues of the control group was stronger than that in the tissues of the PE group, indicating downregulated expression of ALCAM protein in PE placentas (Fig. 2c).

Hypermethylation of ALCAM in PE placentas compared with control placentas

To investigate the methylation status of the ALCAM promoter, PE placentas were analyzed by methylation-specific PCR (Fig. 3). The methylation frequency in the ALCAM gene promoter of the placental tissue was different between the control and PE cases: the hemimethylated status frequencies were 46.81% (22/47) in the PE group and 18.87% (10/53) in the normal group, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.003, OR = 0.264, 95% CI [0.108–0.647]) (Table 2).

Hypermethylation of ALCAM in the PE placenta. Electrophoresis pattern of promoter methylation of the ALCAM gene methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (MSP) products in the placental tissue. M represents methylation-specific primers; U represents unmethylated-specific primers. The samples shown in the figure are all randomly selected samples

The relationship between clinical characteristics and methylation status is presented in Table 3. No difference was observed in maternal age and age of menarche among the PE cases, the normal controls, and all participants with different methylation statuses. However, the gestational age and fetal weight were significantly lower in women with hemi-methylated promoters compared with unmethylated promoters in all participants but not in the PE or control women separately. The BMI was higher in PE women with an unmethylated promoter. Therefore, we considered that gestational age, fetal weight, and BMI may be major contributors to altered DNA methylation. To overcome this, we adjusted our analysis by gestational age, fetal weight, and BMI. The results showed that there was also differential methylation between PE cases and normal controls (adjusted P = 0.009, OR = 5.859, 95% CI [1.547–22.196]).

Methylated ALCAM DNA in maternal plasma is associated with PE

We further determined whether methylation of the ALCAM promoter in maternal blood could serve as a marker of PE by measuring levels. Similarly, MSP showed that the methylation frequency of the ALCAM gene promoter in the peripheral blood was also significantly different (Fig. 4). The overall methylation rate (UM + MM) was 52.00% and 33.00% in the PE and control groups, respectively, which was significantly higher in PE women (P = 0.007, OR = 0.455, 95% CI [0.256–0.806]). Consistent with the difference in overall methylation, the frequency of hemimethylated status was 44.00% in the PE group and 31.00% in the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.022, OR = 1.981, 95% CI [1.098–3.576]). However, no difference was detected between the unmethylated status and methylated status (P = 0.340, OR = 2.818, 95% CI [0.560–14.187]), wherein the frequencies of the methylated status were 8.00% and 2.00% in the PE and control groups, respectively (Table 4).

Methylated ALCAM DNA in maternal plasma is associated with PE. Electrophoresis pattern of promoter methylation of ALCAM gene methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (MSP) products in the peripheral blood. M represents methylation-specific primers; U represents unmethylated-specific primers. The samples shown in the figure are all randomly selected samples

We further compared the differences in methylation status between different samples, and the results showed that there were no significant differences in the overall methylation rate or unmethylation rate between the two samples (Table 5).

When the PE patients were divided into mild PE (n = 14) and severe PE (n = 86), there was no statistically significant difference between them in terms of the methylation frequencies of the ALCAM gene promoter region. The overall methylated status of the mild PE and severe PE patients was significantly different from that of the control group, although hemimethylated status and methylated status were not detected (Table 6).

ALCAM expression is regulated by DNA methylation in trophoblastic cells

To further confirm the role of DNA methylation in the deregulation of ALCAM in trophoblastic cells, we evaluated the effect of the methylation inhibitor 5-Aza-dC on ALCAM transcript expression in the human trophoblastic cell line HTR-8/SVneo. The results showed that the transcription levels of ALCAM were dramatically upregulated by 5-Aza-dC treatment in a concentration- and time-dependent manner, beginning at 12 h and peaking at ~48 h of 2.5 μM 5-Aza-dC treatment (Fig. 5a, b).

ALCAM mRNA expression is enhanced by 5-Aza-dC treatment in trophoblastic cells. a Concentration-dependent induction of ALCAM by 0, 1.25, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM 5-Aza-dC for 24 h. b Time-dependent (0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h) induction of ALCAM mRNA expression by 2.5 μM 5-Aza-dC. Results are the means ± SEM from three independent experiments performed in duplicate

Discussion

At present, there is no effective intervention or robust biomarker for PE; thus, PE is usually diagnosed at a later stage in gestation when the pregnant woman has developed severe symptoms and significant systemic injury [21]. Therefore, clarifying the molecular mechanisms responsible for the pathogenesis of PE and identifying molecular targets for diagnosis and therapy are urgent needs. Recent evidence has identified a wide range of PE-specific genes with aberrant DNA methylation and gene expression, indicating that epigenetic mechanisms contribute to PE. In the present study, we innovatively found that the mRNA and protein expression of ALCAM were dramatically reduced in PE placentas, in accordance with the increased methylation status of the ALCAM promoter in the PE placenta and peripheral blood. Moreover, the hypermethylation of the ALCAM promoter was significantly related to the clinical manifestation of PE, suggesting that the regulation of ALCAM by epigenetic mechanisms might be involved in PE pathogenesis.

It has been proven that the dysregulation of genes and proteins associated with cell adhesion, motility, and invasiveness has a significant effect on trophoblast function, contributing to PE [10, 12, 22,23,24]. The focus of ALCAM functional studies has been primarily on its roles in cell motility, invasiveness, and adhesion in various cancers, and ALCAM has been repeatedly demonstrated to be a marker of metastasis in many tumor cell types [4, 5, 25,26,27,28]. As an adhesion molecule, ALCAM is involved in blastocyst implantation and placental differentiation, facilitating maternal-fetal communication [29, 30]. However, few studies on the expression and role of ALCAM in placenta-related diseases have been performed. In the current study, based on the physiological functions of ALCAM, we speculate that alterations in ALCAM gene expression might play an important role in the disruption of trophoblast cell behavior. To clarify ALCAM expression, we measured the relative expression levels of ALCAM mRNA and protein in placental tissue, and the results showed that the mRNA and protein levels of ALCAM were decreased in PE placental tissue. Our results suggest that lower expression of the ALCAM gene may be associated with PE. Further cellular and animal experiments are needed to test the hypothesis that a decline in ALCAM expression may contribute to the onset of PE by disrupting trophoblast cell motility, invasiveness, and adhesion.

Moreover, our results show that there is abundant hypermethylation of ALCAM gene promoter regions in the placental tissues of PE patients, consistent with the findings by Yeung et al. based on methylation tests in a small number of samples [14]. Notably, our study further verified these changes in methylation in the peripheral blood and placental tissues of a larger number of samples. In addition, we further analyzed the relationship between methylation status and clinical features and found that gestational age, fetal weight, and BMI were significantly different between women with a hemimethylated promoter and those with an unmethylated promoter, which suggested that these factors may be major contributors to altered DNA methylation. Therefore, we adjusted our analysis and found that there was also differential methylation between PE cases and normal control subjects. Many studies have also confirmed that DNA methylation is related to gene expression and that hypermethylation of gene promoter regions may underlie this dysregulation of ALCAM expression [10, 11, 22, 23, 31, 32]. Therefore, we speculated that the lower expression of genes caused by hypermethylation leads to changes in cell behavior, which in turn trigger the occurrence of PE. Therefore, the hypermethylation of the ALCAM promoter CpG site in placental tissue can be considered a potential target of PE. However, substantial studies, such as those involving pyrosulfuric acid sequencing or bisulfite sequencing, are required in the future to better understand the mechanisms underlying the regulation of ALCAM promoter methylation in PE.

However, the limitation is that placental tissue is usually acquired after delivery, so we cannot confirm the diagnosis of PE by early detection of the methylation status in placental tissues. In 1997, Lo et al. confirmed the presence of fetal cell-free DNA in maternal blood for the first time, and thus, the use of fetal cell-free DNA in the maternal circulation to diagnose diseases, such as PE, has become a research hotspot for noninvasive prenatal diagnosis [33, 34]. Our results also confirmed that the degree of ALCAM promoter methylation in the peripheral blood was consistent with that in the placental tissue. Moreover, we found that there was a higher methylation rate in the ALCAM promoter regions of both the mild PE and severe PE groups than in that of the control group; however, there was no difference between the mild and severe PE groups, suggesting that ALCAM may be considered a potential predictive diagnostic marker of PE.

Conclusions

In summary, our study indicates that DNA methylation may play an important role in the regulation of ALCAM expression. Furthermore, alterations in ALCAM gene expression in PE patients indicate that methylation may contribute to functional changes in the placenta, such as inhibition of trophoblast cell migration and invasion. Thus, these findings suggest that ALCAM may be a potential marker and target for the clinical diagnosis and therapy of PE.

References

Mol B, Roberts C, Thangaratinam S, Magee L, de Groot C, Hofmeyr G. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2016;387:999–1011.

Nevalainen J, Skarp S, Savolainen E, Ryynänen M, Järvenpää J. Intrauterine growth restriction and placental gene expression in severe preeclampsia, comparing early-onset and late-onset forms. J Perinat Med. 2017;45:869–77.

Pennington KA, Schlitt JM, Jackson DL, Schulz LC, Schust DJ. Preeclampsia: multiple approaches for a multifactorial disease. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5:9–18.

Jannie KM, Stipp CS, Weiner JA. ALCAM regulates motility, invasiveness, and adherens junction formation in uveal melanoma cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39330.

Devis L, Moiola CP, Masia N, Martinez-Garcia E, Santacana M, Stirbat TV, et al. Activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM) is a marker of recurrence and promotes cell migration, invasion, and metastasis in early-stage endometrioid endometrial cancer. J Pathol. 2017;241:475–87.

Haouzi D, Dechaud H, Assou S, Monzo C, de Vos J, Hamamah S. Transcriptome analysis reveals dialogues between human trophectoderm and endometrial cells during the implantation period. Hum Reprod. (Oxford, England). 2011;26:1440–9.

Lian IA, Toft JH, Olsen GD, Langaas M, Bjorge L, Eide IP, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 1 in pre-eclampsia and fetal growth restriction: reduced gene expression in decidual tissue and protein expression in extravillous trophoblasts. Placenta. 2010;31:615–20.

Panagodage S, Yong HE, Da Silva Costa F, Borg AJ, Kalionis B, Brennecke SP, et al. Low-dose acetylsalicylic acid treatment modulates the production of cytokines and improves trophoblast function in an in vitro model of early-onset preeclampsia. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:3217–24.

Ge J, Wang J, Zhang F, Diao B, Song ZF, Shan LL, et al. Correlation between MTHFR gene methylation and pre-eclampsia, and its clinical significance. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:8021–8.

Chu T, Bunce K, Shaw P, Shridhar V, Althouse A, Hubel C, et al. Comprehensive analysis of preeclampsia-associated DNA methylation in the placenta. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e107318.

Anderson CM, Ralph JL, Wright ML, Linggi B, Ohm JE. DNA methylation as a biomarker for preeclampsia. Biol Res Nurs. 2014;16:409–20.

Anton L, Brown AG, Bartolomei MS, Elovitz MA. Differential methylation of genes associated with cell adhesion in preeclamptic placentas. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100148.

Xuan J, Jing Z, Yuanfang Z, Xiaoju H, Pei L, Guiyin J, et al. Comprehensive analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression of placental tissue in preeclampsia patients. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2016;35:129–38.

Yeung KR, Chiu CL, Pidsley R, Makris A, Hennessy A, Lind JM. DNA methylation profiles in preeclampsia and healthy control placentas. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2016;310:H1295–303.

Piletič K, Kunej T. MicroRNA epigenetic signatures in human disease. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90:2405–19.

Robinson WP, Price EM. The human placental methylome. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a023044.

Ching T, Song MA, Tiirikainen M, Molnar J, Berry M, Towner D, et al. Genome-wide hypermethylation coupled with promoter hypomethylation in the chorioamniotic membranes of early onset pre-eclampsia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:885–904.

Rahat B, Najar R, Hamid A, Bagga R, Kaur J. The role of aberrant methylation of trophoblastic stem cell origin in the pathogenesis and diagnosis of placental disorders. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37:133–43.

Novakovic B, Evain-Brion D, Murthi P, Fournier T, Saffery R. Variable DAXX gene methylation is a common feature of placental trophoblast differentiation, preeclampsia, and response to hypoxia. FASEB J. 2017;31:2380–92.

Lowe SA, Bowyer L, Lust K, McMahon LP, Morton M, North RA, et al. SOMANZ guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;55:e1–29.

Grotegut C. Prevention of preeclampsia. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:4396–8.

Jia Y, Li T, Huang X, Xu X, Zhou X, Jia L, et al. Dysregulated DNA methyltransferase 3A upregulates IGFBP5 to suppress trophoblast cell migration and invasion in preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2017;69:356–66.

Martin E, Ray P, Smeester L, Grace M, Boggess K, Fry R. Epigenetics and preeclampsia: defining functional epimutations in the preeclamptic placenta related to the TGF-β pathway. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0141294.

Brew O, Sullivan MH, Woodman A. Comparison of normal and pre-eclamptic placental gene expression: a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0161504.

Fujiwara K, Ohuchida K, Sada M, Horioka K, Ulrich CD 3rd, Shindo K, et al. CD166/ALCAM expression is characteristic of tumorigenicity and invasive and migratory activities of pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e107247.

Jeong YJ, Oh HK, Park SH, Bong JG. Prognostic significance of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM) in association with promoter methylation of the ALCAM gene in breast cancer. Molecules. 2018;23:131.

Lu XY, Chen D, Gu XY, Ding J, Zhao YJ, Zhao Q, et al. Predicting value of ALCAM as a target gene of microRNA-483-5p in patients with early recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Pharm. 2017;8:973.

Smith NR, Davies PS, Levin TG, Gallagher AC, Keene DR, Sengupta SK, et al. Cell adhesion molecule CD166/ALCAM functions within the crypt to orchestrate murine intestinal stem cell homeostasis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:389–409.

Fujiwara H, Tatsumi K, Kosaka K, Sato Y, Higuchi T, Yoshioka S, et al. Human blastocysts and endometrial epithelial cells express activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM/CD166). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3437–43.

Abumaree MH, Al Jumah MA, Kalionis B, Jawdat D, Al Khaldi A, AlTalabani AA, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from chorionic villi of human term placenta. Stem cell reviews. 2013;9:16–31.

Rezaei M, Eskandari F, Mohammadpour-Gharehbagh A, Harati-Sadegh M, Teimoori B, Salimi S. Hypomethylation of the miRNA-34a gene promoter is associated with Severe Preeclampsia. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2018;41:1–5.

Blair JD, Yuen RK, Lim BK, McFadden DE, von Dadelszen P, Robinson WP. Widespread DNA hypomethylation at gene enhancer regions in placentas associated with early-onset pre-eclampsia. Molecular human reproduction. 2013;19:697–708.

Orhant L, Rondeau S, Vasson A, Anselem O, Goffinet F, Allach El Khattabi L, et al. Droplet digital PCR, a new approach to analyze fetal DNA from maternal blood: application to the determination of fetal RHD genotype. Ann Biol Clin. 2016;74:269–77.

Shea J, Diamandis E, Hoffman B, Lo Y, Canick J, van den Boom D. A new era in prenatal diagnosis: the use of cell-free fetal DNA in maternal circulation for detection of chromosomal aneuploidies. Clin Chem. 2013;59:1151–9.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the National Science Foundation of the P.R. China (No. 81600211); the Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2016HM28 and ZR2014HP017); and by the Application and Basic Research Project of Qingdao (18-2-2-27-jch).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, LZ and SL; Data curation, LZ and SL; Formal analysis, JL; Funding acquisition, LZ and SL; Investigation, ZY and WS; Methodology, QT and LZ; Project administration, LZ and SL; Resources, SL; Software, LW and YP; Supervision, ZY, WS, YG, QT and JL; Validation, LW, YP and YG; Writing—original draft, LW and YP; Writing—review and editing, LZ and SL.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Ll., Pan, Ys., Tang, Q. et al. Decreased ALCAM expression and promoter hypermethylation is associated with preeclampsia. Hypertens Res 43, 13–22 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0337-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0337-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Epigenetic landscape of placental tissue in preeclampsia: a systematic review of DNA methylation profiles

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2025)

-

Genes with abnormal DNA methylation in chorionic villi of spontaneous abortions with monosomy X

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2025)

-

DNA methylation landscape in pregnancy-induced hypertension: progress and challenges

Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (2024)